Cancer immunology

Topic: Medicine

From HandWiki - Reading time: 10 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 10 min

Cancer immunology (immuno-oncology) is an interdisciplinary branch of biology and a sub-discipline of immunology that is concerned with understanding the role of the immune system in the progression and development of cancer; the most well known application is cancer immunotherapy, which utilises the immune system as a treatment for cancer. Cancer immunosurveillance and immunoediting are based on protection against development of tumors in animal systems and (ii) identification of targets for immune recognition of human cancer.

Definition

Cancer immunology is an interdisciplinary branch of biology concerned with the role of the immune system in the progression and development of cancer; the most well known application is cancer immunotherapy, where the immune system is used to treat cancer.[1][2] Cancer immunosurveillance is a theory formulated in 1957 by Burnet and Thomas, who proposed that lymphocytes act as sentinels in recognizing and eliminating continuously arising, nascent transformed cells.[3][4] Cancer immunosurveillance appears to be an important host protection process that decreases cancer rates through inhibition of carcinogenesis and maintaining of regular cellular homeostasis.[5] It has also been suggested that immunosurveillance primarily functions as a component of a more general process of cancer immunoediting.[3]

Tumor antigens

Tumors may express tumor antigens that are recognized by the immune system and may induce an immune response.[6] These tumor antigens are either TSA (Tumor-specific antigen) or TAA (Tumor-associated antigen).[7]

Tumor-specific

Tumor-specific antigens (TSA) are antigens that only occur in tumor cells.[7] TSAs can be products of oncoviruses like E6 and E7 proteins of human papillomavirus, occurring in cervical carcinoma, or EBNA-1 protein of EBV, occurring in Burkitt's lymphoma cells.[8][9] Another example of TSAs are abnormal products of mutated oncogenes (e.g. Ras protein) and anti-oncogenes (e.g. p53).[10]

Tumor-associated antigens

Tumor-associated antigens (TAA) are present in healthy cells, but for some reason they also occur in tumor cells.[7] However, they differ in quantity, place or time period of expression.[11] Oncofetal antigens are tumor-associated antigens expressed by embryonic cells and by tumors.[12] Examples of oncofetal antigens are AFP (α-fetoprotein), produced by hepatocellular carcinoma, or CEA (carcinoembryonic antigen), occurring in ovarian and colon cancer.[13][14] More tumor-associated antigens are HER2/neu, EGFR or MAGE-1.[15][16][17]

Immunoediting

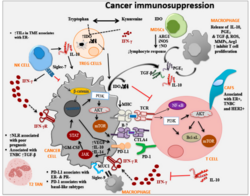

Cancer immunoediting is a process in which immune system interacts with tumor cells. It consists of three phases: elimination, equilibrium and escape. These phases are often referred to as "the three Es" of cancer immunoediting. Both adaptive and innate immune system participate in immunoediting.[18]

In the elimination phase, the immune response leads to destruction of tumor cells and therefore to tumor suppression. However, some tumor cells may gain more mutations, change their characteristics and evade the immune system. These cells might enter the equilibrium phase, in which the immune system does not recognise all tumor cells, but at the same time the tumor does not grow. This condition may lead to the phase of escape, in which the tumor gains dominance over immune system, starts growing and establishes immunosuppressive environment.[19]

As a consequence of immunoediting, tumor cell clones less responsive to the immune system gain dominance in the tumor through time, as the recognized cells are eliminated. This process may be considered akin to Darwinian evolution, where cells containing pro-oncogenic or immunosuppressive mutations survive to pass on their mutations to daughter cells, which may themselves mutate and undergo further selective pressure. This results in the tumor consisting of cells with decreased immunogenicity and can hardly be eliminated.[19] This phenomenon was proven to happen as a result of immunotherapies of cancer patients.[20]

Tumor evasion mechanisms

- CD8+ cytotoxic T cells are a fundamental element of anti-tumor immunity. Their TCR receptors recognise antigens presented by MHC class I and when bound, the Tc cell triggers its cytotoxic activity. MHC I are present on the surface of all nucleated cells. However, some cancer cells lower their MHC I expression and avoid being detected by the cytotoxic T cells.[21][22] This can be done by mutation of MHC I gene or by lowering the sensitivity to IFN-γ (which influences the surface expression of MHC I).[21][23] Tumor cells also have defects in antigen presentation pathway, what leads into down-regulation of tumor antigen presentations. Defects are for example in transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) or tapasin.[24] On the other hand, a complete loss of MHC I is a trigger for NK cells.[25] Tumor cells therefore maintain a low expression of MHC I.[21]

