Epidemics Act

Topic: Medicine

From HandWiki - Reading time: 13 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 13 min

| Epidemics Act (EpidA) | |

|---|---|

| Federal Assembly of Switzerland | |

Long title

| |

| Territorial extent | Switzerland |

| Enacted by | Federal Assembly of Switzerland |

| Enacted | 28 September 2012 |

| Commenced | 1 January 2016 |

| Repeals | |

| Epidemics Act (1970) | |

| Status: Current legislation | |

Epidemics Act (EpidA),[lower-alpha 1] also known as Federal Act on the Control of Communicable Human Diseases, is a Swiss federal act designed to protect people from infections and to prevent and control the outbreak and spread of communicable diseases. The current version of the Epidemics Act is the result of the revision of September 28, 2012. The revision was necessary because the environment in which communicable diseases occur and pose a threat to public health has changed, and the law needed to be adapted accordingly.

An optional referendum against this revision was initiated by the EDU, the Citizens for Citizens Association (Verein Bürger für Bürger) and the Committee for True Democracy (Wahre Demokratie), and the 50,000 signature quorum was reached within 100 days. As a result, a referendum was held on September 22, 2013, in which the complete revision was approved by 60% of the population.

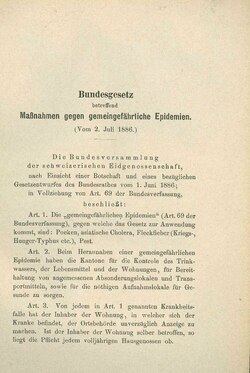

Development

The Federal Act on the Control of Communicable Human Diseases of September 28, 2012, currently in force, is a complete revision of the Federal Act of December 18, 1970. In turn, this was based on the Federal Act on Measures Against Publicly Dangerous Epidemics (Bundesgesetz betreffend Massnahmen gegen gemeingefährliche Epidemien) of July 2, 1886. The Epidemics Act of 1886 solely addressed public health epidemics, namely smallpox, cholera, typhus and the plague. Any other diseases were a cantonal matter. The typhus epidemic of 1963 in Zermatt, with about 400 cases and several deaths, led to a complete revision of the Epidemics Act of 1886. Previous outbreaks of diseases such as tuberculosis had also led to changes in the Federal Constitution (FC). Between the complete revision of December 18, 1970, and the update of September 28, 2012, there were various minor revisions, most recently in 2006. Almost all of these revisions have significantly increased the scope of the Confederation's powers.[1]

Purpose

The revised Epidemics Act aims to swiftly and efficiently coordinate all infrastructures that can aid in the monitoring, prevention, and control of human communicable diseases. The Confederation can promptly declare three levels of severity under the EpidA: normal, special, and extraordinary situations.

During a "normal situation", the cantons are responsible for enforcing the Epidemics Act and the Epidemics Ordinance (Epidemienverordnung or EpV). The Confederation has limited competencies, which include providing information and recommendations, controlling entry and exit, and coordinating with cantons upon request.

In a "special situation",[2] the Federal Council (Bundesrat) may order individual quarantines, restrict capacity at events or even cancel them; it is authorized to close schools; it may require physicians and other health professionals to cooperate to control the then-emerging disease; and it may declare vaccinations mandatory. Regulations can take the form of a specific injunction, such as banning a particular event, or an ordinance, such as prohibiting events throughout Switzerland. The "special situation" is defined as an epidemiological emergency and can be compared to a moderate influenza pandemic, the SARS pandemic, and H1N1. The FDHA coordinates federal measures during a "special situation". The "special situation" occurs when "the ordinary law enforcement agencies are unable to prevent and control the outbreak and spread of communicable diseases".[3] Additionally, one of the following risks must also be present:

- A high risk of infection and of spread.[3]

- A special risk to public health.[3]

- Serious consequences for the economy or for other areas of life.[3]

