Progressive muscular atrophy

Topic: Medicine

From HandWiki - Reading time: 10 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 10 min

| Progressive muscular atrophy | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Duchenne–Aran disease, Duchenne–Aran muscular atrophy |

| |

| Specialty | Neurology |

Progressive muscular atrophy (PMA), also called Duchenne–Aran disease and Duchenne–Aran muscular atrophy, is a disorder characterized by the degeneration of lower motor neurons, resulting in generalized, progressive loss of muscle function.

PMA is classified among motor neuron diseases (MND) and it sporadically appears during adulthood. It is speculated that about 2.5%-11% of adult onset MND is PMA, making it less common than ALS.[1]

PMA affects only the lower motor neurons, in contrast to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), the most common MND, which affects both the upper and lower motor neurons, or primary lateral sclerosis, another MND, which affects only the upper motor neurons.

The history of PMA involved determining if it was a separate disease from ALS or if it was just the earlier stages of ALS. In the end, scientists considered PMA its own disease that was under the same category as ALS.[2] The signs and symptoms of PMA are similar to ALS but are located in a different region of the body, but the diagnosis can be more complex due to the nature of PMA and ALS. The prognosis of PMA can be longer than ALS because it affects less of the motor neurons.[3] The options for treatment are small and are still being explored, from the theory of stem cell treatment to simple physical therapy. Although there is no cure, there some possible treatments such as; physical therapy and some medications that can slow progression.

History

Despite being rarer than ALS, PMA was described earlier, when in 1850 French neurologist François Aran described 11 cases which he termed atrophie musculaire progressive. Contemporary neurologist Guillaume-Benjamin-Amand Duchenne de Boulogne English: /duːˈʃɛn/ also claimed to have described the condition 1 year earlier, although the written report was never found.[2] The condition has been called progressive muscular atrophy (PMA),[4] spinal muscular atrophy (SMA),[4] Aran–Duchenne disease,[2][4] Duchenne–Aran disease,[2] Aran–Duchenne muscular atrophy,[4] and Duchenne–Aran muscular atrophy. The name "spinal muscular atrophy" is ambiguous as it refers to any of various spinal muscular atrophies, including the autosomal recessive spinal muscular atrophy caused by a genetic defect in the SMN1 gene.[3]

Disease or syndrome

Since its initial description in 1850, there has been debate in the scientific literature over whether PMA is a distinct disease with its own characteristics, or if lies somewhere on a spectrum with ALS, PLS, and PBP. Jean-Martin Charcot, who first described ALS in 1870, felt that PMA was a separate condition, with degeneration of the lower motor neurons the most important lesion, whereas in ALS it was the upper motor neuron degeneration that was primary, with lower motor neuron degeneration being secondary. Such views still exist in archaic terms for PMA such as "Primary progressive spinal muscular atrophy". Throughout the course of the late 19th century, other conditions were discovered which had previously been thought to be PMA, such as pseudo-hypertrophic paralysis, hereditary muscular atrophy, progressive myopathy, progressive muscular dystrophy, peripheral neuritis, and syringomyelia.[2]

The neurologists Joseph Jules Dejerine and William Richard Gowers were among those who felt that PMA was part of a spectrum of motor neuron disease which included ALS, PMA, and PBP, in part because it was almost impossible to distinguish the conditions at autopsy. Other researchers have suggested that PMA is just ALS in an earlier stage of progression, because although the upper motor neurons appear unaffected on clinical examination there are in fact detectable pathological signs of upper motor neuron damage on autopsy.[2]

Signs and symptoms

As a result of lower motor neuron degeneration, the symptoms of PMA include:[1]

- muscle weakness

- muscle atrophy

- fasciculations

- lack of tendon reflexes

Some patients have symptoms restricted only to the arms or legs (or in some cases just one of either). These cases are referred to as flail limb (either flail arm or flail leg) and are associated with a better prognosis.[5]

Diagnosis and Prognosis

PMA is a diagnosis of exclusion, there is no specific test which can conclusively establish whether a patient has the condition. Instead, a number of other possibilities have to be ruled out, such as multifocal motor neuropathy or spinal muscular atrophy. Tests used in the diagnostic process include MRI, clinical examination, and EMG. EMG tests in patients who do have PMA usually show denervation (neuron death) in most affected body parts, and in some unaffected parts too.[6]

