Integer

From HandWiki - Reading time: 18 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 18 min

| Algebraic structure → Group theory Group theory |

|---|

|

An integer is the number zero (0), a positive natural number (1, 2, 3, etc.) or a negative integer (−1, −2, −3, etc.).[1] The negative numbers are the additive inverses of the corresponding positive numbers.[2] The set of all integers is often denoted by the boldface Z or blackboard bold .[3][4]

The set of natural numbers is a subset of , which in turn is a subset of the set of all rational numbers , itself a subset of the real numbers .[lower-alpha 1] Like the set of natural numbers, the set of integers is countably infinite. An integer may be regarded as a real number that can be written without a fractional component. For example, 21, 4, 0, and −2048 are integers, while 9.75, 5+1/2, and √2 are not.[8]

The integers form the smallest group and the smallest ring containing the natural numbers. In algebraic number theory, the integers are sometimes qualified as rational integers to distinguish them from the more general algebraic integers. In fact, (rational) integers are algebraic integers that are also rational numbers.

History

The word integer comes from the Latin integer meaning "whole" or (literally) "untouched", from in ("not") plus tangere ("to touch"). "Entire" derives from the same origin via the French word entier, which means both entire and integer.[9] Historically the term was used for a number that was a multiple of 1,[10][11] or to the whole part of a mixed number.[12][13] Only positive integers were considered, making the term synonymous with the natural numbers. The definition of integer expanded over time to include negative numbers as their usefulness was recognized.[14] For example Leonhard Euler in his 1765 Elements of Algebra defined integers to include both positive and negative numbers.[15] However, European mathematicians, for the most part, resisted the concept of negative numbers until the middle of the 19th century.[14]

The use of the letter Z to denote the set of integers comes from the German word Zahlen ("numbers")[3][4] and has been attributed to David Hilbert.[16] The earliest known use of the notation in a textbook occurs in Algébre written by the collective Nicolas Bourbaki, dating to 1947.[3][17] The notation was not adopted immediately, for example another textbook used the letter J[18] and a 1960 paper used Z to denote the non-negative integers.[19] But by 1961, Z was generally used by modern algebra texts to denote the positive and negative integers.[20]

The symbol is often annotated to denote various sets, with varying usage amongst different authors: , or for the positive integers, or for non-negative integers, and for non-zero integers. Some authors use for non-zero integers, while others use it for non-negative integers, or for {–1, 1} (the group of units of ). Additionally, is used to denote either the set of integers modulo p (i.e., the set of congruence classes of integers), or the set of p-adic integers.[21][22]

The whole numbers were synonymous with the integers up until the early 1950s.[23][24][25] In the late 1950s, as part of the New Math movement,[26] American elementary school teachers began teaching that "whole numbers" referred to the natural numbers, excluding negative numbers, while "integer" included the negative numbers.[27][28] "Whole number" remains ambiguous to the present day.[29]

Algebraic properties

| Algebraic structure → Ring theory Ring theory |

|---|

|

Like the natural numbers, is closed under the operations of addition and multiplication, that is, the sum and product of any two integers is an integer. However, with the inclusion of the negative natural numbers (and importantly, 0), , unlike the natural numbers, is also closed under subtraction.[30]

The integers form a unital ring which is the most basic one, in the following sense: for any unital ring, there is a unique ring homomorphism from the integers into this ring. This universal property, namely to be an initial object in the category of rings, characterizes the ring .

is not closed under division, since the quotient of two integers (e.g., 1 divided by 2) need not be an integer. Although the natural numbers are closed under exponentiation, the integers are not (since the result can be a fraction when the exponent is negative).

The following table lists some of the basic properties of addition and multiplication for any integers a, b and c:

| Addition | Multiplication | |

|---|---|---|

| Closure: | a + b is an integer | a × b is an integer |

| Associativity: | a + (b + c) = (a + b) + c | a × (b × c) = (a × b) × c |

| Commutativity: | a + b = b + a | a × b = b × a |

| Existence of an identity element: | a + 0 = a | a × 1 = a |

| Existence of inverse elements: | a + (−a) = 0 | The only invertible integers (called units) are −1 and 1. |

| Distributivity: | a × (b + c) = (a × b) + (a × c) and (a + b) × c = (a × c) + (b × c) | |

| No zero divisors: | If a × b = 0, then a = 0 or b = 0 (or both) | |

The first five properties listed above for addition say that , under addition, is an abelian group. It is also a cyclic group, since every non-zero integer can be written as a finite sum 1 + 1 + ... + 1 or (−1) + (−1) + ... + (−1). In fact, under addition is the only infinite cyclic group—in the sense that any infinite cyclic group is isomorphic to .

