Classic autism

Topic: Medicine

From HandWiki - Reading time: 25 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 25 min

| Autism | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Childhood autism, autistic disorder, (early) infantile autism, infantile psychosis, Kanner's autism, Kanner's syndrome |

| |

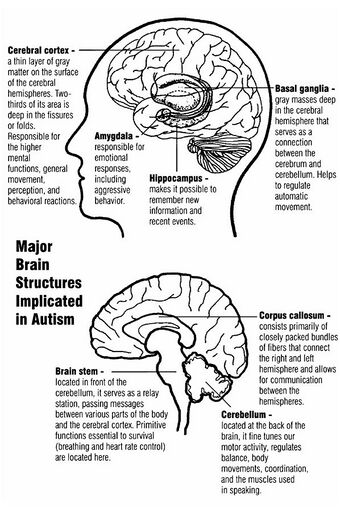

| Major brain structures implicated in autism | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, pediatrics, occupational medicine |

| Symptoms | Difficulties in social interaction, verbal and nonverbal communication; inflexible routines; narrow, restricted interests; repetitive body movements; unusual sensory responses |

| Complications | Social isolation, employment problems, stress, self-harm, suicide |

| Usual onset | By age 2 or 3 |

| Duration | Lifelong |

| Causes | Multifactorial, with many uncertain factors |

| Risk factors | Family history, certain genetic conditions |

| Diagnostic method | Based on behavior and developmental history |

| Differential diagnosis | Reactive attachment disorder, intellectual disability, schizophrenia[1] |

| Treatment | Occupational therapy, speech therapy, psychotropic medication[2][3] |

| Medication | Antipsychotics, antidepressants, stimulants (associated symptoms)[4] |

| Frequency | 24.8 million (2015)[5] |

Classic autism—also known as childhood autism, autistic disorder, or Kanner's syndrome—is a formerly diagnosed neurodevelopmental disorder first described by Leo Kanner in 1943. It is characterized by atypical and impaired development in social interaction and communication as well as restricted and repetitive behaviors, activities, and interests. These symptoms first appear in early childhood and persist throughout life.

Classic autism was last recognized as a diagnosis in the DSM-IV and ICD-10, and has been superseded by autism-spectrum disorder in the DSM-5 (2013) and ICD-11 (2022). Globally, classic autism was estimated to affect 24.8 million people as of 2015[update].[5]

Autism is likely caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors,[6] with genetic factors thought to heavily predominate.[7] Certain proposed environmental causes of autism have been met with controversy, such as the vaccine hypothesis that, although disproved, has negatively impacted vaccination rates among children.[8][9][10]

Since the DSM-5/ICD-11, the term "autism" more commonly refers to the broader autism spectrum.[11][12][13]

Characteristics

Autism is a highly variable neurodevelopmental disorder[14][15] whose symptoms first appear during infancy or childhood, and generally follow a steady course without remission.[16] Autistic people may be severely impaired in some respects but average, or even superior, in others.[17] Overt symptoms gradually begin after the age of six months and become established by age two or three years.[18] Some autistic children experience regression in their communication and social skills after reaching developmental milestones at a normal pace.[19][20] It was said to be distinguished by a characteristic triad of symptoms: impairments in social interaction, impairments in communication, and repetitive behavior.[15] Other aspects, such as atypical eating, are also common but are not essential for diagnosis.[21] Individual symptoms of autism occur in the general population and appear not to highly be associated, without a sharp line separating pathologically severe from common traits.[22]

Social development

Autistic people have social impairments and often lack the intuition about others that many people take for granted. Unusual social development becomes apparent early in childhood. Autistic infants show less attention to social stimuli, smile and look at others less often, and respond less to their own name. Autistic toddlers differ more strikingly from social norms; for example, they have less eye contact and turn-taking, and do not have the ability to use simple movements to express themselves, such as pointing at things.[23] Three- to five-year-old autistic children are less likely to exhibit social understanding, approach others spontaneously, imitate and respond to emotions, communicate nonverbally, and take turns with others. However, they do form attachments to their primary caregivers.[24] Most autistic children displayed moderately less attachment security than neurotypical children, although this difference disappears in children with higher mental development or less pronounced autistic traits.[25] Children with high-functioning autism have more intense and frequent loneliness compared to non-autistic peers, despite the common belief that autistic children prefer to be alone. Making and maintaining friendships often proves to be difficult for autistic people. For them, the quality of friendships, not the number of friends, predicts how lonely they feel. Functional friendships, such as those resulting in invitations to parties, may affect the quality of life more deeply.[26]

Communication

Differences in communication may be present from the first year of life, and may include delayed onset of babbling, unusual gestures, diminished responsiveness, and vocal patterns that are not synchronized with the caregiver. In the second and third years, autistic children have less frequent and less diverse babbling, consonants, words, and word combinations; their gestures are less often integrated with words. Autistic children are less likely to make requests or share experiences, and are more likely to simply repeat others' words (echolalia)[27] or reverse pronouns.[28] Deficits in joint attention may be present — for example, they may look at a pointing hand instead of the object to which the hand is pointing.[23] Autistic children may have difficulty with imaginative play and with developing symbols into language.[27] It is also thought that autistic and non-autistic adults produce different facial expressions, and that these differences could contribute to bidirectional communication difficulties.[29]

Repetitive behavior

Autistic individuals can display many forms of repetitive or restricted behavior, which the Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised (RBS-R) categorizes as follows.[30][31]

- Stereotyped behaviors: Repetitive movements, such as hand flapping, head rolling, or body rocking.

