CERN

Topic: Organization

From HandWiki - Reading time: 40 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 40 min

Organisation européene pour la recherche nucléaire | |

| |

CERN's main site in Meyrin, Switzerland, looking towards the French border | |

States with full CERN membership | |

| Formation | 29 September 1954[1] |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Meyrin, Geneva, Switzerland [ ⚑ ] : 46°14′03″N 6°03′10″E / 46.23417°N 6.05278°E |

Membership | Full members (23):

Associate members (10):

|

Official languages | English and French |

Council President | Eliezer Rabinovici[2] |

Director-General | Fabiola Gianotti |

Budget (2022) | 1405m CHF[3] |

| Website | home |

The European Organization for Nuclear Research, known as CERN (/sɜːrn/; French pronunciation: [sɛʁn]; Conseil européen pour la Recherche nucléaire), is an intergovernmental organization that operates the largest particle physics laboratory in the world. Established in 1954, it is based in Meyrin, western suburb of Geneva, on the France–Switzerland border. It comprises 23 member states.[4] Israel, admitted in 2013, is the only non-European full member.[5][6] CERN is an official United Nations General Assembly observer.[7]

The acronym CERN is also used to refer to the laboratory; in 2019, it had 2,660 scientific, technical, and administrative staff members, and hosted about 12,400 users from institutions in more than 70 countries.[8] In 2016, CERN generated 49 petabytes of data.[9]

CERN's main function is to provide the particle accelerators and other infrastructure needed for high-energy physics research – consequently, numerous experiments have been constructed at CERN through international collaborations. CERN is the site of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the world's largest and highest-energy particle collider.[10] The main site at Meyrin hosts a large computing facility, which is primarily used to store and analyze data from experiments, as well as simulate events. As researchers require remote access to these facilities, the lab has historically been a major wide area network hub. CERN is also the birthplace of the World Wide Web.[11][12]

History

The convention establishing CERN[14] was ratified on 29 September 1954 by 12 countries in Western Europe.[15] The acronym CERN originally represented the French words for Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire ('European Council for Nuclear Research'), which was a provisional council for building the laboratory, established by 12 European governments in 1952. During these early years, the council worked at the University of Copenhagen under the direction of Niels Bohr before moving to its present site near Geneva. The acronym was retained for the new laboratory after the provisional council was dissolved, even though the name changed to the current Organisation Européenne pour la Recherche Nucléaire ('European Organization for Nuclear Research') in 1954.[16][17] According to Lew Kowarski, a former director of CERN, when the name was changed, the abbreviation could have become the awkward OERN,[18] and Werner Heisenberg said that this could "still be CERN even if the name is [not]".[19]

CERN's first president was Sir Benjamin Lockspeiser. Edoardo Amaldi was the general secretary of CERN at its early stages when operations were still provisional, while the first Director-General (1954) was Felix Bloch.[20]

The laboratory was originally devoted to the study of atomic nuclei, but was soon applied to higher-energy physics, concerned mainly with the study of interactions between subatomic particles. Therefore, the laboratory operated by CERN is commonly referred to as the European laboratory for particle physics (Laboratoire européen pour la physique des particules), which better describes the research being performed there.[citation needed]

Founding members

At the sixth session of the CERN Council, which took place in Paris from 29 June to 1 July 1953, the convention establishing the organization was signed, subject to ratification, by 12 states. The convention was gradually ratified by the 12 founding Member States: Belgium, Denmark, France, the Federal Republic of Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and Yugoslavia.[21]

Scientific achievements

Several important achievements in particle physics have been made through experiments at CERN. They include:

- 1973: The discovery of neutral currents in the Gargamelle bubble chamber;[22]

- 1983: The discovery of W and Z bosons in the UA1 and UA2 experiments;[22]

- 1989: The determination of the number of light neutrino families at the Large Electron–Positron Collider (LEP) operating on the Z boson peak;[23]

- 1995: The first creation of antihydrogen atoms in the PS210 experiment;[24][25]

- 1995–2005: Precision measurement of the Z lineshape,[26][27] based predominantly on LEP data collected on the Z resonance from 1990 to 1995;

- 1999: The discovery of direct CP violation in the NA48 experiment;[28]

- 2000: The Heavy Ion Programme discovered a new state of matter, the Quark Gluon Plasma.[29]

- 2010: The isolation of 38 atoms of antihydrogen;[30][31]

- 2011: Maintaining antihydrogen for over 15 minutes;[32][33]

- 2012: A boson with mass around 125 GeV/c2 consistent with the long-sought Higgs boson.[34][35][36]

In September 2011, CERN attracted media attention when the OPERA Collaboration reported the detection of possibly faster-than-light neutrinos.[37] Further tests showed that the results were flawed due to an incorrectly connected GPS synchronization cable.[38]

The 1984 Nobel Prize for Physics was awarded to Carlo Rubbia and Simon van der Meer for the developments that resulted in the discoveries of the W and Z bosons.[39] The 1992 Nobel Prize for Physics was awarded to CERN staff researcher Georges Charpak "for his invention and development of particle detectors, in particular the multiwire proportional chamber". The 2013 Nobel Prize for Physics was awarded to François Englert and Peter Higgs for the theoretical description of the Higgs mechanism in the year after the Higgs boson was found by CERN experiments.

Computer science

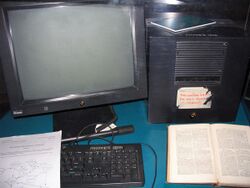

CERN pioneered the introduction of Internet technology, beginning in the early 1980s. This played an influential role in the adoption of the TCP/IP in Europe (see Protocol Wars).[40]

The World Wide Web began as a project at CERN initiated by Tim Berners-Lee in 1989. This stemmed from his earlier work on a database named ENQUIRE. Robert Cailliau became involved in 1990.[41][42][43][44] Berners-Lee and Cailliau were jointly honoured by the Association for Computing Machinery in 1995 for their contributions to the development of the World Wide Web.[45] A copy of the original first webpage, created by Berners-Lee, is still published on the World Wide Web Consortium's website as a historical document.[46]

Based on the concept of hypertext, the project was designed to facilitate the sharing of information between researchers. The first website was activated in 1991. On 30 April 1993, CERN announced that the World Wide Web would be free to anyone. It became the dominant way through which most users interact with the Internet.[47][48]

More recently, CERN has become a facility for the development of grid computing, hosting projects including the Enabling Grids for E-sciencE (EGEE) and LHC Computing Grid. It also hosts the CERN Internet Exchange Point (CIXP), one of the two main internet exchange points in Switzerland. As of 2022[update], CERN employs ten times more engineers and technicians than research physicists.[49]

Particle accelerators

Current complex

CERN operates a network of seven accelerators and two decelerators, and some additional small accelerators. Each machine in the chain increases the energy of particle beams before delivering them to experiments or to the next more powerful accelerator (the decelerators naturally decrease the energy of particle beams before delivering them to experiments or further accelerators/decelerators). Before an experiment is able to use the network of accelerators, it must be approved by the various Scientific Committees of CERN.[50] Currently (as of 2022) active machines are the LHC accelerator and:

- The LINAC 3 linear accelerator generating low energy particles. It provides heavy ions at 4.2 MeV/u for injection into the Low Energy Ion Ring (LEIR).[51]

- The Low Energy Ion Ring (LEIR) accelerates the ions from the ion linear accelerator LINAC 3, before transferring them to the Proton Synchrotron (PS). This accelerator was commissioned in 2005, after having been reconfigured from the previous Low Energy Antiproton Ring (LEAR).[52][53]

- The Linac4 linear accelerator accelerates negative hydrogen ions to an energy of 160 MeV. The ions are then injected to the Proton Synchrotron Booster (PSB) where both electrons are then stripped from each of the hydrogen ions and thus only the nucleus containing one proton remains. The protons are then used in experiments or accelerated further in other CERN accelerators. Linac4 serves as the source of all proton beams for CERN experiments.[54]

- The Proton Synchrotron Booster increases the energy of particles generated by the proton linear accelerator before they are transferred to the other accelerators.[55]

- The 28 GeV Proton Synchrotron (PS), built during 1954–1959 and still operating as a feeder to the more powerful SPS and to many of CERN's experiments.[56]

- The Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS), a circular accelerator with a diameter of 2 kilometres built in a tunnel, which started operation in 1976. It was designed to deliver an energy of 300 GeV and was gradually upgraded to 450 GeV. As well as having its own beamlines for fixed-target experiments (currently COMPASS and NA62), it has been operated as a proton–antiproton collider (the SppS collider), and for accelerating high energy electrons and positrons which were injected into the Large Electron–Positron Collider (LEP). Since 2008, it has been used to inject protons and heavy ions into the Large Hadron Collider (LHC).[57][58][59]

- The On-Line Isotope Mass Separator (ISOLDE), which is used to study unstable nuclei. The radioactive ions are produced by the impact of protons at an energy of 1.0–1.4 GeV from the Proton Synchrotron Booster. It was first commissioned in 1967 and was rebuilt with major upgrades in 1974 and 1992.[60]

- The Antiproton Decelerator (AD), which reduces the velocity of antiprotons to about 10% of the speed of light for research of antimatter.[61] The AD machine was reconfigured from the previous Antiproton Collector (AC) machine.[62]

- The Extra Low Energy Antiproton ring (ELENA), which takes antiprotons from AD and decelerates them into low energies (speeds) for use in antimatter experiments.

