Haven (graph theory)

From HandWiki - Reading time: 8 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 8 min

In graph theory, a haven is a certain type of function on sets of vertices in an undirected graph. If a haven exists, it can be used by an evader to win a pursuit–evasion game on the graph, by consulting the function at each step of the game to determine a safe set of vertices to move into. Havens were first introduced by (Seymour Thomas) as a tool for characterizing the treewidth of graphs.[1] Their other applications include proving the existence of small separators on minor-closed families of graphs,[2] and characterizing the ends and clique minors of infinite graphs.[3][4]

Definition

If G is an undirected graph, and X is a set of vertices, then an X-flap is a nonempty connected component of the subgraph of G formed by deleting X. A haven of order k in G is a function β that assigns an X-flap β(X) to every set X of fewer than k vertices. This function must also satisfy additional constraints which are given differently by different authors. The number k is called the order of the haven.[5]

In the original definition of Seymour and Thomas,[1] a haven is required to satisfy the property that every two flaps β(X) and β(Y) must touch each other: either they share a common vertex or there exists an edge with one endpoint in each flap. In the definition used later by Alon, Seymour, and Thomas,[2] havens are instead required to satisfy a weaker monotonicity property: if X ⊆ Y, and both X and Y have fewer than k vertices, then β(Y) ⊆ β(X). The touching property implies the monotonicity property, but not necessarily vice versa. However, it follows from the results of Seymour and Thomas[1] that, in finite graphs, if a haven with the monotonicity property exists, then one with the same order and the touching property also exists.

Havens with the touching definition are closely related to brambles, families of connected subgraphs of a given graph that all touch each other. The order of a bramble is the minimum number of vertices needed in a set of vertices that hits all of the subgraphs in the family. The set of flaps β(X) for a haven of order k (with the touching definition) forms a bramble of order at least k, because any set Y of fewer than k vertices fails to hit the subgraph β(Y). Conversely, from any bramble of order k, one may construct a haven of the same order, by defining β(X) (for each choice of X) to be the X-flap that includes all of the subgraphs in the bramble that are disjoint from X. The requirement that the subgraphs in the bramble all touch each other can be used to show that this X-flap exists, and that all of the flaps β(X) chosen in this way touch each other. Thus, a graph has a bramble of order k if and only if it has a haven of order k.

Example

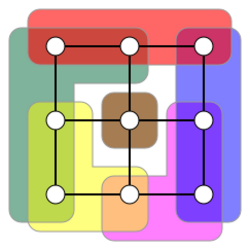

As an example, let G be a nine-vertex grid graph. Define a haven of order 4 in G, mapping each set X of three or fewer vertices to an X-flap β(X), as follows:

- If there is a unique X-flap that is larger than any of the other X-flaps, let β(X) be that unique large X-flap.

- Otherwise, choose β(X) arbitrarily to be any X-flap.

It is straightforward to verify by a case analysis that this function β satisfies the required monotonicity property of a haven. If X ⊆ Y and X has fewer than two vertices, or X has two vertices that are not the two neighbors of a corner vertex of the grid, then there is only one X-flap and it contains every Y-flap. In the remaining case, X consists of the two neighbors of a corner vertex and has two X-flaps: one consisting of that corner vertex, and another (chosen as β(X)) consisting of the six remaining vertices. No matter which vertex is added to X to form Y, there will be a Y-flap with at least four vertices, which must be the unique largest flap since it contains more than half of the vertices not in Y. This large Y-flap will be chosen as β(Y) and will be a subset of β(X). Thus in each case monotonicity holds.

Pursuit–evasion

Havens model a certain class of strategies for an evader in a pursuit–evasion game in which fewer than k pursuers attempt to capture a single evader, the pursuers and evader are both restricted to the vertices of a given undirected graph, and the positions of the pursuers and evader are known to both players. At each move of the game, a new pursuer may be added to an arbitrary vertex of the graph (as long as fewer than k pursuers are placed on the graph at any time) or one of the already-added pursuers may be removed from the graph. However, before a new pursuer is added, the evader is first informed of its new location and may move along the edges of the graph to any unoccupied vertex. While moving, the evader may not pass through any vertex that is already occupied by any of the pursuers.

If a k-haven (with the monotonicity property) exists, then the evader may avoid being captured indefinitely, and win the game, by always moving to a vertex of β(X) where X is the set of vertices that will be occupied by pursuers at the end of the move. The monotonicity property of a haven guarantees that, when a new pursuer is added to a vertex of the graph, the vertices in β(X) are always reachable from the current position of the evader.[1]

For instance, an evader can win this game against three pursuers on a 3 × 3 grid by following this strategy with the haven of order 4 described in the example. However, on the same graph, four pursuers can always capture the evader, by first moving onto three vertices that split the grid onto two three-vertex paths, then moving into the center of the path containing the evader, forcing the evader into one of the corner vertices, and finally removing one of the pursuers that is not adjacent to this corner and placing it onto the evader. Therefore, the 3 × 3 grid can have no haven of order 5.

