European Patent Convention

Topic: Finance

From HandWiki - Reading time: 20 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 20 min

Long name:

| |

|---|---|

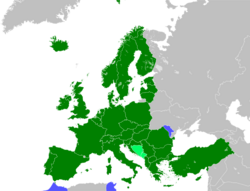

European Patent Convention Contracting States in dark green, extension agreement states in light green and validation agreement states in violet | |

| Signed | Script error: No such module "Date time". |

| Location | Munich, Germany |

| Effective | 7 October 1977 |

| Condition | six States on whose territory the total number of patent applications filed in 1970 amounted to at least 180 000 |

| Signatories | 16 |

| Parties | 39 |

| Depositary | Government of the Federal Republic of Germany |

| Languages | English, French and German |

The European Patent Convention (EPC), also known as the Convention on the Grant of European Patents of 5 October 1973, is a multilateral treaty instituting the European Patent Organisation and providing an autonomous legal system according to which European patents are granted. The term European patent is used to refer to patents granted under the European Patent Convention. However, a European patent is not a unitary right, but a group of essentially independent nationally enforceable, nationally revocable patents,[notes 1] subject to central revocation or narrowing as a group pursuant to two types of unified, post-grant procedures: a time-limited opposition procedure, which can be initiated by any person except the patent proprietor, and limitation and revocation procedures, which can be initiated by the patent proprietor only.

The EPC provides a legal framework for the granting of European patents,[1] via a single, harmonised procedure before the European Patent Office (EPO). A single patent application, in one language,[2] may be filed at the EPO in Munich,[3] at its branch in The Hague,[3][notes 2] at its sub-office in Berlin,[5] or at a national patent office of a Contracting State, if the national law of the State so permits.[6]

History

In September 1949, French Senator Henri Longchambon proposed to the Council of Europe the creation of a European Patent Office. His proposal, known as the "Longchambon plan", marked the beginning of the work on a European patent law aimed at a "European patent".[7] His plan was however not found to be practicable by the Council's Committee of Experts in patent matters. The meetings of the Committee nevertheless led to two Conventions, one on the formalities required for patent applications (1953) and one on the international classification of patent (1954).[8] The Council's Committee then carried on its work on substantive patent law, resulting in the signature of the Strasbourg Patent Convention in 1963.[8]

In 1973, the Munich Diplomatic Conference for the setting up of a European System for the Grant of Patents took place and the Convention was then signed in Munich (the Convention is sometimes known as the "Munich Convention"). The signature of the Convention was the accomplishment of a decade-long discussion during which Kurt Haertel, considered by many as the father of the European Patent Organisation, and François Savignon played a decisive role.

The Convention was officially signed by 16 countries on 5 October 1973.[9]

The Convention entered into force on 7 October 1977 for the following first countries: Belgium, Germany (then West Germany), France, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Switzerland and the United Kingdom, and on 1 May 1978 for Sweden. However, the first patent applications were filed on 1 June 1978 (date fixed by the Administrative Council which held its first meeting on 19 October 1977). Subsequently, other countries have joined the EPC.

The EPC is separate from the European Union (EU), and its membership is different; Switzerland , Liechtenstein, Turkey, Monaco, Iceland, Norway , North Macedonia, San Marino, Albania, Serbia, the United Kingdom , and Montenegro are party to the EPC but are not members of the EU. Further, the EU is not a party to the EPC, although all members of the EU are party to the EPC.[10] The Convention is, as of October 2022, in force in 39 countries.[11] Montenegro became the 39th Contracting State on 1 October 2022.[12][13]

A diplomatic conference was held in November 2000 in Munich to revise the Convention, amongst other things to integrate in the EPC new developments in international law and to add a level of judicial review of the Boards of Appeal decisions. The revised text, informally called the EPC 2000, entered into force on 13 December 2007.[14]

