Head and neck cancer

Topic: Medicine

From HandWiki - Reading time: 52 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 52 min

| Head and neck cancer | |

|---|---|

| Other names | head and neck squamous cell carcinoma |

| |

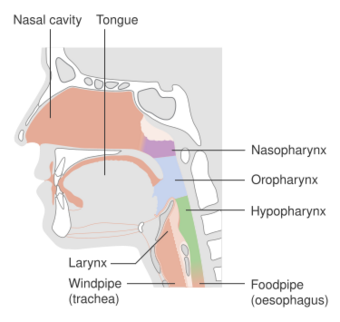

| Parts of the head and neck that can be affected by cancer | |

| Specialty | Oncology, oral and maxillofacial surgery |

| Risk factors | Alcohol, tobacco, betel quid, human papillomavirus, radiation exposure, certain workplace exposures, Epstein–Barr virus[1][2] |

| Diagnostic method | Tissue biopsy[1] |

| Prevention | Not using tobacco or alcohol[2] |

| Treatment | Surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy[1] |

| Frequency | 5.5 million (affected during 2015)[3] |

| Deaths | 379,000 (2015)[4] |

Head and neck cancer is a general term encompassing multiple cancers that can develop in the head and neck region. These include cancers of the mouth, tongue, gums and lips (oral cancer), voice box (laryngeal), throat (nasopharyngeal, oropharyngeal,[1] hypopharyngeal), salivary glands, nose and sinuses.[5]

Head and neck cancer can present a wide range of symptoms depending on where the cancer developed. These can include an ulcer in the mouth that does not heal, changes in the voice, difficulty swallowing, red or white patches in the mouth, and a neck lump.[6][7]

The majority of head and neck cancer is caused by the use of alcohol or tobacco (including smokeless tobacco). An increasing number of cases are caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV).[8][2] Other risk factors include the Epstein–Barr virus, chewing betel quid (paan), radiation exposure, poor nutrition and workplace exposure to certain toxic substances.[8] About 90% are pathologically classified as squamous cell cancers.[9][2] The diagnosis is confirmed by a tissue biopsy.[8] The degree of surrounding tissue invasion and distant spread may be determined by medical imaging and blood tests.[8]

Not using tobacco or alcohol can reduce the risk of head and neck cancer.[2] Regular dental examinations may help to identify signs before the cancer develops.[1] The HPV vaccine helps to prevent HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer.[10] Treatment may include a combination of surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy.[8] In the early stage head and neck cancers are often curable but 50% of people see their doctor when they already have an advanced disease.[11]

Globally, head and neck cancer accounts for 650,000 new cases of cancer and 330,000 deaths annually on average. In 2018, it was the seventh most common cancer worldwide, with 890,000 new cases documented and 450,000 people dying from the disease.[12] The usual age at diagnosis is between 55 and 65 years old.[13] The average 5-year survival following diagnosis in the developed world is 42–64%.[13][14]

Signs and symptoms

Head and neck cancers can cause a broad range of symptoms, many of which occur together. These can be categorised local (head and neck cancer-specific), general and gastrointestinal symptoms. Local symptoms include changes in taste and voice, inflammation of the mouth or throat (mucositis), dry mouth (xerostomia), and difficulty swallowing (dysphagia). General symptoms include difficulty sleeping, tiredness, depression, nerve damage (peripheral neuropathy). Gastrointestinal symptoms are typically nausea and vomiting.[6]

Symptoms predominantly include a sore on the face or oral cavity that does not heal, trouble swallowing, or a change in voice. In those with advanced disease, there may be unusual bleeding, facial pain, numbness or swelling, and visible lumps on the outside of the neck or oral cavity.[15] Head and neck cancer often begins with benign signs and symptoms of the disease, like an enlarged lymph node on the outside of the neck, a hoarse-sounding voice, or a progressive worsening cough or sore throat. In the case of head and neck cancer, these symptoms will be notably persistent and become chronic. There may be a lump or a sore in the throat or neck that does not heal or go away. There may be difficulty or pain in swallowing. Speaking may become difficult. There may also be a persistent earache.[16]

Mouth

Oral cancer affects the areas of the mouth, including the inner lip, tongue, floor of the mouth, gums, and hard palate. Cancers of the mouth are strongly associated with tobacco use, especially the use of chewing tobacco or dipping tobacco, as well as heavy alcohol use. Cancers of this region, particularly the tongue, are more frequently treated with surgery than other head and neck cancers. Lip and oral cavity cancers are the most commonly encountered types of head and neck cancer.[5]

- Maxillectomy (can be done with or without orbital exenteration)

- Mandibulectomy (removal of the lower jaw or part of it)

- Glossectomy (tongue removal; can be total, hemi, or partial)

- Radical neck dissection

- Combinational (e.g., glossectomy and laryngectomy done together).

Nose

Paranasal sinus and nasal cavity cancer affects the nasal cavity and the paranasal sinuses. Most of these cancers are squamous cell carcinomas.[17]

Nasopharynx

Throat

Most oropharyngeal cancers begin in the oropharynx (throat), the middle part of the throat that includes the soft palate, the base of the tongue, and the tonsils.[1] Cancers of the tonsils are more strongly associated with human papillomavirus infection than are cancers of other regions of the head and neck. HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer generally has a better outcome than HPV-negative disease, with a 54% better survival rate,[18] but this advantage for HPV-associated cancer applies only to oropharyngeal cancers.[19]

People with oropharyngeal carcinomas are at high risk of developing a second primary head and neck cancer.[20]

Hypopharynx

Larynx

Trachea and salivary glands

Cancer of the trachea is a rare cancer usually classified as a lung cancer.[21]

Most tumors of the salivary glands differ from the common head and neck cancers in cause, histopathology, clinical presentation, and therapy. Other uncommon tumors arising in the head and neck include teratomas, adenocarcinomas, adenoid cystic carcinomas, and mucoepidermoid carcinomas.[22] Rarer still are melanomas and lymphomas of the upper aerodigestive tract.

Causes

Alcohol and tobacco

Alcohol and tobacco use are major risk factors for head and neck cancer. 72% of head and neck cancer cases are caused by using both alcohol and tobacco.[23] This rises to 89% when looking specifically at laryngeal cancer.[24]

There is thought to be a dose-dependent relationship between alcohol use and development of head and neck cancer where higher rates of alcohol consumption contribute to an increased risk of developing head and neck cancer.[25][26] Alcohol use following a diagnosis of head and neck cancer also contributes to other negative outcomes. These include physical effects such as an increased risk of developing a second primary cancer or other malignancies,[27][28] cancer recurrence,[29] and worse prognosis[30] in addition to an increased chance of having a future feeding tube placed and osteoradionecrosis of the jaw. Negative social factors are also increased with sustained alcohol use after diagnosis including unemployment and work disability.[31][32]

The way in which alcohol contributes to cancer development is not fully understood. It is thought to be related to permanent damage of DNA strands by a metabolite of alcohol called acetaldehyde. Other suggested mechanisms include nutritional deficiencies and genetic variations.[31]

Tobacco smoking is one of the main risk factors for head and neck cancer. Cigarette smokers have a lifetime increased risk for head and neck cancer that is 5 to 25 times higher than the general population.[33] The ex-smoker's risk of developing head and neck cancer begins to approach the risk in the general population 15 years after smoking cessation.[34] In addition, people who smoke have a worse prognosis than those who have never smoked.[35] Furthermore, people who continue to smoke after diagnosis of head and neck cancer have the highest probability of dying compared to those who have never smoked.[36][37] This effect is seen in patients with HPV-positive head and neck cancer as well.[38][39][40] It has also been demonstrated that passive smoking, both at work and at home, increases the risk of head and neck cancer.[23]

A major carcinogenic compound in tobacco smoke is acrylonitrile.[41] Acrylonitrile appears to indirectly cause DNA damage by increasing oxidative stress, leading to increased levels of 8-oxo-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-oxo-dG) and formamidopyrimidine in DNA.[42] (see image). Both 8-oxo-dG and formamidopyrimidine are mutagenic.[43][44] DNA glycosylase NEIL1 prevents mutagenesis by 8-oxo-dG[45] and removes formamidopyrimidines from DNA.[46]

Smokeless tobacco (including products where tobacco is chewed) is a cause of oral cancer. Increased risk of oral cancer caused by smokeless tobacco is present in countries such as the United States but particularly prevalent in Southeast Asian countries where the use of smokeless tobacco is common.[5][47][48] Smokeless tobacco is associated with a higher risk of developing head and neck cancer due to the presence of the tobacco-specific carcinogen N'-nitrosonornicotine.[48]

Cigar and pipe smoking are also important risk factors for oral cancer.[49] They have a dose dependent relationship with more consumption leading to higher chances of developing cancer.[23] The use of electronic cigarettes may also lead to the development of head and neck cancers due to the substances like propylene glycol, glycerol, nitrosamines, and metals contained therein, which can cause damage to the airways.[50][5] Exposure to e-vapour has been shown to reduce cell viability and increase the rate of cell death via apoptosis or necrosis with or without nicotine.[51] This area of study requires more research, however.[50][5] Similarly, additional research is needed to understand how marijuana possibly promotes head and neck cancers.[52] A 2019 meta-analysis did not conclude that marijuana was associated with head and neck cancer risk.[53] Yet individuals with cannabis use disorder were more likely to be diagnosed with such cancers in a large study published 2024.[52]

