Kingdom of Norway (872–1397)

Topic: History

From HandWiki - Reading time: 20 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 20 min

Kingdom of Norway | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 872–1397 | |||||||||||||||

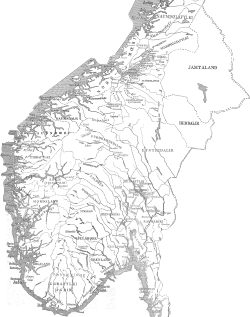

Norway at its greatest extent, around 1263 | |||||||||||||||

| Status |

| ||||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Majority languages:

Other languages:

Lingua franca:

Writing system:

| ||||||||||||||

| Religion | State religions:

| ||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Norwegian | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Feudal monarchy (872–1027) Unitary feudal monarchy (1027–1397) | ||||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||||

• 872–932 | Harald I (first) | ||||||||||||||

• 1387–1397 | Margaret I (last) | ||||||||||||||

| Legislature | None (872–c. 1000) Þing (i.e. Gulatingslǫg, Borgarþingslǫg, Heiðsævisþing, and Frostuþingslǫg) (c. 1000–c. 1300) Riksråd (c. 1300–1397) | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||||||

• Established | 872 | ||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1397 | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Norwegian penning (995–1397) | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | See: Loss of Norwegian possessions | ||||||||||||||

The term Norwegian Realm (Old Norse: *Noregsveldi, Bokmål: Norgesveldet, Nynorsk: Noregsveldet) and Old Kingdom of Norway refer to the Kingdom of Norway's peak of power at the 13th century after a long period of civil war before 1240. The kingdom was a loosely unified nation including the territory of modern-day Norway, modern-day Swedish territory of Jämtland, Herjedalen, Ranrike (Bohuslän) and Idre and Särna, as well as Norway's overseas possessions which had been settled by Norwegian seafarers for centuries before being annexed or incorporated into the kingdom as 'tax territories'. To the North, Norway also bordered extensive tax territories on the mainland. Norway, whose expansionism starts from the very foundation of the Kingdom in 872, reached the peak of its power in the years between 1240 and 1319.

At the peak of Norwegian expansion before the civil war (1130–1240), Sigurd I led the Norwegian Crusade (1107–1110). The crusaders won battles in Lisbon and the Balearic Islands. In the Siege of Sidon they fought alongside Baldwin I and Ordelafo Faliero, and the siege resulted in an expansion of the Kingdom of Jerusalem.[2] Leif Erikson, an Icelander of Norwegian origin and official hirdman of King Olaf I of Norway, explored America 500 years before Columbus.[3] Adam of Bremen wrote about the new lands in "Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum" (1076) when meeting Sweyn I of Denmark, but no other sources indicate that this knowledge went farther into Europe than Bremen, Germany. The Kingdom of Norway was the second European country after England to enforce a unified code of law to be applied for the whole country, called Magnus Lagabøtes landslov (1274).

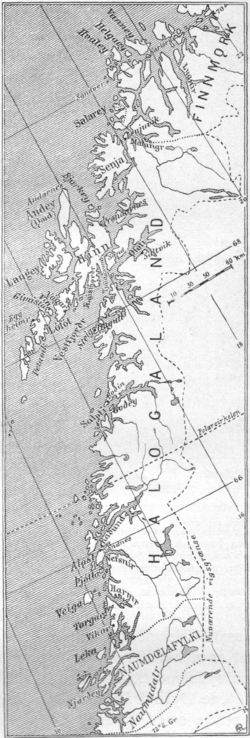

The secular power was at its strongest at the end of King Haakon Haakonsson's reign in 1263. An important element of the period was the ecclesiastical supremacy of the archdiocese of Nidaros from 1152. There are no reliable sources for when Jämtland was placed under the archbishop of Uppsala. Uppsala was established later, and was the third metropolitan diocese in Scandinavia after Lund and Nidaros. The church participated in a political process both before and during the Kalmar Union that aimed at[clarification needed] Swedish side, to establish a position for Sweden in Jämtland. This area had been a borderland in relation to the Swedish kingdom, and probably in some sort of alliance with Trøndelag, just as with Hålogaland.