- Compulsive behaviors: Time-consuming behaviors intended to reduce the anxiety that an individual feels compelled to perform repeatedly or according to rigid rules, such as placing objects in a specific order, checking things, or handwashing.

- Sameness: Resistance to change; for example, insisting that the furniture not be moved or refusing to be interrupted.

- Ritualistic behavior: Unvarying pattern of daily activities, such as an unchanging menu or a dressing ritual.

- Restricted interests: Interests or fixations that are abnormal in theme or intensity of focus, such as preoccupation with a single television program, toy, or game.

No single repetitive or self-injurious behavior seems to be specific to autism, but autism appears to have an elevated pattern of occurrence and severity of these behaviors.[32]

Other symptoms

Autistic individuals may have symptoms that are independent of the diagnosis.[21] An estimated 0.5% to 10% of individuals with classic autism show unusual abilities, ranging from splinter skills such as the memorization of trivia to the extraordinarily rare talents of prodigious autistic savants.[33] Sensory abnormalities are found in over 90% of autistic people, and are considered core features by some,[21] although there is no good evidence that sensory symptoms differentiate autism from other developmental disorders.[34] An estimated 60–80% of autistic people have motor signs that include poor muscle tone, poor motor planning, and toe walking.[21]

Causes

It was presumed initially that there was a common cause at the genetic, cognitive, and neural levels for classic autism's characteristic triad of symptoms.[35] However, over time, there was increasing evidence that autism was instead a complex and highly heritable disorder whose core aspects have distinct causes which often co-occur.[35][36][37]

The exact causes of autism are unknown, but it is believed that both genetic and environmental factors play a role in its development.[38] Multiple studies have shown structural and functional atypicalities in the brains of autistic people.[39] Experiments have been conducted to determine if the degree of brain atypicality yields any correlation to the severity of autism. One study done by Elia et al. (2000) used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on the midsagittal area of the cerebrum, midbrain, cerebellar vermis, corpus callosum, and vermal lobules VI and VII to measure brain atypicalities in children with low-functioning autism. The results suggested that the midbrain structures correlate with certain developmental behavioral aspects such as motivation, mnemonic, and learning processes, though there is more research needed to confirm this.[40] Furthermore, many developmental processes may contribute to several types of brain atypicalities in autism; therefore, determining the link between such atypicalities and severity of autism proves difficult.[39]

Although theories regarding vaccines lack convincing scientific evidence, are biologically implausible,[41] and originated from a fraudulent study,[42] parental concern about a potential vaccine link with autism (and subsequent concern about ASD) has led to lower rates of childhood immunizations, outbreaks of previously controlled childhood diseases in some countries, and the preventable deaths of several children.[10][43]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of classic autism was based on behavioral symptoms, not cause or mechanism.[22][44]

The ICD-10 criteria for childhood autism postulate that abnormal or impaired development is evident before the age of 3 in receptive or expressive language used in social communication, development of selective social attachments or reciprocal social interactions, or functional and symbolic play. The children would also be required to exhibit six other symptoms from three macro-categories pertaining to qualitative impairment in social interactions, quantitative abnormalities in communication, and restricted/repetitive/stereotyped patterns of behavior, interests, and activities. ICD-10 differentiates high functioning and low-functioning autistic people by diagnosing the additional code of intellectual disability.[45]

Classification

Classic autism was listed as autistic disorder in the fourth edition of the American Psychiatric Association's diagnostic manual, as one of the five pervasive developmental disorders (PDDs).[46] However, the PDDs were collapsed into the single diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder in 2013,[46] and the WHO's diagnostic manual ICD-11 (which had listed it as childhood autism in its previous edition[47]) followed suit a few years later.[48] Classic autism was said to be characterized by widespread abnormalities of social interactions and communication, severely restricted interests, and highly repetitive behavior.[16]

Of the PDDs, Asperger syndrome was closest to classic autism in signs and likely causes; Rett syndrome and childhood disintegrative disorder share several signs with it, but were understood to potentially have unrelated causes; PDD not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS; also called atypical autism) was diagnosed when the criteria were not met for one of the other four PDDs.[49] People would usually attract a diagnosis of Asperger syndrome rather than classic autism if they showed no substantial delay in language development,[50] but early language ability was found to be a poor predictor of outcomes in adulthood.[51]

Low-functioning autism

Low-functioning autism (LFA) is a degree of autism marked by difficulties with social communication and interaction, unsafe or uncooperative behavior, and differences in social or emotional reciprocity. Sleep problems, stereotypical, and self-injurious behavior are also common symptoms.[39] LFA is not a recognized diagnosis in either the DSM or the ICD.

