Medical imaging in pregnancy

Topic: Medicine

From HandWiki - Reading time: 5 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 5 min

thumb|right|Obstetric ultrasonography showing a fetus at 14 weeks of gestational age, through the median plane.

Medical imaging in pregnancy may be indicated because of pregnancy complications, intercurrent diseases or routine prenatal care.

Options

Options for medical imaging in pregnancy include the following:

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without MRI contrast agents as well as obstetric ultrasonography are not associated with any risk for the mother or the fetus and are the imaging techniques of choice for pregnant women.[1]

- Projectional radiography, X-ray computed tomography and nuclear medicine result in some degree of ionizing radiation exposure but have with a few exceptions much lower radiation doses than what is associated with fetal harm.[1] They are indicated when ultrasonography or MRI is not readily available or not feasible for the diagnostic question at hand.[1]

- Radiocontrast agents, when orally administered, are harmless.[1] Intravenous administration of iodinated radiocontrast agents can cross the placenta and enter the fetal circulation, but animal studies have reported no teratogenic or mutagenic effects from its use. There have been theoretical concerns about the potential harm of free iodide on the fetal thyroid gland,[1] but multiple studies have shown that a single dose of intravenously administered iodinated contrast medium to a pregnant mother has no effect on neonatal thyroid function.[2] Nevertheless, it generally is recommended that radiocontrast only be used if required to obtain additional diagnostic information that will improve the care of the fetus or mother.[1]

Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), without MRI contrast agents, is not associated with any risk for the mother or the fetus, and together with medical ultrasonography, it is the technique of choice for medical imaging in pregnancy.[1]

Safety

For the first trimester, no known literature has documented specific adverse effects in human embryos or fetuses exposed to non-contrast MRI during the first trimester.[3] During the second and third trimesters, there is some evidence to support the absence of risk, including a retrospective study of 1737 prenatally exposed children, showing no significant difference in hearing, motor skills, or functional measures after a mean follow-up time of 2 years.[3]

Gadolinium contrast agents in the first trimester are associated with a slightly increased risk of a childhood diagnosis of several forms of rheumatism, inflammatory disorders, or infiltrative skin conditions, according to a retrospective study including 397 infants prenatally exposed to gadolinium contrast.[3] In the second and third trimesters, gadolinium contrast is associated with a slightly increased risk of stillbirth or neonatal death, by the same study.[3] Hence, is recommended that gadolinium contrast in MRI should be limited, and should only be used when it significantly improves diagnostic performance and is expected to improve fetal or maternal outcomes.[1]

Women have a legal right to not be forced to undergo medical imaging without first providing informed consent; a radiologist is usually the healthcare provider trained to enable informed consent.[4]

Common uses

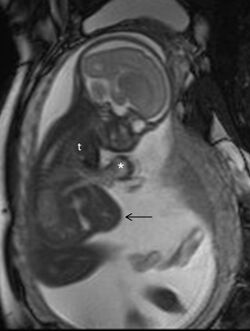

MRI is commonly used in pregnant women with acute abdominal pain and/or pelvic pain, or in suspected neurological disorders, placental diseases, tumors, infections, and/or cardiovascular diseases.[3] Appropriate use criteria by the American College of Radiology give a rating of ≥7 (usually appropriate) for non-contrast MRI for the following conditions:

- Acute non-localized pain in the right upper quadrant or right lower quadrant (in concurrent fever and leukocytosis)[3]

- Acute pelvic pain when a non-gynecological cause is suspected[3]

- Suspected biliary disease such as jaundice[3]

- Suspected pancreatic disease[3]

- New‐onset severe headache[3]

- Newly diagnosed cancer[3]

Radiography and nuclear medicine

Fetal effects by radiation dosage

Health effects of radiation may be grouped in two general categories:

- stochastic effects, i.e., radiation-induced cancer and heritable effects involving either cancer development in exposed individuals owing to mutation of somatic cells or heritable disease in their offspring owing to mutation of reproductive (germ) cells.[5] The risk for developing radiation-induced cancer at some point in life is greater when exposing a fetus than an adult, both because the cells are more vulnerable when they are growing, and because there is much longer lifespan after the dose to develop cancer.

- deterministic effects (harmful tissue reactions) due in large part to the killing/ malfunction of cells following high doses.

