Methuen Treaty

Topic: Finance

From HandWiki - Reading time: 6 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 6 min

The Methuen Treaty was a military and commercial treaty between England and Portugal that was signed in 1703 as part of the War of the Spanish Succession.

The treaty stipulated that no tax higher than the tax charged for an equal amount of French wines could be charged for Portuguese wines (but see below) exported to England, and that English textiles would be admitted to Portugal at all times, regardless of the geopolitical situation in each of the two nations (to ensure England would still accept Portuguese wine in periods when not at war with France).[1][2]

The Methuen Treaty has been the subject of diverse interpretations.[3] Detractors, including Luís da Cunha, argued that the influx of English woollens led to the decline of the Portuguese wool industry.[4][5] Additionally, emphasis on wine production, while bringing prosperity to certain regions, left Portugal heavily reliant on England as its primary wine buyer.[6] Critics contended that the focus on wine came at the expense of other agricultural sectors[7] and redirected the nation away from its path towards industrialization.[8][9][10]

In defense of the treaty, it's been asserted that Portugal lacked the necessary resources for substantial manufacturing endeavors,[11][3] and its industries were already grappling with stagnation.[7] Furthermore, some believed that the treaty did not confine Portugal's trade;[3] instead, it played a pivotal role in augmenting the overall prosperity of the nation through increased commerce[1] and stronger ties with England.[11][12][13]

Background

At the start of the War of Spanish Succession Portugal was allied with France.[14][15] As part of this treaty, the French had guaranteed the Portuguese naval protection.[16] In 1702, the English navy sailed close to Lisbon on the way to and from Cadiz, proving to the Portuguese that the French could not keep their promise. They soon began negotiations with the Grand Alliance about switching sides.[17]

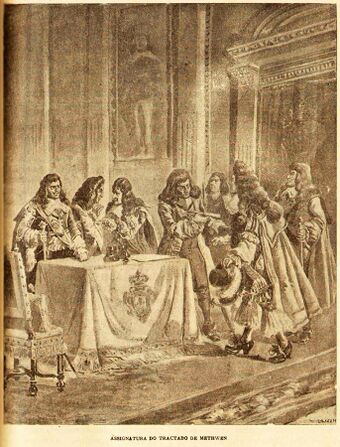

There were actually two Methuen Treaties. Both were negotiated for England in Lisbon by John Methuen[17] (c. 1650–1706), who served as a member of Parliament, Lord Chancellor of Ireland,[18] Privy Counsellor, envoy and then ambassador extraordinary to Portugal. The first, signed in May, was a military alliance that cemented allegiances in the War of Spanish Succession, and was a 4-party treaty negotiated by Karl Ernst, Graf von Waldstein for the emperor, Francisco van Schonenberg (AKA Jacob Abraham Belmonte, c.q. Francesco Belmonte) for the United Provinces,[19] and King Pedro II for Portugal, with Methuen's son Sir Paul Methuen (1672–1757) aiding him.[20] The second one, the more well-known trade treaty, was a 2-party treaty signed on 27 December for England by Methuen and for Portugal by Manuel Teles da Silva, 3rd Marquis of Alegrete (1682–1736).[21][22]

The early years of the War of Spanish Succession, in Flanders, had been rather fruitless. The Tory Party in England was concerned about the cost of the war, and felt that naval warfare was a much cheaper option, with greater potential for success. Portugal offered the advantage of deep-water ports near the Mediterranean which could be used to counter the French Naval base at Toulon.

Treaty

There were three major elements to the Methuen Treaties. The first was the establishment of the war aims of the Grand Alliance.[23] Secondly, the agreement meant that Spain would become a new theatre of war. Finally, it regulated the establishment of trade relations, especially between England and Portugal.[11][24]

Until 1703 the Grand Alliance had never established any formal war aims. The Methuen Treaties changed this as it confirmed that the alliance would try to secure the entire Spanish Empire for Charles of Austria, the Habsburg claimant to the Spanish thrones.[25][26]

The first treaty also established the numbers of troops the various countries would provide to fight the campaign in Spain.[27] The Portuguese also insisted that Archduke Charles would come to Portugal to lead the forces in order to ensure full allied commitment to the war in Spain.[17][27]

The second treaty, signed on 27 December 1703[22] (popularly known as the "Port Wine Treaty") helped to establish trading relations between England and Portugal.[24] The terms of it allowed English woollen cloth to be admitted into Portugal free of duty; in return, Portuguese wines imported into England would be subject to a third less duty than wines imported from France.[23][28] This was particularly important in helping the development of the port industry.[29] As England was at war with France, it became increasingly difficult to acquire wine,[9] and so port started to become a popular replacement.

Ireland 1780s

The Kingdom of Ireland imported Portuguese wine at the low Methuen tariffs, but was banned under the Navigation Acts from exporting. In 1779, Ireland was granted "free trade", but Portugal imposed higher tariffs on Irish textile imports than on English ones, arguing it was outside the terms of the Methuen treaty. This was a tactic in Portugal's broader attempt to make Britain renegotiate the Methuen treaty. As the dispute dragged on, Ireland imposed higher tariffs on Portuguese goods, and the Irish Volunteers' 1782 Dungannon resolutions included calls for a boycott of its wines.[30] The 1786 Eden Agreement between Britain and France caused Portugal to relent in 1787 and allow Ireland low tariffs.[31]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Marques, Antonio Henrique R. de Oliveira (1976). History of Portugal. p. 386. https://archive.org/details/historyofportuga1976marq/page/n309/mode/2up?.

