Epidemiology of autism

Topic: Medicine

From HandWiki - Reading time: 32 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 32 min

The epidemiology of autism is the study of the incidence and distribution of autism spectrum disorders (ASD). A 2022 systematic review of global prevalence of autism spectrum disorders found a median prevalence of 1% in children in studies published from 2012 to 2021, with a trend of increasing prevalence over time. However, the study's 1% figure may reflect an underestimate of prevalence in low- and middle-income countries.[2][3]

Socioeconomic barriers also affect access to treatment. Due to the high cost of individualized therapies such as applied behavior analysis (ABA), speech therapy, and occupational therapy; approximately 36% of children with ASD face difficulty affording care or remain untreated.[4][5]

ASD averages a 4.3:1 male-to-female ratio in diagnosis, not accounting for ASD in gender diverse populations, which overlap disproportionately with ASD populations.[6] The number of children known to have autism has increased dramatically since the 1980s, at least partly due to changes in diagnostic practice; it is unclear whether prevalence has actually increased;[7] and as-yet-unidentified environmental risk factors cannot be ruled out.[8] In 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network reported that approximately 1 in 54 children in the United States (1 in 34 boys, and 1 in 144 girls) are diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder, based on data collected in 2016.[9] This estimate is a 10% increase from the 1 in 59 rate in 2014, 105% increase from the 1 in 110 rate in 2006 and 176% increase from the 1 in 150 rate in 2000.[9] Diagnostic criteria of ASD has changed significantly since the 1980s; for example, U.S. special-education autism classification was introduced in 1994.[7]

ASD is a complex neurodevelopmental disorder, and although what causes it is still not entirely known, efforts have been made to outline causative mechanisms and how they give rise to the disorder.[10] The risk of developing autism is increased in the presence of various prenatal factors, including advanced paternal age and diabetes in the mother during pregnancy.[11] In rare cases, autism is strongly associated with agents that cause birth defects.[12] It has been shown to be related to genetic disorders[13] and with epilepsy.[14] ASD is believed to be largely inherited, although the genetics of ASD are complex and it is unclear which genes are responsible.[7][15][16][17] ASD is also associated with several intellectual or emotional gifts, which has led to a variety of hypotheses from within evolutionary psychiatry that autistic traits have played a beneficial role over human evolutionary history.[18][19]

Other proposed causes of autism have been controversial. The vaccine hypothesis has been extensively investigated and shown to be false,[20] lacking any scientific evidence.[8] Andrew Wakefield published a small study in 1998 in the United Kingdom suggesting a causal link between autism and the trivalent MMR vaccine. After data included in the report was shown to be deliberately falsified, the paper was retracted, and Wakefield was struck off the medical register in the United Kingdom.[21][22][23]

It is problematic to compare autism rates over the last three decades, as the diagnostic criteria for autism have changed with each revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), which outlines which symptoms meet the criteria for an ASD diagnosis. In 1983, the DSM did not recognize PDD-NOS or Asperger syndrome, and the criteria for autistic disorder (AD) were more restrictive. The previous edition of the DSM, DSM-IV, included autistic disorder, childhood disintegrative disorder, PDD-NOS, and Asperger's syndrome. Due to inconsistencies in diagnosis and how much is still being learnt about autism, the most recent DSM (DSM-5) only has one diagnosis, autism spectrum disorder, which encompasses each of the previous four disorders. According to the new diagnostic criteria for ASD, one must have both struggles in social communication and interaction and restricted repetitive behaviors, interests and activities.

ASD diagnoses continue to be over four times more common among boys (1 in 34) than among girls (1 in 154), and they are reported in all racial, ethnic and socioeconomic groups. Studies have been conducted in several continents (Asia, Europe and North America) that report a prevalence rate of approximately 1 to 2 percent.[9] A 2011 study reported a 2.6 percent prevalence of autism in South Korea.[24]

Frequency

Although incidence rates measure autism prevalence directly, most epidemiological studies report other frequency measures, typically point or period prevalence, or sometimes cumulative incidence. Attention is focused mostly on whether prevalence is increasing with time.[7]

Incidence and prevalence

Epidemiology defines several measures of the frequency of occurrence of a disease or condition:[25]

- The incidence rate of a condition is the rate at which new cases occurred per person-year, for example, "2 new cases per 1,000 person-years".

- The cumulative incidence is the proportion of a population that became new cases within a specified time period, for example, "1.5 per 1,000 people became new cases during 2006".

- The point prevalence of a condition is the proportion of a population that had the condition at a single point in time, for example, "10 cases per 1,000 people at the start of 2006".

- The period prevalence is the proportion that had the condition at any time within a stated period, for example, "15 per 1,000 people had cases during 2006".

When studying how conditions are caused, incidence rates are the most appropriate measure of condition frequency as they assess probability directly. However, incidence can be difficult to measure with rarer conditions such as autism.[25] In autism epidemiology, point or period prevalence is more useful than incidence, as the condition starts long before it is diagnosed, bearing in mind genetic elements it is inherent from conception, and the gap between initiation and diagnosis is influenced by many factors unrelated to chance. Research focuses mostly on whether point or period prevalence is increasing with time; cumulative incidence is sometimes used in studies of birth cohorts.[7]

Estimation methods

The three basic approaches used to estimate prevalence differ in cost and in quality of results. The simplest and cheapest method is to count known autism cases from sources such as schools and clinics, and divide by the population. This approach is likely to underestimate prevalence because it does not count children who have not been diagnosed yet, and it is likely to generate skewed statistics because some children have better access to treatment.[26]

The second method improves on the first by having investigators examine student or patient records looking for probable cases, to catch cases that have not been identified yet. The third method, which is arguably the best, screens a large sample of an entire community to identify possible cases, and then evaluates each possible case in more detail with standard diagnostic procedures. This last method typically produces the most reliable, and the highest, prevalence estimates.[26]

Frequency estimates

Estimates of the prevalence of autism vary widely depending on diagnostic criteria, age of children screened, and geographical location.[27] Most recent reviews tend to estimate a prevalence of 1–2 per 1,000 for classic autism and close to 27.6 per 1,000 for ASD;[28] PDD-NOS is the vast majority of ASD, Asperger syndrome is about 0.3 per 1,000 and the atypical forms childhood disintegrative disorder and Rett syndrome are much rarer.[29]

A 2006 study of nearly 57,000 British nine- and ten-year-olds reported a prevalence of 3.89 per 1,000 for autism and 11.61 per 1,000 for ASD; these higher figures could be associated with broadening diagnostic criteria.[30] Studies based on more detailed information, such as direct observation rather than examination of medical records, identify higher prevalence; this suggests that published figures may underestimate ASD's true prevalence.[31] A 2009 study of the children in Cambridgeshire, England used different methods to measure prevalence, and estimated that 40% of ASD cases go undiagnosed, with the two least-biased estimates of true prevalence being 11.3 and 15.7 per 1,000.[32]

