Alcohols

Topic: Medicine

From HandWiki - Reading time: 8 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 8 min

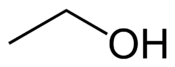

Ethanol is a commonly used medical alcohol. | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | Topical, intravenous, by mouth |

| Drug class | Antiseptics, disinfectants, antidotes |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

Alcohols, in various forms, are used within medicine as an antiseptic, disinfectant, and antidote.[1] Alcohols applied to the skin are used to disinfect skin before a needle stick and before surgery.[2] They may be used both to disinfect the skin of the person and as hand sanitizer of the healthcare providers.[2] They can also be used to clean other areas[2] and in mouthwashes.[3][4][5] Taken by mouth or injected into a vein, ethanol is used to treat methanol or ethylene glycol toxicity when fomepizole is not available.[1]

Side effects of alcohols applied to the skin include skin irritation.[2] Care should be taken with electrocautery, as ethanol is flammable.[1] Types of alcohol used include ethanol, denatured ethanol, 1-propanol, and isopropyl alcohol.[6][7] Alcohols are effective against a range of microorganisms, though they do not inactivate spores.[7] Concentrations of 60 to 90% work best.[7]

Alcohol has been used as an antiseptic as early as 1363, with evidence to support its use becoming available in the late 1800s.[8] Commercial formulations of hand sanitizer or with other agents such as chlorhexidine are available.[7][9]

Medical uses

95% ABV ethanol is known as spiritus fortis in medical context.

Antiseptics and disinfectants

Ethanol is listed under Antiseptics, and Alcohol based hand rub under Disinfectants, on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[10]

Applied to the skin, alcohols are used to disinfect skin before a needle stick and before surgery.[2] They may be used both to disinfect the skin of the person and the hands of the healthcare providers.[2] They can also be used to clean other areas,[2] and in mouthwashes.[3]

Both ethanol and isopropyl alcohol are common ingredients in topical antiseptics, including hand sanitizer.[11]

Treatment for ethylene glycol toxicity, and methanol toxicity

When taken by mouth or injected into a vein ethanol is used to treat methanol or ethylene glycol toxicity[12] when fomepizole is not available.[1]

Mechanism

Ethanol, when used for toxicity, competes with other alcohols for the alcohol dehydrogenase enzyme, lessening metabolism into toxic aldehyde and carboxylic acid derivatives, and reducing more serious toxic effect of the glycols to crystallize in the kidneys.[13]

Sclerosant

Absolute ethanol is used as a sclerosant in sclerotherapy. Sclerotherapy has been used "in the treatment of simple pleural effusions, vascular malformations, lymphocytes and seromas."[14]

Sedative

Ethchlorvynol, developed in the 1950s, was used to treat insomnia, but prescriptions for the drug had fallen significantly by 1990, as other hypnotics that were considered safer (i.e., less dangerous in overdose) became much more common. It is no longer prescribed in the United States due to unavailability, but it is still available in some countries and would still be considered legal to possess and use with a valid prescription.

History

Alcohol has been used as an antiseptic as early as 1363 with evidence to support its use becoming available in the late 1800s.[8] Since antiquity, prior to the development of modern agents, alcohol was used as a general anesthetic.[15]

Methylpentynol, discovered 1913, prescribed for the treatment of insomnia, but its use was quickly phased out in response to newer drugs with far more favorable safety profiles.[16][17][18] The drug has been replaced by benzodiazepines and is no longer sold anywhere.[19]

Society and culture

Economics

Ablysinol (a brand of 99% ethanol medical alcohol) was sold from $1,300 to $10K per 10-pack in 2020 due to FDA administrator action granting exclusivity when used for treating hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy in the US through 2025, despite "misuse" of the orphan drug act.[20][21][22][unreliable source?]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 British National Formulary: BNF 69 (69th ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. pp. 42, 838. ISBN 9780857111562.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. 2009. p. 321. ISBN 9789241547659.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Comprehensive Preventive Dentistry. John Wiley & Sons. 11 April 2012. pp. 138–. ISBN 978-1-118-28020-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=bar1W50pfgEC&pg=PA138.

