Cognitive therapies for dementia

Topic: Medicine

From HandWiki - Reading time: 6 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 6 min

Psychological therapies for dementia are starting to gain some momentum.[when?] Improved clinical assessment in early stages of Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia, increased cognitive stimulation of the elderly, and the prescription of drugs to slow cognitive decline have resulted in increased detection in the early stages.[1][2][3] Although the opinions of the medical community are still apprehensive to support cognitive therapies in dementia patients, recent international studies have started to create optimism.[4]

Classification

Psychological therapies which are considered as potential treatments for dementia include music therapy,[5] reminiscence therapy,[6] cognitive reframing for caretakers,[7] validation therapy,[8] and mental exercise.[9] Interventions may be used in conjunction with pharmaceutical treatment and can be classified within behavior, emotion, cognition or stimulation oriented approaches. Research on efficacy is reduced.[10]

Behavioral interventions

Behavioral interventions attempt to identify and reduce the antecedents and consequences of problem behaviors. This approach has not shown success in the overall functioning of patients,[11] but can help to reduce some specific problem behaviors, such as incontinence.[12] There is still a lack of high quality data on the effectiveness of these techniques in other behavior problems such as wandering.[13][14]

Emotion-oriented interventions

Emotion-oriented interventions include reminiscence therapy, validation therapy, supportive psychotherapy, sensory integration or snoezelen, and simulated presence therapy. Supportive psychotherapy has received little or no formal scientific study, but some clinicians find it useful in helping mildly impaired patients adjust to their illness.[10] Reminiscence therapy (RT) involves the discussion of past experiences individually or in group, many times with the aid of photographs, household items, music and sound recordings, or other familiar items from the past. Although there are few quality studies on the effectiveness of RT it may be beneficial for cognition and mood.[15][needs update] Simulated presence therapy (SPT) is based on attachment theories and is normally carried out playing a recording with voices of the closests relatives of the patient. There is preliminary evidence indicating that SPT may reduce anxiety and challenging behaviors.[16][17] Finally, validation therapy is based on acceptance of the reality and personal truth of another's experience, while sensory integration is based on exercises aimed to stimulate senses. There is little evidence to support the usefulness of these therapies.[18][19]

Cognition-oriented treatments

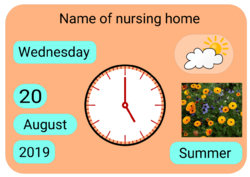

The aim of cognition-oriented treatments, which include reality orientation and cognitive retraining is the restoration of cognitive deficits. Reality orientation consists in the presentation of information about time, place or person in order to ease the understanding of the person about its surroundings and his place in them, for example using an orientation board. On the other hand, cognitive retraining tries to improve impaired capacities by exercitation of mental abilities. Both have shown some efficacy improving cognitive capacities,[20][21] although in some works these effects were transient and negative effects, such as frustration, have also been reported.[10] Most of the programs inside this approach are fully or partially computerized and others are fully paper based such as the Cognitive Retention Therapy method.[22][23]

Stimulation-oriented treatments

Stimulation-oriented treatments include art, music and pet therapies, exercise, and any other kind of recreational activities for patients. Stimulation has modest support for improving behavior, mood, and, to a lesser extent, function. Nevertheless, as important as these effects are, the main support for the use of stimulation therapies is the improvement in the patient daily life routine they suppose.[10]

A study published in 2006 tested the effects of Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (CST) on the demented elderly’s quality of life. The researchers looked at the effect of CST on cognitive function, the effect of improved cognitive function on quality of life, then the link between the three (CST, cognition, and QoL). The study found an improvement in cognitive function from the CST treatment, as measured by the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS-Cog), as well as an improvement in quality of life self-reported by the participants using the Quality of Life-AD measure. The study then used regression models to explain the correlation between the CST therapy and quality of life to see if the improved cognitive function was the primary mediating factor for the improved quality of life. The models supported the correlation and proposed that it was the improved cognition more than other factors (such as reduced depression symptoms and less anxiety) that led to the participants reporting back that they had a better quality of life (with significant improvements especially in energy level, memory, relationship with significant other, and ability to do chores.) [24]

Another study that was done in 2010 by London College that tested the efficacy of the Cognitive Stimulation Therapy. Participants were tested using a Mini Mental State Examination to test their level of cognitive ability and see if they qualified as a demented patient to be included in the study. The participants had to have no other health problems allowing for the experiment to have accurate internal validity. The results clearly showed that those who were given the Cognitive Stimulation Therapy did significantly better on all memory tasks than those that did not receive the therapy. Out of the eleven memory tasks that were given ten of the memory tasks were improved by the therapeutic group. This is another study that supports the efficacy of CST, demonstrating that the elderly that have dementia greatly benefit from this treatment.. Just like it was tested in the 2006 study,[24] the improvement of the participants' cognitive abilities can ultimately improve their daily lives since it helps with social influences being able to speak, remember words etc.[25]

In July 2015 UK NHS trials were reported of a robot seal from Japan being in the management of distressed and disturbed behaviour in dementia patients. "Paro", which has some artificial intelligence has the ability to "learn" and remember its own name. It can also learn the behaviour that results in a pleasing stroking response and repeat it. The robot was being evaluated in a joint project involving Sheffield Health and Social Care NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Sheffield.[26]

Psychological approaches to neuropsychiatric symptoms

Out of a number of psychological therapies examined, only behavior management therapy has demonstrated effectiveness in treating dementia-associated neuropsychiatric symptoms. [27]

References

- ↑ "NGC - NGC Summary". http://www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?ss=15&doc_id=2816&nbr=2042.

