Prion

Topic: Medicine

From HandWiki - Reading time: 34 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 34 min

A prion (/ˈpriːɒn/ (![]() listen)) is a misfolded protein that induces misfolding in normal variants of the same protein, leading to cellular death. Prions are responsible for prion diseases, known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSEs), which are fatal and transmissible neurodegenerative diseases affecting both humans and animals.[1][2] These proteins can misfold sporadically, due to genetic mutations, or by exposure to an already misfolded protein, leading to an abnormal three-dimensional structure that can propagate misfolding in other proteins.[3]

listen)) is a misfolded protein that induces misfolding in normal variants of the same protein, leading to cellular death. Prions are responsible for prion diseases, known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSEs), which are fatal and transmissible neurodegenerative diseases affecting both humans and animals.[1][2] These proteins can misfold sporadically, due to genetic mutations, or by exposure to an already misfolded protein, leading to an abnormal three-dimensional structure that can propagate misfolding in other proteins.[3]

The term prion comes from "proteinaceous infectious particle".[4][5] Unlike other infectious agents such as viruses, bacteria, and fungi, prions do not contain nucleic acids (DNA or RNA). Prions are mainly twisted isoforms of the major prion protein (PrP), a naturally occurring protein with an uncertain function. They are the hypothesized cause of various TSEs, including scrapie in sheep, chronic wasting disease (CWD) in deer, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in cattle (mad cow disease), and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) in humans.[6]

All known prion diseases in mammals affect the structure of the brain or other neural tissues. These diseases are progressive, have no known effective treatment, and are invariably fatal.[7] Most prion diseases were thought to be caused by PrP until 2015 when a prion form of alpha-synuclein was linked to multiple system atrophy (MSA).[8] Misfolded proteins are also linked to other neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), which have been shown to originate and progress by a prion-like mechanism.[9][10][11]

Prions are a type of intrinsically disordered protein that continuously changes conformation unless bound to a specific partner, such as another protein. Once a prion binds to another in the same conformation, it stabilizes and can form a fibril, leading to abnormal protein aggregates called amyloids. These amyloids accumulate in infected tissue, causing damage and cell death.[12] The structural stability of prions makes them resistant to denaturation by chemical or physical agents, complicating disposal and containment, and raising concerns about iatrogenic spread through medical instruments.

Etymology and pronunciation

The word prion, coined in 1982 by Stanley B. Prusiner, is derived from protein and infection, hence prion.[13] It is short for "proteinaceous infectious particle",[8] in reference to its ability to self-propagate and transmit its conformation to other proteins.[14] Its main pronunciation is /ˈpriːɒn/ (![]() listen),[15][16][17] although /ˈpraɪɒn/, as the homographic name of the bird (prions or whalebirds) is pronounced,[17] is also heard.[18] In his 1982 paper introducing the term, Prusiner specified that it is "pronounced pree-on".[13]

listen),[15][16][17] although /ˈpraɪɒn/, as the homographic name of the bird (prions or whalebirds) is pronounced,[17] is also heard.[18] In his 1982 paper introducing the term, Prusiner specified that it is "pronounced pree-on".[13]

Prion protein

Structure

Prions consist of a misfolded form of major prion protein (PrP), a protein that is a natural part of the bodies of humans and other animals. The PrP found in infectious prions has a different structure and is resistant to proteases, the enzymes in the body that can normally break down proteins. The normal form of the protein is called PrPC, while the infectious form is called PrPSc – the C refers to 'cellular' PrP, while the Sc refers to 'scrapie', the prototypic prion disease, occurring in sheep.[19] PrP can also be induced to fold into other more-or-less well-defined isoforms in vitro; although their relationships to the form(s) that are pathogenic in vivo is often unclear, high-resolution structural analyses have begun to reveal structural features that correlate with prion infectivity.[20]

PrPC

PrPC is a normal protein found on the membranes of cells, "including several blood components of which platelets constitute the largest reservoir in humans".[21] It has 209 amino acids (in humans), one disulfide bond, a molecular mass of 35–36 kDa and a mainly alpha-helical structure.[22][23] Several topological forms exist; one cell surface form that is anchored via glycolipid, and two transmembrane forms.[24] The normal protein is not sedimentable; meaning that it cannot be separated by centrifuging techniques.[25] It has a complex function, which continues to be investigated. PrPC binds copper(II) ions (those in a +2 oxidation state) with high affinity.[26] This property is supposed to play a role in PrPC's anti-oxidative properties via reversible oxidation of the N-terminal's methionine residues into sulfoxide.[27] Moreover, studies have suggested that, in vivo, due to PrPC's low selectivity to metallic substrates, the protein's anti oxidative function is impaired when in contact with metals other than copper.[28] PrPC is readily digested by proteinase K and can be liberated from the cell surface by the enzyme phosphoinositide phospholipase C (PI-PLC), which cleaves the glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI) glycolipid anchor.[29] PrP plays an important role in cell-cell adhesion and intracellular signaling in vivo,[30] and may therefore be involved in cell-cell communication in the brain.[31]

PrPSc

The infectious isoform of PrP, known as PrPSc, or simply the prion, is able to convert normal PrPC proteins into the infectious isoform by changing their conformation, or shape; this, in turn, alters the way the proteins interact. PrPSc always causes prion disease. PrPSc has a higher proportion of β-sheet structure in place of the normal α-helix structure.[32][33][34] Several highly infectious, brain-derived PrPSc structures have been discovered by cryo-electron microscopy.[35][36][37] Another brain-derived fibril structure isolated from humans with Gerstmann-Straussler-Schienker syndrome has also been determined.[38] All of the structures described in high resolution so far are amyloid fibers in which individual PrP molecules are stacked via intermolecular beta sheets. However, 2-D crystalline arrays have also been reported at lower resolution in ex vivo preparations of prions.[39] In the prion amyloids, the glycolipid anchors and asparagine-linked glycans, when present, project outward from the lateral surfaces of the fiber cores. Often PrPSc is bound to cellular membranes, presumably via its array of glycolipid anchors, however, sometimes the fibers are dissociated from membranes and accumulate outside of cells in the form of plaques. The end of each fiber acts as a template onto which free protein molecules may attach, allowing the fiber to grow. This growth process requires complete refolding of PrPC.[35] Different prion strains have distinct templates, or conformations, even when composed of PrP molecules of the same amino acid sequence, as occurs in a particular host genotype.[40][41][42][43][44] Under most circumstances, only PrP molecules with an identical amino acid sequence to the infectious PrPSc are incorporated into the growing fiber.[25] However, cross-species transmission also happens rarely.[45]

PrPres

Protease-resistant PrPSc-like protein (PrPres) is the name given to any isoform of PrPc that is structurally altered and converted into a misfolded proteinase K-resistant form.[46] To model conversion of PrPC to PrPSc in vitro, Kocisko et al. showed that PrPSc could cause PrPC to convert to PrPres under cell-free conditions,[47] and Soto et al. demonstrated sustained amplification of PrPres and prion infectivity by a procedure involving cyclic amplification of protein misfolding.[48] The term "PrPres" may refer either to protease-resistant forms of PrPSc, which is isolated from infectious tissue and associated with the transmissible spongiform encephalopathy agent, or to other protease-resistant forms of PrP that, for example, might be generated in vitro.[49] Accordingly, unlike PrPSc, PrPres may not necessarily be infectious.

Normal function of PrP

The physiological function of the prion protein remains poorly understood. While data from in vitro experiments suggest many dissimilar roles, studies on PrP knockout mice have provided only limited information because these animals exhibit only minor abnormalities. Research in mice has found that the cleavage of PrP in peripheral nerves causes the activation of myelin repair in Schwann cells, and that the lack of PrP proteins causes demyelination in those cells.[50]

PrP and regulated cell death

MAVS, RIP1, and RIP3 are prion-like proteins found in other parts of the body. They also polymerise into filamentous amyloid fibers that initiate regulated cell death in the case of a viral infection to prevent the spread of virions to other, surrounding cells.[51] There is evidence that PrP and pathogenic PrPSc contribute to ferroptosis sensitivity, a condition that is enhanced by RAC3 expression [52].

