Neurodevelopmental disorder

Topic: Medicine

From HandWiki - Reading time: 17 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 17 min

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

(Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

| Neurodevelopmental disorder | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Psychiatry, neurology |

Neurodevelopmental disorders are a group of mental conditions negatively affecting the development of the nervous system, which includes the brain and spinal cord. According to the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) published in 2013, these conditions generally appear in early childhood, usually before children start school, and can persist into adulthood.[1] The key characteristic of all these disorders is that they negatively impact a person's functioning in one or more domains of life (personal, social, academic, occupational) depending on the disorder and deficits it has caused. All of these disorders and their levels of impairment exist on a spectrum, and affected individuals can experience varying degrees of symptoms and deficits, despite having the same diagnosis.[1][2]

The DSM-5 classifies neurodevelopmental disorders into six overarching groups: intellectual, communication, autism, attention deficit hyperactivity, motor, and specific learning disorders.[1] Often one disorder is accompanied by another.[2]

Classification

Intellectual disability

Intellectual disability, also known as general learning disability is a disorder that affects the ability to learn, retain, or process information; to think critically or abstractly, and to solve problems. Adaptive behaviour is limited, affecting daily living activities. Global developmental delay is categorized under intellectual disability and is diagnosed when several areas of intellectual functioning are affected.[3]

Communication disorders

A communication disorder is any disorder that affects an individual's ability to comprehend, detect, or apply language and speech to engage in dialogue effectively with others.[4] This also encompasses deficiencies in verbal and nonverbal communication styles.[5] Examples include stuttering, sound substitution, inability to understand or use one's native language.[6]

Autism spectrum disorder

Autism, also called autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or autism spectrum condition (ASC), is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by symptoms of deficient reciprocal social communication and the presence of restricted, repetitive, and inflexible patterns of behavior. While its severity and specific manifestations vary widely across the spectrum, autism generally affects a person's ability to understand and connect with others and adapt to everyday situations. Like most developmental disorders, autism exists along a continuum of symptom severity, subjective distress, and functional impairment. A consequence of this dimensionality is substantial variability across autistic persons with respect to both the nature and the extent of required supports.

A formal diagnosis of ASD requires not merely the presence of ASD symptoms, but symptoms that cause significant impairment in multiple domains of functioning, in addition to being excessive or atypical enough to be developmentally and socioculturally inappropriate.[7][8]

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by executive dysfunction occasioning symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, impulsivity and emotional dysregulation that are excessive and pervasive, impairing in multiple contexts, and developmentally-inappropriate.[3][9][10][11]

ADHD symptoms arise from executive dysfunction,[20] and emotional dysregulation is often considered a core symptom.[24] Difficulties in self-regulation such as time management, inhibition and sustained attention may cause poor professional performance, relationship difficulties and numerous health risks,[25][26] collectively predisposing to a diminished quality of life[27] and a direct average reduction in life expectancy of 13 years.[28][29] ADHD is associated with other neurodevelopmental and mental disorders as well as non-psychiatric disorders, which can cause additional impairment.[11]

Motor disorders

Motor disorders including developmental coordination disorder, stereotypic movement disorder, and tic disorders (such as Tourette's syndrome), and apraxia of speech.

Specific learning disorders

Deficits in any area of information processing can manifest in a variety of specific learning disabilities (SLD). It is possible for an individual to have more than one of these difficulties. This is referred to as comorbidity or co-occurrence of learning disabilities.[30]

Currently being researched

There are neurodevelopmental research projects examining potential new classifications of disorders including:

- Nonverbal learning disorder (NLD or NVLD), a neurodevelopmental disorder thought to be linked to white matter in the right hemisphere of the brain and generally considered to include (a) low visuospatial intelligence; (b) discrepancy between verbal and visuospatial intelligence; (c) visuoconstructive and fine-motor coordination skills; (d) visuospatial memory tasks; (e) reading better than mathematical achievement; and (f) socioemotional skills.[31][32][33] While Nonverbal learning disorder is not categorized in the ICD or DSM as a discrete classification, "the majority of researchers and clinicians agree that the profile of NLD clearly exists (but see Spreen, 2011, for an exception[34]), but they disagree on the need for a specific clinical category and on the criteria for its identification."[35]

Presentation

Consequences

The multitude of neurodevelopmental disorders spans a wide range of associated symptoms and severity, resulting in different degrees of mental, emotional, physical, and economic consequences for individuals, and in turn families, social groups, and society.[2]

