Australian Skeptics

Topic: Organization

From HandWiki - Reading time: 38 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 38 min

| |

| Formation | 1980 |

|---|---|

| Purpose | "Investigating pseudo-science and the paranormal from a responsible scientific viewpoint" |

Region served | Australia |

| Website | skeptics |

Australian Skeptics is a loose confederation of like-minded organisations across Australia that began in 1980. Australian Skeptics investigate paranormal and pseudoscientific claims using scientific methodologies.[1] This page covers all Australian skeptical groups which are of this mindset. The name "Australian Skeptics" can be confused with one of the more prominent groups, "Australian Skeptics Inc", which is based in Sydney and is one of the central organising groups within Australian Skeptics.

Origins

In 1979, Mark Plummer (later president of Australian Skeptics) sent a letter to the American skeptical magazine The Zetetic in which he expressed interest in beginning a skeptical organisation in Australia. Sydney electronics entrepreneur Dick Smith responded to the letter, and offered to sponsor a visit to Australia by James Randi, the principal investigator for the American-based Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal (CSICOP), now known as the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSI), part of the non-profit organisation Center for Inquiry (CFI), which are joint publishers of the Skeptical Inquirer.[2][3][4][5][6][7] During this visit, James Randi, Dick Smith, Phillip Adams,[8] Richard Carleton and an unidentified businessman offered a $50,000 prize to anyone who could prove psychic phenomena in front of Randi. A number of contenders, largely water diviners came forward, but all failed to prove their claims in front of independent observers.[9]

The Australian Skeptics formed in 1980 out of this event, with the original purpose of continuing to test claims of the paranormal, with committee members Mark Plummer (president), James Gerrand (secretary), Joe Rubinstein (treasurer), and Allan Christophers,[5][4][10][11][12] as well as Bill Cook, John Crellin, Logan Elliot, Peter Kemeny, Loris Purcell, and Mike Wilton.[13] It was at this time that the group adopted the name "Australian Skeptics".[6] The amount of the prize was raised to AU$100,000 and it has been offered since then[14] (see The $100,000 Prize below). Very soon after the original formation of the Australian Skeptics in Victoria, Barry Williams from Sydney, New South Wales (NSW), responded to a call from Dick Smith seeking interest for new members.[15] He became involved, and the New South Wales committee formed.[5] The NSW committee included Barry Williams (president), Tim Mendham (secretary/treasurer), Mel Dickson, Dick Champion, Jean Whittle and others.[15] The Australian Skeptics are the second oldest English language skeptical group in the world after CSICOP in the US.[5] Tim Mendham joined the NSW committee from the very first meeting and went on to become secretary, treasurer, and editor of the magazine.[5]

In 1986, the year after the first national convention in Sydney (see below), Mark Plummer stepped down as national president when he began a new job as an executive officer at CSICOP in the US.[5] At this time the NSW Skeptics group took over the role as the national secretariat and the national committee, but the magazine production remained in Victoria with various editors including James Durand.[5][16][17][15] The national committee did not consist of representative from all the state organisations, but rather was just of the state groups which acted as the national organising committee.[5] "Australian Skeptics incorporated in NSW" (Australian Skeptics Inc. - ASI) became an incorporated association in 1986 in NSW with Barry Williams as president.[15]

ASI still operates today and is responsible for several national activities, such as the publication of The Skeptic magazine and coordination of awards (listed below) and the annual conventions.[1] Today ASI is one of many formal and informal skeptical groups throughout Australia that fall under the general umbrella title of "Australian Skeptics". Over time, other branches around Australia became incorporated including Australian Skeptics (Victorian Branch) Inc, Skeptics (S.A.) Incorporated, Hunter Skeptics Incorporated, Canberra Skeptics and Borderline Skeptics Inc (which caters for skeptics living around the NSW and Victorian border). ASI is the local group in NSW.[18]

In 1995 the Australian Skeptics received a sizeable bequest from the estate of Stanley David Whalley.[17][15] With these funds the organisation established the "Australian Skeptics Science and Education Foundation", tasked to expose "irrational activities and pseudoscience and to encourage critical thinking and the scientific view".[19] This foundation now funds the "Thornett award for promotion of reason", known affectionately as "the Fred", named after the late Fred Thornett, an influential figure in the skeptical movement in Tasmania and nationally.[20] "The Fred" is a $1000 prize given by ASI for significant contribution to educating or informing the public regarding issues of science and reason.[20] The bequest also allowed for the introduction of a paid position, that of executive officer. This position is answerable to the ASI committee, and traditionally manages accounts, queries from the public and media, editing The Skeptic, and various sundry tasks. Barry Williams was executive officer from 1995 to 2009, followed by Karen Stollznow (2009) and Tim Mendham from 2009 to the present.

In 1989 at a national committee meeting the aims of Australian Skeptics were updated and drafted as follows:

- To investigate claims of pseudoscientific, paranormal and similarly anomalous phenomena from a responsible, scientific point of view.

- To publicise the results of these investigations and, where appropriate, to draw attention to the possibility of natural and ordinary explanations of such phenomena.

- To accept explanations and hypotheses about paranormal occurrences only after good evidence has been adduced, which directly or indirectly supports such hypotheses.

- To encourage Australians and the Australian news media to adopt a critical attitude towards paranormal claims and to understand that to introduce or to entertain a hypothesis does not constitute confirmation or proof of that hypothesis.

- To stimulate inquiry and the quest for truth, wherever it leads.[1]

As of 2015, every state and territory within Australia has its own regional branch, and some have their own newsletters, with new local skeptics' groups springing up in Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide, Launceston and Darwin.[18][21]

Awards and prizes

Thornett Award for the Promotion of Reason

The Thornett Award for the Promotion of Reason, affectionately known as "The Fred" (much like the Academy Award is known as the "Oscar"), is named after Fred Thornett, a noted member of Australian Skeptics from Tasmania who died in April 2009.[22] The Fred award includes a $2000 cash prize (increased from $1000 in 2018)[23] that is given to the recipient or to a charity or cause of their choice. It is awarded annually to a member of the public or a public figure who has made a significant contribution to educating or informing the public regarding issues of science and reason.[20][24]

| Year | Winner | Reason |

| 2025 | Robyn Williams | “'Robyn is a justifiably famous national living icon, and his dedication to science, reason and truth over the years makes him a highly worthy winner.'”[25] |

| 2024 | Dr Nikki Milne[26] | |

| 2023 | Nathan Eggins[26] | |

| 2021 | Prof Kristine Macartney, NCIRS[26] | |

| 2020 | Dr Vyom Sharma | GP and magician, who has maintained his cool while imparting information that is both accurate and understandable when bringing his medical and scientific expertise to bear on COVID-19, despite what has been a hazardous road full of pseudoscientific pitfalls. |

| 2019 | Guy Nolch | Former publisher of the magazine Australasian Science which ceased publication in 2019.[27] |

| 2018 | Ian Musgrave | For being a long-standing and effective science communicator in the area of pharmacology and providing a voice of reason in challenging "chem-phobia".[28] |

| 2017 | John Cunningham | In recognition of his continued and authoritative exposure of chiropractic misconduct and anti-vaccination misrepresentation.[29] |

| 2016 | Jill Hennessy MP | For courageously facing down those who misrepresent and mislead the public in their promotion of dodgy medical claims and practices.[30] |

| 2015 | Catherine & Greg Hughes "Light for Riley" | Continuing the fight against vaccine preventable diseases after the death of their son Riley from pertussis.[31] |

| 2014 | Northern Rivers Vaccination Supporters | A grassroots pro-vaccination group in a northern NSW region which has among the lowest vaccination rates in the country.[24][32] |

| 2013 | Sonya Pemberton | For her documentary Jabbed, a dramatic presentation on the impact of delaying or refusing immunisation.[33] |

| 2012 | Adam vanLangenberg | For his work in founding McKinnon Secondary College in Melbourne’s skeptical club.[34][35][36] |

| 2011 | Ken Harvey | For taking great personal risks in exposing pseudomedicine claims, including his much publicised stoush with the SensaSlim company.[37][38][39][40] |

| 2010 | Wendy Wilkinson and Ken McLeod | For their relentless campaign to ensure that the Australian (anti)Vaccination Network's activities are brought into the light of official scrutiny, and their subsequent success in this campaign. The prize in 2010 was doubled (not shared).[41][42] |

| 2009 | Toni and David McCaffery | For their unstinting and extremely brave efforts on behalf of children in the face of the anti-vaccination movement.[43][44][45] |

Skeptic of the Year

The Skeptic of the Year award is given annually to someone associated with the skeptical community who has been particularly active over the previous year. ASI coordinates the prize, and the final decision is voted on by representatives from the various Australian Skeptics groups.