A 2009 U.S. study based on 2006 data estimated the prevalence of ASD in eight-year-old children to be 9.0 per 1,000 (approximate range 8.6–9.3).[33] A 2009 report based on the 2007 Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey by the National Health Service determined that the prevalence of ASD in adults was approximately 1% of the population, with a higher prevalence in males and no significant variation between age groups;[34] these results suggest that prevalence of ASD among adults is similar to that in children and rates of autism are not increasing.[35]

Increased diagnoses over time

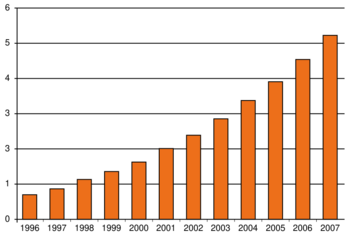

Attention has been focused on whether the prevalence of autism is increasing with time. Earlier prevalence estimates were lower, centering at about 0.5 per 1,000 for autism during the 1960s and 1970s and about 1 per 1,000 in the 1980s, as opposed to today's 23 per 1000.[7][36]

The number of reported cases of autism increased dramatically in the 1990s and 2000s, prompting ongoing investigations into two main potential reasons:[37]

- More children may have autism; that is, the true frequency of autism may have increased.

- The apparent increase may be illusory, caused by some form of measurement bias such as improved diagnosis or widened diagnostic criteria.

Increased diagnoses as measurement bias

Many explanations suggest that the increased diagnosis of autism might be caused by changes in the definition of the condition, improved methods of diagnosis, decreased stigma, and widespread mainstream public awareness of the condition.[38]

- There may be more complete pickup of autism (case finding), as a result of increased awareness and funding. For example, attempts to sue vaccine companies may have increased case-reporting.

- The diagnosis may be applied more broadly than before, as a result of the changing definition of the disorder, particularly changes in DSM-III-R and DSM-IV.

- An editorial error in the description of the PDD-NOS category of Autism Spectrum Disorders in the DSM-IV, in 1994, inappropriately broadened the PDD-NOS construct. The error was corrected in the DSM-IV-TR, in 2000, reversing the PDD-NOS construct back to the more restrictive diagnostic criteria requirements from the DSM-III-R.[39]

- Successively earlier diagnosis in each succeeding cohort of children, including recognition in nursery (preschool), may have affected apparent prevalence but not incidence.

- A review of the "rising autism" figures compared to other disabilities in schools shows a corresponding drop in findings of intellectual disability.[40]

The reported increase is largely attributable to changes in diagnostic practices, referral patterns, availability of services, age at diagnosis, and public awareness.[7][8][1] A widely cited 2002 pilot study concluded that the observed increase in autism in California cannot be explained by changes in diagnostic criteria,[41] but a 2006 analysis found that special education data poorly measured prevalence because so many cases were undiagnosed, and that the 1994–2003 U.S. increase was associated with declines in other diagnostic categories, indicating that diagnostic substitution had occurred.[40] A small 2008 study found that a significant number (40%) of people diagnosed with pragmatic language impairment as children in previous decades would now be given a diagnosis as autism.[42] A study of all Danish children born in 1994–99 found that children born later were more likely to be diagnosed at a younger age, supporting the argument that apparent increases in autism prevalence were at least partly due to decreases in the age of diagnosis.[43]

A 2007 study that modeled autism incidence found that broadened diagnostic criteria, diagnosis at a younger age, and improved efficiency of case ascertainment, can produce an increase in autism diagnoses ranging up to 29-fold depending on the frequency measure, suggesting that methodological factors may explain what appears to be an increase in autism over time.[44] This observation is often mistakenly described as an "autism epidemic".[45]

Increased diagnosis as potentially increased rates of autism

Other sources suggest that, beyond mere measurement bias, autism is in fact becoming more common. Several environmental factors have been proposed to support the hypothesis that the actual frequency of autism has increased. These include certain foods, infectious disease, and herbicides.

Although it is unknown whether autism's frequency has increased, sources suggest such an increase, if real, would suggest environmental factors might be responsible.[49]

A 2009 study of California data found that the reported incidence of autism rose 7- to 8-fold from the early 1990s to 2007, and that changes in diagnostic criteria, inclusion of milder cases, and earlier age of diagnosis probably explain only a 4.25-fold increase; the study did not quantify the effects of wider awareness of autism, increased funding, and expanding support options resulting in parents' greater motivation to seek services.[50] Another 2009 California study found that the reported increases are unlikely to be explained by changes in how qualifying condition codes for autism were recorded.[51]

In 2014, a study reported a correlation between the herbicide glyphosate in the US food supply and autism diagnosis rates.[52] The graph comparing the two trends was widely shared, but skeptics cast doubt on the claim.[48]

Misinformation about heavy metals in vaccines

Beginning in the 1970s, the United States mounted a major effort to reduce environmental heavy metal exposure. Amid a campaign of lead abatement, lead paint was banned, leaded fuel was phased out, and drinking water became subject to testing for safe levels of heavy metals. Simultaneously, the nation began increased regulation of mercury, and by 2003, states had begun to ban thermometers containing the element. Despite the decrease in environmental heavy metals, autism diagnosis rates continued to rise.

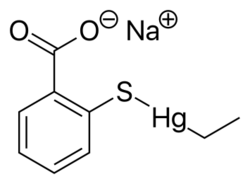

In the 1990s, some fringe sources speculated that autism might stem from the mercury-containing compound thiomersal which was used, at that time, in some vaccines.[8] By 2001, the compound had been removed from vaccines, but autism diagnosis rates continued to climb unabated.

There are claims that there is an "autism epidemic" based on the increased number of diagnosed cases. Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has claimed that there is an "autism epidemic", which he calls a "holocaust",[53] and he has repeated the false claim that autism is caused by vaccines. He has been heavily criticized for such statements.[54][55][56][57]

Geographical frequency

Africa

The prevalence of autism in Africa is unknown.[58]

The Americas

The prevalence of autism in the Americas overall is unknown.