Diet

Many dietary nutrients are associated with cancer protection and its development. Generally, foods with a protective effect with respect to oral cancer demonstrate antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects such as fruits, vegetables, curcumin and green tea. Conversely, pro-inflammatory food substances such as red meat, processed meat and fried food can increase the risk of developing head and neck cancer.[23][54] An increased adherence to the Mediterranean diet is also related to a lower risk of cancer mortality and a reduced risk of developing multiple cancers including head and neck cancer.[55] Elevated levels of nitrites in preserved meats and salted fish have been shown to increase the risk of nasopharyngeal cancer.[56][57] Overall, a poor nutritional intake (often associated with alcoholism) with subsequent vitamin deficiencies is a risk factor for head and neck cancer.[56][22]

In terms of nutritional supplements, antioxidants such as vitamin E and beta-carotene might reduce the toxic effect of radiotherapy in people with head and neck cancer but they can also increase recurrence rates, especially in smokers.[58]

Betel nut

Betel nut chewing is associated with an increased risk of head and neck cancer.[1][59] When chewed with additional tobacco in its preparation (like in gutka), there is an even higher risk, especially for oral and oropharyngeal cancers.[23]

Genetics

People who develop head and neck cancer may have a genetic predisposition for the condition. There are seven known genetic variations (loci) which specifically increase the chances of developing oral and pharyngeal cancer.[60][61] Family history, that is having a first-degree relative with head and neck cancer, is also a risk factor. In addition, genetic variations in pathways involved in alcohol metabolism (for example alcohol dehydrogenase) have been associated with an increased head and neck cancer risk.[23]

Radiation

It is known that prior exposure to radiation of the head and neck is associated with an increased risk of cancer, particularly thyroid, salivary gland and squamous cell carcinomas, although there is a time-delay of many years and the overall risk is still low.[56]

Infection

Human papillomavirus

Some head and neck cancers, and in particular oropharyngeal cancer, are caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV),[1][62] and 70% of all head and neck cancer cases are related to HPV.[62] Risk factors for HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer include multiple sexual partners, anal and oral sex and a weak immune system.[56] HPV-related head and neck cancer (throat and mouth) can affect both females and males. Increasing HPV-cancer rates in males in the United Kingdom resulted in the HPV vaccine being offered to adolescent boys between 12 and 13 (previously only offered to girls between this age due to cervical cancer risks) and men under 45 who have sex with men.[63][64]

Over 20 different high-risk HPV subtypes have been implicated in causing head and neck cancer. In particular, HPV-16 is responsible for up to 90% of oropharyngeal cancer in North America.[56] Approximately 15–25% of head and neck cancers contain genomic DNA from HPV,[65] and the association varies based on the site of the tumor.[66] In the case of HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer, the highest distribution is in the tonsils, where HPV DNA is found in 45–67% of the cases,[67] and it is less often in the hypopharynx (13–25%), and least often in the oral cavity (12–18%) and larynx (3–7%).[68][69]

Positive HPV16 status is associated with an improved prognosis over HPV-negative oropharyngeal cancer due to better response to radiotherapy and chemotherapy.[70]

HPV can induce tumors by several mechanisms:[70][71]

- E6 and E7 oncogenic proteins.

- Disruption of tumor suppressor genes.

- High-level DNA amplifications, for example, oncogenes.

- Generating alternative nonfunctional transcripts.

- Interchromosomal rearrangements.

- Distinct host genome methylation and expression patterns, produced even when the virus is not integrated into the host genome.

There are observed biological differences between HPV-positive and HPV-negative head and neck cancer, for example in terms of mutation patterns. In HPV-negative disease, genes frequently mutated include TP53, CDKN2A and PIK3CA.[72] In HPV-positive disease, these genes are less frequently mutated, and the tumour suppressor gene p53 and pRb (protein retinoblastoma) are commonly inactivated by HPV oncoproteins E6 and E7 respectively.[73] In addition, viral infections such as HPV can cause aberrant DNA methylation during cancer development. HPV-positive head and neck cancers demonstrate higher levels of such DNA methylation compared to HPV-negative disease.[74]

E6 sequesters p53 to promote p53 degradation, while E7 inhibits pRb. Degradation of p53 results in cells being unable to respond to checkpoint signals that are normally present to activate apoptosis when DNA damage is signalled. Loss of pRb leads to deregulation of cell proliferation and apoptosis. Both mechanisms therefore leave cell proliferation unchecked and increase the chance of carcinogenesis.[75]

Epstein–Barr virus

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection is associated with nasopharyngeal cancer. Nasopharyngeal cancer caused by EBV commonly occurs in some countries of the Mediterranean and Asia, where EBV antibody titers can be measured to screen high-risk populations.[76][77]

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

People after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) are at a higher risk for oral cancer. Post-HSCT oral cancer may have more aggressive behavior and a poorer prognosis when compared to oral cancer in non-HSCT patients.[78] This effect is supposed to be due to continuous, lifelong immune suppression and chronic oral graft-versus-host disease.[78]

Other risk factors

Several other risk factors have been identified in the development of head and neck cancer. These include occupational environmental carcinogen exposure such as asbestos, wood dust, mineral acid, sulfuric acid mists and metal dusts. In addition, weakened immune systems, age greater than 55 years, poor socioeconomic factors such as lower incomes and occupational status, and low body mass index (<18.5 kg/m2) are also risk factors.[56][79][23] Poor oral hygiene and chronic oral cavity inflammation (for example secondary to chronic gum inflammation) are also linked to an increased head and neck cancer risk.[80][81] The presence of leukoplakia, which is the appearance of white patches or spots in the mouth, can develop into cancer in about 1⁄3 of cases.[22]

Diagnosis

A significant proportion of people with head and neck cancer will present to their physicians with an already advanced stage disease.[11] This can either be down to patient factors (delays in seeking medical attention), or physician factors (such as delays in referral from primary care, or non-diagnostic investigation results).[82]

A person usually presents to the physician complaining of one or more of the typical symptoms. These symptoms may be site specific (such as a laryngeal cancer causing hoarse voice), or not site specific (earache can be caused by multiple types of head and neck cancers).[6]

The physician will undertake a thorough history to determine the nature of the symptoms and the presence or absence of any risk factors. The physician will also ask about other illnesses such as heart or lung diseases as they may impact their fitness for potentially curative treatment. Clinical examination will involve examination of the neck for any masses, examining inside the mouth for any abnormalities and assessing the rest of the pharynx and larynx with a nasendoscope.[83]

Neck masses typically undergo assessment with ultrasound and a fine-needle aspiration (FNA, a type of needle biopsy). Concerning lesions that are readily accessible (such as in the mouth) can be biopsied with a local anaesthetic. Lesions less readily available can be biopsied either with the patient awake or under a general anaesthetic depending on local expertise and availability of specialist equipment.[84]

The cancer will also need to be staged (accurately determine its size, association with nearby structures, and spread to distant sites). This is typically done by scanning the patient with a combination of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT) and/or positron emission tomography (PET). Exactly which investigations are required will depend on a variety of factors such as the site of concern and the size of the tumour.[85]

Some people will present with a neck lump containing cancer cells (identified by FNA) that have spread from elsewhere, but with no identifiable primary site on initial assessment. In such cases people will undergo additional testing to attempt to find the initial site of cancer, as this has significant implications for their treatment. These patients undergo MRI scanning, PET-CT and then panendoscopy and biopsies of any abnormal areas. If the scans and panendoscopy still do not identify a primary site for the cancer, affected people will undergo a bilateral tonsillectomy and tongue base mucosectomy (as these are the most common subsites of cancer that spread to the neck). This procedure can be done with or without robotic assistance.[86]

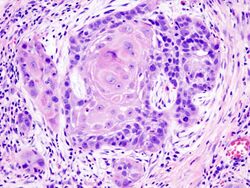

Once a diagnosis is confirmed, a multidisciplinary discussion of the optimal treatment strategy will be undertaken between the radiation oncologist, surgical oncologist, and medical oncologist. A histopathologist and a radiologist will also be present to discuss the biopsy and imaging findings.[85] Most (90%) cancers of the head and neck are squamous cell-derived, termed "head-and-neck squamous-cell carcinomas".[9]

Histopathology

Throat cancers are classified according to their histology or cell structure and are commonly referred to by their location in the oral cavity and neck. This is because where the cancer appears in the throat affects the prognosis; some throat cancers are more aggressive than others, depending on their location. The stage at which the cancer is diagnosed is also a critical factor in the prognosis of throat cancer. Treatment guidelines recommend routine testing for the presence of HPV for all oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma tumors.[87] Accurate prognostic stratification as well as segmentation of Head-and-Neck Squamous-Cell-Carcinoma (HNSCC) patients can be an important clinical reference when designing therapeutic strategies. Study [88] developed a deep learning framework combining PET/CT fusion imaging with Hybrid Machine Learning Systems (HMLS) for automated tumor segmentation and recurrence-free survival prediction in HNSCC patients. They set to enable automated segmentation of tumors and prediction of recurrence-free survival (RFS) using advanced deep learning techniques and Hybrid Machine Learning Systems (HMLSs).

