World taxation system

Topic: Finance

From HandWiki - Reading time: 11 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 11 min

A world taxation system or global tax is a hypothetical system for the collection of taxes by a central international revenue service. The idea has garnered currency as a means of eliminating tax avoidance and tax competition; it has also aroused the ire of nationalists as an infringement upon national sovereignty.

Proposed international taxes

Financial transaction taxes

Discussion of a global financial transaction tax (FTT) increased in the 2000s, especially after the late-2000s recession, and especially in Europe. In 2010, a coalition of 50 charities and other NGOs began advocating for what they labelled a Robin Hood tax, which would tax transactions of stocks, bonds and other financial securities.

In 2011, the European Union (EU) proposed an EU-wide FTT; consensus, however, could not be reached among all EU countries. In 2013, 11 countries in the EU's Eurozone established the European Union financial transaction tax, estimated to generate €35 billion per year.[1]

In 2012, a group of UN experts recommended that the United Nations adopt a FTT, estimating that the tax could bring $48-$250 billion in revenue, to be channelled to "fighting poverty, reversing growing inequality, and compensating those whose lives have been devastated by the enduring global economic crisis".[2]

In the UK, bank taxes have been proposed as another means of worldwide taxation, as have been sales taxes. Proposals to combat the ongoing recession included the Financial stability contribution (FSC)[3][4] and Financial Activities Tax (FAT).[5] On August 30, 2009, British Financial Services Authority chairman Lord Adair Turner said it was "ridiculous" to think he would propose a new tax on London and not the rest of the world.[6] However, in May, and June 2010, the government of Canada expressed opposition to the bank tax becoming "global" in nature.[7]

Tobin tax

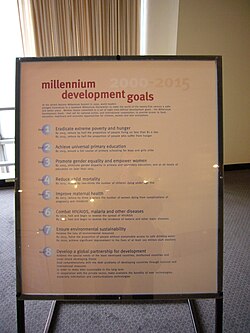

The Tobin tax is a tax on all conversions of money from one currency to another, proposed by Nobel Prize-winning American economist James Tobin. According to Dr. Stephen Spratt, "the revenues raised could be used for....international development objectives...such as meeting the Millennium Development Goals."[8] These are eight international development goals that 192 United Nations member states and at least 23 international organizations have agreed (in 2000) to achieve by the year 2015. They include reducing extreme poverty, reducing child mortality rates, fighting disease epidemics such as AIDS, and developing a global partnership for development.[9]

In 2000, a representative of a "pro-Tobin tax" NGO proposed the following: "In the face of increasing income disparity and social inequity, the Tobin Tax represents a rare opportunity to capture the enormous wealth of an untaxed sector and redirect it towards the public good. Conservative estimates show the tax could yield from $150-300 billion annually. The UN estimates that the cost of wiping out the worst forms of poverty and environmental destruction globally would be around $225 billion per year."[10]

At the UN September 2001 World Conference against Racism, when the issue of compensation for colonialism and slavery arose on the agenda, Fidel Castro, the President of Cuba, advocated the Tobin Tax to address that issue. (According to Cliff Kincaid, Castro advocated it "specifically in order to generate U.S. financial reparations to the rest of the world," however a closer reading of Castro's speech shows that he never did mention "the rest of the world" as being recipients of revenue.) Castro cited Holocaust reparations as a previously established precedent for the concept of reparations.[11][12]

Castro also suggested that the United Nations be the administrator of this tax, stating the following:

"May the tax suggested by Nobel Prize Laureate James Tobin be imposed in a reasonable and effective way on the current speculative operations accounting for trillions of US dollars every 24 hours, then the United Nations, which cannot go on depending on meager, inadequate, and belated donations and charities, will have one trillion US dollars annually to save and develop the world. Given the seriousness and urgency of the existing problems, which have become a real hazard for the very survival of our species on the planet, that is what would actually be needed before it is too late."[11]

On March 6, 2006, US Congressman Dr Ron Paul stated the following: "The United Nations remains determined to rob from wealthy countries and, after taking a big cut for itself, send what's left to the poor countries. Of course, most of this money will go to the very dictators whose reckless policies have impoverished their citizens. The UN global tax plan...resurrects the long-held dream of the 'Tobin Tax'. A dangerous precedent would be set, however: the idea that the UN possesses the legitimate taxing authority to fund its operations."[13]