PrP and long-term memory

A review of evidence in 2005 suggested that PrP may have a normal function in the maintenance of long-term memory.[53] As well, a 2004 study found that mice lacking genes for normal cellular PrP protein show altered hippocampal long-term potentiation.[54][55] A recent study that also suggests why this might be the case, found that neuronal protein CPEB has a similar genetic sequence to yeast prion proteins. The prion-like formation of CPEB is essential for maintaining long-term synaptic changes associated with long-term memory formation.[56]

PrP and stem cell renewal

A 2006 article from the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research indicates that PrP expression on stem cells is necessary for an organism's self-renewal of bone marrow. The study showed that all long-term hematopoietic stem cells express PrP on their cell membrane and that hematopoietic tissues with PrP-null stem cells exhibit increased sensitivity to cell depletion.[57]

PrP and innate immunity

There is some evidence that PrP may play a role in innate immunity, as the expression of PRNP, the PrP gene, is upregulated in many viral infections and PrP has antiviral properties against many viruses, including HIV.[58]

Replication

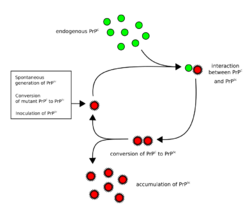

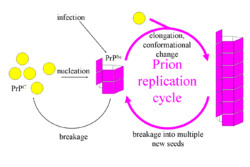

The first hypothesis that tried to explain how prions replicate in a protein-only manner was the heterodimer model.[59] This model assumed that a single PrPSc molecule binds to a single PrPC molecule and catalyzes its conversion into PrPSc. The two PrPSc molecules then come apart and can go on to convert more PrPC. However, a model of prion replication must explain both how prions propagate, and why their spontaneous appearance is so rare. Manfred Eigen showed that the heterodimer model requires PrPSc to be an extraordinarily effective catalyst, increasing the rate of the conversion reaction by a factor of around 1015.[60] This problem does not arise if PrPSc exists only in aggregated forms such as amyloid, where cooperativity may act as a barrier to spontaneous conversion. What is more, despite considerable effort, infectious monomeric PrPSc has never been isolated.[61]

An alternative model assumes that PrPSc exists only as fibrils, and that fibril ends bind PrPC and convert it into PrPSc. If this were all, then the quantity of prions would increase linearly, forming ever longer fibrils. But exponential growth of both PrPSc and the quantity of infectious particles is observed during prion disease.[62][63][64] This can be explained by taking into account fibril breakage.[65] A mathematical solution for the exponential growth rate resulting from the combination of fibril growth and fibril breakage has been found.[66] The exponential growth rate depends largely on the square root of the PrPC concentration.[66] The incubation period is determined by the exponential growth rate, and in vivo data on prion diseases in transgenic mice match this prediction.[66] The same square root dependence is also seen in vitro in experiments with a variety of different amyloid proteins.[67]

The mechanism of prion replication has implications for designing drugs. Since the incubation period of prion diseases is so long, an effective drug does not need to eliminate all prions, but simply needs to slow down the rate of exponential growth. Models predict that the most effective way to achieve this, using a drug with the lowest possible dose, is to find a drug that binds to fibril ends and blocks them from growing any further.[68]

Researchers at Dartmouth College discovered that endogenous host cofactor molecules such as the phospholipid molecule (e.g. phosphatidylethanolamine) and polyanions (e.g. single stranded RNA molecules) are necessary to form PrPSc molecules with high levels of specific infectivity in vitro, whereas protein-only PrPSc molecules appear to lack significant levels of biological infectivity.[69][70]

Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies

| Affected animal(s) | Disease |

|---|---|

| Sheep, goat | Scrapie[71] |

| Cattle | Bovine spongiform encephalopathy[71] |

| Camel[72] | Camel spongiform encephalopathy (CSE) |

| Mink[71] | Transmissible mink encephalopathy (TME) |

| White-tailed deer, elk, mule deer, moose[71] | Chronic wasting disease (CWD) |

| Cat[71] | Feline spongiform encephalopathy (FSE) |

| Nyala, oryx, greater kudu[71] | Exotic ungulate encephalopathy (EUE) |

| Ostrich[73] | Spongiform encephalopathy (unknown whether transmissible) |

| Human | Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD)[71] |

| Iatrogenic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (iCJD) | |

| Variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD) | |

| Familial Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (fCJD) | |

| Sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (sCJD) | |

| Gerstmann–Sträussler–Scheinker syndrome (GSS)[71] | |

| Fatal insomnia (FFI)[74] | |

| Kuru[71] | |

| Familial spongiform encephalopathy[75] | |

| Variably protease-sensitive prionopathy (VPSPr) |

Prions cause neurodegenerative disease by aggregating extracellularly within the central nervous system to form plaques known as amyloids, which disrupt the normal tissue structure. This disruption is characterized by "holes" in the tissue with resultant spongy architecture due to the vacuole formation in the neurons.[76] Other histological changes include astrogliosis and the absence of an inflammatory reaction.[77] While the incubation period for human prion diseases is relatively long (5 to 20 years or more), once symptoms appear the disease progresses rapidly, leading to brain damage and death.[78][79] Neurodegenerative symptoms can include convulsions, dementia, ataxia (balance and coordination dysfunction), and behavioural or personality changes.[80][81]

Many different mammalian species can be affected by prion diseases, as the prion protein (PrP) is very similar in all mammals.[82] Due to small differences in PrP between different species it is unusual for a prion disease to transmit from one species to another. The human prion disease variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, however, is thought to be caused by a prion that typically infects cattle (causing bovine spongiform encephalopathy) and that is transmitted through infected meat.[83]

All known prion diseases are untreatable and fatal.[7][84][85]

Until 2015 all known mammalian prion diseases were considered to be caused by the prion protein, PrP. After 2015 this remains true for diseases in the category of "transmissible spongiform encephalopathy" (TSE), which is transmissible and causes a specific sponge-like appearance of infected brain tissue. The endogenous, properly folded form of the prion protein is denoted PrPC (for Common or Cellular), whereas the disease-linked, misfolded form is denoted PrPSc (for Scrapie), after one of the diseases first linked to prions and neurodegeneration.[25][11] The precise structure of the prion is not known, though they can be formed spontaneously by combining PrPC, homopolymeric polyadenylic acid, and lipids in a protein misfolding cyclic amplification (PMCA) reaction even in the absence of pre-existing infectious prions.[69] This result is further evidence that prion replication does not require genetic information.[86]

Transmission

Prion diseases can arise in three different ways: acquired, familial, or sporadic.[87] It is often assumed that the disease-related form (PrPSc) directly interacts with the normal form (PrPC) to make it rearrange its structure. One idea, the "Protein X" hypothesis, is that an as-yet unidentified cellular protein (Protein X) enables the conversion of PrPC to PrPSc by bringing a molecule of each of the two together into a complex.[88]

The primary method of prion infection in animals is through ingestion of PrPSc. It is thought that prions may be deposited in the environment through the remains of dead animals and via urine, saliva, and other body fluids. They may then linger in the soil by binding to clay and other minerals.[89]

A University of California research team has provided evidence that infection can occur from prions in feces.[90] Since animal excrement is present in many areas surrounding water reservoirs, and manure is used to fertilize many crop fields, this raises the possibility of widespread transmission. Preliminary evidence suggesting that prions might be transmitted through the use of urine-derived human menopausal gonadotropin, administered for the treatment of infertility, was published in 2011.[91]

Genetic susceptibility

The majority of human prion diseases are classified as sporadic (idiopathic) Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (sCJD). Genetic research has identified an association between susceptibility to sCJD and a polymorphism at codon 129 in the PRNP gene, which encodes the prion protein (PrP). A homozygous methionine/methionine (MM) genotype at this position has been shown to significantly increase the risk of developing sCJD when compared to a heterozygous methionine/valine (MV) genotype. Analysis of multiple studies has shown that individuals with the MM genotype are approximately five times more likely to develop sCJD than those with the MV genotype.[92]

Prions in plants

In 2015, researchers at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston found that plants can be a vector for prions. When researchers fed hamsters grass that grew on ground where a deer that died with chronic wasting disease (CWD) was buried, the hamsters became ill with CWD. The findings suggest that prions can be taken up by plants that are eaten by herbivores, thus completing the cycle. It is thus possible that there is a progressively accumulating number of prions in the environment.[93][94]

Sterilization

Infectious agents possessing nucleic acids are dependent upon DNA or RNA to direct their continued replication. Prions, however, derive their infectivity from their ability to transform normal PrP to PrPSc, the misshapen, disease causing conformation. Inactivating prions via sterilization, therefore, requires the denaturation of the protein to a state in which the molecule is no longer able to induce the abnormal folding of normal PrP. In general, prions are resistant to proteases, heat, ionizing radiation, and formaldehyde treatments,[95] although their infectivity can be reduced by such treatments. Effective prion decontamination relies upon protein hydrolysis or reduction or destruction of protein tertiary structure. Examples of such sterilization agents include sodium hypochlorite, sodium hydroxide, and strongly acidic detergents such as LpH.[96]

The World Health Organization recommends any of the following three procedures for the sterilization of all heat-resistant surgical instruments to ensure that they are not contaminated with prions:

- Immerse in 1N sodium hydroxide and place in a gravity-displacement autoclave at 121 °C for 30 minutes; clean; rinse in water; and then perform routine sterilization processes.