Cooperation agreements with non-contracting states: extension and validation agreements

| Contracting states and extension or validation states, in detail (with dates of entry into force). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Throughout the history of the EPC, some non-contracting States have concluded cooperation agreements with the European Patent Organisation, known as extension or validation agreements. These states then became "extension states" or "validation states", which means that European patents granted by the EPO may be extended to those countries through the payment of additional fees and completion of certain formalities. Such cooperation agreements are concluded by the President of the European Patent Office on behalf of the European Patent Organisation pursuant to Article 33(4) EPC, are not based on a "direct application of the EPC but solely on national law modelled on the EPC",[24] and exist to assist with the establishment of national property rights in these states.[25] As is the case in EPO contracting states, the rights conferred to European patents validated/extended to these states are the same as national patents in those states. However, the extension of a European patent or patent application to these states is "not subject to the jurisdiction of the [EPO] boards of appeal."[26]

As of October 2022, Bosnia and Herzegovina has an extension agreement with the EPO so that, in effect, this state can be designated in a European patent application. Several other "extension states" have since become states parties to the EPC. Furthermore, so-called "validation agreements" with Morocco, Moldova, Tunisia, and Cambodia are also in effect since 1 March 2015, 1 November 2015, 1 December 2017, and 1 March 2018, respectively.[18][27][19][20][28][21] A further validation agreement was signed with Georgia on 31 October 2019 and entered into force on 15 January 2024.[29][22]

Legal nature and content

The European Patent Convention is "a special agreement within the meaning of Article 19 of the Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property, signed in Paris on 20 March 1883 and last revised on 14 July 1967, and a regional patent treaty within the meaning of Article 45, paragraph 1, of the Patent Cooperation Treaty of 19 June 1970."[30] The European Patent Convention currently does not lead to the grant of centrally enforceable patents in all 39 countries, although the European Union patent would allow for unitary effect: centrally enforceability throughout 24 of the 27 countries of the European Union.

The content of the Convention includes several texts in addition to the main 178 articles.[31] These additional texts, which are integral parts of the Convention,[32] are:

- the "Implementing Regulations to the Convention on the Grant of European patents", commonly known as the "Implementing Regulations". The function of the Implementing Regulations is "to determine in more detail how the Articles should be applied".[33] In case of conflict between the provisions of the EPC and those of the Implementing Regulations, the provisions of the EPC prevail.[34]

- the "Protocol on Jurisdiction and the recognition of decisions in respect of the right to the grant of a European patent", commonly known as the "Protocol on Recognition". This protocol deals with the right to the grant of a European patent but exclusively applies to European patent applications.

- the "Protocol on Privileges and Immunities of the European Patent Organisation", commonly known as the "Protocol on Privileges and Immunities";

- the "Protocol on the Centralisation of the European Patent System and on its Introduction", commonly known as the "Protocol on Centralisation";

- the "Protocol on the Interpretation of Article 69 of the Convention";

- the "Protocol on the Staff Complement of the European Patent Office at The Hague", commonly known as the "Protocol on Staff Complement".

Substantive patent law

One of the most important articles of the Convention, Article 52(1) EPC, entitled "Patentable inventions", states:

European patents shall be granted for any inventions, in all fields of technology, providing that they are new, involve an inventive step, and are susceptible of industrial application.[35]

This article constitutes the "fundamental provision of the EPC which governs the patentability of inventions".[36]

However, the EPC provides further indications on what is patentable. There are exclusions under Article 52(2) and (3) EPC and exclusions under Article 53 EPC.

First, discoveries, scientific theories, mathematical methods,[37] aesthetic creations,[38] schemes, rules and methods for performing mental acts, playing games or doing business, programs for computers[39] and presentations of information[40] are not regarded as inventions[41] and are excluded from patentability only to the extent that the invention relates to those areas as such.[42] This is "a negative, non-exhaustive list of what should not be regarded as an invention within the meaning of Article 52(1) EPC."[36] (For further information, see also: Software patents under the EPC).