| Year | Winner |

| 2023 | Paul Gallagher[26] |

| 2020 | Mandy-Lee Noble[46] |

| 2017 | Christine Bayne[29] |

| 2016 | Mal Vickers and Ken Harvey[30] |

| 2014 | Peter Tierney[32][47] |

| 2013 | Simon Chapman[33][48][49][50][51] |

| 2012 | Friends of Science in Medicine[52][53][54][55][56][57] |

| 2011 | Loretta Marron[37][38][53][54][58] |

| 2010 | Stop the AVN[42][59] |

| 2007 | Loretta Marron[53][54][58][60] |

| 2006 | Karl Kruszelnicki[61][62][63][64] |

| 2004 | Lynne Kelly[65] |

| 2002 | Paul Willis[66][67] |

| 2000 | John Dwyer[68] |

| 1999 | Cheryl Freeman[69] |

| 1998 | Mike Archer[70][71] |

| 1997 | Peter Doherty[48][72] |

| 1996 | Derek Freeman[73] |

Barry Williams Award for Skeptical Journalism

The Barry Williams Award for Skeptical Journalism which recognises "the best piece of journalism (in any medium) that takes a critical and skeptical approach to a topic" within the scope of the Australian Skeptics. The award is named in memory of Barry Williams who died in 2018 and carries a $AU2000 prize. Williams was a past president and executive officer of Australian Skeptics who regularly appeared in the Australian media. The award has been nicknamed "the Wallaby" after the nom-de-plume Sir Jim R Wallaby, used by Williams in some of his more whimsical writing.[23]

| Year | Winner | Reason |

| 2025 | Henrietta Cook and Liam Mannix | For "'their story on the use of the toxic substance belladonna for infant colic.'"[25] |

| 2024 | Henrietta Cook [26] | |

| 2023 | Media Watch[26] | |

| 2021 | Melissa Davey[26] | |

| 2020 | Dr Norman Swan, and Science Friction (Click-Sick episodes) | Dr Norman Swan of the ABC Health Report, and the ABC Radio National program Science Friction, have both presented serious, rational and uncompromising pieces on the COVID-19 pandemic and how to deal with its effects, across a range of media platforms. |

| 2019 | Liam Mannix | Reporter who writes with a critical approach for The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald.[27] |

| 2018 | Jane Hansen[74] | Reporter for News Corp, who has written extensively on the anti-vaccination and anti-fluoride movements, fad diets, and quack cures.[28] |

Bent Spoon Awards

The Bent Spoon Award is an annual award coordinated by ASI, although the final decision is voted on by representatives from the various groups comprising Australian Skeptics. It is "presented to the perpetrator of the most preposterous piece of paranormal or pseudoscientific piffle" in a tongue-in-cheek fashion.[56][75] The group describe the award trophy as follows:

A piece of timber, which we had no reason to doubt was an off cut of gopher wood from the Ark construction site, was polished to a high gloss and thereupon was affixed a spoon, which, rumour suggests, may have been used at the Last Supper. The spoon, having been tastefully bent into a graceful curve, by energies that are, we suspect, unknown to science, is plated with gold by means of a deposition process long thought lost with the submergence of Atlantis.[76]

Although awarded annually since 1982, only one copy of the trophy exists, as "anyone wishing to acquire the trophy must remove it from our keeping by paranormal means" and no winner has yet overcome this obstacle.[76]

The award is offered only to Australian individuals or groups, or those who have carried out their activities in Australia.[56][76][77][78] The New Zealand Skeptics have a similar Bent Spoon Award.[79]

| Year | Winner | Position | Reason |

| 2025 | Barbara O'Neill | naturopath | "'In 2019, the Health Care Complaints Commission in New South Wales ruled that she is prohibited from providing any health-related services in Australia. An investigation found that she provided dangerous advice to vulnerable patients'".[25] |

| 2024 | Cancer Council WA | For endorsing the practices of reiki and reflexology.[80] | |

| 2023 | Ross Coulthart | Award-winning journalist | For espousing UFO conspiracies, including unsubstantiated claims that world governments and The Vatican are hiding extraterrestrial alien bodies and spacecraft on Earth.[81] |

| 2022 | Maria Carmela Pau | Spiritual healer and self-described COVID denier[82] | For pretending to be a medical doctor to issue false COVID exemptions, reportedly making $120,000 from 1200 certificates.[83] |

| 2021 | Craig Kelly | United Australia Party MP | For misinformation about COVID and vaccinations for some time, offering dubious cures, conspiracy theories, and an interesting way with statistics[84] |

| 2020 | Pete Evans | Former celebrity chef | For the promotion of the pseudoscientific non-medical BioCharger and continuing his anti-vaccination position.[85] |

| 2019 | SBS-TV | TV program – Medicine or Myth? | For misinforming the public as to how products and therapies can or should be tested for safety and effectiveness.[27] |

| 2018 | Sarah Stevenson | Video blogger "Sarah's Day" | For spreading misinformation about health via her online following of over 1 million people.[28] |

| 2017 | National Institute of Complementary Medicine at the University of Western Sydney[29] | For continuing to promote unproven treatments and being involved in a project to establish a traditional Chinese medicine clinic on campus.[29] | |

| 2016 | Judy Wilyman, Brian Martin and the Faculty of Social Sciences at University of Wollongong | For awarding a doctorate on the basis of a PhD thesis riddled with errors, misstatements, poor and unsupported 'evidence' and conspiratorial thinking.[30] | |

| 2015 | Pete Evans | Chef, author and television personality | For his support of pseudomedicine, his stance against fluoridation, and his association with Stephen Mercola.[86] |

| 2014 | Larry Marshall | Chief Executive, CSIRO | For his support of water divining.[32][56][87][88][89] |

| 2013 | Chiropractors' Association of Australia and the Chiropractic Board of Australia | For failing to ensure their own members – including some committee members – adhere to their policy announcements.[56][90][91] | |

| 2012 | Fran Sheffield | Homeopathy Plus! | For advocating the use of magical sugar and water in place of tried and true vaccination for many deadly diseases, most notably whooping cough.[34][52][92][93][94] |

| 2011 | RMIT University (Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology) | For having a fundamentalist chiropractic education program – if the word education can be used in this way – and for endorsing the practice by targeting children and infants in their on-campus paediatric chiropractic clinics.[37][38][57] | |

| 2010 | The Australian Curriculum and Reporting Authority (ACARA) | For its draft science curriculum.[42] | |

| 2009 | Meryl Dorey and the deceptively named Australian Vaccination Network ∞ | For spreading fear and misinformation about vaccines.[45][56][95][96][97][98] | |

| 2008 | Kerryn Phelps | Former head of the AMA | For lending her name to a clinic offering various unproven ‘alternative’ remedies.[99] |

| 2007 | Marena Manzoufas | Head of programming at the ABC | For authorising the television show Psychic Investigators.[78] |

| 2006 | The pharmacists of Australia | For managing to forget their scientific training long enough to sell quackery and snake oil (such as homoeopathy and ear candles) in places where consumers should expect to get real medical supplies and advice.[Editorializing][64][100] | |

| 2005 | The ABC television program Second Opinion | For the uncritical presentation of many forms of quackery.[78][101] | |

| 2004 | The producers of the ABC television show The New Inventors | Principally for giving consideration to an obvious piece of pseudoscience, the AntiBio water conditioning system.[65][78] | |

| 2003 | The Complementary Healthcare Council[102] | ||

| 2002 | Gentle Heal Pty Ltd | For the selling of fake (homoeopathic) vaccine.[103] | |

| 2001 | The Lutec "Free Energy Generator"[104] | ||

| 2000 | Jasmuheen | For claiming one can live without food and water.[68] | |

| 1999 | Mike Willesee | For the documentary Signs From God.[69][105][106] | |

| 1998 | Southern Cross University | For offering a degree course in naturopathy, while also claiming to be conducting research into whether there was actually any validity to naturopathy.[71] | |

| 1997 | Viera Scheibner | Anti-immunisation advocate.[56][72] | |

| 1996 | Marlo Morgan | American new age author | For claiming in her book, Mutant Message Downunder, that Australian Aborigines could levitate.[73] |

| 1995 | Tim McCartney-Snape | for promotion of the beliefs of Jeremy Griffith self described prophet and founder of the World Transformation Movement, the Foundation for the Adulthood of Mankind.[107][108] | |

| 1994 | Commonwealth Attorney-General | For an enterprise agreement with its 2,400 employees that included a clause so any employee, who had taken sick leave, need not provide a medical certificate signed by a medical practitioner, but could provide one signed by a naturopath, herbalist, iridologist, chiropractor or one of assorted other "alternative" practitioners.[109] | |

| 1993 | Steve Vizard | Tonight Live television programme on Channel 7.[110][111] | |

| 1992 | Allen S Roberts | Archaeological research consultant and fundamentalist pastor | For a search for Noah’s Ark.[112] |

| 1991 | Woman's Day magazine | For its coverage and support of the paranormal, in particular astrology.[113] | |

| 1990 | Mafu | Multilifed entity | For being channelled by Penny Torres Rubin and who, despite millennia of experience, was remarkable for the banality of his/her pronouncements.[114][115] |

| 1989 | Diane McCann | For writing that Adelaide was built on one of the temples of Atlantis.[114][116] | |

| 1988 | None | ||

| 1987 | Anne Dankbaar | Adelaide psychic | For her discovery of the Colossus of Rhodes, which created something of a media stir until it was shown to be modern builder's rubble.[114][116] |

| 1986 | Peter Brock | Prominent racing driver | For his highly touted "energy polariser" which generated more heat in the motoring media than it did energy in his car.[114][116][117][118][119] |

| 1985 | The Findhorn Festival Group | For sponsoring the visit to Australia of American psychic dentist Willard Fuller. "Brother" Willard left town just ahead of some injunctions from real dentists.[114][117] | |

| 1984 | Melbourne Metropolitan Board of Works | For its payment of $1,823 to US psychic archaeologist Karen Hunt to use divining rods to detect an alleged "electromagnetic photo field".[114][116] | |

| 1983 | Dennis Hassel | Melbourne mystic | For the trick of making his hand disappear.[114][120] |

| 1982 | Tom Wards | Self-proclaimed psychic | For predictions in the popular press which were renowned for their inaccuracy.[56][114][120] |

