Prehistoric East Africa

Topic: History

From HandWiki - Reading time: 18 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 18 min

The prehistory of East Africa spans from the earliest human presence in the region until the emergence of the Iron Age in East Africa. Between 1,600,000 BP and 1,500,000 BP, the Homo ergaster known as Nariokotome Boy resided near Nariokotome River, Kenya.[1] Modern humans, who left behind remains, resided at Omo Kibish in 233,000 BP.[2] Afro-Asiatic speakers and Nilo-Saharan speakers expanded in East Africa, resulting in transformation of food systems of East Africa.[3] Prehistoric West Africans may have diverged into distinct ancestral groups of modern West Africans and Bantu-speaking peoples in Cameroon, and, subsequently, around 5000 BP, the Bantu-speaking peoples migrated into other parts of Sub-Saharan Africa (e.g., Central African Republic, African Great Lakes, South Africa ).[4]

Early Stone Age

Between 1,600,000 BP and 1,500,000 BP, the Homo ergaster known as Nariokotome Boy resided near Nariokotome River, Kenya.[1]

Middle Stone Age

Modern humans, who left behind remains, resided at Omo Kibish in 233,000 BP.[2]

In 150,000 BP, Africans (e.g., Central Africans, East Africans) bearing haplogroup L1 diverged.[5]

In 130,000 BP, Africans bearing haplogroup L5 diverged in East Africa.[5]

Between 130,000 BP and 75,000 BP, behavioral modernity emerged among Southern Africans and long-term interactions between the regions of Southern Africa and Eastern Africa became established.[5]

Between 75,000 BP and 60,000 BP, Africans bearing haplogroup L3 emerged in East Africa and eventually migrated into and became present in modern West Africans, Central Africans, and non-Africans.[5] As the largest migration since the Out of Africa migration, migration from Sub-Saharan Africa toward the North Africa occurred, by West Africans, Central Africans, and East Africans, resulting in migrations into Europe and Asia; consequently, Sub-Saharan African mitochondrial DNA was introduced into Europe and Asia.[5]

In 78,300 BP, amid the Middle Stone Age, a two and half to three year old human child was buried at Panga ya Saidi, in Kenya.[6]

Later Stone Age

At Mlambalasi rockshelter, in Tanzania, an individual, dated between 20,345 BP and 17,025 BP, carried undetermined haplogroups.[7]

In 19,000 BP, Africans, bearing haplogroup E1b1a-V38, likely traversed across the Sahara, from east to west.[4]

Between 15,000 BP and 7000 BP, 86% of Sub-Saharan African mitochondrial DNA was introduced into Southwest Asia by East Africans, largely in the region of Arabia, which constitute 50% of Sub-Saharan African mitochondrial DNA in modern Southwest Asia.[5] In the modern period, 68% of Sub-Saharan African mitochondrial DNA was introduced by East Africans and 22% was introduced by West Africans, which constitutes 50% of Sub-Saharan African mitochondrial DNA in modern Southwest Asia.[5]

In 13,000 BP, Nubians, who were found to be morphologically different from newer Nubian populations and morphologically similar to Sub-Saharan Africans (e.g., Kerma, modern Eastern Africans, modern Western Africans), resided in tropical Jebel Sahaba.[8]

During the early period of the Holocene, 50% of Sub-Saharan African mitochondrial DNA was introduced into North Africa by West Africans and the other 50% was introduced by East Africans.[5] During the modern period, a greater number of West Africans introduced Sub-Saharan African mitochondrial DNA into North Africa than East Africans.[5]

Amid the Holocene, including the Holocene Climate Optimum in 8000 BP, Africans bearing haplogroup L2 spread within West Africa and Africans bearing haplogroup L3 spread within East Africa.[5]