A unified realm was initiated by King Harald I Fairhair in the 9th century. His efforts in unifying the petty kingdoms of Norway resulted in the first known Norwegian central government. The country, however, soon fragmented, and was again collected into one entity in the first half of the 11th century. Norway has been a monarchy since Fairhair, passing through several eras.

History

When Harald Fairhair became king of Norway after the battle at Hafrsfjord (traditional date: 18 July 872), he looked west to the isles that had been colonised by Norwegians for a century already, and by 875 the Northern Isles of Orkney and Shetland had been brought under his rule and given to Ragnvald Eysteinsson, Jarl of Møre.

Iceland was more reluctant to give up its independent rule, so the Icelandic saga author Snorri Sturluson was given a royal invitation to the court of King Haakon Haakonsson and was there convinced that Iceland was by right Norwegian. So began the Age of the Sturlungs, a time of political strife in Iceland. The Sturlungs worked to bring Iceland under Norwegian rule, spreading propaganda through their positions at the Althing and even resorting to violence before the Old Covenant was signed in 1262, which brought total Norwegian rule over the island.

In Ranríki Konunghella was built as a royal city alongside Túnsberg and Biorgvin. It remained Norwegian until the 1658 Roskilde treaty. Herjárdalr became Norwegian during the 12th century and remained so for five centuries. Jamtaland started paying taxes to Norway during the 13th century and was later absorbed into a part of the mainland territory the same century. It was occupied by the Swedish during the Nordic Seven Years' War, but later returned to Denmark-Norway as a result of the Stettin treaty of 1570. Idre and Særna, Norwegian since the 12th century, were conquered by Sweden during the Hannibal controversy. Ranríki, Herjárdalr, Jamtaland, Idre and Særna were permanently surrendered to Sweden by the Peace of Brömsebro 13 August 1645.

Mainland

Administrative divisions

Viken, counties under Borgarþing:

- Ránríki

- Vingulmórk

- Vestfold

- Grenafylki (extending to Tvedestrand)

Oppland, counties under Heiðsævisþing:

- Heinafylki (current day Hedmarken and Gjøvik)

- Haðafylki (consisting of Hadeland, Land, Ringerike, and Toten)

- Raumaríki (consisting of Glåmdalen, and Romerike)

- Guðbrandsdalir

- Eystridalir (including Särna and Idre)

Vestlandet, counties under Gulaþing:

- Sunnmærafylki

- Firðafylki (consisting of Nordfjord and Sunnfjord)

- Sygnafylki

- Horðafylki

- Rygjafylki

- Egðafylki

- Vøllðres

- Haddingjadalr

Trøndelag, counties under Frostaþing:

- Raumsdølafylki

- Norðmørafylki

- Naumdølafylki

- Sparbyggjafylki

- Eynafylki

- Verdølafylki

- Skeynafylki

- Stjórdølafylki

- Strindafylki

- Gauldølafylki

- Orkdølafylki

Norway , counties not attached to a thing:

- Jamtaland

- Herdalir

- Háleygjafylki

Tax territory

- Finnmòrk, as the areas north of Malangen, present-day Murmansk in Russia, and parts of northern Lapland in Finland.[citation needed]

Expansion and unification

From the 600s Western Norwegian fish farmers began an exodus to the nearby islands in the North Sea, Orkney and Shetland, and then later to the Western Isles, like the Hebrides and Man, and westward to the Faroe Islands, Iceland, and Greenland. Some of these islands were inhabited when the Norwegians arrived, but the local population was displaced or assimilated by the Norwegian immigrants.

Consistently, the islands' populations had a Norwegian ancestry, who kept in touch with the homeland over the North Sea. These Norwegians had their own chiefs or kings in the Norwegian tradition, subject to Norwegian royal power when it eventually developed a centralized state. Often, Norwegian kings had enough to contend with on the mainland, so the local power in the villages was often in the hands of local earls who operated on behalf of the king.

Holdings in Sweden were in varying degrees Norwegian. By the 9th and 10th centuries, it is reasonable to assume that the population of Båhuslen, Jämtland and Herjedalen had no national affiliation to Norway, Svealand, or Götaland. It lay to the increasingly centralized monarchy to create this, which had to consolidate its right in the border areas above the neighboring kingdoms. Norway was then the first to integrate these areas into its kingdom.