Canada

The Canadian government reported in 2019 that 1 in 50 children were diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder.[59] However, preliminary results of an epidemiological study conducted at Montreal Children's Hospital in the 200–2004 school year found a prevalence rate of 0.68% (or 1 per 147).[60]

A 2001 review of the medical research conducted by the Public Health Agency of Canada concluded that there was no link between MMR vaccine and either inflammatory bowel disease or autism.[61] The review noted, "An increase in cases of autism was noted by year of birth from 1979 to 1992; however, no incremental increase in cases was observed after the introduction of MMR vaccination."[61] After the introduction of MMR, "A time trend analysis found no correlation between prevalence of MMR vaccination and the incidence of autism in each birth cohort from 1988 to 1993."[61]

United States

According to a report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2020, 1 in 36 children have ASD (27.6 in every 1,000).[28] The number of diagnosed cases of autism grew dramatically in the U.S. in the 1990s and have continued in the 2000s. For the 2006 surveillance year, identified ASD cases were an estimated 9.0 per 1000 children aged 8 years (95% confidence interval [CI] = 8.6–9.3).[33] These numbers measure what is sometimes called "administrative prevalence", that is, the number of known cases per unit of population, as opposed to the true number of cases.[40] This prevalence estimate rose 57% (95% CI 27%–95%) from 2002 to 2006.[33]

The National Health Interview Survey for 2014–2016 studied 30,502 US children and adolescents and found the weighted prevalence of ASD was 2.47% (24.7 per 1,000); 3.63% in boys and 1.25% in girls. Across the 3-year reporting period, the prevalence was 2.24% in 2014, 2.41% in 2015, and 2.76% in 2016.[62]

The number of new cases of autism spectrum disorder in Caucasian boys is roughly 50% higher than found in Hispanic children, and approximately 30% more likely to occur than in Non-Hispanic white children in the United States.[7][63]

A further study in 2006 concluded that the apparent rise in administrative prevalence was the result of diagnostic substitution, mostly for findings of intellectual disability and learning disabilities.[40] "Many of the children now being counted in the autism category would probably have been counted in the mental retardation or learning disabilities categories if they were being labeled 10 years ago instead of today", said researcher Paul Shattuck of the Waisman Center at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, in a statement.[64]

A population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota county found that the cumulative incidence of autism grew eightfold from the 1980–83 period to the 1995–97 period. The increase occurred after the introduction of broader, more-precise diagnostic criteria, increased service availability, and increased awareness of autism.[65] During the same period, the reported number of autism cases grew 22-fold in the same location, suggesting that counts reported by clinics or schools provide misleading estimates of the true incidence of autism.[66]

Venezuela

A 2008 study in Venezuela reported a prevalence of 1.1 per 1,000 for autism and 1.7 per 1,000 for ASD.[67]

Asia

China

A journal reports that the median prevalence of ASD among 2–6-year-old children who are reported in China from 2000 upwards was 10.3/10,000.[68]

Hong Kong

A 2008 Hong Kong study reported an ASD incidence rate similar to those reported in Australia and North America, and lower than Europeans. It also reported a prevalence of 1.68 per 1,000 for children under 15 years.[69]

Japan

A 2005 study of a part of Yokohama with a stable population of about 300,000 reported a cumulative incidence to age 7 years of 48 cases of ASD per 10,000 children in 1989, and 86 in 1990. After the vaccination rate of the triple MMR vaccine dropped to near zero and was replaced with MR and M vaccine, the incidence rate grew to 97 and 161 cases per 10,000 children born in 1993 and 1994, respectively, indicating that the combined MMR vaccine did not cause autism.[70] A 2004 Japanese autism association reported that about 360.000 people have typical Kanner-type autism.

Australia

Across all ages, 1 in 70 Australians identify as being autistic. 1 in 23 children (or 4.36%) aged 7 to 14 years have an autism diagnosis.[71]

Middle East

Israel

A 2009 study reported that the annual incidence rate of Israeli children with a diagnosis of ASD receiving disability benefits rose from zero in 1982–1984 to 190 per million in 2004. It was not known whether these figures reflected true increases or other factors such as changes in diagnostic measures.[72]

Saudi Arabia

Studies of autism frequency have been particularly rare in the Middle East. One rough estimate is that the prevalence of autism in Saudi Arabia is 18 per 10,000, slightly higher than the 13 per 10,000 reported in developed countries.[73](compared to 168 per 10,000 in the USA)

Europe

Denmark

In 1992, thiomersal-containing vaccines were removed in Denmark. A study at Aarhus University indicated that during the chemical's usage period (up through 1990), there was no trend toward an increase in the incidence of autism. Between 1991 and 2000 the incidence increased, including among children born after the discontinuation of thimerosal.[74]

France

France made autism the national focus for the year 2012 and the Health Ministry estimated the rate of autism in 2012 to have been 0.67%, i.e. 1 in 150.[75]

Eric Fombonne made some studies in the years 1992 and 1997. He found a prevalence of 16 per 10,000 for the global pervasive developmental disorder (PDD).[76][77] The INSERM found a prevalence of 27 per 10,000 for the ASD and a prevalence of 9 per 10,000 for the early infantile autism in 2003.[78] Those figures are considered as underrated as the WHO gives figures between 30 and 60 per 10,000.[79] The French Minister of Health gives a prevalence of 4.9 per 10,000 on its website but it counts only early infantile autism.[80]

Germany

A 2008 study in Germany found that inpatient admission rates for children with ASD increased 30% from 2000 to 2005, with the largest rise between 2000 and 2001 and a decline between 2001 and 2003. Inpatient rates for all mental disorders also rose for ages up to 15 years, so that the ratio of ASD to all admissions rose from 1.3% to 1.4%.[81]

Norway

A 2009 study in Norway reported prevalence rates for ASD ranging from 0.21% to 0.87%, depending on assessment method and assumptions about non-response, suggesting that methodological factors explain large variances in prevalence rates in different studies.[82]

United Kingdom

The incidence and changes in incidence with time are unclear in the United Kingdom.[83] The reported autism incidence in the UK rose starting before the first introduction of the MMR vaccine in 1989.[84] However, a perceived link between the two arising from the results of a fraudulent scientific study has caused considerable controversy, despite being subsequently disproved.[85] A 2004 study found that the reported incidence of pervasive developmental disorders in a general practice research database in England and Wales grew steadily during 1988–2001 from 0.11 to 2.98 per 10,000 person-years, and concluded that much of this increase may be due to changes in diagnostic practice.[86]

Genetics

As late as the mid-1970s there was little evidence of a genetic role in autism; evidence from genetic epidemiology studies now suggests that it is one of the most heritable of all psychiatric conditions.[87] The first studies of twins estimated heritability to be more than 90%; in other words, that genetics explains more than 90% of autism cases.[16] When only one identical twin is autistic, the other often has learning or social disabilities. For adult siblings, the risk of having one or more features of the broader autism phenotype might be as high as 30%,[88] much higher than the risk in controls.[89] About 10–15% of autism cases have an identifiable Mendelian (single-gene) condition, chromosome abnormality, or other genetic syndrome,[88] and ASD is associated with several genetic disorders.[13]

Since heritability is less than 100% and symptoms vary markedly among identical twins with autism, environmental factors are most likely a significant cause as well. If some of the risk is due to gene-environment interaction the 90% heritability may be too high;[7] However, in 2017, the largest study, including over three million participants, estimated the heritability at 83%.[15]

Genetic linkage analysis has been inconclusive; many association analyses have had inadequate power.[90] Studies have examined more than 100 candidate genes; many genes must be examined because more than a third of genes are expressed in the brain and there are few clues on which are relevant to autism.[7]

