Compartment syndrome

Topic: Medicine

From HandWiki - Reading time: 16 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 16 min

| Compartment syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

| A forearm following emergency surgery for acute compartment syndrome | |

| Specialty | Orthopedics |

| Symptoms | Pain, numbness, pallor, decreased ability to move the affected limb[1] |

| Complications | Acute: Volkmann's contracture[2] |

| Types | Acute, chronic[1] |

| Causes |

|

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, compartment pressure[5][1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Cellulitis, tendonitis, deep vein thrombosis, venous insufficiency[3] |

| Treatment |

|

Compartment syndrome is a serious medical condition in which increased pressure within a body compartment compromises blood flow and tissue function, potentially leading to permanent damage if not promptly treated.[5][6][7] There are two types: acute and chronic.[8] Acute compartment syndrome can lead to a loss of the affected limb due to tissue death.[6][9]

Symptoms of acute compartment syndrome (ACS) include severe pain, decreased blood flow, decreased movement, numbness, and a pale limb.[5] It is most often due to physical trauma, like a bone fracture (up to 75% of cases) or a crush injury.[3][6] It can also occur after blood flow returns following a period of poor circulation.[4] Diagnosis is clinical, based on symptoms, not a specific test.[5] However, it may be supported by measuring the pressure inside the compartment.[5] It is classically described by pain out of proportion to the injury, or pain with passive stretching of the muscles.[5] Normal compartment pressure should be 12–18 mmHg; higher is abnormal and needs treatment.[9] Treatment is urgent surgery to open the compartment.[5] If not treated within six hours, it can cause permanent muscle or nerve damage.[5][10]

Chronic compartment syndrome (CCS), or chronic exertional compartment syndrome, causes pain with exercise.[1] The pain fades after activity stops.[11] Other symptoms may include numbness.[1] Symptoms usually resolve with rest.[1] Running and biking commonly trigger CCS.[1] This condition generally does not cause permanent damage.[1] Similar conditions include stress fractures and tendinitis.[1] Treatment may include physical therapy or, if that fails, surgery.[1]

ACS occurs in about 1–10% of those with a tibial shaft fracture.[6] It is more common in males and those under 35, due to trauma.[3][12] German surgeon Richard von Volkmann first described compartment syndrome in 1881.[5] Delayed treatment can cause pain, nerve damage, cosmetic changes, and Volkmann's contracture.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Compartment syndrome usually presents within a few hours of an inciting event, but it may present anytime up to 48 hours after.[6] The earliest symptom is a tense, "wood-like" feeling in the affected limb.[5][6] There may also be decreased pulses, paralysis, and pallor, along with paresthesia.[13] Usually, NSAIDs cannot relieve the pain.[14] High compartment pressure may limit the range of motion.[15] In acute compartment syndrome, the pain will not be relieved with rest.[8] In chronic exertional compartment syndrome, the pain will dissipate with rest.[16]

Acute

There are five signs and symptoms of acute compartment syndrome.[6] They are known as the "5 Ps": pain, pallor, decreased pulse, paresthesia, and paralysis.[6] Pain and paresthesia are the early symptoms of compartment syndrome.[17][6]

Common symptoms are:

- Pain: A person may feel pain greater than the exam findings.[6] This pain may not be relieved by strong painkillers, including opioids like morphine.[18] It may be due to nerve damage from ischemia.[6] A person may experience pain disproportionate to the findings of the physical examination.[19] The pain is aggravated by passively stretching the muscle group within the compartment.[19] However, such pain may disappear in the late stages of compartment syndrome.[17]

- Paresthesia (altered sensation): A person may complain of "pins and needles," numbness, and a tingling sensation. This may progress to loss of sensation (anesthesia) if no intervention is made.[17]

Uncommon symptoms are:

- Paralysis: Paralysis of the limb is a rare, late finding.[5] It may indicate both a nerve or muscular lesion.[17]

- Pallor: Pallor describes the loss of color to the affected limb.[8] Other skin changes can include swelling, stiffness, or cold temperature.[9]

- Pulselessness: A lack of pulse rarely occurs in patients, as pressures that cause compartment syndrome are often lower than arterial pressures.[5] Absent pulses occur only with arterial injury or late-stage compartment syndrome, when pressures are very high.[5]