- ↑ "Early Alzheimer's disease diagnosis gives hope: detection in initial stages could slow progression, perhaps lead to prevention". http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0857/is_11_12/ai_n17215917.

- ↑ Satcher David (1999). "Alzheimer's Disease Mental Health: A report of the Surgeon General". http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/mentalhealth/chapter5/sec4.html.

- ↑ "[Cognitive training in Alzheimer's dementia]" (in de). Der Nervenarzt 77 (5): 549–57. May 2006. doi:10.1007/s00115-005-1998-2. PMID 16228161.

- ↑ van der Steen, Jenny T.; Smaling, Hanneke Ja; van der Wouden, Johannes C.; Bruinsma, Manon S.; Scholten, Rob Jpm; Vink, Annemiek C. (23 July 2018). "Music-based therapeutic interventions for people with dementia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 7: CD003477. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003477.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 30033623.

- ↑ Woods, Bob; O'Philbin, Laura; Farrell, Emma M.; Spector, Aimee E.; Orrell, Martin (1 March 2018). "Reminiscence therapy for dementia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 3: CD001120. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001120.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 29493789.

- ↑ "Cognitive reframing for carers of people with dementia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (11): CD005318. November 2011. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005318.pub2. PMID 22071821.

- ↑ "Validation therapy for dementia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD001394. 2003. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001394. PMID 12917907.

- ↑ "Cognitive stimulation to improve cognitive functioning in people with dementia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2 (2): CD005562. February 2012. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005562.pub2. PMID 22336813.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 "Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias, Second Edition". Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Alzheimer's disease and Other Dementias. 1. American Psychiatric Association. October 2007. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890423967.152139. ISBN 978-0-89042-336-3. http://www.psychiatryonline.com/pracGuide/loadGuidelinePdf.aspx?file=AlzPG101007. Retrieved 2007-12-28.

- ↑ "Cognitive rehabilitation combined with drug treatment in Alzheimer's disease patients: a pilot study". Clinical Rehabilitation 19 (8): 861–9. December 2005. doi:10.1191/0269215505cr911oa. PMID 16323385.

- ↑ "Practice parameter: management of dementia (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology 56 (9): 1154–66. May 2001. doi:10.1212/WNL.56.9.1154. PMID 11342679.

- ↑ "Non-pharmacological interventions for wandering of people with dementia in the domestic setting". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD005994. January 2007. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005994.pub2. PMID 17253573.

- ↑ "Effectiveness and acceptability of non-pharmacological interventions to reduce wandering in dementia: a systematic review". International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 22 (1): 9–22. January 2007. doi:10.1002/gps.1643. PMID 17096455.

- ↑ "Reminiscence therapy for dementia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD001120. April 2005. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001120.pub2. PMID 15846613.

- ↑ "Using simulated presence therapy with people with dementia". Aging & Mental Health 6 (1): 77–81. February 2002. doi:10.1080/13607860120101095. PMID 11827626.

- ↑ "Evaluation of Simulated Presence: a personalized approach to enhance well-being in persons with Alzheimer's disease". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 47 (4): 446–52. April 1999. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb07237.x. PMID 10203120.

- ↑ "Validation therapy for dementia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD001394. 2003. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001394. PMID 12917907.

- ↑ "Snoezelen for dementia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD003152. 2002. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003152. PMID 12519587.

- ↑ "WITHDRAWN: Reality orientation for dementia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD001119. July 2007. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001119.pub2. PMID 17636652.

- ↑ "Efficacy of an evidence-based cognitive stimulation therapy programme for people with dementia: randomised controlled trial". The British Journal of Psychiatry 183 (3): 248–54. September 2003. doi:10.1192/bjp.183.3.248. PMID 12948999.

- ↑ Early Intervention for Alzheimer's Disease

- ↑ Section C2 Alzheimer's Society of Canada

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "Improved quality of life and cognitive stimulation therapy in dementia". Aging & Mental Health 10 (3): 219–26. May 2006. doi:10.1080/13607860500431652. PMID 16777649.

- ↑ "Epigenetic regulation of caloric restriction in aging". BMC Medicine 9 (1): 98. August 2011. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-9-98. PMID 21867551.

- ↑ Griffiths, Andrew (2014-07-08). "How Paro the robot seal is being used to help UK dementia patients | Andrew Griffiths". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2014/jul/08/paro-robot-seal-dementia-patients-nhs-japan.

- ↑ "Systematic review of psychological approaches to the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia". The American Journal of Psychiatry 162 (11): 1996–2021. November 2005. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.1996. PMID 16263837.

KSF

KSF