Geometric algebra

From HandWiki - Reading time: 43 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 43 min

In mathematics, a geometric algebra (also known as a real Clifford algebra) is an extension of elementary algebra to work with geometrical objects such as vectors. Geometric algebra is built out of two fundamental operations, addition and the geometric product. Multiplication of vectors results in higher-dimensional objects called multivectors. Compared to other formalisms for manipulating geometric objects, geometric algebra is noteworthy for supporting vector division and addition of objects of different dimensions.

The geometric product was first briefly mentioned by Hermann Grassmann,[1] who was chiefly interested in developing the closely related exterior algebra. In 1878, William Kingdon Clifford greatly expanded on Grassmann's work to form what are now usually called Clifford algebras in his honor (although Clifford himself chose to call them "geometric algebras"). Clifford defined the Clifford algebra and its product as a unification of the Grassmann algebra and Hamilton's quaternion algebra. Adding the dual of the Grassmann exterior product (the "meet") allows the use of the Grassmann–Cayley algebra, and a conformal version of the latter together with a conformal Clifford algebra yields a conformal geometric algebra (CGA) providing a framework for classical geometries.[2] In practice, these and several derived operations allow a correspondence of elements, subspaces and operations of the algebra with geometric interpretations. For several decades, geometric algebras went somewhat ignored, greatly eclipsed by the vector calculus then newly developed to describe electromagnetism. The term "geometric algebra" was repopularized in the 1960s by Hestenes, who advocated its importance to relativistic physics.[3]

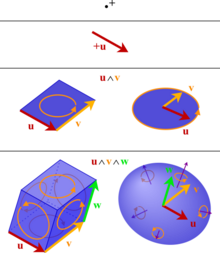

The scalars and vectors have their usual interpretation, and make up distinct subspaces of a geometric algebra. Bivectors provide a more natural representation of the pseudovector quantities of vector calculus, such as oriented area, oriented angle of rotation, torque, angular momentum and the electromagnetic field. A trivector can represent an oriented volume, and so on. An element called a blade may be used to represent a subspace of and orthogonal projections onto that subspace. Rotations and reflections are represented as elements. Unlike a vector algebra, a geometric algebra naturally accommodates any number of dimensions and any quadratic form such as in relativity.

Examples of geometric algebras applied in physics include the spacetime algebra (and the less common algebra of physical space) and the conformal geometric algebra. Geometric calculus, an extension of GA that incorporates differentiation and integration, can be used to formulate other theories such as complex analysis and differential geometry, e.g. by using the Clifford algebra instead of differential forms. Geometric algebra has been advocated, most notably by David Hestenes[4] and Chris Doran,[5] as the preferred mathematical framework for physics. Proponents claim that it provides compact and intuitive descriptions in many areas including classical and quantum mechanics, electromagnetic theory and relativity.[6] GA has also found use as a computational tool in computer graphics[7] and robotics.

Definition and notation

There are a number of different ways to define a geometric algebra. Hestenes's original approach was axiomatic,[8] "full of geometric significance" and equivalent to the universal Clifford algebra.[9] Given a finite-dimensional vector space over a field with a symmetric bilinear form (the inner product, e.g. the Euclidean or Lorentzian metric) , the geometric algebra of the quadratic space is the Clifford algebra which members are called multors or here multivectors. (The term multivector is often used more specificly for elements of exterior algebra.) As usual in this domain, for the remainder of this article, only the real case, , will be considered. The notation (respectively ) will be used to denote a geometric algebra for which the bilinear form has the signature (respectively ).

The essential product in the algebra is called the geometric product, and the product in the contained exterior algebra is called the exterior product (frequently called the wedge product and less often the outer product[lower-alpha 1]). It is standard to denote these respectively by juxtaposition (i.e., suppressing any explicit multiplication symbol) and the symbol . The above definition of the geometric algebra is abstract, so we summarize the properties of the geometric product by the following set of axioms. The geometric product has the following properties, for multors :

- (closure)

- , where is the identity element (existence of an identity element)

- (associativity)

- and (distributivity)

- , where is any element of the subspace of the algebra.

The exterior product has the same properties, except that the last property above is replaced by for .

Note that in the last property above, the real number need not be nonnegative if is not positive-definite. An important property of the geometric product is the existence of elements having a multiplicative inverse. For a vector , if then exists and is equal to . A nonzero element of the algebra does not necessarily have a multiplicative inverse. For example, if is a vector in such that , the element is both a nontrivial idempotent element and a nonzero zero divisor, and thus has no inverse.[lower-alpha 2]

It is usual to identify and with their images under the natural embeddings and . In this article, this identification is assumed. Throughout, the terms scalar and vector refer to elements of and respectively (and of their images under this embedding).

Geometric product

For vectors and , we may write the geometric product of any two vectors and as the sum of a symmetric product and an antisymmetric product:

Thus we can define the inner product[lower-alpha 3] of vectors as

so that the symmetric product can be written as

Conversely, is completely determined by the algebra. The antisymmetric part is the exterior product of the two vectors, the product of the contained exterior algebra:

Then by simple addition:

- the ungeneralized or vector form of the geometric product.

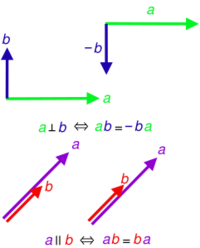

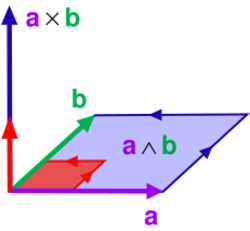

The inner and exterior products are associated with familiar concepts from standard vector algebra. Geometrically, and are parallel if their geometric product is equal to their inner product, whereas and are perpendicular if their geometric product is equal to their exterior product. In a geometric algebra for which the square of any nonzero vector is positive, the inner product of two vectors can be identified with the dot product of standard vector algebra. The exterior product of two vectors can be identified with the signed area enclosed by a parallelogram the sides of which are the vectors. The cross product of two vectors in dimensions with positive-definite quadratic form is closely related to their exterior product.

Most instances of geometric algebras of interest have a nondegenerate quadratic form. If the quadratic form is fully degenerate, the inner product of any two vectors is always zero, and the geometric algebra is then simply an exterior algebra. Unless otherwise stated, this article will treat only nondegenerate geometric algebras.

The exterior product is naturally extended as an associative bilinear binary operator between any two elements of the algebra, satisfying the identities

where the sum is over all permutations of the indices, with the sign of the permutation, and are vectors (not general elements of the algebra). Since every element of the algebra can be expressed as the sum of products of this form, this defines the exterior product for every pair of elements of the algebra. It follows from the definition that the exterior product forms an alternating algebra.

The equivalent structure equation for Clifford algebra is [13][14]

where is the Pfaffian of A and provides combinations, , of n indicies divided into 2i and n-2i parts and k is the parity of the combination.