Squamous-cell carcinoma

All squamous cell carcinomas arising from the oropharynx, and all neck node metastases of unknown primary should undergo testing for HPV status. This is essential to adequately stage the tumour and adequately plan treatment. Due to the different biology of HPV positive and negative cancers, differentiating HPV status is also important for ongoing research to determine the best treatments.[89]

Nasopharyngeal carcinomas, or neck node metastases possibly arising from the nasopharynx will also be tested for Ebstein Barr virus.[90]

The tumor marker Cyfra 21-1 may be useful in diagnosing squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN).[91]

Adenocarcinoma

Adenocarcinoma is a cancer of the epithelial tissue that has glandular characteristics. Several head and neck cancers are adenocarcinomas (either of intestinal or non-intestinal cell types).[92]

Prevention

Avoidance of risk factors (such as smoking and alcohol) is the single most effective form of prevention.[56]

Regular dental examinations may identify pre-cancerous lesions in the oral cavity.[1] While screening in the general population does not appear to be useful, screening high-risk groups by examination of the throat might be useful.[2] Head and neck cancer is often curable if it is diagnosed early; however, outcomes are typically poor if it is diagnosed late.[2]

When diagnosed early, oral, head, and neck cancers can be treated more easily, and the chances of survival increase tremendously.[1] The HPV vaccine helps to prevent the development of HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer.[10]

Management

Improvements in diagnosis and local management, as well as targeted therapy, have led to improvements in quality of life and survival for people with head and neck cancer.[93]

After a histologic diagnosis has been established and tumor extent determined, such as with the use of PET-CT,[94] the selection of appropriate treatment for a specific cancer depends on a complex array of variables, including tumor site, relative morbidity of various treatment options, concomitant health problems, social and logistic factors, previous primary tumors, and the person's preference. Treatment planning generally requires a multidisciplinary approach involving specialist surgeons, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists.

Surgery

Surgery as a treatment is frequently used for most types of head and neck cancer. Usually, the goal is to remove the cancerous cells entirely. This can be particularly tricky if the cancer is near the larynx and can result in the person being unable to speak. Surgery is also commonly used to resect (remove) some or all of the cervical lymph nodes to prevent further spread of the disease. Transoral robotic surgery (TORS) is gaining popularity worldwide as the technology and training become more accessible. It now has an established role in the treatment of early stage oropharyngeal cancer.[95] There is also a growing trend worldwide towards TORS for the surgical treatment of laryngeal and hypopharyngeal tumours.[96][97]

CO2 laser surgery is also another form of treatment. Transoral laser microsurgery allows surgeons to remove tumors from the voice box with no external incisions. It also allows access to tumors that are not reachable with robotic surgery. During the surgery, the surgeon and pathologist work together to assess the adequacy of excision ("margin status"), minimizing the amount of normal tissue removed or damaged.[98] This technique helps give the person as much speech and swallowing function as possible after surgery.[99]

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is the most common form of treatment. There are different forms of radiation therapy, including 3D conformal radiation therapy, intensity-modulated radiation therapy, particle beam therapy, and brachytherapy, which are commonly used in the treatment of cancers of the head and neck. Most people with head and neck cancer who are treated in the United States and Europe are treated with intensity-modulated radiation therapy using high-energy photons. At higher doses, head and neck radiation is associated with thyroid dysfunction and pituitary axis dysfunction.[100] Radiation therapy for head and neck cancers can also cause acute skin reactions of varying severity, which can be treated and managed with topically applied creams or specialist films.[101]

Chemotherapy

Docetaxel-based chemotherapy has shown a very good response in locally advanced head and neck cancer. Docetaxel is the only taxane approved by the FDA for head and neck cancer, in combination with cisplatin and fluorouracil for the induction treatment of inoperable, locally advanced head and neck cancer.[102]

There is no evidence that erythropoietin should be routinely given with radiotherapy.[103]

Photodynamic therapy

Photodynamic therapy may have promise for treating mucosal dysplasia and small head and neck tumors.[22] Amphinex is showing good results in early clinical trials for the treatment of advanced head and neck cancer.[104]

Targeted therapy

Cetuximab is used for treating people with advanced-stage cancer who cannot be treated with conventional chemotherapy (cisplatin).[105][106] However, cetuximab's efficacy is still under investigation by researchers.[107]

Gendicine is a gene therapy that employs an adenovirus to deliver the tumor suppressor gene p53 to cells. It was approved in China in 2003 for the treatment of head and neck cancer.[108]

The mutational profiles of HPV+ and HPV- head and neck cancer have been reported, further demonstrating that they are fundamentally distinct diseases. [109][non-primary source needed]

Immunotherapy

In 2016, the FDA granted accelerated approval to pembrolizumab for the treatment of people with recurrent or metastatic head and neck cancer with disease progression on or after platinum-containing chemotherapy.[110] Later that year, the FDA approved nivolumab for the treatment of recurrent or metastatic head and neck cancer with disease progression on or after platinum-based chemotherapy.[111] In 2019, the FDA approved pembrolizumab for the first-line treatment of metastatic or unresectable recurrent head and neck cancer.[112]

Treatment side effects

Depending on the treatment used, people with head and neck cancer may experience various symptoms and treatment side effects depending on the type and site of the treatment used.[113][22]

Difficulties with eating and drinking

Even before treatment, tumours themselves may interfere with a person's ability to eat and drink normally[114][115] and these may be among the early presenting symptoms.[7] Some treatments can also lead to difficulty with eating and drinking (dysphagia).[115][116] This might lead to feelings of food sticking in the throat, food and drink going down the wrong way (aspiration),[117] taking a long time to chew and swallow food, a change in taste or appetite, and overall changes in enjoyment of eating and drinking.[118][119]

Surgery results in changes to anatomy, altering the function and coordination of key structures involved in eating and drinking. Surgery can also result in damage or bruising to nerves needed to move and provide sensation to the muscles involved in swallowing. Following surgery, a person may experience difficulties with chewing, swallowing and jaw opening. Pain, and oedema can be present after surgery, particularly in the early postoperative period.[120] The severity of swallowing issues after surgery depends on the location of the tumour and the volume of tissue removed. Factors such as age, other pre-existing illnesses (comorbidity) and having any earlier problems with swallowing will also impact swallow outcomes. Transoral surgical techniques remove tumours with minimal disruption to normal tissue. This is an established technique in the management of oropharyngeal cancer, with the aim to improve long-term swallow outcomes. However, difficulties with swallowing are common in the early period following the surgery.[120] Surgery may involve substituting some anatomy with tissue from other areas of the body (soft tissue or bone flap reconstruction). This can lead to changes in sensation and function of this new tissue.[121]

Radiotherapy can lead to inflammation of the mouth or throat (mucositis), dry mouth (xerostomia),[22] reduced motion of the jaw (trismus),[122] osteoradionecrosis,[22] changes to dentition, fatigue, oedema fibrosis,[123][124] atrophy.[101] These changes can impair the movement of key swallowing structures but their severity depends on the dose and site of the radiotherapy.[125][126][127] Recent advancements in the way radiotherapy is planned and delivered aim to reduce some of these side effects.[128][129]

Communication

Speech may become slurred, hard to understand, or the voice may become hoarse or weak. The impact on communication depends on the site and size of the tumour and the treatments used. The tumour itself may result in changes to the voice, which may be among one of the presenting signs and symptoms.[7]

Surgery can lead to changes in the shape and size of the oral structures (tongue, lips, palate, dental extractions) which can impact on how they move to produce speech sounds.[130]

Surgery may result in changes to anatomy or neurology such as removal of a structure or damage to nerves. For example, removal of the larynx (voice box) in a total laryngectomy or damage to the vagus nerve during tumour removal leading to vocal fold paresis or palsy.[131]

If surgery affects the upper jaw bone, then this can also affect the development and resonance of speech sounds, resulting in hypernasal speech and difficulty in making certain sounds that are dependent on the velopharyngeal competence. Dental and speech prosthetics can sometimes be provided to compensate for these changes, however there is no effective means to restore normal (pre-surgical) speech sounds.[132][133]

Head and neck cancer treatments can lead to changes in the sound of the voice. The impact of surgery on the voice can depend on the size of the resection and subsequent amount of scarring on the vocal folds.[134] Radiotherapy treatment may improve the voice or worsen it, depending on pre-treatment voice function, and the site and dose treatment. This may be short- or long-term depending on the treatment plan.[135]

Upper airway

People may experience changes to their breathing from the tumour itself or from side-effects of head and neck cancer treatments. Both surgery and radiotherapy can cause changes in breathing in either the short- or long-term e.g. through a tracheostomy tube or stoma in the neck (laryngectomy). The extent of these changes is often dependent on a range of factors including type of surgery, position of the tumour and the individual's tissue response to radiotherapy.[136]

