Group action

From HandWiki - Reading time: 21 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 21 min

| Algebraic structure → Group theory Group theory |

|---|

|

In mathematics, a group action of a group on a set is a group homomorphism from to some group (under function composition) of functions from to itself. It is said that acts on .

Many sets of transformations form a group under function composition; for example, the rotations around a point in the plane. It is often useful to consider the group as an abstract group, and to say that one has a group action of the abstract group that consists of performing the transformations of the group of transformations. The reason for distinguishing the group from the transformations is that, generally, a group of transformations of a structure acts also on various related structures; for example, the above rotation group also acts on triangles by transforming triangles into triangles.

If a group acts on a structure, it will usually also act on objects built from that structure. For example, the group of Euclidean isometries acts on Euclidean space and also on the figures drawn in it; in particular, it acts on the set of all triangles. Similarly, the group of symmetries of a polyhedron acts on the vertices, the edges, and the faces of the polyhedron.

A group action on a vector space is called a representation of the group. In the case of a finite-dimensional vector space, it allows one to identify many groups with subgroups of the general linear group , the group of the invertible matrices of dimension over a field .

The symmetric group acts on any set with elements by permuting the elements of the set. Although the group of all permutations of a set depends formally on the set, the concept of group action allows one to consider a single group for studying the permutations of all sets with the same cardinality.

Definition

Left group action

If is a group with identity element , and is a set, then a (left) group action of on X is a function

that satisfies the following two axioms:[1]

Identity: Compatibility:

for all g and h in G and all x in .

The group is then said to act on (from the left). A set together with an action of is called a (left) -set.

It can be notationally convenient to curry the action , so that, instead, one has a collection of transformations αg : X → X, with one transformation αg for each group element g ∈ G. The identity and compatibility relations then read

and

The second axiom states that the function composition is compatible with the group multiplication; they form a commutative diagram. This axiom can be shortened even further, and written as .

With the above understanding, it is very common to avoid writing entirely, and to replace it with either a dot, or with nothing at all. Thus, α(g, x) can be shortened to g⋅x or gx, especially when the action is clear from context. The axioms are then

From these two axioms, it follows that for any fixed g in , the function from X to itself which maps x to g⋅x is a bijection, with inverse bijection the corresponding map for g−1. Therefore, one may equivalently define a group action of G on X as a group homomorphism from G into the symmetric group Sym(X) of all bijections from X to itself.[2]

Right group action

Likewise, a right group action of on is a function

that satisfies the analogous axioms:[3]

Identity: Compatibility:

(with α(x, g) often shortened to xg or x⋅g when the action being considered is clear from context)

Identity: Compatibility:

for all g and h in G and all x in X.

The difference between left and right actions is in the order in which a product gh acts on x. For a left action, h acts first, followed by g second. For a right action, g acts first, followed by h second. Because of the formula (gh)−1 = h−1g−1, a left action can be constructed from a right action by composing with the inverse operation of the group. Also, a right action of a group G on X can be considered as a left action of its opposite group Gop on X.

Thus, for establishing general properties of group actions, it suffices to consider only left actions. However, there are cases where this is not possible. For example, the multiplication of a group induces both a left action and a right action on the group itself—multiplication on the left and on the right, respectively.

Notable properties of actions

Let G be a group acting on a set X. The action is called faithful or effective if g⋅x = x for all x ∈ X implies that g = eG. Equivalently, the homomorphism from G to the group of bijections of X corresponding to the action is injective.

The action is called free (or semiregular or fixed-point free) if the statement that g⋅x = x for some x ∈ X already implies that g = eG. In other words, no non-trivial element of G fixes a point of X. This is a much stronger property than faithfulness.

For example, the action of any group on itself by left multiplication is free. This observation implies Cayley's theorem that any group can be embedded in a symmetric group (which is infinite when the group is). A finite group may act faithfully on a set of size much smaller than its cardinality (however such an action cannot be free). For instance the abelian 2-group (Z / 2Z)n (of cardinality 2n) acts faithfully on a set of size 2n. This is not always the case, for example the cyclic group Z / 2nZ cannot act faithfully on a set of size less than 2n.

