Option

Topic: Finance

From HandWiki - Reading time: 27 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 27 min

| Financial markets |

|---|

|

| Bond market |

| Stock market |

| Other markets |

| Over-the-counter (off-exchange) |

| Trading |

| Related areas |

In finance, an option is a contract which conveys to its owner, the holder, the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell a specific quantity of an underlying asset or instrument at a specified strike price on or before a specified date, depending on the style of the option. Options are typically acquired by purchase, as a form of compensation, or as part of a complex financial transaction. Thus, they are also a form of asset and have a valuation that may depend on a complex relationship between underlying asset price, time until expiration, market volatility, the risk-free rate of interest, and the strike price of the option. Options may be traded between private parties in over-the-counter (OTC) transactions, or they may be exchange-traded in live, public markets in the form of standardized contracts.

Definition and application

An option is a contract that allows the holder the right to buy or sell an underlying asset or financial instrument at a specified strike price on or before a specified date, depending on the form of the option. Selling or exercising an option before expiry typically requires a buyer to pick the contract up at the agreed upon price. The strike price may be set by reference to the spot price (market price) of the underlying security or commodity on the day an option is issued, or it may be fixed at a discount or at a premium. The issuer has the corresponding obligation to fulfill the transaction (to sell or buy) if the holder "exercises" the option. An option that conveys to the holder the right to buy at a specified price is referred to as a call, while one that conveys the right to sell at a specified price is known as a put.

The issuer may grant an option to a buyer as part of another transaction (such as a share issue or as part of an employee incentive scheme), or the buyer may pay a premium to the issuer for the option. A call option would normally be exercised only when the strike price is below the market value of the underlying asset, while a put option would normally be exercised only when the strike price is above the market value. When an option is exercised, the cost to the option holder is the strike price of the asset acquired plus the premium, if any, paid to the issuer. If the option's expiration date passes without the option being exercised, the option expires, and the holder forfeits the premium paid to the issuer. In any case, the premium is income to the issuer, and normally a capital loss to the option holder.

The holder of an option may on-sell the option to a third party in a secondary market, in either an over-the-counter transaction or on an options exchange, depending on the option. The market price of an American-style option normally closely follows that of the underlying stock being the difference between the market price of the stock and the strike price of the option. The actual market price of the option may vary depending on a number of factors, such as a significant option holder needing to sell the option due to the expiration date approaching and not having the financial resources to exercise the option, or a buyer in the market trying to amass a large option holding. The ownership of an option does not generally entitle the holder to any rights associated with the underlying asset, such as voting rights or any income from the underlying asset, such as a dividend.

History

Historical uses of options

Contracts similar to options have been used since ancient times.[1] The first reputed option buyer was the Ancient Greece mathematician and philosopher Thales of Miletus. On a certain occasion, it was predicted that the season's olive harvest would be larger than usual, and during the off-season, he acquired the right to use a number of olive presses the following spring. When spring came and the olive harvest was larger than expected, he exercised his options and then rented the presses out at a much higher price than he paid for his 'option'.[2][3]

The 1688 book Confusion of Confusions describes the trading of "opsies" on the Amsterdam stock exchange (now Euronext), explaining that "there will be only limited risks to you, while the gain may surpass all your imaginings and hopes."[4]

In London, puts and "refusals" (calls) first became well-known trading instruments in the 1690s during the reign of William and Mary.[5] Privileges were options sold over the counter in nineteenth century America, with both puts and calls on shares offered by specialized dealers. Their exercise price was fixed at a rounded-off market price on the day or week that the option was bought, and the expiry date was generally three months after purchase. They were not traded in secondary markets.

In the real estate market, call options have long been used to assemble large parcels of land from separate owners; e.g., a developer pays for the right to buy several adjacent plots, but is not obligated to buy these plots and might not unless they can buy all the plots in the entire parcel. Additionally, purchase of real property, like houses, requires a buyer paying the seller into an escrow account an earnest payment, which offers the buyer the right to buy the property at the set terms, including the purchase price.[citation needed]

In the motion picture industry, film or theatrical producers often buy an option giving the right – but not the obligation – to dramatize a specific book or script.