Causes

The development of the nervous system is tightly regulated and timed; it is influenced by both genetic programs and the prenatal environment. Any significant deviation from the normal developmental trajectory early in life can result in missing or abnormal neuronal architecture or connectivity.[36] Because of the temporal and spatial complexity of the developmental trajectory, there are many potential causes of neurodevelopmental disorders that may affect different areas of the nervous system at different times and ages. These range from social deprivation, genetic and metabolic diseases, immune disorders, infectious diseases, nutritional factors, physical trauma, and toxic and prenatal environmental factors. Some neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism and other pervasive developmental disorders, are considered multifactorial syndromes which have many causes that converge to a more specific neurodevelopmental manifestation.[37] Some deficits may be predicted from observed deviations in the maturation patterns of the infant gut microbiome.[38]

Social deprivation

Deprivation from social and emotional care causes severe delays in brain and cognitive development.[39] Studies with children growing up in Romanian orphanages during Nicolae Ceauşescu's regime reveal profound effects of social deprivation and language deprivation on the developing brain. These effects are time-dependent. The longer children stayed in negligent institutional care, the greater the consequences. By contrast, adoption at an early age mitigated some of the effects of earlier institutionalization.[40]

Genetic disorders

A prominent example of a genetically determined neurodevelopmental disorder is trisomy 21, also known as Down syndrome. This disorder usually results from an extra chromosome 21,[41] although in uncommon instances it is related to other chromosomal abnormalities such as translocation of the genetic material. It is characterized by short stature, epicanthal (eyelid) folds, abnormal fingerprints, and palm prints, heart defects, poor muscle tone (delay of neurological development), and intellectual disabilities (delay of intellectual development).[42]

Less commonly known genetically determined neurodevelopmental disorders include Fragile X syndrome. Fragile X syndrome was first described in 1943 by Martin and Bell, studying persons with family history of sex-linked "mental defects".[43] Rett syndrome, another X-linked disorder, produces severe functional limitations.[44] Williams syndrome is caused by small deletions of genetic material from chromosome 7.[45] The most common recurrent copy number variation disorder is DiGeorge syndrome (22q11.2 deletion syndrome), followed by Prader-Willi syndrome and Angelman syndrome.[46]

Immune dysfunction

Immune reactions during pregnancy, both maternal and of the developing child, may produce neurodevelopmental disorders. One typical immune reaction in infants and children is PANDAS,[47] or Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal infection.[48] Another disorder is Sydenham's chorea, which results in more abnormal movements of the body and fewer psychological sequellae. Both are immune reactions against brain tissue that follow infection by Streptococcus bacteria. Susceptibility to these immune diseases may be genetically determined,[49] so sometimes several family members may have one or both of them following an epidemic of Strep infection.

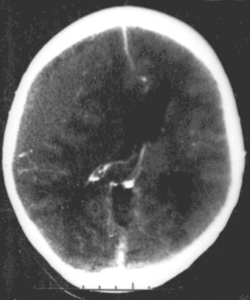

Infectious diseases

Systemic infections can result in neurodevelopmental consequences, when they occur in infancy and childhood of humans, but would not be called a primary neurodevelopmental disorder. For example HIV[50] Infections of the head and brain, like brain abscesses, meningitis or encephalitis have a high risk of causing neurodevelopmental problems and eventually a disorder. For example, measles can progress to subacute sclerosing panencephalitis.

A number of infectious diseases can be transmitted congenitally (either before or at birth), and can cause serious neurodevelopmental problems, as for example the viruses HSV, CMV, rubella (congenital rubella syndrome), Zika virus, or bacteria like Treponema pallidum in congenital syphilis, which may progress to neurosyphilis if it remains untreated. Protozoa like Plasmodium[50] or Toxoplasma which can cause congenital toxoplasmosis with multiple cysts in the brain and other organs, leading to a variety of neurological deficits.

Some cases of schizophrenia may be related to congenital infections, though the majority are of unknown causes.[51]

Metabolic disorders

Metabolic disorders in either the mother or the child can cause neurodevelopmental disorders. Two examples are diabetes mellitus (a multifactorial disorder) and phenylketonuria (an inborn error of metabolism). Many such inherited diseases may directly affect the child's metabolism and neural development[52] but less commonly they can indirectly affect the child during gestation. (See also teratology).