∞ In 2012 the Australian Vaccination Network was ordered by the New South Wales Office of Fair Trading to change its name within two months.[121][122][123] The order was challenged, but the challenge was dismissed, and in 2014 the group changed its name to the Australian Vaccination-Skeptics Network.[124]

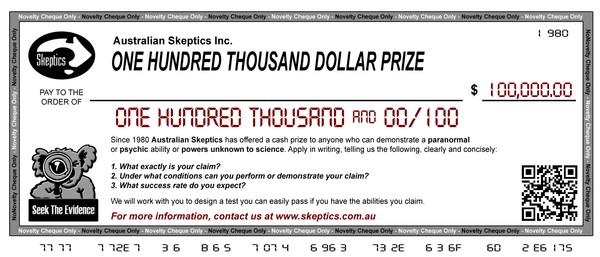

$100,000 Prize

Since its foundation in 1980, Australian Skeptics has been offering a cash prize to anyone who can prove they have psychic or paranormal powers and is able to demonstrate their ability under proper observing conditions. The offer has been made in an effort to seek out the truth of paranormal claims such as those of psychics, healers, witnesses to paranormal events and those selling devices which claim to defy scientific laws.[125][126] If someone nominates another person, and that person is successful, then 20% of the prize may be awarded to the nominator.[127]

The challenge originally offered $50,000 to any water diviner who was able to demonstrate their powers, and it was later raised, with contributions from various sources, to AU$100,000 offered to anyone who could demonstrate any form of paranormal or psychic ability unknown to science.[128][6] Up to the end of 2018, more than 200 claims have been seriously investigated but none of them has produced a positive result.[14]

This challenge is now coordinated by ASI and the prize money is backed by the Australian Skeptics Science and Education Foundation. It is open to any contender who can state exactly what their paranormal claim is, and the claim can give a definite yes or no result. They must define under what conditions the claim can be performed, and expect to beat million to one odds in order to claim success. The result of each test is then published in The Skeptic, the magazine of Australian Skeptics. ASI states that should any contender pass the challenge, and be awarded the prize, they want to tell the world and give the claimant proper recognition. If, however, a claim is proved to be unfounded or fraudulent, the association reserve the right to expose this result in an effort to prevent clients from spending time and money on a product or service that cannot deliver what is claimed for it.[125]

Eureka / Critical Thinking Prize

The Australian Museum Eureka Awards is a series of annual awards presented by the Australian Museum in partnership with their sponsors, for excellence in various fields. Until 2005 the Australian Skeptics were major sponsors of the award for critical thinking, which during this period was awarded to:[20]

| Year | Winner |

| 1996 | Trevor Case[73][129] |

| 1997 | Amanda Barnier[130][131][132] |

| 1999 | Melissa Finucane[133] ∞ |

| 2000 | Richard Kocsis[134] |

| 2001 | Tim van Gelder[135][136][137][138] |

| 2002 | Robert Morrison[139][140][141][142] |

| 2003 | Brendan McKay[143][144] |

| 2004 | Cheryl Capra[145] |

| 2005 | David Henry & Amanda Wilson[146][147][148][149] |

∞ The 2000 Spring edition of The Skeptic magazine erroneously listed Richard Kocsis as the 1999 winner[150]

After 2005 the Australian Skeptics decided to withdraw from the Eurekas, and award their own critical thinking Prize known as the Australian Skeptics Critical Thinking Prize. The winners are as follows:[20]

| Year | Winner |

| 2006 | Martin Bridgstock[64][151][152] |

| 2007 | Kylie Sturgess[60][153][154] |

| 2008 | Peter Ellerton[99][155][156][157] |

Both of these prizes have been discontinued.[20]

-

The map of Australia in the shape of a question mark was adopted as the official logo by the Australian Skeptics in 1996 and is a registered trademark image of the Australian Skeptics Inc. All Australian skeptical groups have been granted unconditional licence to use the image.

-

Australian Skeptics Inc. former president Eran Segev on the secrets of an effective skeptical organisation.

Regional and state groups

New South Wales

Victoria

- Australian Skeptics (Victorian Branch) Inc.[18]

- Ballarat Skeptics[21]

- Borderline Skeptics Inc.[18]

- Citizens for Science

- Great Ocean Road Skeptics[21]

- Melbourne Eastern Hills Skeptics in the Pub[21]

- Melbourne Skeptics[21]

- Mordi Skeptics[21]

- Young Australian Skeptics[158]

Queensland

- Brisbane Skeptic Society Inc.[21][159]

- Gold Coast Skeptics[18]

- Queensland Skeptics Association Inc.[18]

Australian Capital Territory

- Canberra Skeptics[18]

Western Australia

South Australia

- Skeptics SA

- Thinking and Drinking

Tasmania

- Hobart Skeptics[18]

- Launceston Skeptics

Northern Territory

- Darwin Skeptics[18]

Past events

National conventions

The Australian Skeptics National Convention is the longest running annual skeptical convention,[162] and has been held annually since 1985.

| Year | Dates | Location | ||

| 39 | 2025 | 3-5 October | Melbourne[25] | |

| 38 | 2024 | 23–25 November | Sydney | |

| 37 | 2023 | 2-3 December | Melbourne | |

| 36 | 2022 | 3-4 December | Canberra | |

| 35 | 2019 | 6-8 December | Melbourne (Carrillo Gantner Theatre, Carlton)[163] | |

| 34 | 2018 | 13-14 October | Sydney (The Concourse, Chatswood)[164] | |

| 33 | 2017 | 18–19 November | Sydney (City Recital Hall)[165] | |

| 32 | 2016 | 25–27 November | Melbourne (University of Melbourne)[166] | |

| 31 | 2015 | 16–18 October | Brisbane (QUT)[167][168] | |

| 30 | 2014 | 28–30 November | Sydney (The Concourse, Chatswood)[169] | |

| 29 | 2013 | 22–24 November | Canberra (CSIRO Discovery Centre)[170] | |

| 28 | 2012 | 30 November – 2 December | Melbourne (Melbourne University)[171] | |

| 27 | 2011 | 19 November (one-day event) | Sydney (Australian Museum)[38] | |

| 26 | 2010 | 28–30 November | Sydney TAM Australia (Sydney Masonic Centre)[172] | |

| 25 | 2009 | 27–29 November | Brisbane (University of Queensland)[173] | |

| 24 | 2008 | October | Adelaide (Norwood Town Hall)[174] | |

| 23 | 2007 | November | Hobart (University of Tasmania)[175] | |

| 22 | 2006 | November | Melbourne (Melbourne Museum)[176] | |

| 21 | 2005 | August | Gold Coast (Bond University)[177] | |

| 20 | 2004 | November | Sydney (University of Technology, Sydney)[178] | |

| 19 | 2003 | August | Canberra (CSIRO Discovery Centre)[179] | |

| 18 | 2002 | November | Melbourne (Melbourne University)[180] | |

| 17 | 2001 | November | Brisbane (West End Club)[181] | |

| 16 | 2000 | November | Sydney World Skeptics Convention III (Sydney University)[182] | |

| 15 | 1999 | November | Adelaide (Adelaide Convention Centre)[183] | |

| 14 | 1998 | October–November | Canberra (National Science & Technology Centre)[184] | |

| 13 | 1997 | August | Newcastle (Western Suburbs – Newcastle – Leagues Club)[185] | |

| 12 | 1996 | September | Melbourne (Monash University)[186] | |

| 11 | 1995 | June | Melbourne (Melbourne University)[187] | |

| 10 | 1994 | June | Sydney (Willoughby Town Hall)[188] | |

| 9 | 1993 | June | Melbourne (Melbourne University)[189] | |

| 8 | 1992 | June | Newcastle (Western Suburbs – Newcastle – Leagues Club)[190] | |

| 7 | 1991 | June | Sydney (Manly-Warringah Leagues Club)[191] | |

| 6 | 1990 | June | Melbourne (Holmesglen Conference Centre[192] | |

| 5 | 1989 | March | Canberra (National Science & Technology Centre)[193] | |

| 4 | 1988 | April | Sydney (Manly-Warringah Leagues Club)[194] | |

| 3 | 1987 | April | Canberra (Aust National University)[195][196] | |

| 2 | 1986 | March | Melbourne (Monash University)[15][4] | |

| 1 | 1985 | April | Sydney (Institution of Engineers)[197] |

No Answers in Genesis

No Answers in Genesis[198] is a website affiliated with the Australian Skeptics organisation that provides information to defend the theory of evolution, and, more specifically, counter young Earth creationist arguments put forward by Answers in Genesis. It was founded by Australian atheist and skeptic John Stear, a retired civil servant. The website contains links, essays and other postings that rebut creationist arguments against evolution. Stear states that the site is meant for educational purposes as well as to illustrate the problems with young Earth creationism. The site also contains simple introductions to evolutionary concepts. It mainly has posts on creationism, but now has some essays on "intelligent design".[199] It has two discussion boards.[200][201]

