Numerical differentiation

From HandWiki - Reading time: 11 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 11 min

In numerical analysis, numerical differentiation algorithms estimate the derivative of a mathematical function or subroutine using values of the function and perhaps other knowledge about the function.

Finite differences

The simplest method is to use finite difference approximations.

A simple two-point estimation is to compute the slope of a nearby secant line through the points (x, f(x)) and (x + h, f(x + h)).[1] Choosing a small number h, h represents a small change in x, and it can be either positive or negative. The slope of this line is This expression is Newton's difference quotient (also known as a first-order divided difference).

To obtain an error estimate for this approximation, one can use Taylor expansion of about the base point to give for some between and . Rearranging gives The slope of this secant line differs from the slope of the tangent line by an amount that is approximately proportional to h. As h approaches zero, the slope of the secant line approaches the slope of the tangent line and the error term vanishes. Therefore, the true derivative of f at x is the limit of the value of the difference quotient as the secant lines get closer and closer to being a tangent line:

Since immediately substituting 0 for h results in indeterminate form, calculating the derivative directly can be unintuitive.

Equivalently, the slope could be estimated by employing positions x − h and x.

Another two-point formula is to compute the slope of a nearby secant line through the points (x − h, f(x − h)) and (x + h, f(x + h)). The slope of this line is

This formula is known as the symmetric difference quotient. In this case the first-order errors cancel, so the slope of these secant lines differ from the slope of the tangent line by an amount that is approximately proportional to . Hence for small values of h this is a more accurate approximation to the tangent line than the one-sided estimation. However, although the slope is being computed at x, the value of the function at x is not involved.

The estimation error is given by where is some point between and . This error does not include the rounding error due to numbers being represented and calculations being performed in limited precision.

The symmetric difference quotient is employed as the method of approximating the derivative in a number of calculators, including TI-82, TI-83, TI-84, TI-85, all of which use this method with h = 0.001.[2][3]

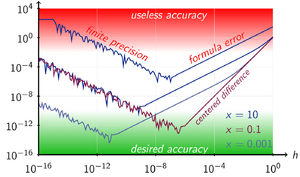

Step size

An important consideration in practice when the function is calculated using floating-point arithmetic of finite precision is the choice of step size, h. To illustrate, consider the two-point approximation formula with error term:

where is some point between and . Let denote the roundoff error encountered when evaluating the function and denote the computed value of . Therefore, The total error in the approximation is Assuming that the roundoff errors are bounded by some number and the third derivative of is bounded by some number , we get

To reduce the truncation error , we must reduce h. But as h is reduced, the roundoff error increases. Due to the need to divide by the small value h, all the finite-difference formulae for numerical differentiation are similarly ill-conditioned[4].

To demonstrate this difficulty, consider approximating the derivative of the function at the point . In this case, we can calculate which gives Using 64-bit floating point numbers, the following approximations are generated with the two-point approximation formula and increasingly smaller step sizes. The smallest absolute error is produced for a step size of , after which the absolute error steadily increases as the roundoff errors dominate calcuations.

| Step Size (h) | Approximation | Absolute Error |

|---|---|---|

For basic central differences, the optimal step is the cube-root of machine epsilon.[5] For the numerical derivative formula evaluated at x and x + h, a choice for h that is small without producing a large rounding error is (though not when x = 0), where the machine epsilon ε is typically of the order of 2.2×10−16 for double precision.[6] A formula for h that balances the rounding error against the secant error for optimum accuracy is[7] (though not when ), and to employ it will require knowledge of the function.

For computer calculations the problems are exacerbated because, although x necessarily holds a representable floating-point number in some precision (32 or 64-bit, etc.), x + h almost certainly will not be exactly representable in that precision. This means that x + h will be changed (by rounding or truncation) to a nearby machine-representable number, with the consequence that (x + h) − x will not equal h; the two function evaluations will not be exactly h apart. In this regard, since most decimal fractions are recurring sequences in binary (just as 1/3 is in decimal) a seemingly round step such as h = 0.1 will not be a round number in binary; it is 0.000110011001100...2 A possible approach is as follows:

h := sqrt(eps) * x; xph := x + h; dx := xph - x; slope := (F(xph) - F(x)) / dx;

However, with computers, compiler optimization facilities may fail to attend to the details of actual computer arithmetic and instead apply the axioms of mathematics to deduce that dx and h are the same. With C and similar languages, a directive that xph is a volatile variable will prevent this.

Three Point methods

To obtain more general derivative approximation formulas for some function , let be a positive number close to zero. The Taylor expansion of about the base point is

-

()

-

Replacing by gives

-

()

-

Multiplying identity (1) by 4 gives

-

()

-

Subtracting identity (1') from (2) eliminates the term:

which can be written as

Rearranging terms gives

which is called the three-point forward difference formula for the derivative. Using a similar approach, one can show

which is called the three-point central difference formula, and which is called the three-point backward difference formula.