Chronic

Chronic exertional compartment syndrome (CECS) may cause pain, tightness, cramps, weakness, and numbness.[20] This pain can last for months or even years, but rest may relieve it.[21] There may also be mild weakness in the affected area.[11]

Exercise causes these symptoms.[22] They start with muscle tightness, then a painful burning if exercise continues.[22] A few minutes after exercise stops, the compartment pressure will drop,[16] relieving the pain.[21] Symptoms occur after a certain level of exercise.[11] This threshold can range anywhere from 30 seconds of running to 2–3 miles of running.[23] CECS most often occurs in the lower leg.[11] The anterior compartment is most affected.[11] Foot drop is a common symptom.[21][22]

Causes

Acute

Acute compartment syndrome (ACS) is a medical emergency.[5] It can develop after traumatic injuries, like car accidents, gunshot wounds, fractures, or intense sports.[24] Examples include a severe crush injury or an open or closed fracture of an extremity.[24] Rarely, ACS can develop after a minor injury or another medical issue.[25] It can also affect the thigh, buttock, hand, abdomen, and foot.[17][12] The most common cause of acute compartment syndrome is a fractured bone, usually the tibia.[12][26] Leg compartment syndrome occurs in 1–10% of tibial fractures.[6] It is strongly linked to tibial diaphysis fractures and other tibial injuries.[27] Direct injury to blood vessels can reduce blood flow to soft tissues, causing compartment syndrome.[24] Compartment syndrome can also be caused by:

- intravenous drug injection

- casts

- prolonged limb compression

- crush injuries

- anabolic steroid use

- vigorous exercise

- eschar from burns[28][29]

Patients on anticoagulant therapy, or those with blood disorders such as hemophilia or leukemia are at higher risk of developing compartment syndrome.[30][31][17]

Abdominal compartment syndrome occurs when the intra-abdominal pressure exceeds 20 mmHg and abdominal perfusion pressure is less than 60 mmHg.[32] There are many causes, which can be broadly grouped into three mechanisms: primary (internal bleeding and swelling); secondary (vigorous fluid replacement as an unintended complication of resuscitative medical treatment, leading to the acute formation of ascites and a rise in intra-abdominal pressure); and recurrent (compartment syndrome that has returned after the initial treatment of secondary compartment syndrome).[32][33]

Compartment syndrome after snake bite is rare.[34] Its incidence varies from 0.2% to 1.36% as recorded in case reports.[35] Compartment syndrome after a snake bite is more common in children.[34] Increased white blood cell count of more than 1,650/μL and aspartate transaminase (AST) level of more than 33.5 U/L are associated with developing compartment syndrome.[35] Otherwise, those bitten by venomous snakes should be observed for 48 hours to exclude the possibility of compartment syndrome.[35]

Acute compartment syndrome due to severe/uncontrolled hypothyroidism is rare.[36]

Chronic

Chronic compartment syndrome (CCS) is when repeated use of the muscles causes compartment syndrome.[37][38] This is usually not an emergency, but loss of circulation can damage nearby nerves and muscles.[38] The damage may be temporary or permanent.[37][38]

A subset is chronic exertional compartment syndrome (CECS), often called exercise-induced compartment syndrome (EICS).[39] CECS is often a diagnosis of exclusion.[40] CECS of the leg is caused by exercise.[41] This condition occurs commonly in the lower leg and various other locations within the body, such as the foot or forearm.[11] CECS can be seen in athletes who train rigorously in activities that involve constant repetitive actions or motions.[39]

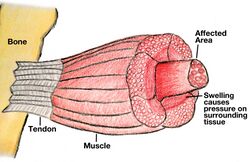

Pathophysiology

ACS is defined as a critical pressure increase within a confined compartmental space causing a decline in the perfusion pressure to the tissue within that compartment.[5] A normal human body needs a pressure gradient for blood flow.[42] It must go from the higher-pressure arterial system to the lower-pressure venous system.[5][42] This causes blood to back up.[5] Excess fluid leaks from the capillaries into the spaces between the soft tissue's cells.[43] This swells the extracellular space and raises the pressure in the compartment.[5][44] The swelling of the soft tissues around the blood vessels compresses the blood and lymphatic vessels.[44][42] This causes more fluid to enter the extracellular spaces, leading to further compression.[5] The pressure keeps rising due to the non-compliant fascia in the compartment.[5] This cycle can cause tissue ischemia, a lack of oxygen, and necrosis, or tissue death.[6][5][42] Paresthesia, or tingling, can start as early as 30 minutes after tissue ischemia begins.[45] Permanent damage can occur 12 hours after the injury starts.[45]

