Medical illustration

Topic: Medicine

From HandWiki - Reading time: 7 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 7 min

| Medical illustration | |

|---|---|

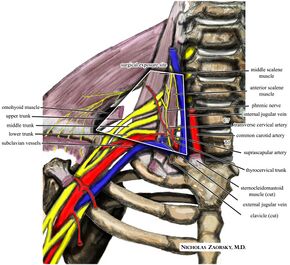

An illustration of the relevant neurovascular anatomy in anterior supraclavicular neurosurgical approach to the brachial plexus and subclavian vessels for thoracic outlet syndrome. | |

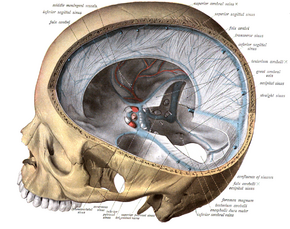

Anatomical illustration of a dissection of the skull showing meninges. A 1909 illustration from Sobotta's Atlas and Text-book of Human Anatomy. | |

| Anatomical terminology |

A medical illustration is a form of biological illustration that helps to record and disseminate medical, anatomical, and related knowledge.

History

Medical illustrations have been made possibly since the beginning of medicine[1] in any case for hundreds (or thousands) of years. Many illuminated manuscripts and Arabic scholarly treatises of the medieval period contained illustrations representing various anatomical systems (circulatory, nervous, urogenital), pathologies, or treatment methodologies. Many of these illustrations can look odd to modern eyes, since they reflect early reliance on classical scholarship (especially Galen) rather than direct observation, and the representation of internal structures can be fanciful. An early high-water mark was the 1543 CE publication of Andreas Vesalius's De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septum, which contained more than 600 exquisite woodcut illustrations based on careful observation of human dissection.

Since the time of the Leonardo da Vinci and his depictions of the human form, there have been great advancements in the art of representing the human body. The art has evolved over time from illustration to digital imaging using the technological advancements of the digital age. Berengario da Carpi was the first known anatomist to include medical illustration within his textbooks. Gray's Anatomy, originally published in 1858, is one well-known human anatomy textbook that showcases a variety of anatomy depiction techniques.[2]

In 1895, Konrad Roentgen, a German physicist discovered the X-Ray. Internal imaging became a reality after the invention of the X-Ray. Since then internal imaging has progressed to include ultrasonic, CT, and MRI imaging.[2]

As a profession, medical illustration has a more recent history. In the late 1890s, Max Brödel, a talented artist from Leipzig, was brought to The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore to illustrate for Harvey Cushing, William Halsted, Howard Kelly, and other notable clinicians. In addition to being an extraordinary artist, he created new techniques, such as carbon dust, that were especially suitable to his subject matter and then-current printing technologies. In 1911 he presided over the creation of the first academic department of medical illustration, which continues to this day. His graduates spread out across the world, and founded a number of the academic programs listed below under "Education".

Notable medical illustrators include Max Brödel and Dr. Frank H. Netter. For an online inventory of scientific illustrators including currently already more than 1000 medical illustrators active 1450-1950 and specializing in anatomy, dermatology and embryology, see the Stuttgart Database of Scientific Illustrators 1450–1950

Medical illustration is used in the history of medicine.[3]

Profession

Medical illustrators not only produce such material but can also function as consultants and administrators within the field of biocommunication. A certified medical illustrator continues to obtain extensive training in medicine, science, and art techniques throughout his or her career.

The Association of Medical Illustrators is an international organization founded in 1945, and incorporated in Illinois. Its members are primarily artists who create material designed to facilitate the recording and dissemination of medical and bioscientific knowledge through visual communication media. Members are involved not only in the creation of such material, but also serve in consultant, advisory, educational and administrative capacities in all aspects of bioscientific communications and related areas of visual education.

The professional objectives of the AMI are to promote the study and advancement of medical illustration and allied fields of visual communication, and to promote understanding and cooperation with the medical profession and related health science professions.

The AMI publishes an annual Medical Illustration Source Book which is distributed to creative and marketing professionals that regularly hire medical/scientific image makers for editorial, publishing, educational and advertising projects. There is a companion Source Book with searchable illustration, animation and multimedia portfolios from hundreds of artists in the field.

The obvious abilities necessary are to be able to visualize the subject-matter, some degree of originality in style of drawing and the refined skill of colour discrimination.[4]

Education

Most medical illustrators in the profession have a master's degree from an accredited graduate program in medical illustration or another advanced degree in either science or the arts. The Association of Medical Illustrators is a sponsor member of CAAHEP (Commission on Accreditation of Allied Health Education Programs), the organization that grants accreditation to the graduate programs in medical illustration upon recommendation of ARC-MI (Accreditation Review Committee for the Medical Illustrator) which is a standing committee of the AMI and a Committee on Accreditation of CAAHEP. Currently there are four accredited Programs in North America:

The Department of Art as Applied to Medicine on the East Baltimore Campus of the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions was the first program of its kind in the world. Endowed in 1911, the program has been in existence for over 90 years. In 1959, the Johns Hopkins University approved a two-year graduate program leading to the university-wide degree of Master of Arts in Medical and Biological Illustration. The academic calendar, faculty and student affairs are administered by The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. The program has been fully accredited since 1970, currently accredited by the Commission on Accreditation of Allied Health Education Programs (CAAHEP).