- The AWAKE experiment, which is a proof-of-principle plasma wakefield accelerator.[63][64]

- The CERN Linear Electron Accelerator for Research (CLEAR) accelerator research and development facility.[65][66]

Large Hadron Collider

Many activities at CERN currently involve operating the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) and the experiments for it. The LHC represents a large-scale, worldwide scientific cooperation project.[67]

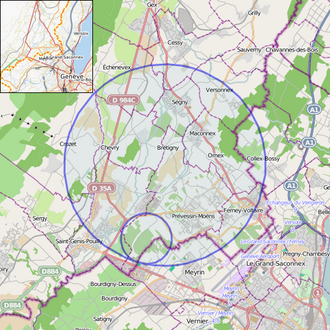

The LHC tunnel is located 100 metres underground, in the region between Geneva International Airport and the nearby Jura mountains. The majority of its length is on the French side of the border. It uses the 27 km circumference circular tunnel previously occupied by the Large Electron–Positron Collider (LEP), which was shut down in November 2000. CERN's existing PS/SPS accelerator complexes are used to pre-accelerate protons and lead ions which are then injected into the LHC.

Eight experiments (CMS,[68] ATLAS,[69] LHCb,[70] MoEDAL,[71] TOTEM,[72] LHCf,[73] FASER[74] and ALICE[75]) are located along the collider; each of them studies particle collisions from a different aspect, and with different technologies. Construction for these experiments required an extraordinary engineering effort. For example, a special crane was rented from Belgium to lower pieces of the CMS detector into its cavern, since each piece weighed nearly 2,000 tons. The first of the approximately 5,000 magnets necessary for construction was lowered down a special shaft at 13:00 GMT on 7 March 2005.

The LHC has begun to generate vast quantities of data, which CERN streams to laboratories around the world for distributed processing (making use of a specialized grid infrastructure, the LHC Computing Grid). During April 2005, a trial successfully streamed 600 MB/s to seven different sites across the world.

The initial particle beams were injected into the LHC August 2008.[76] The first beam was circulated through the entire LHC on 10 September 2008,[77] but the system failed 10 days later because of a faulty magnet connection, and it was stopped for repairs on 19 September 2008.

The LHC resumed operation on 20 November 2009 by successfully circulating two beams, each with an energy of 3.5 teraelectronvolts (TeV). The challenge for the engineers was then to line up the two beams so that they smashed into each other. This is like "firing two needles across the Atlantic and getting them to hit each other" according to Steve Myers, director for accelerators and technology.

On 30 March 2010, the LHC successfully collided two proton beams with 3.5 TeV of energy per proton, resulting in a 7 TeV collision energy. However, this was just the start of what was needed for the expected discovery of the Higgs boson. When the 7 TeV experimental period ended, the LHC revved to 8 TeV (4 TeV per proton) starting March 2012, and soon began particle collisions at that energy. In July 2012, CERN scientists announced the discovery of a new sub-atomic particle that was later confirmed to be the Higgs boson.[78]

In March 2013, CERN announced that the measurements performed on the newly found particle allowed it to conclude that it was a Higgs boson.[79] In early 2013, the LHC was deactivated for a two-year maintenance period, to strengthen the electrical connections between magnets inside the accelerator and for other upgrades.

On 5 April 2015, after two years of maintenance and consolidation, the LHC restarted for a second run. The first ramp to the record-breaking energy of 6.5 TeV was performed on 10 April 2015.[80][81] In 2016, the design collision rate was exceeded for the first time.[82] A second two-year period of shutdown begun at the end of 2018.[83][84]

Accelerators under construction

As of October 2019, the construction is on-going to upgrade the LHC's luminosity in a project called High Luminosity LHC (HL–LHC). This project should see the LHC accelerator upgraded by 2026 to an order of magnitude higher luminosity.[85]

As part of the HL–LHC upgrade project, also other CERN accelerators and their subsystems are receiving upgrades. Among other work, the LINAC 2 linear accelerator injector was decommissioned and replaced by a new injector accelerator, the LINAC4.[86]

Decommissioned accelerators

- The original linear accelerator LINAC 1. Operated 1959–1992.[87]

- The LINAC 2 linear accelerator injector. Accelerated protons to 50 MeV for injection into the Proton Synchrotron Booster (PSB). Operated 1978–2018.[88]

- The 600 MeV Synchro-Cyclotron (SC) which started operation in 1957 and was shut down in 1991. Was made into a public exhibition in 2012–2013.[89][90]

- The Intersecting Storage Rings (ISR), an early collider built from 1966 to 1971 and operated until 1984.[91][92]

- The Super Proton–Antiproton Synchrotron (SppS), operated 1981–1991.[93] A modification of Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS) to operate as a proton-antiproton collider.

- The Large Electron–Positron Collider (LEP), which operated 1989–2000 and was the largest machine of its kind, housed in a 27 km-long circular tunnel which now houses the Large Hadron Collider.[94][95]

- The LEP Pre-Injector (LPI) accelerator complex,[96] consisting of two accelerators, a linear accelerator called LEP Injector Linac (LIL; itself consisting of two back-to-back linear accelerators called LIL V and LIL W) and a circular accelerator called Electron Positron Accumulator (EPA).[97] The purpose of these accelerators was to inject positron and electron beams into the CERN accelerator complex (more precisely, to the Proton Synchrotron), to be delivered to LEP after many stages of acceleration. Operational 1987–2001; after the shutdown of LEP and the completion of experiments that were directly fed by the LPI, the LPI facility was adapted to be used for the CLIC Test Facility 3 (CTF3).[98]

- The Low Energy Antiproton Ring (LEAR) was commissioned in 1982. LEAR assembled the first pieces of true antimatter, in 1995, consisting of nine atoms of antihydrogen.[99] It was closed in 1996, and superseded by the Antiproton Decelerator. The LEAR apparatus itself was reconfigured into the Low Energy Ion Ring (LEIR) ion booster.[52]

- The Antiproton Accumulator (AA), built 1979–1980, operations ended in 1997 and the machine was dismantled. Stored antiprotons produced by the Proton Synchrotron (PS) for use in other experiments and accelerators (for example the ISR, SppS and LEAR). For later half of its working life operated in tandem with Antiproton Collector (AC), to form the Antiproton Accumulation Complex (AAC).[100]

- The Antiproton Collector (AC),[101][102] built 1986–1987, operations ended in 1997 and the machine was converted into the Antiproton Decelerator (AD), which is the successor machine for Low Energy Antiproton Ring (LEAR). Operated in tandem with Antiproton Accumulator (AA) and the pair formed the Antiproton Accumulation Complex (AAC),[100] whose purpose was to store antiprotons produced by the Proton Synchrotron (PS) for use in other experiments and accelerators, like the Low Energy Antiproton Ring (LEAR) and Super Proton–Antiproton Synchrotron (SppS).

- The Compact Linear Collider Test Facility 3 (CTF3), which studied feasibility for the future normal conducting linear collider project (the CLIC collider). In operation 2001–2016.[98] One of its beamlines has been converted, from 2017 on, into the new CERN Linear Electron Accelerator for Research (CLEAR) facility.

Possible future accelerators

Sites

The smaller accelerators are on the main Meyrin site (also known as the West Area), which was originally built in Switzerland alongside the French border, but has been extended to span the border since 1965. The French side is under Swiss jurisdiction and there is no obvious border within the site, apart from a line of marker stones.

The SPS and LEP/LHC tunnels are almost entirely outside the main site, and are mostly buried under French farmland and invisible from the surface. However, they have surface sites at various points around them, either as the location of buildings associated with experiments or other facilities needed to operate the colliders such as cryogenic plants and access shafts. The experiments are located at the same underground level as the tunnels at these sites.