The Pfaffian provides a metric for the exterior algebra and, as pointed out by Claude Chevalley, Clifford algebra reduces to the exterior algebra with a zero quadratic form.[15] The role the Pfaffian plays can be understood from a geometric viewpoint by developing Clifford algebra from simplices.[16] This derivation provides a better connection between Pascal's triangle and simplices because it provides an interpretation of the first column of ones.

Blades, grades, and canonical basis

A multivector that is the exterior product of linearly independent vectors is called a blade, and is said to be of grade .[lower-alpha 5] A multivector that is the sum of blades of grade is called a (homogeneous) multivector of grade . From the axioms, with closure, every multivector of the geometric algebra is a sum of blades.

Consider a set of linearly independent vectors spanning an -dimensional subspace of the vector space. With these, we can define a real symmetric matrix (in the same way as a Gramian matrix)

By the spectral theorem, can be diagonalized to diagonal matrix by an orthogonal matrix via

Define a new set of vectors , known as orthogonal basis vectors, to be those transformed by the orthogonal matrix:

Since orthogonal transformations preserve inner products, it follows that and thus the are perpendicular. In other words, the geometric product of two distinct vectors is completely specified by their exterior product, or more generally

Therefore, every blade of grade can be written as the exterior product of vectors. More generally, if a degenerate geometric algebra is allowed, then the orthogonal matrix is replaced by a block matrix that is orthogonal in the nondegenerate block, and the diagonal matrix has zero-valued entries along the degenerate dimensions. If the new vectors of the nondegenerate subspace are normalized according to

then these normalized vectors must square to or . By Sylvester's law of inertia, the total number of s and the total number of s along the diagonal matrix is invariant. By extension, the total number of these vectors that square to and the total number that square to is invariant. (The total number of basis vectors that square to zero is also invariant, and may be nonzero if the degenerate case is allowed.) We denote this algebra . For example, models three-dimensional Euclidean space, relativistic spacetime and a conformal geometric algebra of a three-dimensional space.

The set of all possible products of orthogonal basis vectors with indices in increasing order, including as the empty product, forms a basis for the entire geometric algebra (an analogue of the PBW theorem). For example, the following is a basis for the geometric algebra :

A basis formed this way is called a canonical basis for the geometric algebra, and any other orthogonal basis for will produce another canonical basis. Each canonical basis consists of elements. Every multivector of the geometric algebra can be expressed as a linear combination of the canonical basis elements. If the canonical basis elements are with being an index set, then the geometric product of any two multivectors is

The terminology "-vector" is often encountered to describe multivectors containing elements of only one grade. In higher dimensional space, some such multivectors are not blades (cannot be factored into the exterior product of vectors). By way of example, in cannot be factored; typically, however, such elements of the algebra do not yield to geometric interpretation as objects, although they may represent geometric quantities such as rotations. Only -, -, - and -vectors are always blades in -space.

Versor

A -versor is a multivector that can be expressed as the geometric product of invertible vectors.[lower-alpha 6][18] Unit quaternions (originally called versors by Hamilton) may be identified with rotors in 3D space in much the same way as real 2D rotors subsume complex numbers; for the details refer to Dorst.[19]

Some authors use the term "versor product" to refer to the frequently occurring case where an operand is "sandwiched" between operators. The descriptions for rotations and reflections, including their outermorphisms, are examples of such sandwiching. These outermorphisms have a particularly simple algebraic form.[lower-alpha 7] Specifically, a mapping of vectors of the form

- extends to the outermorphism

Since both operators and operand are versors there is potential for alternative examples such as rotating a rotor or reflecting a spinor always provided that some geometrical or physical significance can be attached to such operations.

By the Cartan–Dieudonné theorem we have that every isometry can be given as reflections in hyperplanes and since composed reflections provide rotations then we have that orthogonal transformations are versors.

In group terms, for a real, non-degenerate , having identified the group as the group of all invertible elements of , Lundholm gives a proof that the "versor group" (the set of invertible versors) is equal to the Lipschitz group (a.k.a. Clifford group, although Lundholm deprecates this usage).[20]

Subgroups of the Lipschitz group

Lundholm defines the , , and subgroups, generated by unit vectors, and in the case of and , only an even number of such vector factors can be present.[21]

| Subgroup | Definition | GA term |

|---|---|---|

| versors | ||

| unit versors | ||

| even unit versors | ||

| rotors |

Spinors are defined as elements of the even subalgebra of a real GA with spinor norm . Multiple analyses of spinors use GA as a representation.[22]

Grade projection

Using an orthogonal basis, a graded vector space structure can be established. Elements of the geometric algebra that are scalar multiples of are grade- blades and are called scalars. Multivectors that are in the span of are grade- blades and are the ordinary vectors. Multivectors in the span of are grade- blades and are the bivectors. This terminology continues through to the last grade of -vectors. Alternatively, grade- blades are called pseudoscalars, grade- blades pseudovectors, etc. Many of the elements of the algebra are not graded by this scheme since they are sums of elements of differing grade. Such elements are said to be of mixed grade. The grading of multivectors is independent of the basis chosen originally.

This is a grading as a vector space, but not as an algebra. Because the product of an -blade and an -blade is contained in the span of through -blades, the geometric algebra is a filtered algebra.

A multivector may be decomposed with the grade-projection operator , which outputs the grade- portion of . As a result:

As an example, the geometric product of two vectors since and and , for other than and .

The decomposition of a multivector may also be split into those components that are even and those that are odd:

This is the result of forgetting structure from a -graded vector space to -graded vector space. The geometric product respects this coarser grading. Thus in addition to being a -graded vector space, the geometric algebra is a -graded algebra or superalgebra.

Restricting to the even part, the product of two even elements is also even. This means that the even multivectors defines an even subalgebra. The even subalgebra of an -dimensional geometric algebra is isomorphic (without preserving either filtration or grading) to a full geometric algebra of dimensions. Examples include and .

Representation of subspaces

Geometric algebra represents subspaces of as blades, and so they coexist in the same algebra with vectors from . A -dimensional subspace of is represented by taking an orthogonal basis and using the geometric product to form the blade . There are multiple blades representing ; all those representing are scalar multiples of . These blades can be separated into two sets: positive multiples of and negative multiples of . The positive multiples of are said to have the same orientation as , and the negative multiples the opposite orientation.

Blades are important since geometric operations such as projections, rotations and reflections depend on the factorability via the exterior product that (the restricted class of) -blades provide but that (the generalized class of) grade- multivectors do not when .

Unit pseudoscalars

Unit pseudoscalars are blades that play important roles in GA. A unit pseudoscalar for a non-degenerate subspace of is a blade that is the product of the members of an orthonormal basis for . It can be shown that if and are both unit pseudoscalars for , then and . If one doesn't choose an orthonormal basis for , then the Plücker embedding gives a vector in the exterior algebra but only up to scaling. Using the vector space isomorphism between the geometric algebra and exterior algebra, this gives the equivalence class of for all . Orthonormality gets rid of this ambiguity except for the signs above.