By a similar approach, the five point midpoint approximation formula can be derived as:[8]

Numerical Example

Consider approximating the derivative of at the point . Since , the exact value is

| Formula | Step Size (h) | Approximation | Absolute Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Three-point forward difference formula | |||

| Three-point backward difference formula | |||

| Three-point central difference formula | |||

Code

The following is an example of a Python implementation for finding derivatives numerically for using the various three-point difference formulas at . The function func has derivative func_prime.

| Example implementation in Python |

import math

def func(x):

return (2*x) / (1 + math.sqrt(x))

def func_prime(x):

return (2 + math.sqrt(x)) / ((1 + math.sqrt(x))**2)

def three_point_forward(value, h):

return ((-3/2) * func(value) + 2*func(value + h) - (1/2)*func(value + 2*h)) / h

def three_point_central(value, h):

return ((-1/2)*func(value - h) + (1/2)*func(value + h)) / h

def three_point_backward(value, h):

return ((1/2)*func(value - 2*h) - 2*func(value - h) + (3/2)*func(value)) / h

value = 4

actual = func_prime(value)

print("Actual value " + str(actual))

print("============================================")

for step_size in [0.1, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001]:

print("Step size " + str(step_size))

forward = three_point_forward(value, step_size)

backward = three_point_backward(value, step_size)

central = three_point_central(value, step_size)

print("Forward {:>12}, Error = {:>12}".format(str(forward), str(abs(forward - actual))))

print("Backward {:>12}, Error = {:>12}".format(str(forward), str(abs(backward - actual))))

print("Central {:>12}, Error = {:>12}".format(str(forward), str(abs(central - actual))))

print("============================================")

|

| Output |

Actual value 0.4444444444444444

============================================

Step size 0.1

Forward 0.4443963018050967, Error = 4.814263934771468e-05

Backward 0.4443963018050967, Error = 2.5082646145202503e-05

Central 0.4443963018050967, Error = 5.231976394060034e-05

============================================

Step size 0.01

Forward 0.4444439449793336, Error = 4.994651108258807e-07

Backward 0.4444439449793336, Error = 2.507721614808389e-07

Central 0.4444439449793336, Error = 5.036366184096863e-07

============================================

Step size 0.001

Forward 0.4444444394311464, Error = 5.013297998957e-09

Backward 0.4444444394311464, Error = 2.507574814458735e-09

Central 0.4444444394311464, Error = 5.017960935660426e-09

============================================

Step size 0.0001

Forward 0.4444444443896245, Error = 5.4819926376126205e-11

Backward 0.4444444443896245, Error = 2.5116131396885066e-11

Central 0.4444444443896245, Error = 5.037903427762558e-11

============================================

|

Higher derivatives

Using Taylor Series, it is possible to derive formulas to approximate the second (and higher order) derivatives of a general function. For a function and some number , expanding it about and gives

and where . Adding these two equations gives

If is continuous on , then is between and . The Intermediate Value Theorem guarantees a number, say , between and . We can therefore write

where .

Numerical Example

Consider approximating the second derivative of the function at the point .

Since , the exact value is .

| Step Size (h) | Approximation | Absolute Error |

|---|---|---|

Arbitrary Derivatives

Using Newton's difference quotient, the following can be shown[9] (for n > 0):

Complex-variable methods

The classical finite-difference approximations for numerical differentiation are ill-conditioned. However, if is a holomorphic function, real-valued on the real line, which can be evaluated at points in the complex plane near , then there are stable methods. For example,[10] the first derivative can be calculated by the complex-step derivative formula:[11][12][13]

The recommended step size to obtain accurate derivatives for a range of conditions is .[14] This formula can be obtained by Taylor series expansion:

The complex-step derivative formula is only valid for calculating first-order derivatives. A generalization of the above for calculating derivatives of any order employs multicomplex numbers, resulting in multicomplex derivatives.[15][16][17] where the denote the multicomplex imaginary units; . The operator extracts the th component of a multicomplex number of level , e.g., extracts the real component and extracts the last, “most imaginary” component. The method can be applied to mixed derivatives, e.g. for a second-order derivative

A C++ implementation of multicomplex arithmetics is available.[18]

In general, derivatives of any order can be calculated using Cauchy's integral formula:[19] where the integration is done numerically.

Using complex variables for numerical differentiation was started by Lyness and Moler in 1967.[20] Their algorithm is applicable to higher-order derivatives.