Causative factors

Template:Summary too long A few studies have found an association between autism and frequent use of acetaminophen (e.g. Tylenol, Paracetamol) by the mother during pregnancy.[91][92] Autism is also associated with several other prenatal factors, including advanced age in either parent, and diabetes, bleeding, or use of psychiatric drugs in the mother during pregnancy.[11] Autism was found to be indirectly linked to prepregnancy obesity and low weight mothers.[93] It is not known whether mutations that arise spontaneously in autism and other neuropsychiatric disorders come mainly from the mother or the father, or whether the mutations are associated with parental age.[94] However, recent studies have identified advancing paternal age as a significant indicator for ASD.[95] Increased chance of autism has also been linked to rapid "catch-up" growth for children born to mothers who had unhealthy weight at conception.[93]

A large 2008 population study of Swedish parents of children with autism found that the parents were more likely to have been hospitalized for a mental disorder, that schizophrenia was more common among the mothers and fathers, and that depression and personality disorders were more common among the mothers.[96]

It is not known how many siblings of autistic individuals are themselves autistic. Several studies based on clinical samples have given quite different estimates, and these clinical samples differ in important ways from samples taken from the general community.[97]

Autism has also been shown to cluster in urban neighborhoods of high socioeconomic status. One study from California found a three to fourfold increased risk of autism in a small 30 by 40 km region centered on West Hollywood, Los Angeles.[98]

Sex and gender differences

Recent analyses continue to show a notable sex disparity in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) diagnoses. In the United States, ASD prevalence is estimated at approximately 43.0 per 1,000 males compared to 11.4 per 1,000 females, yielding a male-to-female ratio of about 3.8 to 1.[99]

Research suggests several factors may contribute to this difference. Biological theories propose that females may have a higher tolerance to genetic or hormonal risk factors due to possessing two X chromosomes, which provides some protection against X-linked mutations associated with ASD.[100]

Social and behavioral explanations indicate that females with ASD often "camouflage" or mask their symptoms, making diagnosis more difficult and leading to underreporting among girls.[101]

RORA deficiency may explain some of the difference in frequency between males and females. RORA protein levels are higher in the brains of typically developing females compared to typically developing males, providing females with a buffer against RORA deficiency. This is known as the female protective effect. RORA deficiency has previously been proposed as one factor that may make males more vulnerable to autism.[102]

There is a statistically notable overlap between ASD populations and gender diverse populations.[6]

Other findings

There exists behavioral differences and differences in brain structures between males and females with autism. Females often either mask their symptoms more (called camouflaging) or need to display more prominent symptoms to receive a diagnosis.[103][104][105] Males tend to demonstrate common symptoms of autism such as repetitive and restricted behaviors more so than females. This difference is hypothesized to be part of why females are more likely to be underdiagnosed.

Vaccines

A common misconception is that vaccinations are the cause of children developing ASD. This is partly due to the concern of a former ingredient called thiomersal, which is a substance that contains mercury.[106] Scientific literature demonstrates that there is no causal link between thimerosal and ASD. Though the ingredient is not as prevalent in vaccines anymore, there is still concern about the link between autism and vaccinations, but there is no evidence to support this notion.

Environmental chemical exposure

One hypothesis is that exposure to environmental chemicals before the age of two months contributes to development of ASD.[107]

Human studies have mainly focused on particulate matter or mercury. Other studies investigated the effects of pollutants in the air or lead. Additionally, studies involving rodent animal models also investigated the effects of chlorpyrifos. Research suggests that some genes involved in ASD may be targeted by environmental chemicals and pollutants.[107][108]

One longitudinal study had found elevated levels of perfluorodecanoic acid and zearalenone in the cord serum of children that later developed autism, suggesting that prenatal exposure may affect ASD.[109]

Related brain structures

Key symptoms of autism spectrum disorder are impaired social and communication abilities and having a narrow scope of interest and repeated behaviors.[110] An impairment of language used to be a key diagnostic factor, but research has led to categorizing this symptom as a specifier. One scoping review has determined multiple brain structures that appear to play a role in language related symptoms in autism spectrum disorder. For example, having a larger sized right inferior frontal gyrus is correlated with those diagnosed with autism, specifically categorized in the language impairment subgroup (but not in those without).[110][111] Some research yields conflicting results however related to different structures and total language scores, in which a possible factor for this could be age.

As for temporal regions, increased rightward radial diffusivity might have an association with receptive language scores.[110][112] Research concerning the planum temporale and its role in language has been inconclusive.[110] The cerebellum may also be a factor in whether a person has language impairment or not.[113][111]

Symptom management

Much research centered around those with ASD that have impaired communication and seeking improvement in social interaction often investigate the use of psychosocial interventions.[114] However, other research looks to pharmacology for treatment. Behavioral management therapy is another potential option.[115] Overall however, treatment options are still in development.

Comorbid conditions

Autism is associated with several other conditions:

- Genetic disorders. About 10–15% of autism cases have an identifiable Mendelian (single-gene) condition, chromosome abnormality, or other genetic syndrome,[88] and ASD is associated with several genetic disorders.[13]

- Intellectual disability. The fraction of autistic individuals who also meet criteria for intellectual disability has been reported as anywhere from 25% to 70%, a wide variation illustrating the difficulty of assessing autistic intelligence.[116]

- Gastrointestinal disease are a common comorbidity in patients with autism spectrum disorders, even though the underlying mechanisms are largely unknown. The most common gastrointestinal symptoms reported are abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea and bloating, reported in at least 25 percent of patients.[117]

- Anxiety disorders are common among children with ASD, although there are no firm data.[118] Symptoms include generalized anxiety and separation anxiety,[119] and are likely affected by age, level of cognitive functioning, degree of social impairment, and ASD-specific difficulties. Many anxiety disorders, such as social phobia, are not commonly diagnosed in people with ASD because such symptoms are better explained by ASD itself, and it is often difficult to tell whether symptoms such as compulsive checking are part of ASD or a co-occurring anxiety problem. The prevalence of anxiety disorders in children with ASD has been reported to be anywhere between 11% and 84%.[118]

- Epilepsy, with variations in risk of epilepsy due to age, cognitive level, and type of language disorder; 5–38% of children with autism have comorbid epilepsy, and only 16% of these have remission in adulthood.[14]

- Several metabolic defects, such as phenylketonuria, are associated with autistic symptoms.[120]

- Minor physical anomalies are significantly increased in the autistic population.[121]

- Preempted diagnoses. Although the DSM-IV rules out concurrent diagnosis of many other conditions along with autism, the full criteria for ADHD, Tourette syndrome, and other of these conditions are often present and these comorbid diagnoses are increasingly accepted.[122] A 2008 study found that nearly 70% of children with ASD had at least one psychiatric disorder, including nearly 30% with social anxiety disorder and similar proportions with ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder.[123] Childhood-onset schizophrenia, a rare and severe form, is another preempted diagnosis whose symptoms are often present along with the symptoms of autism.[124]

COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic may have impacted the current number of diagnoses. More assessments for ASD occurred among 4-year-olds than the current 8-year-olds when they were 4 years of age prior to the pandemic.[125] After the pandemic, the rate of current assessments has dropped, leading to possible delayed identification of ASD.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Prevalence and changes in diagnostic practice:

- "The prevalence of autism". JAMA 289 (1): 87–9. January 2003. doi:10.1001/jama.289.1.87. PMID 12503982.