Shoulder dysfunction

Surgical neck dissection is the most common component of treatment in both new cancers and in cancers previously treated but with residual neck disease. Shoulder dysfunction is by far the most common side effect after neck dissection.[137][138] Its symptoms can include shoulder pain, decreased range of motion, and muscle loss.[139] The prevalence of shoulder dysfunction varies based on the type of neck dissection and the diagnostic tools used, but it can occur in as many as 50 to 100% of cases.[137][138] Over 30% of people still experience shoulder pain and reduced function 12 months after surgery.[140] Problems with shoulder and neck movement can reduce people's abilities to return to work, and nearly half of people with shoulder disability cease working.[138]

Treatment for shoulder dysfunction, whether pain, weakness or functional difficulties, is commonly provided through physiotherapy. Physiotherapists assess the specific symptoms and then prescribe treatments which are often exercise-based, tailored to individual problems[141][140]

Nutrition and hydration

People may find it hard to eat and drink enough due to the side effects of treatments. These may be associated with chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgery. This can increase their risk of malnutrition. People with head and neck cancer need to be screened for malnutrition risk on diagnosis and regularly throughout their treatment and referred to a dietitian.[85] Dietary counselling or oral nutritional supplements may be required to treat and manage any malnutrition.[142] Some people might be recommended to have enteral feeding, a method that adds nutrients directly into a person's stomach using a nasogastric feeding tube or a gastrostomy tube.[143][144] The type of tube used and when it is placed is decided on a case-by-case basis with guidance from the treating team.[145] However, for people undergoing radiotherapy or chemotherapy, it is not yet known what the most effective method and timing of enteral feeding is for staying nourished during treatment.[146][147]

Chemotherapy can lead to taste changes, nausea and vomiting. It can deprive the body of vital fluids (although these may be obtained intravenously if necessary). Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting can lead to impaired kidney function, electrolyte disturbances, dehydration, malnutrition and gastrointestinal trauma.[148] It also causes significant psychological distress.[149]

Rehabilitation and long-term care

Oral rehabilitation

Oral health, dental pain, chewing and swallowing ability remain common long-term concerns of people who have undergone treatment for head and neck cancer, particularly those who have received radiotherapy to the salivary glands and oral structures.[150][151]

People are at increased risk of long-term xerostomia (dry mouth), thicker saliva, dental pain, dental diseases, and osteoradionecrosis following head and neck cancer treatment involving radiotherapy. Long-term care necessitates adherence to preventative oral hygiene protocols including high fluoride toothpastes, fluoride varnish, and more frequent dental examinations.[152][153]

The oral rehabilitation process can vary significantly. In some cases it is possible to provide individuals with dental prostheses within weeks, however this can also take several years.[154][155][156]

It is important that all people with head and neck cancer receive a specialist dental assessment (restorative dentistry) prior to the start of treatment, particularly if radiotherapy is planned. The purpose of this assessment is to facilitate an improvement in oral health prior to the start of cancer therapies and thus minimise the risk of long-term side effects such as osteoradionecrosis.[157]

Speech, voice and swallow function

Rehabilitation targeting changes to speech, voice and swallowing aims to optimise function and help manage long-term effects.[115][158] Rehabilitation can consist of therapy exercises and compensation strategies. Therapy exercises may involve muscle strengthening exercises e.g. for the tongue or larynx (voice box), while compensation strategies can involve texture modification or changes to head postures when swallowing. Swallowing rehabilitation may integrate several therapies using training devices, proactive therapies and intensive bootcamp programmes.[159][160][122][161]

Early intervention promoting mobilisation of the swallowing muscles is likely to improve effectiveness.[162][163][164]

Radiation-induced side effects

Radiotherapy can cause delayed tissue fibrosis,[165] lower cranial neuropathy[166] and osteoradionecrosis of bones included in the fields of radiation. These late changes affect the functions of swallowing, speech, voice, breathing and mouth-opening (trismus) often necessitating placement of a feeding tube and/or tracheostomy. Symptoms usually present gradually, years after treatment though there is no agreed definition.

Several risk factors have been identified (e.g. tumour site,[167][168] gender,[169] tumour stage), but the evidence base is conflicting. Reducing the radiotherapy dose to structures critical to swallowing function may improve function in the longer-term.[170] Treatment options for late radiation-associated dysphagia are limited.[171] Some, more severely affected patients, choose to undergo a functional laryngectomy which can improve how they feel about swallowing and communication[172] and can facilitate tracheosophageal speech and removal of feeding tubes though outcomes are variable.

Psychosocial

Programs to support the emotional and social well-being of people who have been diagnosed with head and neck cancer may be offered.[173] There is no clear evidence on the effectiveness of these interventions or any particular type of psychosocial program or length of time that is most helpful for those with head and neck cancer.[173]

Prognosis

Although early-stage head and neck cancers (especially laryngeal and oral cavity) have high cure rates, up to 50% of people with head and neck cancer present with advanced disease.[174] Cure rates decrease in locally advanced cases, whose probability of cure is inversely related to tumor size and even more so to the extent of regional node involvement. HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer has been shown to respond better to chemoradiation and, subsequently, have a better prognosis compared to non-associated HPV head and neck cancer.[12]

Consensus panels in America (AJCC) and Europe (UICC) have established staging systems for head and neck cancers. These staging systems attempt to standardize clinical trial criteria for research studies and define prognostic categories of disease. Head and neck cancers are staged according to the TNM classification system, where T is the size and configuration of the tumor, N is the presence or absence of lymph node metastases, and M is the presence or absence of distant metastases. The T, N, and M characteristics are combined to produce a "stage" of the cancer, from I to IVB.[175]

Disease recurrence

Despite ongoing advances in the treatment of primary disease, recurrence rates remain high. Regardless of site of disease, the overall recurrence rate for advanced stage head and neck cancer is up to 50%.[176][177] For recurrent oropharyngeal cancer, recurrence rates in the original site of the disease vary from 9% for HPV-positive disease to 26% for HPV- negative disease.[178]

Treatments for recurrent disease include potentially curative surgery either open or transoral robotic or re-irradiation which can be associated with significant changes to speech and swallowing function.[179][180][181] Non curative treatment options include immunotherapy,[182] chemotherapy, and other emerging therapies undergoing scientific investigation.[183] Treatment decision making in recurrent head and neck cancer is often challenging.[184] Careful pre-treatment counselling and an evaluation of the individual's values and goals should be at the centre of the treatment decision-making.[185]

Mental health

Cancer in the head or neck may impact a person's mental well-being and can sometimes lead to social isolation.[173] This largely results from a decreased ability or inability to eat, speak, or effectively communicate. Physical appearance is often altered by the cancer itself and/or as a consequence of treatment side effects. Psychological distress may occur, and feelings such as uncertainty and fear may arise.[173] Some people may also have a changed physical appearance, differences in swallowing or breathing, and residual pain to manage.[173]

Caregiver stress

Caregivers for people with head and neck cancer show higher rates of caregiver stress and poorer mental health compared to both the general population and those caring for people with different diseases.[186] Caregivers show increased rates of depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder and physical health decline.[187] Caregivers frequently report loss associated with their caring role, including loss of role, certainty, security, finances, intimacy and enjoyment from social activities.[188]

The high symptom burden patients' experience necessitates complex caregiver roles, often requiring hospital staff training, which caregivers can find distressing when asked to do so for the first time. It is becoming increasingly apparent that caregivers (most often spouses, children, or close family members) might not be adequately informed about, prepared for, or trained for the tasks and roles they will encounter during the treatment and recovery phases of this unique patient population, which span both technical and emotional support.[189] Examples of technically difficult caregiver duties include tube feeding, oral suctioning, wound maintenance, medication delivery safe for tube feeding, and troubleshooting home medical equipment. If the cancer affects the mouth or larynx, caregivers must also find a way to effectively communicate among themselves and with their healthcare team. This is in addition to providing emotional support for the person undergoing cancer therapy.[189]

Of note, caregivers who report lower quality of life demonstrate increased burden and fatigue that extend beyond the treatment phase. Factors promoting coping and resilience among caregivers include access to information and support, supportive mechanisms to aid transition from treatment to recovery and personal attributes such as optimism and perspective.[188]

Fear of recurrence

Fear of recurrence can occur in up to 72% of cancer survivors in general.[190] Fear of recurrence can remain with head and neck cancer survivors in the long-term, and it has been highlighted as a frequently reported unmet need and a potential cause for high levels of anxiety.[191][192]

Emotional distress

People with head and neck cancer are at increased risk of emotional distress. Around a fifth of people report symptoms of depression, anxiety, or post-traumatic stress, and more than a third report general emotional distress or insomnia symptoms. People undergoing primary chemoradiotherapy experience significantly higher anxiety than those undergoing surgery, and people who smoke or have an advanced stage of tumour experience increased distress.[193]

Out of 100,000 individuals with head and neck cancer, around 160 commit suicide per year.[193]

Those who have depression or depressive symptoms before the start of their treatment might have worse rates of overall survival.[194]

Others

Epidemiology

Globally, head and neck cancer accounts for 650,000 new cases of cancer and 330,000 deaths annually on average. In 2018, it was the seventh most common cancer worldwide, with 890,000 new cases documented and 450,000 people dying from the disease.[12] The risk of developing head and neck cancer increases with age, especially after 50 years. Most people who do so are between 50 and 70 years old.[22]