Suppose the geometric algebra with the familiar positive definite inner product on is formed. Given a plane (two-dimensional subspace) of , one can find an orthonormal basis spanning the plane, and thus find a unit pseudoscalar representing this plane. The geometric product of any two vectors in the span of and lies in , that is, it is the sum of a -vector and a -vector.

By the properties of the geometric product, . The resemblance to the imaginary unit is not incidental: the subspace is -algebra isomorphic to the complex numbers. In this way, a copy of the complex numbers is embedded in the geometric algebra for each two-dimensional subspace of on which the quadratic form is definite.

It is sometimes possible to identify the presence of an imaginary unit in a physical equation. Such units arise from one of the many quantities in the real algebra that square to , and these have geometric significance because of the properties of the algebra and the interaction of its various subspaces.

In , a further familiar case occurs. Given a canonical basis consisting of orthonormal vectors of , the set of all -vectors is spanned by

Labelling these , and (momentarily deviating from our uppercase convention), the subspace generated by -vectors and -vectors is exactly . This set is seen to be the even subalgebra of , and furthermore is isomorphic as an -algebra to the quaternions, another important algebraic system.

Extensions of the inner and exterior products

It is common practice to extend the exterior product on vectors to the entire algebra. This may be done through the use of the above mentioned grade projection operator:

- (the exterior product)

This generalization is consistent with the above definition involving antisymmetrization. Another generalization related to the exterior product is the commutator product:

- (the commutator product)

The regressive product (usually referred to as the "meet") is the dual of the exterior product (or "join" in this context).[lower-alpha 8] The dual specification of elements permits, for blades and , the intersection (or meet) where the duality is to be taken relative to the smallest grade blade containing both and (the join).[24]

with the unit pseudoscalar of the algebra. The regressive product, like the exterior product, is associative.[25]

The inner product on vectors can also be generalized, but in more than one non-equivalent way. The paper (Dorst 2002) gives a full treatment of several different inner products developed for geometric algebras and their interrelationships, and the notation is taken from there. Many authors use the same symbol as for the inner product of vectors for their chosen extension (e.g. Hestenes and Perwass). No consistent notation has emerged.

Among these several different generalizations of the inner product on vectors are:

- (the left contraction)

- (the right contraction)

- (the scalar product)

- (the "(fat) dot" product)[lower-alpha 9]

(Dorst 2002) makes an argument for the use of contractions in preference to Hestenes's inner product; they are algebraically more regular and have cleaner geometric interpretations. A number of identities incorporating the contractions are valid without restriction of their inputs. For example,

Benefits of using the left contraction as an extension of the inner product on vectors include that the identity is extended to for any vector and multivector , and that the projection operation is extended to for any blade and any multivector (with a minor modification to accommodate null , given below).

Dual basis

Let be a basis of , i.e. a set of linearly independent vectors that span the -dimensional vector space . The basis that is dual to is the set of elements of the dual vector space that forms a biorthogonal system with this basis, thus being the elements denoted satisfying

where is the Kronecker delta.

Given a nondegenerate quadratic form on , becomes naturally identified with , and the dual basis may be regarded as elements of , but are not in general the same set as the original basis.

Given further a GA of , let

be the pseudoscalar (which does not necessarily square to ) formed from the basis . The dual basis vectors may be constructed as

where the denotes that the th basis vector is omitted from the product.

A dual basis is also known as a reciprocal basis or reciprocal frame.

A major usage of a dual basis is to separate vectors into components. Given a vector , scalar components can be defined as

in terms of which can be separated into vector components as

We can also define scalar components as

in terms of which can be separated into vector components in terms of the dual basis as

A dual basis as defined above for the vector subspace of a geometric algebra can be extended to cover the entire algebra.[26] For compactness, we'll use a single capital letter to represent an ordered set of vector indices. I.e., writing

where we can write a basis blade as

The corresponding reciprocal blade has the indices in opposite order:

Similar to the case above with vectors, it can be shown that

where is the scalar product.

With a multivector, we can define scalar components as[27]

in terms of which can be separated into component blades as

We can alternatively define scalar components

in terms of which can be separated into component blades as

Linear functions

Although a versor is easier to work with because it can be directly represented in the algebra as a multivector, versors are a subgroup of linear functions on multivectors, which can still be used when necessary. The geometric algebra of an -dimensional vector space is spanned by a basis of elements. If a multivector is represented by a real column matrix of coefficients of a basis of the algebra, then all linear transformations of the multivector can be expressed as the matrix multiplication by a real matrix. However, such a general linear transformation allows arbitrary exchanges among grades, such as a "rotation" of a scalar into a vector, which has no evident geometric interpretation.

A general linear transformation from vectors to vectors is of interest. With the natural restriction to preserving the induced exterior algebra, the outermorphism of the linear transformation is the unique[lower-alpha 10] extension of the versor. If is a linear function that maps vectors to vectors, then its outermorphism is the function that obeys the rule

for a blade, extended to the whole algebra through linearity.

Modeling geometries

Although a lot of attention has been placed on CGA, it is to be noted that GA is not just one algebra, it is one of a family of algebras with the same essential structure.[28]

Vector space model

The even subalgebra of is isomorphic to the complex numbers, as may be seen by writing a vector in terms of its components in an orthonormal basis and left multiplying by the basis vector , yielding

where we identify since

Similarly, the even subalgebra of with basis is isomorphic to the quaternions as may be seen by identifying , and .

Every associative algebra has a matrix representation; replacing the three Cartesian basis vectors by the Pauli matrices gives a representation of :

Dotting the "Pauli vector" (a dyad):

- with arbitrary vectors and and multiplying through gives:

- (Equivalently, by inspection, )

Spacetime model

In physics, the main applications are the geometric algebra of Minkowski 3+1 spacetime, , called spacetime algebra (STA),[3] or less commonly, , interpreted the algebra of physical space (APS).

While in STA, points of spacetime are represented simply by vectors, in APS, points of -dimensional spacetime are instead represented by paravectors, a three-dimensional vector (space) plus a one-dimensional scalar (time).

In spacetime algebra the electromagnetic field tensor has a bivector representation .[29] Here, the is the unit pseudoscalar (or four-dimensional volume element), is the unit vector in time direction, and and are the classic electric and magnetic field vectors (with a zero time component). Using the four-current , Maxwell's equations then become

Formulation Homogeneous equations Non-homogeneous equations Fields Potentials (any gauge) Potentials (Lorenz gauge)

In geometric calculus, juxtaposition of vectors such as in indicate the geometric product and can be decomposed into parts as . Here is the covector derivative in any spacetime and reduces to in flat spacetime. Where plays a role in Minkowski -spacetime which is synonymous to the role of in Euclidean -space and is related to the d'Alembertian by . Indeed, given an observer represented by a future pointing timelike vector we have

Boosts in this Lorentzian metric space have the same expression as rotation in Euclidean space, where is the bivector generated by the time and the space directions involved, whereas in the Euclidean case it is the bivector generated by the two space directions, strengthening the "analogy" to almost identity.