- Immerse in 1N sodium hypochlorite (20,000 parts per million available chlorine) for 1 hour; transfer instruments to water; heat in a gravity-displacement autoclave at 121 °C for 1 hour; clean; and then perform routine sterilization processes.

- Immerse in 1N sodium hydroxide or sodium hypochlorite (20,000 parts per million available chlorine) for 1 hour; remove and rinse in water, then transfer to an open pan and heat in a gravity-displacement (121 °C) or in a porous-load (134 °C) autoclave for 1 hour; clean; and then perform routine sterilization processes.[97]

Heating at 134 °C (273 °F) for 18 minutes in a pressurized steam autoclave has been found to be somewhat effective in deactivating prions.[98][99] Ozone sterilization has been studied as a potential method for prion denaturation and deactivation.[100] Other approaches being developed include thiourea-urea treatment, guanidinium chloride treatment,[101] and special heat-resistant subtilisin combined with heat and detergent.[102] A number of decontamination reagents have been commercially manufactured with significant differences in efficacy among methods.[103] A method sufficient for sterilizing prions on one material may fail on another.[104]

Renaturation of a completely denatured prion to infectious status has not yet been achieved; however, partially denatured prions can be renatured to an infective status under certain artificial conditions.[105]

Degradation resistance in nature

Overwhelming evidence shows that prions resist degradation and persist in the environment for years, and that proteases do not degrade them. Experimental evidence shows that unbound prions degrade over time, while soil-bound prions remain at stable or increasing levels, suggesting that prions likely accumulate in the environment.[106][107] One 2015 study by US scientists found that repeated drying and wetting may render soil bound prions less infectious, although this was dependent on the soil type they were bound to.[108]

Degradation by living beings

Recent studies suggest that scrapie prions can be degraded by diverse cellular mechanisms in the affected animal cell. In an infected cell, extracellular lysosomal PrPSc does not tend to accumulate and is rapidly cleared by the lysosome via the endosome. The intracellular portion is harder to clear and tends to build up. The ubiquitin proteasome system appears to be able to degrade aggregates if they are small enough. Autophagy plays a bigger role by accepting PrPSc from the ER lumen and degrading it. Altogether these mechanisms allow the cell to delay its death from being overwhelmed by misfolded proteins.[109] Inhibition of autophagy accelerates prion accumulation whereas encouragement of autophagy promotes prion clearance. Some autophagy-promoting compounds have shown promise in animal models by delaying disease onset and death.[109]

In addition, keratinase from B. licheniformis,[110][111] alkaline serine protease from Streptomyces sp,[112] subtilisin-like pernisine from Aeropyrum pernix,[113] alkaline protease from Nocardiopsis sp,[114] nattokinase from B. subtilis,[115] engineered subtilisins from B. lentus[116][117] and serine protease from three lichen species[118] have been found to degrade PrPSc.

Fungi

Proteins showing prion-type behavior are also found in some fungi, which has been useful in helping to understand mammalian prions. Fungal prions do not always cause disease in their hosts.[119] In yeast, protein refolding to the prion configuration is assisted by chaperone proteins such as Hsp104.[120] All known prions induce the formation of an amyloid fold, in which the protein polymerises into an aggregate consisting of tightly packed beta sheets. Amyloid aggregates are fibrils, growing at their ends, and they replicate when breakage causes two growing ends to become four growing ends. The incubation period of prion diseases is determined by the exponential growth rate associated with prion replication, which is a balance between the linear growth and the breakage of aggregates.[66]

Fungal proteins that exhibit templated structural change were discovered in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae by Reed Wickner in the early 1990s. For their mechanistic similarity to mammalian prions, they were termed yeast prions. Subsequent to this, a prion has also been found in the fungus Podospora anserina. These prions behave similarly to PrP, but, in general, are nontoxic to their hosts. Susan Lindquist's group at the Whitehead Institute has argued that some fungal prions are not associated with any disease state, but they may have a useful role; however, researchers at the NIH have also provided arguments suggesting that fungal prions could be considered a diseased state.[121] There is evidence that fungal prions have evolved specific functions that are beneficial to the microorganism that enhance their ability to adapt to their diverse environments.[122] Further, within yeasts, prions can act as vectors of epigenetic inheritance, transferring traits to offspring without any genomic change.[123][124]

| Protein | Natural host | Normal function | Prion state | Prion phenotype | Year identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ure2p | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Nitrogen catabolite repressor | [URE3] | Growth on poor nitrogen sources | 1994 |

| Sup35p | S. cerevisiae | Translation termination factor | [PSI+] | Increased levels of nonsense suppression | 1994 |

| HET-S | Podospora anserina | Regulates heterokaryon incompatibility | [Het-s] | Heterokaryon formation between incompatible strains | |

| Rnq1p | S. cerevisiae | Protein template factor | [RNQ+], [PIN+] | Promotes aggregation of other prions | |

| Swi1 | S. cerevisiae | Chromatin remodeling | [SWI+] | Poor growth on some carbon sources | 2008 |

| Cyc8 | S. cerevisiae | Transcriptional repressor | [OCT+] | Transcriptional derepression of multiple genes | 2009 |

| Mot3 | S. cerevisiae | Nuclear transcription factor | [MOT3+] | Transcriptional derepression of anaerobic genes | 2009 |

| Sfp1 | S. cerevisiae | Putative transcription factor | [ISP+] | Antisuppression | 2010[125][contradictory] |

Treatments

There are no effective treatments for prion diseases as of 2018.[126] Clinical trials in humans have not met with success and have been hampered by the rarity of prion diseases.[126]

Many possible treatments work in the test-tube but not in lab animals. One treatment that prolongs the incubation period in lab mice has failed in human patients diagnosed with definite or probable vCJD. Another treatment that works in mice was tried in 6 human patients, all of whom died, before it went out of stock.[127] There was no significant increase in lifespan, but autopsy suggests that the drug was safe and reached "encouraging" concentrations in the brain and cerebrospinal fluid.[128]

While there is no known way to extend the life of a patient with prion disease, some drugs can be prescribed to control specific symptoms of the disease and accommodations can be given to improve quality of life.[127]

In other diseases

Prion-like domains have been found in a variety of other mammalian proteins. Some of these proteins have been implicated in the ontogeny of age-related neurodegenerative disorders such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive inclusions (FTLD-U), Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and Huntington's disease.[9][10][129][130] They are also implicated in some forms of systemic amyloidosis including AA amyloidosis that develops in humans and animals with inflammatory and infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, Crohn's disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and HIV/AIDS. AA amyloidosis, like prion disease, may be transmissible.[131] The involvement of abnormal proteins in all of these diseases has given rise to the 'prion paradigm', where otherwise harmless proteins can be converted to a pathogenic form by a small number of misfolded, nucleating proteins.[132]

The definition of a prion-like domain arises from the study of fungal prions. In yeast, prionogenic proteins have a portable prion domain that is both necessary and sufficient for self-templating and protein aggregation. This has been shown by attaching the prion domain to a reporter protein, which then aggregates like a known prion. Similarly, removing the prion domain from a fungal prion protein inhibits prionogenesis. This modular view of prion behaviour has led to the hypothesis that similar prion domains are present in animal proteins, in addition to PrP.[129] These fungal prion domains have several characteristic sequence features. They are typically enriched in asparagine, glutamine, tyrosine and glycine residues, with an asparagine bias being particularly conducive to the aggregative property of prions. Historically, prionogenesis has been seen as independent of sequence and only dependent on relative residue content. However, this has been shown to be false, with the spacing of prolines and charged residues having been shown to be critical in amyloid formation.[133]

