Four continents

From HandWiki - Reading time: 18 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 18 min

Europeans in the 16th century divided the world into four continents: Africa, America, Asia, and Europe.[1] Each of the four continents was seen to represent its quadrant of the world—Africa in the south, America in the west, Asia in the east, and Europe in the north. This division fit the Renaissance sensibilities of the time, which also divided the world into four seasons, four classical elements, four cardinal directions, four classical virtues, etc.

The four parts of the world[2] or the four corners of the world refers to Africa (the "south"), the Americas (the "west"), Asia (the "east"), and Europe (the "north").

Depictions of personifications of the four continents became popular in several media. Sets of four could be placed around all sorts of four-sided objects, or in pairs along the façade of a building with a central doorway. They were common subjects for prints, and later small porcelain figures. A set of loose conventions quickly arose as to the iconography of the figures. They were normally female, with Europe queenly and grandly dressed, Asia fully dressed but in an exotic style, with Africa and America at most half-dressed, and given exotic props as attributes.[3]

A three-cornered world

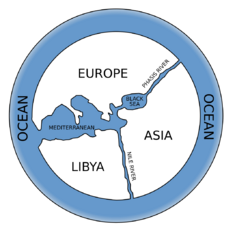

Before the discovery of the New World a commonplace of classical and medieval geography had been the "three parts" in which, from Mediterranean and European perspectives, the world was divided: Europe, Asia and Africa. As Laurent de Premierfait, the pre-eminent French translator of Latin literature in the early fifteenth century, informed his readers:

Asia is one of the three parts of the world, which the authors divide in Asia, Africa and Europe. Asia extends towards the Orient as far as the rising sun ("devers le souleil levant"), towards the south ("midi") it ends at the great sea, towards the occident it ends at our sea, and towards the north ("septentrion") it ends in the Maeotian marshes and the river named Thanaus.[4]

A fourth corner: the enlarged world

For Laurent's French readers, Asia ended at "our sea", the Mediterranean; Western Europeans were only dimly aware of the Ural Mountains, which divide Europe from Asia in the eyes of the modern geographer, and which represent the geological suture between two fragmentary continents, or cratons. Instead, the division between these continents in the European-centered picture was the Hellespont, which neatly separated Europe from Asia. From the European perspective, into the Age of Discovery, Asia began beyond the Hellespont with Asia Minor, where the Roman province of Asia had lain, and stretched away to what were initially unimaginably exotic and distant places— "the Orient".

Iconography

Cesare Ripa's Iconologia

In 1593, Cesare Ripa published one of the most successful emblem books for the use of artists and artisans who might be called upon to depict allegorical figures. He covered an astonishingly wide variety of fields, and his work was reprinted many times, though the text did not always correlate to the illustration.[5] The book was still being brought up-to-date in the 18th century. Ripa's text and the many sets of illustrations by various artists for different later editions (beginning in 1603) took some of the existing iconological conventions for the four continents, and were so influential that depictions for the next two centuries were largely determined by them.[3]

Europa is depicted as a woman dressed in fine clothes. She wears a crown while the papal tiara and crowns of kings lie at her feet, indicating her position of power over all the continents. The plentiful cornucopia shows Europe to be a land of abundance and the small temple she holds signifies Christianity. As a continent of great military force, Europe is also accompanied by a horse and an array of weapons.[6] This probably draws on the Europa regina map schematic.

Africa, by contrast wears the elephant headdress and is accompanied by animals common to Africa such as a lion, the scorpion of the desert sands, and Cleopatra's asps. These depictions come straight from Roman coins with personifications of the Roman province of Africa,[7] a much smaller strip of the Mediterranean coast. The abundance and fertility of Africa is symbolized in the cornucopia that she holds. Other personifications of Africa at the time depict her nude, symbolizing the Eurocentric perceptions of Africa as an uncivilized land. While the illustration of Africa in Ripa's Iconologia is light-skinned, it was also common to illustrate her with dark skin.[5]

Ripa's Asia, seen by Europe as a continent of exotic spices, silk, and the seat of Religion, wears rich clothing and carries a smoking censer. The continent's warm climate is represented by the wreath of flowers in her hair. A camel takes its ease beside her.[6]

The iconic image of America shows a Native American maiden in a feathered headdress, with bow and arrow. Perhaps she represents a fabled Amazon from the river that already carried the name. In other instances of American iconography, symbols meant to connote wilderness and a tropical climate occasionally included animals entirely absent from the Americas, such as the lion. Flora and fauna as images were often interchangeable between depictions of Africa and America during the seventeenth century due to the association of the tropical climate of Central and South America with that of Africa.[8]

In addition to having an untamed landscape, America was portrayed as a place of savagery by virtue of the people who inhabited it. This can be seen in the woodcut as America is depicted as much more warlike than the other three continents. As Claire Le Corbeiller explains, America “was usually envisioned as a rather fierce savage – only slightly removed in type from the medieval tradition of the wild man."[8]

The woodcut also shows America stepping on a human head, which is meant to connote cannibalism. Evidence of dismemberment, such as disembodied heads, in addition to America's bow and arrows and her lack of clothing were all meant to connote savagery.[9] Such imagery was not uncommon in depictions of the Americas, but it was not always the case. In time, the image of a wild native being justly subjugated by a European conqueror was turned into a portrayal of an “Indian princess”.[10]

Other depictions

The American millionaire philanthropist James Hazen Hyde, who inherited a majority share in Equitable Life Assurance Society, formed a collection of allegorical prints illustrating the Four Continents that are now at the New-York Historical Society; Hyde's drawings and a supporting collection of sets of porcelain table ornaments and other decorative arts illustrating the Four Continents were shared by various New York City museums.