The first four properties listed above for multiplication say that under multiplication is a commutative monoid. However, not every integer has a multiplicative inverse (as is the case of the number 2), which means that under multiplication is not a group.

All the rules from the above property table (except for the last), when taken together, say that together with addition and multiplication is a commutative ring with unity. It is the prototype of all objects of such algebraic structure. Only those equalities of expressions are true in for all values of variables, which are true in any unital commutative ring. Certain non-zero integers map to zero in certain rings.

The lack of zero divisors in the integers (last property in the table) means that the commutative ring is an integral domain.

The lack of multiplicative inverses, which is equivalent to the fact that is not closed under division, means that is not a field. The smallest field containing the integers as a subring is the field of rational numbers. The process of constructing the rationals from the integers can be mimicked to form the field of fractions of any integral domain. And back, starting from an algebraic number field (an extension of rational numbers), its ring of integers can be extracted, which includes as its subring.

Although ordinary division is not defined on , the division "with remainder" is defined on them. It is called Euclidean division, and possesses the following important property: given two integers a and b with b ≠ 0, there exist unique integers q and r such that a = q × b + r and 0 ≤ r < |b|, where |b| denotes the absolute value of b. The integer q is called the quotient and r is called the remainder of the division of a by b. The Euclidean algorithm for computing greatest common divisors works by a sequence of Euclidean divisions.

The above says that is a Euclidean domain. This implies that is a principal ideal domain, and any positive integer can be written as the products of primes in an essentially unique way.[31] This is the fundamental theorem of arithmetic.

Order-theoretic properties

is a totally ordered set without upper or lower bound. The ordering of is given by: :... −3 < −2 < −1 < 0 < 1 < 2 < 3 < ... An integer is positive if it is greater than zero, and negative if it is less than zero. Zero is defined as neither negative nor positive.

The ordering of integers is compatible with the algebraic operations in the following way:

- if a < b and c < d, then a + c < b + d

- if a < b and 0 < c, then ac < bc.

Thus it follows that together with the above ordering is an ordered ring.

The integers are the only nontrivial totally ordered abelian group whose positive elements are well-ordered.[32] This is equivalent to the statement that any Noetherian valuation ring is either a field—or a discrete valuation ring.

Construction

Traditional development

In elementary school teaching, integers are often intuitively defined as the union of the (positive) natural numbers, zero, and the negations of the natural numbers. This can be formalized as follows.[33] First construct the set of natural numbers according to the Peano axioms, call this . Then construct a set which is disjoint from and in one-to-one correspondence with via a function . For example, take to be the ordered pairs with the mapping . Finally let 0 be some object not in or , for example the ordered pair . Then the integers are defined to be the union .

The traditional arithmetic operations can then be defined on the integers in a piecewise fashion, for each of positive numbers, negative numbers, and zero. For example negation is defined as follows:

The traditional style of definition leads to many different cases (each arithmetic operation needs to be defined on each combination of types of integer) and makes it tedious to prove that integers obey the various laws of arithmetic.[34]

Equivalence classes of ordered pairs

In modern set-theoretic mathematics, a more abstract construction[35][36] allowing one to define arithmetical operations without any case distinction is often used instead.[37] The integers can thus be formally constructed as the equivalence classes of ordered pairs of natural numbers (a,b).[38]

The intuition is that (a,b) stands for the result of subtracting b from a.[38] To confirm our expectation that 1 − 2 and 4 − 5 denote the same number, we define an equivalence relation ~ on these pairs with the following rule:

precisely when

Addition and multiplication of integers can be defined in terms of the equivalent operations on the natural numbers;[38] by using [(a,b)] to denote the equivalence class having (a,b) as a member, one has:

The negation (or additive inverse) of an integer is obtained by reversing the order of the pair:

Hence subtraction can be defined as the addition of the additive inverse:

The standard ordering on the integers is given by:

It is easily verified that these definitions are independent of the choice of representatives of the equivalence classes.