The term overlaps with severe autism and profound autism, as opposed to mild or moderate, which do not necessarily correlate with severe and profound levels of intellectual disability, where profound is the most severe level.[52][53]

Characterization

Those who display symptoms for LFA usually have "impairments in all the three areas of psychopathology: reciprocal social interaction, communication, and restricted, stereotyped, repetitive behaviour".[54]

Severe impairment of social skills can be seen in people with LFA.[55] This could include a lack of eye contact,[56] inadequate body language and a lack of emotional or physical response to others' behaviors and emotions. These social impairments can cause difficulty in relationships.[39]

Prognosis and management

This section is missing information about sources from autistic scholars, social activists, researchers, among others, would strengthen the bottom of this section. (June 2023) |

There is no known cure for autism,[2] and very little research has addressed long-term prognosis for classic autism.[58] Many autistic children lack social support, future employment opportunities or self-determination.[26]

No known medication relieves autism's core symptoms of social and communication impairments.[59] The main goals when treating autistic children are to lessen associated deficits and family distress, and to increase quality of life and functional independence. In general, higher IQs are correlated with greater responsiveness to treatment and improved treatment outcomes.[60] Treatments may include behavior analysis, speech and language therapy, occupational therapy, and psychosocial interventions.[59][61] Intensive, sustained special education programs and behavior therapy early in life often improve functioning and decrease symptom severity and maladaptive behaviors;[62] claims that intervention by around age three years is crucial are not substantiated.[63]

Therapy

Augmentative and alternative communication

Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) is used for autistic people who cannot communicate orally. People who have problems speaking may be taught to use other forms of communication, such as body language, computers, interactive devices, and pictures.[64] The Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) is a commonly used form of augmentative and alternative communication with children and adults who cannot communicate well orally. People are taught how to link pictures and symbols to their feelings, desires and observation, and may be able to link sentences together with the vocabulary that they form.[65]

Speech-language therapy

Speech-language therapy can help those with autism who need to develop or improve communication skills.[54] According to the organization Autism Speaks, "speech-language therapy is designed to coordinate the mechanics of speech with the meaning and social use of speech".[65] People with low-functioning autism may not be able to communicate with spoken words. Speech-language pathologists (SLP) may teach someone how to communicate more effectively with others or work on starting to develop speech patterns.[66] The SLP will create a plan that focuses on what the child needs.

Occupational therapy

Occupational therapy helps autistic children and adults learn everyday skills that help them with daily tasks, such as personal hygiene and movement. These skills are then integrated into their home, school, and work environments. Therapists will oftentimes help people learn to adapt their environment to their skill level.[67] An occupational therapist will create a plan based on a person's needs and desires and work with them to achieve their set goals.

Sensory integration therapy

Sensory integration therapy helps people with autism adapt to different kinds of sensory stimuli. Many with autism can be oversensitive to certain stimuli, such as lights or sounds, causing them to overreact. Others may not react to certain stimuli, such as someone speaking to them. Therapists will help create a plan that focuses on the type of stimulation the person needs integration with.[68]

Applied behavioral analysis (ABA)

Applied behavioral analysis (ABA) focuses on teaching adaptive behaviors like social skills, play skills, or communication skills[69][70] and diminishing problematic behaviors like eloping or self-injury[71] by creating a specialized plan that uses behavioral therapy techniques such as positive or negative reinforcement to encourage or discourage certain behaviors over-time.[72] ABA has been criticized by the neurodiversity movement.[73][74][75] It is recommended by the US Centers for Disease Control and the American Academy of Pediatrics,[76][77] while the UK's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence does not currently recommend its use for children and young people due to insufficient evidence of benefit.[78][79]

Medication

There are no medications specifically designed to treat autism. Medication is usually used for problems as a cause of autism, such as depression, anxiety, or behavioral problems.[80] Medicines are usually used after other alternative forms of treatment have failed.[81]

Education

File:Code of practice on provision of autism services.webm

Early, intensive ABA therapy has demonstrated effectiveness in enhancing communication and adaptive functioning in preschool children;[82] it is also well-established for improving the intellectual performance of that age group.[62][82] It is not known whether treatment programs for children lead to significant improvements after the children grow up,[62] and the limited research on the effectiveness of adult residential programs shows mixed results.[83]

Alternative medicine

Although many alternative therapies and interventions were used, few are supported by scientific studies.[84] Treatment approaches have little empirical support in quality-of-life contexts, and many programs focus on success measures that lack predictive validity and real-world relevance.[26] Some alternative treatments placed autistic individuals at risk.[85] For example, in 2005, a five-year-old child with autism was killed by botched chelation therapy (which is not recommended for autism as risks outweigh any potential benefits).[86][87][88]