In June 2005, members of the creationist group Answers in Genesis – Australia debated a team from the Australian Skeptics online on Margo Kingston's web diary section of the Sydney Morning Herald website.[202]

Psychic hoaxes

In 1984 the Australian Skeptics brought magician Bob Steiner to Australia to pose as a psychic under the name "Steve Terbot". He went on The Bert Newton Show with Derryn Hinch who was in on the hoax, and accused him of being a charlatan. He also performed shows to live audiences in Melbourne and Sydney, pretending to be psychic. He later returned to the Bert Newton Show to reveal that he was a magician performing a hoax.[4]

Later in February 1988 Richard Carleton, a reporter on the TV show 60 Minutes, brought James Randi back to Australia to oversee an elaborate hoax involving a fictional character named Carlos who was reported to be a 2,000-year-old entity who had last appeared in the body of a 12-year-old boy in Venezuela in 1900 was now manifesting through a young American art student named José Alvarez.[5][203] In reality José had no special abilities,[6] and was actually Randi's partner and assistant.[203] The hoax involved the character Carlos appearing on various television shows in character[5] and culminated in channel nine hosting a large media event at the Sydney Opera House where members from the Australian Skeptics were interviewed in front of a large audience of believers.[5] The Australian Skeptics had not been made aware of the hoax until hours before it was revealed, a few days later, on 60 Minutes.[204][205][206] There was outrage amongst the Australian media, to which Randi responded by pointing out that none of the journalists had bothered with even the most elementary fact-checking measures.[203] There were some among the Australian Skeptics who took the view that this hoax had the potential of harming the good relationships that had been formed with certain media organisations, possibly discouraging them from reporting critically on similar stories in the future, and instead leaving such stories to other, less skeptical media organisations.[207]

Historical investigations and demonstrations

Over the years the Australian Skeptics have conducted many investigations and demonstrations. Some examples are as follows:

Divining

In the early 1980s Dick Smith brought James Randi to Australia to conduct a test to determine whether those who conduct water divining have any real abilities.[6][208][17] They laid out a grid of plastic irrigation pipes which were able to have water flowing or not flowing, and then challenged water diviners to determine which pipes contained the running water.[9] Prior to the testing, the diviners agreed that the experimental conditions were suitable, however, when they were unable to display any ability, they changed their positions and blamed various external influences for preventing their success.[6][208] This experiment was repeated several times beginning in 2001 using bottled water and bottled sand hidden within paper bags, with similar results.[17]

Water powered car

In 1983 Ian Bryce and Mark Plummer investigated a patent filed for a "water powered car", designed by Stephen Horvath.[209] The car was well publicised in the media of the day, and promoted by the then Premier of Queensland; Joh Bjelke-Petersen.[16] The investigation concluded that the claim that the car was powered by nuclear fusion was not supported by evidence.[209]

Psychic surgery

In 1981 when James Randi was visiting Australia he demonstrated how psychic surgery can be performed by sleight of hand with no actual surgery taking place.[210] This was then later demonstrated again by the Australian Skeptics at a convention held in Sydney.[16][15] The publicity from these demonstrations led to other forms of media, including the Australian Penthouse magazine publishing the story.[16][210]

Fire walking

The Victorian Skeptics have demonstrated several times how firewalking or lying on a bed of nails can be achieved without any harm to the person. As publicity stunts they had various celebrities such as Steve Moneghetti, as well as committee members including Barry Williams, demonstrate fire walking, and then invited members of the public to repeat the stunt.[4][211][15]

Telepathy

In 2010, a $100,000 prize challenger named Barrie Hill claimed to have the ability to transfer information by paranormal means, i.e. not through established communications or other physical means, from Australia to the USA. A test protocol was developed and agreed to by both parties. On test day, the Sydney "transmit" team assembled and was ready to execute the test, but in New York, the "receiver", known only as "Sue" and her lawyer "Jamie", did not show up to the agreed location. Hill claimed that they could not be reached by cell phone as they did not use them due to concerns over health. The test was eventually called off.[212] After the first attempt, Hill explained that the receiver team was stuck in an elevator on the test date, and asked for another test. The investigation team insisted on speaking to the receiver, and asked the name. Hill replied it was "An Indian Spirit Guide."[213]

Cold Fusion

On behalf of Australian entrepreneur Dick Smith, the Australian Skeptics performed an investigation of Andrea Rossi's Energy Catalyzer purported cold fusion generator. Several reviewers, including 2 nuclear physicists, had previously observed the device in operation and found it worth more study. Bryce's investigation postulated that extra energy was being added into the system through an unmetered earth ground wire.[213][214]

Wine Card

In 2014 the Australian Skeptics investigated a product marketed by a Brisbane company known as the 'Premium Wine Card'. The device was the size of a credit card with holes punched in it that one would press against a glass when wine was poured in. The claim is that 'embedded frequencies' in the card improve the taste of wine, and was sold for about sixty-five dollars. Investigators devised an informal test using a placebo wine card, and placed both cards into identical envelopes, after which they invited participants to select which glass of wine was superior. The test was performed with two types of wine of differing price and with tap water. Sixty-six trials were performed. The results showed no correlation between use of the wine card on samples and the preference of the participants.[215]

Publications

The Skeptic magazine

The journal of the Australian Skeptics is called The Skeptic. The first issue of The Skeptic came out of Melbourne in January 1981, edited by Mark Plummer and produced by James Gerrand.[216] The first issue was a black and white broadsheet tabloid.[5] For many years the logo was the same logo as the American publication the Skeptical Inquirer only photocopied with the end chopped off. After that first issue, the format was reduced to a standard A4 publication produced on a typewriter.[5][4] In the early days of the Australian Skeptics there was a strong focus on media and outreach, and the magazine ran a special column in each issue listing all media coverage for that period.[5] After the national secretariat moved up to NSW in 1986, the production of the magazine was moved to the Sydney branch in 1987 with Tim Mendham as the new editor, and at this time the magazine was produced on a computer (a Macintosh) for the first time.[5][15] About a year before the change, there was a competition held to choose a new logo for the Australian Skeptics, and this new logo was used in the magazines up until the 1990s.[5] In 1988 for the first time the magazine was produced with a cover, showing the title and various art work, and for a few years after that the publication was produced in a different colour for each issue.[5] In 1990 Tim Mendham stepped down as editor and Barry Williams took on the role, intending to only edit one issue in 1991, but then remaining in the role until 2008.[5] Both Karen Stollznow[217] and Steve Roberts[218] were editors briefly in 2009, until editing was handed back to Tim Mendham in June 2009, and with whom it remained until the printed magazine stopped being published in 2025 and the magazine became an online only publication.[216][5][15][219]

Books

The first big project that the Australian Skeptics undertook was in the 1980s when two scientists, Martin Bridgstock and Ken Smith, researched the various claims of creationism, and the Australian Skeptics, along with other authors, published a very successful book detailing their debunking of creationist claims.[5][15] The book, titled Creationism: An Australian Perspective was first published 1986.[220] At this time creationism was still being taught in science classes in some public schools in Queensland, but this research led to campaigns led by Martin Bridgstock, which resulted in creationism being removed from science classes.[5] Ken Smith and Martin Bridgestock were both awarded the first life memberships in the Australian Skeptics at the 1986 convention for this service.[15]

The Australian Skeptics also re-published the book Gellerism Revealed: The Psychology and Methodology Behind the Geller Effect by Ben Harris, originally published in 1985.[221][5]

The Canberra Skeptics also published a book titled Skeptical which gave one- to two-page overviews of various skeptical topics.[5]

Booklet

During the creationism in science classes debate, the Australian Skeptics attended a talk by a creationist geologist and collected various leaflets at that event. They responded to the leaflets by setting up a small sub-committee for the purpose of researching and responding to the various points raised in the creationist leaflets. The results of this research were published in a booklet in 1991 titled "Creationism-Scientists Respond".[4]