A method based on numerical inversion of a complex Laplace transform was developed by Abate and Dubner.[21] An algorithm that can be used without requiring knowledge about the method or the character of the function was developed by Fornberg.[4]

Differential quadrature

Differential quadrature is the approximation of derivatives by using weighted sums of function values.[22][23] Differential quadrature is of practical interest because its allows one to compute derivatives from noisy data. The name is in analogy with quadrature, meaning numerical integration, where weighted sums are used in methods such as Simpson's rule or the trapezoidal rule. There are various methods for determining the weight coefficients, for example, the Savitzky–Golay filter. Differential quadrature is used to solve partial differential equations. There are further methods for computing derivatives from noisy data.[24]

See also

- Automatic differentiation – Techniques to evaluate the derivative of a function specified by a computer program

- Five-point stencil

- List of numerical-analysis software

- Numerical integration – Methods of calculating definite integrals

- Numerical methods for ordinary differential equations – Methods used to find numerical solutions of ordinary differential equations

- Savitzky–Golay filter – Algorithm to smooth data points

References

- ↑ Richard L. Burden, J. Douglas Faires (2000), Numerical Analysis, (7th Ed), Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0-534-38216-9.

- ↑ Katherine Klippert Merseth (2003). Windows on Teaching Math: Cases of Middle and Secondary Classrooms. Teachers College Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-8077-4279-2. https://archive.org/details/windowsonteachin00mers.

- ↑ Tamara Lefcourt Ruby; James Sellers; Lisa Korf; Jeremy Van Horn; Mike Munn (2014). Kaplan AP Calculus AB & BC 2015. Kaplan Publishing. p. 299. ISBN 978-1-61865-686-5.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Numerical Differentiation of Analytic Functions, B Fornberg – ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software (TOMS), 1981.

- ↑ Sauer, Timothy (2012). Numerical Analysis. Pearson. p.248.

- ↑ Following Numerical Recipes in C, Chapter 5.7.

- ↑ p. 263.

- ↑ Abramowitz & Stegun, Table 25.2.

- ↑ Shilov, George. Elementary Real and Complex Analysis.

- ↑ Using Complex Variables to Estimate Derivatives of Real Functions, W. Squire, G. Trapp – SIAM REVIEW, 1998.

- ↑ Martins, J. R. R. A.; Sturdza, P.; Alonso, J. J. (2003). "The Complex-Step Derivative Approximation". ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software 29 (3): 245–262. doi:10.1145/838250.838251.

- ↑ Differentiation With(out) a Difference by Nicholas Higham

- ↑ article from MathWorks blog, posted by Cleve Moler

- ↑ Martins, Joaquim R. R. A.; Ning, Andrew (2021-10-01) (in en). Engineering Design Optimization. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1108833417. http://flowlab.groups.et.byu.net/mdobook.pdf.

- ↑ "Archived copy". http://russell.ae.utexas.edu/FinalPublications/ConferencePapers/2010Feb_SanDiego_AAS-10-218_mulicomplex.pdf.

- ↑ Lantoine, G.; Russell, R. P.; Dargent, Th. (2012). "Using multicomplex variables for automatic computation of high-order derivatives". ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 38 (3): 1–21. doi:10.1145/2168773.2168774.

- ↑ Verheyleweghen, A. (2014). "Computation of higher-order derivatives using the multi-complex step method". http://folk.ntnu.no/preisig/HAP_Specials/AdvancedSimulation_files/2014/AdvSim-2014__Verheule_Adrian_Complex_differenetiation.pdf.

- ↑ Bell, I. H. (2019). "mcx (multicomplex algebra library)". https://github.com/ianhbell/mcx.

- ↑ Ablowitz, M. J., Fokas, A. S.,(2003). Complex variables: introduction and applications. Cambridge University Press. Check theorem 2.6.2

- ↑ Lyness, J. N.; Moler, C. B. (1967). "Numerical differentiation of analytic functions". SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 4 (2): 202–210. doi:10.1137/0704019. Bibcode: 1967SJNA....4..202L.

- ↑ Abate, J; Dubner, H (March 1968). "A New Method for Generating Power Series Expansions of Functions". SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 5 (1): 102–112. doi:10.1137/0705008. Bibcode: 1968SJNA....5..102A.

- ↑ Differential Quadrature and Its Application in Engineering: Engineering Applications, Chang Shu, Springer, 2000, ISBN 978-1-85233-209-9.

- ↑ Advanced Differential Quadrature Methods, Yingyan Zhang, CRC Press, 2009, ISBN 978-1-4200-8248-7.

- ↑ Ahnert, Karsten; Abel, Markus (2007). "Numerical differentiation of experimental data: local versus global methods". Computer Physics Communications 177 (10): 764–774. doi:10.1016/j.cpc.2007.03.009. ISSN 0010-4655. Bibcode: 2007CoPhC.177..764A.

External links

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Numerical Methods |

- Numerical Differentiation from wolfram.com

- NAG Library numerical differentiation routines

- Boost. Math numerical differentiation, including finite differencing and the complex step derivative

- Differentiation With(out) a Difference by Nicholas Higham, SIAM News.

|

KSF

KSF