Lines of credit give the potential borrower the right – but not the obligation – to borrow within a specified time period.

Many choices, or embedded options, have traditionally been included in bond contracts. For example, many bonds are convertible into common stock at the buyer's option, or may be called (bought back) at specified prices at the issuer's option. Mortgage borrowers have long had the option to repay the loan early, which corresponds to a callable bond option.

Modern stock options

Options contracts have been known for decades. The Chicago Board Options Exchange was established in 1973, which set up a regime using standardized forms and terms and trade through a guaranteed clearing house. Trading activity and academic interest has increased since then.

Today, many options are created in a standardized form and traded through clearing houses on regulated options exchanges, while other over-the-counter options are written as bilateral, customized contracts between a single buyer and seller, one or both of which may be a dealer or market-maker. Options are part of a larger class of financial instruments known as derivative products, or simply, derivatives.[6][7]

Contract specifications

A financial option is a contract between two counterparties with the terms of the option specified in a term sheet. Option contracts may be quite complicated; however, at minimum, they usually contain the following specifications:[8]

- whether the option holder has the right to buy (a call option) or the right to sell (a put option)

- the quantity and class of the underlying asset(s) (e.g., 100 shares of XYZ Co. B stock)

- the strike price, also known as the exercise price, which is the price at which the underlying transaction will occur upon exercise

- the expiration date, or expiry, which is the last date the option can be exercised

- the settlement terms, for instance whether the writer must deliver the actual asset on exercise, or may simply tender the equivalent cash amount

- the terms by which the option is quoted in the market to convert the quoted price into the actual premium – the total amount paid by the holder to the writer

Option trading

Forms of trading

Exchange-traded options

Exchange-traded options (also called "listed options") are a class of exchange-traded derivatives. Exchange-traded options have standardized contracts, and are settled through a clearing house with fulfillment guaranteed by the Options Clearing Corporation (OCC). Since the contracts are standardized, accurate pricing models are often available. Exchange-traded options include:[9][10]

- Stock options

- Bond options and other interest rate options

- Stock market index options or, simply, index options

- Options on futures contracts and

- Callable bull/bear contract

Over-the-counter options

Over-the-counter options (OTC options, also called "dealer options") are traded between two private parties, and are not listed on an exchange. The terms of an OTC option are unrestricted and may be individually tailored to meet any business need. In general, the option writer is a well-capitalized institution (in order to prevent the credit risk). Option types commonly traded over the counter include:

By avoiding an exchange, users of OTC options can narrowly tailor the terms of the option contract to suit individual business requirements. In addition, OTC option transactions generally do not need to be advertised to the market and face little or no regulatory requirements. However, OTC counterparties must establish credit lines with each other, and conform to each other's clearing and settlement procedures.

With few exceptions,[11] there are no secondary markets for employee stock options. These must either be exercised by the original grantee or allowed to expire.

Exchange trading

The most common way to trade options is via standardized options contracts that are listed by various futures and options exchanges. [12] Listings and prices are tracked and can be looked up by ticker symbol. By publishing continuous, live markets for option prices, an exchange enables independent parties to engage in price discovery and execute transactions. As an intermediary to both sides of the transaction, the benefits the exchange provides to the transaction include:

- Fulfillment of the contract is backed by the credit of the exchange, which typically has the highest rating (AAA),

- Counterparties remain anonymous,

- Enforcement of market regulation to ensure fairness and transparency, and

- Maintenance of orderly markets, especially during fast trading conditions.

Basic trades (American style)

These trades are described from the point of view of a speculator. If they are combined with other positions, they can also be used in hedging. An option contract in US markets usually represents 100 shares of the underlying security.[13][14]

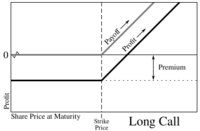

Long call

A trader who expects a stock's price to increase can buy a call option to purchase the stock at a fixed price (strike price) at a later date, rather than purchase the stock outright. The cash outlay on the option is the premium. The trader would have no obligation to buy the stock, but only has the right to do so on or before the expiration date. The risk of loss would be limited to the premium paid, unlike the possible loss had the stock been bought outright.