Three of these experimental sites are in France, with ATLAS in Switzerland, although some of the ancillary cryogenic and access sites are in Switzerland. The largest of the experimental sites is the Prévessin site, also known as the North Area, which is the target station for non-collider experiments on the SPS accelerator. Other sites are the ones which were used for the UA1, UA2 and the LEP experiments (the latter are used by LHC experiments).

Outside of the LEP and LHC experiments, most are officially named and numbered after the site where they were located. For example, NA32 was an experiment looking at the production of so-called "charmed" particles and located at the Prévessin (North Area) site while WA22 used the Big European Bubble Chamber (BEBC) at the Meyrin (West Area) site to examine neutrino interactions. The UA1 and UA2 experiments were considered to be in the Underground Area, i.e. situated underground at sites on the SPS accelerator.

Most of the roads on the CERN Meyrin and Prévessin sites are named after famous physicists, such as Wolfgang Pauli, who pushed for CERN's creation. Other notable names are Richard Feynman, Albert Einstein, and Bohr.

Participation and funding

Member states and budget

Since its foundation by 12 members in 1954, CERN regularly accepted new members. All new members have remained in the organization continuously since their accession, except Spain and Yugoslavia. Spain first joined CERN in 1961, withdrew in 1969, and rejoined in 1983. Yugoslavia was a founding member of CERN but quit in 1961. Of the 23 members, Israel joined CERN as a full member on 6 January 2014,[103] becoming the first (and currently only) non-European full member.[104]

The budget contributions of member states are computed based on their GDP.[105]

| Member state | Status since | Contribution (million CHF for 2019) |

Contribution (fraction of total for 2019) |

Contribution per capita[note 1] (CHF/person for 2017) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Founding Members[note 2] | ||||

| 29 September 1954 | 30.7 | 2.68% | 2.7 | |

| 29 September 1954 | 20.5 | 1.79% | 3.4 | |

| 29 September 1954 | 160.3 | 14.0% | 2.6 | |

| 29 September 1954 | 236.0 | 20.6% | 2.8 | |

| 29 September 1954 | 12.5 | 1.09% | 1.6 | |

| 29 September 1954 | 118.4 | 10.4% | 2.1 | |

| 29 September 1954 | 51.8 | 4.53% | 3.0 | |

| 29 September 1954 | 28.3 | 2.48% | 5.4 | |

| 29 September 1954 | 30.5 | 2.66% | 3.0 | |

| 29 September 1954 | 47.1 | 4.12% | 4.9 | |

| 29 September 1954 | 184.0 | 16.1% | 2.4 | |

| 29 September 1954[108][109] | 0 | 0% | 0.0 | |

| Acceded Members[note 4] | ||||

| 1 June 1959 | 24.7 | 2.16% | 2.9 | |

| 1 January 1983[109][111] | 80.7 | 7.06% | 2.0 | |

| 1 January 1986 | 12.5 | 1.09% | 1.3 | |

| 1 January 1991 | 15.1 | 1.32% | 2.8 | |

| 1 July 1991 | 31.9 | 2.79% | 0.8 | |

| 1 July 1992 | 7.0 | 0.609% | 0.7 | |

| 1 July 1993 | 10.9 | 0.950% | 1.1 | |

| 1 July 1993 | 5.6 | 0.490% | 1.0 | |

| 11 June 1999 | 3.4 | 0.297% | 0.4 | |

| 6 January 2014[103] | 19.7 | 1.73% | 2.7 | |

| 17 July 2016[112] | 12.0 | 1.05% | 0.6 | |

| 24 March 2019[113] | 2.5 | 0.221% | 0.1 | |

| Associate Members in the pre-stage to membership | ||||

| 1 April 2016[114] | 1.0 | N/A | N/A | |

| 4 July 2017[115][116] | 1.0 | N/A | N/A | |

| 1 February 2021[117][118] | 1.0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Associate Members | ||||

| 6 May 2015[119] | 5.7 | N/A | N/A | |

| 31 July 2015[120] | 1.7 | N/A | N/A | |

| 5 October 2016[121] | 1.0 | N/A | N/A | |

| 16 January 2017[122] | 13.8 | N/A | N/A | |

| 8 January 2018[123] | 1.0 | N/A | N/A | |

| 10 October 2019[124] | 0.25 | N/A | N/A | |

| 2 August 2021[125] | N/A | N/A | ||

| Total Members, Candidates and Associates | 1,171.2[105][126] | 100.0% | N/A | |

- ↑ Based on the population in 2017.

- ↑ 12 founding members drafted the Convention for the Establishment of a European Organization for Nuclear Research which entered into force on 29 September 1954.[106][107]

- ↑ Yugoslavia left the organization in 1961.

- ↑ Acceded members become CERN member states by ratifying the CERN convention.[110]

- ↑ Spain was previously a member state from 1961 to 1969

| Maps of the history of CERN membership |

|---|

|

Enlargement

Associate Members, Candidates:

- Turkey signed an association agreement on 12 May 2014[127] and became an associate member on 6 May 2015.

- Pakistan signed an association agreement on 19 December 2014[128] and became an associate member on 31 July 2015.[129][130]

- Cyprus signed an association agreement on 5 October 2012 and became an associate member in the pre-stage to membership on 1 April 2016.[114]

- Ukraine signed an association agreement on 3 October 2013. The agreement was ratified on 5 October 2016.[121]

- India signed an association agreement on 21 November 2016.[131] The agreement was ratified on 16 January 2017.[122]

- Slovenia was approved for admission as an Associate Member state in the pre-stage to membership on 16 December 2016.[115] The agreement was ratified on 4 July 2017.[116]

- Lithuania was approved for admission as an Associate Member state on 16 June 2017. The association agreement was signed on 27 June 2017 and ratified on 8 January 2018.[132][123]

- Croatia was approved for admission as an Associate Member state on 28 February 2019. The agreement was ratified on 10 October 2019.[124]

- Estonia was approved for admission as an Associate Member in the pre-stage to membership state on 19 June 2020. The agreement was ratified on 1 February 2021.[117]

- Latvia and CERN signed an associate membership agreement on 14 April 2021.[133] Latvia was formally admitted as an Associate Member on 2 August 2021.[125]

International relations

Three countries have observer status:[134]

- Japan – since 1995

- Russia – since 1993 (suspended as of March 2022)[135]

- United States – since 1997

Also observers are the following international organizations:

- UNESCO – since 1954

- European Commission – since 1985

- JINR – since 2014 (suspended as of March 2022)[136]

Non-Member States (with dates of Co-operation Agreements) currently involved in CERN programmes are:[137][138]

- Albania – October 2014

- Algeria – 2008

- Argentina – 11 March 1992

- Armenia – 25 March 1994

- Australia – 1 November 1991

- Azerbaijan – 3 December 1997

- Bangladesh – 2014

- Belarus – 28 June 1994 (suspended as of March 2022[136])

- Bolivia – 2007

- Bosnia & Herzegovina – 16 February 2021[139]

- Brazil – 19 February 1990 & October 2006

- Canada – 11 October 1996

- Chile – 10 October 1991

- China – 12 July 1991, 14 August 1997 & 17 February 2004

- Colombia – 15 May 1993

- Costa Rica – February 2014

- Ecuador – 1999

- Egypt – 16 January 2006

- Georgia – 11 October 1996

- Iceland – 11 September 1996

- Iran – 5 July 2001

- Jordan – 12 June 2003[140] MoU with Jordan and SESAME, in preparation of a cooperation agreement signed in 2004.[141]

- Kazakhstan – June 2018

- Lebanon – 2015

- Malta – 10 January 2008[142][143]

- Mexico – 20 February 1998

- Mongolia – 2014

- Montenegro – 12 October 1990

- Morocco – 14 April 1997

- Nepal – 19 September 2017

- New Zealand – 4 December 2003

- North Macedonia – 27 April 2009

- Palestine – December 2015

- Paraguay – January 2019

- Peru – 23 February 1993

- Philippines – 2018

- Qatar – 2016

- Republic of Korea (South Korea) – 25 October 2006

- Saudi Arabia – 2006

- South Africa – 4 July 1992

- Sri Lanka – February 2017

- Thailand – 2018

- Tunisia – May 2014

- United Arab Emirates – 2006

- Vietnam – 2008

CERN also has scientific contacts with the following other countries:[137][144]

- Bahrain

- Cuba

- Ghana

- Honduras

- Hong Kong

- Indonesia

- Ireland

- Kuwait

- Luxemburg

- Madagascar

- Malaysia

- Mauritius

- Morocco

- Mozambique

- Oman

- Rwanda

- Singapore

- Sudan

- Taiwan

- Tanzania

- Uzbekistan

- Zambia

International research institutions, such as CERN, can aid in science diplomacy.[145]

Associated institutions

- European Molecular Biology Laboratory, organization based on the CERN model[147]

- European Space Research Organisation (since 1975 ESA), organization based on the CERN model[148]

- European Southern Observatory, organization based on the CERN model[149]

- JINR, observer to CERN Council,[150] CERN is represented in the JINR Council.[151] JINR is currently suspended, due to the CERN Council Resolution of 25 March 2022.[137]

- SESAME, CERN is an observer to the SESAME Council[152]

- UNESCO, observer to CERN Council[153]

.cern

Template:Infobox Top level domain

.cern is a top-level domain for CERN.[154][155] It was registered on 13 August 2014.[156][157] On 20 October 2015 CERN moved its main Website to https://home.cern.[158][159]

Open science

The Open Science movement focuses on making scientific research openly accessible and on creating knowledge through open tools and processes. Open access, open data, open source software and hardware, open licenses, digital preservation and reproducible research are primary components of open science and areas in which CERN has been working towards since its formation.