Skeptical Australian podcasts and radio programs

| Independent and affiliated podcasts of a skeptical nature produced in Australia | ||||

| Podcast | Host / creator | Dates | Details | Affiliation |

| Brains Matter | "The Ordinary Guy" | October 2006 to present | Brains Matter is a podcast discussion of science, trivia, history, curiosities and general knowledge.[222][223][224] | |

| Diffusion Science Radio | Ian Woolf | November 1999 to present |

Diffusion Science Radio is a weekly science and technology community radio show and podcast featuring a mix of new science, hard science, pop science, historical science and very silly science.[224][225] |

|

| Dr Karl's Great Moments in Science | Karl Kruszelnicki | Great Moments in Science is a short podcast featuring easy to understand explanations of interesting science topics and recent discoveries.[226][227] | ABC Science | |

| Einstein A Go-Go | Dr Shane | A discussion show about science.[228] | 3RRR | |

| Hunting Humbug 101 | Theo Clark | 27 May 2014 to present | Hunting Humbug 101 is a biweekly podcast that examines logical fallacies using examples from the media, discussing pseudoscience, science misconceptions, politics, and philosophy.[222][224] | Humbug! the eBook |

| The Imaginary Friends Show | Jake Farr-Wharton | 8 February 2011 to present |

The Imaginary Friends Show is a twice-weekly panel style podcast covering topics including science, skepticism, secularism, religion and politics, as well as irrational, illogical and dangerous posed beliefs.[222][229] |

Independent |

| Mysterious Universe | Aaron Wright and Benjamin Grundy | 2006 to present | Mysterious Universe is a weekly podcasts covering issues and events that are strange, extraordinary, weird, wonderful and everything in between.[222][230] | |

| Smart Enough To Know Better | Greg Wah and Dan Beeston | June 2010 to present |

Smart Enough to Know Better is a bi-weekly skeptical podcast including chat, sketches and interviews about science and skepticism.[222] |

|

| Reality Check | Tony Pitman | July 2009 to present |

Reality Check is a radio show and podcast produced at the studios of JOY 94.9 FM in Melbourne. Each episode includes a round-up of LGBT world news and a movie review, along with a skeptical analysis of an issue related to pseudoscience, the paranormal or religion.[231][232] |

|

| Skeptically Challenged | Ross Balch | 2 June 2013 to present | Skeptically Challenged a forum for exposing pseudoscience. It includes a regular podcast, combined with blogging and YouTube videos about issues in pseudoscience as well as the skeptic community at large and the promotion of scientific and critical thinking within the community.[222][233] | Independent |

| Ockham's Razor | Robyn Williams | Ockham's Razor is a weekly radio program on ABC Radio National with short talks by researchers and people from industry with something thoughtful to say about science.[234] | ABC Radio National | |

| The Pseudoscientists | Jack Scanlan, Rachael Skerritt, Tom Lang, Sarah McBride and Elizabeth Riaikkenen | 23 December 2008 to present | The Pseudoscientists is a panel discussion podcast covering topics including science, skepticism, news and pop-culture.[222][235] It is created by the Young Australian Skeptics, who are a group of young Australian science communicators, professionals and students, with an interest in science, critical thinking, religion, education, politics, medicine, law, wider society, scientific skepticism and its cultural impact.[224][236][237] | Young Australian Skeptics |

| Science on Mornings, on triple j | Zan Rowe and Karl Kruszelnicki | Science on Mornings, on triple j is a weekly science segment on Zan Rowe's morning radio show on triple j. The show's mission is to "bring science to the peeps" by answering listener questions with science.[226][238] | ABC triple j | |

| Science On Top | Ed Brown | 10 February 2011 to present | A panel style podcast hosted by Ed Brown and including regular co-hosts Penny Dumsday, Shayne Joseph and Lucas Randall as well as guests and experts discussing science news in an in-depth yet casual style.[239] | Independent |

| The Science Show | Robyn Williams | 1975 to present | The Science Show is a weekly radio program on ABC Radio National which gives unique insights into the latest scientific research and debate.[240] | ABC Radio National |

| The Skeptic Tank | Stefan Sojka and Richard Saunders | 2001 to 2002 | Independent | |

| The Skeptic Zone | Richard Saunders and Stefan Sojka | 26 September 2008 to present | The Skeptic Zone podcast replaced The Tank Vodcast. Though still hosted by Saunders and Sojka, and featuring members of "The Tank", the podcast adopted a new format with clearly defined segments. Episodes usually feature an interview, or several shorter interviews, along with one or more regular segments.[241] Though The Skeptic Zone originated with Saunders, long-time member of the Australian Skeptics, occasionally features members of the latter and their views are often aligned, the podcast is formally independent.[242] | Independent[224][242] |

| Sleek Geeks | Karl Kruszelnicki and Adam Spencer | 26 June 2014 to present | Sleek Geeks is a geeky podcast by Adam Spencer and Dr Karl discussing the latest science news and events.[226][243] | ABC Science |

| Token Skeptic[244] | Kylie Sturgess | 25 December 2009 to present |

The Token Skeptic podcast was the first podcast produced by a solo female presenter in the social sciences category for skepticism on iTunes. In it Kylie Sturgess discusses, among other things, psychology, philosophy, ethics, science, critical thinking, literacy and education. The show includes interviews with international and Australian figures from pop-culture, science fiction, science communication, philosophy and more. The Token Skeptic is also featured on the radio programs Science for Skeptics on the 99.1FM station in Wisconsin, and on Skeptical Sundays for WPRR 1680AM Public Reality Radio in Michigan.[245] Interviews from the Token Skeptic are regularly featured on the Skeptical Inquirer website Curiouser and Curiouser.[246] |

Independent |

| The Tank Vodcast (or The Tank Podcast) | Richard Saunders and Stefan Sojka | 2005 to 2008 | The Skeptic Tank was revived in 2005 as a podcast, and was in 2006 renamed The Tank Podcast. The podcast was produced and hosted by Richard Saunders, with Stefan Sojka as the co-host. The format remained much the same as The Skeptic Tank radio programme, but the podcasting format also made it possible to record segments, or entire episodes, out of the studio.

In 2007 The Tank became a video podcast, and renamed The Tank Vodcast. Reporters for the vodcast include Jayson Cooke, Karen Stollznow, Kylie Sturgess and Michael Wolloghan.[247] |

Independent |

| Unfiltered Thoughts | Jack Scanlan | 26 September 2013 to present | Unfiltered Thoughts is a discussion podcast where Jack Scanlan sits down with young people to discuss their main topic of interest and what they think about issues relating to science and skepticism over coffee in a Melbourne café.[222][248] | Young Australian Skeptics |

Criticisms

There are claims the NSW Skeptics have over-reached in claiming the name 'Australian' skeptics, and also that supporters have no democratic standing, the group being akin to an 'invite only' gentlemen's club, amongst other criticisms about how they conduct themselves generally. [249]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Australian Skeptics 'About us'". Australian Skeptics Inc.. 7 July 2009. http://www.skeptics.com.au/about/.

- ↑ "The Committee for Skeptical Inquiry". CSICOP. http://www.csicop.org/.

- ↑ "Center For Inquiry – About us". http://www.centerforinquiry.net/about.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Hogan, Peter (10 November 2019). "History of Australian Skeptics – Barry Williams and Peter Hogan". Australian Skeptics. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bLzhDYrV6wM&list=PLsudGI1mVCMP3D-YedfDUFzgEvtc_UfgA&index=2&t=0s.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 5.20 5.21 5.22 Mendham, Tim (10 November 2019). "History of Australian Skeptics – Tim Mendham". Australian Skeptics Inc.. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KyqxUnSNXw8&list=PLsudGI1mVCMP3D-YedfDUFzgEvtc_UfgA&index=2.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Smith, Dick (10 November 2019). "History of Australian Skeptics – Dick Smith". Australian Skeptics. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSnQqaQ7MZg&list=PLsudGI1mVCMP3D-YedfDUFzgEvtc_UfgA&index=4.

- ↑ Edwards, Harry (Spring 1994). "A Mighty Oak from a Tiny Acorn Grew". The Skeptic 14 (3). https://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2014%20(1994)%20No%203.pdf. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- ↑ "Phillip Adams AO". Speaker Profile. The Celebrity Speakers Bureau. 2014. http://www.celebrityspeakers.com.au/phillip-adams-ao/.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Smith, Dick (4 June 2009). "Dick Smith On Water Divining". Skeptically Thinking. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Oo41iPeaDiE.

- ↑ Gerrand, Peter; Gerrand, Rob (10 January 2013). "Humanist whose work saved lives". The Age (Victoria, Australia). http://newsstore.theage.com.au/apps/viewDocument.ac?docID=AGE130110111IS77Q44L.

- ↑ "Australian Skeptics 'Another Skeptical Pioneer Dies'". Australian Skeptics Inc.. http://www.skeptics.com.au/2012/10/28/james-gerrand-another-skeptic-pioneer-dies/.

- ↑ "Engineer exploded myths in many fields". Sydney Morning Herald. 9 January 2013. http://www.smh.com.au/comment/obituaries/engineer-exploded-myths-in-many-fields-20130108-2cell.html.