Overseas

Crown dependencies

- Ísland (Iceland)

- Grænland (Greenland)

- Færeyar (Faroe Islands)

- Mann (Isle of Man)

- Hjaltland (Shetland)

- Orkneyar (Orkney Islands)

- Suðreyar (The Hebrides)

Iceland, Faroe Islands and Greenland remained under Norwegian administration until 1814.

The treaty of Perth (1266) accepted Norwegian sovereignty over Shetland and Orkney; in turn Norway had to give the Hebrides and Isle of Man to Scotland.

Vassals

Vassals annexed by King Magnus III in 1098. Ireland

- Dyflin (Kingdom of Dublin)[4]

Scotland

Wales

- Anglesey[lower-alpha 3]

Areas governed by Norwegians independent from the Realm

England

- Northumbria

Eric I of Norway ruled Northumbria for two separate periods. Northumbria has also been ruled by Norway under Cnut the Great, as well as West Norse people of the British Isles. The most important city was called Jórvík (York).

France

- Normandy

The Duchy of Normandy was ruled by Norwegian and Danish Vikings, under the leadership of Rollo. Following extensive raids on Paris and vast areas in France, the duchy was founded in 911. The main purpose was to gain land for independent Vikings in this region, therefore Rollo swore a vassalage under France rather than Norway or Denmark. Although Rollo's ancestry is disputed, it is now common among British, French and Norwegian scientists to have the opinion that, judging from the sources and the possible two alternatives, more sources point to Norwegian ancestry.[10][11] His descendant, William the Conqueror and his Norman army, would conquer England in 1066 after King Harald III of Norway had failed the same year.

Scotland

Monarchs of the hereditary kingdom

Yngling / Fairhair dynasty

- Harald I Halfdansson

- Eric I Haraldsson

- Haakon I Haraldsson

- Harald II Ericsson

Lade dynasty

- Haakon Sigurdsson

Trygvason dynasty

- Olaf Tryggvason

Lade dynasty (restored)

- Eric Haakonsson and Sweyn Haakonsson

Saint Olaf dynasty

- Olaf II Haraldsson

Lade dynasty (restored, second time)

- Haakon Ericsson

Saint Olaf dynasty (restored)

- Magnus I Olafsson

Hardrada dynasty

- Harald Sigurdsson

- Magnus II Haraldsson

- Olaf III Haraldsson

- Haakon Magnusson

- Magnus III Olafsson

- Olaf IV Magnusson

- Eystein I Magnusson

- Sigurd I Magnusson

- Magnus IV Sigurdsson

Gille dynasty

- Harald IV Magnusson

- Sigurd II Haraldsson

- Inge I Haraldsson

- Eystein II Haraldsson

- Magnus Haraldsson

- Haakon II Sigurdsson

Hardrada dynasty (female line)

- Magnus V Erlingsson

Sverre dynasty

- Sverre I Sigurdsson

- Haakon III Sverresson

- Guttorm Sigurdsson

Gille dynasty (female line)

- Inge II Bårdsson

Sverre dynasty (restored)

- Haakon IV Haakonsson

- Haakon Haakonsson

- Magnus VI Haakonsson

- Eric II Magnusson

- Haakon V Magnusson

Civil war era

The civil war era began in 1130 and ended in 1240. In this period of Norwegian history, some two dozen rival kings and pretenders waged wars to claim the throne. The Civil War period can be divided into three phases: the first phase is sporadic strife between the kings from 1130 to the second phase where there are extensive battles between them from 1160 to 1184 and the final phase in which the Birkebeiners defeat the rest in 1240.

In the absence of formal laws governing claims to rule, men who had proper lineage and wanted to be king came forward and entered into peaceful, if still fraught, agreements to let one man be king, set up temporary lines of succession, take turns ruling, or share power simultaneously. In 1130, with the death of King Sigurd the Crusader, his possible half-brother, Harald Gillekrist, broke an agreement that he and Sigurd had made to pass the throne to Sigurd's only son, the bastard Magnus. Already on bad terms before Sigurd's death, the two men and the factions loyal to them went to war.