Epidemiology

Globally, classic autism was understood to affect an estimated 24.8 million people as of 2015[update].[5] After it was recognised as a distinct disorder, reports of autism cases substantially increased, which was largely attributable to changes in diagnostic practices, referral patterns, availability of services, age at diagnosis, and public awareness[89][90] (particularly among women).[91]

Several other conditions were commonly seen in autistic children. They include:

- Intellectual disability. The percentage of autistic individuals who also met criteria for intellectual disability has been reported as anywhere from 25% to 70%, a wide variation illustrating the difficulty of assessing intelligence of individuals on the autism spectrum.[92] In comparison, for PDD-NOS the association with intellectual disability was much weaker,[93] and by definition, the diagnosis of Asperger's excluded intellectual disability.[94]

- Minor physical anomalies are significantly increased in the autistic population.[95]

- Preempted diagnoses. Although the DSM-IV ruled out the concurrent diagnosis of many other conditions along with autism, the full criteria for Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), Dyspraxia, Tourette syndrome, and other of these conditions were often present. As a result, modern ASD allows for these diagnoses.[96]

History

The Neo-Latin word autismus (English translation autism) was coined by the Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler in 1910 as he was defining symptoms of schizophrenia. He derived it from the Greek word autós (αὐτός, meaning "self"), and used it to mean morbid self-admiration, referring to "autistic withdrawal of the patient to his fantasies, against which any influence from outside becomes an intolerable disturbance".[98] The word autism first took its modern sense in 1938 when Hans Asperger of the Vienna University Hospital adopted Bleuler's terminology autistic psychopathy in a lecture in German about child psychology.[99] Asperger was investigating Asperger syndrome which, for various reasons, was not widely considered a separate diagnosis until 1981,[97] although both are now considered part of ASD. Leo Kanner of the Johns Hopkins Hospital first used autism in English to refer to classic autism when he introduced the label early infantile autism in a 1943 report.[28] Almost all the characteristics described in Kanner's first paper on the subject, notably "autistic aloneness" and "insistence on sameness", are still regarded as typical of the autistic spectrum of disorders.[36] Starting in the late 1960s, classic autism was established as a separate syndrome.[100]

It took until 1980 for the DSM-III to differentiate autism from childhood schizophrenia. In 1987, the DSM-III-R provided a checklist for diagnosing autism. In May 2013, the DSM-5 was released, updating the classification for pervasive developmental disorders. The grouping of disorders, including PDD-NOS, autism, Asperger syndrome, Rett syndrome, and CDD, has been removed and replaced with the general term of Autism Spectrum Disorder.[101]

References

- ↑ Clinical Assessment and Diagnosis in Social Work Practice. Oxford University Press, New York. 9 February 2006. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-19-516830-3. OCLC 466433183. https://books.google.com/books?id=y28kokLoe78C&pg=PA72.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Management of children with autism spectrum disorders". Pediatrics 120 (5): 1162–1182. November 2007. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-2362. PMID 17967921.

- ↑ "Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety in children with high-functioning autism: a meta-analysis". Pediatrics 132 (5): e1341–e1350. November 2013. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-1193. PMID 24167175.

- ↑ "An update on pharmacotherapy for autism spectrum disorder in children and adolescents". Current Opinion in Psychiatry 28 (2): 91–101. March 2015. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000132. PMID 25602248.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Vos, Theo et al. (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMID 27733282.

- ↑ "Autism risk factors: genes, environment, and gene-environment interactions". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 14 (3): 281–292. September 2012. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2012.14.3/pchaste. PMID 23226953.

- ↑ "Heritability of autism spectrum disorders: a meta-analysis of twin studies". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 57 (5): 585–595. May 2016. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12499. PMID 26709141.

- ↑ "Vaccines are not associated with autism: an evidence-based meta-analysis of case-control and cohort studies". Vaccine 32 (29): 3623–3629. June 2014. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.04.085. PMID 24814559.

- ↑ "Incidence of autism spectrum disorders: changes over time and their meaning". Acta Paediatrica 94 (1): 2–15. January 2005. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2005.tb01779.x. PMID 15858952.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Vaccines and autism:

- "Immunizations and autism: a review of the literature". The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. Le Journal Canadien des Sciences Neurologiques 33 (4): 341–346. November 2006. doi:10.1017/s031716710000528x. PMID 17168158.

- "Vaccines and autism: a tale of shifting hypotheses". Clinical Infectious Diseases 48 (4): 456–461. February 2009. doi:10.1086/596476. PMID 19128068.

- "A broken trust: lessons from the vaccine--autism wars". PLOS Biology 7 (5). May 2009. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000114. PMID 19478850.

- "Parents ask: Am I risking autism if I vaccinate my children?". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 39 (6): 962–963. June 2009. doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0739-y. PMID 19363650.

- "The age-old struggle against the antivaccinationists". The New England Journal of Medicine 364 (2): 97–99. January 2011. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1010594. PMID 21226573.