The reduced blood supply can trigger inflammation.[6] This can cause the soft tissues to swell.[5] Reperfusion therapy can worsen this inflammation.[5] The fascia that defines the limbs' compartments does not stretch.[6] Even a small bleed or muscle swelling can greatly raise the pressure.[8][6][5]

The pathophysiology of CECS is not entirely understood. In CECS, pressure in an anatomical compartment increases due to a 20% increase in muscle volume.[41] This builds pressure in the tissues and muscles, causing ischemia.[41] Increased muscle weight reduces the compartment volume of the surrounding fascial borders, raising compartment pressure.[39] An increase in the pressure of the tissue can force fluid to leak into the interstitial space (extracellular fluid), leading to a disruption of the micro-circulation of the leg.[39]

Diagnosis

Compartment syndrome is a clinical diagnosis.[12] It comes from a provider's exam and the patient's history.[5][12] Diagnosis may also require measuring intracompartmental pressure.[5][6] Using both methods increases the accuracy of diagnosing compartment syndrome.[7] A transducer connected to a catheter is inserted 5 cm into the zone of injury to measure the intracompartmental pressure.[9][5] Normal pressure is 10 mmHg.[5] Anything greater can compromise circulation, and 30 mmHg has been commonly cited as the upper threshold before circulation is lost.[5]

Noninvasive methods, like near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), show promise in controlled settings.[46] NIRS uses sensors on the skin.[46] However, with limited data, the gold standard for diagnosis is the clinical presentation and intracompartmental pressure.[46]

Chronic exertional compartment syndrome is often diagnosed by ruling out other conditions.[11][22] The key sign is that there are no symptoms when at rest.[1][47] The best test is to measure intracompartmental pressures after running, when symptoms return.[47][1] Tests like X-rays, CT scans, and MRIs help rule out other problems.[11] But they don't confirm compartment syndrome.[11] However, MRI is effective for diagnosing chronic exertional compartment syndrome.[48]

Treatment

Acute

If external compression, such as a cast or tourniquet, has caused increased pressure, it is removed and the limb placed at heart level. Otherwise, fasciotomy, a cut into the fascia beneath the skin, immediately decreases pressure and is generally the only effective treatment.[17] Although closing a fasciotomy wound quickly reduces complications, this is not typically achievable as compartment syndrome may recur. Before the wound is closed, it may be covered with moist dressings or, in some cases, treated with negative-pressure wound therapy, which can additionally be used for closure. Closure is often achieved using the so-called shoelace technique, where staples are inserted into the skin which are used to pull the sides of the wound together with a thread. A skin graft may be needed to close the wound.[49] Fasciotomy is often not necessary when compartment syndrome is caused by snake bites, where pressure may instead be relieved with antivenom.[50]

Chronic

Chronic exertional compartment syndrome can be treated by reducing or stopping exercise-related activities, massage, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication, and physiotherapy.[1] If symptoms persist after basic treatment, compartment syndrome may be treated with a fasciotomy.[51][47]

Prognosis

Researchers have reported a mortality rate of 47% for acute compartment syndrome of the thigh.[52] A study showed the fasciotomy rate for acute compartment syndrome ranges from 2% to 24%.[17] The key factor in acute compartment syndrome is the time to diagnosis and fasciotomy.[25] A missed or late diagnosis may require limb amputation to survive.[53][54] After a fasciotomy, some symptoms may be permanent.[54] It depends on which compartment was affected, the time until surgery, and muscle necrosis.[25][24] Muscle necrosis can happen fast, sometimes within just 3 hours after an injury.[54] A fasciotomy in the leg's lateral compartment might cause symptoms affecting nearby nerves and muscles.[10] These may include foot drop, numbness along leg, numbness of big toe, pain, and loss of foot eversion.[10]