In general the smallest set on which a faithful action can be defined can vary greatly for groups of the same size. For example, three groups of size 120 are the symmetric group S5, the icosahedral group A5 × Z / 2Z and the cyclic group Z / 120Z. The smallest sets on which faithful actions can be defined for these groups are of size 5, 7, and 16 respectively.

Transitivity properties

The action of G on X is called transitive if for any two points x, y ∈ X there exists a g ∈ G so that g ⋅ x = y.

The action is simply transitive (or sharply transitive, or regular) if it is both transitive and free. This means that given x, y ∈ X there is exactly one g ∈ G such that g ⋅ x = y. If X is acted upon simply transitively by a group G then it is called a principal homogeneous space for G or a G-torsor.

For an integer n ≥ 1, the action is n-transitive if X has at least n elements, and for any pair of n-tuples (x1, ..., xn), (y1, ..., yn) ∈ Xn with pairwise distinct entries (that is xi ≠ xj, yi ≠ yj when i ≠ j) there exists a g ∈ G such that g⋅xi = yi for i = 1, ..., n. In other words, the action on the subset of Xn of tuples without repeated entries is transitive. For n = 2, 3 this is often called double, respectively triple, transitivity. The class of 2-transitive groups (that is, subgroups of a finite symmetric group whose action is 2-transitive) and more generally multiply transitive groups is well-studied in finite group theory.

An action is when the action on tuples without repeated entries in Xn is sharply transitive.

Examples

The action of the symmetric group of X is transitive, in fact n-transitive for any n up to the cardinality of X. If X has cardinality n, the action of the alternating group is (n − 2)-transitive but not (n − 1)-transitive.

The action of the general linear group of a vector space V on the set V ∖ {0} of non-zero vectors is transitive, but not 2-transitive (similarly for the action of the special linear group if the dimension of v is at least 2). The action of the orthogonal group of a Euclidean space is not transitive on nonzero vectors but it is on the unit sphere.

Primitive actions

The action of G on X is called primitive if there is no partition of X preserved by all elements of G apart from the trivial partitions (the partition in a single piece and its dual, the partition into singletons).

Topological properties

Assume that X is a topological space and the action of G is by homeomorphisms.

The action is wandering if every x ∈ X has a neighbourhood U such that there are only finitely many g ∈ G with g⋅U ∩ U ≠ ∅.[4]

More generally, a point x ∈ X is called a point of discontinuity for the action of G if there is an open subset U ∋ x such that there are only finitely many g ∈ G with g⋅U ∩ U ≠ ∅. The domain of discontinuity of the action is the set of all points of discontinuity. Equivalently it is the largest G-stable open subset Ω ⊂ X such that the action of G on Ω is wandering.[5] In a dynamical context this is also called a wandering set.

The action is properly discontinuous if for every compact subset K ⊂ X there are only finitely many g ∈ G such that g⋅K ∩ K ≠ ∅. This is strictly stronger than wandering; for instance the action of Z on R2 ∖ {(0, 0)} given by n⋅(x, y) = (2nx, 2−ny) is wandering and free but not properly discontinuous.[6]

The action by deck transformations of the fundamental group of a locally simply connected space on a universal cover is wandering and free. Such actions can be characterized by the following property: every x ∈ X has a neighbourhood U such that g⋅U ∩ U = ∅ for every g ∈ G ∖ {eG}.[7] Actions with this property are sometimes called freely discontinuous, and the largest subset on which the action is freely discontinuous is then called the free regular set.[8]

An action of a group G on a locally compact space X is called cocompact if there exists a compact subset A ⊂ X such that X = G ⋅ A. For a properly discontinuous action, cocompactness is equivalent to compactness of the quotient space X / G.

Actions of topological groups

Now assume G is a topological group and X a topological space on which it acts by homeomorphisms. The action is said to be continuous if the map G × X → X is continuous for the product topology.