In the first decades of the civil wars, alliances shifted and centered on the person of a king or pretender. However, towards the end of the 12th century, two rival parties, the Birkebeiner and the Bagler emerged. In their competition for power, the legitimacy dimension retained its symbolic power, but it was bent to accommodate the parties' pragmatic selection of effective leaders to realize their political aspirations. When they reconciled in 1217, a more ordered and codified governmental system gradually freed Norway from wars to overthrow the lawful monarch. In 1239, Duke Skule Bårdsson became the third pretender to wage war against King Håkon Håkonsson. Duke Skule was defeated in 1240, bringing more than 100 years of civil wars to an end.[13]

Ancient and medieval aristocracy

Aristocracy of Norway refers to modern and medieval aristocracy in Norway . Additionally, there have been economical, political, and military elites that—relating to the main lines of Norway's history—are generally accepted as nominal predecessors of the aforementioned. Since the 16th century, modern aristocracy is known as nobility (Norwegian: adel).

The very first aristocracy in today's Norway appeared during the Bronze Age (1800 BC–500 BC). This bronze aristocracy consisted of several regional elites, whose earliest known existence dates to 1500 BC. Via similar structures in the Iron Age (400 BC–793 AD), these entities would reappear as petty kingdoms before and during the Age of Vikings (793–1066). Beside a chieftain or petty king, each kingdom had its own aristocracy.

Between 872 and 1050, during the so-called unification process, the first national aristocracy began to develop. Regional monarchs and aristocrats who recognised King Harald I as their high king, would normally receive vassalage titles like Earl. Those who refused were defeated or chose to migrate to Iceland, establishing an aristocratic, clan-ruled state there. The subsequent lendman aristocracy in Norway—powerful feudal lords and their families—ruled their respective regions with great autonomy. Their status was by no means equal to that of modern nobles; they were nearly half royal. For example, Ingebjørg Finnsdottir of the Arnmødling dynasty was married to King Malcolm III of Scotland. During the civil war era (1130–1240) the old lendmen were severely weakened, and many disappeared. This aristocracy was ultimately defeated by King Sverre I and the Birchlegs, subsequently being replaced by supporters of Sverre.

Background

Orkney and Shetland

From the 7th century Norwegian farmers began to exodus from Rogaland and Agder to the nearby islands in the North Sea, Orkney and Shetland. These islands had long been undeveloped when the Norwegians arrived, the Picts, a possibly Celtic people who also stayed in mainland Scotland. The Norwegian settlement resulted in the disappearance of the old population, either because they were few and went back to relatives in Scotland, or because they were made slaves (thralls). Most place names on the islands are today of old Norwegian ancestry.

Old legends says that when Harald Fairhair had implemented their piratical expeditions for the national collection, these islands haunt for Vikings ravaged Norway. King Harald awaking West sea and let themselves under Orkney, Shetland and the Hebrides, and got to the Man and harried there. Sagas recounts further that Harald founded Earldom Orkneys, which encompassed all these islands, and he is considered to be the first Norwegian king who reigned over Kingdom of Norway.

However, it is likely that these stories are the saga authors works, to corroborate later Norwegian kings claims over these islands. Some sources find it unlikely that the Norwegian kings had sovereignty in the Hebrides, Man, Orkney and Shetland back to the early 800s.

Sigurd Eysteinsson the first Earl of Orkney, was the brother of Rognvald Eysteinsson Earl of Møre, and the earldom was in this dynasty to 1231. From the first moment the earl had tasks to protect the land and take care of land peace. He had a small lething raft and took a feast of the people.

The islands were Christianized by King Olav Tryggvason in 995. They got themselves a bishop in the 1000s, and from 1152 he heard the Archbishop of Nidaros. The diocese of Orkney was moved to Kirkjuvåg (Kirkwall) and there it were built a cathedral church that stands today. It was the largest cathedral in the archdiocese's second after Nidaros Cathedral, and was consecrated to Saint Magnus Erlendsson, who was killed in 1115.

When the islanders had to put up against the King Sverre Sigurdsson at the Battle of Florvåg outside Bergen in 1194, the king took Shetland from the earl of Orkney and let it directly under the king.