Pastoral Neolithic

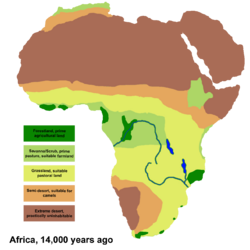

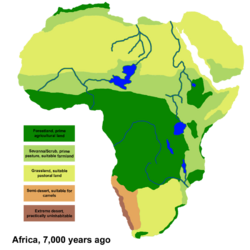

After the Bubaline Period, Kel Essuf Period, and Round Head Period of the Central Sahara, the Pastoral Period followed.[9] In East Africa, the beginning of the Pastoral Neolithic follows the Late Stone Age around 5000 BP.[10] The earliest instances of food production in East Africa are found in Kenya and Tanzania.[11] The earliest Pastoral Neolithic sites are in the Lake Turkana region from around 5000 BP.[11] Predating the introduction of imported livestock, African pastoralists kept domestic livestock but did not keep the lifestyles characteristic of modern pastoralists; this is shown by the lack of bones from domesticated animals and an abundance of bones from undomesticated animals at early Pastoral Neolithic sites.[11] These preliminary herding cultures are characteristic of the Pastoral Neolithic and generally lack stationary agricultural practices and metal use.[12] The exact introductory timeline of pastoralism to eastern Africa is not completely known.[13] A considerable amount of evidence supports the case of there being two major expansions (associated with the spread of Afro-Asiatic and Nilo-Saharan languages) in eastern Africa which transformed the food systems of the region.[3] Between 8000 BP and 2000 BP, Saharan herders migrated into Eastern Africa, and brought along with them their monumental Saharan burial traditions.[14] Genetic evidence shows that lactase persistence developed in East African populations between 7000 BP and 3000 BP, which is consistent with existing evidence for the introduction of livestock.[15] The shift from hunting-gathering to herding developed gradually, over thousands of years, during the Pastoral Neolithic.[15] The Pastoral Neolithic of East Africa is one of a few in world history where herding significantly preceded agricultural food production.[15] The major transition from predominantly hunter-gatherer economies to predominantly herding economies may have occurred around 3000 BP.[11] There are limited remains of domesticated animals at sites that predate 3000 BP.[11] For example, at the Enkapune Ya Muto rock shelter site of central Kenya, among evidence of mostly wild fauna, there are few caprine (goat/sheep) teeth dated to around 4400 BP.[15] The length of time between the initial introduction of domesticates and their full adoption is thought to have occurred between the cultural separation of immigrant populations and indigenous populations in the region.[15] Additionally, paleoclimatic evidence from Lake Naivasha, Kenya suggests that rain patterns may not have been favorable for dairy pastoralism until around 3000 BP.[11] After 3000 BP, the majority of fauna found at Pastoral Neolithic sites are from domesticated animals rather than undomesticated animals.[11] By this time, many communities were exclusively stock-keeping and herding.[15]

The genomes of Africans commonly found to undergo adaptation are regulatory DNA, and many cases of adaptation found among Africans relate to diet, physiology, and evolutionary pressures from pathogens.[16] Throughout Sub-Saharan Africa, genetic adaptation (e.g., rs334 mutation, Duffy blood group, increased rates of G6PD deficiency, sickle cell disease) to malaria has been found among Sub-Saharan Africans, which may have initially developed in 7300 BP.[16] Sub-Saharan Africans have more than 90% of the Duffy-null genotype.[17] In the highlands of Ethiopia, genetic adaptation (e.g., rs10803083, an SNP associated with the rate and function of hemoglobin; BHLHE41, a gene associated with circadian rhythm and hypoxia response; EGNL1, a gene strongly associated with oxygen homeostasis in mammals) to hypoxia and low atmospheric pressure has been found among the Amhara people, which may have developed within the past 5000 years.[16] In Tanzania, genetic adaptation (e.g., greater amount of amylase genes than in African populations that consume low-starch foods) has been found in the Hadza people due to a food diet that especially includes consumption of tubers.[16]

Preceded by assumed earlier sites in the Eastern Sahara, tumuli with megalithic monuments developed as early as 4700 BCE in the Saharan region of Niger.[18] These megalithic monuments in the Saharan region of Niger and the Eastern Sahara may have served as antecedents for the mastabas and pyramids of ancient Egypt.[18] During Predynastic Egypt, tumuli were present at various locations (e.g., Naqada, Helwan).[18]

The prehistoric tradition of monarchic tumuli-building is shared by both the West African Sahel and the Middle Nile regions.[19] Ancient Egyptian pyramids of the early dynastic period and Meroitic Kush pyramids are recognized by Faraji (2022) as part of and derived from an earlier architectural “Sudanic-Sahelian” tradition of monarchic tumuli, which are characterized as “earthen pyramids” or “proto-pyramids.”[19] Faraji (2022) characterized Nobadia as the “last pharaonic culture of the Nile Valley” and described mound tumuli as being “the first architectural symbol of the sovereign’s return and reunification with the primordial mound upon his death.”[19] Faraji (2022) indicates that there may have been a cultural expectation of “postmortem resurrection” associated with tumuli in the funerary traditions of the West African Sahel (e.g., northern Ghana, northern Nigeria, Mali) and Nile Valley (e.g., Ballana, Qustul, Kerma, Kush).[19] Based on artifacts found in the tumuli from West Africa and Nubia, there may have been “a highly developed corporate ritual in which the family members of the deceased brought various items as offerings and tribute to the ancestors” buried in the tumuli and the tumuli may have “served as immense shrines of spiritual power for the populace to ritualize and remember their connection to the ancestral lineage as consecrated in the royal tomb.”[19]