Global wealth tax

The idea of a global wealth tax has been much discussed since the 2014 success of French economist Thomas Piketty's bestseller Capital in the Twenty-First Century.[14] In the book, Piketty proposes that because the rate of return on capital tends to exceed total growth, inequality will tend to rise forever without government intervention. The solution he proposed is a global tax on capital. He imagined that the tax would be zero for those with less than 1 million euros, 2% for those with more than 5 million, and 5-10% for those with more than 1 billion euros.[15] Piketty suggested the revenue could provide all global citizens with an endowment when they reach the age of 25 years.[16]

It has been estimated that for the US, a tax of 2% on fortunes greater than US$4 million would generate US$500 billion per year.[15] About half of that amount, about 300 billion per year, corresponds to the total developmental budget goal of 0.7% GNP of industrialised countries (see Millennium Development Goals), which would enable poorer countries to cross the threshold of economic competitivity in 15–20 years (cf. Jeffrey Sachs: The End of Poverty). Some 300 billion per year would also be necessary to limit global warming to +2 degrees Celsius and finance recovery from more frequent climate disasters. Expensive but probably inevitable strategies to slow global warming include renewable energy research, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and reforestation (or preventing deforestation).[17]

From the 2020s, Patriotic Millionaires, a group of high net worth individuals, began calling for governments to implement wealth taxes of those with extreme wealth. In 2023, they penned an open letter to political leaders attending Davos, stating "The solution is plain for all to see. You, our global representatives, have to tax us, the ultra rich, and you have to start now."[18] Oxfam said a tax of up to 5% on the world's multimillionaires and billionaires could raise $1.7tn a year, enough to lift 2 billion people out of poverty.[19]

Leading up to a 2023 finance summit in France, 100 leading economists signed a letter calling for a wealth tax on the world's richest people in order to help the poorest survive climate change.[20]

In 2024 Gabriel Zucman again proposed a push for a global wealth tax on centimillionaires and richer still high-net-worth individuals .[21][22]

International carbon tax

The Kyoto Protocol of 1997, which was signed by 192 countries, included a proposal for an International Emissions Trading scheme. Subsequently, this was superseded by Article 6 of the Paris Agreement which stated the principle of international carbon trading. Consequently, some national emissions trading schemes are theoretically compatible with those of other nations whose schemes have similar standards. In 2017, the EU agreed to link the European Union Emissions Trading System to the Switzerland emissions trading system.[23]

In order not to advantage countries without a carbon price, the EU has designed the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism to come into effect in 2026, which will place tariffs on imported goods which have not been subjected to a carbon price. Similar discussions have been ongoing in the US[24] and Australia[25] among others. The OECD has proposed creating an international framework for such carbon border adjustments to avoid trade competition.[26]

Kristalina Georgieva, managing director of the IMF, has proposed an international carbon price floor,[27] noting that four fifths of global emissions remain unpriced. However, this only requires revenue to be collected by national governments, so it not truly a global tax.

In the 2020s, there has been discussion of global carbon taxes among the international community, including the OECD, World Trade Organization and International Monetary Fund.[28] It was suggested that a uniform global carbon tax could eliminate the need for carbon border tariffs. Some research has suggested that such a proposal could be popular if the revenue generated by the tax is paid directly to citizens,[29] a payment known as a carbon dividend.

An alternative to a traditional international carbon tax is Cap and Share, also known as the Global Climate Plan. Under this framework, emission permits are auctioned to fossil fuel producers and other major emitters, and the revenues are distributed equally to all individuals worldwide. Although companies purchase the permits, the resulting costs are typically passed on to consumers through higher prices. This approach effectively transfers income from high emitters to low emitters, functioning as both a climate mitigation tool and a redistributive mechanism. Unlike a carbon tax, which sets the price and allows emissions to vary, Cap and Share fixes the total emissions limit and lets the market determine the price, ensuring adherence to a global carbon budget.[30]

Carbon tax for international shipping

By 2021, global industry-wide carbon taxes were supported by groups representing 90% of the shipping industry, including the International Chamber of Shipping, Bimco, Cruise Lines International Association and the World Shipping Council.[31] The International Maritime Organization reached agreement in 2022 that a global carbon tax for shipping should be established.[32] However, there is wide disagreement about the price level, with proposals ranging from $150 to just $2 per tonne of fuel.