Every equivalence class has a unique member that is of the form (n,0) or (0,n) (or both at once). The natural number n is identified with the class [(n,0)] (i.e., the natural numbers are embedded into the integers by map sending n to [(n,0)]), and the class [(0,n)] is denoted −n (this covers all remaining classes, and gives the class [(0,0)] a second time since −0 = 0.

Thus, [(a,b)] is denoted by

If the natural numbers are identified with the corresponding integers (using the embedding mentioned above), this convention creates no ambiguity.

This notation recovers the familiar representation of the integers as {..., −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, ...} .

Some examples are:

Other approaches

In theoretical computer science, other approaches for the construction of integers are used by automated theorem provers and term rewrite engines. Integers are represented as algebraic terms built using a few basic operations (e.g., zero, succ, pred) and, possibly, using natural numbers, which are assumed to be already constructed (using, say, the Peano approach).

There exist at least ten such constructions of signed integers.[39] These constructions differ in several ways: the number of basic operations used for the construction, the number (usually, between 0 and 2) and the types of arguments accepted by these operations; the presence or absence of natural numbers as arguments of some of these operations, and the fact that these operations are free constructors or not, i.e., that the same integer can be represented using only one or many algebraic terms.

The technique for the construction of integers presented in the previous section corresponds to the particular case where there is a single basic operation pair that takes as arguments two natural numbers and , and returns an integer (equal to ). This operation is not free since the integer 0 can be written pair(0,0), or pair(1,1), or pair(2,2), etc. This technique of construction is used by the proof assistant Isabelle; however, many other tools use alternative construction techniques, notable those based upon free constructors, which are simpler and can be implemented more efficiently in computers.

Computer science

An integer is often a primitive data type in computer languages. However, integer data types can only represent a subset of all integers, since practical computers are of finite capacity. Also, in the common two's complement representation, the inherent definition of sign distinguishes between "negative" and "non-negative" rather than "negative, positive, and 0". (It is, however, certainly possible for a computer to determine whether an integer value is truly positive.) Fixed length integer approximation data types (or subsets) are denoted int or Integer in several programming languages (such as Algol68, C, Java, Delphi, etc.).

Variable-length representations of integers, such as bignums, can store any integer that fits in the computer's memory. Other integer data types are implemented with a fixed size, usually a number of bits which is a power of 2 (4, 8, 16, etc.) or a memorable number of decimal digits (e.g., 9 or 10).

Cardinality

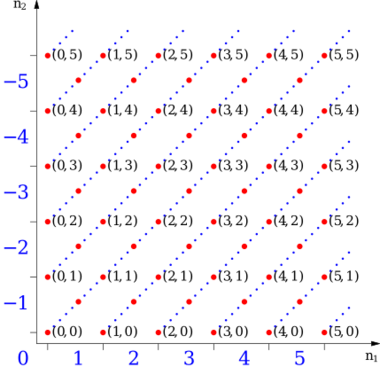

The set of integers is countably infinite, meaning it is possible to pair each integer with a unique natural number. An example of such a pairing is

- (0, 1), (1, 2), (−1, 3), (2, 4), (−2, 5), (3, 6), . . . , (1 − k, 2k − 1), (k, 2k ), . . .

More technically, the cardinality of is said to equal ℵ0 (aleph-null). The pairing between elements of and is called a bijection.

See also

- Canonical factorization of a positive integer

- Hyperinteger

- Integer complexity

- Integer lattice

- Integer part

- Integer sequence

- Integer-valued function

- Mathematical symbols

- Parity (mathematics)

- Profinite integer

Footnotes

- ↑ More precisely, each system is embedded in the next, isomorphically mapped to a subset.[5] The commonly-assumed set-theoretic containment may be obtained by constructing the reals, discarding any earlier constructions, and defining the other sets as subsets of the reals.[6] Such a convention is "a matter of choice", yet not.[7]

References

- ↑ (in en) Science and Technology Encyclopedia. University of Chicago Press. September 2000. p. 280. ISBN 978-0-226-74267-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=PZIdcYCCf2kC&dq=integer&pg=PA280.

- ↑ "Integers: Introduction to the concept, with activities comparing temperatures and money. | Unit 1" (in en). https://www.oercommons.org/authoring/13198-integers-introduction-to-the-concept-with-activiti/1/view.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Miller, Jeff (2010-08-29). "Earliest Uses of Symbols of Number Theory". http://jeff560.tripod.com/nth.html.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Peter Jephson Cameron (1998). Introduction to Algebra. Oxford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-19-850195-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=syYYl-NVM5IC&pg=PA4. Retrieved 2016-02-15.