Between the 8th millennia BCE and the 4th millennia BCE, riverine farmers and savanna herders traversed the interconnected region of the Middle Nile Valley.[19] In the Saharan-Sahelian and Middle Nile Valley regions, dotted wavy line and wavy line pottery, which was produced between the 8th millennia BCE and the 4th millennia BCE (late Neolithic and early Bronze Age), preceded the emergence of monarchic tumuli; the spread of the pottery spanned from the savanna region to the eastern Saharan region, and from Mauritania to the Red Sea, which supports the conclusions of trade between the regions and their interconnectedness.[19] Wavy-line pottery developed six ceramic subvariants and dotted wavy-line pottery developed three ceramic subvariants; the locations for the earliest development of both 8th millennium BCE potteries were at Sagai and Sarurab in Sudan.[19] Wavy-line pottery spread throughout multiple locations (e.g., mostly in Central Nile; some in Hoggar Mountains, southern Algeria, Delibo Cave, Chad, Jebel Eghei, Chad, Tibesti, Chad, and Adrar Madet, Niger) in Africa.[19] Dotted wavy-line pottery spread throughout multiple locations (e.g., Ennedi Plateau, Niger Plateau, and Wadi Howar of Saharan-Sahelian region, interconnecting the regions of the Middle Nile River, Lake Chad, and Benue-Niger River) in Africa as well.[19] Both potteries also spread along a north-to-west regional axis (e.g., Wadi Howar, Ennedi Plateau, Chad, Jebel Uweinat, Gilf Kebir, Egypt) near the Saharan regions of Sudan and Egypt.[19] The tumuli from the kingdom of Kerma serve as a regional intermediary between the regions of the Nile River and the Niger River.[19]

The “Classical Sudanese” monarchic tumuli-building tradition, which lasted in Sudan (e.g., Kerma, Makuria, Meroe, Napata, Nobadia) until the early period of the 6th century CE as well as in West Africa and Central Africa until the 14th century CE, notably preceded the spread of Islam into the West African and Sahelian regions of Africa.[19] According to al-Bakrī, “the construction of tumuli and the accompanying rituals was a religious endeavor that emanated from the other elements” that he described, such as “sorcerers, sacred groves, idols, offerings to the dead, and the “tombs of their kings.””[19] Faraji (2022) indicated that the early dynastic period of ancient Egypt, Kerma of Kush, and the Nobadian culture of Ballana were similar to al-Bakrī’s descriptions of the Mande tumuli practices of ancient Ghana.[19] A characteristic of divine kingship sometimes includes monarchic funerary practices (e.g., Ancient Egyptian funerary practices).[19] In the lake region of Niger, two human burial sites included funerary rooms with graves that contain various bones (e.g., human, animal) and items (e.g., beads, ornaments, weapons).[19] In the Inland Niger Delta, 11th century CE and 15th century CE tumuli at El Oualedji and Koï Gourrey contained various bones (e.g., human, horse), human items (e.g., beads, bracelets, rings), and animal items (e.g., bells, harnesses, plaques).[19] Cultural similarities were also found with a Malinke king of Gambia, who along with his senior queen, human subjects within his kingdom, and his weapons, were buried in his home under a large mound the size of the house, as described by V. Fernandes.[19] Levtzion also acknowledged the cultural similarities between the monarchic tumuli-building traditions and practices (e.g., monumental Senegambian megaliths) of West Africa, such as Senegambia, Inland Niger Delta, and Mali, and the Nile Valley; these monarchic tumuli-building practices span the Sudanian savanna as manifestations of a trans-Sahelian common culture and heritage.[19]

From the 5th millennium BCE to the 14th century CE, earthen and stone tumuli were developed between Senegambia and Chad.[19] Among 10,000 burial mounds in Senegambia, 3,000 megalithic burial mounds in Senegambia were constructed between 200 BCE and 100 CE, and 7,000 earthen burial mounds in Senegal were constructed in the 2nd millennium CE.[19] Between 1st century CE and 15th century CE, megalithic monuments without tumuli were constructed.[19] Megalithic and earthen Senegambian tumuli, which may have been constructed by the Wolof people (Serer people) or Sosse people (Mande peoples).[19] Sudanese tumuli (e.g., Kerma, C-Group), which date to the mid-3rd millennium BCE, share cultural similarities with Senegambian tumuli.[19] Between the 6th century CE and 14th century CE, stone tumuli circles, which at a single site usually encircle a burial site of half-meter that is covered by a burial mound, were constructed in Komaland; the precursors for this 3rd millennium BCE tumuli style of Komaland, Ghana and Senegambia are regarded by Faraji (2022) to be Kerma Kush and the A-Group culture of ancient Nubia.[19] While the stele-circled burial mounds of C-Group culture of Nubia are regarded as precursors for the megalithic burial mounds of Senegambia, Kerma tumuli are regarded as precursors for the stone tumuli circles of Komaland.[19] Based on a founding narrative of the Hausa people, Faraji (2022) concludes the possibility of the “pre-Islamic rulers of Hausaland” being a “dynasty of female monarchs reminiscent of the kandake of Meroitic Kush.”[19] The tumuli of Durbi Takusheyi, which have been dated between the 13th century CE and the 16th century CE, may have connection to tumuli from Ballana and Makuria.[19] Tumuli have also been found at Kissi, in Burkina Faso, and at Daima, in Nigeria.[19]