Havens with the touching property allow the evader to win the game against more powerful pursuers that may simultaneously jump from one set of occupied vertices to another.[1]

Connections to treewidth, separators, and minors

Havens may be used to characterize the treewidth of graphs: a graph has a haven of order k if and only if it has treewidth at least k – 1. A tree decomposition may be used to describe a winning strategy for the pursuers in the same pursuit–evasion game, so it is also true that a graph has a haven of order k if and only if the evader wins with best play against fewer than k pursuers. In games won by the evader, there is always an optimal strategy in the form described by a haven, and in games won by the pursuer, there is always an optimal strategy in the form described by a tree decomposition.[1] For instance, because the 3 × 3 grid has a haven of order 4, but does not have a haven of order 5, it must have treewidth exactly 3. The same min-max theorem can be generalized to infinite graphs of finite treewidth, with a definition of treewidth in which the underlying tree is required to be rayless (that is, having no ends).[1]

Havens are also closely related to the existence of separators, small sets X of vertices in an n-vertex graph such that every X-flap has at most 2n⁄3 vertices. If a graph G does not have a k-vertex separator, then every set X of at most k vertices has a (unique) X-flap with more than 2n⁄3 vertices. In this case, G has a haven of order k + 1, in which β(X) is defined to be this unique large X-flap. That is, every graph has either a small separator or a haven of high order.[2]

If a graph G has a haven of order k, with k ≥ h3/2n1/2 for some integer h, then G must also have a complete graph Kh as a minor. In other words, the Hadwiger number of an n-vertex graph with a haven of order k is at least k2/3n-1/3. As a consequence, the Kh-minor-free graphs have treewidth less than h3/2n1/2 and separators of size less than h3/2n1/2. More generally an bound on treewidth and separator size holds for any nontrivial family of graphs that can be characterized by forbidden minors, because for any such family there is a constant h such that the family does not include Kh.[2]

In infinite graphs

If a graph G contains a ray, a semi-infinite simple path with a starting vertex but no ending vertex, then it has a haven of order ℵ0: that is, a function β that maps each finite set X of vertices to an X-flap, satisfying the consistency condition for havens. Namely, define β(X) to be the unique X-flap that contains infinitely many vertices of the ray. Thus, in the case of infinite graphs the connection between treewidth and havens breaks down: a single ray, despite itself being a tree, has havens of all finite orders and even more strongly a haven of order ℵ0. Two rays of an infinite graph are considered to be equivalent if there is no finite set of vertices that separates infinitely many vertices of one ray from infinitely many vertices of the other ray; this is an equivalence relation, and its equivalence classes are called ends of the graph.

The ends of any graph are in one-to-one correspondence with its havens of order ℵ0. For, every ray determines a haven, and every two equivalent rays determine the same haven.[3] Conversely, every haven is determined by a ray in this way, as can be shown by the following case analysis:

- If the haven has the property that the intersection

(where the intersection ranges over all finite sets X) is itself an infinite set S, then every finite simple path that ends in a vertex of S can be extended to reach an additional vertex of S, and repeating this extension process produces a ray passing through infinitely many vertices of S. This ray determines the given haven.

- On the other hand, if S is finite, then (by working in the subgraph G \ S)it can be assumed to be empty. In this case, for each finite set Xi of vertices there is a finite set Xi+1 with the property that Xi is disjoint from . If a robber follows the evasion strategy determined by the haven, and the police follow a strategy given by this sequence of sets, then the path followed by the robber forms a ray that determines the haven.[4]

Thus, every equivalence class of rays defines a unique haven, and every haven is defined by an equivalence class of rays.

For any cardinal number , an infinite graph G has a haven of order κ if and only if it has a clique minor of order κ. That is, for uncountable cardinalities, the largest order of a haven in G is the Hadwiger number of G.[3]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 "Graph searching and a min-max theorem for tree-width", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B 58 (1): 22–33, 1993, doi:10.1006/jctb.1993.1027.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "A separator theorem for nonplanar graphs", J. Amer. Math. Soc. 3 (4): 801–808, 1990, doi:10.1090/S0894-0347-1990-1065053-0.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Excluding infinite minors", Discrete Mathematics 95 (1-3): 303–319, 1991, doi:10.1016/0012-365X(91)90343-Z.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Diestel, Reinhard (2003), "Graph-theoretical versus topological ends of graphs", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B 87 (1): 197–206, doi:10.1016/S0095-8956(02)00034-5.

- ↑ "Directed Tree Width", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B 82 (1): 138–155, 2001, doi:10.1006/jctb.2000.2031.

|

KSF

KSF