CERN has developed a number of policies and official documents that enable and promote open science, starting with CERN's founding convention in 1953 which indicated that all its results are to be published or made generally available.[14] Since then, CERN published its open access policy in 2014,[160] which ensures that all publications by CERN authors will be published with gold open access and most recently an open data policy that was endorsed by the four main LHC collaborations (ALICE, ATLAS, CMS and LHCb).[161] The open data policy complements the open access policy, addressing the public release of scientific data collected by LHC experiments after a suitable embargo period. Prior to this open data policy, guidelines for data preservation, access and reuse were implemented by each collaboration individually through their own policies which are updated when necessary.[162][163][164][165] The European Strategy for Particle Physics, a document mandated by the CERN Council that forms the cornerstone of Europe's decision-making for the future of particle physics, was last updated in 2020 and affirmed the organisation's role within the open science landscape by stating: “The particle physics community should work with the relevant authorities to help shape the emerging consensus on open science to be adopted for publicly-funded research, and should then implement a policy of open science for the field”.[166]

Beyond the policy level, CERN has established a variety of services and tools to enable and guide open science at CERN, and in particle physics more generally. On the publishing side, CERN has initiated and operates a global cooperative project, the Sponsoring Consortium for Open Access Publishing in Particle Physics, SCOAP3, to convert scientific articles in high-energy physics to open access. Currently, the SCOAP3 partnership represents 3000+ libraries from 44 countries and 3 intergovernmental organizations who have worked collectively to convert research articles in high-energy physics across 11 leading journals in the discipline to open access.[167][168]

Public-facing results can be served by various CERN-based services depending on their use case: the CERN Open Data portal,[169] Zenodo, the CERN Document Server,[170] INSPIRE and HEPData[171] are the core services used by the researchers and community at CERN, as well as the wider high-energy physics community for the publication of their documents, data, software, multimedia, etc. CERN's efforts towards preservation and reproducible research are best represented by a suite of services addressing the entire physics analysis lifecycle (such as data, software and computing environment). CERN Analysis Preservation[172] helps researchers to preserve and document the various components of their physics analyses; REANA (Reusable Analyses)[173] enables the instantiating of preserved research data analyses on the cloud.

All of the abovementioned services are built using open source software and strive towards compliance with best effort principles where appropriate and where possible, such as the FAIR principles, the FORCE11 guidelines and Plan S, while at the same time taking into account relevant activities carried out by the European Commission.[174]

Public exhibits

The Globe of Science and Innovation, which opened in late 2005, is open to the public. It is used four times a week for special exhibits.

The Microcosm museum previously hosted another on-site exhibition on particle physics and CERN history. It closed permanently on 18 September 2022, in preparation for the installation of the exhibitions in Science Gateway.[175]

CERN also provides daily tours to certain facilities such as the Synchro-cyclotron (CERNs first particle accelerator) and the superconducting magnet workshop.

In 2004, a two-meter statue of the Nataraja, the dancing form of the Hindu god Shiva, was unveiled at CERN. The statue, symbolizing Shiva's cosmic dance of creation and destruction, was presented by the Indian government to celebrate the research center's long association with India.[176] A special plaque next to the statue explains the metaphor of Shiva's cosmic dance with quotations from physicist Fritjof Capra:

Hundreds of years ago, Indian artists created visual images of dancing Shivas in a beautiful series of bronzes. In our time, physicists have used the most advanced technology to portray the patterns of the cosmic dance. The metaphor of the cosmic dance thus unifies ancient mythology, religious art and modern physics.[177]

Arts at CERN

CERN launched its Cultural Policy for engaging with the arts in 2011.[178][179] The initiative provided the essential framework and foundations for establishing Arts at CERN, the arts programme of the Laboratory.

Since 2012, Arts at CERN has fostered creative dialogue between art and physics through residencies, art commissions, exhibitions and events. Artists across all creative disciplines have been invited to CERN to experience how fundamental science pursues the big questions about our universe.

Even before the arts programme officially started, several highly regarded artists visited the Laboratory, drawn to physics and fundamental science. As early as 1972, James Lee Byars was the first artist to visit the Laboratory and the only one, so far, to feature on the cover of the CERN Courier.[180] Mariko Mori,[181] Gianni Motti,[182] Cerith Wyn Evans,[183] John Berger[184] and Anselm Kiefer[185] are among the artists who came to CERN in the years that followed.

The programmes of Arts at CERN are structured according to their values and vision to create bridges between cultures. Each programme is designed and formed in collaboration with cultural institutions, other partner laboratories, countries, cities and artistic communities eager to connect with CERN's research, support their activities, and contribute to a global network of art and science.

They comprise research-led artistic residencies that take place on-site or remotely. More than 200 artists from 80 countries have participated in the residencies to expand their creative practices at the Laboratory, benefiting from the involvement of 400 physicists, engineers and CERN staff. Between 500 and 800 applications are received every year. The programmes comprise Collide, the international residency programme organised in partnership with a city; Connect, a programme of residencies to foster experimentation in art and science at CERN and in scientific organisations worldwide in collaboration with Pro Helvetia, and Guest Artists, a short stay for artists to stay to engage with CERN's research and community.[186][187]

In popular culture

- The band Les Horribles Cernettes was founded by women from CERN. The name was chosen so to have the same initials as the LHC.[188][189]

- The science journalist Katherine McAlpine made a rap video called "Large Hadron Rap" about CERN's Large Hadron Collider with some of the facility's staff.[190][191]

- Particle Fever, a 2013 documentary, explores CERN throughout the inside and depicts the events surrounding the 2012 discovery of the Higgs Boson.

- John Titor, a self-proclaimed time traveler, alleged that CERN would invent time travel in 2001.

- CERN is depicted in the visual novel/anime series Steins;Gate as SERN, a shadowy organization that has been researching time travel in order to restructure and control the world.

- In Robert J. Sawyer's 1999 science fiction novel Flashforward, as CERN's Large Hadron Collider accelerator is performing a run to search for the Higgs boson the entire human race sees themselves twenty-one years and six months in the future.

- A number of conspiracy theories feature CERN, accusing the organization of partaking in occult rituals and secret experiments involving opening portals into Hell or other dimensions, shifting the world into an alternative timeline and causing earthquakes.[192][193]

- In Dan Brown's 2000 mystery-thriller novel Angels & Demons and 2009 film of the same name, a canister of antimatter is stolen from CERN.[194]

- CERN is depicted in a 2009 episode of South Park (Season 13, Episode 6), "Pinewood Derby". Randy Marsh, the father of one of the main characters, breaks into the "Hadron Particle Super Collider in Switzerland" and steals a "superconducting bending magnet created for use in tests with particle acceleration" to use in his son Stan's Pinewood Derby racer.[195]

- In the 2010 season 3 episode 15 of the TV situation comedy The Big Bang Theory, "The Large Hadron Collision", Leonard and Raj travel to CERN to attend a conference and see the LHC.

- The 2012 student film Decay, which centers on the idea of the Large Hadron Collider transforming people into zombies, was filmed on location in CERN's maintenance tunnels.[196]

- The Compact Muon Solenoid at CERN was used as the basis for the Megadeth's Super Collider album cover.

- CERN forms part of the back story of the massively multiplayer augmented reality game Ingress,[197] and in the 2018 Japanese anime television series Ingress: The Animation, based on Niantic's augmented reality mobile game of the same name.