At Kisese II rockshelter, in Tanzania, an individual, dated between 7240 BP and 6985 BP, carried haplogroups B2b1a~ and L5b2.[7]

Amid the Holocene, around 7100 BP, six individuals were buried.[20]

From West Africa, Bantu-speaking peoples migrated, along with their ceramics, into the other areas of Sub-Saharan Africa.[21] The Kalundu ceramic type may have spread into Southeastern Africa.[21] Additionally, the Eastern African Urewe ceramic type of Lake Victoria may have spread, via African shores near the Indian Ocean, as the Kwale ceramic type, and spread, via Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Malawi, as the Nkope ceramic type.[21] From the region of Kenya and Tanzania to South Africa , eastern Bantu-speaking Africans constitute a north to south genetic cline; additionally, from eastern Africa to toward southern Africa, evidence of genetic homogeneity is indicative of a serial founder effect and admixture events having occurred between Bantu-speaking Africans and other African populations by the time the Bantu migration had spanned into South Africa.[16] Though some may have been created later, the earlier red finger-painted rock art may have been created between 6000 BP and 1800 BP, to the south of Kei River and Orange River by Khoisan hunter-gatherer-herders, in Malawi and Zambia by considerably dark-skinned, occasionally bearded, bow-and-arrow-wielding Akafula hunter-gatherers who resided in Malawi until the 19th century CE, and in Transvaal by the Vhangona people.[22] Bantu-speaking farmers, or their Proto-Bantu progenitors, created the later white finger-painted rock art in some areas of Tanzania, Malawi, Angola, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, as well as in the northern regions of Mozambique, Botswana, and Transvaal.[22] The Transvaal (e.g., Soutpansberg, Waterberg) rock art was specifically created by Sotho-speakers (e.g., Birwa, Koni, Tlokwa) and Venda people.[22] Concentric circles, stylized humans, stylized animals, ox-wagons, saurian figures, Depictions of crocodiles and snakes were included in the white finger-painted rock art tradition, both of which were associated with rainmaking and, crocodiles in particular, were also associated with fertility.[22] The white finger-painted rock art may have been created for reasons relating to initiation rites and puberty rituals.[22] Depictions from the rock art tradition of Bantu-speaking farmers have been found on divination-related items (e.g., drums, initiation figurines, initiation masks); fertility terracotta masks from Transvaal have been dated to the 1st millennium CE.[22] Along with Iron Age archaeological sites from the 1st millennium CE, this indicates that white finger-painted rock art tradition may have been spanned from the Early Iron Age to the Later Iron Age.[22]

At Mota, in Ethiopia, an individual, estimated to date to the 5th millennium BP, carried haplogroups E1b1 and L3x2a.[23][24] The individual of Mota is genetically related to groups residing near the region of Mota, and in particular, are considerably genetically related to the Ari people.[25][26]

Finger millet is originally native to the highlands of East Africa and was domesticated before the third millennium BCE in Uganda and Ethiopia. Its cultivation had spread to South India by 1800 BCE.[27]

In the uplands of Nakfa, there is painted rock art (e.g., petroglyphs) in Karora depicting symbolic representations, men, and animals (e.g., horses, camels, antelopes, goats, sheep, cattle), which has been dated to the 2nd millennium BCE.[28][29]

In 2nd millennium BCE, Namoratunga megaliths were constructed as burials the eastern Turkana region of northwestern Kenya.[30]

At Kakapel, in Kenya, there were three individuals, one dated to the Later Stone Age (3900 BP) and two dated to the Later Iron Age (300 BP, 900 BP); one carried haplogroups CT (CT-M168, CT-M5695) and L3i1, another carried haplogroup L2a1f, and the last carried haplogroup L2a5.[31][32] At Munsa, in Uganda, an individual, dated to the Later Iron Age (500 BP), carried haplogroup L3b1a1.[31][32]