Bioinformatic screens have predicted that over 250 human proteins contain prion-like domains (PrLD). These domains are hypothesized to have the same transmissible, amyloidogenic properties of PrP and known fungal proteins. As in yeast, proteins involved in gene expression and RNA binding seem to be particularly enriched in PrLD's, compared to other classes of protein. In particular, 29 of the known 210 proteins with an RNA recognition motif also have a putative prion domain. Meanwhile, several of these RNA-binding proteins have been independently identified as pathogenic in cases of ALS, FTLD-U, Alzheimer's disease, and Huntington's disease.[134]

Role in neurodegenerative disease

The pathogenicity of prions and proteins with prion-like domains is hypothesized to arise from their self-templating ability and the resulting exponential growth of amyloid fibrils. The presence of amyloid fibrils in patients with degenerative diseases has been well documented. These amyloid fibrils are seen as the result of pathogenic proteins that self-propagate and form highly stable, non-functional aggregates.[134] While this does not necessarily imply a causal relationship between amyloid and degenerative diseases, the toxicity of certain amyloid forms and the overproduction of amyloid in familial cases of degenerative disorders supports the idea that amyloid formation is generally toxic.[135]

TDP-43

Specifically, aggregation of TDP-43, an RNA-binding protein, has been found in ALS/MND patients, and mutations in the genes coding for these proteins have been identified in familial cases of ALS/MND. These mutations promote the misfolding of the proteins into a prion-like conformation. The misfolded form of TDP-43 forms cytoplasmic inclusions in affected neurons, and is found depleted in the nucleus. In addition to ALS/MND and FTLD-U, TDP-43 pathology is a feature of many cases of Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease and Huntington's disease. The misfolding of TDP-43 is largely directed by its prion-like domain. This domain is inherently prone to misfolding, while pathological mutations in TDP-43 have been found to increase this propensity to misfold, explaining the presence of these mutations in familial cases of ALS/MND. As in yeast, the prion-like domain of TDP-43 has been shown to be both necessary and sufficient for protein misfolding and aggregation.[129]

RNPA2B1, RNPA1

Similarly, pathogenic mutations have been identified in the prion-like domains of heterogeneous nuclear riboproteins hnRNPA2B1 and hnRNPA1 in familial cases of muscle, brain, bone and motor neuron degeneration. The wild-type form of all of these proteins show a tendency to self-assemble into amyloid fibrils, while the pathogenic mutations exacerbate this behaviour and lead to excess accumulation.[136]

Aβ

Alzheimer's disease is a form of dementia that is characterized by the buildup of two abnormal proteins in the brain: Aβ protein in Aβ plaques and tau protein in neurofibrillary tangles.[137] Cumulative evidence indicates that abnormalities of Abeta are the earliest pathologic sign of Alzheimer's.[137] In experimental animals, scientists found that Aβ can be induced to aggregate to form Aβ plaques and cerebral amyloid angiopathy by a mechanism that is similar to that underlying prion diseases.[132][138][139] Under highly unusual circumstances, Aβ deposition also can be stimulated in humans by the iatrogenic introduction of abeta 'seeds' (sometimes referred to as 'Aβ prions'[138]) into the body. Specifically, researchers analyzed people who had been treated with biological materials (such as growth hormone or dura mater patches) that had been collected from deceased human donors; they found that some of the recipients developed prion disease, but also that some of them had Aβ plaques and cerebral amyloid angiopathy in the brain.[140][141] This finding suggests that some batches of the biologic agents were contaminated with Aβ seeds, probably because some of the donors had Alzheimer's disease at the time of death. When a very long time had passed following exposure to the contaminated biologic material (30 years or more), some of the affected individuals showed other signs of Alzheimer's disease, including tauopathy.[142][143] Researchers emphasize that Alzheimer's is not a contagious disease; rather, the findings in humans support the theory that abnormal Aβ initiates Alzheimer's disease by a 'prion-like' mechanism that originates within the body.[144]

Alpha-synuclein

Both multiple system atrophy (MSA) and Parkinson's disease (PD) are associated with misfolded alpha-synuclein. In 2015, it was found that mice engineered to have a susceptible human version of alpha-synuclein become sick with MSA when injected in the brain with the brain homogenate of human MSA patients, but they do not get PD when injected with the brain homogenate of human PD patients. This suggests that the two diseases are different, with MSA being more transmissible.[8] Misfolded alpha-synuclein from either Parkinson's disease or MSA can be detected by protein misfolding cyclic amplification (PMCA). The two forms, after PMCA, show different levels of fluorescence when bound to thioflavin T. This allows for distinguishing between the two diseases.[145]

Weaponization

Prions could theoretically be employed as a weaponized agent.[146][147] With potential fatality rates of 100%, prions could be an effective bioweapon, sometimes called a "biochemical weapon", because a prion is a biochemical. An unfavorable aspect is prions' very long incubation periods. Persistent heavy exposure of prions to the intestine might shorten the overall onset.[148] Another negative aspect of using prions in warfare is the difficulty of detection and decontamination.[149]

History

In the 18th and 19th centuries, exportation of sheep from Spain was observed to coincide with a disease called scrapie. This disease caused the affected animals to "lie down, bite at their feet and legs, rub their backs against posts, fail to thrive, stop feeding and finally become lame".[150] The disease was also observed to have the long incubation period that is a key characteristic of transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs). Although the cause of scrapie was not known back then, it is probably the first transmissible spongiform encephalopathy to be recorded.[151]

In the 1950s, Carleton Gajdusek began research which eventually showed that kuru could be transmitted to chimpanzees by what was possibly a new infectious agent, work for which he eventually won the 1976 Nobel Prize. During the 1960s, two London-based researchers, radiation biologist Tikvah Alper and biophysicist John Stanley Griffith, developed the hypothesis that the transmissible spongiform encephalopathies are caused by an infectious agent consisting solely of proteins.[152][153] Earlier investigations by E.J. Field into scrapie and kuru had found evidence for the transfer of pathologically inert polysaccharides that only become infectious post-transfer, in the new host.[154][155] Alper and Griffith wanted to account for the discovery that the mysterious infectious agent causing the diseases scrapie and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease resisted ionizing radiation.[156] Griffith proposed three ways in which a protein could be a pathogen:[153]

In the first hypothesis, he suggested that if the protein is the product of a normally suppressed gene, and introducing the protein could induce the gene's expression, that is, wake the dormant gene up, then the result would be a process indistinguishable from replication, as the gene's expression would produce the protein, which would then wake the gene in other cells.[153]

His second hypothesis forms the basis of the modern prion theory, and proposed that an abnormal form of a cellular protein can convert normal proteins of the same type into its abnormal form, thus leading to replication.[153]

His third hypothesis proposed that the agent could be an antibody if the antibody was its own target antigen, as such an antibody would result in more and more antibody being produced against itself.[153] However, Griffith acknowledged that this third hypothesis was unlikely to be true due to the lack of a detectable immune response.[157]

Francis Crick recognized the potential significance of the Griffith protein-only hypothesis for scrapie propagation in the second edition of his "Central dogma of molecular biology" (1970): While asserting that the flow of sequence information from protein to protein, or from protein to RNA and DNA was "precluded", he noted that Griffith's hypothesis was a potential contradiction (although it was not so promoted by Griffith).[158] The central dogma was later revised, in part, to accommodate reverse transcription (which both Howard Temin and David Baltimore discovered in 1970).[159]

In 1982, Stanley B. Prusiner of the University of California, San Francisco, announced that his team had purified the hypothetical infectious protein, which did not appear to be present in healthy hosts, though they did not manage to isolate the protein until two years after Prusiner's announcement.[160][13] The protein was named a prion, for "proteinacious infectious particle", derived from the words protein and infection. When the prion was discovered, Griffith's first hypothesis, that the protein was the product of a normally silent gene, was favored by many. It was subsequently discovered, however, that the same protein exists in normal hosts but in different form.[161]

Following the discovery of the same protein in different form in uninfected individuals, the specific protein that the prion was composed of was named the prion protein (PrP), and Griffith's second hypothesis, that an abnormal form of a host protein can convert other proteins of the same type into its abnormal form, became the dominant theory.[157] Prusiner was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1997 for his research into prions.[162][163]

See also

- Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE)

- Diseases of abnormal polymerization

- Mad cow crisis

- Prion pseudoknot

- Subviral agents

- Tau protein

- Beta amyloid

- Proteinopathy

- Non-cellular life

References

- ↑ "Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies" (in en). https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/transmissible-spongiform-encephalopathies.

- ↑ "Prion diseases". National Institute of Health. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/prion-diseases.

- ↑ Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease (10th ed.). 2021.