Neurofilaments have also been studied as a way to diagnose PMA and other motor neurons diseases. Neurofilaments are a type of filament that helps neurons convey proteins.[7] They help diagnose PMA and differentiate it from other motor neuron diseases by measuring the amount of neurofilaments and what type it is. This method is typically used with other tests and signs, as diagnosing PMA can sometimes be difficult. Electromyograms (EMG) and blood tests are the main method of testing for PMA because EMGs can aid in nerve activity and blood tests can rule out other diseases.[8]

Sometimes PMA can seem to progress to ALS, meaning it was misdiagnosed.[9] When PMA develops symptoms that are related to the upper neurons diseases, the patient will go through more testing and be diagnosed to ALS.[10]

Differential diagnosis

In contrast to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or primary lateral sclerosis, PMA is distinguished by the absence of:[3][11]

- brisk reflexes

- spasticity

- Babinski's sign

- Increase in jaw jerking

- Lower cognitive activity

The importance of correctly recognizing progressive muscular atrophy as opposed to ALS is important for several reasons.

- The prognosis is a little better. A recent study found the 5-year survival rate in PMA to be 33% (vs 20% in ALS) and the 10-year survival rate to be 12% (vs 6% in ALS).[5]

- Patients with PMA do not have the cognitive change identified in certain groups of patients with MND.[12]

- Because PMA patients do not have UMN signs, they usually do not meet the World Federation of Neurology El Escorial Research Criteria for "Definite" or "Probable" ALS and so are ineligible to participate in the majority of clinical trials conducted in ALS.[5]

- Because of its rarity (even compared to ALS) and confusion about the condition, some insurance policies or local healthcare policies may not recognize PMA as being the life-changing illness that it is. In cases where being classified as being PMA rather than ALS is likely to restrict access to services, it may be preferable to be diagnosed as "slowly progressive ALS" or "lower motor neuron predominant" ALS.

An initial diagnosis of PMA could turn out to be slowly progressive ALS many years later, sometimes even decades after the initial diagnosis. The occurrence of upper motor neuron symptoms such as brisk reflexes, spasticity, or a Babinski sign would indicate a progression to ALS; the correct diagnosis is also occasionally made on autopsy.[13][14]

Prognosis

Individuals who are diagnosed with PMA typically have a longer survival rate than ALS.[3]About 56% of patients who were diagnosed with PMA lived for another 5 years or more, while with ALS only 14% of patients live for another 5 years.[10] The reason why PMA typically has a longer prognosis than ALS is because PMA only affects the lower motor neuron while ALS affects both the upper and lower motor neurons.

Treatment

The treatment for any motor neuron disease can be complex due to how the disease works. Motor neuron diseases involve the damage or degeneration of neurons, which don't heal or regenerate as quickly as other cells.[15] Currently, there is no cure for motor neuron diseases, which includes progressive muscular atrophy, but there are some treatments that can slow the progression of the disease.

The main treatment for PMA is physical therapy, which helps by maintaining the strength and flexibility of the lower body muscles affected by the disease. By using the muscles that are affected, the disease progression can possibly slow down and encourage independence.[16]

Stem Cells

Stem cells are special kind of cell that are able to self replicate and differentiate, which means that they are able to make other stem cells and branch into other kinds of cells.[17] The discovery of stem cells has helped developed new theories, opening the concept of using stem cells to treat difficult diseases. Current research has shown that stem cells can possibly be used in motor neuron diseases by protecting neurons from degeneration, but it can't regenerate neurons that have already been damaged.[18] Although stem cells sound like a new solution, they are still being research and no neural stem cell treatment has been approved by the FDA.

Notable cases

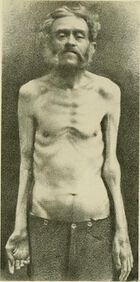

- Isaac W. Sprague - Entertainer and sideshow performer, billed as "the living human skeleton".