- "The epidemiology of autistic spectrum disorders: is the prevalence rising?". Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews 8 (3): 151–61. 2002. doi:10.1002/mrdd.10029. PMID 12216059.

- ↑ Zeidan, Jinan; Fombonne, Eric; Scorah, Julie; Ibrahim, Alaa; Durkin, Maureen S.; Saxena, Shekhar; Yusuf, Afiqah; Shih, Andy et al. (May 2022). "Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update". Autism Research 15 (5): 778–790. doi:10.1002/aur.2696. PMID 35238171.

- ↑ "Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders". Autism Research 5 (3): 160–79. June 2012. doi:10.1002/aur.239. PMID 22495912.

- ↑ KyoCare. (2024). The financial cost of autism therapy and access challenges. Retrieved October 25, 2025, from https://kyocare.com/autism-therapy-cost

- ↑ Littman, R., et al. (2023). Economic and access disparities among U.S. children receiving ASD-related services. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 44(2), 95–107. https://doi.org/10.xxxxx/jdbp.2023.01234

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Largest study to date confirms overlap between autism and gender diversity". 2020-09-14. https://www.spectrumnews.org/news/largest-study-to-date-confirms-overlap-between-autism-and-gender-diversity/.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 "The epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders". Annual Review of Public Health 28: 235–58. 2007. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144007. PMID 17367287.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 "Incidence of autism spectrum disorders: changes over time and their meaning". Acta Paediatrica 94 (1): 2–15. January 2005. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2005.tb01779.x. PMID 15858952.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 CDC (2020-03-27). "Data and Statistics on Autism Spectrum Disorder | CDC" (in en-us). https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html.

- ↑ "A Unifying Theory for Autism: The Pathogenetic Triad as a Theoretical Framework". Frontiers in Psychiatry 12. November 2021. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.767075. PMID 34867553.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Prenatal risk factors for autism: comprehensive meta-analysis". The British Journal of Psychiatry 195 (1): 7–14. July 2009. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.108.051672. PMID 19567888.

- ↑ "The teratology of autism". International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience 23 (2–3): 189–99. 2005. doi:10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.11.001. PMID 15749245.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 "Childhood autism and associated comorbidities". Brain & Development 29 (5): 257–72. June 2007. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2006.09.003. PMID 17084999.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "The autism-epilepsy connection". Epilepsia 48 (Suppl 9): 33–5. 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01399.x. PMID 18047599.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Sandin, S.; Lichtenstein, P.; Kuja-Halkola, R.; Hultman, C.; Larsson, H.; Reichenberg, A. (26 September 2017). "The Heritability of Autism Spectrum Disorder". JAMA 318 (12): 1182–1184. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.12141. PMID 28973605.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "The genetics of autistic disorders and its clinical relevance: a review of the literature". Molecular Psychiatry 12 (1): 2–22. January 2007. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001896. PMID 17033636.

- ↑ "Etiology of infantile autism: a review of recent advances in genetic and neurobiological research". Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience 24 (2): 103–15. March 1999. PMID 10212552.

- ↑ The pattern seekers: how autism drives human invention. Basic Books. 10 November 2020. ISBN 978-1-5416-4713-8. OCLC 1204602315.

- ↑ "Autism As a Disorder of High Intelligence". Frontiers in Neuroscience 10: 300. 2016-06-30. doi:10.3389/fnins.2016.00300. PMID 27445671.

- ↑ "Vaccines are not associated with autism: an evidence-based meta-analysis of case-control and cohort studies". Vaccine 32 (29): 3623–9. June 2014. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.04.085. PMID 24814559.

- ↑ "Wakefield's article linking MMR vaccine and autism was fraudulent". BMJ 342. January 2011. doi:10.1136/bmj.c7452. PMID 21209060.

- ↑ "Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children". Lancet 351 (9103): 637–41. February 1998. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(97)11096-0. PMID 9500320.

- ↑ "How disgraced anti-vaxxer Andrew Wakefield was embraced by Trump's America". The Guardian. 18 July 2018. https://theguardian.com/society/2018/jul/18/how-disgraced-anti-vaxxer-andrew-wakefield-was-embraced-by-trumps-america.

- ↑ "Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders in a total population sample". The American Journal of Psychiatry 168 (9): 904–12. September 2011. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10101532. PMID 21558103.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "Quantifying diseases in populations". Epidemiology for the Uninitiated (4th ed.). BMJ. 1997. ISBN 0-7279-1102-3.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "The rise in autism and the mercury myth". Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing 22 (1): 51–3. February 2009. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6171.2008.00152.x. PMID 19200293.

- ↑ "Systematic review of prevalence studies of autism spectrum disorders". Archives of Disease in Childhood 91 (1): 8–15. January 2006. doi:10.1136/adc.2004.062083. PMID 15863467. PMC 2083083. http://autismresearchcentre.com/docs/papers/2006_Williams_etal_ADC.pdf.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 CDC (2024-01-10). "Data and Statistics on Autism Spectrum Disorder | CDC". https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html.

- ↑ "Epidemiology of autistic disorder and other pervasive developmental disorders". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 66 (Suppl 10): 3–8. 2005. PMID 16401144.

- ↑ "Prevalence of disorders of the autism spectrum in a population cohort of children in South Thames: the Special Needs and Autism Project (SNAP)". Lancet 368 (9531): 210–5. July 2006. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69041-7. PMID 16844490.

- ↑ "Autism spectrum disorders: clinical and research frontiers". Archives of Disease in Childhood 93 (6): 518–23. June 2008. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.115337. PMID 18305076.

- ↑ "Prevalence of autism-spectrum conditions: UK school-based population study". The British Journal of Psychiatry 194 (6): 500–9. June 2009. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.108.059345. PMID 19478287.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 "Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders - Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, United States, 2006". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries 58 (10): 1–20. December 2009. PMID 20023608. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss5810a1.htm.

- ↑ Autism Spectrum Disorders in adults living in households throughout England: Report from the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2007 (Report). NHS Information Centre for health and social care. 2009. http://www.ic.nhs.uk/webfiles/publications/mental%20health/mental%20health%20surveys/APMS_Autism_report_standard_20_OCT_09.pdf. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- ↑ "Autism just as common in adults, so MMR jab is off the hook". Guardian. 2009-09-22. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2009/sep/22/autism-rate-mmr-vaccine.