The Dirac matrices are a representation of , showing the equivalence with matrix representations used by physicists.

Homogeneous models

Homogeneous models generally refer to a projective representation in which the elements of the one-dimensional subspaces of a vector space represent points of a geometry.

In a geometric algebra of a space of dimensions, the rotors represent a set of transformations with degrees of freedom, corresponding to rotations – for example, when and when . Geometric algebra is often used to model a projective space, i.e. as a homogeneous model: a point, line, plane, etc. is represented by an equivalence class of elements of the algebra that differ by an invertible scalar factor.

The rotors in a space of dimension have degrees of freedom, the same as the number of degrees of freedom in the rotations and translations combined for an -dimensional space.

This is the case in Projective Geometric Algebra (PGA), which is used[30][31][32] to represent Euclidean isometries in Euclidean geometry (thereby covering the large majority of engineering applications of geometry). In this model, a degenerate dimension is added to the three Euclidean dimensions to form the algebra . With a suitable identification of subspaces to represent points, lines and planes, the versors of this algebra represent all proper Euclidean isometries, which are always screw motions in 3-dimensional space, along with all improper Euclidean isometries, which includes reflections, rotoreflections, transflections, and point reflections.

PGA combines with a dual operator to obtain meet, join, distance, and angle formulae. Depending on the author,[33][34] this could mean the Hodge star or the projective dual, though both result in identical equations being derived, albeit with different notation. In effect, the dual switches basis vectors that are present and absent in the expression of each term of the algebraic representation. For example, in the PGA or 3-dimensional space, the dual of the line is the line , because and are basis elements that are not contained in but are contained in . In the PGA of 2-dimensional space, the dual of is , since there is no element.

PGA is a widely used system that combines geometric algebra with homogeneous representations in geometry, but there exist several other such systems. The conformal model discussed below is homogeneous, as is "Conic Geometric Algebra",[35] and see Plane-based geometric algebra for discussion of homogeneous models of elliptic and hyperbolic geometry compared with the euclidean geometry derived from PGA.

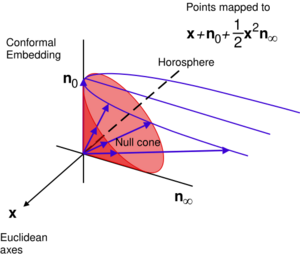

Conformal model

Working within GA, Euclidean space (along with a conformal point at infinity) is embedded projectively in the CGA via the identification of Euclidean points with 1D subspaces in the 4D null cone of the 5D CGA vector subspace. This allows all conformal transformations to be performed as rotations and reflections and is covariant, extending incidence relations of projective geometry to circles and spheres.

Specifically, we add orthogonal basis vectors and such that and to the basis of the vector space that generates and identify null vectors

- as a conformal point at infinity (see Compactification) and

- as the point at the origin, giving

This procedure has some similarities to the procedure for working with homogeneous coordinates in projective geometry and in this case allows the modeling of Euclidean transformations of as orthogonal transformations of a subset of .

A fast changing and fluid area of GA, CGA is also being investigated for applications to relativistic physics.

Table of models

Note in this list that and can be swapped and the same name applies; for example, with relatively little change occurring, see sign convention. For example, and are both referred to as Spacetime Algebra.[36]

| Signature | Names and acronyms | Blades, eg oriented geometric objects that algebra can represent | Rotors, eg orientation-preserving transformations that the algebra can represent | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vectorspace GA, VGA | Planes and lines through the origin | Rotations, eg | First GA to be discovered[by whom?] | |

| Plane-based GA, Projective GA, PGA | Planes, lines, and points anywhere in space | Rotations and translations, eg rigid motions, aka | Slight modifications to the signature allow for the modelling of hyperbolic and elliptic space, see main article. Cannot model the entire "projective" group. | |

| Spacetime Algebra, STA | Volumes, planes and lines through the origin in spacetime | Rotations and spacetime boosts, e.g. , the Lorentz group | Basis for Gauge Theory Gravity. | |

| Spacetime Algebra Projectivized,[37] STAP | Volumes, planes, lines, and points (events) in spacetime | Rotations, translations, and spacetime boosts (Poincare group) | ||

| Conformal GA, CGA | Spheres, circles, point pairs, lines, and planes anywhere in space | Transformations of space that preserve angles (Conformal group ) | ||

| Conformal Spacetime Algebra,[38] CSTA | Spheres, circles, planes, lines, light-cones, trajectories of objects with constant acceleration, all in spacetime | Conformal transformations of spacetime, e.g. transformations that preserve rapidity along arclengths through spacetime | Related to Twistor theory. | |

| Mother Algebra[39] | Unknown | Projective group | ||

| GA for Conics, GAC | Points, point pair/triple/quadruple, Conic, Pencil of up to 6 independent conics. | Reflections, translations, rotations, dilations, others | Conics can be created from control points and pencils of conics. | |

| Quadric Conformal GA, QCGA[42] | Points, tuples of up to 8 points, quadric surfaces, conics, conics on quadratic surfaces (such as Spherical conic), pencils of up to 9 quadric surfaces. | Reflections, translations, rotations, dilations, others | Quadric surfaces can be created from control points and their surface normals can be determined. | |

| Double Conformal Geometric Algebra (DCGA)[43] | Points, Darboux Cyclides, quadrics surfaces | Reflections, translations, rotations, dilations, others | Uses bivectors of two independent CGA basis to represents 5x5 symmetric "matrices" of 15 unique coefficients. This is at the cost of the ability to perform intersections and construction by points. |

Geometric interpretation of Vectorspace Geometric Algebra

Projection and rejection

For any vector and any invertible vector ,

where the projection of onto (or the parallel part) is

and the rejection of from (or the orthogonal part) is

Using the concept of a -blade as representing a subspace of and every multivector ultimately being expressed in terms of vectors, this generalizes to projection of a general multivector onto any invertible -blade as[lower-alpha 11]

with the rejection being defined as

The projection and rejection generalize to null blades by replacing the inverse with the pseudoinverse with respect to the contractive product.[lower-alpha 12] The outcome of the projection coincides in both cases for non-null blades.[44][45] For null blades , the definition of the projection given here with the first contraction rather than the second being onto the pseudoinverse should be used,[lower-alpha 13] as only then is the result necessarily in the subspace represented by .[44] The projection generalizes through linearity to general multivectors .[lower-alpha 14] The projection is not linear in and does not generalize to objects that are not blades.

Reflection

Simple reflections in a hyperplane are readily expressed in the algebra through conjugation with a single vector. These serve to generate the group of general rotoreflections and rotations.

The reflection of a vector along a vector , or equivalently in the hyperplane orthogonal to , is the same as negating the component of a vector parallel to . The result of the reflection will be

This is not the most general operation that may be regarded as a reflection when the dimension . A general reflection may be expressed as the composite of any odd number of single-axis reflections. Thus, a general reflection of a vector may be written

where

- and

If we define the reflection along a non-null vector of the product of vectors as the reflection of every vector in the product along the same vector, we get for any product of an odd number of vectors that, by way of example,

and for the product of an even number of vectors that

Using the concept of every multivector ultimately being expressed in terms of vectors, the reflection of a general multivector using any reflection versor may be written

where is the automorphism of reflection through the origin of the vector space () extended through linearity to the whole algebra.