The holder of an American-style call option can sell the option holding at any time until the expiration date, and would consider doing so when the stock's spot price is above the exercise price, especially if the holder expects the price of the option to drop. By selling the option early in that situation, the trader can realise an immediate profit. Alternatively, the trader can exercise the option – for example, if there is no secondary market for the options – and then sell the stock, realising a profit. A trader would make a profit if the spot price of the shares rises by more than the premium. For example, if the exercise price is 100 and premium paid is 10, then if the spot price of 100 rises to only 110 the transaction is break-even; an increase in stock price above 110 produces a profit.

If the stock price at expiration is lower than the exercise price, the holder of the option at that time will let the call contract expire and lose only the premium (or the price paid on transfer).

Long put

A trader who expects a stock's price to decrease can buy a put option to sell the stock at a fixed price (strike price) at a later date. The trader is under no obligation to sell the stock, but has the right to do so on or before the expiration date. If the stock price at expiration is below the exercise price by more than the premium paid, the trader makes a profit. If the stock price at expiration is above the exercise price, the trader lets the put contract expire, and loses only the premium paid. In the transaction, the premium also plays a role as it enhances the break-even point. For example, if the exercise price is 100 and the premium paid is 10, then a spot price between 90 and 100 is not profitable. The trader makes a profit only if the spot price is below 90.

The trader exercising a put option on a stock does not need to own the underlying asset, because most stocks can be shorted.

Short call

A trader who expects a stock's price to decrease can sell the stock short or instead sell, or "write", a call. The trader selling a call has an obligation to sell the stock to the call buyer at a fixed price ("strike price"). If the seller does not own the stock when the option is exercised, they are obligated to purchase the stock in the market at the prevailing market price. If the stock price decreases, the seller of the call (call writer) makes a profit in the amount of the premium. If the stock price increases over the strike price by more than the amount of the premium, the seller loses money, with the potential loss being unlimited.

Short put

A trader who expects a stock's price to increase can buy the stock or instead sell, or "write", a put. The trader selling a put has an obligation to buy the stock from the put buyer at a fixed price ("strike price"). If the stock price at expiration is above the strike price, the seller of the put (put writer) makes a profit in the amount of the premium. If the stock price at expiration is below the strike price by more than the amount of the premium, the trader loses money, with the potential loss being up to the strike price minus the premium. A benchmark index for the performance of a cash-secured short put option position is the CBOE S&P 500 PutWrite Index (ticker PUT).

Options strategies

Combining any of the four basic kinds of option trades (possibly with different exercise prices and maturities) and the two basic kinds of stock trades (long and short) allows a variety of options strategies. Simple strategies usually combine only a few trades, while more complicated strategies can combine several.

Strategies are often used to engineer a particular risk profile to movements in the underlying security. For example, buying a butterfly spread (long one X1 call, short two X2 calls, and long one X3 call) allows a trader to profit if the stock price on the expiration date is near the middle exercise price, X2, and does not expose the trader to a large loss.

A condor is a strategy that is similar to a butterfly spread, but with different strikes for the short options – offering a larger likelihood of profit but with a lower net credit compared to the butterfly spread.

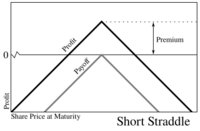

Selling a straddle (selling both a put and a call at the same exercise price) would give a trader a greater profit than a butterfly if the final stock price is near the exercise price, but might result in a large loss.

Similar to the straddle is the strangle which is also constructed by a call and a put, but whose strikes are different, reducing the net debit of the trade, but also reducing the risk of loss in the trade.

One well-known strategy is the covered call, in which a trader buys a stock (or holds a previously-purchased stock position), and sells a call. (This can be contrasted with a naked call. See also naked put.) If the stock price rises above the exercise price, the call will be exercised and the trader will get a fixed profit. If the stock price falls, the call will not be exercised, and any loss incurred to the trader will be partially offset by the premium received from selling the call. Overall, the payoffs match the payoffs from selling a put. This relationship is known as put–call parity and offers insights for financial theory. A benchmark index for the performance of a buy-write strategy is the CBOE S&P 500 BuyWrite Index (ticker symbol BXM).