- Another way to escape cytotoxic T cells is to stop expressing molecules essential for co-stimulation of cytotoxic T cells, such as CD80 or CD86.[26][27]

- Tumor cells express molecules to induce apoptosis or to inhibit T lymphocytes:

- Tumor cells have gained resistance to effector mechanisms of NK and cytotoxic CD8+ T cell:

- by loss of gene expression or inhibition of apoptotic signal pathway molecules: APAF1, Caspase 8, Bcl-2-associated X protein (bax) and Bcl-2 homologous antagonist killer (bak).[citation needed]

- by induction of expression or overexpression of antiapoptotic molecules: Bcl-2, IAP or XIAP.[30][31]

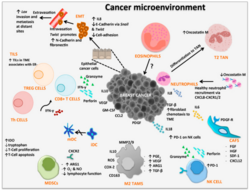

Tumor microenvironment

- Production of TGF-β by tumor cells and other cells (such as myeloid-derived suppressor cell) leads to conversion of CD4+ T cell into suppressive regulatory T cell (Treg)[32] by a contact dependent or independent stimulation. In a healthy tissue, functioning Tregs are essential to maintain self-tolerance. In a tumor, however, Tregs form an immunosuppressive microenvironment.[33]

- Tumor cells produce special cytokines (such as colony-stimulating factor) to produce myeloid-derived suppressor cell. These cells are heterogenous collection of cell types including precursors of dendritic cell, monocyte and neutrophil. MDSC have suppressive effects on T-lymphocytes, dendritic cells and macrophages. They produce immunosuppressive TGF-β and IL-10.[34][25]

- Another producer of suppressive TGF-β and IL-10 are tumor-associated macrophages, these macrophages have mostly phenotype of alternatively activated M2 macrophages. Their activation is promoted by TH type 2 cytokines (such as IL-4 and IL-13). Their main effects are immunosuppression, promotion of tumor growth and angiogenesis.[35]

- Tumor cells have non-classical MHC class I on their surface, for example HLA-G. HLA-G is inducer of Treg, MDSC, polarise macrophages into alternatively activated M2 and has other immunosuppressive effects on immune cells.[36]

Immunomodulation methods

Immune system is the key player in fighting cancer. As described above in mechanisms of tumor evasion, the tumor cells are modulating the immune response in their profit. It is possible to improve the immune response in order to boost the immunity against tumor cells.

- monoclonal anti-CTLA4 and anti-PD-1 antibodies are called immune checkpoint inhibitors:

- CTLA-4 is a receptor upregulated on the membrane of activated T lymphocytes, CTLA-4 CD80/86 interaction leads to switch off of T lymphocytes. By blocking this interaction with monoclonal anti CTLA-4 antibody we can increase the immune response. An example of approved drug is ipilimumab.

- PD-1 is also an upregulated receptor on the surface of T lymphocytes after activation. Interaction PD-1 with PD-L1 leads to switching off or apoptosis. PD-L1 are molecules which can be produced by tumor cells. The monoclonal anti-PD-1 antibody is blocking this interaction thus leading to improvement of immune response in CD8+ T lymphocytes. An example of approved cancer drug is nivolumab.[37]

- Chimeric Antigen Receptor T cell

- This CAR receptors are genetically engineered receptors with extracellular tumor specific binding sites and intracellular signalling domain that enables the T lymphocyte activation.[38]

- Cancer vaccine

- Vaccine can be composed of killed tumor cells, recombinant tumor antigens, or dendritic cells incubated with tumor antigens (dendritic cell-based cancer vaccine) [39]

Relationship to chemotherapy

Obeid et al.[40] investigated how inducing immunogenic cancer cell death ought to become a priority of cancer chemotherapy. He reasoned, the immune system would be able to play a factor via a 'bystander effect' in eradicating chemotherapy-resistant cancer cells.[41][42][43][2] However, extensive research is still needed on how the immune response is triggered against dying tumour cells.[2][44]

