Gastrointestinal perforation

Topic: Medicine

From HandWiki - Reading time: 7 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 7 min

| Gastrointestinal perforation | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Ruptured bowel,[1] gastrointestinal rupture |

| |

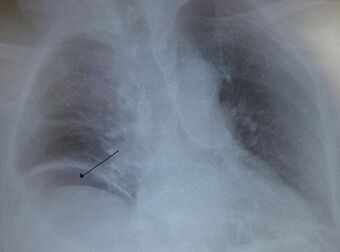

| Free air under the right diaphragm from a perforated bowel. | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology, emergency medicine |

| Symptoms | Abdominal pain, tenderness[2] |

| Complications | Sepsis, abscess[2] |

| Usual onset | Sudden or more gradual[2] |

| Causes | Trauma, following colonoscopy, bowel obstruction, colon cancer, diverticulitis, stomach ulcers, ischemic bowel, C. difficile infection[2] |

| Diagnostic method | CT scan, plain X-ray[2] |

| Treatment | Emergency surgery in the form of an exploratory laparotomy[2] |

| Medication | Intravenous fluids, antibiotics[2] |

Gastrointestinal perforation, also known as gastrointestinal rupture,[1] is a hole in the wall of the gastrointestinal tract. The gastrointestinal tract is composed of hollow digestive organs leading from the mouth to the anus.[3] Symptoms of gastrointestinal perforation commonly include severe abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting.[2] Complications include a painful inflammation of the inner lining of the abdominal wall and sepsis.

Perforation may be caused by trauma, bowel obstruction, diverticulitis, stomach ulcers, cancer, or infection.[2] A CT scan is the preferred method of diagnosis; however, free air from a perforation can often be seen on plain X-ray.[2]

Perforation anywhere along the gastrointestinal tract typically requires emergency surgery in the form of an exploratory laparotomy.[2] This is usually carried out along with intravenous fluids and antibiotics.[2] Occasionally the hole can be sewn closed while other times a bowel resection is required.[2] Even with maximum treatment the risk of death can be as high as 50%.[2] A hole from a stomach ulcer occurs in about 1 per 10,000 people per year, while one from diverticulitis occurs in about 0.4 per 10,000 people per year.[1][4]

Signs and symptoms

Gastrointestinal perforation results in sudden, severe abdominal pain at the site of perforation, which then spreads across the abdomen.[5] The pain is intensified by movement. Nausea, vomiting, hematemesis, and increased heart rate are common early symptoms. Later symptoms include fever and or chills.[6] On examination, the abdomen is rigid and tender.[1] After some time, the bowel stops moving, and the abdomen becomes silent and distended.

The symptoms of esophageal rupture may include sudden onset of chest pain.

Complications

A hole in the intestinal tracts allows intestinal contents to enter the abdominal cavity.[2] The entry of bacteria from the gastrointestinal tract into the abdomen results in peritonitis or in the formation of an abscess.[2]

Patients may develop sepsis, a life-threatening response to infection, which may appear as an increased heart rate, increased breathing rate, fever, and confusion.[2] This may progress to multi-level organ dysfunction, including acute respiratory and kidney failure.[5]

Posterior gastric wall perforation may lead to bleeding due to the involvement of gastroduodenal artery that lies behind the first part of the duodenum.[7] The death rate in this case is 20%.[7]

Causes

Gastrointestinal perforation is defined by a full-thickness injury to all layers of the gastrointestinal wall, resulting in a hole in the hollow GI tract (esophagus, stomach, small intestine, or large intestine). A hole can occur due to direct mechanical injury or progressive damage to the bowel wall due to various disease states.

Trauma or accidental perforations during medical procedures

Penetrating trauma such as from a knife or gunshot wound can puncture the bowel wall. Additionally, blunt trauma, such as in a motor vehicle accident may abruptly increase the pressure within the bowel, resulting in bowel rupture. Perforation can also be a very rare complication of certain medical procedures such as upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and colonoscopy.[8]

Infection or inflammatory disease

Appendicitis and diverticulitis are conditions in which a small, tubular area in bowel becomes inflamed and may burst.[9] A number of infections including C. difficile[10] infection can lead to full-thickness disruption of the bowel wall. In patients with inflammatory bowel disease, prolonged inflammation of the bowel wall can eventually result in perforation.