The action is said to be proper if the map G × X → X × X defined by (g, x) ↦ (x, g⋅x) is proper.[9] This means that given compact sets K, K′ the set of g ∈ G such that g⋅K ∩ K′ ≠ ∅ is compact. In particular, this is equivalent to proper discontinuity if G is a discrete group.

It is said to be locally free if there exists a neighbourhood U of eG such that g⋅x ≠ x for all x ∈ X and g ∈ U ∖ {eG}.

The action is said to be strongly continuous if the orbital map g ↦ g⋅x is continuous for every x ∈ X. Contrary to what the name suggests, this is a weaker property than continuity of the action. If G is a Lie group and X a differentiable manifold, then the subspace of smooth points for the action is the set of points x ∈ X such that the map g ↦ g⋅x is smooth. There is a well-developed theory of Lie group actions, i.e. action which are smooth on the whole space.

Linear actions

If g acts by linear transformations on a module over a commutative ring, the action is said to be irreducible if there are no proper nonzero g-invariant submodules. It is said to be semisimple if it decomposes as a direct sum of irreducible actions.

Orbits and stabilizers

Consider a group G acting on a set X. The orbit of an element x in X is the set of elements in X to which x can be moved by the elements of G. The orbit of x is denoted by G⋅x:

The defining properties of a group guarantee that the set of orbits of (points x in) X under the action of G form a partition of X. The associated equivalence relation is defined by saying x ~ y if and only if there exists a g in G with g⋅x = y. The orbits are then the equivalence classes under this relation; two elements x and y are equivalent if and only if their orbits are the same, that is, G⋅x = G⋅y.

The group action is transitive if and only if it has exactly one orbit, that is, if there exists x in X with G⋅x = X. This is the case if and only if G⋅x = X for all x in X (given that X is non-empty).

The set of all orbits of X under the action of G is written as X / G (or, less frequently, as G \ X), and is called the quotient of the action. In geometric situations it may be called the orbit space, while in algebraic situations it may be called the space of coinvariants, and written XG, by contrast with the invariants (fixed points), denoted XG: the coinvariants are a quotient while the invariants are a subset. The coinvariant terminology and notation are used particularly in group cohomology and group homology, which use the same superscript/subscript convention.

Invariant subsets

If Y is a subset of X, then G⋅Y denotes the set {g⋅y : g ∈ G and y ∈ Y}. The subset Y is said to be invariant under G if G⋅Y = Y (which is equivalent G⋅Y ⊆ Y). In that case, G also operates on Y by restricting the action to Y. The subset Y is called fixed under G if g⋅y = y for all g in G and all y in Y. Every subset that is fixed under G is also invariant under G, but not conversely.

Every orbit is an invariant subset of X on which G acts transitively. Conversely, any invariant subset of X is a union of orbits. The action of G on X is transitive if and only if all elements are equivalent, meaning that there is only one orbit.

A G-invariant element of X is x ∈ X such that g⋅x = x for all g ∈ G. The set of all such x is denoted XG and called the G-invariants of X. When X is a G-module, XG is the zeroth cohomology group of G with coefficients in X, and the higher cohomology groups are the derived functors of the functor of G-invariants.

Fixed points and stabilizer subgroups

Given g in G and x in X with g⋅x = x, it is said that "x is a fixed point of g" or that "g fixes x". For every x in X, the stabilizer subgroup of G with respect to x (also called the isotropy group or little group[10]) is the set of all elements in G that fix x: This is a subgroup of G, though typically not a normal one. The action of G on X is free if and only if all stabilizers are trivial. The kernel N of the homomorphism with the symmetric group, G → Sym(X), is given by the intersection of the stabilizers Gx for all x in X. If N is trivial, the action is said to be faithful (or effective).

Let x and y be two elements in X, and let g be a group element such that y = g⋅x. Then the two stabilizer groups Gx and Gy are related by Gy = gGxg−1.

Proof: by definition, h ∈ Gy if and only if h⋅(g⋅x) = g⋅x. Applying g−1 to both sides of this equality yields (g−1hg)⋅x = x; that is, g−1hg ∈ Gx.