- ↑ "Australian Skeptics". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 1 (1): 4. January 1981. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%201%20Number%201.pdf. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Woods, Laura (22 January 2019). "There's a $100K Reward Going for People Who Prove They're Psychic". Vice Media LLC. https://www.vice.com/en/article/theres-a-dollar100k-reward-going-for-people-who-prove-theyre-psychic/.

- ↑ 15.00 15.01 15.02 15.03 15.04 15.05 15.06 15.07 15.08 15.09 15.10 15.11 Williams, Barry (10 November 2019). "History of Australian Skeptics – Barry Williams and Peter Hogan". Australian Skeptics. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bLzhDYrV6wM&list=PLsudGI1mVCMP3D-YedfDUFzgEvtc_UfgA&index=2&t=0s.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Bryce, Ian (10 November 2019). "History of Australian Skeptics – Ian Bryce". https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NgBj2xfIPQ4&list=PLsudGI1mVCMP3D-YedfDUFzgEvtc_UfgA&index=3.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Roberts, Steve (10 November 2019). "History of Australian Skeptics – Steve Roberts". Australian Skeptics. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mFYZolMPep4&list=PLsudGI1mVCMP3D-YedfDUFzgEvtc_UfgA&index=5.

- ↑ 18.00 18.01 18.02 18.03 18.04 18.05 18.06 18.07 18.08 18.09 18.10 18.11 "Skeptical Groups in Australia". The Skeptic 35 (3): 2. September 2015.

- ↑ "Column 8". The Sydney Morning Herald (Melbourne). 31 May 1995. http://newsstore.theage.com.au/apps/viewDocument.ac?docID=news950531_0055_1116.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 "Australian Skeptics 'Merit Awards'". Australian Skeptics Inc.. 28 November 2011. http://www.skeptics.com.au/features/merit-awards/.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 "Local Skeptical Groups". The Skeptic 35 (3): 63. September 2015.

- ↑ "The 'Fred' Award 2009". http://www.skeptics.com.au/2009/12/01/the-fred-award-2009/.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Mendham, Tim (20 August 2018). "Skeptics award for critical thinking in journalism – Nominations open". https://www.skeptics.com.au/2018/08/20/skeptics-award-for-critical-thinking-in-journalism-nominations-open/.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Buzzard, Dan (5 December 2014). "Australian Skeptic Awards 2014". http://www.danbuzzard.net/journal/australian-skeptic-awards-2014.html.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 "Banned naturopath Barbara O’Neill wins 2025 Bent Spoon" (in English). Australian Skeptics. https://www.skeptics.com.au/banned-naturopath-barbara-oneill-wins-2025-bent-spoon/.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 26.5 26.6 "Merit Awards: Skeptic of the Year". Australian Skeptics. https://www.skeptics.com.au/features/merit-awards/.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 The Skeptic Zone Podcast (8 December 2019). "Episode 582". http://skepticzone.libsyn.com/the-skeptic-zone-581-8december2019.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Mendham, Tim (13 October 2018). "A bad day for Sarah". https://www.skeptics.com.au/2018/10/13/a-bad-day-for-sarah/.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 Mendham, Tim (19 November 2017). "2017 Bent Spoon to NICM; Skeptic of the Year Christine Bayne". https://www.skeptics.com.au/2017-bent-spoon-to-nicm-skeptic-of-the-year-christine-bayne/.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Richard Saunders (27 November 2016). "Skeptic Zone episode 423". skepticzone.libsyn.com (Podcast). 38–44 minutes in. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ↑ "#374". http://ec.libsyn.com/p/f/3/5/f351ab586d3ccf32/the_skeptic_zone_376_160103.mp3?d13a76d516d9dec20c3d276ce028ed5089ab1ce3dae902ea1d06cd8537d4cc5fecb0&c_id=10615405.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 "Around the traps...". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 34 (4): 5. December 2014.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 "Skeptic of the Year". The Skeptic 33 (4): 6. December 2013. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2033%20(2013)%20No%204.pdf. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 "Skeptics' Awards 2012... And the winner is". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 32 (4): 14. December 2012. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2032%20(2012)%20No%204.pdf. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ "2012 Bent Spoon Award". Australian Skeptics Inc. http://www.skeptics.com.au/2012/12/04/2012-bent-spoon-award/.

- ↑ "Australian Skeptics National Convention 2014". Australian Skeptics Inc. http://convention.skeptics.com.au/adam-vanlangenberg/.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 "Bent Spoon to RMIT; Skeptic of the Year to Loretta Marron". Australian Skeptics Inc.. http://www.skeptics.com.au/2011/11/20/bent-spoon-to-rmit-soty-to-loretta-marron/.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 "Around the traps... awards". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 31 (4): 5. December 2011. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2031%20(2011)%20No%204.pdf. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ "Ken Harvey taken to court". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 31 (2): 6. December 2011. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2031%20(2011)%20No%202.pdf. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ↑ "The SensaSlim Saga". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 31 (3): 16. December 2011. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2031%20(2011)%20No%203.pdf. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ↑ "Onward...". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 30 (4): 4. December 2010. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2030%20(2010)%20No%204.pdf. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 "Skeptics' Awards... And the winner is". The Skeptic 30 (4): 12. December 2010. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2030%20(2010)%20No%204.pdf. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ↑ Plait, Phil. "Australian skeptics cheer David and Toni McCaffery". Discover Magazine. http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/badastronomy/2009/12/02/australian-skeptics-cheer-david-and-toni-mccaffery/.

- ↑ "The 'Fred' Award 2009". Australian Skeptics Inc. http://www.skeptics.com.au/2009/12/01/the-fred-award-2009/.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 "And the Winners are...". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics Inc.) 29 (4): 9. December 2009. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2029%20(2009)%20No%204.pdf. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ↑ "Merit Awards: Skeptic of the Year". Australian Skeptics. 28 November 2011. https://www.skeptics.com.au/features/merit-awards/.

- ↑ "Australian Skeptic of the Year 2014". 29 November 2014. http://reasonablehank.com/2014/11/29/australian-skeptic-of-the-year-2014/.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 "University of Sydney Professor awarded Australia's biggest Skeptic". University of Sydney. http://sydney.edu.au/medicine/news/news/2013/Dec/skeptic-of-the-year.php.

- ↑ "Professor Simon Chapman AM". http://preventioncentre.org.au/our-people/chief-investigators/professor-simon-chapman/.

- ↑ "Simon Chapman". The Conversation. 23 May 2011. https://theconversation.com/profiles/simon-chapman-1831.

- ↑ "What if Sydney University's complementary medicine research shows it's useless?". The Conversation. 27 May 2015. https://theconversation.com/what-if-sydney-universitys-complementary-medicine-research-shows-its-useless-42415.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 "Testing times for medical science". Ockham's Razor Podcast with Robyn Williams. 9 December 2012. ABC Radio National. Archived from the original on 21 August 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 "Loretta Marron wins Order of Australia". http://www.skeptics.com.au/2014/01/25/loretta-marron-wins-order-of-australia/.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 "The Skeptic Zone Episode 276". The Skeptic Zone. 2 Feb 2014. http://skepticzone.libsyn.com/webpage?search=loretta+marron&Submit=Search.

- ↑ "Loretta Marron – Exposing CAM". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 32 (4): 13. December 2012. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2032%20(2012)%20No%204.pdf. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3 56.4 56.5 56.6 56.7 Mongia, Gurmukh (March 2013). "Bent Spoon Awarded to Homeopath". Skeptical Inquirer 37 (2): 7–8.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 "Australian Skeptics honor the Best and the Worst of the Year". http://doubtfulnews.com/2011/11/australian-skeptics-honor-the-best-and-the-worst-of-the-year/.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 "About FSM Association and Executive". http://www.scienceinmedicine.org.au/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=119:association-and-executive&catid=68:association-and-executive&Itemid=159.

- ↑ "The end of the world news". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 31 (4): 4. December 2011. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2031%20(2011)%20No%204.pdf. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 "Convention Round-up". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 27 (4): 7. Summer 2007. http://www.skeptics.com.au/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2027%20(2007)%20No%204.pdf. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ "Karl S. Kruszelnicki". 20 March 2008. http://www.abc.net.au/profiles/content/s2193276.htm.

- ↑ "About Karl". http://drkarl.com/about-karl/.

- ↑ "Karl Kruszelnicki (Dr Karl)". RiAUS. http://riaus.org.au/people/karl-kruszelnicki/.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 "Annual Skeptics Awards". The Skeptic 26 (4): 9. Summer 2006. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2026%20(2006)%20No%204.pdf. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 "Convention Round-up". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 24 (4): 6. Summer 2004. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2024%20(2004)%20No%204.pdf. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ "Paul Willis". RiAUS. http://riaus.org.au/article-author/paul-willis/.