- ↑ Keating, Connor Tom; Hickman, Lydia; Leung, Joan; Monk, Ruth; Montgomery, Alicia; Heath, Hannah; Sowden, Sophie (2022-12-06). "Autism-related language preferences of English-speaking individuals across the globe: A mixed methods investigation" (in en). Autism Research 16 (2): 406–428. doi:10.1002/aur.2864. ISSN 1939-3792. PMID 36474364.

- ↑ "Autism". https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/conditions-and-diseases/mental-health-and-behavioural-conditions/autism.

- ↑ Autism: a new introduction to psychological theory and current debates. Francesca Happé ([New edition; Updated edition] ed.). Abingdon, Oxon. 2019. ISBN 978-1-315-10169-9. OCLC 1073035060.

- ↑ "Autism: many genes, common pathways?". Cell 135 (3): 391–395. October 2008. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.016. PMID 18984147.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Wozniak, Robert H.; Leezenbaum, Nina B.; Northrup, Jessie B.; West, Kelsey L.; Iverson, Jana M. (Jan 2017). "The Development of Autism Spectrum Disorders: Variability and Causal Complexity". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Cognitive Science 8 (1–2). doi:10.1002/wcs.1426. ISSN 1939-5078. PMID 27906524.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "F84. Pervasive developmental disorders". World Health Organization. 2007. http://apps.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icd10online/?gf80.htm+f84.

- ↑ Biopsychology (8th ed.). Boston, Massachusetts: Pearson. 2011. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-205-03099-6. OCLC 1085798897.

- ↑ "What are infant siblings teaching us about autism in infancy?". Autism Research 2 (3): 125–137. June 2009. doi:10.1002/aur.81. PMID 19582867.

- ↑ "Regression in autistic spectrum disorders". Neuropsychology Review 18 (4): 305–319. December 2008. doi:10.1007/s11065-008-9073-y. PMID 18956241.

- ↑ Barger, Brian D.; Campbell, Jonathan M. (2014), Patel, Vinood B.; Preedy, Victor R.; Martin, Colin R., eds., "Developmental Regression in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Implications for Clinical Outcomes" (in en), Comprehensive Guide to Autism (New York, NY: Springer): pp. 1473–1493, doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-4788-7_84, ISBN 978-1-4614-4788-7

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 "Advances in autism". Annual Review of Medicine 60: 367–380. 2009. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.60.053107.121225. PMID 19630577.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "The role of the neurobiologist in redefining the diagnosis of autism". Brain Pathology 17 (4): 408–411. October 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00103.x. PMID 17919126.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders: Volume Two: Assessment, Interventions, and Policy. 2 (4th ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. 2014. p. 301. ISBN 978-1-118-28220-5. OCLC 946133861. https://books.google.com/books?id=4yzqAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA301. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- ↑ "Early detection of core deficits in autism". Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews 10 (4): 221–233. 2004. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20046. PMID 15666338.

- ↑ "Autism and attachment: a meta-analytic review". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 45 (6): 1123–1134. September 2004. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.t01-1-00305.x. PMID 15257669.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 "Quality of Life for People with Autism: Raising the Standard for Evaluating Successful Outcomes". Child and Adolescent Mental Health 12 (2): 80–86. May 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1475-3588.2006.00432.x. PMID 32811109. http://kingwoodpsychology.com/recent_publications/camh_432.pdf. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "Early communication development and intervention for children with autism". Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews 13 (1): 16–25. 2007. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20134. PMID 17326115.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "Autistic disturbances of affective contact". Acta Paedopsychiatrica 35 (4): 100–136. 1943. PMID 4880460. Reprinted in "Autistic disturbances of affective contact". Acta Paedopsychiatrica 35 (4): 100–136. 1968. PMID 4880460.

- ↑ Keating, Connor Tom; Cook, Jennifer Louise (2020-07-01). "Facial Expression Production and Recognition in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Shifting Landscape" (in en). Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. Autism Spectrum Disorder Across the Lifespan: Part II 29 (3): 557–571. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2020.02.006. ISSN 1056-4993. PMID 32471602.

- ↑ "The Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised: independent validation in individuals with autism spectrum disorders". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 37 (5): 855–866. May 2007. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0213-z. PMID 17048092.

- ↑ Tian, Junbin; Gao, Xuping; Yang, Li (2022). "Repetitive Restricted Behaviors in Autism Spectrum Disorder: From Mechanism to Development of Therapeutics". Frontiers in Neuroscience 16. doi:10.3389/fnins.2022.780407. ISSN 1662-453X. PMID 35310097.

- ↑ "Varieties of repetitive behavior in autism: comparisons to mental retardation". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 30 (3): 237–243. June 2000. doi:10.1023/A:1005596502855. PMID 11055459.

- ↑ "The savant syndrome: an extraordinary condition. A synopsis: past, present, future". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 364 (1522): 1351–1357. May 2009. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0326. PMID 19528017.