Hebrides

On the Hebrides there were also Norwegian settlement and Norwegian government. It is estimated that the settlement here took to about 800. Harald Fairhair should have inserted an Earl here too. But supremacy in these Viking islands was unstable. Here was the elderly population not taken out. Place names show that the Norwegians lived closest to the islands of Lewis (Ljodhus) and Skye. The Celts had a well known monastery on their sacred island of Iona, and settlers from Norway soon became Christianized.

Isle of Man

The Vikings came to the Isle of Man in the year 798, and eventually became a Norwegian settlement there. The Norwegians lived most of the northern and western edge of the island, while the Celts continued to live on the southern and eastern edge of the island. Many place names reminiscent yet about the Norwegian population.

Man stood sometimes under their own Viking kings or under the Norwegian king of Dublin and was long a kingdom with the Hebrides. Harald Fairhair process hit previously mentioned. Magnus Barefoot's time (1102–1103) heard the kingdom Hebrides and Man to the Kingdom of Norway. From 1153 every new king paid of the Hebrides and Man a bilge fee of 10 gold marks to every new king of Norway.

In 1266 the Hebrides and Man came under Scotland and since came the Isle of Man under England. The Norwegian language of Man died out in the 1400s.

Faroe Islands

An Irishman wrote year 825 that it had lived Irish hermits in the Faroe Islands in a hundred years, but they were lost because of the Norwegian Vikings. Otherwise, there were no population on these islands when Norwegian settlers settled there. The first settler named Grímur Kamban, and the settlement should have been done something before the year 825. Faroe Islands became subject to the Norwegian kingdom in 1035 or something before.

Iceland

Also here lived a few Irish hermits there when the Vikings arrived, and solitaries went his way, as the settlement was made in unpopulated land. Settlement period began with the Ingolv Ørnsson from Sunnfjord took the land in Reykjavík year 874 and lasted until 930. Most settlers came from 890 to 910. It was mostly people who would not stand under Harald Fairhair.

In 1262–1264 Iceland came under the control of the King of Norway, who said Icelanders should provide his tax. Terms were set out in an agreement in 1262, which the Icelanders called Gissur conciliation, after the Earl Gissur Þorvaldsson. Here it says that the King will leave the peace and Icelandic laws, and basically it was so.

Greenland

Erik the Red lived in Jæren, but he and his father were exiled from Norway due to murder, and settled in Iceland. Erik came up in murder cases there too, and was outlawed. Then he went to Greenland, found West Greenland, and made himself familiar with the country. The Book of Settlements suggests that this land was known before Erik, and Snæbjörn galti Hólmsteinsson attempted and failed to colonize eastern Greenland, but Erik was the first permanent settler.

He came back to Iceland, fought with his old opponent, and lost. They were reconciled that Erik had to leave Iceland. That same year, 986, Erik came with a fleet of 14 ships with settlers to Greenland. They settled in the south of West Greenland, in the two villages called Eystribygð (Eastern Settlement) and Vestribygð (Western Settlement).

Our knowledge of Eirik's colonization efforts is derived from writings of the Middle Ages, and from excavations done in modern times. When the settlement was at its largest, was there 16 churches, 2 monasteries and 280 farms in Greenland. The biggest farm was the episcopal estate at Gardar, where the big room was 36 m2 (388 sq ft) and a banquet hall was 130 m2 (1,399 sq ft) and where they had 100 caliper[clarification needed] bound cattle.

The country became Christian in the year 1000, introduced by Leif Eiriksson who was commissioned by King Olaf Tryggvason, and was later a separate diocese. (According to the Saga of Erik the Red, Leif became the first European to discover the North American continent when he was blown off course during his voyage back to Greenland from Norway.) From the sagas[specify] it is clear that Greenland was considered a separate country at this time.

In 1247 a newly appointed bishop came from Norway to Greenland, with orders from King Haakon IV Håkonsson that Greenlanders should not go to the king. In 1261 some farmers came back from Greenland with the message that Greenlanders had committed themselves to paying tax to the king.

Bohuslän

It has been claimed that King Harald Fairhair made it part of the unified Norway in about 872, but contemporary sources give rise to doubt that Harald actually ever held the Viken area properly. The earliest proof of Båhus lands being in Norway's hands is from the 11th century.