Professionals in the field have hypothesized that 'apoptotic cell death is poorly immunogenic whereas necrotic cell death is truly immunogenic'.[45][46][47] This is perhaps because cancer cells being eradicated via a necrotic cell death pathway induce an immune response by triggering dendritic cells to mature, due to inflammatory response stimulation.[48][49] On the other hand, apoptosis is connected to slight alterations within the plasma membrane causing the dying cells to be attractive to phagocytic cells.[50] However, numerous animal studies have shown the superiority of vaccination with apoptotic cells, compared to necrotic cells, in eliciting anti-tumor immune responses.[51][52][53][54][55]

Thus Obeid et al.[40] propose that the way in which cancer cells die during chemotherapy is vital. Anthracyclins produce a beneficial immunogenic environment. The researchers report that when killing cancer cells with this agent uptake and presentation by antigen presenting dendritic cells is encouraged, thus allowing a T-cell response which can shrink tumours. Therefore, activating tumour-killing T-cells is crucial for immunotherapy success.[2][56]

However, advanced cancer patients with immunosuppression have left researchers in a dilemma as to how to activate their T-cells. The way the host dendritic cells react and uptake tumour antigens to present to CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells is the key to success of the treatment.[2][57]

See also

References

- ↑ "The journey from discoveries in fundamental immunology to cancer immunotherapy". Cancer Cell 27 (4): 439–49. April 2015. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2015.03.007. PMID 25858803.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "De-novo and acquired resistance to immune checkpoint targeting". The Lancet. Oncology 18 (12): e731–e741. December 2017. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(17)30607-1. PMID 29208439.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Cancer immunoediting: from immunosurveillance to tumor escape". Nature Immunology 3 (11): 991–8. November 2002. doi:10.1038/ni1102-991. PMID 12407406.

- ↑ "Cancer; a biological approach. I. The processes of control". British Medical Journal 1 (5022): 779–86. April 1957. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.3356.779. PMID 13404306.

- ↑ "Cancer immunoediting from immune surveillance to immune escape". Immunology 121 (1): 1–14. May 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02587.x. PMID 17386080.

- ↑ "The immune response to tumors as a tool toward immunotherapy". Clinical & Developmental Immunology 2011: 894704. 2011. doi:10.1155/2011/894704. PMID 22190975.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "Categories of Tumor Antigens". Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine (6th ed.). BC Decker. 2003. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK12961/.

- ↑ "Human papillomavirus type 16 E6/E7-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes for adoptive immunotherapy of HPV-associated malignancies". Journal of Immunotherapy 36 (1): 66–76. January 2013. doi:10.1097/CJI.0b013e318279652e. PMID 23211628.

- ↑ "Different patterns of Epstein-Barr virus latency in endemic Burkitt lymphoma (BL) lead to distinct variants within the BL-associated gene expression signature". Journal of Virology 87 (5): 2882–94. March 2013. doi:10.1128/JVI.03003-12. PMID 23269792.

- ↑ "Oncogenic proteins as tumor antigens". Current Opinion in Immunology 8 (5): 637–42. October 1996. doi:10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80079-3. PMID 8902388.

- ↑ "Human Tumor Antigens Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow". Cancer Immunology Research 5 (5): 347–354. May 2017. doi:10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0112. PMID 28465452.

- ↑ "Oncofetal antigens as tumor markers in the cytologic diagnosis of effusions". Acta Cytologica 27 (6): 625–9. November 1983. PMID 6196931.

- ↑ "Alpha-fetoprotein in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after transcatheter arterial embolization". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 7 (6): 614–7. November 1992. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.1992.tb01495.x. PMID 1283085.

- ↑ "Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) in ovarian cancer: factors influencing its incidence and changes which occur in response to cytotoxic drugs". British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 83 (10): 753–9. October 1976. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1976.tb00739.x. PMID 990213.

- ↑ "Targeting of the non-mutated tumor antigen HER2/neu to mature dendritic cells induces an integrated immune response that protects against breast cancer in mice". Breast Cancer Research 14 (2): R39. March 2012. doi:10.1186/bcr3135. PMID 22397502.

- ↑ "EGF receptor variant III as a target antigen for tumor immunotherapy". Expert Review of Vaccines 7 (7): 977–85. September 2008. doi:10.1586/14760584.7.7.977. PMID 18767947.