In a child, type 1 diabetes can produce neurodevelopmental damage by the effects of excess or insufficient glucose. The problems continue and may worsen throughout childhood if the diabetes is not well controlled.[53] Type 2 diabetes may be preceded in its onset by impaired cognitive functioning.[54]

A non-diabetic fetus can also be subjected to glucose effects if its mother has undetected gestational diabetes. Maternal diabetes causes excessive birth size, making it harder for the infant to pass through the birth canal without injury or it can directly produce early neurodevelopmental deficits. Usually the neurodevelopmental symptoms will decrease in later childhood.[55]

Phenylketonuria, also known as PKU, can induce neurodevelopmental problems and children with PKU require a strict diet to prevent intellectual disability and other disorders. In the maternal form of PKU, excessive maternal phenylalanine can be absorbed by the fetus even if the fetus has not inherited the disease. This can produce intellectual disability and other disorders.[56][57]

Nutrition

Nutrition disorders and nutritional deficits may cause neurodevelopmental disorders, such as spina bifida, and the rarely occurring anencephaly, both of which are neural tube defects with malformation and dysfunction of the nervous system and its supporting structures, leading to serious physical disability and emotional sequelae. The most common nutritional cause of neural tube defects is folic acid deficiency in the mother, a B vitamin usually found in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and milk products.[58][59] (Neural tube defects are also caused by medications and other environmental causes, many of which interfere with folate metabolism, thus they are considered to have multifactorial causes.)[60] Another deficiency, iodine deficiency, produces a spectrum of neurodevelopmental disorders ranging from mild emotional disturbance to severe intellectual disability. (see also congenital iodine deficiency syndrome).[61]

Excesses in both maternal and infant diets may cause disorders as well, with foods or food supplements proving toxic in large amounts. For instance in 1973 K.L. Jones and D.W. Smith of the University of Washington Medical School in Seattle found a pattern of "craniofacial, limb, and cardiovascular defects associated with prenatal onset growth deficiency and developmental delay" in children of alcoholic mothers, now called fetal alcohol syndrome, It has significant symptom overlap with several other entirely unrelated neurodevelopmental disorders.[62]

Physical trauma

Brain trauma in the developing human is a common cause (over 400,000 injuries per year in the US alone, without clear information as to how many produce developmental sequellae)[63] of neurodevelopmental syndromes. It may be subdivided into two major categories, congenital injury (including injury resulting from otherwise uncomplicated premature birth)[64] and injury occurring in infancy or childhood. Common causes of congenital injury are asphyxia (obstruction of the trachea), hypoxia (lack of oxygen to the brain), and the mechanical trauma of the birth process itself.[65]

Placenta

Although it not clear yet as strong is the correlation between placenta and brain, a growing number of studies are linking placenta to fetal brain development.[66]

Diagnosis

Neurodevelopmental disorders are diagnosed by evaluating the presence of characteristic symptoms or behaviors in a child, typically after a parent, guardian, teacher, or other responsible adult has raised concerns to a doctor.[67]

Neurodevelopmental disorders may also be confirmed by genetic testing. Traditionally, disease related genetic and genomic factors are detected by karyotype analysis, which detects clinically significant genetic abnormalities for 5% of children with a diagnosed disorder. As of 2017[update], chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) was proposed to replace karyotyping because of its ability to detect smaller chromosome abnormalities and copy-number variants, leading to greater diagnostic yield in about 20% of cases.[46] The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommend CMA as standard of care in the US.[46]

Management

Managing these disorders requires the involvement of professionals. After diagnosis, Parents or caregivers should engage the services of therapists depending on the challenges the individual is faced with, it is also important that they get help, as early intervention can help them overcome these challenges and generally improve their well-being.

See also

- Developmental disability

- Epigenetics

- Microcephaly

- Teratology

- TRPM3-related neurodevelopmental disorder

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed.). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association. 2013. pp. 31–33. ISBN 978-0-89042-554-1.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Neurodevelopmental disorders-the history and future of a diagnostic concept". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 22 (1): 65–72. March 2020. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2020.22.1/macrocq. PMID 32699506.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed.). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association. 2013. pp. 58–65. ISBN 978-0-89042-554-1.

- ↑ Collins, John William. "The greenwood dictionary of education". Greenwood, 2011. page 86. ISBN 978-0-313-37930-7

- ↑ "Definitions of Communication Disorders and Variations" (in en). 1993. https://www.asha.org/policy/rp1993-00208/.

- ↑ Gleason, Jean Berko (2001). The development of language. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 978-0-205-31636-6. OCLC 43694441. https://archive.org/details/developmentoflan00glea.

- ↑ "Autism spectrum disorder". https://icd.who.int/browse/2024-01/mms/en#437815624.