In an "extraordinary situation",[4] the Federal Council may, on the basis of Art. 185 (3) of the FC, issue an emergency decree without any basis in a federal act passed by parliament, and subject to an optional referendum by the people. Since the Federal Council is already constitutionally empowered to issue these ordinances, Art. 7 of the EpidA is of a declaratory nature. Due to the unpredictability of an acute, serious threat to public health, no specific measures are provided for the "extraordinary situation". In the event of an outbreak, the constitutional emergency law allows the Federal Council to order appropriate measures. According to Art. 7d of the Government and Administration Organisation Act (GAOA), these ordinances shall become invalid if the Federal Council does not submit to Parliament (within six months) a bill for a federal act or a parliamentary emergency ordinance to replace those of the Federal Council. An "extraordinary situation" requires a national threat that endangers Switzerland's external or internal security. Only worst-case pandemics would qualify, such as the Spanish flu or the COVID-19 pandemic.[5]

Content

Detection and monitoring

Art. 11 of the EpidA gives the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) responsibility for setting up and operating systems for the early detection and monitoring of potential hazards. This is done in close cooperation between the FOPH and the cantons, but also with the Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office (FSVO) or the Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN). This close cooperation between the FOPH, other federal agencies and the cantons is of great importance. The cantons contribute their proximity to epidemiological events and health-related incidents and their responsibility for enforcement, while the FOPH ensures uniform reporting and evaluation criteria, professional epidemiological data processing and international networking. The involvement of other federal agencies enables a uniform evaluation of the situation and thus uniform enforcement.

The central instrument for this is the reporting obligation under Art. 12 of the EpidA. It stipulates that the medical profession, hospitals, rehabilitation centers, nursing homes, outpatient clinics, organizations or telephone medical hotlines and pharmacies must report communicable diseases to the FOPH or the competent cantonal authority. Diseases associated with an epidemic risk or severe course are monitored. This includes events that are novel or unexpected or for which monitoring is internationally agreed. The reporting obligation is specified in Art. 12 of the EpidA. The diagnosing physicians must report observations of communicable diseases to the cantonal medical services, which in turn forward these reports to the FOPH. In principle, the reports are first sent to the authority responsible for emergency measures. In certain cases, particularly when emergency measures involve more than one canton and international notification is required, reports should also be sent directly to the FOPH. In addition, the Federal Council may order reports on prevention and control measures and their effects, as well as the sending of samples and test results to laboratories designated by the competent authorities.

Prevention

Vaccines

The FOPH and the Federal Commission for Vaccination (FCV) regulate vaccination strategies and objectives. To implement them, both bodies issue specific vaccination recommendations. Art. 20(2) of the EpidA states:

"Doctors and other healthcare specialists shall assist in implementing the national vaccination plan as part of their activities."

According to Art. 22 of the EpidA:

"The cantons may declare vaccinations to be mandatory for population groups at high risk, persons who are particularly exposed to infection and persons that carry out certain activities, provided there is a significant risk."

In the case of "special" and "exceptional" situations, the Federal Council may also order compulsory vaccination (Swiss: Impfobligatorium). Mandatory vaccination can therefore only be imposed on vulnerable groups and not generally on the entire population. Moreover, this measure is reserved for situations in which all other means have been exhausted. This is because mandatory vaccination interferes with personal freedom.[6] According to Art. 36 of the Federal Constitution (FC), such restrictions on fundamental rights is only permissible if:

- They are based on a sound legal foundation.

- They are justified in the public interest (in the event of highly contagious diseases with potentially serious outcomes).

- They are proportionate.

Mandatory vaccination of specific populations may be necessary in the event of a severe, swiftly spreading, and sometimes lethal infectious illness.

Compensation for any pain and suffering resulting from a vaccine adverse event is covered by Art. 64 ff. of the EpidA.

Biosafety

The Epidemics Act requires due care (Sorgfalt) to be exercised by anyone handling pathogens or their toxic products. It specifies that all measures must be taken to ensure that no harm comes to humans as a result of this activity.[7] This due care includes the handling of genetic material or microorganisms that could cause disease as a result of genetic modification. Art. 28 of the EpidA states:

"Anyone who places pathogens on the market must inform purchasers about the properties and hazards relevant to health and about the necessary precautionary and protective measures."

