The Geographical Pivot of History

Topic: History

From HandWiki - Reading time: 5 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 5 min

Halford John Mackinder, the author | |

| Author | Halford John Mackinder |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

Publication date | 1904 |

| Media type | Paper |

"The Geographical Pivot of History" is an article submitted by Halford John Mackinder in 1904 to the Royal Geographical Society that advances his heartland theory.[1][2][3] In this article, Mackinder extended the scope of geopolitical analysis to encompass the entire globe.

The World-Island and the Heartland

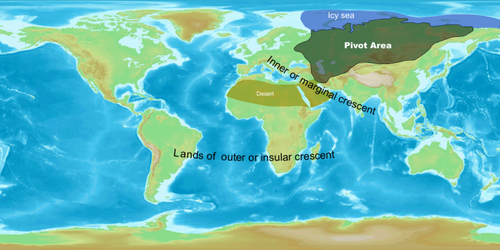

According to Mackinder, the Earth's land surface was divisible into:

- The World-Island, comprising the interlinked continents of Europe, Asia, and Africa (Afro-Eurasia). This was the largest, most populous, and richest of all possible land combinations.

- The offshore islands, including the British Isles and the Japan .

- The outlying islands, including the continents of North America, South America, and Oceania.

The Heartland lay at the centre of the world island, stretching from the Volga to the Yangtze and from the Himalayas to the Arctic. Mackinder's Heartland was the area then ruled by the Russian Empire and after that by the Soviet Union, minus the Kamchatka Peninsula region, which is located in the easternmost part of Russia, near the Aleutian Islands and Kurile islands.

Strategic importance of Eastern Europe

Later, in 1919, Mackinder summarised his theory thus:

Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland;

who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island;

who rules the World-Island commands the world.

Any power which controlled the World-Island would control well over 50% of the world's resources. The Heartland's size and central position made it the key to controlling the World-Island.

The vital question was how to secure control for the Heartland. This question may seem pointless, since in 1904 the Russian Empire had ruled most of the area from the Volga to Eastern Siberia for centuries. But throughout the nineteenth century:

- The West European powers had combined, usually successfully, in the Great Game to prevent Russian expansion.

- The Russian Empire was huge but socially, politically and technologically backward – i.e. inferior in "virility, equipment and organization".

Mackinder held that effective political domination of the Heartland by a single power had been unattainable in the past because:

- The Heartland was protected from sea power by ice to the north and mountains and deserts to the south.

- Previous land invasions from east to west and vice versa were unsuccessful because lack of efficient transportation made it impossible to assure a continual stream of men and supplies.

He outlined the following ways in which the Heartland might become a springboard for global domination in the twentieth century (Sempa, 2000):

- Successful invasion of Russia by a Western European nation (most probably Germany ). Mackinder believed that the introduction of the railroad had removed the Heartland's invulnerability to land invasion. As Eurasia began to be covered by an extensive network of railroads, there was an excellent chance that a powerful continental nation could extend its political control over the Eastern European gateway to the Eurasian landmass. In Mackinder's words, "Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland."

- A Russo-German alliance. Before 1917 both countries were ruled by autocrats (the Tsar and the Kaiser), and both could have been attracted to an alliance against the democratic powers of Western Europe (the US was isolationist regarding European affairs, until it became a participant of World War I in 1917). Germany would have contributed to such an alliance its formidable army and its large and growing sea power.

- Conquest of Russia by a Sino-Japanese empire (see below).

The combined empires' large East Asian coastline would also provide the potential for it to become a major sea power. Mackinder's "Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland" does not cover this scenario, probably because the previous two scenarios were seen as the major risks of the nineteenth century and the early 1900s.

One of Mackinder's personal objectives was to warn Britain that its traditional reliance on sea power would become a weakness as improved land transport opened up the Heartland for invasion and/or industrialisation (Sempa, 2000).