In North America and Europe, the tumors usually arise from the oral cavity, oropharynx, or larynx, whereas nasopharyngeal cancer is more common in the Mediterranean countries and in the Far East. In Southeast China and Taiwan, head and neck cancer, specifically nasopharyngeal cancer, is the most common cause of death in young men.[196]

United States

In the United States, head and neck cancer makes up 3% of all cancer cases (averaging 53,000 new diagnoses per year) and 1.5% of cancer deaths.[197] The 2017 worldwide figure cites head and neck cancers as representing 5.3% of all cancers (not including non-melanoma skin cancers).[198][5]

Head and neck cancer secondary to chronic alcohol or tobacco use has been steadily declining as less of the population chronically smokes tobacco.[12]

HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer is rising, particularly in younger people in westernized nations, which is thought to be reflective of changes in oral sexual practices, specifically with regard to the number of oral sexual partners.[5][12] This increase since the 1970s has mostly affected wealthier nations and male populations.[199][200][5] This is due to evidence suggesting that transmission rates of HPV from women to men are higher than from men to women, as women often have a higher immune response to infection.[5][201] In the United States, the incidence of HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer has overtaken HPV-positive cervical cancer as the leading HPV related cancer type.[202]

- In 2008, there were 22,900 cases of oral cavity cancer, 12,250 cases of laryngeal cancer, and 12,410 cases of pharyngeal cancer in the United States.[22]

- In 2002, 7,400 Americans were projected to die of these cancers.[203]

- More than 70% of throat cancers are at an advanced stage when discovered.[204]

- Men are 89% more likely than women to be diagnosed with these cancers and are almost twice as likely to die of them.[203]

- African Americans are disproportionately affected by head and neck cancer, with younger ages of incidence, increased mortality, and more advanced disease at presentation.[174] Laryngeal cancer incidence is higher in African Americans relative to white, Asian, and Hispanic populations. There is a lower survival rate for similar tumor states in African Americans with head and neck cancer.[22]

Research

Immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors is being investigated in head and neck cancers.[205]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 "Oropharyngeal Cancer Treatment (Adult) (PDQ®)–Patient Version" (in en). National Cancer Institute. 22 November 2019. https://www.cancer.gov/types/head-and-neck/patient/adult/oropharyngeal-treatment-pdq.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 5.8. ISBN 978-92-832-0429-9.

- ↑ "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet 388 (10053): 1545–1602. October 2016. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMID 27733282.

- ↑ "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet 388 (10053): 1459–1544. October 2016. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMID 27733281.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 "Epidemiology of head and neck cancers: an update". Current Opinion in Oncology 32 (3): 178–186. May 2020. doi:10.1097/CCO.0000000000000629. PMID 32209823.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Mathew, Asha; Tirkey, Amit Jiwan; Li, Hongjin; Steffen, Alana; Lockwood, Mark B.; Patil, Crystal L.; Doorenbos, Ardith Z. (2 October 2021). "Symptom Clusters in Head and Neck Cancer: A Systematic Review and Conceptual Model" (in en). Seminars in Oncology Nursing 37 (5). doi:10.1016/j.soncn.2021.151215. PMID 34483015.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Bradley, Paula T.; Lee, Ying Ki; Albutt, Abigail; Hardman, John; Kellar, Ian; Odo, Chinasa; Randell, Rebecca; Rousseau, Nikki et al. (2024-06-17). "Nomenclature of the symptoms of head and neck cancer: a systematic scoping review". Frontiers in Oncology 14. doi:10.3389/fonc.2024.1404860. ISSN 2234-943X. PMID 38952557.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 "Head and Neck Cancers". NCI. 29 March 2017. https://www.cancer.gov/types/head-and-neck/head-neck-fact-sheet.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Epidemiologic trends in head and neck cancer and aids in diagnosis". Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America 26 (2): 123–141. May 2014. doi:10.1016/j.coms.2014.01.001. PMID 24794262.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Macilwraith, Philip; Malsem, Eve; Dushyanthen, Sathana (2023-04-24). "The effectiveness of HPV vaccination on the incidence of oropharyngeal cancers in men: a review" (in en). Infectious Agents and Cancer 18 (1): 24. doi:10.1186/s13027-022-00479-3. ISSN 1750-9378. PMID 37095546.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Johnson, Daniel E.; Burtness, Barbara; Leemans, C. René; Lui, Vivian Wai Yan; Bauman, Julie E.; Grandis, Jennifer R. (2020-11-26). "Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma" (in en). Nature Reviews Disease Primers 6 (1): 92. doi:10.1038/s41572-020-00224-3. ISSN 2056-676X. PMID 33243986.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 "Head and Neck Cancer". The New England Journal of Medicine 382 (1): 60–72. January 2020. doi:10.1056/nejmra1715715. PMID 31893516.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Oral Cavity and Pharynx Cancer". April 2016. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/oralcav.html.

- ↑ (in en) Radiation Therapy for Head and Neck Cancers: A Case-Based Review. Springer. 2014. p. 18. ISBN 978-3-319-10413-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=zcGPBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA18.

- ↑ "Initial symptoms in patients with HPV-positive and HPV-negative oropharyngeal cancer". JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 140 (5): 441–447. May 2014. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2014.141. PMID 24652023.

- ↑ Head and neck cancer: emerging perspectives. Amsterdam: Academic Press. 2003. ISBN 978-0-08-053384-1. OCLC 180905431.

- ↑ "Paranasal Sinus and Nasal Cavity Cancer Treatment (Adult) (PDQ®)–Patient Version" (in en). National Cancer Institute. 8 November 2019. https://www.cancer.gov/types/head-and-neck/patient/adult/paranasal-sinus-treatment-pdq.

- ↑ "Human papillomavirus related head and neck cancer survival: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Oral Oncology 48 (12): 1191–1201. December 2012. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.06.019. PMID 22841677. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237088860.

- ↑ "Survival of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck in relation to human papillomavirus infection: review and meta-analysis". International Journal of Cancer 121 (8): 1813–1820. October 2007. doi:10.1002/ijc.22851. PMID 17546592.

- ↑ "Synchronous primary cancers of the head and neck region and upper aero digestive tract: defining high-risk patients". Indian Journal of Cancer 50 (4): 322–326. 2013. doi:10.4103/0019-509x.123610. PMID 24369209.

- ↑ "Throat cancer | Head and neck cancers". Cancer Research UK. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/head-neck-cancer/throat.

- ↑ 22.00 22.01 22.02 22.03 22.04 22.05 22.06 22.07 22.08 22.09 "Head and neck tumors.". Cancer management: a multidisciplinary approach. (11th ed.). Cmp United Business Media. 2008. pp. 39–86. ISBN 978-1-891483-62-2. http://thymic.org/uploads/reference_sub/04headneck.pdf.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 23.6 Gormley, Mark; Creaney, Grant; Schache, Andrew; Ingarfield, Kate; Conway, David I. (2022-11-11). "Reviewing the epidemiology of head and neck cancer: definitions, trends and risk factors" (in en). British Dental Journal 233 (9): 780–786. doi:10.1038/s41415-022-5166-x. ISSN 0007-0610. PMID 36369568.

- ↑ Hashibe, Mia; Brennan, Paul; Chuang, Shu-chun; Boccia, Stefania; Castellsague, Xavier; Chen, Chu; Curado, Maria Paula; Dal Maso, Luigino et al. (2009-02-01). "Interaction between Tobacco and Alcohol Use and the Risk of Head and Neck Cancer: Pooled Analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium" (in en). Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 18 (2): 541–550. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0347. ISSN 1055-9965. PMID 19190158.

- ↑ Tramacere, Irene; Negri, Eva; Bagnardi, Vincenzo; Garavello, Werner; Rota, Matteo; Scotti, Lorenza; Islami, Farhad; Corrao, Giovanni et al. (4 May 2010). "A meta-analysis of alcohol drinking and oral and pharyngeal cancers. Part 1: Overall results and dose-risk relation" (in en). Oral Oncology 46 (7): 497–503. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.03.024. PMID 20444641. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1368837510001363.

- ↑ Bagnardi, V; Rota, M; Botteri, E; Tramacere, I; Islami, F; Fedirko, V; Scotti, L; Jenab, M et al. (25 November 2014). "Alcohol consumption and site-specific cancer risk: a comprehensive dose–response meta-analysis" (in en). British Journal of Cancer 112 (3): 580–593. doi:10.1038/bjc.2014.579. ISSN 0007-0920. PMID 25422909.

- ↑ Leoncini, Emanuele; Vukovic, Vladimir; Cadoni, Gabriella; Giraldi, Luca; Pastorino, Roberta; Arzani, Dario; Petrelli, Livia; Wünsch-Filho, Victor et al. (19 May 2018). "Tumour stage and gender predict recurrence and second primary malignancies in head and neck cancer: a multicentre study within the INHANCE consortium" (in en). European Journal of Epidemiology 33 (12): 1205–1218. doi:10.1007/s10654-018-0409-5. ISSN 0393-2990. PMID 29779202.

- ↑ Chuang, Shu-Chun; Scelo, Ghislaine; Tonita, Jon M.; Tamaro, Sharon; Jonasson, Jon G.; Kliewer, Erich V.; Hemminki, Kari; Weiderpass, Elisabete et al. (2008-11-15). "Risk of second primary cancer among patients with head and neck cancers: A pooled analysis of 13 cancer registries" (in en). International Journal of Cancer 123 (10): 2390–2396. doi:10.1002/ijc.23798. ISSN 0020-7136. PMID 18729183. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ijc.23798.