- ↑ "What Is a Prion?". Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/what-is-a-prion-specifica/. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ↑ "Encyclopaedia Britannica". Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/prion-infectious-agent. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ↑ "Molecular biology of prion diseases". Science 252 (5012): 1515–22. June 1991. doi:10.1126/science.1675487. PMID 1675487. Bibcode: 1991Sci...252.1515P.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Prions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 95 (23): 13363–83. November 1998. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.23.13363. PMID 9811807. Bibcode: 1998PNAS...9513363P.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "Evidence for α-synuclein prions causing multiple system atrophy in humans with parkinsonism". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112 (38): E5308–17. September 2015. doi:10.1073/pnas.1514475112. PMID 26324905. Bibcode: 2015PNAS..112E5308P.

Lay summary: "A Red Flag for a Neurodegenerative Disease That May Be Transmissible". September 1, 2015. http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/a-red-flag-for-a-neurodegenerative-disease-that-may-be-transmissible/. - ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Neurodegenerative diseases: Expanding the prion concept". Annual Review of Neuroscience 38: 87–103. 2015. doi:10.1146/annurev-neuro-071714-033828. PMID 25840008.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Parkinson's disease and alpha synuclein: is Parkinson's disease a prion-like disorder?". Movement Disorders 28 (1): 31–40. January 2013. doi:10.1002/mds.25373. PMID 23390095.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Cellular prion protein mediates impairment of synaptic plasticity by amyloid-beta oligomers". Nature 457 (7233): 1128–32. February 2009. doi:10.1038/nature07761. PMID 19242475. Bibcode: 2009Natur.457.1128L.

- ↑ "The structural basis of protein folding and its links with human disease". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 356 (1406): 133–145. February 2001. doi:10.1098/rstb.2000.0758. PMID 11260793.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 "Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie". Science 216 (4542): 136–144. April 1982. doi:10.1126/science.6801762. PMID 6801762. Bibcode: 1982Sci...216..136P. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/f292/b22e2675419c6392a5e55f6b35b1dfc46917.pdf.

- ↑ "Stanley B. Prusiner – Autobiography". NobelPrize.org. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1997/prusiner-autobio.html.

- ↑ "Etymologia: prion". Emerging Infectious Diseases 18 (6): 1030–1. June 2012. doi:10.3201/eid1806.120271. PMID 22607731.

- ↑ "Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary". Elsevier. http://dorlands.com/.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Merriam-Webster's Unabridged Dictionary". Merriam-Webster. http://unabridged.merriam-webster.com/unabridged/.

- ↑ "The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language". Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. https://ahdictionary.com/.

- ↑ "Biomedicine. A view from the top--prion diseases from 10,000 feet". Science 300 (5621): 917–9. May 2003. doi:10.1126/science.1085920. PMID 12738843. https://zenodo.org/record/1230830. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

- ↑ "Structural biology of ex vivo mammalian prions". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 298 (8). August 2022. doi:10.1016/j.jbc.2022.102181. PMID 35752366.

- ↑ "Cellular prion protein is released on exosomes from activated platelets". Blood 107 (10): 3907–11. May 2006. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-02-0802. PMID 16434486.

- ↑ "NMR characterization of the full-length recombinant murine prion protein, mPrP(23-231)". FEBS Letters 413 (2): 282–8. August 1997. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00920-4. PMID 9280298. Bibcode: 1997FEBSL.413..282R. https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/191727/1/S0014-5793%2897%2900920-4.pdf.

- ↑ "Structure of the recombinant full-length hamster prion protein PrP(29-231): the N terminus is highly flexible". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 94 (25): 13452–7. December 1997. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.25.13452. PMID 9391046. Bibcode: 1997PNAS...9413452D.

- ↑ "A transmembrane form of the prion protein in neurodegenerative disease". Science 279 (5352): 827–834. February 1998. doi:10.1126/science.279.5352.827. PMID 9452375. Bibcode: 1998Sci...279..827H. http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4320/9efc152784dbc7f0b9a1300d0ec9be602a2c.pdf.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 "Taking aim at the transmissible spongiform encephalopathie's infectious agents". Prions and mad cow disease. New York: Marcel Dekker. 2004. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-8247-4083-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=WjeuaHopV5UC&pg=PA6. Retrieved 2020-06-02.

- ↑ "The cellular prion protein binds copper in vivo". Nature 390 (6661): 684–7. 1997. doi:10.1038/37783. PMID 9414160. Bibcode: 1997Natur.390..684B.

- ↑ Arcos-López, Trinidad (1 March 2016). "Spectroscopic and Theoretical Study of CuI Binding to His111 in the Human Prion Protein Fragment 106–115". Organic Chemistry 2016 55 (Inorganic Chemistry 2016): 2909–22. doi:10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b02794. PMID 26930130.

- ↑ Wong, Boon-Seng (December 2001). "A Yin-Yang role for metals in prion disease". Panminerva Medica (2001) 43 (4): 283–7. PMID 11677424.

- ↑ "The state of the prion". Nature Reviews. Microbiology 2 (11): 861–871. November 2004. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1025. PMID 15494743.

- ↑ "Regulation of embryonic cell adhesion by the prion protein". PLOS Biology 7 (3): e55. March 2009. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000055. PMID 19278297.

- ↑ "Prion Protein Signaling in the Nervous System—A Review and Perspective" (in en). Signal Transduction Insights 3. 2014. doi:10.4137/STI.S12319. ISSN 1178-6434.

- ↑ "Secondary structure analysis of the scrapie-associated protein PrP 27-30 in water by infrared spectroscopy". Biochemistry 30 (31): 7672–80. August 1991. doi:10.1021/bi00245a003. PMID 1678278.

- ↑ "Conformational transitions, dissociation, and unfolding of scrapie amyloid (prion) protein". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 268 (27): 20276–84. September 1993. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(20)80725-x. PMID 8104185.

- ↑ "Conversion of alpha-helices into beta-sheets features in the formation of the scrapie prion proteins". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 90 (23): 10962–6. December 1993. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.23.10962. PMID 7902575. Bibcode: 1993PNAS...9010962P.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "High-resolution structure and strain comparison of infectious mammalian prions". Molecular Cell 81 (21): 4540–51. November 2021. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2021.08.011. PMID 34433091.

- ↑ "Cryo-EM structure of anchorless RML prion reveals variations in shared motifs between distinct strains". Nature Communications 13 (1). July 2022. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-30458-6. PMID 35831291. Bibcode: 2022NatCo..13.4005H.

- ↑ "2.7 Å cryo-EM structure of ex vivo RML prion fibrils". Nature Communications 13 (1). July 2022. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-30457-7. PMID 35831275. Bibcode: 2022NatCo..13.4004M.

- ↑ "Cryo-EM structures of prion protein filaments from Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker disease". Acta Neuropathologica 144 (3): 509–520. September 2022. doi:10.1007/s00401-022-02461-0. PMID 35819518.

- ↑ "Structural studies of the scrapie prion protein by electron crystallography". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99 (6): 3563–8. March 2002. doi:10.1073/pnas.052703499. PMID 11891310. Bibcode: 2002PNAS...99.3563W.

- ↑ "Non-genetic propagation of strain-specific properties of scrapie prion protein". Nature 375 (6533): 698–700. June 1995. doi:10.1038/375698a0. PMID 7791905. Bibcode: 1995Natur.375..698B.

- ↑ "Evidence for the conformation of the pathologic isoform of the prion protein enciphering and propagating prion diversity". Science 274 (5295): 2079–82. December 1996. doi:10.1126/science.274.5295.2079. PMID 8953038. Bibcode: 1996Sci...274.2079T.

- ↑ "Eight prion strains have PrP(Sc) molecules with different conformations". Nature Medicine 4 (10): 1157–65. October 1998. doi:10.1038/2654. PMID 9771749.

- ↑ "Cryo-EM of prion strains from the same genotype of host identifies conformational determinants". PLOS Pathogens 18 (11). November 2022. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1010947. PMID 36342968.

- ↑ "A structural basis for prion strain diversity". Nature Chemical Biology 19 (5): 607–613. May 2023. doi:10.1038/s41589-022-01229-7. PMID 36646960.

- ↑ "Cross-species transmission of CWD prions". Prion 10 (1): 83–91. 2016. doi:10.1080/19336896.2015.1118603. PMID 26809254.

- ↑ "Biochemistry and structure of PrP(C) and PrP(Sc)". British Medical Bulletin 66 (1): 21–33. June 2003. doi:10.1093/bmb/66.1.21. PMID 14522846.