An opposite inclusion follows similarly by taking h ∈ Gx and x = g−1⋅y.

The above says that the stabilizers of elements in the same orbit are conjugate to each other. Thus, to each orbit, we can associate a conjugacy class of a subgroup of G (that is, the set of all conjugates of the subgroup). Let (H) denote the conjugacy class of H. Then the orbit O has type (H) if the stabilizer Gx of some/any x in O belongs to (H). A maximal orbit type is often called a principal orbit type.

Orbit–stabilizer theorem

Orbits and stabilizers are closely related. For a fixed x in X, consider the map f : G → X given by g ↦ g⋅x. By definition the image f(G) of this map is the orbit G⋅x. The condition for two elements to have the same image is In other words, f(g) = f(h) if and only if g and h lie in the same coset for the stabilizer subgroup Gx. Thus, the fiber f−1({y}) of f over any y in G⋅x is contained in such a coset, and every such coset also occurs as a fiber. Therefore f induces a bijection between the set G / Gx of cosets for the stabilizer subgroup and the orbit G⋅x, which sends gGx ↦ g⋅x.[11] This result is known as the orbit–stabilizer theorem.

If G is finite then the orbit–stabilizer theorem, together with Lagrange's theorem, gives In other words, the length of the orbit of x times the order of its stabilizer is the order of the group. In particular that implies that the orbit length is a divisor of the group order.

- Example: Let G be a group of prime order p acting on a set X with k elements. Since each orbit has either 1 or p elements, there are at least k mod p orbits of length 1 which are G-invariant elements. More specifically, k and the number of G-invariant elements are congruent modulo p.[12]

This result is especially useful since it can be employed for counting arguments (typically in situations where X is finite as well).

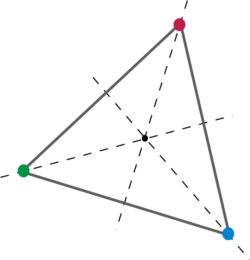

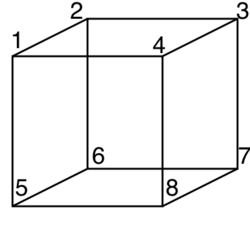

- Example: We can use the orbit–stabilizer theorem to count the automorphisms of a graph. Consider the cubical graph as pictured, and let G denote its automorphism group. Then G acts on the set of vertices {1, 2, ..., 8}, and this action is transitive as can be seen by composing rotations about the center of the cube. Thus, by the orbit–stabilizer theorem, |G| = |G ⋅ 1| |G1| = 8 |G1|. Applying the theorem now to the stabilizer G1, we can obtain |G1| = |(G1) ⋅ 2| |(G1)2|. Any element of G that fixes 1 must send 2 to either 2, 4, or 5. As an example of such automorphisms consider the rotation around the diagonal axis through 1 and 7 by 2π/3, which permutes 2, 4, 5 and 3, 6, 8, and fixes 1 and 7. Thus, |(G1) ⋅ 2| = 3. Applying the theorem a third time gives |(G1)2| = |((G1)2) ⋅ 3| |((G1)2)3|. Any element of G that fixes 1 and 2 must send 3 to either 3 or 6. Reflecting the cube at the plane through 1, 2, 7 and 8 is such an automorphism sending 3 to 6, thus |((G1)2) ⋅ 3| = 2. One also sees that ((G1)2)3 consists only of the identity automorphism, as any element of G fixing 1, 2 and 3 must also fix all other vertices, since they are determined by their adjacency to 1, 2 and 3. Combining the preceding calculations, we can now obtain |G| = 8 ⋅ 3 ⋅ 2 ⋅ 1 = 48.

Burnside's lemma

A result closely related to the orbit–stabilizer theorem is Burnside's lemma: where Xg is the set of points fixed by g. This result is mainly of use when G and X are finite, when it can be interpreted as follows: the number of orbits is equal to the average number of points fixed per group element.