The second set of exclusions, or exceptions, include:

- Inventions contrary to "ordre public" or morality,[43]

- Plant or animal varieties and essentially biological processes for the production of plants and animals,[44] and

- Methods for treatment of the human or animal body by surgery or therapy, and diagnostic methods practised on the human or animal body,[45] which have been excluded for "socio-ethical considerations and considerations of public health".[46] Products, "in particular substances or compositions", for use in any of these therapeutic or diagnostic methods are not excluded from patentability, however.[45]

Unified prosecution phase

The Convention also includes provisions setting out filing requirements of European applications, the procedure up to grant, the opposition procedure and other aspects relating to the prosecution of patent applications under the Convention.

European patent applications may be filed in any language, but they are prosecuted only in one of the three official languages of the EPO – English, French and German. If an application is filed in another language than an official language, a translation must be filed into one of the three official languages,[47] within two months from the date of filing.[48] The official language of filing (or of the translation) is adopted as the "language of proceedings" and is used by the EPO for communications.

European patent applications are prosecuted in a similar fashion to most patent systems – the invention is searched and published, and subsequently examined for compliance with the requirements of the EPC.

During the prosecution phase, a European patent is a single regional proceeding, and "the grant of a European patent may be requested for one or more of the Contracting States."[49] All Contracting States are considered designated upon filing of a European patent application.[50] and the designations need to be "confirmed" later during the procedure through the payment of designation fees.[51] Once granted by the EPO,[52] a European patent comes into existence effectively as a group of national patents in each of the designated Contracting States.

Opposition

There are only two types of centrally executed procedures after grant, the opposition procedure and the limitation and revocation procedures. The opposition procedure, governed by the EPC, allows third parties to file an opposition against a European patent within 9 months of the date of grant of that patent.[53] It is a quasi-judicial process, subject to appeal, which can lead to maintenance, maintenance in amended form or revocation of a European patent. Simultaneously to the opposition, a European patent may be the subject of litigation at a national level (for example an infringement dispute). National courts may suspend such infringement proceedings pending outcome of the opposition proceedings to avoid proceedings running in parallel and the uncertainties that may arise from that.

Grant, effect and need for translations

In contrast to the unified, regional character of a European patent application, the granted European patent does not comprise, in effect, any such unitary character, except for the opposition procedure.[notes 7] In other words, one European patent in one Contracting State[notes 8] is effectively independent of the same European patent in each other Contracting State, except for the opposition procedure.

A European patent confers rights on its proprietor, in each Contracting State in respect of which it is granted, from the date of publication of the mention of its grant in the European Patent Bulletin.[54] That is also the date of publication of the B1 document, i.e. the European patent specification.[55] This means that the European patent is granted and confers rights in all its designated Contracting States at the date of mention of the grant, whether or not a prescribed translation is filed with a national patent office later on (though the right may later be deemed never to have existed in any particular State if a translation is not subsequently filed in time, as described below).

A translation of a granted European patent must be filed in some EPC Contracting States to avoid loss of right. Namely, in the Contracting States which have "prescribe[d] that if the text, in which the European Patent Office intends to grant a European patent (...) is not drawn up in one of its official languages, the applicant for or proprietor of the patent shall supply to its central industrial property office a translation of this text in one of its official languages at his option or, where that State has prescribed the use of one specific official language, in that language".[56] The European patent is void ab initio in a designated Contracting State where the required translation (if required) is not filed within the prescribed time limit after grant.[57] In other Contracting States, no translation needs to be filed, for example in Ireland if the European patent is in English. In those Contracting States where the London Agreement is in force the requirement to file a translation of the European patent has been entirely or partially waived.[58] If a translation is required, a fee covering the publication of said translation may be due as well.[59]

Enforcement and validity

Almost all attributes of a European patent in a Contracting State, i.e. ownership, validity, and infringement, are determined independently under respective national law, except for the opposition procedure, limitation procedure, and revocation procedure as discussed above. Though the EPC imposes some common limits, the EPC expressly adopts national law for interpretation of all substantive attributes of a European patent in a Contracting State, with a few exceptions.[60]

