Lax–Friedrichs method

From HandWiki - Reading time: 4 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 4 min

The Lax–Friedrichs method, named after Peter Lax and Kurt O. Friedrichs, is a numerical method for the solution of hyperbolic partial differential equations based on finite differences. The method can be described as the FTCS (forward in time, centered in space) scheme with a numerical dissipation term of 1/2. One can view the Lax–Friedrichs method as an alternative to Godunov's scheme, where one avoids solving a Riemann problem at each cell interface, at the expense of adding artificial viscosity.

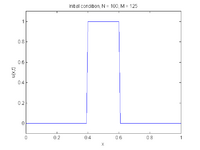

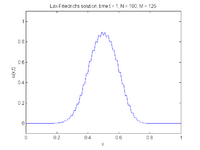

Illustration for a Linear Problem

Consider a one-dimensional, linear hyperbolic partial differential equation for [math]\displaystyle{ u(x,t) }[/math] of the form: [math]\displaystyle{ u_t + a u_x = 0 }[/math] on the domain [math]\displaystyle{ b \leq x \leq c,\; 0 \leq t \leq d }[/math] with initial condition [math]\displaystyle{ u(x,0) = u_0(x)\, }[/math] and the boundary conditions [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} u(b,t) &= u_b(t) \\ u(c,t) &= u_c(t). \end{align} }[/math]

If one discretizes the domain [math]\displaystyle{ (b, c) \times (0, d) }[/math] to a grid with equally spaced points with a spacing of [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta x }[/math] in the [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math]-direction and [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta t }[/math] in the [math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math]-direction, we introduce an approximation [math]\displaystyle{ \tilde u }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ u_i^n = \tilde u(x_i, t^n) ~~\text{ with }~~ \begin{array}{l}x_i = b + i\,\Delta x ,\\ t^n = n\,\Delta t\end{array} ~~\text{ for }~~ \begin{array}{l}i = 0,\ldots,N ,\\ n = 0,\ldots,M,\end{array} }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ N = \frac{c - b}{\Delta x} ,\, M = \frac{d}{\Delta t} }[/math] are integers representing the number of grid intervals. Then the Lax–Friedrichs method to approximate the partial differential equation is given by: [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{u_i^{n+1} - \frac{1}{2}(u_{i+1}^n + u_{i-1}^n)}{\Delta t} + a\frac{u_{i+1}^n - u_{i-1}^n}{2\,\Delta x} = 0 }[/math]

Or, rewriting this to solve for the unknown [math]\displaystyle{ u_i^{n+1}, }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ u_i^{n+1} = \frac{1}{2} \left(u_{i+1}^n + u_{i-1}^n\right) - a\frac{\Delta t}{2\,\Delta x} \left(u_{i+1}^n - u_{i-1}^n\right) }[/math]

Where the initial values and boundary nodes are taken from [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} u_i^0 &= u_0(x_i) \\ u_0^n &= u_b(t^n) \\ u_N^n &= u_c(t^n). \end{align} }[/math]

Extensions to Nonlinear Problems

A nonlinear hyperbolic conservation law is defined through a flux function [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math]: [math]\displaystyle{ u_t + ( f(u) )_x = 0. }[/math]

In the case of [math]\displaystyle{ f(u) = a u }[/math], we end up with a scalar linear problem. Note that in general, [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] is a vector with [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] equations in it. The generalization of the Lax-Friedrichs method to nonlinear systems takes the form[1] [math]\displaystyle{ u_i^{n+1} = \frac{1}{2} \left(u_{i+1}^n + u_{i-1}^n\right) - \frac{\Delta t}{2\,\Delta x} \left( f( u_{i+1}^n ) - f( u_{i-1}^n ) \right). }[/math]

This method is conservative and first order accurate, hence quite dissipative. It can, however be used as a building block for building high-order numerical schemes for solving hyperbolic partial differential equations, much like Euler time steps can be used as a building block for creating high-order numerical integrators for ordinary differential equations.

We note that this method can be written in conservation form: [math]\displaystyle{ u_i^{n+1} = u^n_i - \frac{\Delta t}{ \Delta x} \left( \hat{f}^n_{i+1/2} - \hat{f}^n_{i-1/2} \right), }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{f}^n_{i-1/2} = \frac{1}{2} \left( f_{i-1} + f_{i} \right) - \frac{ \Delta x}{ 2 \Delta t } \left( u^n_{i} - u^n_{i-1} \right). }[/math]

Without the extra terms [math]\displaystyle{ u^n_i }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ u^n_{i-1} }[/math] in the discrete flux, [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{f}^n_{i-1/2} }[/math], one ends up with the FTCS scheme, which is well known to be unconditionally unstable for hyperbolic problems.

Stability and accuracy

This method is explicit and first order accurate in time and first order accurate in space ([math]\displaystyle{ O(\Delta t) + O({\Delta x^2}/{\Delta t})) }[/math] provided [math]\displaystyle{ u_0(x),\, u_b(t),\, u_c(t) }[/math] are sufficiently-smooth functions. Under these conditions, the method is stable if and only if the following condition is satisfied: [math]\displaystyle{ \left| a\frac{\Delta t}{\Delta x} \right| \leq 1. }[/math]

(A von Neumann stability analysis can show the necessity of this stability condition.) The Lax–Friedrichs method is classified as having second-order dissipation and third order dispersion.[2] For functions that have discontinuities, the scheme displays strong dissipation and dispersion;[3] see figures at right.

References

- ↑ LeVeque, Randall J. (1992). Numerical methods for conservation laws. Basel: Birkhäuser Verlag. p. 125. ISBN 978-3-0348-8629-1. OCLC 828775522. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/828775522.

- ↑ Chu, C. K. (1978), Numerical Methods in Fluid Mechanics, Advances in Applied Mechanics, 18, New York: Academic Press, p. 304, ISBN 978-0-12-002018-8

- ↑ Thomas, J. W. (1995), Numerical Partial Differential Equations: Finite Difference Methods, Texts in Applied Mathematics, 22, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, §7.8, ISBN 978-0-387-97999-1

- DuChateau, Paul; Zachmann, David (2002), Applied Partial Differential Equations, New York: Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0-486-41976-3, https://archive.org/details/appliedpartialdi00duch

- Press, William H; Teukolsky, SA; Vetterling, WT; Flannery, BP (2007), "Section 20.1.2. Lax Method", Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing (3rd ed.), New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-88068-8, http://apps.nrbook.com/empanel/index.html#pg=1034

|

KSF

KSF