Another very common strategy is the protective put, in which a trader buys a stock (or holds a previously-purchased long stock position), and buys a put. This strategy acts as an insurance when investing long on the underlying stock, hedging the investor's potential losses, but also shrinking an otherwise larger profit, if just purchasing the stock without the put. The maximum profit of a protective put is theoretically unlimited as the strategy involves being long on the underlying stock. The maximum loss is limited to the purchase price of the underlying stock less the strike price of the put option and the premium paid. A protective put is also known as a married put.

Types

Options can be classified in a few ways.

According to the option rights

- Call options give the holder the right – but not the obligation – to buy something at a specific price for a specific time period.

- Put options give the holder the right – but not the obligation – to sell something at a specific price for a specific time period.

According to the delivery type

- Physically delivery option requires actual delivery of the goods or stocks to take place.

- Cash-settled option is settled in resulting cash payment.

According to the underlying assets

- Equity option

- Bond option

- Future option

- Index option

- Commodity option

- Currency option

- Swap option

Other option types

Another important class of options, particularly in the U.S., are employee stock options, which are awarded by a company to their employees as a form of incentive compensation. Other types of options exist in many financial contracts, for example real estate options are often used to assemble large parcels of land, and prepayment options are usually included in mortgage loans. However, many of the valuation and risk management principles apply across all financial options.

Option styles

Options are classified into a number of styles, the most common of which are:

- American option – an option that may be exercised on any trading day on or before expiration.

- European option – an option that may only be exercised on expiry.

These are often described as vanilla options. Other styles include:

- Bermudan option – an option that may be exercised only on specified dates on or before expiration.

- Asian option – an option whose payoff is determined by the average underlying price over some preset time period.

- Barrier option – any option with the general characteristic that the underlying security's price must pass a certain level or "barrier" before it can be exercised.

- Binary option – An all-or-nothing option that pays the full amount if the underlying security meets the defined condition on expiration otherwise it expires.

- Exotic option – any of a broad category of options that may include complex financial structures.[15]

Valuation

Because the values of option contracts depend on a number of different variables in addition to the value of the underlying asset, they are complex to value. There are many pricing models in use, although all essentially incorporate the concepts of rational pricing (i.e. risk neutrality), moneyness, option time value, and put–call parity.

The valuation itself combines a model of the behavior ("process") of the underlying price with a mathematical method which returns the premium as a function of the assumed behavior. The models range from the (prototypical) Black–Scholes model for equities,[16][unreliable source?][17] to the Heath–Jarrow–Morton framework for interest rates, to the Heston model where volatility itself is considered stochastic. See Asset pricing for a listing of the various models here.

Basic decomposition

In its most basic terms, the value of an option is commonly decomposed into two parts:

- The first part is the intrinsic value, which is defined as the difference between the market value of the underlying, and the strike price of the given option

- The second part is the time value, which depends on a set of other factors which, through a multi-variable, non-linear interrelationship, reflect the discounted expected value of that difference at expiration.

Valuation models

As above, the value of the option is estimated using a variety of quantitative techniques, all based on the principle of risk-neutral pricing, and using stochastic calculus in their solution. The most basic model is the Black–Scholes model. More sophisticated models are used to model the volatility smile. These models are implemented using a variety of numerical techniques.[18] In general, standard option valuation models depend on the following factors:

- The current market price of the underlying security

- The strike price of the option, particularly in relation to the current market price of the underlying (in the money vs. out of the money)

- The cost of holding a position in the underlying security, including interest and dividends

- The time to expiration together with any restrictions on when exercise may occur

- an estimate of the future volatility of the underlying security's price over the life of the option

More advanced models can require additional factors, such as an estimate of how volatility changes over time and for various underlying price levels, or the dynamics of stochastic interest rates.

The following are some of the principal valuation techniques used in practice to evaluate option contracts.

Black–Scholes

Following early work by Louis Bachelier and later work by Robert C. Merton, Fischer Black and Myron Scholes made a major breakthrough by deriving a differential equation that must be satisfied by the price of any derivative dependent on a non-dividend-paying stock. By employing the technique of constructing a risk neutral portfolio that replicates the returns of holding an option, Black and Scholes produced a closed-form solution for a European option's theoretical price.[19] At the same time, the model generates hedge parameters necessary for effective risk management of option holdings.