- ↑ "Skeptic of the Year". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 22 (4): 12. Summer 2002. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2022%20(2002)%20No%204.pdf. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 "Australian Skeptics awards". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 20 (4): 28. Summer 2000. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2020%20(2000)%20No%204.pdf. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 "Worthy recipients of Skeptics' awards named". The Skeptic 19 (4): 10. Summer 1999. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2019%20(1999)%20No%204.pdf. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ↑ "Professor Michael Archer". University of NSW. http://www.bees.unsw.edu.au/michael-archer.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 "Awards and music at annual dinner". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 18 (4): 9. Summer 1998. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2018%20(1998)%20No%204.pdf. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 Williams, Barry (Spring 1997). "1997 Convention a great success". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 17 (3): 5. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2017%20(1997)%20No%203.pdf. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 73.2 Williams, Barry (Summer 1996). "Convention Notes". The Skeptic 16 (4): 14. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2016%20(1996)%20No%204.pdf. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ↑ Australian Skeptics Inc. (28 November 2011). "The Barry Williams Award for Skeptical Journalism". https://www.skeptics.com.au/features/merit-awards/.

- ↑ "The Skeptic Zone Episode 358". The Skeptic Zone. 30 Aug 2015. http://skepticzone.libsyn.com/the-skeptic-zone-358-30aug2015.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 76.2 Williams, Barry. "History of the Bent Spoon Award". Australian Skeptics. http://www.skeptics.com.au/features/bent-spoon/history-bent-spoon/.

- ↑ "Australian Skeptics Awards 2007". The Science Show with Robyn Williams. 1 December 2007. ABC Radio National. Archived from the original on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 78.2 78.3 "Bad slot for mumbo jumbo". The Australian. 29 November 2006. http://www.theaustralian.com.au/archive/news/bad-slot-for-mumbo-jumbo/story-e6frg8gf-1111112600080.

- ↑ "Ken Ring coverage wins skeptics' Bent Spoon award". The New Zealand Herald. 12 August 2011. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=10744642.

- ↑ "Cancer Council WA wins 2024 Skeptics’ Bent Spoon - Australian Skeptics Inc" (in en-AU). 2024-11-26. https://www.skeptics.com.au/cancer-council-wa-wins-2024-skeptics-bent-spoon/.

- ↑ "Walkley winner Coulthart wins 2023 Bent Spoon". Australian Skeptics. 8 December 2023. https://www.skeptics.com.au/walkley-winner-coulthart-wins-2023-bent-spoon/. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ↑ "COVID-denying fake doctor who handed out 1200 exemptions fined $25,000". Brisbane Times. 20 July 2022. https://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/national/queensland/covid-denying-fake-doctor-who-handed-out-1200-exemptions-fined-25-000-20220720-p5b2zg.html. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ↑ "Non-doctor Maria Carmela Pau wins 2022 Bent Spoon". 12 December 2022. https://www.skeptics.com.au/2022/12/12/non-doctor-maria-carmela-pau-wins-2022-bent-spoon/. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ↑ "MP Craig Kelly wins 2021 Bent Spoon". Australian Skeptics. https://www.skeptics.com.au/2021/11/22/mp-craig-kelly-wins-2021-bent-spoon/.

- ↑ "The Bent Spoon Award: Past Winners". Australian Skeptics. 12 July 2009. https://www.skeptics.com.au/features/bent-spoon/.

- ↑ Mitchell, Georgina. "Pete Evans given award which recognises 'quackery'". Sydney Morning Herald. http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/pete-evans-given-award-which-recognises-quackery-20151017-gkbq4i.html#ixzz3opfk6DCW.

- ↑ "Bent Spoon goes to CSIRO Head". Australian Skeptics Inc.. http://www.skeptics.com.au/2014/12/04/bent-spoon-to-csiro-head/.

- ↑ "Skeptics Award Bent Spoon to New CSIRO Chief". Australasian Science January/February 2015. January 2015. http://www.australasianscience.com.au/article/issue-januaryfebruary-2015/skeptics-award-bent-spoon-new-csiro-chief.html. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ↑ Manning, Paddy (9 July 2016). "The Science Show – CSIRO chief retains award for dodgy science". RN. ABC. http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/scienceshow/csiro-chief-retains-award-for-dodgy-science/7581260.

- ↑ "Chiropractors win joint Bent Spoon". Australian Skeptics Inc.. http://www.skeptics.com.au/2013/11/25/chiropractors-win-joint-bent-spoon/.

- ↑ "Chiropractors win joint Bent Spoon". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 33 (4): 6. December 2013. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2033%20(2013)%20No%204.pdf. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ Smith, Bridie (3 December 2012). "Skeptics confer spoon accolade". The Age (Victoria, Australia). http://www.theage.com.au/national/skeptics-confer-spoon-accolade-20121202-2ap2r.html.

- ↑ "Australian Bent Spoon award goes to Homeopathy Plus". http://doubtfulnews.com/2012/12/australian-bent-spoon-award-goes-to-homeopathy-plus/.

- ↑ "2012 Bent Spoon Award/". Australian Skeptics Inc.. http://www.skeptics.com.au/2012/12/04/2012-bent-spoon-award/.

- ↑ "Meryl Dorey and the AVN win 2009 Bent Spoon". Australian Skeptics. 29 November 2009. http://www.skeptics.com.au/2009/11/29/meryl-dorey-and-the-avn-win-2009-bent-spoon/.

- ↑ Gooch, Peter. "Meryl Dorey on her 'Bent Spoon Award'". ABC Radio. http://blogs.abc.net.au/queensland/2009/12/meryl-dorey-on-her-bent-spoon-award.html.

- ↑ "Meryl Dorey wins the Bent Spoon". http://youngausskeptics.com/2009/11/meryl-dorey-wins-the-bent-spoon/.

- ↑ Mcmillan, Mel (1 December 2009). "Skeptics hand out Bent Spoon". The Northern Star. http://www.northernstar.com.au/news/anti-vaccine-network-gets-dubious-award/417765/.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 "Convention Roundup". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 28 (4): 28. Summer 2008. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2028%20(2008)%20No%204.pdf. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ↑ "Mortar, pestle and bent spoon". 6minutes.com.au. Cirrus Media. 30 November 2006. http://www.6minutes.com.au/articles/z1/view.asp?id=51085.

- ↑ Williams, Barry (Summer 2005). "Massaging the Message". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 25 (3): 3. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2025%20(2005)%20No%203.pdf. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ↑ "Bent Spoon". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 23 (3): 8. Spring 2003. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2023%20(2003)%20No%203.pdf. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ↑ "Award Winners". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 22 (4): 11. Summer 2002. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2022%20(2002)%20No%204.pdf. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ↑ "Bent Spoon Winner". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 21 (4): 7. Summer 2001. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2021%20(2001)%20No%204.pdf. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ↑ Rodrigues, Marilyn (8 December 2002). "Conversation: Michael Willesee, journalist and producer -…the presence of Jesus". The Catholic Weekly. http://www.catholicweekly.com.au/02/dec/8/16.html.

- ↑ Ackland, Richard (21 February 2014). "As it happens, crime does pay ... and it always will". The Canberra Times. http://www.canberratimes.com.au/comment/richard-ackland-as-it-happens-crime-does-pay--and-it-always-will-20140220-333yv.html.

- ↑ "Stay In Touch: Visionaries". The Sydney Morning Herald (Melbourne). 6 December 1995. http://newsstore.theage.com.au/apps/viewDocument.ac?docID=news950612_0001_1520.

- ↑ "Bent Spoon Award for 1995". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 15 (3): 27. Spring 1995. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2015%20(1995)%20No%203.pdf. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ↑ Williams, Barry (Spring 1994). "A G Wins B S". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 14 (3): 9. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2014%20(1994)%20No%203.pdf. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ↑ Walker, David (7 July 1993). "Seven earns a bent spoon". The Age (Victoria, Australia). http://newsstore.theage.com.au/apps/viewDocument.ac?docID=news930707_0197_0967.

- ↑ Warburton, Annie (Spring 1993). "Kinesiology on the Wireless". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 13 (3): 29. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2013%20(1993)%20No%203.pdf. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ↑ Williams, Barry (Spring 1992). "Bent Spoon Award". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 12 (3): 11. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2012%20(1992)%20No%203.pdf. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ↑ "Bent Spoon Winner". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 11 (3): 91. Spring 1991. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2011%20(1991)%20No%203.pdf. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ↑ 114.0 114.1 114.2 114.3 114.4 114.5 114.6 114.7 Williams, Barry (Autumn 1991). "Bent Spoon Revisited". The Skeptic 11 (1): 33–34. http://www.skeptics.com.au/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2011%20(1991)%20No%201.pdf.

- ↑ "The Second Coming – Psychics". The Skeptic, All the Best from 1986 to 1990. http://www.skeptics.com.au/magazine/The%20Second%20Coming%20-%201986%20to%201990%20collection%20-%20Psychics.pdf.

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 116.2 116.3 "The Second Coming – Skepticism". The Skeptic, All the Best from 1986 to 1990. http://www.skeptics.com.au/magazine/The%20Second%20Coming%20-%201986%20to%201990%20collection%20-%20Skepticism.pdf.

- ↑ 117.0 117.1 West, Andrew (30 March 1988). "The 1988 Bent Spoon award is up for grabs". The Age (Melbourne). http://newsstore.theage.com.au/apps/viewDocument.ac?docID=news880330_0255_7104.