As long as Norway was a kingdom of its own, the province prospered, and Båhus castle was one of the key fortresses of the kingdom. When Norway was united with Denmark , the province began its decline in wealth; the area was frequently attacked by Swedish forces as part of the larger border skirmishes. The Norwegian fortress, Båhus, was built to protect this territory. Being a border zone towards the Swedish kingdom, and to a lesser extent against Danish lands in Halland, the Båhus region was disproportionately populated by soldier families.

Jämtland

Snorre Sturlasson writes in Heimskringla about, Ketil Jamt the son of Onund Earl of Sparbu in Trøndelag, he moved east over the ridge to people and livestock, and cleaned up Jämtland. In the saga of Egill Skallagrímsson he writes that the plundering of Harald Fairhair ascended[clarification needed] many people including Jämtland.

According to Snorre, Jämtland had in Harald Fairhair's time an independent position. Under Haakon the Good gave[clarification needed] Jämts in Norway under the King and he promised tax and Hakon put law and land rights for them. This joystick at the front in the 1000s.[clarification needed] In Eric Haakonsson Earl of Lade's, time Jämtland was a part of lens division after the settlement of the great naval Battle of Svolder and Jämtland, Herjedalen, Rana, Båhuslen and Romsdal had fallen on Erik's brother Svein after agreement with the Swedish king, Olof Skötkonung. When Olav demanded tax of Jämtland, he didn't get it.

Jämtland received Christianity from the east as Trøndelag did. According to an inscription in Norwegian from the mid-1000s the country was Christianized by a man named Austmann Gudfastsson. Ecclesiastical heard[clarification needed] country under the Archbishop of Uppsala some time before 1571. Also King Øystein Magnusson (1103–1122) made a claim against the Jämts, that they should go under the king of Norway.

Herjedalen

What about Herjedalen are told that the first settled there, was Herjulv Hornbrjot. He was noticed husband (standard bearer) with King Halfdan the Black, but came in disgrace and went to Svearike. There he became an outlaw and then he settled in Herjedalen, which then layd in Norway. This must have been around the year 850. Herjedalen became Christian in the years 1030 to 1060, and belonged to the diocese of Nidaros.

Finnmark and Lapland

Gjesvær in Nordkapp is mentioned in the Sagas (Heimskringla) as a northern harbor in the Viking Age, especially used by Vikings on the way to Bjarmaland (see Ottar from Hålogaland), and probably also for gathering food in the nearby seabird colony. Coastal areas of Finnmark were colonized by Norwegians beginning in the 10th century, and there are stories describing clashes with the Karelians. Border skirmishes between the Norwegians and Novgorodians continued until 1326, when the Treaty of Novgorod settled the issue.

From the 11th century Olaf III of Norway regarded the borders of Norway as reaching to the White Sea. The first Norwegians started moving to Finnmark in the 13th century. Vardøhus Fortress was erected by Norway in 1306 further east than today's land border by King Haakon V Magnusson, supporting Norwegian land ownership. This is the world's most northern fortress.

Finnmark derives from Finnmork, and is the old Norwegian (Norrøn) description of the land of the Sami people, Sápmi.

Kola (Murmansk)

By the 13th century, a need to formalize the border between the Novgorod Republic and the Scandinavian countries became evident.[14] The Novgorodians, along with the Karelians who came from the south, reached the coast of what now is Pechengsky District and the portion of the coast of Varangerfjord near the Voryema River, which now is a part of Norway.[14] The Sami population was forced to pay tribute.[14] The Norwegians, however, were also attempting to take control of these lands, resulting in armed conflicts.[14] In 1251, a conflict between the Karelians, Novgorodians and the servants of the king of Norway lead to the establishment of a Novgorodian mission in Norway.[14] Also in 1251, the first treaty with Norway was signed in Novgorod regarding the Sami lands and the system of tribute collections, making the Sami people pay tribute to both Novgorod and Norway.[14] By the terms of the treaty, Novgorodians could collect tribute from the Sami as far as Lyngen fjord in the west, while Norwegians could collect tribute on the territory of the whole Kola Peninsula except in the eastern part of Tersky Coast.[14] No state borders were established by the 1251 treaty.[14] At that time there were no permanent Norwegian settlements on the Kola Peninsula, except as late as the 1860s.