- ↑ "The MAGE protein family and cancer". Current Opinion in Cell Biology 37: 1–8. December 2015. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2015.08.002. PMID 26342994.

- ↑ "The three Es of cancer immunoediting". Annual Review of Immunology 22 (1): 329–60. 2004-03-19. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104803. PMID 15032581.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "New insights into cancer immunoediting and its three component phases--elimination, equilibrium and escape". Current Opinion in Immunology 27: 16–25. April 2014. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2014.01.004. PMID 24531241.

- ↑ "NY-ESO-1-specific immunological pressure and escape in a patient with metastatic melanoma". Cancer Immunity 13: 12. 2013-07-15. PMID 23882157.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 "Immunotherapy: Hiding in plain sight: immune escape in the era of targeted T-cell-based immunotherapies". Nature Reviews. Clinical Oncology 14 (6): 333–334. June 2017. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.49. PMID 28397826.

- ↑ "Defective HLA class I antigen processing machinery in cancer". Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy 67 (6): 999–1009. June 2018. doi:10.1007/s00262-018-2131-2. PMID 29487978.

- ↑ "The Dark Side of IFN-γ: Its Role in Promoting Cancer Immunoevasion". International Journal of Molecular Sciences 19 (1): 89. December 2017. doi:10.3390/ijms19010089. PMID 29283429.

- ↑ "Immune evasion in cancer: Mechanistic basis and therapeutic strategies". Seminars in Cancer Biology. A broad-spectrum integrative design for cancer prevention and therapy 35 Suppl: S185–S198. December 2015. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2015.03.004. PMID 25818339.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "Cancer Immunoediting by Innate Lymphoid Cells". Trends in Immunology 40 (5): 415–430. May 2019. doi:10.1016/j.it.2019.03.004. PMID 30992189.

- ↑ "Low surface expression of B7-1 (CD80) is an immunoescape mechanism of colon carcinoma". Cancer Research 66 (4): 2442–50. February 2006. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1681. PMID 16489051.

- ↑ "Bladder cancer immunogenicity: expression of CD80 and CD86 is insufficient to allow primary CD4+ T cell activation in vitro". Clinical and Experimental Immunology 116 (1): 48–56. April 1999. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00857.x. PMID 10209504.

- ↑ "The role of CD95 and CD95 ligand in cancer". Cell Death and Differentiation 22 (4): 549–59. April 2015. doi:10.1038/cdd.2015.3. PMID 25656654.

- ↑ "CTLA-4 and PD-1 Pathways: Similarities, Differences, and Implications of Their Inhibition". American Journal of Clinical Oncology 39 (1): 98–106. February 2016. doi:10.1097/COC.0000000000000239. PMID 26558876.

- ↑ "Bcl2 family proteins in carcinogenesis and the treatment of cancer". Apoptosis 14 (4): 584–96. April 2009. doi:10.1007/s10495-008-0300-z. PMID 19156528.

- ↑ "X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein - a critical death resistance regulator and therapeutic target for personalized cancer therapy". Frontiers in Oncology 4: 197. 2014-07-28. doi:10.3389/fonc.2014.00197. PMID 25120954.

- ↑ "+ T cells". Journal of Translational Medicine 17 (1): 219. July 2019. doi:10.1186/s12967-019-1967-3. PMID 31288845.

- ↑ "The role of regulatory T cells in cancer" (in en). Immune Network 9 (6): 209–35. December 2009. doi:10.4110/in.2009.9.6.209. PMID 20157609.

- ↑ "The growing diversity and spectrum of action of myeloid-derived suppressor cells". European Journal of Immunology 40 (12): 3317–20. December 2010. doi:10.1002/eji.201041170. PMID 21110315.

- ↑ "Macrophage-Mediated Subversion of Anti-Tumour Immunity". Cells 8 (7): 747. July 2019. doi:10.3390/cells8070747. PMID 31331034.

- ↑ "Heterogeneity of HLA-G Expression in Cancers: Facing the Challenges" (in en). Frontiers in Immunology 9: 2164. 2018. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02164. PMID 30319626.