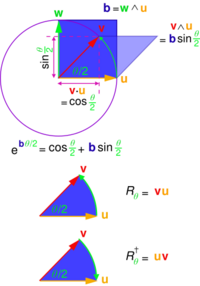

Rotations

If we have a product of vectors then we denote the reverse as

As an example, assume that we get

Scaling so that then

so leaves the length of unchanged. We can also show that

so the transformation preserves both length and angle. It therefore can be identified as a rotation or rotoreflection; is called a rotor if it is a proper rotation (as it is if it can be expressed as a product of an even number of vectors) and is an instance of what is known in GA as a versor.

There is a general method for rotating a vector involving the formation of a multivector of the form that produces a rotation in the plane and with the orientation defined by a -blade .

Rotors are a generalization of quaternions to -dimensional spaces.

Examples and applications

Hypervolume of a parallelotope spanned by vectors

For vectors and spanning a parallelogram we have

with the result that is linear in the product of the "altitude" and the "base" of the parallelogram, that is, its area.

Similar interpretations are true for any number of vectors spanning an -dimensional parallelotope; the exterior product of vectors , that is , has a magnitude equal to the volume of the -parallelotope. An -vector does not necessarily have a shape of a parallelotope – this is a convenient visualization. It could be any shape, although the volume equals that of the parallelotope.

Intersection of a line and a plane

We may define the line parametrically by where and are position vectors for points P and T and is the direction vector for the line.

Then

- and

so

and

Rotating systems

The mathematical description of rotational forces such as torque and angular momentum often makes use of the cross product of vector calculus in three dimensions with a convention of orientation (which defines handedness).

The cross product can be viewed in terms of the exterior product allowing a more natural geometric interpretation of the cross product as a bivector using the dual relationship

For example, torque is generally defined as the magnitude of the perpendicular force component times distance, or work per unit angle.

Suppose a circular path in an arbitrary plane containing orthonormal vectors and is parameterized by angle.

By designating the unit bivector of this plane as the imaginary number

this path vector can be conveniently written in complex exponential form

and the derivative with respect to angle is

So the torque, the rate of change of work , due to a force , is

Unlike the cross product description of torque, , the geometric algebra description does not introduce a vector in the normal direction; a vector that does not exist in two and that is not unique in greater than three dimensions. The unit bivector describes the plane and the orientation of the rotation, and the sense of the rotation is relative to the angle between the vectors and .

Geometric calculus

Geometric calculus extends the formalism to include differentiation and integration including differential geometry and differential forms.[46]

Essentially, the vector derivative is defined so that the GA version of Green's theorem is true,

and then one can write

as a geometric product, effectively generalizing Stokes' theorem (including the differential form version of it).

In when is a curve with endpoints and , then

reduces to

or the fundamental theorem of integral calculus.

Also developed are the concept of vector manifold and geometric integration theory (which generalizes differential forms).

History

Before the 20th century

Although the connection of geometry with algebra dates as far back at least to Euclid's Elements in the third century B.C. (see Greek geometric algebra), GA in the sense used in this article was not developed until 1844, when it was used in a systematic way to describe the geometrical properties and transformations of a space. In that year, Hermann Grassmann introduced the idea of a geometrical algebra in full generality as a certain calculus (analogous to the propositional calculus) that encoded all of the geometrical information of a space.[47] Grassmann's algebraic system could be applied to a number of different kinds of spaces, the chief among them being Euclidean space, affine space, and projective space. Following Grassmann, in 1878 William Kingdon Clifford examined Grassmann's algebraic system alongside the quaternions of William Rowan Hamilton in (Clifford 1878). From his point of view, the quaternions described certain transformations (which he called rotors), whereas Grassmann's algebra described certain properties (or Strecken such as length, area, and volume). His contribution was to define a new product — the geometric product – on an existing Grassmann algebra, which realized the quaternions as living within that algebra. Subsequently, Rudolf Lipschitz in 1886 generalized Clifford's interpretation of the quaternions and applied them to the geometry of rotations in dimensions. Later these developments would lead other 20th-century mathematicians to formalize and explore the properties of the Clifford algebra.

Nevertheless, another revolutionary development of the 19th-century would completely overshadow the geometric algebras: that of vector analysis, developed independently by Josiah Willard Gibbs and Oliver Heaviside. Vector analysis was motivated by James Clerk Maxwell's studies of electromagnetism, and specifically the need to express and manipulate conveniently certain differential equations. Vector analysis had a certain intuitive appeal compared to the rigors of the new algebras. Physicists and mathematicians alike readily adopted it as their geometrical toolkit of choice, particularly following the influential 1901 textbook Vector Analysis by Edwin Bidwell Wilson, following lectures of Gibbs.

In more detail, there have been three approaches to geometric algebra: quaternionic analysis, initiated by Hamilton in 1843 and geometrized as rotors by Clifford in 1878; geometric algebra, initiated by Grassmann in 1844; and vector analysis, developed out of quaternionic analysis in the late 19th century by Gibbs and Heaviside. The legacy of quaternionic analysis in vector analysis can be seen in the use of , , to indicate the basis vectors of : it is being thought of as the purely imaginary quaternions. From the perspective of geometric algebra, the even subalgebra of the Space Time Algebra is isomorphic to the GA of 3D Euclidean space and quaternions are isomorphic to the even subalgebra of the GA of 3D Euclidean space, which unifies the three approaches.

20th century and present

Progress on the study of Clifford algebras quietly advanced through the twentieth century, although largely due to the work of abstract algebraists such as Élie Cartan, Hermann Weyl and Claude Chevalley. The geometrical approach to geometric algebras has seen a number of 20th-century revivals. In mathematics, Emil Artin's Geometric Algebra[48] discusses the algebra associated with each of a number of geometries, including affine geometry, projective geometry, symplectic geometry, and orthogonal geometry. In physics, geometric algebras have been revived as a "new" way to do classical mechanics and electromagnetism, together with more advanced topics such as quantum mechanics and gauge theory.[5] David Hestenes reinterpreted the Pauli and Dirac matrices as vectors in ordinary space and spacetime, respectively, and has been a primary contemporary advocate for the use of geometric algebra.

In computer graphics and robotics, geometric algebras have been revived in order to efficiently represent rotations and other transformations. For applications of GA in robotics (screw theory, kinematics and dynamics using versors), computer vision, control and neural computing (geometric learning) see Bayro (2010).

See also

- Comparison of vector algebra and geometric algebra

- Clifford algebra

- Grassmann–Cayley algebra

- Spacetime algebra

- Spinor

- Quaternion

- Algebra of physical space

- Universal geometric algebra

Notes

- ↑ The term outer product used in geometric algebra conflicts with the meaning of outer product elsewhere in mathematics

- ↑ Given , we have that , showing that is idempotent, and that , showing that it is a nonzero zero divisor.