At Nyarindi Rockshelter, in Kenya, there were two individuals, dated to the Later Stone Age (3500 BP); one carried haplogroup L4b2a and another carried haplogroup E (E-M96, E-P162).[31][32] At White Rock Point, in Homa Bay County, Kenya, there were two foragers of the Later Stone Age; one carried haplogroups BT (xCT), likely B, and L2a4, and another probably carried haplogroup L0a2.[33][34] At Jawuoyo Rockshelter, in Kisumu County, Kenya, a forager of the Later Stone Age carried haplogroups E1b1b1a1b2/E-V22 and L4b2a2c.[33][34]

At Lukenya Hill, in Kenya, there were two individuals, dated to the Pastoral Neolithic (3500 BP); one carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b (E-M293, E-CTS10880) and L4b2a2b, and another carried haplogroup L0f1.[31][32]

At Luxmanda, Tanzania, an individual, estimated to date between 3141 BP and 2890 BP, carried haplogroup L2a1.[35]

In the Ethiopian Highlands of Harar, the earliest construction of megaliths occurred.[30] From this region and its megalith-building tradition (e.g., dolmens, tumuli with burial chambers organized in cemeteries), the subsequent traditions in other areas of Ethiopia likely developed.[30] In the late 1st millennium BCE, the urban civilization of Axum developed a megalithic stelae-building tradition, which commemorated Axumite royalty and elites, that persisted until the Christian period of Axum.[30] In the Sidamo Province, the megalithic monoliths of the stelae-building cultural tradition were utilized as tombstones in cemeteries (e.g., Arussi, Konso, Sedene, Tiya, Tuto Felo), and have engraved anthropomorphic features (e.g., swords, masks), phallic form, and some of that served as markers of territory.[30] Sidamo Province has the most megaliths in Ethiopia.[30]

At Cole's Burial, in Nakuru County, Kenya, a pastoralist of the Pastoral Neolithic carried haplogroups E1b1b1a1a1b1/E-CTS3282 and L3i2.[33][34]

At Rigo Cave, in Nakuru County, Kenya, there were three pastoralists of the Pastoral Neolithic/Elmenteitan, one carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b2a1/E-M293 and L3f, another carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b2/E-V1486, likely E-M293, and probably M1a1b, and the last carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b2a1/E-M293 and L4b2a2c.[33][34]

At Naishi Rockshelter, in Nakuru County, Kenya, there two pastoralists of the Pastoral Neolithic; one carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b/E-V1515, likely E-M293, and L3x1a, and another carried haplogroups A1b (xA1b1b2a)/A-P108 and L0a2d.[33][34]

At Keringet Cave, in Nakuru County, Kenya, a pastoralist of the Pastoral Neolithic carried haplogroups A1b1b2/A-L427 and L4b2a1, and another pastoralist of the Pastoral Neolithic/Elmenteitan carried haplogroup K1a.[33][34]

At Naivasha Burial Site, in Nakuru County, Kenya, there were five pastoralists of the Pastoral Neolithic; one carried haplogroup L4b2a2b, another carried haplogroups xBT, likely A, and M1a1b, another carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b2a1/E-M293 and L3h1a1, another carried haplogroups A1b1b2b/A-M13 and L4a1, and the last carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b2a1/E-M293 and L3x1a.[33][34]

At Njoro River Cave II, in Nakuru County, Kenya, a pastoralist of the Pastoral Neolithic carried haplogroup L3h1a2a1.[33][34]

At Egerton Cave, in Nakuru County, Kenya, a pastoralist of the Pastoral Neolithic/Elmenteitan carried haplogroup L0a1d.[33][34]

At Ol Kalou, in Nyandarua County, Kenya, a pastoralist of the Pastoral Neolithic carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b2a1/E-M293 and L3d1d.[33][34]

At Hyrax Hill, in Kenya, an individual, dated to the Pastoral Neolithic (2300 BP), carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b (E-M293, E-M293) and L5a1b.[31][32]

At Molo Cave, in Kenya, there were two individuals, dated to the Pastoral Neolithic (1500 BP); while one had haplogroups that went undetermined, another carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b (E-M293, E-M293) and L3h1a2a1.[31][32]

At Makangale Cave, on Pemba Island, Tanzania, an individual, estimated to date between 1421 BP and 1307 BP, carried haplogroup L0a.[35]

At Kuumbi Cave, in Zanzibar, Tanzania, an individual, estimated to date between 1370 BP and 1303 BP, carried haplogroup L4b2a2c.[35]

At Kisima Farm/Porcupine Cave, in Laikipia County, Kenya, there were two pastoralists of the Pastoral Neolithic; one carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b2a1/E-M293 and M1a1, and another carried haplogroup M1a1f.[33][34]

At Prettejohn’s Gully, in Nakuru County, Kenya, there were two pastoralists of the early pastoral period; one carried haplogroups E2 (xE2b)/E-M75 and K1a, and another carried haplogroup L3f1b.[33][34]