- ↑ "ASD Data and Statistics". https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html.

- ↑ "Notes on the prevalence of autism spectrum disorders". National Autistic Society. 1999. http://www.nas.org.uk/nas/jsp/polopoly.jsp?d=364&a=2618.

- ↑ "Autism diagnoses are on the rise – but autism itself may not be". 10 May 2025. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20250509-why-autism-diagnoses-are-on-the-rise.

- ↑ "Clarification of the definition of Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified". http://www.psychiatry.org/practice/dsm/practice-relevant-changes-to-the-dsm-iv-tr.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 "The contribution of diagnostic substitution to the growing administrative prevalence of autism in US special education". Pediatrics 117 (4): 1028–37. April 2006. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-1516. PMID 16585296.

- Lay summary in: Devitt, Terry. "Data provides misleading picture of autism". University of Wisconsin–Madison. https://news.wisc.edu/data-provides-misleading-picture-of-autism/.

- ↑ "Report to the legislature on the principal findings of the epidemiology of autism in California: a comprehensive pilot study". 2002. http://www.ucdmc.ucdavis.edu/mindinstitute/newsroom/study_final.pdf.

- ↑ "Autism and diagnostic substitution: evidence from a study of adults with a history of developmental language disorder". Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 50 (5): 341–5. May 2008. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.02057.x. PMID 18384386.

- ↑ "Autism prevalence trends over time in Denmark: changes in prevalence and age at diagnosis". Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 162 (12): 1150–6. December 2008. doi:10.1001/archpedi.162.12.1150. PMID 19047542.

- ↑ "The autism epidemic: fact or artifact?". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 46 (6): 721–730. June 2007. doi:10.1097/chi.0b013e31804a7f3b. PMID 17513984.

- ↑ Gerrard, Rachel Burr (February 10, 2022). "There's no autism epidemic. But there is an autism diagnosis epidemic". https://www.statnews.com/2022/02/10/theres-no-autism-epidemic-but-there-is-an-autism-diagnosis-epidemic/.

- ↑ Seneff, Stephanie; Kyriakopoulos, Anthony M.; Nigh, Greg (2024). "Is autism a PIN1 deficiency syndrome? A proposed etiological role for glyphosate". Journal of Neurochemistry 168 (9): 2124–2146. doi:10.1111/jnc.16140. PMID 38808598.

- ↑ "Is the Weed Killer Glyphosate Harming Your Health?". 26 December 2017. https://www.autismparentingmagazine.com/weed-killer-glyphosate-harming-your-health/.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 "A Skeptical Guide to Glyphosate: Toolkit for Ten Common Claims | Skeptical Inquirer". 20 August 2024. https://skepticalinquirer.org/exclusive/a-skeptical-guide-to-glyphosate-toolkit-for-ten-common-claims/.

- ↑ "Tracing the origins of autism: a spectrum of new studies". Environmental Health Perspectives 114 (7): A412-8. July 2006. doi:10.1289/ehp.114-a412. PMID 16835042. PMC 1513312. http://www.ehponline.org/members/2006/114-7/focus.html.

- ↑ "The rise in autism and the role of age at diagnosis". Epidemiology 20 (1): 84–90. January 2009. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181902d15. PMID 19234401.

- Lay summary in: "What Is Autism?". 2009-01-08. http://www.webmd.com/brain/autism/news/20090108/autism-cases-rise.

- ↑ "Investigation of shifts in autism reporting in the California Department of Developmental Services". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 39 (10): 1412–9. October 2009. doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0754-z. PMID 19479197.

- ↑ Swanson, Nancy & Leu, Andre & Abrahamson, Jon & Wallet, Bradley. (2014). Genetically engineered crops, glyphosate and the deterioration of health in the United States of America. Journal of Organic Systems. 9. 6-37.

- ↑ White, Jeremy B. (April 7, 2015). "Robert Kennedy Jr. warns of vaccine-linked 'holocaust'". The Sacramento Bee. https://www.sacbee.com/news/politics-government/capitol-alert/article17814440.html.

- ↑ Kessler, Glenn (April 25, 2025). "RFK Jr.'s absurd statistic on the spike in chronic diseases in the U.S.". The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2025/04/25/rfk-jr-chronic-diseases-false/. "He's long been a purveyor of the fiction that vaccines cause autism, and one of his key points of evidence is that the percentage of people with autism has increased. But the percentage of people diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder has gone up mainly because of expanded definitions and better detection. There is no blood test for autism, so a diagnosis is based on observations of a person's behavior. Indeed, while autism diagnoses have increased, those of intellectual disability have decreased, indicating that previously, children may have been misdiagnosed with other conditions."

- ↑ Wadman, Meredith (April 16, 2025). "Claiming autism 'epidemic,' RFK Jr. describes NIH initiative to find environmental causes". https://www.science.org/content/article/claiming-autism-epidemic-rfk-jr-describes-nih-initiative-find-environmental-causes.

- ↑ Geddie, Becky (April 11, 2025). "Statement on Robert F. Kennedy Jr.'s Comments Regarding the Cause of Autism and Misleading Deadline". https://autismsociety.org/statement-on-robert-f-kennedy-jr-s-comments-regarding-the-cause-of-autism-and-misleading-deadline/.

- ↑ Wendling, Mike (April 11, 2025). "RFK Jr pledges to find the cause of autism 'by September'". https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cj0z9nmzvdlo.

- ↑ "Etiologies of autism in a case-series from Tanzania". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 36 (8): 1039–51. November 2006. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0143-9. PMID 16897390.

- ↑ Canada, Public Health Agency of (2022-02-03). "Autism spectrum disorder: Highlights from the 2019 Canadian health survey on children and youth". https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/autism-spectrum-disorder-canadian-health-survey-children-youth-2019.html.

- ↑ Norris, Sonya; Paré, Jean-Rodrigue; Starky, Sheena (January 26, 2006). "Childhood autism in Canada: some issues relating to behavioural intervention" (PDF). Ottawa: Library of Parliament; Parliamentary Research Branch. https://www.publications.gc.ca/site/eng/295807/publication.html.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 Strauss, B; Bigham, M (2001). "Does measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccination cause inflammatory bowel disease and autism?". Canada Communicable Disease Report 27 (8): 65–72. ISSN 1481-8531. PMID 11338656.

- ↑ "Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among US Children and Adolescents, 2014-2016". JAMA 319 (1): 81–82. January 2018. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.17812. PMID 29297068.

- ↑ "ASD Data and Statistics". https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html.

- ↑ Devitt, Terry (3 April 2006). "Data provides misleading picture of autism". University of Wisconsin–Madison. https://news.wisc.edu/data-provides-misleading-picture-of-autism/.