- ↑ "IACC Subcommittee Diagnostic Criteria - DSM-5 Planning Group". https://iacc.hhs.gov/about-iacc/subcommittees/resources/dsm5-diagnostic-criteria.shtml.

- ↑ Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR) ed.). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing. February 2022. ISBN 978-0-89042-575-6. OCLC 1288423302.

- ↑ "Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: legal and ethical aspects". Archives of Disease in Childhood 91 (2): 192–194. February 2006. doi:10.1136/adc.2004.064576. PMID 16428370.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "The World Federation of ADHD International Consensus Statement: 208 Evidence-based conclusions about the disorder". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews (Elsevier BV) 128: 789–818. September 2021. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.01.022. ISSN 0149-7634. PMID 33549739.

- ↑ "The Neurocognitive Profile of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Review of Meta-Analyses". Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology 33 (2): 143–157. March 2018. doi:10.1093/arclin/acx055. PMID 29106438.

- ↑ "Neuropsychological performance in adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis of empirical data". Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology 20 (6): 727–744. August 2005. doi:10.1016/j.acn.2005.04.005. PMID 15953706.

- ↑ "Meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of inhibition and attention in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: exploring task-specific, stimulant medication, and age effects". JAMA Psychiatry 70 (2): 185–198. February 2013. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.277. PMID 23247506.

- ↑ "Brain Imaging of the Cortex in ADHD: A Coordinated Analysis of Large-Scale Clinical and Population-Based Samples". The American Journal of Psychiatry 176 (7): 531–542. July 2019. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.18091033. PMID 31014101.

- ↑ "ADD/ADHD and Impaired Executive Function in Clinical Practice". Current Psychiatry Reports 10 (5): 407–411. October 2008. doi:10.1007/s11920-008-0065-7. PMID 18803914.

- ↑ "Chapters 10 and 13". Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2009. pp. 266, 315, 318–323. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4. "Early results with structural MRI show thinning of the cerebral cortex in ADHD subjects compared with age-matched controls in prefrontal cortex and posterior parietal cortex, areas involved in working memory and attention."

- ↑ "Executive functions". Annual Review of Psychology 64: 135–168. 2013. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750. PMID 23020641. "EFs and prefrontal cortex are the first to suffer, and suffer disproportionately, if something is not right in your life. They suffer first, and most, if you are stressed (Arnsten 1998, Liston et al. 2009, Oaten & Cheng 2005), sad (Hirt et al. 2008, von Hecker & Meiser 2005), lonely (Baumeister et al. 2002, Cacioppo & Patrick 2008, Campbell et al. 2006, Tun et al. 2012), sleep deprived (Barnes et al. 2012, Huang et al. 2007), or not physically fit (Best 2010, Chaddock et al. 2011, Hillman et al. 2008). Any of these can cause you to appear to have a disorder of EFs, such as ADHD, when you do not.".

- ↑ "Executive Functioning Theory and ADHD". Handbook of Executive Functioning. New York, NY: Springer. 2014. pp. 107–120. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-8106-5_7. ISBN 978-1-4614-8106-5.

- ↑ [12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19]

- ↑ "Emotional dysregulation in adult ADHD: What is the empirical evidence?". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics 12 (10): 1241–1251. October 2012. doi:10.1586/ern.12.109. PMID 23082740.

- ↑ "Practitioner Review: Emotional dysregulation in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder - implications for clinical recognition and intervention". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 60 (2): 133–150. February 2019. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12899. PMID 29624671.

- ↑ "Emotion dysregulation in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". The American Journal of Psychiatry 171 (3): 276–293. March 2014. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13070966. PMID 24480998.

- ↑ [21][22][23]

- ↑ "The Nature of Executive Function (EF) Deficits in Daily Life Activities in Adults with ADHD and Their Relationship to Performance on EF Tests" (in en). Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 33 (2): 137–158. 2011-06-01. doi:10.1007/s10862-011-9217-x. ISSN 1573-3505.

- ↑ "Educational and Health Outcomes of Children Treated for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder". JAMA Pediatrics 171 (7): e170691. July 2017. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0691. PMID 28459927.

- ↑ "Meta-analysis of quality of life in children and adolescents with ADHD: By both parent proxy-report and child self-report using PedsQL™". Research in Developmental Disabilities 51-52: 160–172. 2016-04-01. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2015.11.009. PMID 26829402.