- ↑ Francis 1966, pp. 196–198.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Lains, Pedro; Freire Costa, Leonor; Münch Miranda, Susana (2016). An Economic History of Portugal, 1143–2010. Cambridge University Press. p. 200. ISBN 9781107035546. https://www.ics.ulisboa.pt/fcteval/books/Lains16.pdf. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ↑ Francis 1966, p. 200.

- ↑ Robinson, Joan (1979). Aspects of Development and Underdevelopment. Cambridge University Press. p. 103. https://archive.org/details/aspectsofdevelop0000robi/page/102/mode/2up. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ↑ Marques, Antonio Henrique R. de Oliveira (1976). History of Portugal. p. 385. https://archive.org/details/historyofportuga1976marq/page/n309/mode/2up?.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Francis, A. D. (1966). The Methuens and Portugal, 1691-1708. p. 201. https://archive.org/details/methuensportugal0000fran_a3z8/page/200/mode/2up. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ↑ McMurdo, Edward (1889). The history of Portugal, from the Commencement of the Monarchy to the Reign of Alfonso III. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington. p. 470. https://archive.org/details/historyportugal05mcmugoog/page/n10/mode/2up?. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Livermore, H.V. (1969). A New History of Portugal. Cambridge University Press. p. 217. ISBN 9780521095716. https://archive.org/details/newhistoryofport0000unse_y9g3/page/n9/mode/2up.

- ↑ Lains, Pedro; Freire Costa, Leonor; Münch Miranda, Susana (2016). An Economic History of Portugal, 1143–2010. Cambridge University Press. p. 198. ISBN 9781107035546. https://www.ics.ulisboa.pt/fcteval/books/Lains16.pdf. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Stephens, H. Morse (1891). The Story of Portugal. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 338–340. https://archive.org/details/storyofportugal00step/page/n7/mode/2up?. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- ↑ Lains, Pedro; Freire Costa, Leonor; Münch Miranda, Susana (2016). An Economic History of Portugal, 1143–2010. Cambridge University Press. p. 213. ISBN 9781107035546. https://www.ics.ulisboa.pt/fcteval/books/Lains16.pdf. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ↑ Francis 1966, p. 336.

- ↑ Kamen, Henry (1969). The War of Succession in Spain, 1700-15. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. pp. 4, 248. https://archive.org/details/warofsuccessioni0000kame/page/4/mode/2up. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ↑ McMurdo 1889, p. 454.

- ↑ Livermore 1969, pp. 202–203.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Livermore 1969, p. 203.

- ↑ Ball, Francis Elrington (1926). The judges in Ireland, 1221-1921. p. 14. https://archive.org/details/judgesinireland10002ball/page/14/mode/2up. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ↑ 1.02.04 Inventaris van het archief van F. van Schonenberg [levensjaren 1653–1717]: Gezant in Spanje en Portugal, 1678–1716

- ↑ McMurdo 1889, p. 456.

- ↑ The Treaties of the War of the Spanish Succession: An Historical and Critical Dictionary by Linda Frey and Marsha Frey, 1995, p. 290

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 McMurdo 1889, p. 455.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Dyer, Thomas Henry (1877). Modern Europe Vol. 3, Ed. 2nd. London: George Bell and Sons. p. 461. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.110000/page/n479/mode/2up. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Frey & Frey 1983, p. 68.

- ↑ Gregg, Edward (1984). Queen Anne. ARK Paperbacks. p. 172. https://archive.org/details/queenanne0000greg_m3q7/page/n5/mode/2up. Retrieved 31 October 2023.

- ↑ Kamen 1969, p. 10.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Frey, Linda; Frey, Marsha (1983). A Question of Empire: Leopold I and the War of Spanish Succession 1701-1705. pp. 65–66. https://archive.org/details/questionofempire0000lind/page/66/mode/2up.

- ↑ Lains, Pedro; Freire Costa, Leonor; Münch Miranda, Susana (2016). An Economic History of Portugal, 1143–2010. Cambridge University Press. p. 176. ISBN 9781107035546. https://www.ics.ulisboa.pt/fcteval/books/Lains16.pdf. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ↑ Lains, Pedro; Freire Costa, Leonor; Münch Miranda, Susana (2016). An Economic History of Portugal, 1143–2010. Cambridge University Press. pp. 177–179. ISBN 9781107035546. https://www.ics.ulisboa.pt/fcteval/books/Lains16.pdf. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ↑ Wilson, C. H. (1782). A compleat collection of the resolutions of the volunteers, grand juries, &c of Ireland, which followed the celebrated resolves of the first Dungannon diet: To which is prefixed a train of historical facts relative to the kingdom, from the invasion of Henry II. down, with the history of volunteering, &c. Printed by J. Hill. pp. 1–7. https://books.google.com/books?id=JHwDAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA1. Retrieved 21 November 2013. "That the court of Portugal have acted towards this kingdom, being a part of the British Empire, in such a manner as to call upon us to declare, and pledge ourselves to each other, that we will not consume any wine of the growth of Portugal, and that we will, to the extent of our influence, prevent the use of said wine, save and except the wine at present in this kingdom, until such time as our exports shall be received in the kingdom of Portugal, as the manufactures of part of the British empire."

- ↑ Kelly, James (1990). "The Irish Trade Dispute with Portugal 1780–87". Studia Hibernica (Liverpool University Press) (25): 7–48.

Further reading

- Francis, A.D. "John Methuen and the Anglo-Portuguese Treaties of 1703". The Historical Journal Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 103–124.

|

KSF

KSF