- ↑ "The incidence of autism in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976-1997: results from a population-based study". Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 159 (1): 37–44. January 2005. doi:10.1001/archpedi.159.1.37. PMID 15630056.

- ↑ "The incidence of clinically diagnosed versus research-identified autism in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976-1997: results from a retrospective, population-based study". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 39 (3): 464–70. March 2009. doi:10.1007/s10803-008-0645-8. PMID 18791815.

- ↑ "Epidemiological findings of pervasive developmental disorders in a Venezuelan study". Autism 12 (2): 191–202. March 2008. doi:10.1177/1362361307086663. PMID 18308767.

- ↑ "A review of the prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Asia". Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 4 (2): 156–167. April 2010. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2009.10.003.

- ↑ "Epidemiological study of autism spectrum disorder in China". Journal of Child Neurology 23 (1): 67–72. January 2008. doi:10.1177/0883073807308702. PMID 18160559.

- ↑ "No effect of MMR withdrawal on the incidence of autism: a total population study". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 46 (6): 572–9. June 2005. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01425.x. PMID 15877763.

- ↑ "Understanding autism prevalence". 2023. https://taxpolicy.crawford.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/publication/taxstudies_crawford_anu_edu_au/2023-11/complete_wp_m_ranjan_nov_2023.pdf.

- ↑ "Time trends in reported autistic spectrum disorders in Israel, 1972-2004". The Israel Medical Association Journal 11 (1): 30–3. January 2009. PMID 19344009. http://www.ima.org.il/imaj/ar09jan-05.pdf.

- ↑ "Autism in Saudi Arabia: presentation, clinical correlates and comorbidity". Transcultural Psychiatry 46 (2): 340–7. June 2009. doi:10.1177/1363461509105823. PMID 19541755.

- ↑ "Thimerosal and the occurrence of autism: negative ecological evidence from Danish population-based data". Pediatrics 112 (3 Pt 1): 604–6. September 2003. doi:10.1542/peds.112.3.604. PMID 12949291.

- ↑ "Autisme Grande Cause". http://www.autismegrandecause2012.fr/.

- ↑ "Prevalence of infantile autism in four French regions". Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 27 (4): 203–10. August 1992. doi:10.1007/bf00789007. PMID 1411750.

- ↑ "Autism and associated medical disorders in a French epidemiological survey". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36 (11): 1561–9. November 1997. doi:10.1016/S0890-8567(09)66566-7. PMID 9394941.

- ↑ Expertise collective. Troubles mentaux. Dépistage et prévention chez l'enfant et chez l'adolescent. Inserm, 2003, 8

- ↑ "Plan autisme 2008–2010: Construire une nouvelle étape de la politique des troubles envahissants du développement (TED) et en particulier de l'autisme" (in French). Republic of France. http://www.sante-sports.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/Plan_autisme_2008-2010.pdf.

- ↑ "Jean-François Chossy, La situation des autistes en France, besoins et perspectives, rapport remis au Premier ministre, La Documentation française: Paris, Septembre 2003.". http://lesrapports.ladocumentationfrancaise.fr/BRP/034000590/0000.pdf.

- ↑ "Trends in autism spectrum disorder referrals". Epidemiology 19 (3): 519–20. May 2008. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e31816a9e13. PMID 18414094.

- ↑ "The prevalence of autism spectrum disorders: impact of diagnostic instrument and non-response bias". Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 45 (3): 319–27. March 2010. doi:10.1007/s00127-009-0087-4. PMID 19551326.

- ↑ "Incidence of autism". National Autistic Society. 2004. http://www.autism.org.uk/nas/jsp/polopoly.jsp?a=5576.

- ↑ "Mumps, measles, and rubella vaccine and the incidence of autism recorded by general practitioners: a time trend analysis". BMJ 322 (7284): 460–3. February 2001. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7284.460. PMID 11222420.

- ↑ "MMR doctor Andrew Wakefield fixed data on autism". The Sunday Times (London). 8 February 2009. http://www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/public/news/article148992.ece.

- ↑ "Rate of first recorded diagnosis of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders in United Kingdom general practice, 1988 to 2001". BMC Medicine 2. November 2004. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-2-39. PMID 15535890.

- ↑ "Genetic epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders". Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. 2007. pp. 157–178. ISBN 978-0-521-54957-8.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 88.2 "Genetics of autism: complex aetiology for a heterogeneous disorder". Nature Reviews. Genetics 2 (12): 943–55. December 2001. doi:10.1038/35103559. PMID 11733747.

- ↑ "A case-control family history study of autism". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 35 (5): 877–900. July 1994. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb02300.x. PMID 7962246.

- ↑ "Autism: the quest for the genes". Expert Reviews in Molecular Medicine 9 (24): 1–15. September 2007. doi:10.1017/S1462399407000452. PMID 17764594.

- ↑ "The role of oxidative stress, inflammation and acetaminophen exposure from birth to early childhood in the induction of autism". The Journal of International Medical Research 45 (2): 407–438. April 2017. doi:10.1177/0300060517693423. PMID 28415925.

- ↑ "Empirical Data Confirm Autism Symptoms Related to Aluminum and Acetaminophen Exposure". Entropy 14 (11): 2227–2253. 7 November 2012. doi:10.3390/e14112227. Bibcode: 2012Entrp..14.2227S.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 "Increased risk of very low birth weight, rapid postnatal growth, and autism in underweight and obese mothers". American Journal of Health Promotion 28 (3): 181–8. 2014. doi:10.4278/ajhp.120705-QUAN-325. PMID 23875984.

- ↑ "Male biological clock possibly linked to autism, other disorders". Nature Medicine 14 (11): 1170. November 2008. doi:10.1038/nm1108-1170a. PMID 18989289.

- ↑ "Advances in autism". Annual Review of Medicine 60 (1): 367–80. February 2009. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.60.053107.121225. PMID 19630577.

- ↑ "Parental psychiatric disorders associated with autism spectrum disorders in the offspring". Pediatrics 121 (5): e1357-62. May 2008. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-2296. PMID 18450879.

- Lay summary in: "Mental disorders in parents linked to autism in children". UNC News (Press release). 2008-05-05. Archived from the original on 2008-06-12.

- ↑ "What are infant siblings teaching us about autism in infancy?". Autism Research 2 (3): 125–37. June 2009. doi:10.1002/aur.81. PMID 19582867.

- ↑ "The spatial structure of autism in California, 1993-2001". Health & Place 16 (3): 539–46. May 2010. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.12.014. PMID 20097113.