- ↑ Partee, Barbara H.; Meulen, Alice ter; Wall, Robert E. (30 April 1990) (in en). Mathematical Methods in Linguistics. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 78–82. ISBN 978-90-277-2245-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=qV7TUuaYcUIC&pg=PA80. "The natural numbers are not themselves a subset of this set-theoretic representation of the integers. Rather, the set of all integers contains a subset consisting of the positive integers and zero which is isomorphic to the set of natural numbers."

- ↑ Wohlgemuth, Andrew (10 June 2014) (in en). Introduction to Proof in Abstract Mathematics. Courier Corporation. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-486-14168-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=PEP_AwAAQBAJ&pg=PA237.

- ↑ Polkinghorne, John (19 May 2011) (in en). Meaning in Mathematics. OUP Oxford. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-19-162189-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=DCqQDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA68.

- ↑ Prep, Kaplan Test (4 June 2019) (in en). GMAT Complete 2020: The Ultimate in Comprehensive Self-Study for GMAT. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-5062-4844-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=6l_sDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA708.

- ↑ Evans, Nick (1995). "A-Quantifiers and Scope". in Bach, Emmon W.. Quantification in Natural Languages. Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 262. ISBN 978-0-7923-3352-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=NlQL97qBSZkC.

- ↑ Smedley, Edward; Rose, Hugh James; Rose, Henry John (1845) (in en). Encyclopædia Metropolitana. B. Fellowes. p. 537. https://books.google.com/books?id=ZVI_AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA537. "An integer is a multiple of unity"

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Britannica 1771, p. 367

- ↑ Pisano, Leonardo; Boncompagni, Baldassarre (transliteration) (1202). Incipit liber Abbaci compositus to Lionardo filio Bonaccii Pisano in year Mccij (Manuscript). Museo Galileo. p. 30. https://bibdig.museogalileo.it/tecanew/opera?bid=1072400&seq=30. "Nam rupti uel fracti semper ponendi sunt post integra, quamuis prius integra quam rupti pronuntiari debeant."

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Britannica 1771, p. 83

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Martinez, Alberto (2014). Negative Math. Princeton University Press. pp. 80–109.

- ↑ Euler, Leonhard (1771). Vollstandige Anleitung Zur Algebra. 1. p. 10. https://archive.org/details/1770LEULERVollstandigeAnleitungZurAlgebraVol1/page/n31/mode/2up. "Alle diese Zahlen, so wohl positive als negative, führen den bekannten Nahmen der gantzen Zahlen, welche also entweder größer oder kleiner sind als nichts. Man nennt dieselbe gantze Zahlen, um sie von den gebrochenen, und noch vielerley andern Zahlen, wovon unten gehandelt werden wird, zu unterscheiden."

- ↑ (in en) The University of Leeds Review. 31-32. University of Leeds.. 1989. p. 46. https://books.google.com/books?id=Z-7kAAAAMAAJ. "Incidentally, Z comes from "Zahl": the notation was created by Hilbert."

- ↑ Bourbaki, Nicolas (1951) (in fr). Algèbre, Chapter 1 (2nd ed.). Paris: Hermann. p. 27. https://archive.org/details/algebrebour00bour/page/26/mode/2up. "Le symétrisé de N se note Z; ses éléments sont appelés entiers rationnels."

- ↑ Birkhoff, Garrett (1948). Lattice Theory (Revised ed.). American Mathematical Society. p. 63. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.166886/page/n63/mode/2up. "the set J of all integers"

- ↑ Society, Canadian Mathematical (1960) (in en). Canadian Journal of Mathematics. Canadian Mathematical Society. p. 374. https://books.google.com/books?id=uMAXOmLTCGsC&dq=integer%20set%20Z&pg=PA374. "Consider the set Z of non-negative integers"

- ↑ Bezuszka, Stanley (1961) (in en). Contemporary Progress in Mathematics: Teacher Supplement [to Part 1 and Part 2]. Boston College. p. 69. https://books.google.com/books?id=dhJPAQAAMAAJ&q=integer+set+Z. "Modern Algebra texts generally designate the set of integers by the capital letter Z."

- ↑ Keith Pledger and Dave Wilkins, "Edexcel AS and A Level Modular Mathematics: Core Mathematics 1" Pearson 2008

- ↑ LK Turner, FJ BUdden, D Knighton, "Advanced Mathematics", Book 2, Longman 1975.