- Mike Gregory - Former Great Britain rugby league captain and head coach at Wigan RLFC

- Rob Rensenbrink - Former Netherlands and Anderlecht football player

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Wen, Xiangjin; Lan, Tianxiang; Su, Weiming; Cao, Bei; Wang, Yi; Chen, Yongping (2025-05-06). "Latest progress and challenges in drug development for degenerative motor neuron diseases" (in en). Neural Regeneration Research. doi:10.4103/NRR.NRR-D-24-01266. ISSN 1673-5374. PMID 40364643.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 "The history of progressive muscular atrophy: Syndrome or disease?". Neurology 70 (9): 723–727. Feb 2008. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000302187.20239.93. PMID 18299524.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Bos, Jeroen W.; Groen, Ewout J.N.; Wadman, Renske I.; Curial, Chantall A.D.; Molleman, Naomi N.; Zegers, Marinka; van Vught, Paul W.J.; Snetselaar, Reinier et al. (August 2021). "SMN1 Duplications Are Associated With Progressive Muscular Atrophy, but Not With Multifocal Motor Neuropathy and Primary Lateral Sclerosis". Neurology Genetics 7 (4): e598. doi:10.1212/NXG.0000000000000598. PMID 34169148.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Elsevier, Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary, Elsevier, http://dorlands.com/.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Natural history and clinical features of the flail arm and flail leg ALS variants.". Neurology 72 (12): 1087–1094. Mar 2009. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000345041.83406.a2. PMID 19307543.

- ↑ "Interpretation of electrodiagnostic findings in sporadic progressive muscular atrophy.". J. Neurol. 255 (6): 903–909. May 2008. doi:10.1007/s00415-008-0813-y. PMID 18484238.

- ↑ McCluskey, Gavin; Morrison, Karen; Donaghy, Colette; McConville, John; McCarron, Mark; McVerry, Ferghal; Duddy, William; Duguez, Stephanie (31 May 2023). "Serum Neurofilaments in Motor Neuron Disease and Their Utility in Differentiating ALS, PMA and PLS". https://scispace.com/pdf/serum-neurofilaments-in-motor-neuron-disease-and-their-3rds0yf7.pdf.

- ↑ "Muscle Atrophy: Causes, Symptoms & Treatment" (in en). https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22310-muscle-atrophy.

- ↑ Pereira, Ângela; Tkachenko, Nataliya; Fortuna, Ana Maria; Alonso, Isabel; Cardoso, Márcio; Da Silva, Jorge Diogo (2023-09-01). "An SPG7 mutation as a novel cause of monogenic progressive muscular atrophy" (in en). Neurological Sciences 44 (9): 3303–3305. doi:10.1007/s10072-023-06867-w. ISSN 1590-3478. PMID 37213040. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-023-06867-w.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Sontheimer, Harald (2021-01-01), Sontheimer, Harald, ed., "Chapter 6 - Diseases of Motor Neurons and Neuromuscular Junctions", Diseases of the Nervous System (Second Edition) (Academic Press): pp. 135–160, ISBN 978-0-12-821228-8, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128212288000068, retrieved 2025-09-25

- ↑ van Es, Michael A; Hardiman, Orla; Chio, Adriano; Al-Chalabi, Ammar; Pasterkamp, R Jeroen; Veldink, Jan H; van den Berg, Leonard H (2017-11-04). "Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". The Lancet 390 (10107): 2084–2098. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31287-4. ISSN 0140-6736. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673617312874.

- ↑ "Absence of cognitive, behavioral, or emotional dysfunction in progressive muscular atrophy". Neurology 67 (9): 1718–1719. Nov 2006. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000242726.36625.f3. PMID 17101922.

- ↑ "Sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis of long duration mimicking spinal progressive muscular atrophy exists: additional autopsy case with a clinical course of 19 years.". Neuropathology 24 (3): 228–235. Sep 2004. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1789.2004.00546.x. PMID 15484701.

- ↑ "Corticospinal tract degeneration in the progressive muscular atrophy variant of ALS.". Neurology 60 (8): 1252–1258. Apr 2003. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000058901.75728.4e. PMID 12707426.

- ↑ "Motor Neuron Diseases | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke" (in en). https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/motor-neuron-diseases.

- ↑ "progressive muscular atrophy". https://www.medicoverhospitals.in/diseases/progressive-muscular-atrophy/.

- ↑ "Answers to your questions about stem cell research" (in en). https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/bone-marrow-transplant/in-depth/stem-cells/art-20048117.

- ↑ Gowing, Genevieve; Svendsen, Clive N. (October 2011). "Stem cell transplantation for motor neuron disease: current approaches and future perspectives". Neurotherapeutics: The Journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics 8 (4): 591–606. doi:10.1007/s13311-011-0068-7. ISSN 1878-7479. PMID 21904789. PMC 3210365. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3210365/.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

|

KSF

KSF