Fixing a group G, the set of formal differences of finite G-sets forms a ring called the Burnside ring of G, where addition corresponds to disjoint union, and multiplication to Cartesian product.

Examples

- The trivial action of any group G on any set X is defined by g⋅x = x for all g in G and all x in X; that is, every group element induces the identity permutation on X.[13]

- In every group G, left multiplication is an action of G on G: g⋅x = gx for all g, x in G. This action is free and transitive (regular), and forms the basis of a rapid proof of Cayley's theorem – that every group is isomorphic to a subgroup of the symmetric group of permutations of the set G.

- In every group G with subgroup H, left multiplication is an action of G on the set of cosets G / H: g⋅aH = gaH for all g, a in G. In particular if H contains no nontrivial normal subgroups of G this induces an isomorphism from G to a subgroup of the permutation group of degree [G : H].

- In every group G, conjugation is an action of G on G: g⋅x = gxg−1. An exponential notation is commonly used for the right-action variant: xg = g−1xg; it satisfies (xg)h = xgh.

- In every group G with subgroup H, conjugation is an action of G on conjugates of H: g⋅K = gKg−1 for all g in G and K conjugates of H.

- An action of Z on a set X uniquely determines and is determined by an automorphism of X, given by the action of 1. Similarly, an action of Z / 2Z on X is equivalent to the data of an involution of X.

- The symmetric group Sn and its subgroups act on the set {1, ..., n} by permuting its elements

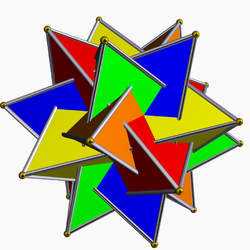

- The symmetry group of a polyhedron acts on the set of vertices of that polyhedron. It also acts on the set of faces or the set of edges of the polyhedron.

- The symmetry group of any geometrical object acts on the set of points of that object.

- For a coordinate space V over a field F with group of units F*, the mapping F* × V → V given by a × (x1, x2, ..., xn) ↦ (ax1, ax2, ..., axn) is a group action called scalar multiplication.

- The automorphism group of a vector space (or graph, or group, or ring ...) acts on the vector space (or set of vertices of the graph, or group, or ring ...).

- The general linear group GL(n, K) and its subgroups, particularly its Lie subgroups (including the special linear group SL(n, K), orthogonal group O(n, K), special orthogonal group SO(n, K), and symplectic group Sp(n, K)) are Lie groups that act on the vector space Kn. The group operations are given by multiplying the matrices from the groups with the vectors from Kn.

- The general linear group GL(n, Z) acts on Zn by natural matrix action. The orbits of its action are classified by the greatest common divisor of coordinates of the vector in Zn.

- The affine group acts transitively on the points of an affine space, and the subgroup V of the affine group (that is, a vector space) has transitive and free (that is, regular) action on these points;[14] indeed this can be used to give a definition of an affine space.

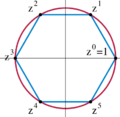

- The projective linear group PGL(n + 1, K) and its subgroups, particularly its Lie subgroups, which are Lie groups that act on the projective space Pn(K). This is a quotient of the action of the general linear group on projective space. Particularly notable is PGL(2, K), the symmetries of the projective line, which is sharply 3-transitive, preserving the cross ratio; the Möbius group PGL(2, C) is of particular interest.

- The sets acted on by a group G comprise the category of G-sets in which the objects are G-sets and the morphisms are G-set homomorphisms: functions f : X → Y such that g⋅(f(x)) = f(g⋅x) for every g in G.

- The Galois group of a field extension L / K acts on the field L but has only a trivial action on elements of the subfield K. Subgroups of Gal(L / K) correspond to subfields of L that contain K, that is, intermediate field extensions between L and K.

- The additive group of the real numbers (R, +) acts on the phase space of "well-behaved" systems in classical mechanics (and in more general dynamical systems) by time translation: if t is in R and x is in the phase space, then x describes a state of the system, and t + x is defined to be the state of the system t seconds later if t is positive or −t seconds ago if t is negative.