- ↑ Cadoni, G.; Giraldi, L.; Petrelli, L.; Pandolfini, M.; Giuliani, M.; Paludetti, G.; Pastorino, R.; Leoncini, E. et al. (December 2017). "Prognostic factors in head and neck cancer: a 10-year retrospective analysis in a single-institution in Italy". Acta Otorhinolaryngologica Italica 37 (6): 458–466. doi:10.14639/0392-100X-1246. ISSN 0392-100X. PMID 28663597. PMC 5782422. http://www.actaitalica.it/issues/2017/6-2017/03_CADONI.pdf.

- ↑ Sawabe, Michi; Ito, Hidemi; Oze, Isao; Hosono, Satoyo; Kawakita, Daisuke; Tanaka, Hideo; Hasegawa, Yasuhisa; Murakami, Shingo et al. (2017-01-26). "Heterogeneous impact of alcohol consumption according to treatment method on survival in head and neck cancer: A prospective study" (in en). Cancer Science 108 (1): 91–100. doi:10.1111/cas.13115. ISSN 1347-9032. PMID 27801961.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Marziliano, Allison; Teckie, Sewit; Diefenbach, Michael A. (27 November 2019). "Alcohol-related head and neck cancer: Summary of the literature". Head & Neck 42 (4): 732–738. doi:10.1002/hed.26023. ISSN 1097-0347. PMID 31777131.

- ↑ Simcock, R.; Simo, R. (2016-04-16). "Follow-up and Survivorship in Head and Neck Cancer" (in en). Clinical Oncology 28 (7): 451–458. doi:10.1016/j.clon.2016.03.004. PMID 27094976. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0936655516300061.

- ↑ "Role of alcohol and tobacco in the aetiology of head and neck cancer: a case-control study in the Doubs region of France". European Journal of Cancer, Part B 31B (5): 301–309. September 1995. doi:10.1016/0964-1955(95)00041-0. PMID 8704646.

- ↑ "Time since stopping smoking and the risk of oral and pharyngeal cancers". Journal of the National Cancer Institute 91 (8): 726–728. April 1999. doi:10.1093/jnci/91.8.726a. PMID 10218516.

- ↑ Fortin, André; Wang, Chang Shu; Vigneault, Éric (2008-11-25). "Influence of Smoking and Alcohol Drinking Behaviors on Treatment Outcomes of Patients With Squamous Cell Carcinomas of the Head and Neck" (in en). International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics 74 (4): 1062–1069. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.09.021. PMID 19036528. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0360301608034998.

- ↑ Merlano, Marco Carlo; Denaro, Nerina; Galizia, Danilo; Abbona, Andrea; Paccagnella, Matteo; Minei, Silvia; Garrone, Ornella; Bossi, Paolo (20 April 2023). "Why Oncologists Should Feel Directly Involved in Persuading Patients with Head and Neck Cancer to Quit Smoking" (in en). Oncology 101 (4): 252–256. doi:10.1159/000528345. ISSN 0030-2414. PMID 36538910. https://karger.com/OCL/article/doi/10.1159/000528345.

- ↑ von Kroge, Patricia R.; Bokemeyer, Frederike; Ghandili, Susanne; Bokemeyer, Carsten; Seidel, Christoph (18 September 2020). "The Impact of Smoking Cessation and Continuation on Recurrence and Survival in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer: A Systematic Review of the Literature" (in en). Oncology Research and Treatment 43 (10): 549–558. doi:10.1159/000509427. ISSN 2296-5270. PMID 32950990. https://karger.com/ORT/article/doi/10.1159/000509427.

- ↑ Descamps, Géraldine; Karaca, Yasemin; Lechien, Jérôme R; Kindt, Nadège; Decaestecker, Christine; Remmelink, Myriam; Larsimont, Denis; Andry, Guy et al. (2016-07-01). "Classical risk factors, but not HPV status, predict survival after chemoradiotherapy in advanced head and neck cancer patients" (in en). Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology 142 (10): 2185–2196. doi:10.1007/s00432-016-2203-7. ISSN 0171-5216. PMID 27370781.

- ↑ Desrichard, Alexis; Kuo, Fengshen; Chowell, Diego; Lee, Ken-Wing; Riaz, Nadeem; Wong, Richard J; Chan, Timothy A; Morris, Luc G T (2018-12-01). "Tobacco Smoking-Associated Alterations in the Immune Microenvironment of Squamous Cell Carcinomas" (in en). JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 110 (12): 1386–1392. doi:10.1093/jnci/djy060. ISSN 0027-8874. PMID 29659925. PMC 6292793. https://academic.oup.com/jnci/article/110/12/1386/4968036.

- ↑ Ang, K. Kian; Harris, Jonathan; Wheeler, Richard; Weber, Randal; Rosenthal, David I.; Nguyen-Tân, Phuc Felix; Westra, William H.; Chung, Christine H. et al. (2010-06-07). "Human Papillomavirus and Survival of Patients with Oropharyngeal Cancer" (in en). New England Journal of Medicine 363 (1): 24–35. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 20530316.

- ↑ "A novel application of the Margin of Exposure approach: segregation of tobacco smoke toxicants". Food and Chemical Toxicology 49 (11): 2921–2933. November 2011. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2011.07.019. PMID 21802474.

- ↑ "Acrylonitrile-induced oxidative stress and oxidative DNA damage in male Sprague-Dawley rats". Toxicological Sciences 111 (1): 64–71. September 2009. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfp133. PMID 19546159.

- ↑ "Genetic effects of oxidative DNA damages: comparative mutagenesis of the imidazole ring-opened formamidopyrimidines (Fapy lesions) and 8-oxo-purines in simian kidney cells". Nucleic Acids Research 34 (8): 2305–2315. 2006. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl099. PMID 16679449.

- ↑ "Is FapyG mutagenic?: Evidence from the DFT study". ChemPhysChem 14 (14): 3263–3270. October 2013. doi:10.1002/cphc.201300535. PMID 23934915.

- ↑ "Effects of base excision repair proteins on mutagenesis by 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine (8-hydroxyguanine) paired with cytosine and adenine". DNA Repair 9 (5): 542–550. May 2010. doi:10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.02.004. PMID 20197241.

- ↑ "Variant base excision repair proteins: contributors to genomic instability". Seminars in Cancer Biology 20 (5): 320–328. October 2010. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2010.10.010. PMID 20955798.

- ↑ "Smokeless Tobacco Use and the Risk of Head and Neck Cancer: Pooled Analysis of US Studies in the INHANCE Consortium". American Journal of Epidemiology 184 (10): 703–716. November 2016. doi:10.1093/aje/kww075. PMID 27744388.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Hecht, Stephen S.; Hatsukami, Dorothy K. (3 January 2022). "Smokeless tobacco and cigarette smoking: chemical mechanisms and cancer prevention" (in en). Nature Reviews Cancer 22 (3): 143–155. doi:10.1038/s41568-021-00423-4. ISSN 1474-175X. PMID 34980891.

- ↑ Wyss, Annah; Hashibe, Mia; Chuang, Shu-Chun; Lee, Yuan-Chin Amy; Zhang, Zuo-Feng; Yu, Guo-Pei; Winn, Deborah M.; Wei, Qingyi et al. (2013-09-01). "Cigarette, Cigar, and Pipe Smoking and the Risk of Head and Neck Cancers: Pooled Analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium" (in en). American Journal of Epidemiology 178 (5): 679–690. doi:10.1093/aje/kwt029. ISSN 1476-6256. PMID 23817919.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 "Effects of Electronic Cigarettes on Oral Cavity: A Systematic Review". The Journal of Evidence-Based Dental Practice 19 (4). December 2019. doi:10.1016/j.jebdp.2019.04.002. PMID 31843181.

- ↑ Esteban-Lopez, Maria; Perry, Marissa D.; Garbinski, Luis D.; Manevski, Marko; Andre, Mickensone; Ceyhan, Yasemin; Caobi, Allen; Paul, Patience et al. (23 June 2022). "Health effects and known pathology associated with the use of E-cigarettes" (in en). Toxicology Reports 9: 1357–1368. doi:10.1016/j.toxrep.2022.06.006. PMID 36561957. Bibcode: 2022ToxR....9.1357E.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Gallagher, Tyler J.; Chung, Ryan S.; Lin, Matthew E.; Kim, Ian; Kokot, Niels C. (2024-08-08). "Cannabis Use and Head and Neck Cancer". JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 150 (12): 1068–1075. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2024.2419. ISSN 2168-6181. PMID 39115834.

- ↑ Ghasemiesfe, Mehrnaz; Barrow, Brooke; Leonard, Samuel; Keyhani, Salomeh; Korenstein, Deborah (2019-11-27). "Association Between Marijuana Use and Risk of Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis" (in en). JAMA Network Open 2 (11): e1916318. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.16318. ISSN 2574-3805. PMID 31774524.