- ↑ Mathews, George Ballard (1892) (in en). Theory of Numbers. Deighton, Bell and Company. p. 2. https://books.google.com/books?id=iQ_vAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA2.

- ↑ Betz, William (1934) (in en). Junior Mathematics for Today. Ginn. https://books.google.com/books?id=RzNCAAAAIAAJ. "The whole numbers, or integers, when arranged in their natural order, such as 1, 2, 3, are called consecutive integers."

- ↑ Peck, Lyman C. (1950) (in en). Elements of Algebra. McGraw-Hill. p. 3. https://books.google.com/books?id=tclXAAAAYAAJ&q=integers+whole+numbers. "The numbers which so arise are called positive whole numbers, or positive integers."

- ↑ Hayden, Robert (1981). A history of the "new math" movement in the United States (PhD). Iowa State University. p. 145. doi:10.31274/rtd-180813-5631.

A much more influential force in bringing news of the "new math" to high school teachers and administrators was the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM).

- ↑ (in en) The Growth of Mathematical Ideas, Grades K-12: 24th Yearbook. National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. 1959. p. 14. ISBN 9780608166186. https://books.google.com/books?id=OO9RAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA14.

- ↑ Deans, Edwina (1963) (in en). Elementary School Mathematics: New Directions. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Office of Education. p. 42. https://books.google.com/books?id=bAUJAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA42.

- ↑ "entry: whole number". HarperCollins. https://www.ahdictionary.com/word/search.html?q=whole+number.

- ↑ "Integer | mathematics" (in en). https://www.britannica.com/science/integer.

- ↑ Lang, Serge (1993). Algebra (3rd ed.). Addison-Wesley. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0-201-55540-0.

- ↑ Warner, Seth (2012). Modern Algebra. Dover Books on Mathematics. Courier Corporation. Theorem 20.14, p. 185. ISBN 978-0-486-13709-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=TqHDAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA185. Retrieved 2015-04-29..

- ↑ Mendelson, Elliott (1985). Number systems and the foundations of analysis. Malabar, Fla. : R.E. Krieger Pub. Co.. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-89874-818-5. https://archive.org/details/numbersystemsfou0000mend/page/152/mode/2up.

- ↑ Mendelson, Elliott (2008). Number Systems and the Foundations of Analysis. Dover Books on Mathematics. Courier Dover Publications. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-486-45792-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=3domViIV7HMC&pg=PA86. Retrieved 2016-02-15..

- ↑ Ivorra Castillo: Álgebra

- ↑ Kramer, Jürg; von Pippich, Anna-Maria (2017) (in en). From Natural Numbers to Quaternions (1st ed.). Switzerland: Springer Cham. pp. 78–81. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-69429-0. ISBN 978-3-319-69427-6.

- ↑ Frobisher, Len (1999). Learning to Teach Number: A Handbook for Students and Teachers in the Primary School. The Stanley Thornes Teaching Primary Maths Series. Nelson Thornes. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-7487-3515-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=KwJQIt4jQHUC&pg=PA126. Retrieved 2016-02-15..

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Campbell, Howard E. (1970). The structure of arithmetic. Appleton-Century-Crofts. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-390-16895-5. https://archive.org/details/structureofarith00camp/page/83.

- ↑ Garavel, Hubert (2017). "On the Most Suitable Axiomatization of Signed Integers". Post-proceedings of the 23rd International Workshop on Algebraic Development Techniques (WADT'2016). 10644. Springer. pp. 120–134. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-72044-9_9. ISBN 978-3-319-72043-2. https://hal.inria.fr/hal-01667321. Retrieved 2018-01-25.

Sources

- Bell, E.T. (1986). Men of Mathematics. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-46400-0.)

- Herstein, I.N. (1975). Topics in Algebra (2nd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0-471-01090-1.

- Mac Lane, Saunders; Birkhoff, Garrett (1999). Algebra (3rd ed.). American Mathematical Society. ISBN 0-8218-1646-2.

- A Society of Gentlemen in Scotland (1771) (in en). Encyclopaedia Britannica. Edinburgh. https://books.google.com/books?id=d50qAQAAMAAJ.

External links

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Integer", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=p/i051290

- The Positive Integers – divisor tables and numeral representation tools

- On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences cf OEIS

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "Integer". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Integer.html.

|

KSF

KSF