Complications

If pressure is not relieved, tissues may die (necrosis) in the affected compartment.[9][25] Blood will be unable to enter the smallest vessels.[5][44] Capillary perfusion pressure will fall.[5][44] This, in turn, leads to a gradual lack of oxygen in the tissues that depend on this blood supply.[55] Without enough oxygen, the tissue will die.[54] On a large scale, this can cause Volkmann's contracture in the affected limbs.[56][57][58] It is permanent and irreversible.[56] Other complications include neurological deficits, gangrene, and chronic regional pain syndrome.[59] Rhabdomyolysis and kidney failure are also possible.[60] Some case series report rhabdomyolysis in 23% of patients with ACS.[17]

Epidemiology

In a case series of 164 people with acute compartment syndrome, 69% had an associated fracture.[61] The article's authors found that the yearly rate of acute compartment syndrome is 1 to 7.3 cases per 100,000 people.[61] It varies greatly by age and gender in trauma.[12] Men are ten times more likely than women to get ACS.[6] The mean age for ACS is 30 in men and 44 in women.[17] People under 35 may get ACS more often.[6][5] This is likely because they have more muscle mass.[5][6] The anterior compartment of the leg is where ACS usually happens.[6][62]

In children

The pathophysiology of acute compartment syndrome in children is the same as adults.[63] However, cases are complicated by challenges in examination and communication with pediatric patients.[63] Children may not be able to effectively report their pain symptoms.[64] In addition, it can take longer to develop high pressures in pediatric compartments.[64][65] Besides the "5 Ps," the "3 As" can diagnose compartment syndrome in children: increasing anxiety, agitation, and analgesic needs.[66] Normal compartment pressures in children are typically higher than adults.[67] The most common cause of compartment syndrome in children is traumatic injury.[68] In children <10 years of age, the cause is usually vascular injury or infection.[69] In children >14 years of age, the cause is usually due to trauma or surgical positioning.[69] Treatment for compartment syndrome in children is the same as adults.[63]

See also

- Abdominal compartment syndrome

- Escharotomy

- Ischemia-reperfusion injury of the appendicular musculoskeletal system

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 "Chronic exertional compartment syndrome: current management strategies". Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine 10: 71–79. May 2019. doi:10.2147/oajsm.s168368. PMID 31213933.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Challenging Cases in Dermatology. Springer Science & Business Media. 2013. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-4471-4249-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=EF3ONrFuF2kC&pg=PA145.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2018 E-Book: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2017. p. 317. ISBN 978-0-323-52957-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=wGclDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA317.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Acute Compartment Syndrome". The Orthopedic Clinics of North America 47 (3): 517–525. July 2016. doi:10.1016/j.ocl.2016.02.001. PMID 27241376.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 5.20 5.21 5.22 5.23 5.24 5.25 5.26 5.27 5.28 5.29 5.30 5.31 5.32 5.33 "The pathophysiology, diagnosis and current management of acute compartment syndrome". The Open Orthopaedics Journal 8: 185–193. 2014. doi:10.2174/1874325001408010185. PMID 25067973.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 6.17 6.18 6.19 6.20 "Acute Compartment Syndrome". StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing). 2020. PMID 28846257. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448124/. Retrieved 2020-01-15.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 The Trauma Manual: Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2008. p. 349. ISBN 978-0-7817-6275-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=JnTMQOMcYZwC&pg=PA349.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 "Compartment Syndrome – National Library of Medicine". https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMHT0024266/.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 "The diagnosis of acute compartment syndrome: a review". European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery 40 (5): 521–528. October 2014. doi:10.1007/s00068-014-0414-7. PMID 26814506.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "Lower extremity compartment syndrome". Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open 2 (1). 2017-09-14. doi:10.1136/tsaco-2017-000094. PMID 29766095.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 "A review of chronic exertional compartment syndrome in the lower leg". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 32 (3 Suppl): S4-10. March 2000. doi:10.1249/00005768-200003001-00002. PMID 10730989.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 "Compartment syndrome: diagnosis, management, and unique concerns in the twenty-first century". HSS Journal 10 (2): 143–152. July 2014. doi:10.1007/s11420-014-9386-8. PMID 25050098.