- ↑ "Annotation: what do we know about sensory dysfunction in autism? A critical review of the empirical evidence". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 46 (12): 1255–1268. December 2005. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01431.x. PMID 16313426.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "The 'fractionable autism triad': a review of evidence from behavioural, genetic, cognitive and neural research". Neuropsychology Review 18 (4): 287–304. December 2008. doi:10.1007/s11065-008-9076-8. PMID 18956240.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 "Time to give up on a single explanation for autism". Nature Neuroscience 9 (10): 1218–1220. October 2006. doi:10.1038/nn1770. PMID 17001340.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 "Autism: highly heritable but not inherited". Nature Medicine 13 (5): 534–536. May 2007. doi:10.1038/nm0507-534. PMID 17479094.

- ↑ "Autism Spectrum Disorder: Fact Sheet". http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/autism/detail_autism.htm.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 Brambilla, P (2003). "Brain anatomy and development in autism: Review of structural MRI studies". Brain Research Bulletin 61 (6): 557–569. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2003.06.001. PMID 14519452.

- ↑ Elia, M; Ferri, R; Musumeci, S; Panerai, S; Bottitta, M; Scuderi, C (2000). "Clinical Correlates of Brain Morphometric Features of Subjects With Low-Functioning Autistic Disorder". Journal of Child Neurology 15 (8): 504–508. doi:10.1177/088307380001500802. PMID 10961787.

- ↑ "Vaccines and autism: a tale of shifting hypotheses". Clinical Infectious Diseases 48 (4): 456–461. February 2009. doi:10.1086/596476. PMID 19128068.

- ↑ "Wakefield's article linking MMR vaccine and autism was fraudulent". BMJ 342. January 2011. doi:10.1136/bmj.c7452. PMID 21209060. http://www.bmj.com/content/342/bmj.c7452.full.

- ↑ "Measles outbreak in Dublin, 2000". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 22 (7): 580–584. July 2003. doi:10.1097/00006454-200307000-00002. PMID 12867830.

- ↑ "Diagnosis of autism". BMJ 327 (7413): 488–493. August 2003. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7413.488. PMID 12946972.

- ↑ Strunecká, A (2011). Cellular and molecular biology of autism spectrum disorders. Bentham e Books. pp. 4–5.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 "The Diagnosis of Autism: From Kanner to DSM-III to DSM-5 and Beyond". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 51 (12): 4253–4270. December 2021. doi:10.1007/s10803-021-04904-1. PMID 33624215.

- ↑ "ICD-10 Version:2016". https://icd.who.int/browse10/2016/en#/F84.0.

- ↑ "World Health Organisation updates classification of autism in the ICD-11 – Autism Europe" (in en-US). https://www.autismeurope.org/blog/2018/06/21/world-health-organisation-updates-classification-of-autism-in-the-icd-11/.

- ↑ "Autism and autism spectrum disorders: diagnostic issues for the coming decade". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 50 (1–2): 108–115. January 2009. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02010.x. PMID 19220594.

- ↑ "Diagnostic criteria for 299.00 Autistic Disorder". Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV (4th ed.). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association. 2000. ISBN 978-0-89042-025-6. OCLC 768475353. http://cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/hcp-dsm.html.

- ↑ "Outcome in High-Functioning Adults with Autism with and Without Early Language Delays: Implications for the Differentiation Between Autism and Asperger Syndrome" (in en). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 33 (1): 3–13. 2003-02-01. doi:10.1023/A:1022270118899. ISSN 1573-3432. PMID 12708575.

- ↑ Coleman, Mary; Gillberg, Christopher (2011). The Autisms. Oxford University Press. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-19-999629-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=9id-BwAAQBAJ&pg=PT192. "For extremely low-functioning children with clinically estimated IQs of about 30 or under, [a test is suitable for those with] autism with severe and profound levels of mental retardation/intellectual disability."

- ↑ Thurm, Audrey (30 July 2019). "State of the Field: Differentiating Intellectual Disability From Autism Spectrum Disorder". Frontiers in Psychiatry 10: 526. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00526. ISSN 1664-0640. PMID 31417436.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 "What is Autism, Asperger Syndrome, and Pervasive Developmental Disorders?". https://www.usautism.org/definitions.html.

- ↑ "Autism (Autism Spectrum Disorder (or known as ASD): Symptoms of Autism Spectrum Disorder" (in en). 29 April 2020. https://otsimo.com/en/autism-spectrum-disorder-definitive-guide/#symptoms-of-autism-spectrum-disorder.

- ↑ "Why do those with autism avoid eye contact? Imaging studies reveal overactivation of subcortical brain structures in response to direct gaze" (in en). https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/06/170615213252.htm.

- ↑ "Opening a window to the autistic brain". PLOS Biology 2 (8). August 2004. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020267. PMID 15314667.

- ↑ "Trajectory of development in adolescents and adults with autism". Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews 10 (4): 234–247. 2004. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20038. PMID 15666341.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 CDC (2022-03-09). "Treatment and Intervention Services for Autism Spectrum Disorder" (in en-us). https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/treatment.html.