While the ideas behind the Black–Scholes model were ground-breaking and eventually led to Scholes and Merton receiving the Swedish Central Bank's associated Prize for Achievement in Economics (a.k.a., the Nobel Prize in Economics),[20] the application of the model in actual options trading is clumsy because of the assumptions of continuous trading, constant volatility, and a constant interest rate. Nevertheless, the Black–Scholes model is still one of the most important methods and foundations for the existing financial market in which the result is within the reasonable range.[21]

Stochastic volatility models

Since the market crash of 1987, it has been observed that market implied volatility for options of lower strike prices are typically higher than for higher strike prices, suggesting that volatility varies both for time and for the price level of the underlying security – a so-called volatility smile; and with a time dimension, a volatility surface.

The main approach here is to treat volatility as stochastic, with the resultant stochastic volatility models, and the Heston model as prototype;[22] see #Risk-neutral measure for a discussion of the logic. Other models include the CEV and SABR volatility models. One principal advantage of the Heston model, however, is that it can be solved in closed-form, while other stochastic volatility models require complex numerical methods.[22]

An alternate, though related, approach is to apply a local volatility model, where volatility is treated as a deterministic function of both the current asset level and of time . As such, a local volatility model is a generalisation of the Black–Scholes model, where the volatility is a constant. The concept was developed when Bruno Dupire[23] and Emanuel Derman and Iraj Kani[24] noted that there is a unique diffusion process consistent with the risk neutral densities derived from the market prices of European options. See #Development for discussion.

Short-rate models

For the valuation of bond options, swaptions (i.e. options on swaps), and interest rate cap and floors (effectively options on the interest rate) various short-rate models have been developed (applicable, in fact, to interest rate derivatives generally). The best known of these are Black-Derman-Toy and Hull–White.[25] These models describe the future evolution of interest rates by describing the future evolution of the short rate. The other major framework for interest rate modelling is the Heath–Jarrow–Morton framework (HJM). The distinction is that HJM gives an analytical description of the entire yield curve, rather than just the short rate. (The HJM framework incorporates the Brace–Gatarek–Musiela model and market models. And some of the short rate models can be straightforwardly expressed in the HJM framework.) For some purposes, e.g., valuation of mortgage-backed securities, this can be a big simplification; regardless, the framework is often preferred for models of higher dimension. Note that for the simpler options here, i.e. those mentioned initially, the Black model can instead be employed, with certain assumptions.

Model implementation

Once a valuation model has been chosen, there are a number of different techniques used to implement the models.

Analytic techniques

In some cases, one can take the mathematical model and using analytical methods, develop closed form solutions such as the Black–Scholes model and the Black model. The resulting solutions are readily computable, as are their "Greeks". Although the Roll–Geske–Whaley model applies to an American call with one dividend, for other cases of American options, closed form solutions are not available; approximations here include Barone-Adesi and Whaley, Bjerksund and Stensland and others.

Binomial tree pricing model

Closely following the derivation of Black and Scholes, John Cox, Stephen Ross and Mark Rubinstein developed the original version of the binomial options pricing model.[26][27] It models the dynamics of the option's theoretical value for discrete time intervals over the option's life. The model starts with a binomial tree of discrete future possible underlying stock prices. By constructing a riskless portfolio of an option and stock (as in the Black–Scholes model) a simple formula can be used to find the option price at each node in the tree. This value can approximate the theoretical value produced by Black–Scholes, to the desired degree of precision. However, the binomial model is considered more accurate than Black–Scholes because it is more flexible; e.g., discrete future dividend payments can be modeled correctly at the proper forward time steps, and American options can be modeled as well as European ones. Binomial models are widely used by professional option traders. The trinomial tree is a similar model, allowing for an up, down or stable path; although considered more accurate, particularly when fewer time-steps are modelled, it is less commonly used as its implementation is more complex. For a more general discussion, as well as for application to commodities, interest rates and hybrid instruments, see Lattice model.