- ↑ "Hyperactive Child Syndrome and Estimated Life Expectancy at Young Adult Follow-Up: The Role of ADHD Persistence and Other Potential Predictors". Journal of Attention Disorders 23 (9): 907–923. July 2019. doi:10.1177/1087054718816164. PMID 30526189.

- ↑ "The Adverse Health Outcomes, Economic Burden, and Public Health Implications of Unmanaged Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): A Call to Action Resulting from CHADD Summit, Washington, DC, October 17, 2019". Journal of Attention Disorders 26 (6): 807–808. April 2022. doi:10.1177/10870547211036754. PMID 34585995.

- ↑ Kirby A (2011-10-26). Dyslexia, Dyspraxia & Overlapping Learning Difficulties. Retrieved 2024-11-29 – via YouTube.

- ↑ "Nonverbal learning disability (developmental visuospatial disorder)". Neurocognitive Development: Disorders and Disabilities. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 174. 2020. pp. 83–91. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-64148-9.00007-7. ISBN 978-0-444-64148-9.

- ↑ "Nonverbal Learning Disabilities (Nld) – Clinical Description about Neurodevelopmental Disabilities". Archives in Neurology & Neuroscience 4 (1). 2019-06-18. doi:10.33552/ANN.2019.04.000579.

- ↑ "Nonverbal learning disability (developmental visuospatial disorder)" (in en). Neurocognitive Development: Disorders and Disabilities. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 174. Elsevier. 2020. pp. 83–91. doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-64148-9.00007-7. ISBN 978-0-444-64148-9.

- ↑ "Nonverbal learning disabilities: a critical review". Child Neuropsychology 17 (5): 418–443. September 2011. doi:10.1080/09297049.2010.546778. PMID 21462003. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09297049.2010.546778. Retrieved 2021-04-29.

- ↑ "An analysis of the criteria used to diagnose children with Nonverbal Learning Disability (NLD)". Child Neuropsychology 20 (3): 255–280. 2014-05-04. doi:10.1080/09297049.2013.796920. PMID 23705673.

- ↑ "Temporal specification and bilaterality of human neocortical topographic gene expression". Neuron 81 (2): 321–332. January 2014. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2013.11.018. PMID 24373884.

- ↑ "Epigenetic overlap in autism-spectrum neurodevelopmental disorders: MECP2 deficiency causes reduced expression of UBE3A and GABRB3". Human Molecular Genetics 14 (4): 483–492. February 2005. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddi045. PMID 15615769.

- ↑ Sizemore, Nicholas; Oliphant, Kaitlyn; Zheng, Ruolin; Martin, Camilia R.; Claud, Erika C.; Chattopadhyay, Ishanu (2024-04-12). "A digital twin of the infant microbiome to predict neurodevelopmental deficits" (in en). Science Advances 10 (15). doi:10.1126/sciadv.adj0400. ISSN 2375-2548. PMID 38598636. Bibcode: 2024SciA...10J.400S.

- ↑ "Children in Institutional Care: Delayed Development and Resilience". Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 76 (4): 8–30. December 2011. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5834.2011.00626.x. PMID 25125707.

- ↑ "Cognitive recovery in socially deprived young children: the Bucharest Early Intervention Project". Science 318 (5858): 1937–1940. December 2007. doi:10.1126/science.1143921. PMID 18096809. Bibcode: 2007Sci...318.1937N.

- ↑ "Down syndrome: An integrative review". Journal of Neonatal Nursing 24 (5): 235–241. October 2018. doi:10.1016/j.jnn.2018.01.001.

- ↑ "Facts about down syndrome". National Association of Down Syndrome. http://www.nads.org/pages_new/facts.html.

- ↑ "A Pedigree of Mental Defect Showing Sex-Linkage". Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry 6 (3–4): 154–157. July 1943. doi:10.1136/jnnp.6.3-4.154. PMID 21611430.

- ↑ "Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2". Nature Genetics 23 (2): 185–188. October 1999. doi:10.1038/13810. PMID 10508514.

- ↑ "Submicroscopic deletion in patients with Williams-Beuren syndrome influences expression levels of the nonhemizygous flanking genes". American Journal of Human Genetics 79 (2): 332–341. August 2006. doi:10.1086/506371. PMID 16826523.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 "Chromosomal Microarray Testing for Children With Unexplained Neurodevelopmental Disorders". JAMA 317 (24): 2545–2546. June 2017. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.7272. PMID 28654998.

- ↑ "Anti-brain antibodies in PANDAS versus uncomplicated streptococcal infection". Pediatric Neurology 30 (2): 107–110. February 2004. doi:10.1016/S0887-8994(03)00413-2. PMID 14984902.