- ↑ "Meta-analysis of Early Intensive Behavioral Intervention for children with autism". Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology 38 (3): 439–450. May 2009. doi:10.1080/15374410902851739. PMID 19437303.

- ↑ "Management of children with autism spectrum disorders". Pediatrics 120 (5): 1162–82. November 2007. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-2362. PMID 17967921.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 "Evidence-based comprehensive treatments for early autism". Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology 37 (1): 8–38. January 2008. doi:10.1080/15374410701817808. PMID 18444052.

- ↑ "Systematic review of early intensive behavioral interventions for children with autism". American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 114 (1): 23–41. January 2009. doi:10.1352/2009.114:23-41. PMID 19143460.

- ↑ "Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC)". http://www.asha.org/public/speech/disorders/AAC/.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 "What Treatments are Available for Speech, Language and Motor Issues?". https://www.autismspeaks.org/what-autism/treatment/what-treatments-are-available-speech-language-and-motor-impairments.

- ↑ "Speech and Language Therapy". http://www.autismeducationtrust.org.uk/good-practice/written-for-you/parents-and-cares/pc-speech-and-language-therapy.aspx.

- ↑ "Occupational Therapy's Role with Autism". https://www.aota.org/-/media/Corporate/Files/AboutOT/Professionals/WhatIsOT/CY/Fact-Sheets/Autism%20fact%20sheet.ashx.

- ↑ Smith, M; Segal, J; Hutman, T, Autism Spectrum Disorders

- ↑ "Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA): What is ABA?". 16 June 2011. http://www.autismpartnership.com/applied-behavior-analysis.

- ↑ Matson, Johnny; Hattier, Megan; Belva, Brian (January–March 2012). "Treating adaptive living skills of persons with autism using applied behavior analysis: A review". Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 6 (1): 271–276. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2011.05.008.

- ↑ Summers, Jane; Sharami, Ali; Cali, Stefanie; D'Mello, Chantelle; Kako, Milena; Palikucin-Reljin, Andjelka; Savage, Melissa; Shaw, Olivia et al. (November 2017). "Self-Injury in Autism Spectrum Disorder and Intellectual Disability: Exploring the Role of Reactivity to Pain and Sensory Input". Brain Sci 7 (11): 140. doi:10.3390/brainsci7110140. PMID 29072583.

- ↑ "Applied Behavioral Strategies - Getting to Know ABA". http://www.appliedbehavioralstrategies.com/what-is-aba.html.

- ↑ Leaf, Justin B.; Cihon, Joseph H.; Leaf, Ronald; McEachin, John; Liu, Nicholas; Russell, Noah; Unumb, Lorri; Shapiro, Sydney et al. (2022-06-01). "Concerns About ABA-Based Intervention: An Evaluation and Recommendations" (in en). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 52 (6): 2838–2853. doi:10.1007/s10803-021-05137-y. ISSN 1573-3432. PMID 34132968.

- ↑ Ne'eman, Ari (2021-07-01). "When Disability Is Defined by Behavior, Outcome Measures Should Not Promote "Passing"" (in en). AMA Journal of Ethics 23 (7): 569–575. doi:10.1001/amajethics.2021.569. ISSN 2376-6980. PMID 34351268. PMC 8957386. https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/when-disability-defined-behavior-outcome-measures-should-not-promote-passing/2021-07.

- ↑ Schuck, Rachel K.; Tagavi, Daina M.; Baiden, Kaitlynn M. P.; Dwyer, Patrick; Williams, Zachary J.; Osuna, Anthony; Ferguson, Emily F.; Jimenez Muñoz, Maria et al. (2022-10-01). "Neurodiversity and Autism Intervention: Reconciling Perspectives Through a Naturalistic Developmental Behavioral Intervention Framework" (in en). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 52 (10): 4625–4645. doi:10.1007/s10803-021-05316-x. ISSN 1573-3432. PMID 34643863.

- ↑ CDC (2024-07-18). "Treatment and Intervention for Autism Spectrum Disorder" (in en-us). https://www.cdc.gov/autism/treatment/index.html.

- ↑ Hyman, Susan L.; Levy, Susan E.; Myers, Scott M.; COUNCIL ON CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES, SECTION ON DEVELOPMENTAL AND BEHAVIORAL PEDIATRICS; Kuo, Dennis Z.; Apkon, Susan; Davidson, Lynn F.; Ellerbeck, Kathryn A. et al. (2020-01-01). "Identification, Evaluation, and Management of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder". Pediatrics 145 (1): e20193447. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-3447. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 31843864.

- ↑ "Autism spectrum disorder in adults: diagnosis and management – Appendix A: Summary of evidence from surveillance (all 3 guidelines)". 2021-06-14. pp. 85–86. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg142/evidence/appendix-a-summary-of-evidence-from-surveillance-all-3-guidelines-pdf-9140525966. "The guideline on managing autism in children and young [people] does not include recommendations on applied behavioural analysis and the new evidence suggested that an update in this area is not necessary."