- In 2015, Sarah Charley, US communications manager for LHC experiments at CERN with graduate students Jesse Heilman of the University of California, Riverside, and Tom Perry and Laser Seymour Kaplan of the University of Wisconsin, Madison created a parody video based on "Collide", a song by American artist Howie Day.[198] The lyrics were changed to be from the perspective of a proton in the Large Hadron Collider. After seeing the parody, Day re-recorded the song with the new lyrics, and released a new version of "Collide" in February 2017 with a video created during his visit to CERN.[199]

- In 2015, Ryoji Ikeda created an art installation called "Supersymmetry" based on his experience as a resident artist at CERN.[200]

- The television series Mr. Robot features a secretive, underground project apparatus that resembles the ATLAS experiment.

- Parallels, a Disney+ television series released in March 2022, includes a particle-physics laboratory at the French-Swiss border called "ERN". Various accelerators and facilities at CERN are referenced during the show, including ATLAS, CMS, the Antiproton Decelerator, and the FCC.[201][202][203]

See also

- CERN Openlab

- Fermilab

- Joint Institute for Nuclear Research

- Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek

- Science and Technology Facilities Council

- Science and technology in Switzerland

- Science diplomacy

- Scientific Linux

- SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

- World Wide Web

References

- ↑ James Gillies (2018). CERN and the Higgs Boson: The Global Quest for the Building Blocks of Reality. Icon Books Ltd.. ISBN 978-1-78578-393-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=0etmDwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ "Prof. Eliezer Rabinovici is the new president of the CERN Council". 25 September 2021. https://www.jpost.com/international/prof-eliezer-rabinovici-is-the-new-president-of-the-cern-council-680229.

- ↑ "Final Budget of the Organization for the sixty-eighth financial year 2022". https://cds.cern.ch/record/2799091/files/English.pdf.

- ↑ CERN (2020). "Governance" (in en). CERN Annual Report (CERN) 2019: 50. doi:10.17181/ANNUALREPORT2019. https://cds.cern.ch/record/2723123.

- ↑ "CERN to admit Israel as first new member state since 1999 – CERN Courier". 22 January 2014. https://cerncourier.com/cws/article/cern/55869.

- ↑ "CERN accepts Israel as full member" (in en-US). 12 December 2013. http://www.timesofisrael.com/cern-accepts-israel-as-full-member/.

- ↑ "Intergovernmental Organizations". United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/about-us/intergovernmental-and-other-organizations.

- ↑ CERN (2020). "CERN in figures" (in en). CERN Annual Report (CERN) 2019: 53. doi:10.17181/ANNUALREPORT2019. https://cds.cern.ch/record/2723123.

- ↑ "Discovery machines" (in en). CERN Annual report 2016. Annual Report of the European Organization for Nuclear Research. 2016. CERN. 2017. pp. 20–29. https://cds.cern.ch/record/2270811?ln=en.

- ↑ "The Large Hadron Collider" (in en). https://home.cern/science/accelerators/large-hadron-collider.

- ↑ McPherson, Stephanie Sammartino (2009). Tim Berners-Lee: Inventor of the World Wide Web. Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 978-0-8225-7273-2. https://archive.org/details/timbernerslee0000mcph.

- ↑ Gillies, James; Cailliau, Robert (2000) (in en). How the Web was Born: The Story of the World Wide Web. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-286207-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=pIH-JijUNS0C&q=How+the+Web+Was+Born+%3A+The+Story+of+the+World+Wide+Web.

- ↑ "CERN.ch". CERN. https://public.web.cern.ch/public/en/About/History54-en.html.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Convention for the Establishment of a European Organization for Nuclear Research | CERN Council". Article II. https://council.web.cern.ch/en/convention.

- ↑ Hermann, Armin; Belloni, Lanfranco; Krige, John (1987). History of CERN. European Organization for Nuclear Research. Amsterdam: North-Holland Physics Pub. ISBN 0-444-87037-7. OCLC 14692480. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/14692480.

- ↑ Krige, John (1985) (in en). From the Provisional Organization to the Permanent CERN, May 1952 – September 1954: A survey of developments. Study Team for CERN History. pp. 5. https://books.google.com/books?id=yzE9AQAAIAAJ&q=oern.

- ↑ Dakin, S. A. ff. (2 November 1954). "Conflict between title and initials of the Organization". https://cds.cern.ch/record/59712/files/Memo%202%20November%201954%20.pdf.

- ↑ Fraser, Gordon (2012) (in en). The Quantum Exodus: Jewish Fugitives, the Atomic Bomb, and the Holocaust. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-162751-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=xwGhmwYyDLQC&q=%22OERN%22+heisenberg&pg=PA229.

- ↑ "Lew Kowarski – Session VI" (in en). 2015-03-20. https://www.aip.org/history-programs/niels-bohr-library/oral-histories/4717-6.

- ↑ "People and things: Felix Bloch". CERN Courier. 1983. https://cds.cern.ch/record/1730968. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ↑ 6th Session of the European Council for Nuclear Research, 29–30 Jun 1953: Minutes. Paris: CERN. 28 September 2023. https://cds.cern.ch/record/17750/.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Cashmore, Roger, ed (2003) (in en). Prestigious discoveries at CERN. Berlin & Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-12779-7. ISBN 978-3-642-05855-4. https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-662-12779-7.

- ↑ Mele, Salvatore (2015), "The measurement of the number of light neutrino species at LEP" (in en), 60 Years of CERN Experiments and Discoveries, Advanced Series on Directions in High Energy Physics, 23, World Scientific, pp. 89–106, doi:10.1142/9789814644150_0004, ISBN 978-981-4644-14-3, https://www.worldscientific.com/doi/abs/10.1142/9789814644150_0004, retrieved 2021-02-23

- ↑ Close, Frank (2018) (in en). Antimatter. Oxford University Press. pp. 93–96. ISBN 978-0-19-883191-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=lLRwDwAAQBAJ&q=first++1995+antihydrogen&pg=PA93.

- ↑ Baur, G.; Boero, G.; Brauksiepe, A.; Buzzo, A.; Eyrich, W.; Geyer, R.; Grzonka, D.; Hauffe, J. et al. (1996). "Production of antihydrogen" (in en). Physics Letters B 368 (3): 251–258. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(96)00005-6. Bibcode: 1996PhLB..368..251B. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0370269396000056.

- ↑ The ALEPH Collaboration; The DELPHI Collaboration; The L3 Collaboration; The OPAL Collaboration; The SLD Collaboration; The LEP Electroweak Working Group; The SLD Electroweak Group; The SLD Heavy Flavour Group (May 2006). "Precision electroweak measurements on the Z resonance". Physics Reports 427 (5–6): 257–454. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2005.12.006. Bibcode: 2006PhR...427..257A. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0370157305005119. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ↑ Blondel, Alain; Mariotti, Chiara; Pieri, Marco; Wells, Pippa (11 September 2019). "LEP's electroweak leap". CERN Courier. https://cerncourier.com/a/leps-electroweak-leap/.

- ↑ Fanti, V. et al. (1999). "A new measurement of direct CP violation in two pion decays of the neutral kaon". Physics Letters B 465 (1–4): 335–348. doi:10.1016/S0370-2693(99)01030-8. Bibcode: 1999PhLB..465..335F. https://na48.web.cern.ch/NA48/Welcome/papers/eprime97/eprime97.pdf.

- ↑ "New State of Matter created at CERN" (in en). https://home.cern/news/press-release/cern/new-state-matter-created-cern.

- ↑ Reich, Eugenie Samuel (2010). "Antimatter held for questioning" (in en). Nature 468 (7322): 355. doi:10.1038/468355a. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 21085144. Bibcode: 2010Natur.468..355R.

- ↑ Shaikh, Thair (18 November 2010). "Scientists capture antimatter atoms in particle breakthrough". CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2010/WORLD/europe/11/18/switzerland.cern.antimatter/?hpt=Mid.

- ↑ Matson, John (2011). "Antimatter trapped for more than 15 minutes" (in en). Nature: news.2011.349. doi:10.1038/news.2011.349. ISSN 0028-0836. https://www.nature.com/articles/news.2011.349.

- ↑ Amos, Jonathan (6 June 2011). "Antimatter atoms are corralled even longer". BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-13666892.

- ↑ Randall, Lisa (2012) (in en). Higgs Discovery: The Power of Empty Space. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4481-6116-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=qcL1D2vlMKoC.

- ↑ Aad, G.; Abajyan, T.; Abbott, B.; Abdallah, J.; Abdel Khalek, S.; Abdelalim, A.A.; Abdinov, O.; Aben, R. et al. (2012). "Observation of a new particle in the search for the Standard Model Higgs boson with the ATLAS detector at the LHC" (in en). Physics Letters B 716 (1): 1–29. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2012.08.020. Bibcode: 2012PhLB..716....1A. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S037026931200857X.