- ↑ "Paediatric well leg compartment syndrome following femoral fracture fixation: A case report". Journal of Orthopaedic Reports 2 (4). 2023-12-01. doi:10.1016/j.jorep.2023.100203. ISSN 2773-157X.

- ↑ "Acute compartment syndrome". Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal 5 (1): 18–22. 2015-03-27. PMID 25878982.

- ↑ "Compartment syndrome of the lower leg and foot". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 468 (4): 940–950. April 2010. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-0891-x. PMID 19472025.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Exertional Compartment Syndrome". StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing). 2020. PMID 31335004. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544284/. Retrieved 2020-01-22.

- ↑ 17.00 17.01 17.02 17.03 17.04 17.05 17.06 17.07 17.08 17.09 "Acute compartment syndrome". Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal 5 (1): 18–22. 2015. PMID 25878982.

- ↑ "A systematic review of the effect of regional anesthesia on diagnosis and management of acute compartment syndrome in long bone fractures". European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery 46 (6): 1281–1290. December 2020. doi:10.1007/s00068-020-01320-5. PMID 32072224.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Diagnosis Accuracy for Compartment Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma 37 (8): e319–e325. August 2023. doi:10.1097/BOT.0000000000002610. PMID 37053115.

- ↑ "Chronic exertional compartment syndrome of the leg in the military". Clinics in Sports Medicine 33 (4): 693–705. October 2014. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2014.06.010. PMID 25280617.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 "Chronic exertional compartment syndrome: diagnosis and management". Bulletin 62 (3–4): 77–84. 2005. PMID 16022217. http://hjdbulletin.org/files/archive/pdfs/639.pdf.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 "Chronic Exercise-Induced Compartment Syndrome of the Leg". Harvard Orthopaedic Journal 1 (7). http://www.orthojournalhms.org/volume1/html/articles07.html. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ↑ "Exertional compartment syndrome: review of the literature and proposed rehabilitation guidelines following surgical release". International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy 6 (2): 126–141. June 2011. PMID 21713230.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 "Factors Associated with Development of Traumatic Acute Compartment Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". The Archives of Bone and Joint Surgery 9 (3): 263–271. May 2021. doi:10.22038/abjs.2020.46684.2284. PMID 34239953.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 "Acute compartment syndrome: obtaining diagnosis, providing treatment, and minimizing medicolegal risk". Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine 5 (3): 206–213. September 2012. doi:10.1007/s12178-012-9126-y. PMID 22644598.

- ↑ "Acute Compartment Syndrome: Do guidelines for diagnosis and management make a difference?". Injury 49 (9): 1699–1702. September 2018. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2018.04.020. PMID 29699733.

- ↑ "Aetiology of trauma-related acute compartment syndrome of the leg: A systematic review". Injury 50 Suppl 2 (Suppl 2): S57–S64. July 2019. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2019.01.047. PMID 30772051.

- ↑ "Diagnosis and management of extremity compartment syndromes: an orthopaedic perspective". The American Surgeon 73 (12): 1199–1209. December 2007. doi:10.1177/000313480707301201. PMID 18186372.

- ↑ "Compartment syndrome: wound care considerations". Advances in Skin & Wound Care 20 (10): 559–65; quiz 566–7. October 2007. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000294758.82178.45. PMID 17906430.

- ↑ "Acute compartment syndrome as the initial manifestation of chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia: a case report and review of the literature". Journal of Medical Case Reports 10 (1): 201. July 2016. doi:10.1186/s13256-016-0985-5. PMID 27443161.

- ↑ "Compartment syndrome in patients with haemophilia". Journal of Orthopaedics 12 (4): 237–241. December 2015. doi:10.1016/j.jor.2015.05.007. PMID 26566325.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 "Abdominal compartment syndrome". Critical Care Medicine 36 (4 Suppl): S212–S215. April 2008. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e318168e333. PMID 18382196.

- ↑ "Incidence of Intra-Abdominal Hypertension and Abdominal Compartment Syndrome: A Systematic Review". Journal of Intensive Care Medicine 36 (2): 197–202. February 2021. doi:10.1177/0885066619892225. PMID 31808368.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 "Compartment Syndrome Following Snake Bite". Oman Medical Journal 30 (2): e082. March 2015. doi:10.5001/omj.2015.32. PMID 30834067.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 "Predictors of the development of post-snakebite compartment syndrome". Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine 23: 97. November 2015. doi:10.1186/s13049-015-0179-y. PMID 26561300.