- ↑ Rodríguez-Molinero, Jesús; Migueláñez-Medrán, Blanca del Carmen; Puente-Gutiérrez, Cristina; Delgado-Somolinos, Esther; Martín Carreras-Presas, Carmen; Fernández-Farhall, Javier; López-Sánchez, Antonio Francisco (2021-04-15). "Association between Oral Cancer and Diet: An Update" (in en). Nutrients 13 (4): 1299. doi:10.3390/nu13041299. ISSN 2072-6643. PMID 33920788.

- ↑ Morze, Jakub; Danielewicz, Anna; Przybyłowicz, Katarzyna; Zeng, Hongmei; Hoffmann, Georg; Schwingshackl, Lukas (April 2021). "An updated systematic review and meta-analysis on adherence to mediterranean diet and risk of cancer" (in en). European Journal of Nutrition 60 (3): 1561–1586. doi:10.1007/s00394-020-02346-6. ISSN 1436-6207. PMID 32770356.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3 56.4 56.5 56.6 Barsouk, Adam; Aluru, John Sukumar; Rawla, Prashanth; Saginala, Kalyan; Barsouk, Alexander (2023-06-13). "Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Prevention of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma" (in en). Medical Sciences 11 (2): 42. doi:10.3390/medsci11020042. ISSN 2076-3271. PMID 37367741.

- ↑ Lian, Mei (30 January 2022). "Salted fish and processed foods intake and nasopharyngeal carcinoma risk: a dose–response meta-analysis of observational studies" (in en). European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology 279 (5): 2501–2509. doi:10.1007/s00405-021-07210-9. ISSN 0937-4477. PMID 35094122. https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00405-021-07210-9.

- ↑ Harvie, Michelle (2014-05-30). "Nutritional Supplements and Cancer: Potential Benefits and Proven Harms" (in en). American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book (34): e478–e486. doi:10.14694/EdBook_AM.2014.34.e478. ISSN 1548-8748. PMID 24857143. https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.14694/EdBook_AM.2014.34.e478.

- ↑ "Role of areca nut in betel quid-associated chemical carcinogenesis: current awareness and future perspectives". Oral Oncology 37 (6): 477–492. September 2001. doi:10.1016/S1368-8375(01)00003-3. PMID 11435174.

- ↑ Lesseur, Corina; Diergaarde, Brenda; Olshan, Andrew F; Wünsch-Filho, Victor; Ness, Andrew R; Liu, Geoffrey; Lacko, Martin; Eluf-Neto, José et al. (17 October 2016). "Genome-wide association analyses identify new susceptibility loci for oral cavity and pharyngeal cancer" (in en). Nature Genetics 48 (12): 1544–1550. doi:10.1038/ng.3685. ISSN 1061-4036. PMID 27749845.

- ↑ Shete, Sanjay; Liu, Hongliang; Wang, Jian; Yu, Robert; Sturgis, Erich M.; Li, Guojun; Dahlstrom, Kristina R.; Liu, Zhensheng et al. (2020-06-15). "A Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Two Novel Susceptible Regions for Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck" (in en). Cancer Research 80 (12): 2451–2460. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-2360. ISSN 0008-5472. PMID 32276964.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 El Hussein, Mohamed Toufic; Dhaliwal, Simreen (October 2023). "HPV vaccination for prevention of head and neck cancer among men" (in en). The Nurse Practitioner 48 (10): 25–32. doi:10.1097/01.NPR.0000000000000099. ISSN 0361-1817. PMID 37751612. https://journals.lww.com/10.1097/01.NPR.0000000000000099.

- ↑ Merriel, Samuel WD; Nadarzynski, Tom; Kesten, Joanna M; Flannagan, Carrie; Prue, Gillian (2018-08-30). "'Jabs for the boys': time to deliver on HPV vaccination recommendations" (in en). British Journal of General Practice 68 (674): 406–407. doi:10.3399/bjgp18X698429. ISSN 0960-1643. PMID 30166370.

- ↑ "HPV vaccine" (in en). NHS. 2024-03-06. https://www.nhs.uk/vaccinations/hpv-vaccine/.

- ↑ "Human papillomavirus types in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas worldwide: a systematic review". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 14 (2): 467–475. February 2005. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0551. PMID 15734974.

- ↑ "Epidemiology of human papillomavirus-related head and neck cancer". Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America 45 (4): 739–764. August 2012. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2012.04.003. PMID 22793850.

- ↑ "Molecular biology of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck". Journal of Clinical Pathology 59 (5): 445–453. May 2006. doi:10.1136/jcp.2003.007641. PMID 16644882.

- ↑ "Human papillomavirus (HPV) in head and neck cancer. An association of HPV 16 with squamous cell carcinoma of Waldeyer's tonsillar ring". Cancer 79 (3): 595–604. February 1997. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19970201)79:3<595::AID-CNCR24>3.0.CO;2-Y. PMID 9028373.

- ↑ "Human papillomavirus and head and neck cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Clinical Otolaryngology 31 (4): 259–266. August 2006. doi:10.1111/j.1749-4486.2006.01246.x. PMID 16911640. http://www.drchrishobbs.com/uploads/8/2/1/2/8212308/hpv__hnscc.pdf.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Sabatini, Maria Elisa; Chiocca, Susanna (2020-02-04). "Human papillomavirus as a driver of head and neck cancers" (in en). British Journal of Cancer 122 (3): 306–314. doi:10.1038/s41416-019-0602-7. ISSN 0007-0920. PMID 31708575.

- ↑ "Loss of gene function as a consequence of human papillomavirus DNA integration". International Journal of Cancer 131 (5): E593–E602. September 2012. doi:10.1002/ijc.27433. PMID 22262398.

- ↑ Stransky, Nicolas; Egloff, Ann Marie; Tward, Aaron D.; Kostic, Aleksandar D.; Cibulskis, Kristian; Sivachenko, Andrey; Kryukov, Gregory V.; Lawrence, Michael S. et al. (2011-08-26). "The Mutational Landscape of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma" (in en). Science 333 (6046): 1157–1160. doi:10.1126/science.1208130. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 21798893. Bibcode: 2011Sci...333.1157S.

- ↑ van Kempen, Pauline MW; Noorlag, Rob; Braunius, Weibel W; Stegeman, Inge; Willems, Stefan M; Grolman, Wilko (29 Oct 2013). "Differences in methylation profiles between HPV-positive and HPV-negative oropharynx squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic review" (in en). Epigenetics 9 (2): 194–203. doi:10.4161/epi.26881. ISSN 1559-2294. PMID 24169583.

- ↑ Nakagawa, Takuya; Kurokawa, Tomoya; Mima, Masato; Imamoto, Sakiko; Mizokami, Harue; Kondo, Satoru; Okamoto, Yoshitaka; Misawa, Kiyoshi et al. (2021-04-10). "DNA Methylation and HPV-Associated Head and Neck Cancer" (in en). Microorganisms 9 (4): 801. doi:10.3390/microorganisms9040801. ISSN 2076-2607. PMID 33920277.

- ↑ Hickman, E (2002-02-01). "The role of p53 and pRB in apoptosis and cancer". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 12 (1): 60–66. doi:10.1016/S0959-437X(01)00265-9. PMID 11790556. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0959437X01002659.

- ↑ "Risks and causes | Nasopharyngeal cancer". Cancer Research UK. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/nasopharyngeal-cancer/risks-causes.

- ↑ Li, Wenting; Duan, Xiaobing; Chen, Xingxing; Zhan, Meixiao; Peng, Haichuan; Meng, Ya; Li, Xiaobin; Li, Xian-Yang et al. (2023-01-11). "Immunotherapeutic approaches in EBV-associated nasopharyngeal carcinoma". Frontiers in Immunology 13. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.1079515. ISSN 1664-3224. PMID 36713430.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 "Oral cancer in patients after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: long-term follow-up suggests an increased risk for recurrence". Transplantation 90 (11): 1243–1244. December 2010. doi:10.1097/TP.0b013e3181f9caaa. PMID 21119507.

- ↑ Khlifi, Rim; Hamza-Chaffai, Amel (2010-10-15). "Head and neck cancer due to heavy metal exposure via tobacco smoking and professional exposure: A review" (in en). Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 248 (2): 71–88. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2010.08.003. PMID 20708025. Bibcode: 2010ToxAP.248...71K. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0041008X10002760.

- ↑ Bosetti, Cristina; Carioli, Greta; Santucci, Claudia; Bertuccio, Paola; Gallus, Silvano; Garavello, Werner; Negri, Eva; La Vecchia, Carlo (2020-08-15). "Global trends in oral and pharyngeal cancer incidence and mortality" (in en). International Journal of Cancer 147 (4): 1040–1049. doi:10.1002/ijc.32871. ISSN 0020-7136. PMID 31953840. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ijc.32871.

- ↑ Miranda-Filho, Adalberto; Bray, Freddie (25 January 2020). "Global patterns and trends in cancers of the lip, tongue and mouth" (in en). Oral Oncology 102. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.104551. PMID 31986342. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1368837519304610.

- ↑ Karp, Emily E.; Yin, Linda X.; Moore, Eric J.; Elias, Anna J.; O'Byrne, Thomas J.; Glasgow, Amy E.; Habermann, Elizabeth B.; Price, Daniel L. et al. (26 January 2021). "Barriers to Obtaining a Timely Diagnosis in Human Papillomavirus–Associated Oropharynx Cancer" (in en). Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery 165 (2): 300–308. doi:10.1177/0194599820982662. ISSN 0194-5998. PMID 33494648. https://aao-hnsfjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/0194599820982662.