- ↑ "Incidence of anti-brain antibodies in children with obsessive-compulsive disorder". The British Journal of Psychiatry 187 (4): 314–319. October 2005. doi:10.1192/bjp.187.4.314. PMID 16199788.

- ↑ "Genetics of childhood disorders: XXXIII. Autoimmunity, part 6: poststreptococcal autoimmunity". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 40 (12): 1479–1482. December 2001. doi:10.1097/00004583-200112000-00021. PMID 11765296. http://www.med.yale.edu/chldstdy/plomdevelop/genetics/01decgen.htm. Retrieved 2008-08-17.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 "Reducing neurodevelopmental disorders and disability through research and interventions". Nature 527 (7578): S155–S160. November 2015. doi:10.1038/nature16029. PMID 26580321. Bibcode: 2015Natur.527S.155B.

- ↑ "Prenatal infection as a risk factor for schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Bulletin 32 (2): 200–202. April 2006. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbj052. PMID 16469941.

- ↑ "Fatty acid metabolism in neurodevelopmental disorder: a new perspective on associations between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, dyslexia, dyspraxia and the autistic spectrum". Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes, and Essential Fatty Acids 63 (1–2): 1–9. July 2000. doi:10.1054/plef.2000.0184. PMID 10970706.

- ↑ "Neuropsychological profiles of children with type 1 diabetes 6 years after disease onset". Diabetes Care 24 (9): 1541–1546. September 2001. doi:10.2337/diacare.24.9.1541. PMID 11522696.

- ↑ "Cognitive function in children and subsequent type 2 diabetes". Diabetes Care 31 (3): 514–516. March 2008. doi:10.2337/dc07-1399. PMID 18083794.

- ↑ "Neurodevelopmental outcome at early school age of children born to mothers with gestational diabetes". Archives of Disease in Childhood. Fetal and Neonatal Edition 81 (1): F10–F14. July 1999. doi:10.1136/fn.81.1.F10. PMID 10375355.

- ↑ "Maternal phenylketonuria: report from the United Kingdom Registry 1978-97". Archives of Disease in Childhood 90 (2): 143–146. February 2005. doi:10.1136/adc.2003.037762. PMID 15665165.

- ↑ "Maternal Phenylketonuria Collaborative Study (MPKUCS) offspring: facial anomalies, malformations, and early neurological sequelae". American Journal of Medical Genetics 69 (1): 89–95. March 1997. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19970303)69:1<89::AID-AJMG17>3.0.CO;2-K. PMID 9066890.

- ↑ "Folic Acid". March of Dimes. http://www.marchofdimes.org/pregnancy/folic-acid.aspx.

- ↑ "Folate (Folacin, Folic Acid)". Ohio State University Extension. http://ohioline.osu.edu/hyg-fact/5000/5553.html.

- ↑ "Folic scid: topic home". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/folicacid/.

- ↑ "Iodine deficiency in pregnancy: the effect on neurodevelopment in the child". Nutrients 3 (2): 265–273. February 2011. doi:10.3390/nu3020265. PMID 22254096.

- ↑ Fetal alcohol syndrome: guidelines for referral and diagnosis (PDF). CDC (July 2004). Retrieved on 2007-04-11

- ↑ "Facts About TBI". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/tbi/FactSheets/Facts_About_TBI.pdf.

- ↑ "Is schizophrenia a neurodevelopmental disorder?". British Medical Journal 295 (6600): 681–682. September 1987. doi:10.1136/bmj.295.6600.681. PMID 3117295.

- ↑ "Birth Injury: Birth Asphyxia and Birth Trauma". Academic Forensic Pathology 8 (4): 788–864. December 2018. doi:10.1177/1925362118821468. PMID 31240076.

- ↑ "Placental programming of neuropsychiatric disease". Pediatric Research 86 (2): 157–164. August 2019. doi:10.1038/s41390-019-0405-9. PMID 31003234.

- ↑ Neurodevelopmental Disorders, America's Children and the Environment (3 ed.), EPA, August 2017, p. 12, https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2017-07/documents/neurodevelopmental_updates_0.pdf, retrieved 2019-07-10

Further reading

- Neurodevelopmental disorders. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. 1999. ISBN 978-0-262-20116-2.

- Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Berlin: Springer. 2006. ISBN 978-3-211-26291-7.

External links

- A Review of Neurodevelopmental Disorders – Medscape review

|

KSF

KSF