The Renaissance associated one major river to each of the continents; Europe is represented by the Danube, Africa and Asia by the Nile and the Ganges respectively, and America is represented by the La Plata.[11] The Four Rivers theme appears for example in the Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi, a 17th-century fountain in Rome designed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini in the Piazza Navona in Rome, and in the painting The Four Continents by Peter Paul Rubens. Fountain of the Four Rivers, (Danube, Nile, Ganges, La Plata)

Decline

With the European discovery of the existence of Australia, the theme of the "Four Continents" lost much of its drive, long before another continent, Antarctica, was also discovered. The iconography survived as the Four Corners of the World, however, generally in self-consciously classicizing contexts: for instance, in New York, in front of the Beaux-Arts Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House (1907), four sculptural groups by Daniel Chester French symbolize the "Four Corners of the World".

Today

Continents have occasionally been grouped together by landmass.[12] The four resulting continental landmasses are, from largest to smallest: Afroeurasia, America, Antarctica and Australia.

See also

- Continent

- Four Corners (disambiguation)

- Four Seas

- Roof of the World

- Seven Seas

Notes

- ↑ Nothing was known of Australia, first sighted in the early seventeenth century, or Antarctica, first sighted in the nineteenth century.

- ↑ Ciappara, Frans (1998). "Society and inquisition in Malta 1743-1798". Durham University: Durhem E-Theses. p. 38. http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4672/1/4672_2141.PDF?UkUDh:CyT.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Hall, 129

- ↑ Asie est l'une des trois parties du monde que les auteurs divisent en Asie, Afrique et Europe. Asie se extend devers orient jusques a souleil levant, devers midi elle fine a la grant mer devers occident elle fine a notre mer, et devers septentrion elle fine aux paluz Meotides et au fleuve appellé Thanaus; Laurent de Premierfait's expanded translation of Boccaccio's De Casibus Virorum Illustrium (1409), quoted in Patricia M. Gathercole, "Laurent de Premierfait: The Translator of Boccaccio's De casibus virorum illustrium" The French Review 27.4 (February 1954:245-252) p. 249.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Maritz, J. A. (2002-01-01). "From Pompey to Plymouth: the personification of Africa in the art of Europe" (in en). Scholia: Studies in Classical Antiquity 11 (1): 65–79. ISSN 1018-9017. https://journals.co.za/content/scholia/11/1/EJC100201;jsessionid=7HjzrSO5-bUQeqRFrWLoI6Oc.sabinetlive.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Le Corbeiller, Clare (1961). "Miss America and Her Sisters: Personifications of the Four Parts of the World". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 19 (8): 209–223. doi:10.2307/3257853. ISSN 0026-1521.

- ↑ As coin of Hadrian, 136 AD, described as: "Africa, wearing elephant’s skin headdress, reclining left, holding scorpion and cornucopia, modius at her feet".

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Le Corbeiller, Claire (April 1961). "Miss America and Her Sisters: Personifications of the Four Parts of the World". https://www.metmuseum.org/pubs/bulletins/1/pdf/3257853.pdf.bannered.pdf.

- ↑ Morell, Vivienne (November 12, 2014). "The Four Parts of the World – Representations of the Continents". https://viviennemorrell.wordpress.com/2014/11/12/the-four-parts-of-the-world-representations-of-the-continents/.

- ↑ Higham, John (1990). "Indian Princess and Roman Goddess: The First Female Symbols of America". Proceedings of the America Antiquarian Society 100: 52.

- ↑ "Peter Paul Rubens". https://www.italian-renaissance-art.com/Rubens.html.

- ↑ R.W. McColl, ed (2005). "continents". Encyclopedia of World Geography. 1. Facts on File, Inc.. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-8160-7229-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=DJgnebGbAB8C&pg=PA215. Retrieved 26 June 2012. "And since Africa and Asia are connected at the Suez Peninsula, Europe, Africa, and Asia are sometimes combined as Afro-Eurasia or Eurafrasia. The International Olympic Committee's official flag, containing [...] the single continent of America (North and South America being connected as the Isthmus of Panama).".

References

- Hall, James, Hall's Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art, 1996 (2nd edn.), John Murray, ISBN 0719541476

- Honour, Hugh, The New Golden Land: European Images of America from the Discoveries to the Present Time. New York: Pantheon Books, 1975. An exhibition based on the book's premise was curated by Honour at the Cleveland Museum of Art, 1975–77.

- Le Corbeiller, Clare, "Miss America and Her Sisters, Personifications of the Four Parts of the World," Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Apr. 1961): 209–23.

- Fleming, E. McClung, "The American Image as Indian Princess, 1765-1783," Winterthur Portfolio 2 (1965): 65–81.

- Fleming, E. McClung, "From Indian Princess to Greek Goddess: The American Image, 1783-1815," Winterthur Portfolio 3 (1967): 37–66.

- Higham, John, "Indian Princess and Roman Goddess: The First Female Symbols of America," Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 100(1) 45-79: 1990

External links

- The Four Continents

- Hemisphere Maps

- The Universe Divided into Fours

- Guide to the James H. Hyde Collection of Allegorical Prints of the Four Continents

|

KSF

KSF