- ↑ Chatrchyan, S. et al. (2012). "Observation of a new boson at a mass of 125 GeV with the CMS experiment at the LHC" (in en). Physics Letters B 716 (1): 30–61. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2012.08.021. ISSN 0370-2693. Bibcode: 2012PhLB..716...30C. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0370269312008581.

- ↑ Adrian Cho, "Neutrinos Travel Faster Than Light, According to One Experiment", Science NOW, 22 September 2011.

- ↑ "OPERA experiment reports anomaly in flight time of neutrinos from CERN to Gran Sasso". CERN. https://press.cern/press-releases/2011/09/opera-experiment-reports-anomaly-flight-time-neutrinos-cern-gran-sasso.

- ↑ Sutton, Christine (1984-10-25). "CERN scoops up the Nobel physics prize" (in en). New Scientist (Reed Business Information). https://books.google.com/books?id=mba_9vGmyesC&q=nobel+prize+rubbia+meer&pg=PA10.

- ↑ Segal, Ben (1995). "A short history of Internet protocols at CERN". CERN. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/245061001.

- ↑ O’Regan, Gerard (2013) (in en). Giants of Computing: A Compendium of Select, Pivotal Pioneers. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4471-5340-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=oSq5BAAAQBAJ.

- ↑ O’Regan, Gerard (2018) (in en). The Innovation in Computing Companion: A Compendium of Select, Pivotal Inventions. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-02619-6. ISBN 978-3-030-02618-9. https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-02619-6.

- ↑ Scott, Virginia A. (2008) (in en). Google. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-35127-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=UVz06fnwJvUC&q=ENQUIRE+cern+web&pg=PA19.

- ↑ "CERN.ch". CERN. https://public.web.cern.ch/Public/en/About/WebStory-en.html.

- ↑ "Robert Cailliau" (in en). https://awards.acm.org/award_winners/cailliau_5353144.

- ↑ "The World Wide Web project". W3C. https://www.w3.org/History/19921103-hypertext/hypertext/WWW/TheProject.html.

- ↑ Ari-Pekka, Hameri; Nordberg, Markus (1997). "From Experience: Linking Available Resources and Technologies to Create a Solution for Document Sharing The Early Years of the WWW". https://cds.cern.ch/record/371101/files/from%20experience_linking%20avalble%20resources.pdf.

- ↑ Andrew, Oram (2021). "Open, Simple, Generative: Why the Web is the Dominant Internet Application". https://www.lpi.org/blog/2021/08/17/open-simple-generative-why-web-dominant-internet-application/.

- ↑ "Engineering at CERN". https://home.cern/science/engineering.

- ↑ "CERN Scientific Committees | CERN Scientific Information Service (SIS)". https://scientific-info.cern/archives/history_CERN/Scientific_committees.

- ↑ "CERN Website – LINAC". CERN. https://linac2.home.cern.ch/linac2/default.htm.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Chanel, Michel (2004). "LEIR: the low energy ion ring at CERN" (in en). Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 532 (1–2): 137–143. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2004.06.040. Bibcode: 2004NIMPA.532..137C. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0168900204011994.

- ↑ Hübner, K. (2006). Fifty years of research at CERN, from past to future: The Accelerators. CERN. doi:10.5170/cern-2006-004.1. https://cds.cern.ch/record/1058082.

- ↑ "LHC Run 3: the final countdown". CERN Courier. 18 February 2022. https://cerncourier.com/a/lhc-run-3-the-final-countdown/.

- ↑ Hanke, K. (2013). "Past and present operation of the CERN PS Booster" (in en). International Journal of Modern Physics A 28 (13): 1330019. doi:10.1142/S0217751X13300196. ISSN 0217-751X. Bibcode: 2013IJMPA..2830019H. https://www.worldscientific.com/doi/abs/10.1142/S0217751X13300196.

- ↑ Plass, Günther (2012), Alvarez-Gaumé, Luis; Mangano, Michelangelo; Tsesmelis, Emmanuel, eds., "The CERN Proton Synchrotron: 50 Years of Reliable Operation and Continued Development" (in en), From the PS to the LHC – 50 Years of Nobel Memories in High-Energy Physics (Berlin & Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg): pp. 29–47, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-30844-4_2, ISBN 978-3-642-30843-7, Bibcode: 2012fpl..book...29P, https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-642-30844-4_2, retrieved 2021-02-28

- ↑ Hatton, V. (1991). "Operational history of the SPS collider 1981–1990". Conference Record of the 1991 IEEE Particle Accelerator Conference. San Francisco: IEEE. pp. 2952–2954. doi:10.1109/PAC.1991.165151. ISBN 978-0-7803-0135-1. Bibcode: 1991pac..conf.2952H. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/165151.

- ↑ Watkins, Peter; Watkins (1986) (in en). Story of the W and Z. CUP Archive. ISBN 978-0-521-31875-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=J808AAAAIAAJ.

- ↑ Brüning, Oliver; Myers, Stephen (2015) (in en). Challenges and Goals for Accelerators in the XXI Century. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-4436-40-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=28DACwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Borge, Maria J. G.; Jonson, Björn (2017). "ISOLDE past, present and future". Journal of Physics G: Nuclear and Particle Physics 44 (4): 044011. doi:10.1088/1361-6471/aa5f03. ISSN 0954-3899. Bibcode: 2017JPhG...44d4011B.

- ↑ Ajduk, Zygmunt; Wroblewski, Andrzej Kajetan (1997) (in en). Proceedings Of The 28th International Conference On High Energy Physics (In 2 Volumes). World Scientific. pp. 1749. ISBN 978-981-4547-10-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=Y5HsCgAAQBAJ&q=Antiproton+Decelerator&pg=PA1749.

- ↑ Bartmann, W.; Belochitskii, P.; Breuker, H.; Butin, F.; Carli, C.; Eriksson, T.; Maury, S.; Oelert, W. et al. (2014). "Past, present and future low energy antiproton facilities at CERN" (in en). International Journal of Modern Physics: Conference Series 30: 1460261. doi:10.1142/S2010194514602610. ISSN 2010-1945. Bibcode: 2014IJMPS..3060261B. https://www.worldscientific.com/doi/abs/10.1142/S2010194514602610.

- ↑ Adli, E.; Ahuja, A.; Apsimon, O.; Apsimon, R.; Bachmann, A.-M.; Barrientos, D.; Batsch, F.; Bauche, J. et al. (2018). "Acceleration of electrons in the plasma wakefield of a proton bunch" (in en). Nature 561 (7723): 363–367. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0485-4. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 30188496. Bibcode: 2018Natur.561..363A.

- ↑ Gschwendtner, E.; Adli, E.; Amorim, L.; Apsimon, R.; Assmann, R.; Bachmann, A.-M.; Batsch, F.; Bauche, J. et al. (2016). "AWAKE, The Advanced Proton Driven Plasma Wakefield Acceleration Experiment at CERN" (in en). Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 829: 76–82. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2016.02.026. Bibcode: 2016NIMPA.829...76G. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0168900216001881.

- ↑ Sjobak, Kyrre; Adli, Erik; Bergamaschi, Michele; Burger, Stephane; Corsini, Roberto; Curcio, Alessandro; Curt, Stephane; Döbert, Steffen et al. (2019). Boland Mark (Ed.), Tanaka Hitoshi (Ed.), Button David (Ed.), Dowd Rohan (Ed.), Schaa, Volker RW (Ed.), Tan Eugene (Ed.). "Status of the CLEAR Electron Beam User Facility at CERN" (in en). Proceedings of the 10th Int. Particle Accelerator Conf. IPAC2019: 4 pages, 0.190 MB. doi:10.18429/JACOW-IPAC2019-MOPTS054. https://jacow.org/ipac2019/doi/JACoW-IPAC2019-MOPTS054.html.

- ↑ Gamba, D.; Corsini, R.; Curt, S.; Doebert, S.; Farabolini, W.; Mcmonagle, G.; Skowronski, P.K.; Tecker, F. et al. (2018). "The CLEAR user facility at CERN" (in en). Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 909: 480–483. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2017.11.080. Bibcode: 2018NIMPA.909..480G.

- ↑ Binoth, T.; Buttar, C.; Clark, P. J.; Glover, E. W. N. (2012) (in en). LHC Physics. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4398-3770-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=sMZDMZKLLx0C.