The Federal Council is also authorized to restrict or ban the handling of certain pathogens. The WHO Action Plan for the eradication of poliomyelitis may also require the destruction of polio infectious materials or the prohibition and/or restriction of the handling of polioviruses in closed systems in the long term. Additionally, the Federal Council's competence in the field of biological weapons is within the framework of Switzerland's obligations under international law.[lower-alpha 2]

Countermeasures

Most measures to safeguard public health have an impact on constitutionally guaranteed freedoms. Consequently, the competent authorities should assume responsibility. Decisions must also be made in cases where adequate scientific assessment is complicated. Since not all hazards can be conclusively defined, the competent authorities have a wide margin of discretion in deciding how to take action. In compliance with the principle of proportionality, these actions are lawful only if all less restrictive actions have been explored.

Based on the varying intensities of these measures, the Federal Council outlines a series of stages as required by law. The least severe measure is medical monitoring.[8] The ban on practicing a profession or activity would have a stronger intrusive effect.[9] Seclusion in a hospital or another appropriate institution is the most restrictive measure,[10] along with an order for medical treatment.[11] The law distinguishes between isolation and quarantine. Isolation refers to the confinement of individuals who are sick and infected, while quarantine refers to the confinement of individuals who are suspected of being sick or infected. The aim of both measures is to stop the transmission of infection. Both measures must be ordered beforehand at the individual's place of residence. Transfer to an alternate facility is only allowed if staying at home is inadequate or ineffective in stopping the continued spread of the disease.

The Epidemics Act provides numerous mechanisms to cantonal authorities to prevent the transmission of communicable diseases. For example, Art. 40 stipulates that events may be either banned or restricted; schools and other public institutions may be closed; and entry to and exit from certain buildings and areas, as well as certain activities in certain places, may be prohibited. According to Art. 41(2), the FOPH is authorized to require individuals entering or leaving Switzerland:

- Provide their identity, itinerary and contact information.

- Provide a vaccination or prophylaxis certificate.

- Provide information on their health status.

- Provide proof of a medical examination.

- To undergo a medical examination.

To prevent the spread of a disease, individuals may be denied permission to leave the country by the FOPH. However, this measure should only be used as a last resort.

Organization and procedures

The Epidemics Act establishes two bodies: the Emergency Response Body and the Coordination Body.

The Emergency Response Body exists only temporarily and can be called into action in special and extraordinary situations.[12] If this occurs, any special task force[13] set up in the course of the epidemiological emergency is disbanded and transferred to the Emergency Response Body. The Emergency Response Body is responsible for advising the Federal Council and coordinating measures.

Since the complete revision on September 28, 2012, a Coordination Body (Koordinationsorgan or KOr) has been established with legal support in Art. 54 of the EpidA. Its role is to coordinate technical collaboration between the Confederation and the cantons, but it lacks decision-making or enforcement capabilities, as these are the responsibility of the Confederation and the cantons. The Coordination Body may establish sub-bodies as necessary, one of which pertains to zoonoses. These sub-bodies shall be staffed mainly by members of the FOPH and cantonal doctors. Although the Federal Council oversees the Coordination Body, it does not constitute an extraparliamentary commission as defined in Art. 57a of the GAOA.

The law establishes the Federal Commission for Vaccination (FCV)[14] and the Swiss Expert Committee for Biosafety (SECB).[15] The FCV is responsible for advising the Federal Council on legislation and the federal and cantonal authorities on enforcement. The SECB offers guidance to authorities on safeguarding human and environmental well-being in the realm of biotechnology and gene technology.

Implementation

Enforcing the Epidemics Act falls under the jurisdiction of the cantons, unless the Confederation assumes responsibility.[16] This is in accordance with the Federal Constitution, which states in Art. 118 (2) that the Confederation is operationally active only in specific health protection areas. Nevertheless, the Confederation has exclusive responsibility for legislation on communicable diseases and ensures that federal law is enforced by the cantons.[17]

According to Art. 77(2) of the EpidA, the Confederation coordinates enforcement measures among the cantons in cases where there is a need for uniformity. Therefore, it can direct the cantons to implement certain measures or issue regulations to ensure uniform enforcement if a risk to public health is identified.[18]

Complete revision of September 28, 2012

Initial situation

The Federal Council concluded in its official statement that the current Epidemics Act was no longer adequate. Since the implementation of the Epidemics Act in 1970, significant changes took place that necessitated a complete revision, both from a legal and technical point of view. The legal situation, in the Federal Council's view, was too ambiguous to sufficiently prepare for a disease's outbreak and spread. Reliance on emergency articles was widespread,[19][20] albeit their scope remained ambiguously defined, as evidenced by the SARS pandemic. In addition, the current law was limited to sanitary measures and largely excluded preventive measures. Ultimately, what was missing was a "purpose article," which would make it clear what public interests were being served by the legislation. The lack of a purpose article hindered the establishment of a basis for legal action.