- The additive group of the real numbers (R, +) acts on the set of real functions of a real variable in various ways, with (t⋅f)(x) equal to, for example, f(x + t), f(x) + t, f(xet), f(x)et, f(x + t)et, or f(xet) + t, but not f(xet + t).

- Given a group action of G on X, we can define an induced action of G on the power set of X, by setting g⋅U = {g⋅u : u ∈ U} for every subset U of X and every g in G. This is useful, for instance, in studying the action of the large Mathieu group on a 24-set and in studying symmetry in certain models of finite geometries.

- The quaternions with norm 1 (the versors), as a multiplicative group, act on R3: for any such quaternion z = cos α/2 + v sin α/2, the mapping f(x) = zxz* is a counterclockwise rotation through an angle α about an axis given by a unit vector v; z is the same rotation; see quaternions and spatial rotation. This is not a faithful action because the quaternion −1 leaves all points where they were, as does the quaternion 1.

- Given left G-sets X, Y, there is a left G-set YX whose elements are G-equivariant maps α : X × G → Y, and with left G-action given by g⋅α = α ∘ (idX × –g) (where "–g" indicates right multiplication by g). This G-set has the property that its fixed points correspond to equivariant maps X → Y; more generally, it is an exponential object in the category of G-sets.

Group actions and groupoids

The notion of group action can be encoded by the action groupoid G′ = G ⋉ X associated to the group action. The stabilizers of the action are the vertex groups of the groupoid and the orbits of the action are its components.

Morphisms and isomorphisms between G-sets

If X and Y are two G-sets, a morphism from X to Y is a function f : X → Y such that f(g⋅x) = g⋅f(x) for all g in G and all x in X. Morphisms of G-sets are also called equivariant maps or G-maps.

The composition of two morphisms is again a morphism. If a morphism f is bijective, then its inverse is also a morphism. In this case f is called an isomorphism, and the two G-sets X and Y are called isomorphic; for all practical purposes, isomorphic G-sets are indistinguishable.

Some example isomorphisms:

- Every regular G action is isomorphic to the action of G on G given by left multiplication.

- Every free G action is isomorphic to G × S, where S is some set and G acts on G × S by left multiplication on the first coordinate. (S can be taken to be the set of orbits X / G.)

- Every transitive G action is isomorphic to left multiplication by G on the set of left cosets of some subgroup H of G. (H can be taken to be the stabilizer group of any element of the original G-set.)

With this notion of morphism, the collection of all G-sets forms a category; this category is a Grothendieck topos (in fact, assuming a classical metalogic, this topos will even be Boolean).

Variants and generalizations

We can also consider actions of monoids on sets, by using the same two axioms as above. This does not define bijective maps and equivalence relations however. See semigroup action.

Instead of actions on sets, we can define actions of groups and monoids on objects of an arbitrary category: start with an object X of some category, and then define an action on X as a monoid homomorphism into the monoid of endomorphisms of X. If X has an underlying set, then all definitions and facts stated above can be carried over. For example, if we take the category of vector spaces, we obtain group representations in this fashion.

We can view a group G as a category with a single object in which every morphism is invertible.[15] A (left) group action is then nothing but a (covariant) functor from G to the category of sets, and a group representation is a functor from G to the category of vector spaces.[16] A morphism between G-sets is then a natural transformation between the group action functors.[17] In analogy, an action of a groupoid is a functor from the groupoid to the category of sets or to some other category.

In addition to continuous actions of topological groups on topological spaces, one also often considers smooth actions of Lie groups on smooth manifolds, regular actions of algebraic groups on algebraic varieties, and actions of group schemes on schemes. All of these are examples of group objects acting on objects of their respective category.

Gallery

-

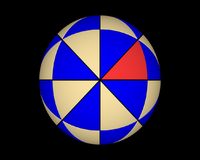

Orbit of a fundamental spherical triangle (marked in red) under action of the full octahedral group.