Bowel obstruction

Bowel obstruction is a blockage of the small or large intestine which prevents the normal movement of the products of digestion.[11] It may occur due to scar tissue after surgery, twisting of the bowel around itself, hernias, or gastrointestinal tumors. Reduced forward movement of bowel contents results in a build up of pressure within the part of the bowel just before the site of obstruction. This increased pressure may prevent blood flow from reaching the bowel wall, resulting in bowel ischemia (lack of blood flow), necrosis, and eventually perforation.[5]

Eating multiple magnets can also lead to perforation if the magnets attract and stick to one another through different loops of the intestine.[12]

Erosion

A peptic ulcer is a defect in the inner lining of the stomach or duodenum typically due to excessive stomach acid. Extension of the ulcer through the lining of the digestive tract results in spillage of the stomach or intestinal contents into the abdominal cavity, leading to an acute chemical peritonitis.[13][14] Helicobacter pylori infection and overuse of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs[15][16] may contribute to formation of peptic ulcers. Ingestion of corrosives[17] can lead to esophageal perforation.

Indirect causes

An often overlooked indirect cause of obstruction leading to perforation is the chronic use of opioids, which can create severe constipation and damage to the colon, often termed stercoral perforation.[18]

Diagnosis

A hole in the gastrointestinal tract causes leakage of gas into the abdominal cavity. In intestinal perforation, gas may be visible under the diaphragm on chest x-ray while the patient is in an upright position. While x-ray is a fast and inexpensive to screen for perforation, an abdominal CT scan with contrast is more sensitive and specific for establishing a diagnosis as well as determining the underlying cause.[19] Both CT and x-ray may initially appear normal, in which case diagnosis can be made by open or laparoscopic exploration of the abdomen.

White blood cells and blood lactate levels may also be elevated, particularly in the case of advanced disease including peritonitis and sepsis.[20]

Differential diagnoses of gastrointestinal perforation includes other causes of an acute abdomen, including appendicitis, diverticulitis, ruptured ovarian cyst, or pancreatitis.[21]

Treatment

Surgical intervention is nearly always required in the form of open or laparoscopic exploration. The goals of surgery are to remove any dead tissue and close the hole in the gastrointestinal wall. Peritoneal wash is performed and a drain may be placed to control any fluid collections that may form.[22] A Graham patch may be used for duodenal perforations.[23]

Conservative treatment (avoiding surgery) may be sufficient in the case of a contained perforation. It is indicated only if the person has normal vital signs and is clinically stable.[21]

Regardless of whether surgery is performed, all patients are offered pain therapy and placed on bowel rest (avoiding all food and fluids by mouth), intravenous fluids, and antibiotics.[21] A number of different antibiotics may be used such as piperacillin/tazobactam or the combination of ciprofloxacin and metronidazole.[24][25]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Domino, Frank J.; Baldor, Robert A. (2013) (in en). The 5-Minute Clinical Consult 2014. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1086. ISBN 9781451188509. https://books.google.com/books?id=2C2MAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA1086. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 Langell, JT; Mulvihill, SJ (May 2008). "Gastrointestinal perforation and the acute abdomen.". The Medical Clinics of North America 92 (3): 599–625, viii–ix. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2007.12.004. PMID 18387378.

- ↑ Langell, JT; Mulvihill, SJ (May 2008). "Gastrointestinal perforation and the acute abdomen.". The Medical Clinics of North America 92 (3): 599–625, viii–ix. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2007.12.004. PMID 18387378.

- ↑ Yeo, Charles J.; McFadden, David W.; Pemberton, John H.; Peters, Jeffrey H.; Matthews, Jeffrey B. (2012) (in en). Shackelford's Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (7 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 701. ISBN 978-1455738076. https://books.google.com/books?id=VTE-h2D1SNEC&pg=PA701.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Mayumi, Toshihiko; Yoshida, Masahiro; Tazuma, Susumu; Furukawa, Akira; Nishii, Osamu; Shigematsu, Kunihiro; Azuhata, Takeo; Itakura, Atsuo et al. (January 2016). "Practice Guidelines for Primary Care of Acute Abdomen 2015" (in en). Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Sciences 23 (1): 3–36. doi:10.1002/jhbp.303. ISSN 1868-6974. PMID 26692573.

- ↑ Ansari, Parswa. "Acute Perforation". Merck Manuals. http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/gastrointestinal-disorders/acute-abdomen-and-surgical-gastroenterology/acute-perforation.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Peptic ulcer disease". Lancet 390 (10094): 613–624. August 2017. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32404-7. PMID 28242110.

- ↑ Lohsiriwat, Varut (2010). "Colonoscopic perforation: Incidence, risk factors, management and outcome" (in en). World Journal of Gastroenterology 16 (4): 425–430. doi:10.3748/wjg.v16.i4.425. ISSN 1007-9327. PMID 20101766.

- ↑ "Definition & Facts for Appendicitis - NIDDK" (in en-US). https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/appendicitis/definition-facts.