- ↑ Schache, Andrew; Kerawala, Cyrus; Ahmed, Omar; Brennan, Peter A.; Cook, Florence; Garrett, Matthew; Homer, Jarrod; Hughes, Ceri et al. (3 March 2021). "British Association of Head and Neck Oncologists (BAHNO) standards 2020" (in en). Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine 50 (3): 262–273. doi:10.1111/jop.13161. ISSN 0904-2512. PMID 33655561.

- ↑ Marcus, Sonya; Timen, Micah; Dion, Gregory R.; Fritz, Mark A.; Branski, Ryan C.; Amin, Milan R. (19 February 2018). "Cost Analysis of Channeled, Distal Chip Laryngoscope for In-office Laryngopharyngeal Biopsies" (in en). Journal of Voice 33 (4): 575–579. doi:10.1016/j.jvoice.2018.01.011. PMID 29472150. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0892199717305222.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 85.2 Homer, Jarrod J; Winter, Stuart C; Abbey, Elizabeth C; Aga, Hiba; Agrawal, Reshma; ap Dafydd, Derfel; Arunjit, Takhar; Axon, Patrick et al. (14 March 2024). "Head and Neck Cancer: United Kingdom National Multidisciplinary Guidelines, Sixth Edition" (in en). The Journal of Laryngology & Otology 138 (S1): S1–S224. doi:10.1017/S0022215123001615. ISSN 0022-2151. PMID 38482835.

- ↑ Ye, Wenda; Arnaud, Ethan H.; Langerman, Alexander; Mannion, Kyle; Topf, Michael C. (1 May 2021). "Diagnostic approaches to carcinoma of unknown primary of the head and neck" (in en). European Journal of Cancer Care 30 (6). doi:10.1111/ecc.13459. ISSN 0961-5423. PMID 33932056.

- ↑ "Routine HPV Testing in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. EBS 5-9". May 2013. https://www.cancercare.on.ca/common/pages/UserFile.aspx?fileId=279838.

- ↑ Salmanpour, Mohammad R.; Hajianfar, Ghasem; Hosseinzadeh, Mahdi; Rezaeijo, Seyed Masoud; Hosseini, Mohammad Mehdi; Kalatehjari, Ehsanhosein; Harimi, Ali; Rahmim, Arman (18 March 2023). "Deep Learning and Machine Learning Techniques for Automated PET/CT Segmentation and Survival Prediction in Head and Neck Cancer". Springer. pp. 230–239. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-27420-6_23. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-27420-6_23.

- ↑ "Cancer of the upper aerodigestive tract: assessment and management in people aged 16 and over - Recommendations". 2016-02-10. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG36/chapter/Recommendations.

- ↑ Helliwell, Tim; Woolgar, Julia (November 2013). "Standards and datasets for reporting cancers. Dataset for histopathology reporting of salivary gland neoplasms". Royal College of Pathologists. https://www.rcpath.org/static/3d46a973-a5fd-49f5-87dc074b90a69b72/Dataset-for-histopathology-reporting-of-salivary-gland-neoplasms.pdf.

- ↑ "Diagnostic accuracy of Cyfra 21-1 for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis". European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 17 (17): 2383–2389. September 2013. PMID 24065233.

- ↑ "Pathology of Head and Neck Cancers I: Epithelial and Related Tumors". Head & Neck Cancer: Current Perspectives, Advances, and Challenges. Springer Science & Business Media. 24 May 2013. pp. 257–87. ISBN 978-94-007-5827-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=iaFEAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA267.

- ↑ "Treatment of locally advanced head and neck cancer: historical and critical review". Cancer Control 9 (5): 387–399. 2002. doi:10.1177/107327480200900504. PMID 12410178.

- ↑ Eyassu, Eyovel; Young, Michael (2023), "Nuclear Medicine PET/CT Head and Neck Cancer Assessment, Protocols, and Interpretation", StatPearls (Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing), PMID 34424632, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK573059/, retrieved 2023-11-24

- ↑ Oliver, Jamie R.; Persky, Michael J.; Wang, Binhuan; Duvvuri, Umamaheswar; Gross, Neil D.; Vaezi, Alec E.; Morris, Luc G. T.; Givi, Babak (2022-02-15). "Transoral robotic surgery adoption and safety in treatment of oropharyngeal cancers" (in en). Cancer 128 (4): 685–696. doi:10.1002/cncr.33995. ISSN 0008-543X. PMID 34762303.

- ↑ Lechien, Jerome R.; Fakhry, Nicolas; Saussez, Sven; Chiesa-Estomba, Carlos-Miguel; Chekkoury-Idrissi, Younes; Cammaroto, Giovanni; Melkane, Antoine E.; Barillari, Maria Rosaria et al. (10 June 2020). "Surgical, clinical and functional outcomes of transoral robotic surgery for supraglottic laryngeal cancers: A systematic review" (in en). Oral Oncology 109. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.104848. PMID 32534362.

- ↑ Lai, Katherine W. K.; Lai, Ronald; Lorincz, Balazs B.; Wang, Chen-Chi; Chan, Jason Y. K.; Yeung, David C. M. (2022-04-07). "Oncological and Functional Outcomes of Transoral Robotic Surgery and Endoscopic Laryngopharyngeal Surgery for Hypopharyngeal Cancer: A Systematic Review". Frontiers in Surgery 8. doi:10.3389/fsurg.2021.810581. ISSN 2296-875X. PMID 35464886.

- ↑ "Early Oral Tongue Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Sampling of Margins From Tumor Bed and Worse Local Control". JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 141 (12): 1104–1110. December 2015. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2015.1351. PMID 26225798.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ "Cardiovascular Complications of Cranial and Neck Radiation". Current Treatment Options in Cardiovascular Medicine 18 (7). July 2016. doi:10.1007/s11936-016-0468-4. PMID 27181400.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 Burke, G.; Faithfull, S.; Probst, H. (7 January 2022). "Radiation induced skin reactions during and following radiotherapy: A systematic review of interventions" (in en). Radiography 28 (1): 232–239. doi:10.1016/j.radi.2021.09.006. PMID 34649789.

- ↑ "FDA Approval for Docetaxel - National Cancer Institute". Cancer.gov. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/druginfo/fda-docetaxel.

- ↑ "Erythropoietin as an adjuvant treatment with (chemo) radiation therapy for head and neck cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3). July 2009. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006158.pub2. PMID 19588382.

- ↑ "Inoperable cancers killed by new laser surgery" The Times. UK. 3-April-2010 p15

- ↑ Blick, Stephanie K A; Scott, Lesley J (2007). "Cetuximab: A Review of its Use in Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck and Metastatic Colorectal Cancer" (in en). Drugs 67 (17): 2585–2607. doi:10.2165/00003495-200767170-00008. ISSN 0012-6667. PMID 18034592. http://link.springer.com/10.2165/00003495-200767170-00008.

- ↑ Cantwell, Linda A.; Fahy, Emer; Walters, Emily R.; Patterson, Joanne M. (26 November 2020). "Nutritional prehabilitation in head and neck cancer: a systematic review" (in en). Supportive Care in Cancer 30 (11): 8831–8843. doi:10.1007/s00520-022-07239-4. ISSN 0941-4355. PMID 35913625. https://livrepository.liverpool.ac.uk/3167149/1/Nutritional.prehab.pre-print.pdf.

- ↑ Muraro, Elena; Fanetti, Giuseppe; Lupato, Valentina; Giacomarra, Vittorio; Steffan, Agostino; Gobitti, Carlo; Vaccher, Emanuela; Franchin, Giovanni (10 July 2021). "Cetuximab in locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: Biological mechanisms involved in efficacy, toxicity and resistance" (in en). Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 164. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103424. PMID 34245856. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1040842821002122.

- ↑ "China approves first gene therapy". Nature Biotechnology 22 (1): 3–4. January 2004. doi:10.1038/nbt0104-3. PMID 14704685.

- ↑ "Targeted next-generation sequencing of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma identifies novel genetic alterations in HPV+ and HPV- tumors". Genome Medicine 5 (5). 2013. doi:10.1186/gm453. PMID 23718828.

- ↑ Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (2019-02-09). "pembrolizumab (KEYTRUDA)" (in en). FDA. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/pembrolizumab-keytruda.

- ↑ Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (2018-11-03). "Nivolumab for SCCHN" (in en). FDA. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/nivolumab-scchn.

- ↑ Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (2019-06-11). "FDA approves pembrolizumab for first-line treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma" (in en). FDA. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-pembrolizumab-first-line-treatment-head-and-neck-squamous-cell-carcinoma.

- ↑ "Late effects of head and neck cancer treatment" (in en). https://www.macmillan.org.uk/cancer-information-and-support/impacts-of-cancer/late-effects-of-head-and-neck-cancer-treatments.

- ↑ "Head and neck cancer symptoms" (in en). https://www.macmillan.org.uk/cancer-information-and-support/head-and-neck-cancer/signs-and-symptoms-of-head-and-neck-cancer.