- ↑ This is a synonym for the scalar product of a pseudo-Euclidean vector space, and refers to the symmetric bilinear form on the -vector subspace, not the inner product on a normed vector space. Some authors may extend the meaning of inner product to the entire algebra, but there is little consensus on this. Even in texts on geometric algebras, the term is not universally used.

- ↑ When referring to grading under the geometric product, the literature generally only focuses on a -grading, meaning the split into even and odd -grades. is a subgroup of the full -grading of the geometric product.

- ↑ Grade is a synonym for degree of a homogeneous element under the grading as an algebra with the exterior product (a -grading), and not under the geometric product.[lower-alpha 4]

- ↑ "reviving and generalizing somewhat a term from hamilton's quaternion calculus which has fallen into disuse" Hestenes defined a -versor as a multivector which can be factored into a product of vectors.[17]

- ↑ Only the outermorphisms of linear transformations that respect the quadratic form fit this description; outermorphisms are not in general expressible in terms of the algebraic operations.

- ↑ [...] the outer product operation and the join relation have essentially the same meaning. The Grassmann–Cayley algebra regards the meet relation as its counterpart and gives a unifying framework in which these two operations have equal footing [...] Grassmann himself defined the meet operation as the dual of the outer product operation, but later mathematicians defined the meet operator independently of the outer product through a process called shuffle, and the meet operation is termed the shuffle product. It is shown that this is an antisymmetric operation that satisfies associativity, defining an algebra in its own right. Thus, the Grassmann–Cayley algebra has two algebraic structures simultaneously: one based on the outer product (or join), the other based on the shuffle product (or meet). Hence, the name "double algebra", and the two are shown to be dual to each other.[23]

- ↑ This should not be confused with Hestenes's irregular generalization , where the distinguishing notation is from Dorst, Fontijne & Mann (2007), p. 590, §B.1, which makes the point that scalar components must be handled separately with this product.

- ↑ The condition that is usually added to ensure that the zero map is unique.

- ↑ This definition follows Dorst, Fontijne & Mann (2007) and Perwass (2009) – the left contraction used by Dorst replaces the ("fat dot") inner product that Perwass uses, consistent with Perwass's constraint that grade of may not exceed that of .

- ↑ Dorst appears to merely assume such that , whereas Perwass (2009) defines , where is the conjugate of , equivalent to the reverse of up to a sign.

- ↑ That is to say, the projection must be defined as and not as , though the two are equivalent for non-null blades .

- ↑ This generalization to all is apparently not considered by Perwass or Dorst.

Citations

- ↑ Hestenes 1986, p. 6.

- ↑ Li 2008, p. 411.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Hestenes 1966.

- ↑ Hestenes 2003.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Doran 1994.

- ↑ Lasenby, Lasenby & Doran 2000.

- ↑ Hildenbrand et al. 2004.

- ↑ Hestenes & Sobczyk 1984, p. 3–5.

- ↑ Aragón, Aragón & Rodríguez 1997, p. 101.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Hestenes 2005.

- ↑ Penrose 2007.

- ↑ Wheeler, Misner & Thorne 1973, p. 83.

- ↑ Wilmot 1988a, p. 2338.

- ↑ Wilmot 1988b, p. 2346.

- ↑ Chevalley 1991.

- ↑ Wilmot 2023.

- ↑ Hestenes & Sobczyk 1984, p. 103.

- ↑ Dorst, Fontijne & Mann 2007, p. 204.

- ↑ Dorst, Fontijne & Mann 2007, pp. 177–182.

- ↑ Lundholm & Svensson 2009, pp. 58 et seq.

- ↑ Lundholm & Svensson 2009, p. 58.

- ↑ Francis & Kosowsky 2008.

- ↑ Kanatani 2015, pp. 112–113.

- ↑ Dorst & Lasenby 2011, p. 443.

- ↑ Vaz & da Rocha 2016, §2.8.

- ↑ Hestenes & Sobczyk 1984, p. 31.

- ↑ Doran & Lasenby 2003, p. 102.

- ↑ Dorst & Lasenby 2011, p. vi.

- ↑ "Electromagnetism using Geometric Algebra versus Components". http://www.av8n.com/physics/maxwell-ga.htm.

- ↑ Selig 2005.

- ↑ Hadfield & Lasenby 2020.

- ↑ "Projective Geometric Algebra". https://projectivegeometricalgebra.org/.

- ↑ Selig 2000.

- ↑ Lengyel 2016.

- ↑ Hrdina, Návrat & Vašík 2018. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFHrdinaNávratVašík2018 (help)

- ↑ https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-022-06895-0

- ↑ Sokolov, A. (2013-07-16). "Clifford algebra and the projective model of Minkowski (pseudo-Euclidean) spaces". arXiv: Metric Geometry.

- ↑ Lasenby, Anthony (2004). "Conformal Models of de Sitter Space, Initial Conditions for Inflation and the CMB". AIP Conference Proceedings (AIP) 736: 53–70. doi:10.1063/1.1835174. Bibcode: 2004AIPC..736...53L. http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.1835174.

- ↑ Dorst 2016.

- ↑ (in en) Geometric Algebra with Applications in Engineering. Geometry and Computing. 4. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 2009. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-89068-3. ISBN 978-3-540-89067-6. Bibcode: 2009gaae.book.....P. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-540-89068-3.

- ↑ Hrdina, Jaroslav; Návrat, Aleš; Vašík, Petr (July 2018). "Geometric Algebra for Conics" (in en). Advances in Applied Clifford Algebras 28 (3). doi:10.1007/s00006-018-0879-2. ISSN 0188-7009. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00006-018-0879-2.

- ↑ Breuils, Stéphane; Fuchs, Laurent; Hitzer, Eckhard; Nozick, Vincent; Sugimoto, Akihiro (July 2019). "Three-dimensional quadrics in extended conformal geometric algebras of higher dimensions from control points, implicit equations and axis alignment" (in en). Advances in Applied Clifford Algebras 29 (3). doi:10.1007/s00006-019-0974-z. ISSN 0188-7009. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00006-019-0974-z.

- ↑ Easter, Robert Benjamin; Hitzer, Eckhard (September 2017). "Double Conformal Geometric Algebra" (in en). Advances in Applied Clifford Algebras 27 (3): 2175–2199. doi:10.1007/s00006-017-0784-0. ISSN 0188-7009. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00006-017-0784-0.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Dorst, Fontijne & Mann 2007, §3.6 p. 85.

- ↑ Perwass 2009, §3.2.10.2 p. 83.

- ↑ Hestenes & Sobczyk 1984.

- ↑ Grassmann 1844.

- ↑ Artin 1988.