Monte Carlo models

For many classes of options, traditional valuation techniques are intractable because of the complexity of the instrument. In these cases, a Monte Carlo approach may often be useful. Rather than attempt to solve the differential equations of motion that describe the option's value in relation to the underlying security's price, a Monte Carlo model uses simulation to generate random price paths of the underlying asset, each of which results in a payoff for the option. The average of these payoffs can be discounted to yield an expectation value for the option.[28] Note though, that despite its flexibility, using simulation for American styled options is somewhat more complex than for lattice based models.

Finite difference models

The equations used to model the option are often expressed as partial differential equations (see for example Black–Scholes equation). Once expressed in this form, a finite difference model can be derived, and the valuation obtained. A number of implementations of finite difference methods exist for option valuation, including: explicit finite difference, implicit finite difference and the Crank–Nicolson method. A trinomial tree option pricing model can be shown to be a simplified application of the explicit finite difference method. Although the finite difference approach is mathematically sophisticated, it is particularly useful where changes are assumed over time in model inputs – for example dividend yield, risk-free rate, or volatility, or some combination of these – that are not tractable in closed form.

Other models

Other numerical implementations which have been used to value options include finite element methods.

Risks

| Example:

A call option (also known as a CO) expiring in 99 days on 100 shares of XYZ stock is struck at $50, with XYZ currently trading at $48. With future realized volatility over the life of the option estimated at 25%, the theoretical value of the option is $1.89. The hedge parameters , , , are (0.439, 0.0631, 9.6, and −0.022), respectively. Assume that on the following day, XYZ stock rises to $48.5 and volatility falls to 23.5%. We can calculate the estimated value of the call option by applying the hedge parameters to the new model inputs as: Under this scenario, the value of the option increases by $0.0614 to $1.9514, realizing a profit of $6.14. Note that for a delta neutral portfolio, whereby the trader had also sold 44 shares of XYZ stock as a hedge, the net loss under the same scenario would be ($15.86). |

As with all securities, trading options entails the risk of the option's value changing over time. However, unlike traditional securities, the return from holding an option varies non-linearly with the value of the underlying and other factors. Therefore, the risks associated with holding options are more complicated to understand and predict.

In general, the change in the value of an option can be derived from Itô's lemma as:

where the Greeks , , and are the standard hedge parameters calculated from an option valuation model, such as Black–Scholes, and , and are unit changes in the underlying's price, the underlying's volatility and time, respectively.

Thus, at any point in time, one can estimate the risk inherent in holding an option by calculating its hedge parameters and then estimating the expected change in the model inputs, , and , provided the changes in these values are small. This technique can be used effectively to understand and manage the risks associated with standard options. For instance, by offsetting a holding in an option with the quantity of shares in the underlying, a trader can form a delta neutral portfolio that is hedged from loss for small changes in the underlying's price. The corresponding price sensitivity formula for this portfolio is:

Pin risk

A special situation called pin risk can arise when the underlying closes at or very close to the option's strike value on the last day the option is traded prior to expiration. The option writer (seller) may not know with certainty whether or not the option will actually be exercised or be allowed to expire. Therefore, the option writer may end up with a large, unwanted residual position in the underlying when the markets open on the next trading day after expiration, regardless of his or her best efforts to avoid such a residual.

Counterparty risk

A further, often ignored, risk in derivatives such as options is counterparty risk. In an option contract this risk is that the seller will not sell or buy the underlying asset as agreed. The risk can be minimized by using a financially strong intermediary able to make good on the trade, but in a major panic or crash the number of defaults can overwhelm even the strongest intermediaries.