At Gishimangeda Cave, in Karatu District, Tanzania, there were eleven pastoralists of the Pastoral Neolithic; one carried haplogroups E1b1b1a1b2/E-V22 and HV1b1, another carried haplogroup L0a, another carried haplogroup L3x1, another carried haplogroup L4b2a2b, another carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b2a1/E-M293 and L3i2, another carried haplogroup L3h1a2a1, another carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b2/E-V1486, likely E-M293 and L0f2a1, and another carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b2/E-V1486, likely E-M293, and T2+150; while most of the haplogroups among three pastoralists went undetermined, one was determined to carry haplogroup BT, likely B.[33][34]

At Kokurmatakore, in Marsabit County, Kenya, a pastoralist of the Pastoral Iron Age carried haplogroups E1b1b1/E-M35 and L3a2a.[33][34] At Kisima Farm/C4, in Laikipia County, Kenya, a pastoralist of the Pastoral Iron Age, carried haplogroups E2 (xE2b)/E-M75 and L3h1a1.[33][34] At Laikipia District Burial, in Laikipia County, Kenya, a pastoralist of the Pastoral Iron Age carried haplogroup L0a1c1.[33][34] At Ilkek Mounds, in Nakuru County, Kenya, a pastoralist of the Pastoral Iron Age carried haplogroups E2 (xE2b)/E-M75 and L0f2a.[33][34] At Kasiole 2, in Narok County, Kenya, a pastoralist of the Pastoral Iron Age carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b/E-V1515, likely E-M293, and L3h1a2a1.[33][34] At Emurua Ole Polos, in Narok County, Kenya, a pastoralist of the Pastoral Iron Age carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b2a1/E-M293 and L3h1a2a1.[33][34] At Deloraine Farm, in Nakuru County, Kenya, an iron metallurgist of the Iron Age carried haplogroups E1b1a1a1a1a/E-M58 and L5b1.[33][34]

At Makangale Cave, on Pemba Island, Tanzania, an individual, estimated to date between 639 BP and 544 BP, carried haplogroup L2a1a2.[35]

At Panga ya Saidi, in Kenya, an individual, estimated to date between 496 BP and 322 BP, carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2 and L4b2a2.[35]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "No skeletal dysplasia in the Nariokotome boy KNM-WT 15000 (Homo erectus) – A reassessment of congenital pathologies of the vertebral column". American Journal of Physical Anthropology 150 (3): 365–374. 2013. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22211. PMID 23283736. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ajpa.22211.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Vidal, Celine M. et al. (Jan 2022). "Age of the oldest known Homo sapiens from eastern Africa". Nature 601 (7894): 579–583. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04275-8. PMID 35022610. Bibcode: 2022Natur.601..579V.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Prendergast, Mary E.; Lipson, Mark; Sawchuk, Elizabeth A.; Olalde, Iñigo; Ogola, Christine A.; Rohland, Nadin; Sirak, Kendra A.; Adamski, Nicole et al. (2019-07-05). "Ancient DNA reveals a multistep spread of the first herders into sub-Saharan Africa" (in en). Science 365 (6448): eaaw6275. doi:10.1126/science.aaw6275. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 31147405. Bibcode: 2019Sci...365.6275P.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Shriner, Daniel; Rotimi, Charles N. (2018). "Whole-Genome-Sequence-Based Haplotypes Reveal Single Origin of the Sickle Allele during the Holocene Wet Phase". American Journal of Human Genetics 102 (4): 547–556. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.02.003. OCLC 8158698745. PMID 29526279.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 Sá, Luísa (16 August 2022). "Phylogeography of Sub-Saharan Mitochondrial Lineages Outside Africa Highlights the Roles of the Holocene Climate Changes and the Atlantic Slave Trade". International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23 (16): 9219. doi:10.3390/ijms23169219. ISSN 1661-6596. OCLC 9627558751. PMID 36012483.

- ↑ Martinón-Torres, María (5 May 2021). "Earliest known human burial in Africa". Nature 593 (7857): 95–100. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03457-8. ISSN 0028-0836. OCLC 9023721985. PMID 33953416. Bibcode: 2021Natur.593...95M. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-03457-8.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Lipson, Mark (23 February 2022). "Extended Data Table 1 Ancient individuals analysed in this study: Ancient DNA and deep population structure in sub-Saharan African foragers". Nature 603 (7900): 290–296. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04430-9. ISSN 0028-0836. OCLC 9437356581. PMID 35197631. Bibcode: 2022Natur.603..290L.

- ↑ Holliday, T. W. (July 2015). "Population Affinities of the Jebel Sahaba Skeletal Sample: Limb Proportion Evidence". International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 25 (4): 466–476. doi:10.1002/OA.2315. ISSN 1047-482X. OCLC 5857432312. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/oa.2315.