Procedure

The need for a revision of the Epidemics Act was undisputed during the negotiations. Only the vaccination obligation proposed by the Federal Council was controversial in the National Council. Opponents of compulsory vaccination oppose it due to infringement on personal freedom. Additionally, the effectiveness and side effects of new vaccines often require years to be proven. Supporters, however, argued that public health must be prioritized over individual freedom in emergency situations. Moreover, it was proposed as a vaccination policy, meaning no individual was compelled to receive vaccination against their will; nevertheless, those who refused to comply may face consequences under labor law. A proposal to weaken the vaccination mandate, presented by opponents, was defeated in votes of 94 to 69 and 105 to 51. In contrast, a proposal put forward by the SP and SVP was approved with a vote of 103 to 62. According to this proposal, the cantons would no longer have the authority to order vaccinations. They would solely be able to propose and recommend them.

The Council of States approved, by a margin of 7 votes to 11, the competence of the cantons to make vaccinations compulsory for certain groups of people under certain circumstances. Since this was contrary to the National Council's decision, a "resolution of differences" (Differenzbereinigung) took place in which the National Council bowed to the Council of States' decision and accepted (by 88 votes to 78) that cantons could make vaccinations compulsory.

The new federal law gained approval in the National Council by a vote of 149 to 14 with 25 abstentions, and in the Council of States by a vote of 40 to 2 with 3 abstentions.[21]

Amendments to the previous Act

In comparison with the Act of 1970, some aspects have changed as a result of the complete

- A new tiered model has been introduced to improve the distribution of roles between the Confederation and the cantons during crisis situations. This model is composed of three levels: normal, special, and extraordinary situations.

- A mandatory vaccination can no longer be imposed on the general public, but only on designated individuals. The Federal Council can now exercise the authority to mandate vaccination during special or extraordinary situations, with the same criteria applying as for the cantons.

- Explicit legal provisions have been established to enhance crisis prevention and management.

- The Confederation's leadership role was expanded by the new Act. For instance, it is accountable for establishing the nation's objectives and strategies in combating communicable diseases, as well as overseeing the enforcement of the Epidemics Act.

- The Coordinating Body was recently established.[22]

Optional referendum

On September 28, 2012, the Federal Assembly passed a resolution to adopt the revised Act. The Federal Chancellery published the decision in the Federal Gazette, and the referendum period began (100 days for 50,000 signatures[23]). On January 17, 2013, the signatures were submitted by the Referendum Committee.[24] The referendum was announced by the Federal Chancellery on February 19, 2013, with 77,360 valid signatures.[25] The Act was approved with a 60.00% majority in a referendum held on September 22, 2013.[26] It became effective on January 1, 2016.

Referendum

Stances

- In favor: BDP, CSP, CVP, EVP, FDP, GLP, GPS, MCG, SD, SP

- Against: EDU, SVP, FPS, KVP[27]

Results

| Canton | Yes (%) | No (%) | Participation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zurich | 60,5 % | 30,5 % | 49,28% |