- ↑ Langell, JT; Mulvihill, SJ (May 2008). "Gastrointestinal perforation and the acute abdomen.". The Medical Clinics of North America 92 (3): 599–625, viii–ix. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2007.12.004. PMID 18387378.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, J. Edward F. (2010-01-31), Brooks, Adam; Cotton, Bryan A.; Tai, Nigel et al., eds., "Small Bowel Obstruction" (in en), Emergency Surgery (Wiley): pp. 74–79, doi:10.1002/9781444315172.ch14, ISBN 978-1-4051-7025-3, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781444315172.ch14, retrieved 2023-11-15

- ↑ Lima, Mario (2016) (in en). Pediatric Digestive Surgery. Springer. p. 239. ISBN 9783319405254. https://books.google.com/books?id=6_mqDQAAQBAJ&pg=PA239.

- ↑ Langell, John T.; Mulvihill, Sean J. (2008-05-01). "Gastrointestinal Perforation and the Acute Abdomen". Medical Clinics of North America. Common Gastrointestinal Emergencies 92 (3): 599–625. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2007.12.004. ISSN 0025-7125. PMID 18387378. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025712507001812.

- ↑ Sigmon, David F.; Tuma, Faiz; Kamel, Bishoy G.; Cassaro, Sebastiano (2023), "Gastric Perforation", StatPearls (Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing), PMID 30137838, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519554/, retrieved 2023-11-15

- ↑ R I Russell (2001). "Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and gastrointestinal damage—problems and solutions". Postgrad Med J 77 (904): 82–88. doi:10.1136/pmj.77.904.82. PMID 11161072.

- ↑ Carlos Sostres; Carla J Gargallo; Angel Lanas (2013). "Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and upper and lower gastrointestinal mucosal damage". Arthritis Res. Ther. 15 (Suppl 3): S3. doi:10.1186/ar4175. PMID 24267289.

- ↑ Ramasamy, Kovil; Gumaste, Vivek V. (2003). "Corrosive Ingestion in Adults". Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 37 (2): 119–124. doi:10.1097/00004836-200308000-00005. PMID 12869880.

- ↑ Poitras, Renée; Warren, Daun'Lee; Oyogoa, Sylvanus (2018-01-01). "Opioid drugs and stercoral perforation of the colon: Case report and review of literature". International Journal of Surgery Case Reports 42: 94–97. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2017.11.060. ISSN 2210-2612. PMID 29232630.

- ↑ Mayumi, Toshihiko; Yoshida, Masahiro; Tazuma, Susumu; Furukawa, Akira; Nishii, Osamu; Shigematsu, Kunihiro; Azuhata, Takeo; Itakura, Atsuo et al. (January 2016). "Practice Guidelines for Primary Care of Acute Abdomen 2015" (in en). Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Sciences 23 (1): 3–36. doi:10.1002/jhbp.303. ISSN 1868-6974. PMID 26692573.

- ↑ Kruse, Ole; Grunnet, Niels; Barfod, Charlotte (December 2011). "Blood lactate as a predictor for in-hospital mortality in patients admitted acutely to hospital: a systematic review". Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine 19 (1): 74. doi:10.1186/1757-7241-19-74. ISSN 1757-7241. PMID 22202128.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Falch, C.; Vicente, D.; Häberle, H.; Kirschniak, A.; Müller, S.; Nissan, A.; Brücher, B.L.D.M. (August 2014). "Treatment of acute abdominal pain in the emergency room: A systematic review of the literature" (in en). European Journal of Pain 18 (7): 902–913. doi:10.1002/j.1532-2149.2014.00456.x. ISSN 1090-3801. PMID 24449533.

- ↑ Rustagi, T; McCarty, TR; Aslanian, HR (2015). "Endoscopic Treatment of Gastrointestinal Perforations, Leaks, and Fistulae.". Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 49 (10): 804–9. doi:10.1097/mcg.0000000000000409. PMID 26325190.

- ↑ "Gastrointestinal perforation Information | Mount Sinai - New York" (in en-US). https://www.mountsinai.org/health-library/diseases-conditions/gastrointestinal-perforation.

- ↑ Wong, PF; Gilliam, AD; Kumar, S; Shenfine, J; O'Dair, GN; Leaper, DJ (18 April 2005). "Antibiotic regimens for secondary peritonitis of gastrointestinal origin in adults.". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD004539. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004539.pub2. PMID 15846719.

- ↑ Wilson, William C.; Grande, Christopher M.; Hoyt, David B. (2007) (in en). Trauma: Resuscitation, Perioperative Management, and Critical Care. CRC Press. p. 882. ISBN 9781420015263. https://books.google.com/books?id=6FPvBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA882.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|

KSF

KSF