- ↑ Soukopova, Jitka (August 2017). "Central Saharan rock art: Considering the kettles and cupules". Journal of Arid Environments 143: 10–14. doi:10.1016/J.JARIDENV.2016.12.011. ISSN 0140-1963. OCLC 7044514678. Bibcode: 2017JArEn.143...10S. https://www.academia.edu/33092285.

- ↑ Grillo, Katherine M.; Prendergast, Mary E.; Contreras, Daniel A.; Fitton, Tom; Gidna, Agness O.; Goldstein, Steven T.; Knisley, Matthew C.; Langley, Michelle C. et al. (2018-02-17). "Pastoral Neolithic Settlement at Luxmanda, Tanzania". Journal of Field Archaeology 43 (2): 102–120. doi:10.1080/00934690.2018.1431476. ISSN 0093-4690. https://doi.org/10.1080/00934690.2018.1431476.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 Bower, John (1991). "The Pastoral Neolithic of East Africa". Journal of World Prehistory 5 (1): 49–82. doi:10.1007/BF00974732. ISSN 0892-7537. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25800592.

- ↑ Bower, John (1991-03-01). "The Pastoral Neolithic of East Africa" (in en). Journal of World Prehistory 5 (1): 49–82. doi:10.1007/BF00974732. ISSN 0892-7537.

- ↑ Prendergast, Mary E.; Lipson, Mark; Sawchuk, Elizabeth A.; Olalde, Iñigo; Ogola, Christine A.; Rohland, Nadin; Sirak, Kendra A.; Adamski, Nicole et al. (2019-07-05). "Ancient DNA reveals a multistep spread of the first herders into sub-Saharan Africa" (in en). Science 365 (6448): eaaw6275. doi:10.1126/science.aaw6275. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 31147405. Bibcode: 2019Sci...365.6275P.

- ↑ Sawchuk, Elizabeth A. (September 2018). "Cemeteries on a moving frontier: Mortuary practices and the spread of pastoralism from the Sahara into eastern Africa". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 51: 187–205. doi:10.1016/J.JAA.2018.08.001. ISSN 0278-4165. OCLC 7807446987. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S027841651730123X.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 Lane, Paul J. (2013-07-04). "The Archaeology of Pastoralism and Stock-Keeping in East Africa". in Mitchell, Peter; Lane, Paul J (in en). doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199569885.001.0001. https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199569885.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199569885-e-40.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Pfennig, Aaron (March 29, 2023). "Evolutionary Genetics and Admixture in African Populations". Genome Biology and Evolution 15 (4): evad054. doi:10.1093/gbe/evad054. OCLC 9817135458. PMID 36987563. PMC 10118306. https://academic.oup.com/gbe/article/15/4/evad054/7092825.

- ↑ Wonkam, Ambroise; Adeyemo, Adebowale (March 8, 2023). "Leveraging our common African origins to understand human evolution and health". Cell Genomics 3 (3): 100278. doi:10.1016/j.xgen.2023.100278. PMID 36950382. PMC 10025516. https://www.cell.com/cell-genomics/pdf/S2666-979X(23)00038-1.pdf.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Hassan, F.A. (2002). "Palaeoclimate, Food And Culture Change In Africa: An Overview". Droughts, Food And Culture: Ecological Change And Food Security In Africa's Later Prehistory. Springer. pp. 11–26. doi:10.1007/0-306-47547-2_2. ISBN 0-306-46755-0. OCLC 51874863. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/0-306-47547-2_2.

- ↑ 19.00 19.01 19.02 19.03 19.04 19.05 19.06 19.07 19.08 19.09 19.10 19.11 19.12 19.13 19.14 19.15 19.16 19.17 19.18 19.19 19.20 19.21 19.22 19.23 19.24 19.25 19.26 19.27 19.28 19.29 Faraji, Salim (September 2022). "Rediscovering the Links between the Earthen Pyramids of West Africa and Ancient Nubia: Restoring William Leo Hansberry’s Vision of Ancient Kush and Sudanic Africa". Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 35: 49–67. ISBN 9780964995864. OCLC 1343909954. https://www.academia.edu/99787064.

- ↑ Laird, Myra F. (January 2021). "Human burials at the Kisese II rockshelter, Tanzania". American Journal of Physical Anthropology 175 (1): 187–200. doi:10.1002/ajpa.24253. ISSN 0002-9483. OCLC 8995410614. PMID 33615431.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Vicente, Mario (2020). Demographic History and Adaptation in African Populations. Acta Universitatis Upsaliens Uppsala. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-91-513-0889-0. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1412382/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 22.6 Prins, Frans E.; Hall, Sian (1994). "Expressions of fertility, in the rock art of Bantu-speaking agriculturists". African Archaeological Review 12: 173–175, 197–198. doi:10.1007/BF01953042. ISSN 0263-0338. OCLC 5547024308. http://bezhoek.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Article-on-Rock-Art.pdf.