In 2023, research from CE Delft found that global shipping emissions could be cut by between a third to a half by 2030 without harming international trade.[33] This was important since countries including China, India, Brazil and Saudi Arabia had expressed opposition to the tax, on the basis that it could put international trade at risk. The World Bank has estimated a shipping carbon tax could raise $50-60 billion per year,[34] which some countries have proposed be donated to a "loss and damage" fund,[35] to pay for damage caused by climate change.

By 2024, 47 countries supported the proposal, including the European Union, Canada, Japan and the Pacific Islands. Research suggested that low-carbon ammonia shipping could be unlocked at a $150 carbon price.[36]

Sovereignty Issues

In the US and other countries' nationalist movements, the idea of global taxation arouses ire in its perception by such circles as a potential infringement upon national sovereignty.[37]

See also

- World currency

- World citizen

- Tax treaty

- List of countries by tax rates

- Tax harmonization

- Tax equalization

References

- ↑ "EU approves financial transaction tax for 11 eurozone countries" (in en). 2013-01-22. http://www.theguardian.com/business/2013/jan/22/eu-approves-financial-transaction-tax-eurozone.

- ↑ "G-8 / EU: "A global financial transaction tax, a human rights imperative now more than ever"" (in en). https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2012/05/g-8-eu-global-financial-transaction-tax-human-rights-imperative-now-more.

- ↑ John Dillon (May 2010). "An Idea Whose Time Has Come: Adopt a Financial Transactions Tax". KAIROS Policy Briefing Paper No. 24 revised and updated. KAIROS. http://www.kairoscanada.org/en/ecojustice/news-list/news/archive/2010/04/browse/1/article/an-idea-whose-time-has-come-adopt-a-financial-transactions-tax/?tx_ttnews. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ↑ BBC (April 21, 2010). "IMF proposes two big new bank taxes to fund bail-outs". BBC. https://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/8633455.stm.

- ↑ Peter Thal Larsen (23 April 2010). "Low-FAT diet". Reuters Breaking News. http://www.breakingviews.com/2010/04/21/fat%20tax.aspx?sg=nytimes. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ↑ BBC (August 30, 2009). "Turner defends bank tax comments". BBC. https://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/8229500.stm.

- ↑ The Canadian Press (June 24, 2010). "Flaherty says global bank tax a distraction for G20". CTV news via The Canadian Press. https://www.ctvnews.ca/g20-split-on-stimulus-but-united-on-maternal-health-1.526295. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ↑ Dr. Stephen Spratt of Intelligence Capital (September 2006). "A Sterling Solution". Stamp Out Poverty report. Stamp Out Poverty Campaign. pp. 19. http://www.stampoutpoverty.org/?lid=9889. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ↑ Background page, United Nations Millennium Development Goals website, retrieved 16 June 2009.

- ↑ Robin Round (January–February 2000). "Time for Tobin!". New Internationalist. http://www.newint.org/issue320/tobin.htm. Retrieved 2009-12-17.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Fidel Castro (September 1, 2001). "Key address by Dr. Fidel Castro Ruz, President of the Republic of Cuba at the World Conference against racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance". United Nations. https://www.un.org/WCAR/statements/0109cubaE.htm. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ↑ Cliff Kincaid (October 6, 2009). "Progressives Back Obama Push for Global Tax". Accuracy in Media. http://www.aim.org/aim-column/progressives-back-obama-push-for-global-tax/. Retrieved 2010-01-29.

- ↑ Ron Paul (March 6, 2006). "International taxes?". The Ron Paul Library. http://ronpaullibrary.org/document.php?id=451. Retrieved 2010-01-26.

- ↑ "Thomas Piketty's Capital: everything you need to know about the surprise bestseller" (in en). 2014-04-28. http://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/apr/28/thomas-piketty-capital-surprise-bestseller.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Vinik, Danny (2014-04-24). "What Would the World Look Like with Piketty's Global Tax on Wealth?". The New Republic. ISSN 0028-6583. https://newrepublic.com/article/117499/heres-what-we-know-about-thomas-pikettys-wealth-capital-tax. Retrieved 2023-01-09.

- ↑ Coldiron, Kevin. "The Wealth Tax — When Thomas Piketty And Eleanor Shellstrop Agree, It's Time To Act" (in en). https://www.forbes.com/sites/kevincoldiron/2021/02/22/the-wealth-tax---when-thomas-piketty-and-eleanor-shellstrop-agree-its-time-to-act/.

- ↑ Richard Parncutt (July 13, 2012). "Global Wealth Tax". http://www.uni-graz.at/~parncutt/wealthtax.html.