References and further reading

- Arranged chronologically

- Grassmann, Hermann (1844), Die lineale Ausdehnungslehre ein neuer Zweig der Mathematik: dargestellt und durch Anwendungen auf die übrigen Zweige der Mathematik, wie auch auf die Statik, Mechanik, die Lehre vom Magnetismus und die Krystallonomie erläutert, Leipzig: O. Wigand, OCLC 20521674, https://books.google.com/books?id=bKgAAAAAMAAJ

- Clifford, Professor (1878). "Applications of Grassmann's Extensive Algebra". American Journal of Mathematics 1 (4): 350–358. doi:10.2307/2369379.

- Artin, Emil (1988), Geometric algebra, Wiley Classics Library, Wiley, doi:10.1002/9781118164518, ISBN 978-0-471-60839-4

- Hestenes, David (1966), Space–time Algebra, Gordon and Breach, ISBN 978-0-677-01390-9, OCLC 996371

- Wheeler, J. A.; Misner, C.; Thorne, K. S. (1973), Gravitation, W.H. Freeman, ISBN 978-0-7167-0344-0

- Bourbaki, Nicolas (1980), "Ch. 9 "Algèbres de Clifford"", Eléments de Mathématique. Algèbre, Hermann, ISBN 9782225655166

- Hestenes, David; Sobczyk, Garret (1984). Clifford Algebra to Geometric Calculus, a Unified Language for Mathematics and Physics. Springer Netherlands. ISBN 9789027716736.

- Hestenes, David (1986), "A Unified Language for Mathematics and Physics", in J.S.R. Chisholm; A.K. Commons, Clifford Algebras and Their Applications in Mathematical Physics, NATO ASI Series (Series C), 183, Springer, pp. 1–23, doi:10.1007/978-94-009-4728-3_1, ISBN 978-94-009-4728-3

- Wilmot, G.P. (1988a), The Structure of Clifford algebra. Journal of Mathematical Physics, 29, pp. 2338–2345

- Wilmot, G.P. (1988b), "Clifford algebra and the Pfaffian expansion", Journal of Mathematical Physics 29: 2346–2350, doi:10.1063/1.528118

- Chevalley, Claude (1991), The Algebraic Theory of Spinors and Clifford Algebras, Collected Works, 2, Springer, ISBN 3-540-57063-2

- Doran, Chris J. L. (1994), Geometric Algebra and its Application to Mathematical Physics, University of Cambridge, doi:10.17863/CAM.16148, OCLC 53604228

- Baylis, W. E., ed. (2011), Clifford (Geometric) Algebra with Applications to Physics, Mathematics, and Engineering, Birkhäuser, ISBN 9781461241058

- Aragón, G.; Aragón, J.L.; Rodríguez, M.A. (1997), "Clifford Algebras and Geometric Algebra", Advances in Applied Clifford Algebras 7 (2): 91–102, doi:10.1007/BF03041220

- Hestenes, David (1999), New Foundations for Classical Mechanics (2nd ed.), Springer Verlag, ISBN 978-0-7923-5302-7

- Lasenby, Joan; Lasenby, Anthony N.; Doran, Chris J. L. (2000), "A Unified Mathematical Language for Physics and Engineering in the 21st Century", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 358 (1765): 21–39, doi:10.1098/rsta.2000.0517, Bibcode: 2000RSPTA.358...21L, http://geometry.mrao.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/00RSocMillen.pdf

- Baylis, W. E. (2002), Electrodynamics: A Modern Geometric Approach (2nd ed.), Birkhäuser, ISBN 978-0-8176-4025-5

- Dorst, Leo (2002), "The Inner Products of Geometric Algebra", in Dorst, L.; Doran, C.; Lasenby, J., Applications of Geometric Algebra in Computer Science and Engineering, Birkhäuser, pp. 35–46, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-0089-5_2, ISBN 978-1-4612-0089-5

- Doran, Chris J. L.; Lasenby, Anthony N. (2003), Geometric Algebra for Physicists, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-71595-9, http://assets.cambridge.org/052148/0221/sample/0521480221WS.pdf

- Hestenes, David (2003), "Oersted Medal Lecture 2002: Reforming the Mathematical Language of Physics", Am. J. Phys. 71 (2): 104–121, doi:10.1119/1.1522700, Bibcode: 2003AmJPh..71..104H, http://geocalc.clas.asu.edu/pdf/OerstedMedalLecture.pdf

- Hildenbrand, Dietmar; Fontijne, Daniel; Perwass, Christian; Dorst, Leo (2004), "Geometric Algebra and its Application to Computer Graphics", Proceedings of Eurographics 2004, doi:10.2312/egt.20041032, http://www.gaalop.de/dhilden_data/CLUScripts/eg04_tut03.pdf

- Hestenes, David (2005), Introduction to Primer for Geometric Algebra, http://geocalc.clas.asu.edu/html/IntroPrimerGeometricAlgebra.html

- Selig, J.M. (2005) (in en). Geometric Fundamentals of Robotics. Monographs in Computer Science. New York, NY: Springer New York. doi:10.1007/b138859. ISBN 978-0-387-20874-9. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/b138859.

- Bain, J. (2006), Dennis Dieks, ed., The ontology of spacetime, Elsevier, p. 54 ff, ISBN 978-0-444-52768-4, https://books.google.com/books?id=OI5BySlm-IcC&pg=PT72

- Dorst, Leo; Fontijne, Daniel; Mann, Stephen (2007), Geometric algebra for computer science: an object-oriented approach to geometry, Elsevier, ISBN 978-0-12-369465-2, OCLC 132691969, http://www.geometricalgebra.net/

- Penrose, Roger (2007), The Road to Reality, Vintage books, ISBN 978-0-679-77631-4

- Francis, Matthew R.; Kosowsky, Arthur (2008), "The Construction of Spinors in Geometric Algebra", Annals of Physics 317 (2): 383–409, doi:10.1016/j.aop.2004.11.008, Bibcode: 2005AnPhy.317..383F

- Li, Hongbo (2008), Invariant Algebras and Geometric Reasoning, World Scientific, ISBN 9789812770110, https://books.google.com/books?id=bUEcbyfW55YC. Chapter 1 as PDF

- Vince, John A. (2008), Geometric Algebra for Computer Graphics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-84628-996-5

- Lundholm, Douglas; Svensson, Lars (2009), "Clifford Algebra, Geometric Algebra and Applications", arXiv:0907.5356v1 [math-ph]

- Perwass, Christian (2009), Geometric Algebra with Applications in Engineering, Geometry and Computing, 4, Springer Science & Business Media, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-89068-3, ISBN 978-3-540-89068-3, Bibcode: 2009gaae.book.....P

- Selig, J.M. (2000). "Clifford algebra of points, lines and planes" (in en). Robotica 18 (5): 545–556. doi:10.1017/S0263574799002568. ISSN 0263-5747. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S0263574799002568/type/journal_article.