- ↑ "Acute compartment syndrome caused by uncontrolled hypothyroidism". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 35 (6): 937.e5–937.e6. June 2017. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2016.12.054. PMID 28043728.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 "Cycling injuries of the lower extremity". The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 15 (12): 748–756. December 2007. doi:10.5435/00124635-200712000-00008. PMID 18063715.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 "The exertional compartment syndrome: A review of the literature". Ortopedia, Traumatologia, Rehabilitacja 4 (5): 626–631. October 2002. PMID 17992173.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 "Exercise induced compartment syndrome in a professional footballer". British Journal of Sports Medicine 38 (2): 227–229. April 2004. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2003.004630. PMID 15039267.

- ↑ "Chronic Exertional Compartment Syndrome in Athletes". The Journal of Hand Surgery 42 (11): 917–923. November 2017. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2017.09.009. PMID 29101975.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 "Lower leg pain. Diagnosis and treatment of compartment syndromes and other pain syndromes of the leg". Sports Medicine 27 (3): 193–204. March 1999. doi:10.2165/00007256-199927030-00005. PMID 10222542.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 "Aetiology of trauma-related acute compartment syndrome of the leg: A systematic review". Injury 50 Suppl 2: S57–S64. July 2019. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2019.01.047. PMID 30772051.

- ↑ "Physiology, Edema", StatPearls (Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing), 2025, PMID 30725750, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537065/, retrieved 2025-01-23

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 "The pathophysiology, diagnosis and current management of acute compartment syndrome". The Open Orthopaedics Journal 8 (1): 185–193. 2014-06-27. doi:10.2174/1874325001408010185. PMID 25067973.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 "Series introduction: tissue ischemia: pathophysiology and therapeutics". The Journal of Clinical Investigation 106 (5): 613–614. September 2000. doi:10.1172/JCI10913. PMID 10974010.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 "Non-invasive Diagnostics for Extremity Compartment Syndrome following Traumatic Injury: A State of the Art Review". The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 87 (1S Suppl 1): S59–S66. 2019-04-01. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000002284. PMID 31246908.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 "Characteristics of patients with chronic exertional compartment syndrome". Foot & Ankle International 34 (10): 1349–1354. October 2013. doi:10.1177/1071100713490919. PMID 23669162.

- ↑ "Chronic exertional compartment syndrome" (in en), Radiopaedia.org, 2013-03-17, doi:10.53347/rid-22182, http://radiopaedia.org/articles/22182, retrieved 2025-01-23

- ↑ "Fasciotomy Wound Management" (in en), Compartment Syndrome (Cham: Springer International Publishing): pp. 83–95, 2019, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-22331-1_9, ISBN 978-3-030-22330-4, PMID 32091732

- ↑ "Algorithmic approach to the prevention of unnecessary fasciotomy in extremity snake bite". Injury 47 (12): 2822–2827. December 2016. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2016.10.023. PMID 27810154.

- ↑ Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society. "Crush Injury, Compartment syndrome, and other Acute Traumatic Ischemias". http://www.uhms.org/ResourceLibrary/Indications/CrushInjury/tabid/274/Default.aspx.

- ↑ "Compartment syndrome of the thigh: a systematic review" (in English). Injury 41 (2): 133–136. February 2010. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2009.03.016. PMID 19555950.

- ↑ "Managing missed lower extremity compartment syndrome in the physiologically stable patient: A systematic review and lessons from a Level I trauma center". The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 81 (2): 380–387. August 2016. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000001107. PMID 27192464.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 54.3 "Evaluation and Management of Acute Compartment Syndrome in the Emergency Department". The Journal of Emergency Medicine 56 (4): 386–397. April 2019. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.12.021. PMID 30685220.

- ↑ "Acute compartment syndrome of the limb". Trauma 8 (4): 261–266. October 2006. doi:10.1177/1460408606076963.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Green's operative hand surgery. Volume 2 (Seventh ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. 2017. ISBN 978-1-4557-7427-2.

- ↑ "Peripheral nerve-conduction block by high muscle-compartment pressure" (in en-US). The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume 61 (2): 192–200. March 1979. doi:10.2106/00004623-197961020-00006. PMID 217879.