Infringement

Infringement is remitted entirely to national law and to national courts.[61] In one of its very few substantive interventions into national law, the EPC requires that national courts must consider the "direct product of a patented process" to be an infringement.[62] The "extent of the protection" conferred by a European patent is determined primarily by reference to the claims of the European patent (rather than by the disclosure of the specification and drawings, as in some older patent systems), though the description and drawings are to be used as interpretive aids in determining the meaning of the claims.[63] A "Protocol on the Interpretation of Article 69 EPC" provides further guidance, that claims are to be construed using a "fair" middle position, neither "strict, literal" nor as mere guidelines to considering the description and drawings, though of course even the protocol is subject to national interpretation.[64] The authentic text of a European patent application and of a European patent are the documents in the language of the proceedings.[65][66]

All other substantive rights attached to a European patent in a Contracting State, such as what acts constitute infringement (indirect and divided infringement, infringement by equivalents, extraterritorial infringement, infringement outside the term of the patent with economic effect during the term of the patent, infringement of product claims by processes for making or using, exports, assembly of parts into an infringing whole, etc.), the effect of prosecution history on interpretation of the claims, remedies for infringement or bad faith enforcement (injunction, damages, attorney fees, other civil penalties for wilful infringement, etc.), equitable defences, coexistence of an EP national daughter and a national patent for identical subject matter, ownership and assignment, extensions to patent term for regulatory approval, etc., are expressly remitted to national law.[67]

For a period in the late-1990s, national courts issued cross-border injunctions covering all EP jurisdictions, but this has been limited by the European Court of Justice. In two cases in July 2006 interpreting Articles 6.1 and 16.4 of the Brussels Convention, the European Court of Justice held that European patents are national rights that must be enforced nationally, that it was "unavoidable" that infringements of the same European patent have to be litigated in each relevant national court, even if the lawsuit is against the same group of companies, and that cross-border injunctions are not available.[68]

Validity

Validity is also remitted largely to national law and national courts. Article 138(1) EPC limits the application of national law to only the following grounds of invalidity, and specifies that the standards for each ground are those of national law:

- if the subject-matter of the European patent is not patentable within the terms of Articles 52 to 57 EPC (see "Substantive patent law" section above);

- if the disclosure does not permit the invention to be carried out by a person skilled in the art;[69]

- if amendments have been made such that the subject-matter extends beyond the content of the application as filed;[70]

- if the claims have been broadened post-grant, e.g. in opposition proceedings;[71]

- an improper proprietor[72]—in some jurisdictions, only the person pretending to be entitled to the European patent can raise this specific ground, so that the resulting nullity of the patent may be relative to some persons only[73]—.

Term (duration) of a European patent

The EPC requires all jurisdictions to give a European patent a term of 20 years from the filing date,[74] the filing date being the actual date of filing an application for a European patent or the date of filing of an international application under the PCT designating the EPO. The filing date is not necessarily the priority date, which can be up to one year earlier.[notes 9] The term of a granted European patent may be extended under national law if national law provides term extension to compensate for pre-marketing regulatory approval.[75] For EEA member states this is by means of a supplementary protection certificate (SPC).

Relation with the Patent Cooperation Treaty

A European patent application may result from the filing of an international application under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), i.e. the filing of a PCT application, and then the entry into "European regional phase",[76] i.e. the transition from the international to the European procedural stages. The European patent application is therefore said to be a "Euro-PCT application" and the EPO is said to act as a designated or elected Office.[77] In case of conflict between the provisions of the EPC and those of the PCT, the provisions of the PCT and its Regulations prevail over those of the EPC.[78]

Twelve EPC Contracting States, namely Belgium, Cyprus, France, Greece, Ireland, Latvia,[79] Malta,[80] Monaco, Montenegro,[81] the Netherlands, San Marino,[82] and Slovenia, have "closed their national route".[83] This means that, for these countries, it is not possible to obtain a national patent through the international (PCT) phase without entering into the regional European phase and obtaining a European patent. The "national route" for Italy was closed until 30 June 2020, but Italy then reopened it for PCT applications filed on or after 1 July 2020.[84]

See also

- Glossary of patent law terms

- Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (1969)

Notes

- ↑ The view that a European patent issues as independent national patents in each designated Contracting state is very convenient from a practical point of view. Some however consider this view as incorrect:

- "The view that, after grant, a European patent breaks up into a bundle of national patents in designated Contracting States may appear plausible, but it is incorrect both in law and systematically", Singer/Stauder, The European Patent Convention, A Commentary, Munich, 2003, under Article 2.

