Hill station

Topic: History

From HandWiki - Reading time: 9 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 9 min

A hill station is a town located at a higher elevation than the nearby plain or valley. The term was used mostly in colonial Asia (particularly in India), but also in Africa (albeit rarely), for towns founded by European colonialists as refuges from the summer heat and, as Dale Kennedy observes about the Indian context, "the hill station ... was seen as an exclusive British preserve: here it was possible to render the Indian into an outsider".[1][2] In India, which has the largest number of hill stations, most are situated at an altitude of approximately 1,000 to 2,500 metres (3,300 to 8,200 ft).

History

In South Asia

Some view Nandi Hills, an 11th-century hilltop fortress developed by the Ganga dynasty in present-day Karnataka, India, as a precursor to the hill station concept.[3][4] Tipu Sultan (1751 - 1799) notably used it as a summer retreat.[5]

Hill stations in British India were established for a variety of reasons. One of the first reasons in the early 1800s, was for the place to act as a sanitorium for the ailing family members of British officials.[6] After the rebellion of 1857, the British "sought further distance from what they saw as a disease-ridden land by [escaping] to the Himalayas in the north". Other factors included anxieties about the dangers of life in India, among them "fear of degeneration brought on by too long residence in a debilitating land". The hill stations were meant to reproduce the home country, illustrated in Lord Lytton's statement about Ootacamund in the 1870s as having "such beautiful English rain, such delicious English mud."[7] Shimla was officially made the "summer capital of India" in the 1860s and hill stations "served as vital centres of political and military power, especially after the 1857 revolt."[8][9]

As noted by Indian historian Vinay Lal, hill stations in India also served "as spaces for the colonial structuring of a segregational and ontological divide between Indians and Europeans, and as institutional sites of imperial power."[10][11][12][13][14][15][16] [17][18] William Dalrymple wrote that "The viceroy was the spider at the heart of Simla's web: From his chambers in Viceregal Lodge, he pulled the strings of an empire that stretched from Rangoon in the east to Aden in the west."[19] Meanwhile Judith T Kenny observed that "the hill station as a landscape type tied to nineteenth-century discourses of imperialism and climate. Both discourses serve as evidence of a belief in racial difference and, thereby, the imperial hill station reflected and reinforced a framework of meaning that influenced European views of the non-western world in general."[20] The historian of Himalayan cultures Shekhar Pathak speaking about the development of Hill Stations like Mussoorie noted that “the needs of this (European) elite created colonies in Dehradun of Indians to cater to them."[21] This "exclusive, clean, and secure social space – known as an enclave – for white Europeans ... evolved to become the seats of government and foci of elite social activity", and created racial distinctions which perpetuated British colonial power and oppression as Nandini Bhattacharya notes.[22][23] Dale Kennedy observed that "the hill station, then, was seen as an exclusive British preserve: here it was possible to render the Indian into an outsider".[1]

Kennedy, following Monika Bührlein, identifies three stages in the evolution of hill stations in India: high refuge, high refuge to hill station, and hill station to town. The first settlements started in the 1820s, primarily as sanitoria. In the 1840s and 1850s, there was a wave of new hill stations, with the main impetus being "places to rest and recuperate from the arduous life on the plains". In the second half of the 19th century, there was a period of consolidation with few new hill stations. In the final phase, "hill stations reached their zenith in the late nineteenth century. The political importance of the official stations was underscored by the inauguration of large and costly public-building projects."[8]:14

The concept of Hill Station has been used loosely in India (and more broadly South Asia) since the mid-20th century to qualify any town or settlement in mountainous areas, which attempt to expand its local economy toward tourism, or have been invested by recent mass tourism practices. Kullu and Manali in the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh, are two example of that misuse of Hill Station or more accurately deviation of its meaning. These two historical settlements existed prior to the British, and haven't been specially frequented by them or even extensively modified or shaped by them. However, the rise of internal domestic tourism in India from the eighties and the subsequent reproduction of Hill Station practice by urban middle-class Indians contributed to the labelling of these two localities as Hill Stations. Munnar, a settlement in the state of Kerala whose economy is primarily based on tea cultivation and processing, as well as plantations agriculture, is another example of a hill town transformed by contemporaneous tourism practices as a hill station.