- ↑ "'Tax us now': ultra-rich call on governments to introduce wealth taxes" (in en). 2023-01-18. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2023/jan/18/tax-us-now-ultra-rich-wealth-tax-davos.

- ↑ "As Davos kicks off, Oxfam calls for tax on food companies to reduce inequality" (in en-US). 16 January 2023. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/davos-opens-oxfam-tax-on-food-companies-inequality/.

- ↑ Harvey, Fiona (2023-06-19). "A wealth tax could help poorer countries tackle climate crisis, economists say" (in en-GB). The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/jun/19/wealth-tax-help-poorer-countries-tackle-climate-crisis-economists.

- ↑ "A blueprint for a coordinated minimum effective taxation standard for ultra-high-net-worth individuals". https://www.taxobservatory.eu/publication/a-blueprint-for-a-coordinated-minimum-effective-taxation-standard-for-ultra-high-net-worth-individuals/.

- ↑ "Top economist pitches global billionaire tax to G20 finance leaders". https://www.icij.org/investigations/pandora-papers/top-economist-pitches-global-billionaire-tax-to-g20-finance-leaders/.

- ↑ "International carbon market" (in en). https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/eu-emissions-trading-system-eu-ets/international-carbon-market_en.

- ↑ Taylor, Kira (2021-07-22). "US lawmakers push carbon border tariff similar to EU's CBAM" (in en-GB). https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/news/us-lawmakers-push-carbon-border-tariff-similar-to-eus-cbam/.

- ↑ "Carbon tariffs backed by union to protect jobs" (in en). 2023-01-11. https://www.afr.com/policy/energy-and-climate/carbon-tariffs-backed-by-union-to-protect-jobs-20230111-p5cbvw.

- ↑ "OECD seeks global plan for carbon prices to avoid trade wars" (in en-CA). https://financialpost.com/commodities/energy/oecd-seeks-global-plan-for-carbon-prices-to-avoid-trade-wars.

- ↑ floors, Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva at the Brookings Institution Event: Building climate cooperation: The critical role for international carbon price. "Launch of IMF Staff Climate Note: A Proposal for an International Carbon Price Floor Among Large Emitters" (in en). https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2021/06/18/sp061821-launch-of-imf-staff-climate-note.

- ↑ "How and Why a Global Carbon Tax Could Revolutionize International Climate Change Law?" (in en). https://oxfordtax.sbs.ox.ac.uk/article/how-and-why-a-global-carbon-tax-could-revolutionize-international-climate-change-law.

- ↑ Carattini, Stefano; Kallbekken, Steffen; Orlov, Anton (January 2019). "How to win public support for a global carbon tax" (in en). Nature 565 (7739): 289–291. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-00124-x. PMID 30651626. Bibcode: 2019Natur.565..289C.

- ↑ Fabre, Adrien, The Global Climate Plan: A Global Plan to End Climate Change and Extreme Poverty (June 01, 2024). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4850808

- ↑ "Climate change: Shipping industry calls for new global carbon tax" (in en-GB). BBC News. 2021-04-21. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-56835352.

- ↑ Gerretsen, Isabelle (2022-05-23). "UN body makes 'breakthrough' on carbon price proposal for shipping" (in en). https://climatechangenews.com/2022/05/23/un-body-makes-breakthrough-on-carbon-price-proposal-for-shipping/.

- ↑ Harvey, Fiona (2023-06-26). "Shipping emissions could be halved without damaging trade, research finds" (in en-GB). The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/jun/26/shipping-emissions-could-be-halved-without-damaging-trade-research-finds.

- ↑ Harvey, Fiona (2023-03-22). "Pressure grows on shipping industry to accept carbon levy" (in en-GB). The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/mar/22/pressure-grows-on-shipping-industry-to-accept-carbon-levy.

- ↑ Harvey, Fiona (2022-09-19). "Vulnerable countries demand global tax to pay for climate-led loss and damage" (in en-GB). The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/sep/19/vulnerable-countries-demand-global-tax-to-pay-for-climate-led-loss-and-damage.

- ↑ Abnett, Kate (18 March 2024). "Pressure builds for charge on global shipping sector's CO2 emissions". Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/climate-energy/pressure-builds-charge-global-shipping-sectors-co2-emissions-2024-03-18/.

- ↑ c-fam. "A GLOBAL TAX IS A DIRECT THREAT TO THE UNBORN". https://c-fam.org/stop-un-global-tax/.

|

KSF

KSF