- "(...) a European patent is no more than a bundle of national patents pursuant to a single application. Until a true community patent becomes a reality it seems likely that true community enforcement will continue to elude patent owners." Tom Scourfield, Jurisdiction and Patents: ECJ rules on forum for validity and cross-border patent enforcement, The CIPA Journal, August 2006, Volume 35 No. 8, p. 535.

- ↑ The Hague branch of the EPO is actually located in Rijswijk.[4]

- ↑ The European Patent Convention (EPC) applies also to French overseas territories. See Synopsis of the territorial field of application of international patent treaties (situation on 1 March 2013), EPO OJ 4/2013, p. 269, footnote 4.

- ↑ The European Patent Convention was ratified on 7 October 1977 for the European Netherlands. From 4 April 2007, the EPC applied also to the Netherlands Antilles (presently Caribbean Netherlands, Curaçao and Sint Maarten). The Convention does not apply to Aruba. See Synopsis of the territorial field of application of international patent treaties (situation on 1 March 2013), EPO OJ 4/2013, p. 269, footnote 6, and Guidelines for Examination in the EPO, section foreword_6 "Contracting States to the EPC".

- ↑ The European Patent Convention also applies to the Isle of Man. See Synopsis of the territorial field of application of international patent treaties (situation on 1 March 2013), EPO OJ 4/2013, p. 269, footnote 7. Furthermore, European patents in force in the UK can also be registered in the Crown dependencies and overseas territories Anguilla, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Falkland Islands, Gibraltar, Guernsey, Jersey, Montserrat and Turks and Caicos Islands, as well as the British Commonwealth countries Belize, Fiji, Grenada, Guyana, Kiribati, Solomon Islands and Tuvalu, generally within 3 years of grant of the European patent as explained in "Registration of European patents (UK) in crown dependencies, UK overseas territories and Commonwealth countries", OJ EPO 2018, A97. Finally, regarding registration of European patent applications and patents in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR) is also possible, see "Patent protection in Hong Kong Special Administration Region", OJ EPO 2009, 546 and patent law in Hong Kong.

- ↑ The European Patent Convention does not apply however to Greenland and the Faroe Islands. See Synopsis of the territorial field of application of international patent treaties (situation on 1 March 2013), EPO OJ 4/2013, p. 269, footnote 3.

- ↑ In addition to the opposition procedure and even after it has ended, particular acts can still be performed before the European Patent Office, such as requesting a rectification of an incorrect designation of inventor under Rule 19(1) EPC. [needs update] "Rectification may [indeed] be requested after the proceedings before the EPO are terminated" (Guid. A III 5.6).

- ↑ There is no consistent usage of a particular expression to refer to "the European patent in a particular designated Contracting State for which it is granted". The article uses the expression "a European patent in a Contracting State" which is considered to be the most consistent with the authoritative text, i.e. the EPC.

- ↑ In rare cases, the filing date can be even more than one year after the priority date if the applicant missed the priority year and successfully obtained a re-establishment of rights in respect of the priority period. See Guidelines for Examination in the EPO, section f-vi, 3.6 .

References

- ↑ Article 2(1) EPC

- ↑ Article 14 EPC

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Article 75(1)(a) EPC

- ↑ Enlarged Board of Appeal decision G 7/88 (Administrative Agreement) of 16.11.1990, Summary of Facts and Submissions, V.(3)

- ↑ Decision of the President of the European Patent Office dated 10 May 1989 on the setting up of a Filing Office in the Berlin sub-office of the European Patent Office, OJ 1989, 218

- ↑ Article 75(1)(b) EPC

- ↑ Bossung, Otto. "The Return of European Patent Law in the European Union". IIC 27 (3/1996). http://www.suepo.org/public/background/bossung_en.htm. Retrieved 30 June 2012. "Work on a European patent law aimed at a "European patent" had begun in Strasbourg in 1949 with the Longchambon plan.".