List of hill stations

Most hill stations, listed by region:

Africa

Madagascar

Morocco

Nigeria

- Jos

Uganda

- Fort Portal

Americas

Brazil

- Petropolis

- Campos do Jordão

Costa Rica

- Monteverde

United States

- Beech Mountain

- Sky Valley, Georgia

- Big Bear Lake, California

- Cloudcroft, New Mexico

- Summerhaven, Arizona

Asia

Bangladesh

- Chittagong

- Sajek Valley

- Bandarban,Chittagong

- Jaflong

- Khagrachari,Chittagong

- Moulvibazar

- Rangamati,Chittagong

- Sreemangal

Cambodia

- Bokor Hill Station

China

- Kuling (Guling) in Jiangxi Province

- Mount Mogan

- Mount Jigong

- Guling, Fujian Province

- Beidaihe

Cyprus

- Platres

Hong Kong

- Victoria Peak

- Sunset Peak

India

Hundreds of hill stations are located in India. The most popular hill stations in India include:

- Achabal, Jammu and Kashmir

- Amarkantak, Madhya Pradesh

- Ambanad Hills, Kerala

- Amboli, Maharashtra

- Almora, Uttarakhand

- Araku Valley, Andhra Pradesh

- Aritar, Sikkim

- Aru, Jammu and Kashmir

- Askot, Uttarakhand

- Auli, Uttarakhand

- Baba Budan giri, Karnataka

- Badrinath, Uttarakhand

- Baltal, Jammu and Kashmir

- Barog, Himachal Pradesh

- Berinag, Uttarakhand

- Bhaderwah, Jammu and Kashmir

- Bhowali, Uttarakhand

- Chail, Himachal Pradesh

- Chakrata, Uttarakhand

- Chamba, Himachal Pradesh

- Champhai, Mizoram

- Chaukori, Uttarakhand

- Cherrapunjee, Meghalaya

- Chikhaldara, Maharashtra

- Chitkul, Himachal Pradesh

- Coonoor, Tamil Nadu

- Daksum, Jammu and Kashmir

- Dalhousie, Himachal Pradesh

- Daringbadi, Odisha

- Darjeeling, West Bengal

- Dawki, Meghalaya

- Diskit, Ladakh

- Doodhpathri, Jammu and Kashmir

- Dhanaulti, Uttarakhand

- Dharamkot, Himachal Pradesh

- Dharchula, Uttarakhand

- Dras, Ladakh

- Dzuluk, Sikkim

- Dzüko Valley, Nagaland and Manipur

- Gairsain, Uttarakhand

- Gangtok, Sikkim

- Ghum, West Bengal

- Gulmarg, Jammu and Kashmir

- Geyzing, Sikkim

- Haflong, Assam

- Hemkund Sahib, Uttarakhand

- Hmuifang, Mizoram

- Kalpa, Himachal Pradesh

- Jogindernagar, Himachal Pradesh

- Jogimatti, Karnataka

- Joshimath, Uttarakhand

- Kalimpong, West Bengal

- Katra, Jammu and Kashmir

- Kangra, Himachal Pradesh

- Kargil, Ladakh

- Karzok, Ladakh

- Kedarnath, Uttarakhand

- Keylong, Himachal Pradesh

- Khajjiar, Himachal Pradesh

- Kodaikanal, Tamil Nadu

- Kolli Hills, Tamil Nadu

- Kotagiri, Tamil Nadu

- Kohima, Nagaland

- Kokernag, Jammu and Kashmir