- ↑ The CMS Collaboration; Chatrchyan, S.; Hmayakyan, G.; Khachatryan, V.; Sirunyan, A. M.; Adam, W.; Bauer, T.; Bergauer, T. et al. (2008). "The CMS experiment at the CERN LHC". Journal of Instrumentation 3 (8): S08004. doi:10.1088/1748-0221/3/08/S08004. ISSN 1748-0221. Bibcode: 2008JInst...3S8004C.

- ↑ The ATLAS Collaboration (2019) (in en). ATLAS: A 25-Year Insider Story of the LHC Experiment. Advanced Series on Directions in High Energy Physics. 30. World Scientific. doi:10.1142/11030. ISBN 978-981-327-179-1. https://www.worldscientific.com/worldscibooks/10.1142/11030.

- ↑ Belyaev, I.; Carboni, G.; Harnew, N.; Teubert, C. Matteuzzi F. (2021). "The history of LHCb". European Physical Journal H 46 (1): 3. doi:10.1140/epjh/s13129-021-00002-z. Bibcode: 2021EPJH...46....3B.

- ↑ "MoEDAL becomes the LHC's magnificent seventh" (in en-GB). 2010-05-05. https://cerncourier.com/a/moedal-becomes-the-lhcs-magnificent-seventh/.

- ↑ The TOTEM Collaboration; Anelli, G.; Antchev, G.; Aspell, P.; Avati, V.; Bagliesi, M. G.; Berardi, V.; Berretti, M. et al. (2008). "The TOTEM Experiment at the CERN Large Hadron Collider". Journal of Instrumentation 3 (8): S08007. doi:10.1088/1748-0221/3/08/S08007. ISSN 1748-0221. Bibcode: 2008JInst...3S8007T.

- ↑ The LHCf Collaboration; Adriani, O.; Bonechi, L.; Bongi, M.; Castellini, G.; D'Alessandro, R.; Faus, D. A.; Fukui, K. et al. (2008). "The LHCf detector at the CERN Large Hadron Collider". Journal of Instrumentation 3 (8): S08006. doi:10.1088/1748-0221/3/08/S08006. ISSN 1748-0221. Bibcode: 2008JInst...3S8006L.

- ↑ Feng, Jonathan L.; Galon, Iftah; Kling, Felix; Trojanowski, Sebastian (2018). "ForwArd Search ExpeRiment at the LHC" (in en). Physical Review D 97 (3): 035001. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.97.035001. ISSN 2470-0010. Bibcode: 2018PhRvD..97c5001F. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevD.97.035001.

- ↑ Fabjan, C.; Schukraft, J. (2011). "The story of ALICE: Building the dedicated heavy ion detector at LHC". arXiv:1101.1257 [physics.ins-det].

- ↑ Overbye, Dennis (2008-07-29). "Let the Proton Smashing Begin. (The Rap Is Already Written.)" (in en-US). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/29/science/29cernrap.html.

- ↑ "LHC First Beam". CERN. https://press.cern/past-events/lhc-first-beam.

- ↑ Cho, Adrian (13 July 2012). "Higgs Boson Makes Its Debut After Decades-Long Search". Science 337 (6091): 141–143. doi:10.1126/science.337.6091.141. PMID 22798574. Bibcode: 2012Sci...337..141C.

- ↑ "New results indicate that particle discovered at CERN is a Higgs boson". CERN. https://press.cern/press-releases/2013/03/new-results-indicate-particle-discovered-cern-higgs-boson.

- ↑ O'Luanaigh, Cian. "First successful beam at record energy of 6.5 TeV". CERN. https://home.cern/about/updates/2015/04/first-successful-beam-record-energy-65-tev.

- ↑ O'Luanaigh, Cian. "Proton beams are back in the LHC". CERN. https://home.cern/about/updates/2015/04/proton-beams-are-back-lhc.

- ↑ "LHC smashes targets for 2016 run". 1 November 2016. https://home.cern/about/opinion/2016/11/lhc-smashes-targets-2016-run-0.

- ↑ Schaeffer, Anaïs. "LS2 Report: Review of a rather unusual year" (in en). https://home.cern/news/news/accelerators/ls2-report-review-rather-unusual-year.

- ↑ Mangano, Michelangelo (2020-03-09). "LHC at 10: the physics legacy" (in en-GB). https://cerncourier.com/a/lhc-at-10-the-physics-legacy/.

- ↑ CERN Yellow Reports: Monographs (2020). "CERN Yellow Reports: Monographs, Vol. 10 (2020): High-Luminosity Large Hadron Collider (HL-LHC): Technical design report" (in en). CERN Yellow Reports: Monographs: 16MB. doi:10.23731/CYRM-2020-0010. https://e-publishing.cern.ch/index.php/CYRM/issue/view/127.

- ↑ CERN Yellow Reports: Monographs (2020-09-18). Vretenar, Maurizio. ed. "Linac4 design report" (in en). CERN Yellow Reports: Monographs 2020-006. doi:10.23731/CYRM-2020-006. https://e-publishing.cern.ch/index.php/CYRM/issue/view/121.

- ↑ Haseroth, H.; Hill, C. E.; Langbein, K.; Tanke, E.; Taylor, C.; Têtu, P.; Warner, D.; Weiss, M. (1992). History, developments and recent performance of the CERN linac 1. https://cds.cern.ch/record/242664.

- ↑ "The tale of a billion-trillion protons". 30 November 2018. https://cerncourier.com/a/the-tale-of-a-billion-trillion-protons/.

- ↑ Fidecaro, Giuseppe, ed. "SC 33 symposium at CERN: Thirty-three years of physics at the CERN synchro-cyclotron; Geneva (Switzerland); 22 Apr 1991". Physics Reports 225 (1–3): 1–191. https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/physics-reports/vol/225/issue/1.

- ↑ "The Synchrocyclotron prepares for visitors". 28 September 2023. https://home.cern/news/news/accelerators/synchrocyclotron-prepares-visitors.

- ↑ Hübner, Kurt (2012). "The CERN intersecting storage rings (ISR)" (in en). The European Physical Journal H 36 (4): 509–522. doi:10.1140/epjh/e2011-20058-8. ISSN 2102-6459. Bibcode: 2012EPJH...36..509H. https://link.springer.com/10.1140/epjh/e2011-20058-8.

- ↑ Myers, Stephen (2016), "The CERN Intersecting Storage Rings" (in en), Challenges and Goals for Accelerators in the XXI Century (World Scientific): pp. 135–151, doi:10.1142/9789814436403_0009, ISBN 978-981-4436-39-7, Bibcode: 2016cgat.book..135M, https://www.worldscientific.com/doi/abs/10.1142/9789814436403_0009, retrieved 2021-03-02

- ↑ Schmidt, Rudiger (2016), "The CERN SPS proton–antiproton collider" (in en), Challenges and Goals for Accelerators in the XXI Century (World Scientific): pp. 153–167, doi:10.1142/9789814436403_0010, ISBN 978-981-4436-39-7, Bibcode: 2016cgat.book..153S, https://www.worldscientific.com/doi/abs/10.1142/9789814436403_0010, retrieved 2021-03-02

- ↑ Schopper, Herwig (2009) (in en-gb). LEP – The Lord of the Collider Rings at CERN 1980-2000. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-89301-1. ISBN 978-3-540-89300-4. Bibcode: 2009llcr.book.....S. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007%2F978-3-540-89301-1.

- ↑ Picasso, Emilio (2012). "A few memories from the days at LEP" (in en). The European Physical Journal H 36 (4): 551–562. doi:10.1140/epjh/e2011-20050-0. ISSN 2102-6459. Bibcode: 2012EPJH...36..551P. https://link.springer.com/10.1140/epjh/e2011-20050-0.

- ↑ Battisti, S.; Bossart, R.; Delahaye, J. P.; Hubner, K.; Garoby, R.; Kugler, H.; Krusche, A.; Madsen, J. H. B. et al. (1989). "Accelerator Science and Technology". 1989 IEEE Particle Accelerator Conference. Chicago: IEEE. pp. 1815–1817. doi:10.1109/PAC.1989.72934. Bibcode: 1989pac..conf.1815B. http://cds.cern.ch/record/2844301.

- ↑ Battisti, S.; Bell, M.; Delahaye, J. P.; Krusche, A.; Kugler, H.; Madsen, J. H. B.; Poncet, Alain (1984). The design of the LEP electron positron accumulator (EPA). https://cds.cern.ch/record/165032/.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 Corsini, Roberto (2017). Schaa, Volker RW (Ed.), Arduini Gianluigi (Ed.), Pranke Juliana (Ed.), Seidel Mike (Ed.), Lindroos Mats (Ed.). "Final Results From the Clic Test Facility (CTF3)" (in en). Proceedings of the 8th International Particle Accelerator Conference IPAC2017: 6 pages, 0.817 MB. doi:10.18429/JACOW-IPAC2017-TUZB1. https://jacow.org/ipac2017/doi/JACoW-IPAC2017-TUZB1.html.