A more modern development to which the heartland theory can still be attributed to exist is through Russia's oil pipelines scandals. Heartland theory implies that the world island is full of resources to be exploited. "Any initiative by the United States to open the market access in Central Asia implies that this state is targeted for the exploration of multinational energy companies. The efforts of domination for the exploration of natural resources are also apparent in the case of Russia. Study found that Russia wants to have pipelines be transported through its territory. However the Russian energy companies are working on behalf of market interests, they often constrain the behaviour of the state".[4]

Influence on other geopolitical models

Signs of Mackinder's Heartland Theory can be found in the works of geopolitician Dimitri Kitsikis, particularly in his "Intermediate Region" model. There is a significant geographical overlap between the Heartland or "Pivot Area" and the Intermediate Region, with the exception of Germany -Prussia and north-eastern China , which Kitsikis excludes from the Intermediate Region. Mackinder, on the other hand, excludes North Africa, Eastern Europe and the Middle East from the Heartland. The reason for this difference is that Mackinder's model is primarily geo-strategic, while Kitsikis' model is geo-civilizational. However, the roles of both the Intermediate Region and the Heartland are regarded by their respective authors as being pivotal in the shaping of world history.

Criticism

K. S. Gadzhev, in his book Introduction to Geopolitics (Введение в геополитику, Vvedenie v geopolitiku), raises a series of objections to Mackinder's Heartland; to start with that the significance physiography is given there for political strategy is a form of geographical determinism.[5]

Critics of the theory also argue that in modern day practice, the theory is outdated due to the evolution of technological warfare, as at the time of publication, Mackinder only considered land and sea powers. In modern day time there are possibilities of attacking a rival without the need for a direct invasion via cyber attacks, aircraft or even use of long range missile strikes.

Other critics of the theory argue that "Mackinderian analysis is not rational because it assumes conflict in a system where there is none".[4]

Mackinder's theory was also never fully proven[6] as no singular power in history has had control of all three of the regions at the same time. The closest this ever occurred was during the Crimean War (1853–1856) whereby Russia attempted to fight for control over the Crimean Peninsula, ultimately losing to the French and the British.

See also

- Intermediate Region

- The Grand Chessboard

- Land hemisphere

- Rimland

- Mainland invasion of the United States

References

- ↑ Mackinder, H. J., "The Geographical Pivot of History", The Geographical Journal, Vol. 23, No.4, (April 1904), pp. 421–437

- ↑ Mackinder, H. J., Democratic Ideals and Reality. A Study in the Politics of Reconstruction, National Defense University Press, 1996, pp. 175–193

- ↑ Charles Kruszewski, "The Pivot of History", Foreign Affairs, April 1954

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Chowdhury, Suban Kumar; Hel Kafi, Abdullah (2015). "The Heartland theory of Sir Halford John Mackinder: justification of foreign policy of the United States and Russia in Central Asia" (in en). Journal of Liberty and International Affairs 1 (2): 58–70. ISSN 1857-9760. https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/44627.

- ↑ Anita Sengupta, Heartlands of Eurasia: The Geopolitics of Political Space, Lexington Books, 2009

- ↑ Rosenberg, Matt (19 January 2022). "What Is Mackinder's Heartland Theory?". https://www.thoughtco.com/what-is-mackinders-heartland-theory-4068393.

Further reading

- CIA's Analysis of the Soviet Union, 1947–1991 links to a large number of CIA analyses of Soviet economic, technological and military capability (as well as e.g. foreign policy), all in PDF format.

- Christopher, J.F. "Sir Halford Mackinder, Geopolitics, and Policymaking in the 21st Century", Parameters, Summer 2000

- Mackinder, H.J. "The Geographical Pivot of History", in "Democratic Ideals and Reality", Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 1996, pp. 175–193.

- Odom, W.E. (1998) "The Collapse of the Soviet Military". Yale University Press. ISBN:0-300-08271-1

- Sempa, F.P. (2000) "Mackinder's World" describes the background to Mackinder's thinking, the development of his theory after World War I (with many quotes) and its influence on geo-strategic thinking.

- Venier, Pascal. "The Geographical Pivot of History and Early 20th Century Geopolitical Culture", Geographical Journal, vol. 170, no 4, December 2004, pp. 330–336.

- William R. Keylor, The Twentieth-Century World and Beyond: An International History Since 1900, 2006. ISBN:0-19-516843-7

External links

- The Geographical Pivot of History (The Internet Archive version) The Geographical Journal, April 1904.

- Democratic Ideals and Reality, Washington, DC: National Defence University Press, 1996, pp. 175–194

KSF

KSF