Geometric progression

From HandWiki - Reading time: 8 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 8 min

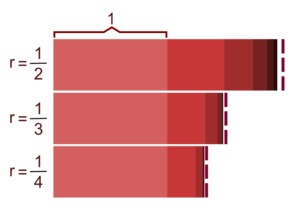

In mathematics, a geometric progression, also known as a geometric sequence, is a sequence of non-zero numbers where each term after the first is found by multiplying the previous one by a fixed, non-zero number called the common ratio. For example, the sequence 2, 6, 18, 54, ... is a geometric progression with common ratio 3. Similarly 10, 5, 2.5, 1.25, ... is a geometric sequence with common ratio 1/2.

Examples of a geometric sequence are powers rk of a fixed non-zero number r, such as 2k and 3k. The general form of a geometric sequence is

where r ≠ 0 is the common ratio and a ≠ 0 is a scale factor, equal to the sequence's start value. The sum of a geometric progression's terms is called a geometric series.

Elementary properties

The n-th term of a geometric sequence with initial value a = a1 and common ratio r is given by

and in general

Such a geometric sequence also follows the recursive relation

- for every integer

Generally, to check whether a given sequence is geometric, one simply checks whether successive entries in the sequence all have the same ratio.

The common ratio of a geometric sequence may be negative, resulting in an alternating sequence, with numbers alternating between positive and negative. For instance

- 1, −3, 9, −27, 81, −243, ...

is a geometric sequence with common ratio −3.

The behaviour of a geometric sequence depends on the value of the common ratio. If the common ratio is:

- positive, the terms will all be the same sign as the initial term.

- negative, the terms will alternate between positive and negative.

- greater than 1, there will be exponential growth towards positive or negative infinity (depending on the sign of the initial term).

- 1, the progression is a constant sequence.

- between −1 and 1 but not zero, there will be exponential decay towards zero (→ 0).

- −1, the absolute value of each term in the sequence is constant and terms alternate in sign.

- less than −1, for the absolute values there is exponential growth towards (unsigned) infinity, due to the alternating sign.

Geometric sequences (with common ratio not equal to −1, 1 or 0) show exponential growth or exponential decay, as opposed to the linear growth (or decline) of an arithmetic progression such as 4, 15, 26, 37, 48, … (with common difference 11). This result was taken by T.R. Malthus as the mathematical foundation of his Principle of Population. Note that the two kinds of progression are related: exponentiating each term of an arithmetic progression yields a geometric progression, while taking the logarithm of each term in a geometric progression with a positive common ratio yields an arithmetic progression.

An interesting result of the definition of the geometric progression is that any three consecutive terms a, b and c will satisfy the following equation:

where b is considered to be the geometric mean between a and c.

Geometric series

In mathematics, a geometric series is the sum of an infinite number of terms that have a constant ratio between successive terms. For example, the series

is geometric, because each successive term can be obtained by multiplying the previous term by . In general, a geometric series is written as , where is the coefficient of each term and is the common ratio between adjacent terms. The geometric series had an important role in the early development of calculus, is used throughout mathematics, and can serve as an introduction to frequently used mathematical tools such as the Taylor series, the Fourier series, and the matrix exponential.

The name geometric series indicates each term is the geometric mean of its two neighboring terms, similar to how the name arithmetic series indicates each term is the arithmetic mean of its two neighboring terms.Product

The product of a geometric progression is the product of all terms. It can be quickly computed by taking the geometric mean of the progression's first and last individual terms, and raising that mean to the power given by the number of terms. (This is very similar to the formula for the sum of terms of an arithmetic sequence: take the arithmetic mean of the first and last individual terms, and multiply by the number of terms.)

As the geometric mean of two numbers equals the square root of their product, the product of a geometric progression is:

- .

(An interesting aspect of this formula is that, even though it involves taking the square root of a potentially-odd power of a potentially-negative r, it cannot produce a complex result if neither a nor r has an imaginary part. It is possible, should r be negative and n be odd, for the square root to be taken of a negative intermediate result, causing a subsequent intermediate result to be an imaginary number. However, an imaginary intermediate formed in that way will soon afterwards be raised to the power of , which must be an even number because n by itself was odd; thus, the final result of the calculation may plausibly be an odd number, but it could never be an imaginary one.)

Proof

Let P represent the product. By definition, one calculates it by explicitly multiplying each individual term together. Written out in full,

- .

Carrying out the multiplications and gathering like terms,

- .

The exponent of r is the sum of an arithmetic sequence. Substituting the formula for that calculation,

- ,

which enables simplifying the expression to

- .

Rewriting a as ,

- ,

which concludes the proof.

History

A clay tablet from the Early Dynastic Period in Mesopotamia, MS 3047, contains a geometric progression with base 3 and multiplier 1/2. It has been suggested to be Sumerian, from the city of Shuruppak. It is the only known record of a geometric progression from before the time of Babylonian mathematics.[1]

Books VIII and IX of Euclid's Elements analyzes geometric progressions (such as the powers of two, see the article for details) and give several of their properties.[2]

See also

- Arithmetic progression – Sequence of equally spaced numbers

- Arithmetico-geometric sequence – Mathematical sequence satisfying a specific pattern

- Linear difference equation

- Exponential function – Mathematical function, denoted exp(x) or e^x

- Harmonic progression – Progression formed by taking the reciprocals of an arithmetic progression

- Harmonic series – Divergent sum of all positive unit fractions

- Infinite series – Infinite sum

- Preferred number – Standard guidelines for choosing exact product dimensions within a given set of constraints

- Geometric distribution – Probability distribution

References

- ↑ Friberg, Jöran (2007). "MS 3047: An Old Sumerian Metro-Mathematical Table Text". in Friberg, Jöran. A remarkable collection of Babylonian mathematical texts. Sources and Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences. New York: Springer. pp. 150–153. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-48977-3. ISBN 978-0-387-34543-7.

- ↑ Heath, Thomas L. (1956). The Thirteen Books of Euclid's Elements (2nd ed. [Facsimile. Original publication: Cambridge University Press, 1925] ed.). New York: Dover Publications. https://archive.org/details/thirteenbooksofe00eucl.

- Hall & Knight, Higher Algebra, p. 39, ISBN 81-8116-000-2

External links

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Geometric progression", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=p/g044290

- Derivation of formulas for sum of finite and infinite geometric progression at Mathalino.com

- Geometric Progression Calculator

- Nice Proof of a Geometric Progression Sum at sputsoft.com

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "Geometric Series". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/GeometricSeries.html.

|

KSF

KSF