| Bern | 54,9 % | 45,1 % | 44,77 % |

| Lucerne | 59,5 % | 40,5 % | 47,56 % |

| Uri | 49,5 % | 50,5 % | 44,85 % |

| Schwyz | 45,5 % | 54,5 % | 49,67 % |

| Obwalden | 51,4 % | 48,6 % | 49,71 % |

| Nildwalden | 56,1 % | 43,9 % | 50,00 % |

| Glarus | 51,3 % | 48,7 % | 38,27 % |

| Zug | 57,4 % | 42,6 % | 50,35 % |

| Fribourg | 66,0 % | 34,00 % | 46,59 % |

| Solothurn | 58,3 % | 41,7% | 45,04 % |

| Basel-Stadt | 67,7 % | 32,3 % | 47,15 % |

| Basel-Landschaft | 62,3 % | 44,13 % | 44,12 % |

| Schaffhausen | 50,0 % | 50,0 % | 63,71 % |

| Appenzell Ausserrhoden | 44,9 % | 55,1 % | 50,66 % |

| Appenzell Innerrhoden | 46,0 % | 54,0 % | 41,10 % |

| St. Gallen | 50,6 % | 49,4 % | 45,89 % |

| Grisons | 55,8 % | 44,2 % | 43,08 % |

| Aargau | 55,9 % | 44,1 % | 47,41 % |

| Thurgau | 50,3 % | 49,7 % | 45,54 % |

| Ticino | 64,4 % | 35,6 % | 46,96 % |

| Vaud | 73,6 % | 26,4 % | 45,99 % |

| Valais | 61,9 % | 38,1 % | 47,53 % |

| Neuchâtel | 67,0 % | 33,0 % | 42,74 % |

| Geneva | 77,8 % | 22,2 % | 47,48 % |

| Jura | 59,5 % | 40,5 % | 36,67 % |

| Swiss Confederation | 60,0 % | 40,0 % | 46,76% |

Application during the COVID-19 pandemic

On February 25, 2020, the first confirmed case of SARS COV-2 infection was reported in Switzerland. Based on Art. 6(2)(b) of the EpidA, the Federal Council issued the Ordinance 3 on Measures to Combat the Coronavirus (COVID-19), also referred to as the COVID-19 Ordinance 3, on February 28, 2020. This ordinance prohibits both public and private events with over 1000 attendees present simultaneously. On March 13 of that year, the Federal Council issued a new ordinance based on the Epidemics Act and the Federal Constitution. Consequently, the second ordinance was deemed an emergency ordinance - as opposed to the first one, which was an independent ordinance. On March 16, the Swiss situation was classified as exceptional. The Federal Council's legal basis for the COVID-19 app[29] was instructed to be drawn up and submitted to Parliament for approval based on two motions (20.3168 and 20.3144). The Council proposed an urgent amendment to the Epidemics Act, which the Assembly accepted. The amendment was effective from June 27, 2020, to June 30, 2022.[30]

On September 25, 2020, the Federal Assembly passed the Federal Act on the Statutory Principles for Federal Council Ordinances on Combating the COVID-19 Epidemic, also referred to as the COVID-19 Act. It was considered urgent and enacted on September 26, 2020.

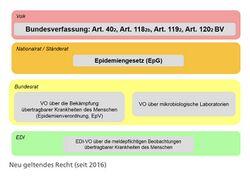

Constitutionality and delegation

The primary constitutional foundation for the Epidemics Act is Art. 118 (2)(b) of the FC, which specifies:

"It [the Confederation] shall legislate on the combating of communicable, widespread or particularly dangerous human and animal diseases."

The mentioned characteristics, including transmissibility, high prevalence, or malignancy, do not have to coexist but only occur alternately. Art. 118(3)(b) does not address the state instruments for combating these diseases. Control in this context encompasses not only preventive health measures but also preventive or health-promoting measures. Since genetically modified pathogens were included in the revised Epidemics Act of December 21, 1995, Art. 119 (2) and Art. 120 (2) of the FC, which directly address this issue, were also incorporated. In addition, Art. 40 (2) provides the basis for measures in favor of Swiss citizens living abroad.

The Epidemics Act includes rules for delegating authority to issue dependent ordinances. In simpler terms, some legislative powers are transferred from the legislature to the executive, unless they are excluded by the Federal Constitution.[31] These regulations require a greater degree of specificity than can be achieved through legislation alone. Under constitutional mandates, delegated powers should be limited to specific areas of regulation and cannot be unlimited in scope. An example of this is the reporting requirement under the Epidemics Act, which cannot be fully codified due to the need for ongoing scientific progress.

References

Notes

Citations

- ↑ "Botschaft zur Revision des Bundesgesetzes über die Bekämpfung übertragbarer Krankheiten des Menschen (Epidemiengesetz, EpG)" (in de). Bundeskanzlei. pp. 17–18. https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/fga/2011/43/de.