- ↑ "Cell-free formation of protease-resistant prion protein". Nature 370 (6489): 471–4. August 1994. doi:10.1038/370471a0. PMID 7913989. Bibcode: 1994Natur.370..471K.

- ↑ "Sensitive detection of pathological prion protein by cyclic amplification of protein misfolding". Nature 411 (6839): 810–3. June 2001. doi:10.1038/35081095. PMID 11459061. Bibcode: 2001Natur.411..810S.

- ↑ "Autocatalytic self-propagation of misfolded prion protein". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101 (33): 12207–11. August 2004. doi:10.1073/pnas.0404650101. PMID 15297610. Bibcode: 2004PNAS..10112207B.

- ↑ "Healthy prions protect nerves". Nature. 2010-01-24. doi:10.1038/news.2010.29.

- ↑ "Necroptosis in anti-viral inflammation". Cell Death and Differentiation 26 (1): 4–13. January 2019. doi:10.1038/s41418-018-0172-x. PMID 30050058.

- ↑ Peng, Hao; Pfeiffer, Susanne; Varynskyi, Borys; Qiu, Marina; Srinark, Chanikarn; Jin, Xiang; Zhang, Xin; Williams, Katie et al. (2025-06-25). "Prion-induced ferroptosis is facilitated by RAC3" (in en). Nature Communications 16 (1): 5385. doi:10.1038/s41467-025-60793-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMID 40562790. PMC 12198409. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-60793-3.

- ↑ "Prions as adaptive conduits of memory and inheritance". Nature Reviews. Genetics 6 (6): 435–450. June 2005. doi:10.1038/nrg1616. PMID 15931169.

- ↑ "Hippocampal synaptic plasticity in mice devoid of cellular prion protein". Brain Research. Molecular Brain Research 131 (1–2): 58–64. November 2004. doi:10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.08.004. PMID 15530652.

- ↑ "PrPC controls via protein kinase A the direction of synaptic plasticity in the immature hippocampus". The Journal of Neuroscience 33 (7): 2973–83. February 2013. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4149-12.2013. PMID 23407955.

- ↑ "Long-term memory consolidation: The role of RNA-binding proteins with prion-like domains". RNA Biology 14 (5): 568–586. May 2017. doi:10.1080/15476286.2016.1244588. PMID 27726526.

- ↑ "Prion protein is expressed on long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells and is important for their self-renewal". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103 (7): 2184–9. February 2006. doi:10.1073/pnas.0510577103. PMID 16467153. Bibcode: 2006PNAS..103.2184Z.

- ↑ "Prion Protein PRNP: A New Player in Innate Immunity? The Aβ Connection". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease Reports 1 (1): 263–275. December 2017. doi:10.3233/ADR-170037. PMID 30480243.

- ↑ "Structural clues to prion replication". Science 264 (5158): 530–1. April 1994. doi:10.1126/science.7909169. PMID 7909169. Bibcode: 1994Sci...264..530C.

- ↑ "Prionics or the kinetic basis of prion diseases". Biophysical Chemistry 63 (1): A1-18. December 1996. doi:10.1016/S0301-4622(96)02250-8. PMID 8981746.

- ↑ "The Structure of Mammalian Prions and Their Aggregates". International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology 329: 277–301. 2017. doi:10.1016/bs.ircmb.2016.08.013. ISBN 978-0-12-812251-8. PMID 28109330.

- ↑ "Copurification of Sp33-37 and scrapie agent from hamster brain prior to detectable histopathology and clinical disease". The Journal of General Virology 72 (12): 2905–13. December 1991. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-72-12-2905. PMID 1684986.

- ↑ "Proteinase-resistant prion protein accumulation in Syrian hamster brain correlates with regional pathology and scrapie infectivity". Neurology 41 (9): 1482–90. September 1991. doi:10.1212/WNL.41.9.1482. PMID 1679911.

- ↑ "Sequential appearance and accumulation of pathognomonic markers in the central nervous system of hamsters orally infected with scrapie". The Journal of General Virology 77 ( Pt 8) (8): 1925–34. August 1996. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-77-8-1925. PMID 8760444.

- ↑ "Prion protein structure and scrapie replication: theoretical, spectroscopic, and genetic investigations". Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology 61: 495–509. 1996. doi:10.1101/SQB.1996.061.01.050. PMID 9246476.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 66.2 66.3 "Quantifying the kinetic parameters of prion replication". Biophysical Chemistry 77 (2–3): 139–152. March 1999. doi:10.1016/S0301-4622(99)00016-2. PMID 10326247.

- ↑ "An analytical solution to the kinetics of breakable filament assembly". Science 326 (5959): 1533–7. December 2009. doi:10.1126/science.1178250. PMID 20007899. Bibcode: 2009Sci...326.1533K.

- ↑ "Designing drugs to stop the formation of prion aggregates and other amyloids". Biophysical Chemistry 88 (1–3): 47–59. December 2000. doi:10.1016/S0301-4622(00)00197-6. PMID 11152275.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 "Formation of native prions from minimal components in vitro". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104 (23): 9741–6. June 2007. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702662104. PMID 17535913.

- ↑ "Cofactor molecules maintain infectious conformation and restrict strain properties in purified prions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109 (28): E1938–E1946. July 2012. doi:10.1073/pnas.1206999109. PMID 22711839.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 71.2 71.3 71.4 71.5 71.6 71.7 71.8 "90. Prions". ICTVdB Index of Viruses. U.S. National Institutes of Health website. 2002-02-14. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ICTVdb/Ictv/fs_prion.htm.

- ↑ "Prion Disease in Dromedary Camels, Algeria". Emerging Infectious Diseases 24 (6): 1029–36. June 2018. doi:10.3201/eid2406.172007. PMID 29652245.

- ↑ "Prion Diseases: A Review; II. Prion Diseases in Man and Animals". Scientific Journal of King Faisal University (Basic and Applied Sciences) 5 (2): 139. 2004. https://apps.kfu.edu.sa/sjournal/ara/pdffiles/b526.pdf. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- ↑ "Prion protein conformation in a patient with sporadic fatal insomnia". The New England Journal of Medicine 340 (21): 1630–8. May 1999. doi:10.1056/NEJM199905273402104. PMID 10341275.

Lay summary: "BSE proteins may cause fatal insomnia". May 28, 1999. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/355297.stm. - ↑ "Familial spongiform encephalopathy associated with a novel prion protein gene mutation". Annals of Neurology 42 (2): 138–146. August 1997. doi:10.1002/ana.410420203. PMID 9266722.

- ↑ Robbins pathologic basis of disease. Philadelphia: Saunders. 1999. ISBN 0-7216-7335-X.

- ↑ "Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies in humans". Annual Review of Microbiology 53: 283–314. 1999. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.53.1.283. PMID 10547693.

- ↑ "Prion Diseases". US Centers for Disease Control. 2006-01-26. https://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/prions/.

- ↑ "A clinical study of kuru patients with long incubation periods at the end of the epidemic in Papua New Guinea". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 363 (1510): 3725–3739. 2008. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0068. PMID 18849289.

- ↑ "An overview of human prion diseases". Virology Journal 8 (1). December 2011. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-8-559. PMID 22196171.

- ↑ "The genetics of prion diseases". Genetics in Medicine 12 (4): 187–195. April 2010. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181cd7374. PMID 20216075.

- ↑ "Prion diseases of humans and animals: their causes and molecular basis". Annual Review of Neuroscience 24: 519–550. 2001. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.519. PMID 11283320. http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/650f/8f4c880880d357e5dd82236ba611065e21cc.pdf.

- ↑ "Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: risk of transmission by blood transfusion and blood therapies". Haemophilia 12 (Suppl 1): 8–15, discussion 26–28. March 2006. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2516.2006.01195.x. PMID 16445812.

- ↑ "Intracellular re-routing of prion protein prevents propagation of PrP(Sc) and delays onset of prion disease". The EMBO Journal 20 (15): 3957–66. August 2001. doi:10.1093/emboj/20.15.3957. PMID 11483499.

- ↑ "Prion Protein Biology Through the Lens of Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation". Journal of Molecular Biology 434 (1). January 2022. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2021.167368. PMID 34808226.

- ↑ "Protein Misfolding Cyclic Amplification of Infectious Prions". Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science 150: 361–374. 2017. doi:10.1016/bs.pmbts.2017.06.016. ISBN 978-0-12-811226-7. PMID 28838669.