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 G. W. Tookey, Patents in the European Field in Council of Europe, Council of Europe staff, European Yearbook 1969, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1971, pages 76–97, ISBN 90-247-1218-1.

- ↑ "European Patent Office". Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/European-Patent-Office.

- ↑ "ECJ Case C-1/09, Opinion, point 3". https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:62009CV0001. "The European Patent Convention (‘the EPC’), signed at Munich on 5 October 1973, is a treaty to which 38 States, including all the Member States of the European Union, are now parties. The European Union is not a party to the EPC. (...)"

- ↑ "Member states of the European Patent Organisation". European Patent Office. https://www.epo.org/about-us/foundation/member-states.html.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Montenegro on its way to become 39th EPC Contracting State on 1 October 2022" (in en). European Patent Office. 27 July 2022. https://www.epo.org/news-events/news/2022/20220727.html.

- ↑ "Montenegro becomes 39th Contracting State" (in en). European Patent Office. 1 October 2022. https://www.epo.org/news-events/news/2022/20221001.html.

- ↑ Official Journal of the EPO, 2/2006, Notice from the European Patent Office dated 27 January 2006 concerning deposit of the fifteenth instrument of ratification of the EPC Revision Act

- ↑ EPO web site, San Marino accedes to the European Patent Convention , Updates, 8 May 2009. Consulted on 8 May 2009. See also EPO, San Marino accedes to the European Patent Convention, EPO Official Journal 6/2009, p. 396.

- ↑ Albania accedes to the European Patent Convention , Updates, 1 March 2010. Consulted on 2 May 2010.

- ↑ Serbia accedes to the European Patent Convention , 30 July 2010. Consulted on 31 July 2010.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Morocco recognises European patents as national patents". European Patent Office. 19 January 2015. http://www.epo.org/news-issues/news/2015/20150119.html.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "European patents to cover Moldova". European Patent Office. 8 October 2015. https://www.epo.org/news-issues/news/2015/20151008.html.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Brevets européens en Tunisie : L'accord de validation entre l'OEB et la Tunisie entrera en vigueur le 1er décembre" (in fr). European Patent Office. 3 October 2017. http://www.epo.org/news-issues/news/2017/20171004.html.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Validation of European patents in Cambodia (KH) with effect from 1 March 2018". European Patent Office. 9 February 2018. https://www.epo.org/law-practice/legal-texts/official-journal/information-epo/archive/20180209.html.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "OJ EPO 2023, A105 – Validation of European patents in Georgia (GE) with effect from 15 January 2024". https://www.epo.org/en/legal/official-journal/2023/12/a105.html.

- ↑ Guidelines for Examination in the EPO, section a-iii, 12.1 : "Extension and validation of European patent applications and patents to/in states not party to the EPC" > "General remarks".

- ↑ "National Law relating to EPC". EPO. http://www.epo.org/law-practice/legal-texts/html/natlaw/en/a/index.htm. "The extension system largely corresponds to the EPC system operating in the EPC contracting states, except that it is based not on direct application of the EPC but solely on national law modelled on the EPC. It is therefore subject to the national extension rules of the country concerned."

- ↑ Template:EPO Case law book 2019: "Extension agreements and ordinances", "Legal nature"

- ↑ Template:EPO Case law book 2019: "No jurisdiction of the boards of appeal"

- ↑ "Validation agreement with Morocco enters into force". EPO. 1 March 2015. http://www.epo.org/news-issues/news/2015/20150302.html.

- ↑ "Validation states". European Patent Office. http://www.epo.org/about-us/foundation/validation-states.html.