- Khandala, Maharashtra

- Kufri, Himachal Pradesh

- Kullu, Himachal Pradesh

- Kurseong, West Bengal

- Lachen, Sikkim

- Lachung, Sikkim

- Lansdowne, Uttarakhand

- Lava, West Bengal

- Leh, Ladakh

- Lonavala, Maharashtra

- Lolegaon, West Bengal

- Lunglei, Mizoram

- Mahabaleshwar, Maharashtra

- Mainpat, Chhattisgarh

- Matheran, Maharashtra

- Manali, Himachal Pradesh

- Mawsynram, Meghalaya

- McLeod Ganj, Himachal Pradesh

- Meghamalai, Tamil Nadu

- Mirik, West Bengal

- Mount Abu, Rajasthan

- Murgo, Ladakh

- Munnar, Kerala

- Munsiyari, Uttarakhand

- Mussoorie, Uttarakhand

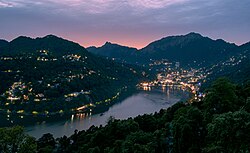

- Nainital, Uttarakhand

- Narkanda, Himachal Pradesh

- New Tehri, Uttarakhand

- Ooty (Udhagamandalam), Tamil Nadu

- Pachmarhi, Madhya Pradesh

- Palampur, Himachal Pradesh

- Pahalgam, Jammu and Kashmir

- Patnitop, Jammu and Kashmir

- Pauri, Uttarakhand

- Pelling, Sikkim

- Pfütsero, Nagaland

- Pithoragarh, Uttarakhand

- Ramgarh, Uttarakhand

- Ranikhet, Uttarakhand

- Reckong Peo, Himachal Pradesh

- Reiek, Mizoram

- Rishyap, West Bengal

- Samsing, West Bengal

- Saputara, Gujarat

- Shillong, Meghalaya

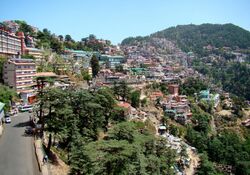

- Shimla, Himachal Pradesh

- Sonamarg, Jammu and Kashmir

- Soordelu Hill Station, Kerala

- Tawang, Arunachal Pradesh

- Thekkady, Kerala

- Triund, Himachal Pradesh

- Tosa Maidan, Jammu and Kashmir

- Topslip, Tamil Nadu

- Turtuk, Ladakh

- Uttarkashi, Uttarakhand

- Valparai, Tamil Nadu

- Vagamon, Kerala

- Verinag, Jammu and Kashmir

- Wilson Hills, Gujarat

- Yercaud Tamil Nadu

- Yelagiri Tamil Nadu

- Yusmarg, Jammu and Kashmir

- Yuksom, Sikkim

- Yumthang, Sikkim

Indonesia

- Garut in, West Java

- Sukabumi in West Java

- Puncak in West Java

- Batu in East Java

- Tretes in East Java

- Kaliurang in Central Java

- Munduk in Bali

- Bedugul in Bali

- Berastagi in North Sumatra

- Lembang in West Java

- Baturaden in Central Java

- Wonosobo in Central Java

- Tawangmangu in Central Java

- Bandungan, Semarang in Central Java

- Bukittinggi in West Sumatra

- Padang Panjang in West Sumatra

- Sawahlunto in West Sumatra

- Solok in West Sumatra

- Payakumbuh in West Sumatra

- Takengon in Aceh

- Tomohon in North Sulawesi

- Tana Toraja in South Sulawesi

- Malino in South Sulawesi

- Salatiga in Central Java

Iraq

- Shaqlawa

- Amedi

- Rawanduz

- Sulaymaniyah

- Batifa

Israel

- Metula

- Safed

Japan

Jordan

- A few suburbs in Amman:

- Al-Ashrafiya

- Jabal Amman

Malaysia

- Bukit Larut

- Bukit Tinggi

- Cameron Highlands

- Fraser's Hill

- Penang Hill

Myanmar

- Kalaw

- Pyin Oo Lwin

- Taunggyi

- Thandaung

Nepal

- Pokhara

- Namche Bazaar

- Bandipur

- Dhulikhel

- Tansen

- Nagarkot

- Kakani

- Gorkha Bazaar

- Daman

- Dharan

- Dhankuta

- Illam

- Sarangkot

- Baglung

- Resunga

- Kunde

- Khumjung

- Lukla

- Tengboche

- Phortse

- Bhimeshwar

- Besisahar

- Sandhikharka

- Tamghas

- Jomsom

- Phidim

- Phungling

- Fikal

- Bhedetar

- Dunai, Nepal

Pakistan

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

- Abbottabad

- Behrain

- Kalam Valley

- Malam Jabba

- Nathia Gali

- Shogran

- Chitral

- Jahaz Banda

- Naran

- Kaghan

Punjab

- Bhurban

- Charra Pani

- Murree

- Patriata

Sindh

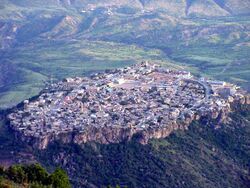

- Gorakh Hill

- Bado Hill Station

Balochistan

- Ziarat

Gilgit Baltistan

- Hunza Valley

- Skardu

- Astore Valley

- Gilgit

- Nagar Valley

Philippines

- Baguio

- Salvador Benedicto

- Mambukal

- Tagaytay

- Sagada

- Malaybalay

Sri Lanka

- Nuwara Eliya

Syria

- Bloudan

- Masyaf

- Qadmous

- Zabadani

- Madaya

Vietnam

- Da Lat

- Sa Pa

- Tam Đảo

- Bà Nà Hills

- Bạch Mã National Park

Oceania

Australia

Victoria

- Mount Macedon

- Harrietville

South Australia

- Mount Gambier

- Adelaide Hills

Queensland

- Toowoomba

- Merewether

- The Gap

- Chapel Hill

- Bardon

- Ferny Grove

- Buderim

- New Auckland

- Mount Archer

Western Australia

- Lesmurdie

- Kalamunda

- Jarrahdale

- Bedfordale

New South Wales

- Blue Mountains

- Mount Pleasant

- Woonoona

- Kariong

- Illawarra escarpment (Stanwell Tops)

- Prospect Hill (Pemulwuy)

- Terrey Hills

- Berowra Heights

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Kennedy, Dane. The Magic Mountains: Hill Stations and the British Raj. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1996 1996. | http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft396nb1sf/

- ↑ "Hill Stations: Pinnacles of the Raj". https://southasia.ucla.edu/hill-stations-pinnacles-raj/.

- ↑ "Plans include beautification of the entire hill station to attract tourists". Outlook India. 26 February 2021. https://www.outlookindia.com/outlooktraveller/travelnews/story/71232/nandi-hills.

- ↑ Muni Nagraj. Āgama Aura Tripiṭaka, Eka Anuśilana: Language and Literature. p. 500.

- ↑ Myer, H. (1995). India 2001: Reference Encyclopedia. South Asia Publications. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-945921-42-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=F_BtAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ Dane Keith Kennedy (1996). The Magic Mountains: Hill Stations and the britishBritishRaj. University of California Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-520-20188-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=UveLzKDlZBEC&pg=PR9.

- ↑ Barbara D. Metcalf; Thomas R. Metcalf (2002). A Concise History of India. Cambridge University Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-521-63974-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=jGCBNTDv7acC.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Kennedy, Dane (1996). The Magic Mountains: Hill Stations and the British Raj. Berkeley: University of California Press. http://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=ft396nb1sf;brand=ucpress. Retrieved 19 Aug 2014.

- ↑ Vipin Pubby (1996). Shimla Then and Now. Indus Publishing. pp. 17–34. ISBN 978-81-7387-046-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=UrZ-ibfhMyMC&pg=PA17. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- ↑ "'But what about the railways ...?' The myth of Britain's gifts to India". March 8, 2017. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/mar/08/india-britain-empire-railways-myths-gifts.