-

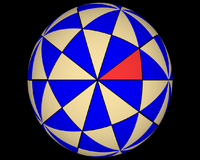

Orbit of a fundamental spherical triangle (marked in red) under action of the full icosahedral group.

See also

- Gain graph

- Group with operators

- Measurable group action

- Monoid action

- Young–Deruyts development

Notes

Citations

- ↑ Eie & Chang (2010). A Course on Abstract Algebra. p. 144. https://books.google.com/books?id=jozIZ0qrkk8C&pg=PA144&dq=%22group+action%22.

- ↑ This is done, for example, by Smith (2008). Introduction to abstract algebra. p. 253. https://books.google.com/books?id=PQUAQh04lrUC&pg=PA253&dq=%22group+action%22.

- ↑ "Definition:Right Group Action Axioms". https://proofwiki.org/wiki/Definition:Right_Group_Action_Axioms.

- ↑ Thurston 1997, Definition 3.5.1(iv).

- ↑ Kapovich 2009, p. 73.

- ↑ Thurston 1980, p. 176.

- ↑ Hatcher 2002, p. 72.

- ↑ Maskit 1988, II.A.1, II.A.2.

- ↑ tom Dieck 1987.

- ↑ Procesi, Claudio (2007) (in en). Lie Groups: An Approach through Invariants and Representations. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 5. ISBN 9780387289298. https://books.google.com/books?id=Sl8OAGYRz_AC&q=%22little+group%22+action&pg=PA5. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ↑ M. Artin, Algebra, Proposition 6.8.4 on p. 179

- ↑ Carter, Nathan (2009). Visual Group Theory (1st ed.). The Mathematical Association of America. pp. 200. ISBN 978-0883857571.

- ↑ Eie & Chang (2010). A Course on Abstract Algebra. p. 145. https://books.google.com/books?id=jozIZ0qrkk8C&pg=PA144&dq=%22trivial+action%22.

- ↑ Reid, Miles (2005). Geometry and topology. Cambridge, UK New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 170. ISBN 9780521613255.

- ↑ Perrone (2024), pp. 7–9

- ↑ Perrone (2024), pp. 36–39

- ↑ Perrone (2024), pp. 69–71

References

- Aschbacher, Michael (2000). Finite Group Theory. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78675-1.

- Dummit, David; Richard Foote (2003). Abstract Algebra (3rd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0-471-43334-9.

- Eie, Minking; Chang, Shou-Te (2010). A Course on Abstract Algebra. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-4271-88-2.

- Hatcher, Allen (2002), Algebraic Topology, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-79540-1, https://pi.math.cornell.edu/~hatcher/AT/ATpage.html.

- Rotman, Joseph (1995). An Introduction to the Theory of Groups. Graduate Texts in Mathematics 148 (4th ed.). Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-94285-8.

- Smith, Jonathan D.H. (2008). Introduction to abstract algebra. Textbooks in mathematics. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-6371-4.

- Kapovich, Michael (2009), Hyperbolic manifolds and discrete groups, Modern Birkhäuser Classics, Birkhäuser, pp. xxvii+467, ISBN 978-0-8176-4912-8

- Maskit, Bernard (1988), Kleinian groups, Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften, 287, Springer-Verlag, pp. XIII+326

- Perrone, Paolo (2024), Starting Category Theory, World Scientific, doi:10.1142/9789811286018_0005, ISBN 978-981-12-8600-1

- Thurston, William (1980), The geometry and topology of three-manifolds, Princeton lecture notes, p. 175, http://library.msri.org/books/gt3m/, retrieved 2016-02-08

- Thurston, William P. (1997), Three-dimensional geometry and topology. Vol. 1., Princeton Mathematical Series, 35, Princeton University Press, pp. x+311

- tom Dieck, Tammo (1987), Transformation groups, de Gruyter Studies in Mathematics, 8, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co., p. 29, doi:10.1515/9783110858372.312, ISBN 978-3-11-009745-0, https://books.google.com/books?id=azcQhi6XeioC

External links

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Action of a group on a manifold", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=p/a010550

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "Group Action". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/GroupAction.html.

|

KSF

KSF