- ↑ Prion Diseases Diagnosis and Pathogeneis. Archives of Virology. 16. New York: Springer. 2001. doi:10.1007/978-3-7091-6308-5. ISBN 978-3-211-83530-2.

- ↑ "Prion propagation in mice expressing human and chimeric PrP transgenes implicates the interaction of cellular PrP with another protein". Cell 83 (1): 79–90. October 1995. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(95)90236-8. PMID 7553876.

- ↑ "Oral transmissibility of prion disease is enhanced by binding to soil particles". PLOS Pathogens 3 (7): e93. July 2007. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0030093. PMID 17616973.

- ↑ "Asymptomatic deer excrete infectious prions in faeces". Nature 461 (7263): 529–532. September 2009. doi:10.1038/nature08289. PMID 19741608. Bibcode: 2009Natur.461..529T.

- ↑ "Detection of prion protein in urine-derived injectable fertility products by a targeted proteomic approach". PLOS ONE 6 (3). March 2011. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017815. PMID 21448279. Bibcode: 2011PLoSO...617815V.

- ↑ "The First Meta-Analysis of the M129V Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) of the Prion Protein Gene (PRNP) with Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease". Cells 10 (11): 3132. November 2021. doi:10.3390/cells10113132. PMID 34831353.

- ↑ "Surprising' Discovery Made About Chronic Wasting Disease". Food Safety News. June 1, 2015. http://www.foodsafetynews.com/2015/06/researchers-make-surprising-discovery-about-spread-of-chronic-wasting-disease/.

- ↑ "Grass plants bind, retain, uptake, and transport infectious prions". Cell Reports 11 (8): 1168–75. May 2015. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2015.04.036. PMID 25981035.

- ↑ "Doppel: more rival than double to prion". Neuroscience 141 (1): 1–8. August 2006. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.04.057. PMID 16781817.

- ↑ "Inactivation of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (prion) agents by environ LpH". Journal of Virology 78 (4): 2164–5. February 2004. doi:10.1128/JVI.78.4.2164-2165.2004. PMID 14747583.

- ↑ "Methods to minimize the risks of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease transmission by surgical procedures: where to set the standard?". Clinical Infectious Diseases 43 (6): 757–764. September 2006. doi:10.1086/507030. PMID 16912952.

- ↑ "Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies". Lancet 363 (9402): 51–61. January 2004. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15171-9. PMID 14723996.

- ↑ "New studies on the heat resistance of hamster-adapted scrapie agent: threshold survival after ashing at 600 degrees C suggests an inorganic template of replication". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 97 (7): 3418–21. March 2000. doi:10.1073/pnas.050566797. PMID 10716712. Bibcode: 2000PNAS...97.3418B.

- ↑ "Ozone Sterilization". UK Health Protection Agency. 2005-04-14. http://www.hpa.org.uk/hpa/news/articles/press_releases/2005/050414_ozone_sterilizer.htm.

- ↑ "Rapid chemical decontamination of infectious CJD and scrapie particles parallels treatments known to disrupt microbes and biofilms". Virulence 6 (8): 787–801. 2015. doi:10.1080/21505594.2015.1098804. PMID 26556670.

- ↑ "Proteolysis of abnormal prion protein with a thermostable protease from Thermococcus kodakarensis KOD1". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 98 (5): 2113–20. March 2014. doi:10.1007/s00253-013-5091-7. PMID 23880875.

- ↑ Edgeworth, JA; Sicilia, A; Linehan, J; Brandner, S; Jackson, GS; Collinge, J (March 2011). "A standardized comparison of commercially available prion decontamination reagents using the Standard Steel-Binding Assay.". The Journal of General Virology 92 (Pt 3): 718–26. doi:10.1099/vir.0.027201-0. PMID 21084494.

- ↑ "A Novel, Reliable and Highly Versatile Method to Evaluate Different Prion Decontamination Procedures". Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 8. 2020. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2020.589182. PMID 33195153.

- ↑ "Transmission of prions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99 (s 4): 16378–83. December 2002. doi:10.1073/pnas.172403799. PMID 12181490. Bibcode: 2002PNAS...9916378W.

- ↑ "The Ecology of Prions". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 81 (3). September 2017. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00001-17. PMID 28566466.

- ↑ "Soil humic acids degrade CWD prions and reduce infectivity". PLOS Pathogens 14 (11). November 2018. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1007414. PMID 30496301.

- ↑ "Mitigation of prion infectivity and conversion capacity by a simulated natural process--repeated cycles of drying and wetting". PLOS Pathogens 11 (2). February 2015. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004638. PMID 25665187.

- ↑ 109.0 109.1 "An Update on Autophagy in Prion Diseases" (in English). Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 8. 2020-08-27. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2020.00975. PMID 32984276.

- ↑ "Enzymatic degradation of prion protein in brain stem from infected cattle and sheep". The Journal of Infectious Diseases 188 (11): 1782–9. December 2003. doi:10.1086/379664. PMID 14639552.

- ↑ "Enzymatic formulation capable of degrading scrapie prion under mild digestion conditions". PLOS ONE 8 (7). 2013-07-16. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0068099. PMID 23874511. Bibcode: 2013PLoSO...868099O.

- ↑ "Alkaline serine protease produced by Streptomyces sp. degrades PrP(Sc)". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 321 (1): 45–50. August 2004. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.100. PMID 15358213.

- ↑ "Enzymatic degradation of PrPSc by a protease secreted from Aeropyrum pernix K1". PLOS ONE 7 (6). 2012. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039548. PMID 22761822. Bibcode: 2012PLoSO...739548S.

- ↑ "Degradation of PrP(Sc) by keratinolytic protease from Nocardiopsis sp. TOA-1". Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 70 (5): 1246–8. May 2006. doi:10.1271/bbb.70.1246. PMID 16717429.

- ↑ "Amyloid-degrading ability of nattokinase from Bacillus subtilis natto". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 57 (2): 503–8. January 2009. doi:10.1021/jf803072r. PMID 19117402. Bibcode: 2009JAFC...57..503H.

- ↑ "Microbial and enzymatic inactivation of prions in soil environments". Soil Biology and Biochemistry 59: 1–15. April 2013. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.12.016. ISSN 0038-0717. Bibcode: 2013SBiBi..59....1B. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0038071713000035.

- ↑ "Decontamination of prion protein (BSE301V) using a genetically engineered protease". The Journal of Hospital Infection 72 (1): 65–70. May 2009. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2008.12.007. PMID 19201054.

- ↑ "Degradation of the disease-associated prion protein by a serine protease from lichens". PLOS ONE 6 (5). May 2011. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0019836. PMID 21589935. Bibcode: 2011PLoSO...619836J.

- ↑ "Investigating protein conformation-based inheritance and disease in yeast". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 356 (1406): 169–176. February 2001. doi:10.1098/rstb.2000.0762. PMID 11260797.

- ↑ "Unraveling prion strains with cell biology and organic chemistry". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105 (1): 11–12. January 2008. doi:10.1073/pnas.0710824105. PMID 18172195. Bibcode: 2008PNAS..105...11A.

- ↑ "Probing the role of PrP repeats in conformational conversion and amyloid assembly of chimeric yeast prions". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 282 (47): 34204–12. November 2007. doi:10.1074/jbc.M704952200. PMID 17893150.

- ↑ "Blessings in disguise: biological benefits of prion-like mechanisms". Trends in Cell Biology 23 (6): 251–9. June 2013. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2013.01.007. PMID 23485338.

- ↑ "Epigenetics in the extreme: prions and the inheritance of environmentally acquired traits". Science 330 (6004): 629–632. October 2010. doi:10.1126/science.1191081. PMID 21030648. Bibcode: 2010Sci...330..629H.

- ↑ "Prions are a common mechanism for phenotypic inheritance in wild yeasts". Nature 482 (7385): 363–8. February 2012. doi:10.1038/nature10875. PMID 22337056. Bibcode: 2012Natur.482..363H.

- ↑ "Non-Mendelian determinant [ISP+ in yeast is a nuclear-residing prion form of the global transcriptional regulator Sfp1"]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107 (23): 10573–7. June 2010. doi:10.1073/pnas.1005949107. PMID 20498075. Bibcode: 2010PNAS..10710573R.

- ↑ 126.0 126.1 "Toward Therapy of Human Prion Diseases". Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology 58 (1): 331–351. January 2018. doi:10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010617-052745. PMID 28961066. https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/141186/1/Aguzzi_et_al%3B_2017_revised.pdf. Retrieved 2020-03-05.