Options approval levels

To limit risk, brokers use access control systems to restrict traders from executing certain options strategies that would not be suitable for them. Brokers generally offer about four or five approval levels, with the lowest level offering the lowest risk and the highest level offering the highest risk. The actual numbers of levels, and the specific options strategies permitted at each level, vary between brokers. Brokers may also have their own specific vetting criteria, but they are usually based on factors such as the trader's annual salary and net worth, trading experience, and investment goals (capital preservation, income, growth, or speculation). For example, a trader with a low salary and net worth, little trading experience, and only concerned about preserving capital generally would not be permitted to execute high-risk strategies like naked calls and naked puts. Traders can update their information when requesting permission to upgrade to a higher approval level.[29]

See also

- American Stock Exchange

- Area yield options contract

- Ascot

- Chicago Board Options Exchange

- Dilutive security

- Eurex

- Euronext.liffe

- International Securities Exchange

- NYSE Arca

- Philadelphia Stock Exchange

- LEAPS

- Options backdating

- Options Clearing Corporation

- Options spread

- Options strategy

- Option symbol

- Real options analysis

- PnL Explained

- Pin risk (options)

- XVA

References

- ↑ Abraham, Stephan (May 13, 2010). "History of Financial Options - Investopedia". http://www.investopedia.com/articles/optioninvestor/10/history-options-futures.asp.

- ↑ Mattias Sander. Bondesson's Representation of the Variance Gamma Model and Monte Carlo Option Pricing. Lunds Tekniska Högskola 2008

- ↑ Aristotle. Politics.

- ↑ Josef de la Vega. Confusión de Confusiones. 1688. Portions Descriptive of the Amsterdam Stock Exchange Selected and Translated by Professor Hermann Kellenbenz. Baker Library, Harvard Graduate School Of Business Administration, Boston, Massachusetts.

- ↑ Smith, B. Mark (2003), History of the Global Stock Market from Ancient Rome to Silicon Valley, University of Chicago Press, p. 20, ISBN 0-226-76404-4

- ↑ Brealey, Richard A.; Myers, Stewart (2003), Principles of Corporate Finance (7th ed.), McGraw-Hill, Chapter 20

- ↑ Hull, John C. (2005), Options, Futures and Other Derivatives (excerpt by Fan Zhang) (6th ed.), Prentice-Hall, p. 6, ISBN 0-13-149908-4, http://fan.zhang.gl/ecref/options, retrieved April 21, 2008

- ↑ Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options, Options Clearing Corporation, https://www.theocc.com/getmedia/a151a9ae-d784-4a15-bdeb-23a029f50b70/riskstoc.pdf;, retrieved July 15, 2020

- ↑ Trade CME Products, Chicago Mercantile Exchange, http://www.cme.com/trading/, retrieved June 21, 2007

- ↑ ISE Traded Products, International Securities Exchange, http://www.iseoptions.com/products_traded.aspx, retrieved June 21, 2007

- ↑ Elinor Mills (December 12, 2006), Google unveils unorthodox stock option auction, CNet, http://news.cnet.com/Google+unveils+unorthodox+stock+option+auction/2100-1030_3-6143227.html, retrieved June 19, 2007

- ↑ Harris, Larry (2003), Trading and Exchanges, Oxford University Press, pp.26–27

- ↑ invest-faq or Law & Valuation for typical size of option contract

- ↑ "Understanding Stock Options". The Options Clearing Corporation and CBOE. https://www.cboe.com/LearnCenter/pdf/understanding.pdf.

- ↑ Fabozzi, Frank J. (2002). The Handbook of Financial Instruments (1st ed.). New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons. p. 471. ISBN 0-471-22092-2.

- ↑ Benhamou, Eric. "Options pre-Black Scholes". http://www.ericbenhamou.net/documents/Encyclo/Pre%20Black-Scholes.pdf.

- ↑ Black, Fischer; Scholes, Myron (1973). "The Pricing of Options and Corporate Liabilities". Journal of Political Economy 81 (3): 637–654. doi:10.1086/260062.

- ↑ Reilly, Frank K.; Brown, Keith C. (2003). Investment Analysis and Portfolio Management (7th ed.). Thomson Southwestern. Chapter 23.

- ↑ Black, Fischer and Myron S. Scholes. "The Pricing of Options and Corporate Liabilities", Journal of Political Economy, 81 (3), 637–654 (1973).