- ↑ Art. 6 of the EpidA

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Art. 6(1)(a) of the EpidA

- ↑ Art. 7 of the EpidA

- ↑ FOPH, Federal Office of Public Health. "Communicable Diseases Legislation – Epidemics Act, (EpidA)" (in en). https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/en/home/gesetze-und-bewilligungen/gesetzgebung/gesetzgebung-mensch-gesundheit/epidemiengesetz.html.

- ↑ Art. 10 (2) of the FC

- ↑ Art. 25 of the EpidA

- ↑ Art. 34 of the EpidA

- ↑ Art. 38 of the EpidA

- ↑ Art. 35 of the EpidA

- ↑ Art. 37 of the EpidA

- ↑ Art. 55 of the EpidA

- ↑ Art. 4 of the Influenza PandemiOordinance (Influenza-Pandemieverordnung or IPV) (in German)

- ↑ Art. 56 of the EpidA

- ↑ Art. 57 of the EpidA

- ↑ Art. 75 of the EpidA

- ↑ Art. 186 (4) of the FC

- ↑ "Botschaft zur Revision des Bundesgesetzes über die Bekämpfung übertragbarer Krankheiten des Menschen (Epidemiengesetz, EpG)" (in DE). Bundeskanzlei. https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/fga/2011/43/de.

- ↑ Art. 10a of the EpidA of December 18, 1970

- ↑ "Bundesgesetz vom 18. Dezember 1970 über die Bekämpfung übertragbarer Krankheiten des Menschen (Epidemiengesetz)" (in DE). Bundeskanzlei. https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/1974/1071_1071_1071/de.

- ↑ "Verhandlungen" (in de). Parlamentsdienste. https://www.parlament.ch/centers/documents/de/verhandlungen-10-107-2013-09-22.pdf.

- ↑ "Gesetzgebung Übertragbare Krankheiten – Epidemiengesetz (EpG)" (in de). Bundesamt für Gesundheit BAG. https://www.bag.admin.ch/dam/bag/de/dokumente/mt/epidemiengesetz/factsheet-epg-lep.pdf.download.pdf/Factsheet%20EpG_d.pdfDas.

- ↑ Art. 141 of the FC

- ↑ Bundeskanzlei BK. "Bundesgesetz über die Bekämpfung übertragbarer Krankheiten des Menschen (Epidemiengesetz, EpG) Chronologie" (in de). Bundeskanzlei. https://www.bk.admin.ch/bk/de/home/politische-rechte/pore-referenzseite.html.

- ↑ "Referendum gegen das Bundesgesetz vom 28. September 2012 über die Bekämpfung übertragbarer Krankheiten des Menschen (Epidemiengesetz, EpG). Zustandekommen" (in de). Bundeskanzlei. 2013-02-19. https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/fga/2013/274/de.

- ↑ "Bundesratsbeschluss über das Ergebnis der Volksabstimmung vom 22. September 2013 (Volksinitiative «Ja zur Aufhebung der Wehrpflicht»; Bundesgesetz über die Bekämpfung übertragbarer Krankheiten des Menschen [Epidemiengesetz, EpG]; Änderung des Bundesgesetzes über die Arbeit in Industrie, Gewerbe und Handel [Arbeitsgesetz, ArG])" (in de). Bundeskanzlei. 2013-11-18. https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/fga/2014/1286/de.

- ↑ "Epidemiengesetz" (in de). Institut für Politikwissenschaft der Universität Bern. https://swissvotes.ch/vote/573.00.

- ↑ "Vorlage Nr. 573 Resultate in den Kantonen" (in de). Bundeskanzlei. https://www.bk.admin.ch/ch/d/pore/va/20130922/can573.html.

- ↑ "Botschaft zu einer dringlichen Änderung des Epidemiengesetzes im Zusammenhang mit dem Coronavirus (Proximity-Tracing-System)" (in de). Bundeskanzlei. 2020-05-20. https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/fga/2020/1024/de.

- ↑ "Die Bundesversammlung und die Covid-19-Krise: Ein chronologischer Überblick" (in de-CH). Parlamentsdienste. 2021-06-18. https://www.parlament.ch/centers/documents/de/Faktenbericht-Bundesversammlung%20in%20der%20Covid-19%20Krise-d.pdf.

- ↑ Art. 164(2) of the FC

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Epidemics Act. |

- English page about Epidemics Act at the Federal Office of Public Health

|

KSF

KSF