- ↑ 127.0 127.1 "Prion Clinic – Drug treatments". 13 September 2017. http://www.prion.ucl.ac.uk/clinic-services/research/drug-treatments/.

- ↑ Mead, Simon; Khalili-Shirazi, Azadeh; Potter, Caroline; Mok, Tzehow; Nihat, Akin; Hyare, Harpreet; Canning, Stephanie; Schmidt, Christian et al. (April 2022). "Prion protein monoclonal antibody (PRN100) therapy for Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease: evaluation of a first-in-human treatment programme". The Lancet Neurology 21 (4): 342–354. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00082-5. PMID 35305340.

- ↑ 129.0 129.1 129.2 "The tip of the iceberg: RNA-binding proteins with prion-like domains in neurodegenerative disease". Brain Research 1462: 61–80. June 2012. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2012.01.016. PMID 22445064.

- ↑ "NEURODEGENERATION. Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases: The prion concept in relation to assembled Aβ, tau, and α-synuclein". Science 349 (6248). August 2015. doi:10.1126/science.1255555. PMID 26250687.

- ↑ "Transmission of systemic AA amyloidosis in animals". Veterinary Pathology 51 (2): 363–371. March 2014. doi:10.1177/0300985813511128. PMID 24280941.

- ↑ 132.0 132.1 "Self-propagation of pathogenic protein aggregates in neurodegenerative diseases". Nature 501 (7465): 45–51. September 2013. doi:10.1038/nature12481. PMID 24005412. Bibcode: 2013Natur.501...45J.

- ↑ "A systematic survey identifies prions and illuminates sequence features of prionogenic proteins". Cell 137 (1): 146–158. April 2009. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.044. PMID 19345193.

- ↑ 134.0 134.1 "The amyloid state of proteins in human diseases". Cell 148 (6): 1188–1203. March 2012. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.022. PMID 22424229.

- ↑ "Prion protein - mediator of toxicity in multiple proteinopathies". Nature Reviews. Neurology 16 (4): 187–8. April 2020. doi:10.1038/s41582-020-0332-8. PMID 32123368.

- ↑ "Mutations in prion-like domains in hnRNPA2B1 and hnRNPA1 cause multisystem proteinopathy and ALS". Nature 495 (7442): 467–473. March 2013. doi:10.1038/nature11922. PMID 23455423. Bibcode: 2013Natur.495..467K.

- ↑ 137.0 137.1 "Alzheimer Disease: An Update on Pathobiology and Treatment Strategies". Cell 179 (2): 312–339. 2019. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.09.001. PMID 31564456.

- ↑ 138.0 138.1 "β-Amyloid Prions and the Pathobiology of Alzheimer's Disease". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 8 (5). 2018. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a023507. PMID 28193770.

- ↑ "Seeds of dementia". Scientific American 308 (5): 52–57. 2013. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0513-52. PMID 23627220. Bibcode: 2013SciAm.308e..52W.

- ↑ "Evidence for human transmission of amyloid-beta pathology and cerebral amyloid angiopathy". Nature 525 (7568): 247–250. 2015. doi:10.1038/nature15369. PMID 26354483. Bibcode: 2015Natur.525..247J.

- ↑ "Dura mater is a potential source of Abeta seeds". Acta Neuropathologica 131 (6): 911–923. 2016. doi:10.1007/s00401-016-1565-x. PMID 27016065.

- ↑ "Alzheimer's disease neuropathological change three decades after iatrogenic amyloid-beta transmission". Acta Neuropathologica 142 (1): 211–215. 2021. doi:10.1007/s00401-021-02326-y. PMID 34047818.

- ↑ "Iatrogenic Alzheimer's disease in recipients of cadaveric pituitary-derived growth hormone". Nature Medicine 30 (2): 394–402. 2024. doi:10.1038/s41591-023-02729-2. PMID 38287166.

- ↑ "Evidence for iatrogenic transmission of Alzheimer's disease". Nature Medicine 30 (2): 344–345. 2024. doi:10.1038/s41591-023-02768-9. PMID 38287169.

- ↑ Shahnawaz, M; Mukherjee, A; Pritzkow, S; Mendez, N; Rabadia, P; Liu, X; Hu, B; Schmeichel, A et al. (February 2020). "Discriminating α-synuclein strains in Parkinson's disease and multiple system atrophy.". Nature 578 (7794): 273–277. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-1984-7. PMID 32025029. Bibcode: 2020Natur.578..273S.

- ↑ "What are Biological Weapons?". United Nations, Office for Disarmament Affairs. https://www.un.org/disarmament/biological-weapons/about/what-are-biological-weapons/.

- ↑ "Prions: the danger of biochemical weapons". http://www.scielo.br/pdf/cta/v34n3/01.pdf.

- ↑ "The Next Plague: Prions are Tiny, Mysterious and Frightening". American Council on Science and Health. 20 March 2017. https://www.acsh.org/news/2017/03/20/next-plague-prions-are-tiny-mysterious-and-frightening-11018.

- ↑ "Prions as Bioweapons? - Much Ado About Nothing; or Apt Concerns Over Tiny Proteins used in Biowarfare". Defence iQ. 13 September 2019. https://www.defenceiq.com/air-land-and-sea-defence-services/articles/prions-as-bioweapons.

- ↑ "How Prions Came to Be: A Brief History – Infectious Disease: Superbugs, Science, & Society" (in en-US). https://sites.duke.edu/superbugs/module-6/prions-mad-cow-disease-when-proteins-go-bad/how-prions-came-to-be-a-brief-history/.

- ↑ "Sheep scrapie and deer rabies in England prior to 1800". Prion 17 (1): 7–15. December 2023. doi:10.1080/19336896.2023.2166749. PMID 36654484.

- ↑ "Does the agent of scrapie replicate without nucleic acid?". Nature 214 (5090): 764–6. May 1967. doi:10.1038/214764a0. PMID 4963878. Bibcode: 1967Natur.214..764A.

- ↑ 153.0 153.1 153.2 153.3 153.4 "Self-replication and scrapie". Nature 215 (5105): 1043–4. September 1967. doi:10.1038/2151043a0. PMID 4964084. Bibcode: 1967Natur.215.1043G.

- ↑ "Transmission experiments with multiple sclerosis: an interim report". British Medical Journal 2 (5513): 564–5. September 1966. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5513.564. PMID 5950508.

- ↑ "The infective process in scrapie". Lancet 2 (7570): 714–6. September 1968. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(68)90754-x. PMID 4175093.

- ↑ "Susceptibility of scrapie agent to ionizing radiation". Nature. 5188 222 (5188): 90–91. April 1969. doi:10.1038/222090a0. PMID 4975649. Bibcode: 1969Natur.222...90F.

- ↑ 157.0 157.1 "Prions, the Protein Hypothesis, and Scientific Revolutions". Prions and Mad Cow Disease. Marcel Dekker. January 1, 2004. pp. 21–60. ISBN 978-0-203-91297-3. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235220355. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ↑ "Central dogma of molecular biology". Nature 227 (5258): 561–3. August 1970. doi:10.1038/227561a0. PMID 4913914. Bibcode: 1970Natur.227..561C.

- ↑ "The Discovery of Reverse Transcriptase". Annual Review of Virology 3 (1): 29–51. September 2016. doi:10.1146/annurev-virology-110615-035556. PMID 27482900.

- ↑ "The game of name is fame. But is it science?". Discover 7 (12): 28–41. December 1986.

- ↑ "Prion protein scrapie and the normal cellular prion protein". Prion 10 (1): 63–82. 2016. doi:10.1080/19336896.2015.1110293. PMID 26645475.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, 1997". NobelPrize.org. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1997/. "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1997 was awarded to Stanley B. Prusiner 'for his discovery of Prions - a new biological principle of infection'."

- ↑ "Prions Are Forever" (in en). https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/artful-amoeba/prions-are-forever/.

External links

- "Prion Diseases". US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. April 22, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/prions/index.html.[ CDC] –

- World Health Organisation – WHO information on prion diseases

- The UK BSE Inquiry – Report of the UK public inquiry into BSE and variant CJD

- UK Spongiform Encephalopathy Advisory Committee (SEAC)

- "Prion Diseases". Health: Brain, Nerves and Spine: Infectious Diseases. Johns Hopkins Medicine. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/prion-diseases.

- "Elucidating_the_Mechanism_for_Prion_Formation". https://www.researchgate.net/publication/367434365.

| Classification |

|---|

|

KSF

KSF