- Bayro-Corrochano, Eduardo (2010), Geometric Computing for Wavelet Transforms, Robot Vision, Learning, Control and Action, Springer Verlag, ISBN 9781848829299

- Bayro-Corrochano, E., ed. (2010), Geometric Algebra Computing in Engineering and Computer Science, Springer, ISBN 9781849961080, https://books.google.com/books?id=MaVDAAAAQBAJ Extract online at http://geocalc.clas.asu.edu/html/UAFCG.html #5 New Tools for Computational Geometry and rejuvenation of Screw Theory

- Goldman, Ron (2010), Rethinking Quaternions: Theory and Computation, Morgan & Claypool, Part III. Rethinking Quaternions and Clifford Algebras, ISBN 978-1-60845-420-4

- Dorst, Leo.; Lasenby, Joan (2011), Guide to Geometric Algebra in Practice, Springer, ISBN 9780857298119

- Macdonald, Alan (2011), Linear and Geometric Algebra, CreateSpace, ISBN 9781453854938, OCLC 704377582, http://faculty.luther.edu/~macdonal/laga/

- Snygg, John (2011), A New Approach to Differential Geometry using Clifford's Geometric Algebra, Springer, ISBN 978-0-8176-8282-8

- Hildenbrand, Dietmar (2012), "Foundations of Geometric Algebra computing", Numerical Analysis and Applied Mathematics Icnaam 2012: International Conference of Numerical Analysis and Applied Mathematics, AIP Conference Proceedings 1479 (1): 27–30, doi:10.1063/1.4756054, ISBN 978-3-642-31793-4, Bibcode: 2012AIPC.1479...27H

- Bromborsky, Alan (2014), An introduction to Geometric Algebra and Calculus, http://mathschoolinternational.com/Math-Books/Books-Geometric-Algebra/Books/An-Introduction-to-Geometric-Algebra-and-Calculus-by-Alan-Bromborsky.pdf

- Klawitter, Daniel (2014), Clifford Algebras: Geometric Modelling and Chain Geometries with Application in Kinematics, Springer, ISBN 9783658076184

- Kanatani, Kenichi (2015), Understanding Geometric Algebra: Hamilton, Grassmann, and Clifford for Computer Vision and Graphics, CRC Press, ISBN 9781482259513

- Li, Hongbo; Huang, Lei; Shao, Changpeng; Dong, Lei (2015), "Three-Dimensional Projective Geometry with Geometric Algebra", arXiv:1507.06634v1 [math.MG]

- Hestenes, David (2016). "The Genesis of Geometric Algebra:A Personal Retrospective". Advances in Applied Clifford Algebras 27 (1): 351–379. doi:10.1007/s00006-016-0664-z.

- Dorst, Leo (2016), 3D Oriented Projective Geometry Through Versors of , Springer, ISBN 9783658076184

- Lengyel, Eric (2016). Foundations of game engine development. Mathematics. 1. Lincoln, California: Terathon Software LLC. ISBN 978-0-9858117-4-7.

- Vaz, Jayme; da Rocha, Roldão (2016), An Introduction to Clifford Algebras and Spinors, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-878292-6, Bibcode: 2016icas.book.....V

- Du, Juan; Goldman, Ron; Mann, Stephen (2017). "Modeling 3D Geometry in the Clifford Algebra R(4,4)". Advances in Applied Clifford Algebras 27 (4): 3039–3062. doi:10.1007/s00006-017-0798-7.

- Bayro-Corrochano, Eduardo (2018). Computer Vision, Graphics and Neurocomputing. Geometric Algebra Applications. I. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-74830-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=SSVhDwAAQBAJ.

- Breuils, Stéphane (2018). Structure algorithmique pour les opérateurs d'Algèbres Géométriques et application aux surfaces quadriques (PDF) (PHD). université-paris-est. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-07-14.

- Lavor, Carlile; Xambó-Descamps, Sebastià; Zaplana, Isiah (2018). A Geometric Algebra Invitation to Space-Time Physics, Robotics and Molecular Geometry. Springer. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-3-319-90665-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=avBjDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA117.

- Hrdina, Jaroslav; Návrat, Aleš; Vašík, Petr (2018). "Geometric Algebra for Conics" (in en). Advances in Applied Clifford Algebras 28 (3): 66. doi:10.1007/s00006-018-0879-2. ISSN 1661-4909. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00006-018-0879-2.

- Josipović, Miroslav (2019). Geometric Multiplication of Vectors: An Introduction to Geometric Algebra in Physics. Springer International Publishing;Birkhäuser. pp. 256. ISBN 978-3-030-01756-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=4uG_DwAAQBAJ.

- Hadfield, Hugo; Lasenby, Joan (2020), "Constrained Dynamics in Conformal and Projective Geometric Algebra", Advances in Computer Graphics, Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Cham: Springer International Publishing) 12221: pp. 459–471, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-61864-3_39, ISBN 978-3-030-61863-6, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-61864-3_39, retrieved 2023-10-03

- Wilmot, G.P. (2023). "The Algebra Of Geometry". https://github.com/GPWilmot/geoalg.

External links

- A Survey of Geometric Algebra and Geometric Calculus Alan Macdonald, Luther College, Iowa.

- Imaginary Numbers are not Real – the Geometric Algebra of Spacetime. Introduction (Cambridge GA group).

- Geometric Algebra 2015, Masters Course in Scientific Computing, from Dr. Chris Doran (Cambridge).

- Maths for (Games) Programmers: 5 – Multivector methods. Comprehensive introduction and reference for programmers, from Ian Bell.

- IMPA Summer School 2010 Fernandes Oliveira Intro and Slides.

- University of Fukui E.S.M. Hitzer and Japan GA publications.

- Google Group for GA

- Geometric Algebra Primer Introduction to GA, Jaap Suter.

- Geometric Algebra Resources curated wiki, Pablo Bleyer.

- Applied Geometric Algebras in Computer Science and Engineering 2018 Early Proceedings

- GAME2020 Geometric Algebra Mini Event

- AGACSE 2021 Videos

English translations of early books and papers

- G. Combebiac, "calculus of tri-quaternions" (Doctoral dissertation)

- M. Markic, "Transformants: A new mathematical vehicle. A synthesis of Combebiac's tri-quaternions and Grassmann's geometric system. The calculus of quadri-quaternions"

- C. Burali-Forti, "The Grassmann method in projective geometry" A compilation of three notes on the application of exterior algebra to projective geometry

- C. Burali-Forti, "Introduction to Differential Geometry, following the method of H. Grassmann" Early book on the application of Grassmann algebra

- H. Grassmann, "Mechanics, according to the principles of the theory of extension" One of his papers on the applications of exterior algebra.

Research groups

- Geometric Calculus International. Links to Research groups, Software, and Conferences, worldwide.

- Cambridge Geometric Algebra group. Full-text online publications, and other material.

- University of Amsterdam group

- Geometric Calculus research & development (Arizona State University).

- GA-Net blog and newsletter archive. Geometric Algebra/Clifford Algebra development news.

- Geometric Algebra for Perception Action Systems. Geometric Cybernetics Group (CINVESTAV, Campus Guadalajara, Mexico).

|

KSF

KSF