- ↑ "CTLA-4 and PD-1 Control of T-Cell Motility and Migration: Implications for Tumor Immunotherapy". Frontiers in Immunology 9: 2737. 2018-11-27. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02737. PMID 30542345.

- ↑ "An introduction to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell immunotherapy for human cancer". American Journal of Hematology 94 (S1): S3–S9. May 2019. doi:10.1002/ajh.25418. PMID 30680780.

- ↑ Cellular and molecular immunology. Elsevier. 2018. pp. 409. ISBN 978-0-323-47978-3.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 "Calreticulin exposure dictates the immunogenicity of cancer cell death". Nature Medicine 13 (1): 54–61. Jan 2007. doi:10.1038/nm1523. PMID 17187072.

- ↑ "Immunotherapy: bewitched, bothered, and bewildered no more". Science 305 (5681): 197–200. Jul 2004. doi:10.1126/science.1099688. PMID 15247468. Bibcode: 2004Sci...305..197S.

- ↑ "A better way for a cancer cell to die". The New England Journal of Medicine 354 (23): 2503–4. Jun 2006. doi:10.1056/NEJMcibr061443. PMID 16760453.

- ↑ "Cancer despite immunosurveillance: immunoselection and immunosubversion". Nature Reviews. Immunology 6 (10): 715–27. Oct 2006. doi:10.1038/nri1936. PMID 16977338.

- ↑ Immune Response Against Dying Tumor Cells. Advances in Immunology. 84. 2004. pp. 131–79. doi:10.1016/S0065-2776(04)84004-5. ISBN 978-0-12-022484-5.

- ↑ "Cell death in health and disease: the biology and regulation of apoptosis". Seminars in Cancer Biology 6 (1): 3–16. Feb 1995. doi:10.1006/scbi.1995.0002. PMID 7548839.

- ↑ "Apoptosis in the pathogenesis and treatment of disease". Science 267 (5203): 1456–62. Mar 1995. doi:10.1126/science.7878464. PMID 7878464. Bibcode: 1995Sci...267.1456T.

- ↑ "Death and anti-death: tumour resistance to apoptosis". Nature Reviews. Cancer 2 (4): 277–88. Apr 2002. doi:10.1038/nrc776. PMID 12001989.

- ↑ "The induction of tolerance by dendritic cells that have captured apoptotic cells". The Journal of Experimental Medicine 191 (3): 411–6. Feb 2000. doi:10.1084/jem.191.3.411. PMID 10662786.

- ↑ "Immune tolerance after delivery of dying cells to dendritic cells in situ". The Journal of Experimental Medicine 196 (8): 1091–7. Oct 2002. doi:10.1084/jem.20021215. PMID 12391020.

- ↑ "Classification of cell death: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death". Cell Death and Differentiation 12 (Suppl 2): 1463–7. Nov 2005. doi:10.1038/sj.cdd.4401724. PMID 16247491.

- ↑ "Mechanism of dichotomy between CD8+ responses elicited by apoptotic and necrotic cells". Cancer Immunity 13: 2. 2013. PMID 23390373.

- ↑ "Primary sterile necrotic cells fail to cross-prime CD8(+) T cells". Oncoimmunology 1 (7): 1017–1026. Oct 2012. doi:10.4161/onci.21098. PMID 23170250.

- ↑ "Efficient T cell activation via a Toll-Interleukin 1 Receptor-independent pathway". Immunity 24 (6): 787–99. Jun 2006. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2006.03.024. PMID 16782034.

- ↑ "Immunogenicity of apoptotic cells in vivo: role of antigen load, antigen-presenting cells, and cytokines". Journal of Immunology 163 (1): 130–6. Jul 1999. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.163.1.130. PMID 10384108.

- ↑ "Apoptotic, but not necrotic, tumor cell vaccines induce a potent immune response in vivo". International Journal of Cancer 103 (2): 205–11. Jan 2003. doi:10.1002/ijc.10777. PMID 12455034.

- ↑ "A 'good death' for tumor immunology". Nature Medicine 13 (1): 28–30. Jan 2007. doi:10.1038/nm0107-28. PMID 17206130.

- ↑ "Interferons, immunity and cancer immunoediting". Nature Reviews. Immunology 6 (11): 836–48. Nov 2006. doi:10.1038/nri1961. PMID 17063185.

KSF

KSF