- ↑ "Simplifying access to patent protection in Georgia". European Patent Office. 5 November 2019. https://www.epo.org/news-issues/news/2019/20191105b.html.

- ↑ "Preamble [of the European Patent Convention"]. EPO. http://www.epo.org/law-practice/legal-texts/html/epc/2013/e/apre.html. See also Enlarged Board of Appeal opinion G2/98, "Reasons for the Opinion", point 3, first sentence: "The EPC constitutes, according to its preamble, a special agreement within the meaning of Article 19 of the Paris Convention".

- ↑ "The European Patent Convention". EPO. http://www.epo.org/law-practice/legal-texts/html/epc/2013/e/ma1.html.

- ↑ Article 164(1) EPC

- ↑ Template:EPO Case law book 2019: "Implementing Regulations"

- ↑ Article 164(2) EPC

- ↑ See Article 52(1) EPC. The state of the art is further defined in Articles 54(2)-(5), and a limited grace period is specified in Article 55 EPC, but this is only relevant in cases of breach of confidence or disclosure of the invention in a recognised international exhibition.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Decision T 154/04 of 15 November 2006, Reasons 6.

- ↑ Article 52(2)(a) EPC

- ↑ Article 52(2)(b) EPC

- ↑ Article 52(2)(c) EPC

- ↑ Article 52(2)(d) EPC

- ↑ Article 52(2) EPC

- ↑ Article 52(3) EPC

- ↑ Article 53(a) EPC

- ↑ Article 53(b) EPC

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Article 53(c) EPC

- ↑ Decision G 1/07 of 15 February 2010, Reasons 3.3.6. See also G 1/07.

- ↑ Article 14(2) EPC; Guidelines for Examination in the EPO, section a-vii, 1.1 : "Admissible languages; time limit for filing the translation of the application"; "European patent applications can be filed in any language."

- ↑ Rule 6(1) EPC

- ↑ Article 3 EPC

- ↑ Article 79 EPC

- ↑ Article 79(2) EPC

- ↑ Article 4 EPC

- ↑ Article 99 EPC

- ↑ Article 64(1) EPC: EP patent has same effect as national patent in "each Contracting State in respect of which it is granted"; Article 97(2) and (4) EPC: decision to grant "for the designated Contracting States" is made by the examining division.

- ↑ Article 98 EPC

- ↑ Article 65(1) EPC

- ↑ Article 65(3) EPC

- ↑ Veronese & Watchorn 2008, Chapter XI.4

- ↑ Article 65(2) EPC; National law, Chapter IV, Filing of translations of the patent specification under Article 65 EPC (regarding implementation in EPC Contracting States)

- ↑ e.g. Article 2(2) EPC, Article 64(1) and(3) EPC, Article 66 EPC, Article 74 EPC

- ↑ Article 64(3) EPC

- ↑ Article 64(2) EPC

- ↑ Article 69(1) EPC

- ↑ E.g., Southco Inc v Dzus, [1992] R.P.C. 299 CA; Improver Corp. v Remington Products Inc [1990] FSR 181.

- ↑ Article 70 EPC

- ↑ Singer & Stauder 2003a, under Article 2, section "EPC provisions on European patents that take precedence over national law"

- ↑ Article 2(2) EPC

- ↑ Case C-4/03, Gesellschaft für Antriebstechnik v Lamellen und Kupplungsbau Beteiligungs KG, (European Ct. of Justice 13 July 2006) ; Case C-539/03, Roche Nederland BV v Primus, (European Ct. of Justice 13 July 2006)

- ↑ Article 138(1)(b) EPC

- ↑ Article 138(1)(c) EPC, Article 123(2) EPC

- ↑ Article 138(1)(d) EPC, Article 123(3) EPC

- ↑ Article 138(1)(e) EPC, Article 60 EPC

- ↑ (in French) Laurent Teyssedre, La nullité tirée du motif de l'Art 138(1) e) est relative, Le blog du droit européen des brevets, 5 March 2012. Consulted on 10 March 2012.