The treaty lead to a short period of peace, but the armed conflicts resumed soon thereafter.[14] Chronicles document attacks by the Novgorodians and the Karelians on Finnmark and northern Norway as early as 1271, and continuing well into the 14th century.[14] The official border between the Novgorod lands and the lands of Sweden and Norway was established by the Treaty of Nöteborg on 12 August 1323.[14] The treaty primarily focused on the Karelian Isthmus border and the border north of Lake Ladoga.[14]

Another treaty dealing the matters of the northern borders was the Treaty of Novgorod signed with Norway in 1326, which ended the decades of the Norwegian-Novgorodian border skirmishes in Finnmark.[15] Per the terms of this treaty, Norway relinquished all claims to the Kola Peninsula.[15] A signed agreement regarding the taxation of the Kola Peninsula and Finnmark.[16] No border line was drawn, creating a marchland where both countries held the right to taxation of the Sami people.[17] However, the treaty did not address the situation with the Sami people paying tribute to both Norway and Novgorod, and the practice continued until 1602.[15] While the 1326 treaty did not define the border in detail, it confirmed the 1323 border demarcation, which remained more or less unchanged for the next six hundred years, until 1920.[15]

End of self-rule

After the extinction of the male lines of the perceived Fairhair dynasty in 1319, the throne of Norway passed through matrilineal descent to Magnus VII, who in the same year became elected as king of Sweden too. In 1343 Magnus had to abdicate as King of Norway in favour of his younger son, Haakon VI of Norway. The oldest son, Eric, was explicitly removed from the future line of succession of Norway. Traditionally Norwegian historians have interpreted this clear break with previous successions as stemming from dissatisfaction among the Norwegian nobility with Norway's junior position in the union. However it may also be the result of Magnus' dynastic policies. He had two sons and two kingdoms and might have wished they should inherit one each, rather than start battling over the inheritance. Magnus was at the same time attempting to secure Eric's future election as King of Sweden.

The Black Death of 1349–1351 was a contributing factor to the decline of the Norwegian monarchy as the noble families and population in general were gravely affected. But the most devastating factor for the nobility and the monarchy in Norway was the steep decline in income from their holdings. Many farms were deserted and rents and taxes suffered. This left the Norwegian monarchy weakened in terms of manpower, noble support, defence ability and economic power.[18] The Black Death ended up depleting the population by 65%, from roughly 350,000 to 125,000.[19]

After the death of Haakon VI of Norway in 1380, his son Olav IV of Norway succeeded to both the thrones of Norway and Denmark and also claimed the Kingdom of Sweden, holding its westernmost provinces already. Only after his death at the age of 17 his mother Margaret managed to oust their rival, king Albert, from Sweden, and thus united the three Scandinavian kingdoms in personal union under one crown, in the Kalmar Union. Olav's death extinguished yet one Norwegian male royal line; he was also the last Norwegian king to be born on Norwegian soil for the next 567 years.[18] After the death of Olav IV of Norway in 1387, the closest in line to the succession was the Swedish king Albert of Mecklenburg. However, his succession was politically unacceptable to the Norwegians and Danes. Next in line were the descendants of the Sudreim lineage, legitimate descendants of Haakon V of Norway's illegitimate, but recognized daughter Agnes Haakonardottir, Dame of Borgarsyssel. However, the candidate from this lineage renounced his claim to the throne in favour of Eric of Pomerania, Queen Margaret's favoured candidate. The succession right of this lineage resurfaced in 1448 after the death of King Christopher, but the potential candidate, Sigurd Jonsson, again renounced his candidature (see Sudreim claim). Eric's succession was one in a line of successions which did not precisely follow the laws of inheritance, but excluded one or a few undesirable heirs, leading to Norway formally becoming an elective kingdom in 1450.[20]

Starting with Margaret I of Denmark, the throne of Norway was held by a series of non-Norwegian kings usually perceived as Danish, who variously held the throne to more than one Scandinavian countries, or of all of them.

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ The peak is conventionally understood to begin after the last phase of the unification during the reign of Saint Olav in the 1020s.