- ↑ Maenner, M. J., et al. (2023). Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2020. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 72(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss7202a1

- ↑ Gillberg, C. (1998). The Emanuel Miller Memorial Lecture 1991: Autism and autistic-like conditions: Subclasses among disorders of empathy. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 39(3), 393–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00336

- ↑ Waizbard-Bartov, E., & Amaral, D. (2020). Gender differences in autism spectrum disorder symptoms and optimal outcome. Autism Research, 13(6), 1014–1025. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2298

- ↑ "Investigation of sex differences in the expression of RORA and its transcriptional targets in the brain as a potential contributor to the sex bias in autism". Molecular Autism 6. 2015. doi:10.1186/2040-2392-6-7. PMID 26056561.

- ↑ Shuck R. K., Flores, R. E., & Fung, L. K. (June 2019). "Brief Report: Sex/Gender Differences in Symptomology and Camouflaging in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder". J Autism Dev Disord 49 (6): 2597–2604. doi:10.1007/s10803-019-03998-y. PMID 30945091.

- ↑ Kirkovski, Melissa; Enticott, Peter G.; Fitzgerald, Paul B. (November 2013). "A review of the role of female gender in autism spectrum disorders". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 43 (11): 2584–2603. doi:10.1007/s10803-013-1811-1. ISSN 1573-3432. PMID 23525974.

- ↑ Kreiser, Nicole L.; White, Susan W. (March 2014). "ASD in females: are we overstating the gender difference in diagnosis?". Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 17 (1): 67–84. doi:10.1007/s10567-013-0148-9. ISSN 1573-2827. PMID 23836119.

- ↑ "Autism and Vaccines | Vaccine Safety | CDC". 2022-01-25. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/concerns/autism.html.

- ↑ 107.0 107.1 Pelch, Katherine E.; Bolden, Ashley L.; Kwiatkowski, Carol F. (April 2019). "Environmental Chemicals and Autism: A Scoping Review of the Human and Animal Research" (in en). Environmental Health Perspectives 127 (4): 46001. doi:10.1289/EHP4386. ISSN 0091-6765. PMID 30942615. Bibcode: 2019EnvHP.127d6001P.

- ↑ Carter, C. J.; Blizard, R. A. (2016-10-27). "Autism genes are selectively targeted by environmental pollutants including pesticides, heavy metals, bisphenol A, phthalates and many others in food, cosmetics or household products". Neurochemistry International 101: S0197–0186(16)30197–8. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2016.10.011. ISSN 1872-9754. PMID 27984170.

- ↑ Ahrens, Angelica P.; Hyötyläinen, Tuulia; Petrone, Joseph R.; Igelström, Kajsa; George, Christian D.; Garrett, Timothy J.; Orešič, Matej; Triplett, Eric W. et al. (April 2024). "Infant microbes and metabolites point to childhood neurodevelopmental disorders". Cell 187 (8): 1853–1873.e15. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2024.02.035. PMID 38574728.

- ↑ 110.0 110.1 110.2 110.3 Cermak, Carly A.; Arshinoff, Spencer; Ribeiro de Oliveira, Leticia; Tendera, Anna; Beal, Deryk S.; Brian, Jessica; Anagnostou, Evdokia; Sanjeevan, Teenu (2022-02-01). "Brain and Language Associations in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Scoping Review" (in en). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 52 (2): 725–737. doi:10.1007/s10803-021-04975-0. ISSN 1573-3432. PMID 33765302.

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 De Fossé, Lies; Hodge, Steven M.; Makris, Nikos; Kennedy, David N.; Caviness, Verne S.; McGrath, Lauren; Steele, Shelley; Ziegler, David A. et al. (December 2004). "Language-association cortex asymmetry in autism and specific language impairment". Annals of Neurology 56 (6): 757–766. doi:10.1002/ana.20275. ISSN 0364-5134. PMID 15478219.

- ↑ Lange, Nicholas; DuBray, Molly B.; Lee, Jee Eun; Froimowitz, Michael P.; Froehlich, Alyson; Adluru, Nagesh; Wright, Brad; Ravichandran, Caitlin et al. (December 2010). "Atypical diffusion tensor hemispheric asymmetry in autism" (in en). Autism Research 3 (6): 350–358. doi:10.1002/aur.162. ISSN 1939-3792. PMID 21182212.

- ↑ Hodge, Steven M.; Makris, Nikos; Kennedy, David N.; Caviness, Verne S.; Howard, James; McGrath, Lauren; Steele, Shelly; Frazier, Jean A. et al. (March 2010). "Cerebellum, language, and cognition in autism and specific language impairment". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 40 (3): 300–316. doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0872-7. ISSN 1573-3432. PMID 19924522.

- ↑ Ameis, S. H.; Kassee, C.; Corbett-Dick, P.; Cole, L.; Dadhwal, S.; Lai, M.-C.; Veenstra-VanderWeele, J.; Correll, C. U. (November 2018). "Systematic review and guide to management of core and psychiatric symptoms in youth with autism" (in en). Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 138 (5): 379–400. doi:10.1111/acps.12918. ISSN 0001-690X. PMID 29904907. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/acps.12918.

- ↑ "Behavioral Management Therapy for Autism | NICHD - Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development" (in en). 2021-04-19. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/autism/conditioninfo/treatments/behavioral-management.

- ↑ "Learning in autism". Learning and Memory: A Comprehensive Reference. 2. Academic Press. 2008. pp. 759–72. doi:10.1016/B978-012370509-9.00152-2. ISBN 978-0-12-370504-4. http://psych.wisc.edu/lang/pdf/Dawson_AutisticLearning.pdf.

- ↑ Mayer, EA; Padua, D; Tillisch, K (October 2014). "Altered brain-gut axis in autism: comorbidity or causative mechanisms?". BioEssays 36 (10): 933–9. doi:10.1002/bies.201400075. PMID 25145752.

- ↑ 118.0 118.1 "Anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders". Clinical Psychology Review 29 (3): 216–29. April 2009. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.003. PMID 19223098.

- ↑ "Anxiety in children and adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders". Res Autism Spectr Disord 3 (1): 1–21. 2009. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2008.06.001.

- ↑ "Autism and metabolic diseases". Journal of Child Neurology 23 (3): 307–14. March 2008. doi:10.1177/0883073807308698. PMID 18079313.

- ↑ "Minor physical anomalies in autism: a meta-analysis". Molecular Psychiatry 15 (3): 300–7. March 2010. doi:10.1038/mp.2008.75. PMID 18626481.

- ↑ "What's new in autism?". European Journal of Pediatrics 167 (10): 1091–101. October 2008. doi:10.1007/s00431-008-0764-4. PMID 18597114.

- ↑ "Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 47 (8): 921–9. August 2008. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e318179964f. PMID 18645422.

- ↑ "Autism spectrum disorders and childhood-onset schizophrenia: clinical and biological contributions to a relation revisited". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 48 (1): 10–8. January 2009. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e31818b1c63. PMID 19218893.

- ↑ CDC (2023-03-23). "Key Findings from the ADDM Network". https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/addm-community-report/key-findings.html.

|

KSF

KSF