The determinstistic effects have been studied at for example survivors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and cases of where radiation therapy has been necessary during pregnancy:

| Gestational age | Embryonic age | Effects | Estimated threshold dose (mGy) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 to 4 weeks | 0 to 2 weeks | Miscarriage or none (all or nothing) | 50 - 100[1] |

| 4 to 10 weeks | 2 to 8 weeks | Structural birth defects | 200[1] |

| Growth restriction | 200 - 250[1] | ||

| 10 to 17 weeks | 8 to 15 weeks | Severe intellectual disability | 60 - 310[1] |

| 18 to 27 weeks | 16 to 25 weeks | Severe intellectual disability (lower risk) | 250 - 280[1] |

The intellectual deficit has been estimated to be about 25 IQ-points per 1,000 mGy at 10 to 17 weeks of gestational age.[1]

Fetal radiation dosages by imaging method

| Imaging method | Fetal absorbed dose of ionizing radiation (mGy) |

|---|---|

| Projectional radiography | |

| Cervical spine by 2 views (anteroposterior and lateral) | < 0.001[1] |

| Extremities | < 0.001[1] |

| Mammography by 2 views | 0.001 - 0.01[1] |

| Chest | 0.0005 - 0.01[1] |

| Abdominal | 0.1 - 3.0[1] |

| Lumbar spine | 1.0 - 10[1] |

| Intravenous pyelogram | 5 - 10[1] |

| Double contrast barium enema | 1.0 - 20[1] |

| CT scan | |

| Head or neck | 1.0 - 10[1] |

| Chest, including CT pulmonary angiogram | 0.01 - 0.66[1] |

| Limited CT pelvimetry by single axial slice through femoral heads | < 1[1] |

| Abdominal | 1.3 - 35[1] |

| Pelvic | 10 - 50[1] |

| Nuclear medicine | |

| Low-dose perfusion scintigraphy | 0.1 - 0.5[1] |

| Bone scintigraphy with 99mTc | 4 - 5[1] |

| Pulmonary digital subtraction angiography | 0.5[1] |

| Whole-body PET/CT with 18F' | 10 - 15[1] |

Radiation-induced breast cancer

The risk for the mother of later acquiring radiation-induced breast cancer seems to be particularly high for radiation doses during pregnancy.[6]

This is an important factor when for example determining whether a ventilation/perfusion scan (V/Q scan) or a CT pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) is the optimal investigation in pregnant women with suspected pulmonary embolism. A V/Q scan confers a higher radiation dose to the fetus, while a CTPA confers a much higher radiation dose to the mother's breasts. A review from the United Kingdom in 2005 considered CTPA to be generally preferable in suspected pulmonary embolism in pregnancy because of higher sensitivity and specificity as well as a relatively modest cost.[7]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 1.29 1.30 "Guidelines for Diagnostic Imaging During Pregnancy and Lactation". https://www.acog.org/en/Clinical/Clinical%20Guidance/Committee%20Opinion/Articles/2017/10/Guidelines%20for%20Diagnostic%20Imaging%20During%20Pregnancy%20and%20Lactation. February 2016

- ↑ "ACR Manual on Contrast Media. Version 10.3". American College of Radiology Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media. 2017. https://www.acr.org/~/media/37D84428BF1D4E1B9A3A2918DA9E27A3.pdf.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 Mervak, Benjamin M.; Altun, Ersan; McGinty, Katrina A.; Hyslop, W. Brian; Semelka, Richard C.; Burke, Lauren M. (2019). "MRI in pregnancy: Indications and practical considerations". Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 49 (3): 621–631. doi:10.1002/jmri.26317. ISSN 1053-1807. PMID 30701610.

- ↑ Emmerson, Benjamin; Young, Michael (2023), "Radiology Patient Safety and Communication", StatPearls (Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing), PMID 33620790, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567713, retrieved 2023-11-24

- ↑ Paragraph 55 of "The 2007 Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection". 2007. http://www.icrp.org/publication.asp?id=ICRP%20Publication%20103. Ann. ICRP 37 (2-4)

- ↑ Ronckers, Cécile M; Erdmann, Christine A; Land, Charles E (2004). "Radiation and breast cancer: a review of current evidence". Breast Cancer Research 7 (1): 21–32. doi:10.1186/bcr970. ISSN 1465-542X. PMID 15642178.

- ↑ Mallick, Srikumar; Petkova, Dimitrina (2006). "Investigating suspected pulmonary embolism during pregnancy". Respiratory Medicine 100 (10): 1682–1687. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2006.02.005. ISSN 0954-6111. PMID 16549345.

|

KSF

KSF