- ↑ Das, Satyajit (2006), Traders, Guns & Money: Knowns and unknowns in the dazzling world of derivatives (6th ed.), London: Prentice-Hall, Chapter 1 'Financial WMDs – derivatives demagoguery,' p.22, ISBN 978-0-273-70474-4, https://archive.org/details/tradersgunsmoney00dass_0

- ↑ Hull, John C. (2005), Options, Futures and Other Derivatives (6th ed.), Prentice-Hall, ISBN 0-13-149908-4

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Jim Gatheral (2006), The Volatility Surface, A Practitioner's Guide, Wiley Finance, ISBN 978-0-471-79251-2

- ↑ Bruno Dupire (July 2007). "Pricing with a Smile". Risk. http://www.risk.net/data/risk/pdf/technical/2007/risk20_0707_technical_volatility.pdf. Retrieved 2013-06-14.

- ↑ Derman, E.; Iraj Kani (January 1994). "Riding on a Smile". Quantitative Strategies Research Notes (Goldman Sachs). http://www.ederman.com/new/docs/gs-volatility_smile.pdf. Retrieved 2007-06-01.

- ↑ Fixed Income Analysis, p. 410, at Google Books

- ↑ Cox, J. C., Ross SA and Rubinstein M. 1979. Options pricing: a simplified approach, Journal of Financial Economics, 7:229–263.[1]

- ↑ Cox, John C.; Rubinstein, Mark (1985), Options Markets, Prentice-Hall, Chapter 5

- ↑ Crack, Timothy Falcon (2004), Basic Black–Scholes: Option Pricing and Trading, Timothy Crack, pp. 91–102, ISBN 0-9700552-2-6, http://www.BasicBlackScholes.com/

- ↑ "Investor Bulletin: Opening an Options Account". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. 18 March 2015. https://www.sec.gov/oiea/investor-alerts-bulletins/ib_openingoptionsaccount.

Further reading

- Fischer Black and Myron S. Scholes. "The Pricing of Options and Corporate Liabilities," Journal of Political Economy, 81 (3), 637–654 (1973).

- Feldman, Barry and Dhuv Roy. "Passive Options-Based Investment Strategies: The Case of the CBOE S&P 500 BuyWrite Index." The Journal of Investing, (Summer 2005).

- Kleinert, Hagen, Path Integrals in Quantum Mechanics, Statistics, Polymer Physics, and Financial Markets, 4th edition, World Scientific (Singapore, 2004); Paperback ISBN 981-238-107-4 (also available online: PDF-files)

- Hill, Joanne, Venkatesh Balasubramanian, Krag (Buzz) Gregory, and Ingrid Tierens. "Finding Alpha via Covered Index Writing." Financial Analysts Journal. (Sept.-Oct. 2006). pp. 29–46.

- Millman, Gregory J. (2008), David R. Henderson, ed., Futures and Options Markets (2nd ed.), Indianapolis: Library of Economics and Liberty, ISBN 978-0-86597-665-8, OCLC 237794267, http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/FuturesandOptionsMarkets.html

- Natenberg, Sheldon (2015). Option Volatility and Pricing: Advanced Trading Strategies and Techniques (Second ed.). New York. ISBN 978-0-07-181877-3.

- Moran, Matthew. "Risk-adjusted Performance for Derivatives-based Indexes – Tools to Help Stabilize Returns." The Journal of Indexes. (Fourth Quarter, 2002) pp. 34–40.

- Reilly, Frank and Keith C. Brown, Investment Analysis and Portfolio Management, 7th edition, Thompson Southwestern, 2003, pp. 994–5.

- Schneeweis, Thomas, and Richard Spurgin. "The Benefits of Index Option-Based Strategies for Institutional Portfolios" The Journal of Alternative Investments, (Spring 2001), pp. 44–52.

- Whaley, Robert. "Risk and Return of the CBOE BuyWrite Monthly Index" The Journal of Derivatives, (Winter 2002), pp. 35–42.

- Bloss, Michael; Ernst, Dietmar; Häcker Joachim (2008): Derivatives – An authoritative guide to derivatives for financial intermediaries and investors Oldenbourg Verlag München ISBN 978-3-486-58632-9

- Espen Gaarder Haug & Nassim Nicholas Taleb (2008): "Why We Have Never Used the Black–Scholes–Merton Option Pricing Formula"

KSF

KSF