- ↑ The empire was under Danish control from the Kalmar Union's beginning in 1397 and forward as the Danish colonial empire, but the possessions such as Iceland, Greenland and Faroe Islands remained Norwegian until the end of the Danish rule of Norway in 1814, when they then officially become a part of the Kingdom of Denmark.

- ↑ As a result of the Norwegian victory in the Battle of Anglesey Sound in 1098 the Welsh considered the Norwegian soldiers as their liberators following Norway's victory against the Normans of England, and Magnus III regarded Anglesey as part of the Kingdom of the Isles and then took the island as a possession of Norway. Since the Norwegians never settled on the island, Anglesey reverted to Welsh control when Gruffudd ap Cynan returned from Ireland the year after in 1099.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Demir, Sores Welat (1 January 2019). Norge & Noreg – Norges Historie / (History of Norway – Book by SWD). SWD Group. ISBN 9788284220246. https://books.google.com/books?id=DX69DwAAQBAJ&dq=nuriki+noreg&pg=PA159. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ↑ Thomas Madden, The New Concise History of the Crusades (Rowman and Littlefield, 2005), pp. 40–43.

- ↑ Bandlien, Bjørn, ed (31 January 2020). "Leiv Eiriksson" (in no). Leiv Eiriksson. https://snl.no/Leiv_Eiriksson. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ↑ The Norwegian Domination and the Norse World, C.1100-c.1400 by Steinar Imsen p. 118-119

- ↑ Imsen, Steinar (11 June 2010). The Norwegian Domination and the Norse World, C.1100-c.1400. Tapir Academic Press. ISBN 9788251925631. https://books.google.com/books?id=EIr7s7SLit0C. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ↑ "When Caithness Became Scottish « Ramscraigs – A Caithness Story". http://ramscraigs.com/?p=465.

- ↑ Oram, Richard (21 February 2011). Domination and Lordship. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748687688. https://books.google.com/books?id=1c9vAAAAQBAJ. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ↑ "The Northern Earldoms - Orkney and Caithness from AD 870 to 1470". https://www.birlinn.co.uk/Northern-Earldoms-The.html.

- ↑ "Vikings in Scotland: An Archaeological Survey" by James Graham-Campbell and Colleen E. Batey (1998) p. 106-108

- ↑ "The Normans" ep. 01 by BBC, written and presented by Professor Robert Bartlett from the University of St. Andrews (2010)

- ↑ https://nbl.snl.no/Rollo_Gange-Rolv_Ragnvaldsson Written for the public Norwegian Encyclopedia SNL, by professor Claus Krag 02.13.09

- ↑ "Scandinavian Scotland" by B.E. Crawford (1987) p. 57 and 65

- ↑ Sawyer, Birgit (2003): "The 'Civil Wars revisited", in Historical Journal, volume 82, s-43-73

- ↑ 14.00 14.01 14.02 14.03 14.04 14.05 14.06 14.07 14.08 14.09 14.10 14.11 Administrative-Territorial Divisions of Murmansk Oblast, p. 17

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Administrative-Territorial Divisions of Murmansk Oblast, p. 18

- ↑ Vassdal, Trond O. (3 August 2012). "Historisk sammendrag vedrørende riksgrensen Norge – Russland" (in no). Norwegian Mapping and Cadastre Authority. http://www.statkart.no/filestore/Landdivisjonen_ny/Fagomrder/dGrenser/grensefiler/Grensenotat_0821012.pdf.

- ↑ Johanson (1999): 15

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "A Short History of Norway". Royal Norwegian Embassy in London. http://www.norway.org.uk/studywork/Norway-For-Young-People/History/Historical-Figures/#.VdELmOLLfK4.

- ↑ Brothen, James A. (1996). "Population Decline and Plague in late medieval Norway" (in fr-FR). Annales de démographie historique 1996 (1): 137–149. doi:10.3406/adh.1996.1915. PMID 11619268. http://www.persee.fr/doc/adh_0066-2062_1996_num_1996_1_1915. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ↑ Hødnebø, Finn, ed (1974). Kulturhistorisk leksikon for nordisk middelalder, bind XVIII. Gyldendal norsk forlag. p. 691.

|

KSF

KSF