- ↑ Contemporary Oral Oncology: Biology, Epidemiology, Etiology, and Prevention. Springer. 8 December 2016. pp. 47–54. ISBN 978-3-319-14911-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=qp-wDQAAQBAJ&pg=PA47.

- ↑ "Is synthetic mouthwash the final choice to treat oral malodour?". Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons--Pakistan 24 (10): 757–762. October 2014. PMID 25327922.

- ↑ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)". World Health Organization. April 2015. https://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/EML_2015_FINAL_amended_NOV2015.pdf?ua=1.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 "Antiseptics and disinfectants: activity, action, and resistance". Clinical Microbiology Reviews 12 (1): 147–179. January 1999. doi:10.1128/cmr.12.1.147. PMID 9880479.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 (in en) Disinfection, Sterilization, and Preservation. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2001. p. 14. ISBN 9780683307405. https://books.google.com/books?id=3f-kPJ17_TYC&pg=PA14.

- ↑ "Hand Hygiene: An Update". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America 30 (3): 591–607. September 2016. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2016.04.007. PMID 27515139.

- ↑ World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2019. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ Research, Center for Drug Evaluation and (2023-05-12). "Q&A for Consumers | Hand Sanitizers and COVID-19" (in en). FDA. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/information-drug-class/qa-consumers-hand-sanitizers-and-covid-19.

- ↑ Mégarbane, Bruno (2010-08-24). "Treatment of patients with ethylene glycol or methanol poisoning: focus on fomepizole". Open Access Emergency Medicine 2: 67–75. doi:10.2147/OAEM.S5346. ISSN 1179-1500. PMID 27147840.

- ↑ "American Academy of Clinical Toxicology practice guidelines on the treatment of methanol poisoning". Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology 40 (4): 415–446. 2002. doi:10.1081/CLT-120006745. PMID 12216995.

- ↑ "Sclerotherapy as an alternative treatment for complex, refractory seromas". Journal of Surgical Case Reports (Oxford University Press) 2021 (8): rjab224. August 2021. doi:10.1093/jscr/rjab224. PMID 34447570.

- ↑ The Wondrous Story of Anesthesia. Springer Science & Business Media. 14 September 2013. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-1-4614-8441-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=H--3BAAAQBAJ&pg=PA4.

- ↑ "Methylparafynol--a new type hypnotic. Preliminary report on its therapeutic efficacy and toxicity". American Practitioner and Digest of Treatment 3 (1): 23–6. January 1952. PMID 14903452.

- ↑ "The anticonvulsant activity and toxicity of methylparafynol (dormison) and some other alcohols". Science 116 (3024): 663–5. December 1952. doi:10.1126/science.116.3024.663. PMID 13028241. Bibcode: 1952Sci...116..663S.

- ↑ "[A new type of hypnotic; unsaturated tertiary carbinols; experimental studies on therapeutic use of 3-methyl-pentin-ol-3 (methylparafynol)]". Arzneimittel-Forschung 4 (3): 198–9. March 1954. PMID 13159700.

- ↑ Hines, Richard Devenport (2002). The Pursuit of Oblivion. pp. 327.

- ↑ Paavola, Alia (12 February 2020). "Why price of dehydrated alcohol is going from $1,300 to $10K". www.beckershospitalreview.com. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/pharmacy/why-price-of-dehydrated-alcohol-is-going-from-1-300-to-10k.html.

- ↑ "Biotech executives, having pledged fair pricing, criticize drugmaker for steep hike". BioPharma Dive. https://www.biopharmadive.com/news/belcher-price-increase-biopharma-executive-criticism-letter/572547/.

- ↑ "Statement on Belcher Pharmaceuticals". https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:6635900853532311553/.

KSF

KSF