- ↑ "How we made the decision | Evidence | Autism spectrum disorder in under 19s: recognition, referral and diagnosis | Guidance | NICE". 2011-09-28. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg128/resources/surveillance-report-2016-autism-spectrum-disorder-in-under-19s-recognition-referral-and-diagnosis-2011-nice-guideline-cg128-and-autism-spectrum-disorder-in-under-19s-support-and-management-2013-nice--2660567437/chapter/How-we-made-the-decision?tab=evidence. "Consultees felt that applied behavioural analysis (ABA) should be recommended by NICE as an intervention to manage autism in children and young people. However, it was noted that high-quality evidence was not found for ABA during guideline development or surveillance review. Most of the evidence for ABA comes from single-case experimental designs, which have limitations like the restriction of generalisation to wider population and the high risk of publication bias. This area will be considered again at the next surveillance review of the guideline."

- ↑ National Institute of Mental Health. "Medications for Autism". http://psychcentral.com/lib/medications-for-autism/.

- ↑ Pope, J; Volkmar, Fred R. (November 14, 2014). Medicines for Autism.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 "Outcome of comprehensive psycho-educational interventions for young children with autism". Research in Developmental Disabilities 30 (1): 158–178. 2009. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2008.02.003. PMID 18385012.

- ↑ "Effects of a model treatment approach on adults with autism". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 33 (2): 131–140. April 2003. doi:10.1023/A:1022931224934. PMID 12757352.

- ↑ "Autism from developmental and neuropsychological perspectives". Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 2: 327–355. 2006. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095210. PMID 17716073.

- ↑ "Characterizing the Interplay Between Autism Spectrum Disorder and Comorbid Medical Conditions: An Integrative Review". Frontiers in Psychiatry 9: 751. 2019. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00751. PMID 30733689.

- ↑ "Complementary and alternative medicine treatments for children with autism spectrum disorders". Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America 17 (4): 803–20, ix. October 2008. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2008.06.004. PMID 18775371.

- ↑ "Deaths resulting from hypocalcemia after administration of edetate disodium: 2003-2005". Pediatrics 118 (2): e534–e536. August 2006. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-0858. PMID 16882789. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/118/2/e534.

- ↑ "Chelation for autism spectrum disorder (ASD)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5). May 2015. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010766. PMID 26106752.

- ↑ "Epidemiology of pervasive developmental disorders". Pediatric Research 65 (6): 591–598. June 2009. doi:10.1203/PDR.0b013e31819e7203. PMID 19218885.

- ↑ "Three Reasons Not to Believe in an Autism Epidemic". Current Directions in Psychological Science 14 (2): 55–58. April 2005. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00334.x. PMID 25404790.

- ↑ "Time trends in autism diagnosis over 20 years: a UK population-based cohort study". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 63 (6): 674–682. August 2021. doi:10.1111/jcpp.13505. PMID 34414570. "The figure starkly illustrates an overall 787% increase in recorded incidence of autism diagnosis over 20 years.".

- ↑ "Learning in autism". Learning and Memory: A Comprehensive Reference. 2. Elsevier. 2008. pp. 759–772. doi:10.1016/B978-012370509-9.00152-2. ISBN 978-0-12-370504-4. OCLC 775005136. http://psych.wisc.edu/lang/pdf/Dawson_AutisticLearning.pdf. Retrieved 26 July 2008.

- ↑ "Pervasive developmental disorders in preschool children". JAMA 285 (24): 3093–3099. June 2001. doi:10.1001/jama.285.24.3093. PMID 11427137.

- ↑ Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association. 2000. p. 80.

- ↑ "Minor physical anomalies in autism: a meta-analysis". Molecular Psychiatry 15 (3): 300–307. March 2010. doi:10.1038/mp.2008.75. PMID 18626481.

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association (2013). "Autism Spectrum Disorder, 299.00 (F84.0)". Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Publishing. pp. 50–59.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 "The history of autism". European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 13 (4): 201–208. August 2004. doi:10.1007/s00787-004-0363-5. PMID 15365889.

- ↑ "Eugen Bleuler's concepts of psychopathology". History of Psychiatry 15 (59 Pt 3): 361–366. September 2004. doi:10.1177/0957154X04044603. PMID 15386868. The quote is a translation of Bleuler's 1910 original.

- ↑ "Das psychisch abnormale Kind" (in de). Wien Klin Wochenschr 51: 1314–1317. 1938.

- ↑ "Modern views of autism". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 48 (8): 503–505. September 2003. doi:10.1177/070674370304800801. PMID 14574825.

- ↑ "Autism at 70--redrawing the boundaries". The New England Journal of Medicine 369 (12): 1089–1091. September 2013. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1306380. PMID 24047057. http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/daf7/ff077eb74aa9a1afdc70c101581e1b128ca3.pdf.

External links

| Library resources about Classic autism |

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

Template:Nonverbal communication

|

KSF

KSF