- ↑ Article 63(1) EPC

- ↑ Article 63(2)(b) EPC

- ↑ See Article 11(3) PCT, which provides a legal fiction according to which an international application, i.e. a PCT application, has the effect of a regular European patent application as of the international filing date under certain conditions (see for instance Decision J 18/09 of the Legal Board of Appeal 3.1.01 of 1 September 2010, Reasons 7 and 8); and Article 150(2), (first sentence) EPC: "International applications filed under the PCT may be the subject of proceedings before the European Patent Office."

- ↑ Guidelines for Examination in the EPO, section e-ix, 2 : "EPO as designated or elected Office".

- ↑ Article 150(2), (third sentence) EPC

- ↑ Latvia: Closing of the National Route via the PCT, PCT Newsletter of April 2007.

- ↑ "European Patent Office web site, Accession to the PCT by Malta (MT) , Information from the European Patent Office, 2 January 2007.

- ↑ "The Ministry of Economic Development and Tourism (Montenegro): Ceasing of Receiving Office Functions and Closure of National Route" (in en). PCT Newsletter (10/2022). October 2022. https://www.wipo.int/pct/en/newslett/2022/article_0004.html. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ↑ "The Patent and Trademark Office (San Marino): Ceasing of Receiving Office Functions and Closure of National Route". PCT Newsletter 2019 (12). December 2019. https://www.wipo.int/pct/en/newslett/2019/article_0002.html. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ↑ "The Ministry of Economic Development and Tourism (Montenegro): Ceasing of Receiving Office Functions and Closure of National Route" (in en). PCT Newsletter (10/2022). October 2022. https://www.wipo.int/pct/en/newslett/2022/article_0004.html. Retrieved 25 October 2022. "The list of States which are party to the EPC and which have closed the national route now includes Belgium, Cyprus, France, Greece, Ireland, Latvia, Malta, Monaco, Montenegro, the Netherlands, San Marino and Slovenia.".

- ↑ "Italian Patent and Trademark Office: Opening of National Route". PCT Newsletter (5/2020): 3. May 2020. https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pctndocs/en/2020/pct_news_2020_5.pdf. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

Further reading

- M. van Empel (14 November 1975). The Granting of European Patents. Springer Netherlands. ISBN 978-90-286-0365-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=zbIwAQAAIAAJ.

- Gerald Paterson (1992). The European Patent System: The Law and Practice of the European Patent Convention. Sweet and Maxwell. https://books.google.com/books?id=EpnQxQEACAAJ.

- Singer, Margarete; Stauder, Dieter (2003a). The European Patent Convention: A Commentary. Substantive Patent Law – Preamble, Articles 1 to 89. Thomson/Sweet & Maxwell. ISBN 978-0-421-83150-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=r8ttmQEACAAJ.

- Singer, Margarete; Stauder, Dieter (2003b). The European Patent Convention: A Commentary. Procedural patent law - article 90 to article 178. Volume 2. Sweet & Maxwell. ISBN 978-0-421-83170-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=30aPswEACAAJ.

- Veronese, Andrea; Watchorn, Peter (2008). Procedural Law Under the EPC-2000: A Practical Guide for Patent Professionals and Candidates for the European Qualifying Examination. Kastner. ISBN 978-3-937082-90-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=OqSaYgEACAAJ.

- Marcus O. Müller; Cees A.M. Mulder (27 February 2015). Proceedings Before the European Patent Office: A Practical Guide to Success in Opposition and Appeal. Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78471-010-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=WgGMBgAAQBAJ.

- Benkard (2022). Beckedorf, Ingo; Ehlers, Jochen. eds (in de). Europäisches Patentübereinkommen (4. Auflage ed.). München: C.H.BECK.. ISBN 978-3-406-76195-9.

- Visser's Annotated European Patent Convention (2022 ed.). Alphen aan den Rijn: Kluwer Law International. 2022. ISBN 9789403545011.

External links

- The European Patent Convention

- Legal texts from the European Patent Office (EPO), including the text of the European Patent Convention.

|

KSF

KSF