The Biomedical Visualization Program at the University of Illinois at Chicago's College of Applied Health Sciences is the second oldest school of medical illustration in the western hemisphere, founded in 1921 by Thomas Smith Jones (Jones also was co-founder of the Association of Medical Illustrators). The UIC program is located in the national healthcare and pharmaceutical hub of Chicago, and offers a market-based curriculum that includes the highest ends of technology (including the renowned Virtual Reality Medical Laboratory and a rigorous animation curriculum). Biomedical Visualization is located on the UIC Medical Center campus, home of the largest medical school in the United States. The UIC program blends the more traditional aspects of medical illustration and the emerging markets of digital, pharmaceutical, and "edutainment" industries. UIC previously offered an extensive study in the field of anaplastology (facial and somatic prosthetics) and medical sculpture, though it is no longer available in the current curriculum.[5] A two-year Master of Science (MS) in Biomedical Visualization degree is awarded, and the program is accredited by the Commission on Accreditation of Allied Health Education Programs (CAAHEP).

The Medical Illustration Graduate Program at Augusta University (formerly the Medical College of Georgia), in Augusta, Georgia is fully accredited by CAAHEP. Graduates receive a Master of Science in Medical Illustration. The first Master of Science degree in Medical Illustration at MCG was awarded in 1951. The program emphasizes anatomical and surgical illustration for print and electronic publication, as well as for projection and broadcast distribution. Because of the importance of good drawing skills, the students learn a variety of traditional illustration techniques during the first year. In addition, computer technologies and digital techniques, used to prepare both vector and raster images for print and motion media, are well and extensively integrated into the curriculum.

The Biomedical Communications Program at the University of Toronto. This program was begun in 1945 by Maria Wishart, a student of Max Brödel's. Faculty and graduates of the program contributed the drawings for Grant's Atlas of Anatomy, a renowned guide to dissection, structure, and function for medical students. The current two-year professional Master's program, offered through the Institute of Medical Science, emphasizes a research-based approach to the creation and evaluation of visual material for health promotion, medical education, and the process of scientific discovery.

The Biomedical Communication Graduate Program at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas. The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center was the first school in the world to offer a graduate degree in medical illustration in 1945. Lewis Boyd Waters, who studied under Max Brodel at Johns Hopkins in the 1920s, was a founding member of the medical school and was responsible for starting the master's program. Waters died in 1969 and was later succeeded by several of his students who continued and expanded the program. The program was designed to be an interdisciplinary program that provides opportunities for development of the skills and knowledge needed in the application of communications arts and technology to the health sciences. The program closed in 2012.

Technique

Medical illustrators create medical illustrations using traditional and digital techniques which can appear in medical textbooks, medical advertisements, professional journals, instructional videotapes and films, animations, web-based media, computer-assisted learning programs, exhibits, lecture presentations, general magazines and television. Although much medical illustration is designed for print or presentation media, medical illustrators also work in three dimensions, creating anatomical teaching models, patient simulators, games, and facial prosthetics.

The traditional tools of medical illustration are slowly being replaced and supplemented by a range of unique modern artistic practices. Three-dimensional renders and endoscopic cameras are replacing carbon dust and cadavers.

Additional images

-

Illustration from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of Anencephaly.

-

Illustration from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of a normal heart.

See also

- Max Brödel

- Illustration

- Biological illustration

- Medical photography

- Anatomical fugitive sheet

- Embryo drawing

- Frank H. Netter, prolific medical illustrator

- Garnet Jex, (1895–1979)

References

- Crosby, Ranice W. and John Cody. 1991. Max Brödel; The Man Who Put Art Into Medicine. New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Demarest, Robert J., editor. 1995. The History of The Association of Medical Illustrators, 1945-1995. Atlanta: The Association of Medical Illustrators.

- This article or a previous version of it contained material from http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/medart/; copied with permission.

Notes

- ↑ FM. Corl1, MR. Garland and EK. Fishman - Role of Computer Technology in Medical Illustration AJR December 2000 vol. 175 no. 6 1519-1524 Retrieved 2012-12-20

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Tsafrir, Jenni; Ohry, Avi (18 July 2008). "Medical illustration: from caves to cyberspace‡" (in en). Health Information & Libraries Journal 18 (2): 99–109. doi:10.1046/j.1471-1842.2001.d01-16.x. ISSN 1471-1834.

- ↑ Camillia Matuk (2006). "Seeing the Body: The Divergence of Ancient Chinese and Western Medical Illustration". Journal of Biocommunication 32 (1). http://www.sesp.northwestern.edu/docs/publications/6074956944509ac426aaa6.pdf.

- ↑ nih.gov Retrieved 2012-12-20

- ↑ "MS in Biomedical Visualization < University of Illinois at Chicago". https://catalog.uic.edu/gcat/colleges-schools/applied-health-sciences/bvis/ms/.

External links

- Association of Medical Illustrators

- Medical Illustration & Animation Source Book

- Article about Medical Illustrators on mshealthcenteers

- A list of medical images and illustrations

- Stuttgart Database of Scientific and Medical Illustrators 1450-1950 (DSI) (with more than 6200 entries and 20 search fields)

- Anatomical Charts and Essays at the University of Virginia

- Courtroom Medical Illustration

- Medical Illustrations digital collection from the University at Buffalo Libraries

KSF

KSF