- ↑ "Racism and stereotypes in colonial India's 'Instagram'". BBC News. 30 September 2018. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-india-45506092.

- ↑ "Segregation and the Social Relations of Place, Bombay, 1890–1910". https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271900472.

- ↑ "Login". http://searcharchives.bl.uk/primo_library/libweb/action/display.do?dscnt=1&elementId=0&recIdxs=0&frbrVersion=&scp.scps=scope%3A%28BL%29&frbg=&tab=local&displayMode=full&dstmp=1613819543550&srt=rank&ct=display&mode=Basic&dum=true&indx=1&recIds=IAMS040-000155711&renderMode=poppedOut&doc=IAMS040-000155711&vl(freeText0)=proceedings%20of%20the%20third%20meeting%20of%20the%20general%20malaria%20committee%20at%20madras&fn=search&vid=IAMS_VU2&tabs=detailsTab&fromLogin=true.

- ↑ Das, Shinjini. "India's initial coronavirus response carried echoes of the colonial era". http://theconversation.com/indias-initial-coronavirus-response-carried-echoes-of-the-colonial-era-135887.

- ↑ Group, British Medical Journal Publishing (January 26, 1901). "The Prophylaxis of Malaria". Br Med J 1 (2091): 240–242. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.2091.240. PMID 20759409. PMC 2400219. https://www.bmj.com/content/1/2091/240.

- ↑ "Hill Stations: Pinnacles of the Raj". https://southasia.ucla.edu/hill-stations-pinnacles-raj/.

- ↑ Climates & Constitutions: Health, Race, Environment and British Imperialism in India, 1600-1850. Oxford University Press. 1999. ISBN 978-0-19-564657-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=XyVuAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ "Login". http://searcharchives.bl.uk/primo_library/libweb/action/display.do?dscnt=1&elementId=4&recIdxs=4&frbrVersion=&frbg=&scp.scps=scope%3A%28BL%29&displayMode=full&tab=local&dstmp=1588006706183&srt=rank&ct=display&mode=Basic&dum=true&indx=5&recIds=IAMS041-003421110&fromLogin=true&renderMode=poppedOut&doc=IAMS041-003421110&vl(freeText0)=L%2FE%2F7%2F866%20&vid=IAMS_VU2&fn=search&tabs=detailsTab&fromLogin=true.

- ↑ Dalrymple, William (1999-09-26). "India's Green and Pleasant Land". The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/magazine/1999/09/26/indias-green-and-pleasant-land/5f15d3b6-b6b3-4c24-83e6-56956313d87e/. Retrieved 2022-06-11.

- ↑ Climate, Race, and Imperial Authority: The Symbolic Landscape of the British Hill Station in India | Judith T. Kenny | https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-8306.1995.tb01821.x

- ↑ "How not to develop a hill station". https://scroll.in/article/1012794/.

- ↑ Contagion and Enclaves: Tropical Medicine in Colonial India | Nandini Bhattacharya | https://liverpool.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.5949/UPO9781846317835/upso-9781846318290-chapter-2

- ↑ Bhattacharya N. (2013). Leisure, economy and colonial urbanism: Darjeeling, 1835-1930. Urban history, 40(3), 442–461. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0963926813000394

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 Walters, Trudie; Duncan, Tara (2 Oct 2017). Second Homes and Leisure: New perspectives on a forgotten relationship. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. ISBN 9781317400264. https://books.google.com/books?id=3RA4DwAAQBAJ&q=hill+stations+in+japan&pg=PT74.

Bibliography

- Crossette, Barbara. The Great Hill Stations of Asia. ISBN:0-465-01488-7.

- Kennedy, Dane. The Magic Mountains: Hill Stations and the British Raj (Full text, searchable). Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996. ISBN:0-520-20188-4, ISBN:978-0520201880.

External links

|

KSF

KSF