- ↑ "Lower extremity compartment syndrome". Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open 2 (1). 2017-10-01. doi:10.1136/tsaco-2017-000094. PMID 29766095.

- ↑ "Compartment syndrome of the forearm: a systematic review". The Journal of Hand Surgery 36 (3): 535–543. March 2011. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.12.007. PMID 21371630.

- ↑ "Acute Exertional Compartment Syndrome with Rhabdomyolysis: Case Report and Review of Literature". The American Journal of Case Reports 19: 145–149. February 2018. doi:10.12659/AJCR.907304. PMID 29415981.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 "Acute compartment syndrome. Who is at risk?". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume 82 (2): 200–203. March 2000. doi:10.1302/0301-620x.82b2.0820200. PMID 10755426.

- ↑ "Tibial Anterior Compartment Syndrome". StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing). 2020. PMID 30085512. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK518970/. Retrieved 2020-01-31.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 Hak, David J. (2019), Mauffrey, Cyril; Hak, David J.; Martin III, Murphy P., eds., "Acute Compartment Syndrome in Children" (in en), Compartment Syndrome (Cham: Springer International Publishing): pp. 125–132, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-22331-1_13, ISBN 978-3-030-22330-4, PMID 32091730, http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-22331-1_13, retrieved 2025-01-28

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Flynn, John M; Bashyal, Ravi K; Yeger-McKeever, Meira; Garner, Matthew R; Launay, Franck; Sponseller, Paul D (May 2011). "Acute Traumatic Compartment Syndrome of the Leg in Children: Diagnosis and Outcome" (in en). The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery-American Volume 93 (10): 937–941. doi:10.2106/JBJS.J.00285. ISSN 0021-9355. PMID 21593369. http://journals.lww.com/00004623-201105180-00006.

- ↑ Livingston, Kristin; Glotzbecker, Michael; Miller, Patricia E.; Hresko, Michael T.; Hedequist, Daniel; Shore, Benjamin J. (October 2016). "Pediatric Nonfracture Acute Compartment Syndrome: A Review of 39 Cases" (in en). Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics 36 (7): 685–690. doi:10.1097/BPO.0000000000000526. ISSN 0271-6798. PMID 26019026. https://journals.lww.com/01241398-201610000-00006.

- ↑ Noonan, Kenneth; McCarthy, James (September 2011). "Compartment Syndromes in the Pediatric Patient". Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics 31: ii. doi:10.1097/01.bpo.0000405143.30083.85. ISSN 0271-6798.

- ↑ Staudt, J. M.; Smeulders, M. J. C.; van der Horst, C. M. A. M. (February 2008). "Normal compartment pressures of the lower leg in children" (in en). The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume 90-B (2): 215–219. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.90B2.19678. ISSN 0301-620X. PMID 18256091. https://online.boneandjoint.org.uk/doi/10.1302/0301-620X.90B2.19678.

- ↑ Mashru, Rakesh P.; Herman, Martin J.; Pizzutillo, Peter D. (September 2005). "Tibial Shaft Fractures in Children and Adolescents" (in en). Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 13 (5): 345–352. doi:10.5435/00124635-200509000-00008. ISSN 1067-151X. PMID 16148360. http://journals.lww.com/00124635-200509000-00008.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Shore, Benjamin J.; Glotzbecker, Michael P.; Zurakowski, David; Gelbard, Estee; Hedequist, Daniel J.; Matheney, Travis H. (November 2013). "Acute Compartment Syndrome in Children and Teenagers With Tibial Shaft Fractures: Incidence and Multivariable Risk Factors" (in en). Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma 27 (11): 616–621. doi:10.1097/BOT.0b013e31828f949c. ISSN 0890-5339. PMID 23481923. https://journals.lww.com/00005131-201311000-00006.

External links

- Compartment Syndrome of the Forearm – Orthopaedia.com

- Chronic Exertional Compartment Syndrome detailed at MayoClinic.com

- Compartment_syndrome at the Duke University Health System's Orthopedics program

- 05-062a. at Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy Home Edition

- Compartment syndrome

- American Association of Orthopaedic Surgeons Compartment Syndrome

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|

KSF

KSF