- ↑ "Brock Impresses the Sceptics". The Sydney Morning Herald. 20 April 1987. https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1301&dat=19870420&id=OnZWAAAAIBAJ&sjid=tOQDAAAAIBAJ&pg=5646,3152183&hl=en.

- ↑ "The Second Coming – Pseudoscience". The Skeptic, All the Best from 1986 to 1990. http://www.skeptics.com.au/magazine/The%20Second%20Coming%20-%201986%20to%201990%20collection%20-%20Pseudoscience.pdf.

- ↑ 120.0 120.1 Williams, Barry. "In the Beginning". The Skeptic, the First 5 Years. http://www.skeptics.com.au/magazine/In%20the%20Beginning%20-%20the%20first%20five%20years.pdf.

- ↑ Andy Burns (15 December 2012). "Minister orders anti-vaccination group to change its name". Herald Sun. http://www.heraldsun.com.au/news/victoria/minister-orders-anti-vaccination-group-to-change-its-name/story-e6frf7kx-1226537155195.

- ↑ "Anti-vaccine group must change 'misleading' name". Northern Star. 17 December 2012. http://www.northernstar.com.au/news/anti-vaccine-group-must-change-misleading-name/1685224/.

- ↑ "Anti-vaccine set forced to fess up". David Penberthy. 20 December 2012. http://www.adelaidenow.com.au/news/opinion/david-penberthy-anti-vaccine-set-forced-to-fess-up/story-e6freall-1226541363953.

- ↑ Foschia, Liz. "Australian Vaccination Network changes name to reflect sceptical stance". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-03-11/nsw-anti-vaccination-group-changes-its-name-after-complaints/5312910. "The Australian Vaccination Network has changed its name to one that more clearly reflects its anti-vaccination views."

- ↑ 125.0 125.1 "Australian Skeptics 'The $100000 Challenge'". Australian Skeptics Inc.. 12 July 2009. http://www.skeptics.com.au/features/prize/.

- ↑ Robson, Lou (3 July 2008). "Witches brave the fires of scepticism". The Age (Victoria, Australia). http://www.theage.com.au/news/tv--radio/witches-brave-scepticism/2008/07/02/1214950817986.html.

- ↑ "Go with Australian Skeptics". http://www.undeceivingourselves.org/A-gowi.htm.

- ↑ "Who We Are". Australian Skeptics Inc.. 20 November 2016. https://www.skeptics.com.au/about/us/.

- ↑ "Macquarie University Psychology Staff". Macquarie University. http://humansciences.mq.edu.au/psychology/psychology_staff/psychology_academic_staff/trevor_case.

- ↑ "Amanda Barnier". The Conversation. 22 November 2013. https://theconversation.com/profiles/amanda-barnier-109795.

- ↑ "Profile: Amanda Barnier". The Science Show with Robyn Williams. 14 February 1998. ABC Radio National. Archived from the original on 11 January 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ Williams, Barry (Summer 1997). "Eureka winners announced". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 17 (4): 6. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2017%20(1997)%20No%204.pdf. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ "1999 Eureka Prize winners announced". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 19 (2): 6. Winter 1999. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2019%20(1999)%20No%202.pdf. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ "Eureka Prize winners". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 20 (2): 6. Winter 2000. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2020%20(2000)%20No%202.pdf. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ "Tim van Gelder". The Conversation. 21 June 2012. https://theconversation.com/profiles/tim-van-gelder-10515.

- ↑ "Lifeboat Foundation Advisory Board". Lifeboat Foundation. http://lifeboat.com/ex/bios.tim.van.gelder.

- ↑ "MAP14 Master Class Series". The University of Melbourne. 11 November 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8cHPVrz8qAA.

- ↑ "Eureka Prizes Reward Science Excellence". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 21 (2): 7. Winter 2001. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2021%20(2001)%20No%202.pdf. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ "The University of Adelaide News and Events". The University of Adelaide. https://www.adelaide.edu.au/news/news380.html.

- ↑ "RiAUS People". Research Institute of Australia. http://riaus.org.au/people/rob-morrison/.

- ↑ "Nature Foundation SA Our People". Nature Foundation SA. http://www.naturefoundation.org.au/about-us/our-people/.

- ↑ "Eureka Prize Winners". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 22 (3): 11. Spring 2002. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2022%20(2002)%20No%203.pdf. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ "Eureka Prizes 2003". The Science Show with Robyn Williams. 16 August 2003. ABC Radio National. Archived from the original on 11 January 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ "Eureka Winners Announced". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 23 (3): 6. Spring 2003. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2023%20(2003)%20No%203.pdf. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ↑ "Eureka Prizes Set New Records". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 24 (3): 6. Spring 2004. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2024%20(2004)%20No%203.pdf. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ "Prestigious Eureka science prizes awarded". ABC. 9 August 2005. http://www.abc.net.au/news/2005-08-09/prestigious-eureka-science-prizes-awarded/2077498.

- ↑ "Amanda Wilson". The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/profiles/amanda-wilson-3386.

- ↑ "Eureka full winners list". 10 August 2005. http://www.smh.com.au/news/business/eureka-full-winners-list/2005/08/09/1123353317596.html.

- ↑ "Eureka Winner". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 25 (3): 8. Summer 2005. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2025%20(2005)%20No%203.pdf. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ↑ "Skeptics World Convention". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 20 (3): 37. Spring 2000. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2020%20(2000)%20No%203.pdf. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ "Martin Bridgstock". CFI. http://www.csicop.org/author/marginbridgstock.

- ↑ "Dr Martin Bridgstock The Skeptical Eye". http://www.embiggenbooks.com/blogs/embiggen-books/6066776-dr-martin-bridgstock.

- ↑ "The 'Token Skeptic' at the Rise of Atheism—Global Atheist Convention, Melbourne, Australia". CFI. 31 March 2010. http://www.csicop.org/specialarticles/show/the_token_skeptic_at_the_rise_of_atheism_global_atheist_convention/.

- ↑ "ThePhilosopher's Zone with Joe Gelonesi". ABC Radio National. 19 December 2006. http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/philosopherszone/seasonal-skepticism/3387416#transcript.

- ↑ Peter Ellerton. "Critical Thinking Project". The University of Queensland. http://www.ctp.uq.edu.au/content/peter-ellerton.

- ↑ "Peter Ellerton". The Conversation. 18 April 2012. https://theconversation.com/profiles/peter-ellerton-8574.

- ↑ "Critical Thinking in Schools". The Skeptic (Australian Skeptics) 28 (11): 28. Summer 2008. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2028%20(2008)%20No%204.pdf. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ↑ "Young Australian Skeptics". http://youngausskeptics.com.

- ↑ "Brisbane Skeptics Society". Brisbane Skeptics Society. http://www.brisbaneskeptics.org/about/.

- ↑ "Perth Skeptics". https://perthskeptics.com.au/.

- ↑ "Perth Skeptics". https://www.meetup.com/Perth_Skeptics.

- ↑ Farley, Tim (March 2015). "Skeptical Anniversaries". Skeptical Inquirer 39 (2): 66.

- ↑ "Skepticon 2019". Victorian Skeptics. https://skepticon.org.au.

- ↑ "Skepticon: Australian Skeptics National Convention" (in en-GB). 2018-04-12. https://www.skeptics.com.au/event/national-convention/.

- ↑ "Australian Skeptics Convention 2017". https://www.skeptics.com.au/event/skeptics-convention-2017/.

- ↑ "2016 Convention latest". 2016-06-01. https://vicskeptics.wordpress.com/2016/06/01/2016-convention-latest/.

- ↑ "Australian Skeptics National Convention MMXV". Brisbane Skeptic Society. http://convention.brisbaneskeptics.org.

- ↑ "2015 Skeptics Convention Speakers". The Skeptic 35 (2): 7. June 2015.

- ↑ "Sydney 2014 30th Skeptics National Convention". The Skeptic 34 (1): 5. March 2014. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2034%20(2014)%20No%201.pdf. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

- ↑ "Australian Skeptics National Convention 2013". Australian Skeptics Inc. http://www.skeptics.com.au/2013/04/27/australian-skeptics-national-convention-2013/.

- ↑ "Randi for 2012 Melbourne – November 30 to December 2 National Convention". The Skeptic 32 (1): 7. March 2012. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2032%20(2012)%20No%201.pdf. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ↑ "Celebrating Australian Skeptics 30th Anniversary". The Skeptic 30 (1): 63. March 2010. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2030%20(2010)%20No%201.pdf. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ↑ "Briskepticon '09". The Skeptic 29 (3): 8. September 2009. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2029%20(2009)%20No%203.pdf. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ↑ "National Convention". The Skeptic 28 (2): 65. Winter 2008. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2028%20(2008)%20No%201.pdf. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ↑ "Australian Skeptics National Convention". The Skeptic 27 (3): 64. Spring 2007. http://www.skeptics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/magazine/The%20Skeptic%20Volume%2027%20(2007)%20No%203.pdf. Retrieved 20 September 2015.