- ↑ Llorente, M. Gallego (November 2015). "Ancient Ethiopian genome reveals extensive Eurasian admixture throughout the African continent". Science 350 (6262): 820–822. doi:10.1126/science.aad2879. PMID 26449472. Bibcode: 2015Sci...350..820L. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aad2879.

- ↑ Llorente, M. Gallego (13 November 2015). "Supplementary Materials for Ancient Ethiopian genome reveals extensive Eurasian admixture in Eastern Africa". Science 350 (6262): 820–822. doi:10.1126/science.aad2879. PMID 26449472. Bibcode: 2015Sci...350..820L. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aad2879.

- ↑ Hellenthal, G; Bird, N; Morris, S (April 2021). "Structure and ancestry patterns of Ethiopians in genome-wide autosomal DNA". Human Molecular Genetics 30 (R1): R42–R48. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddab019. ISSN 0964-6906. OCLC 9356326828. PMID 33547782.

- ↑ Pagani, Luca (13 July 2012). "Ethiopian genetic diversity reveals linguistic stratification and complex influences on the Ethiopian gene pool". American Journal of Human Genetics 91 (1): 83–96. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.05.015. ISSN 1537-6605. PMID 22726845.

- ↑ Engels, J. M. M.; Hawkes, J. G.; Hawkes, John Gregory; Worede, M. (1991-03-21). Plant Genetic Resources of Ethiopia. ISBN 9780521384568. https://books.google.com/books?id=WKj__YqTU4AC&q=finger+millet+domesticated+ethiopia&pg=PA162.

- ↑ Rao, Sadasivuni Krishna (August 2014). "Ecological Perspective of Rock Art of Eritrea in East Africa". Asian Journal of Humanities and Social Studies 2 (4): 548. ISSN 2321-2799. OCLC 958715841. https://ajouronline.com/index.php/AJHSS/article/download/1419/799.

- ↑ Hagos, Tekle (June 2011). The Ethiopian Rock Arts: The Fragile Resources. Galda Verlag. p. 104. ISBN 9783941267534. OCLC 987204326. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281279107.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 30.5 Holl, Augustin F.C. (2020). "Megaliths in Tropical Africa: Social Dynamics and Mortuary Practices in Ancient Senegambia (ca. 1350 BCE -1500 CE)". International Journal of Modern Anthropology 2 (15): 364–368, 372, 405. doi:10.4314/IJMA.V2I15.1. ISSN 1737-7374. OCLC 9053151421. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350557762.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 31.5 Wang, Ke (June 2020). "Ancient genomes reveal complex patterns of population movement, interaction, and replacement in sub-Saharan Africa". Science Advances 6 (24): eaaz0183. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaz0183. OCLC 9579954867. PMID 32582847. Bibcode: 2020SciA....6..183W.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 32.5 Wang, Ke (June 2020). "Supplementary Materials for Ancient genomes reveal complex patterns of population movement, interaction, and replacement in sub-Saharan Africa". Science Advances 6 (24): eaaz0183. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaz0183. OCLC 9579954867. PMID 32582847. PMC 7292641. Bibcode: 2020SciA....6..183W. https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/suppl/2020/06/08/6.24.eaaz0183.DC1/aaz0183_SM.pdf.

- ↑ 33.00 33.01 33.02 33.03 33.04 33.05 33.06 33.07 33.08 33.09 33.10 33.11 33.12 33.13 33.14 33.15 33.16 33.17 33.18 33.19 Prendergast, Mary E. (July 2019). "Ancient DNA reveals a multistep spread of the first herders into sub-Saharan Africa". Science 365 (6448). doi:10.1126/science.aaw6275. OCLC 8168339433. PMID 31147405. Bibcode: 2019Sci...365.6275P.

- ↑ 34.00 34.01 34.02 34.03 34.04 34.05 34.06 34.07 34.08 34.09 34.10 34.11 34.12 34.13 34.14 34.15 34.16 34.17 34.18 34.19 Prendergast, Mary E. (5 July 2019). "Supplementary Materials for Ancient DNA reveals a multistep spread of the first herders into sub-Saharan Africa". Science 365 (6448): eaaw6275. doi:10.1126/science.aaw6275. OCLC 8168339433. PMID 31147405. Bibcode: 2019Sci...365.6275P.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 35.4 Skoglund, Pontus (September 2017). "Reconstructing Prehistoric African Population Structure". Cell 171 (1): 59–71.e21. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.049. ISSN 0092-8674. OCLC 7144495602. PMID 28938123.

|

KSF

KSF