- ↑ Möhl, D. (1999). LEAR, history and early achievements. https://cds.cern.ch/record/388662.

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 Koziol, H.; Möhl, D. (2004). "The CERN antiproton collider programme: accelerators and accumulation rings" (in en). Physics Reports 403-404: 91–106. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2004.09.001. Bibcode: 2004PhR...403...91K. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0370157304003503.

- ↑ Autin, Bruno (1984). "The CERN antiproton collector" (in en). CERN Reports CERN-84-15: 525–541. doi:10.5170/CERN-1984-015.525. https://cds.cern.ch/record/156910.

- ↑ Wilson, Edmund J N (1983). "Design study of an antiproton collector for the antiproton accumulator (ACOL)" (in en). CERN Reports CERN-83-10. doi:10.5170/CERN-1983-010. https://cds.cern.ch/record/148148.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 "Israel". CERN. https://international-relations.web.cern.ch/International-Relations/ms/il.html.

- ↑ Rahman, Fazlur. (11 November 2013) Israel may become first non-European member of nuclear research group CERN – Diplomacy and Defense Israel News. Haaretz. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 "Member States' Contributions – 2019". CERN. https://fap-dep.web.cern.ch/rpc/member-states-contributions.

- ↑ ESA Convention (6th ed.). European Space Agency. September 2005. ISBN 978-92-9092-397-8. https://www.esa.int/esapub/sp/sp1300/sp1300EN1.pdf.

- ↑ "Convention for the Establishment of a European Organization for Nuclear Research". CERN. https://council.web.cern.ch/council/en/governance/Convention.html.

- ↑ "Member States". CERN. https://international-relations.web.cern.ch/international-relations/ms/.

- ↑ 109.0 109.1 "Member States". CERN. https://timeline.web.cern.ch/timelines/Member-states.

- ↑ "CERN Member States". CERN. https://council.web.cern.ch/council/en/MemberStates.html.

- ↑ "Spain". CERN. https://international-relations.web.cern.ch/International-Relations/ms/es.html.

- ↑ "CERN welcomes Romania as its twenty-second Member State | Media and Press Relations" (in en). https://press.cern/press-releases/2016/07/cern-welcomes-romania-its-twenty-second-member-state.

- ↑ "Serbia joins CERN as its 23rd Member State". CERN. 24 March 2019. https://home.cern/news/press-release/cern/serbia-joins-cern-its-23rd-member-state.

- ↑ 114.0 114.1 "Cyprus". CERN. https://international-relations.web.cern.ch/International-Relations/assoc/cyprus.html.

- ↑ 115.0 115.1 "Slovenia to enter the Associate Member State family of CERN". CERN. 16 December 2016. https://press.cern/press-releases/2016/12/slovenia-enter-associate-member-state-family-cern.

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 "Slovenia becomes an Associate Member in the pre-stage to Membership at CERN". CERN. 4 July 2017. https://press.cern/update/2017/07/slovenia-becomes-associate-member-pre-stage-membership-cern.

- ↑ 117.0 117.1 "Estonia becomes an Associate Member of CERN in the pre-stage to Membership" (in en). https://home.cern/news/news/cern/estonia-becomes-associate-member-cern-pre-stage-membership.

- ↑ "Estonia to become associate member of CERN" (in en). https://www.mkm.ee/en/news/estonia-become-associate-member-cern.

- ↑ "Turkey". CERN. https://international-relations.web.cern.ch/International-Relations/assoc/turkey.html.

- ↑ "Pakistan". CERN. https://international-relations.web.cern.ch/International-Relations/assoc/pakistan.html.

- ↑ 121.0 121.1 "Ukraine becomes an associate member of CERN". CERN. 5 October 2016. https://home.cern/news/news/cern/ukraine-becomes-associate-member-cern.

- ↑ 122.0 122.1 "India becomes Associate Member State of CERN". CERN. 16 January 2017. https://home.cern/about/updates/2017/01/india-becomes-associate-member-state-cern.

- ↑ 123.0 123.1 Jarlett, Harriet Kim (8 January 2018). "Lithuania becomes Associate Member State of CERN". https://home.cern/about/updates/2018/01/lithuania-becomes-associate-member-state-cern.

- ↑ 124.0 124.1 "Croatia | International Relations". https://international-relations.web.cern.ch/stakeholder-relations/states/croatia.

- ↑ 125.0 125.1 "Latvia becomes Associate Member State of CERN" (in en). CERN. 2 August 2021. https://home.cern/news/news/cern/latvia-becomes-associate-member-state-cern.

- ↑ "2021 Annual Contributions to CERN budget". https://fap-dep.web.cern.ch/rpc/2021-annual-contributions-cern-budget.

- ↑ "Turkey to become Associate Member State of CERN". CERN. 12 May 2014. https://home.cern/about/updates/2014/05/turkey-become-associate-member-state-cern.

- ↑ "Pakistan Becomes the First Associate CERN Member from Asia". Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Government of Pakistan. 20 June 2014. https://www.mofa.gov.pk/pr-details.php?prID=2050.

- ↑ "Pakistan becomes Associate Member State of CERN". https://home.cern/about/updates/2015/07/pakistan-becomes-associate-member-state-cern.

- ↑ "Pakistan officially becomes an associate member of CERN – The Express Tribune". 31 July 2015. https://tribune.com.pk/story/930265/pakistan-officially-becomes-an-associate-member-of-cern/.

- ↑ "India to become Associate Member State of CERN". 21 November 2016. https://press.cern/press-releases/2016/11/india-become-associate-member-state-cern.

- ↑ "Lithuania has become associate member of CERN". https://www.lrp.lt/en/press-centre/press-releases/lithuania-has-become-associate-member-of-cern/27822.

- ↑ "Latvia to join CERN as an Associate Member State" (in en). CERN. 14 April 2021. https://home.cern/news/press-release/cern/latvia-join-cern-associate-member-state.

- ↑ "Observers". CERN. https://international-relations.web.cern.ch/International-Relations/obs/.

- ↑ "CERN Council responds to Russian invasion of Ukraine". CERN. https://home.cern/news/news/cern/cern-council-responds-russian-invasion-ukraine.

- ↑ 136.0 136.1 "CERN Council takes further measures in response to the invasion of Ukraine". CERN. https://home.cern/news/news/cern/cern-council-takes-further-measures-response-invasion-ukraine.

- ↑ 137.0 137.1 137.2 "Member states". CERN. https://home.cern/about/member-states.

- ↑ "Associate & Non-Member State Relations | International Relations". https://international-relations.web.cern.ch/stakeholder-relations/Associate-Non-Member-State-Relations#NMS.

- ↑ "CERN lays foundations for collaboration with Bosnia and Herzegovina through International Cooperation Agreement". https://home.cern/news/news/cern/cern-lays-foundations-collaboration-bosnia-and-herzegovina-through-international.

- ↑ "Jordan". CERN. https://international-relations.web.cern.ch/international-relations/nms/jordan.html.

- ↑ "SESAME". CERN. 17 October 2011. https://international-relations.web.cern.ch/International-Relations/orgints/sesame.html.

- ↑ "Prime Minister of Malta visits CERN". CERN. 10 January 2008. https://cds.cern.ch/journal/CERNBulletin/2008/06/News%20Articles/1083445.

- ↑ "Malta signs agreement with CERN". The Times (Malta). 11 January 2008. https://www.timesofmalta.com/articles/view/20080111/local/malta-signs-agreement-with-cern.191318.

- ↑ "Associate & Non-Member State Relations | International Relations". https://international-relations.web.cern.ch/stakeholder-relations/Associate-Non-Member-State-Relations.

- ↑ Quevedo, Fernando (July 2013). "The Importance of International Research Institutions for Science Diplomacy". Science & Diplomacy 2 (3). https://www.sciencediplomacy.org/perspective/2013/importance-international-research-institutions-for-science-diplomacy.

- ↑ "ESO and CERN Sign Cooperation Agreement". https://www.eso.org/public/announcements/ann15098/.

- ↑ "EMBL History – EMBL". 2014-04-13. http://www.embl.de/aboutus/general_information/history/.

- ↑ Bonnet, Roger-M.; Manno, Vittorio (1994) (in en). International Cooperation in Space: The Example of the European Space Agency. Harvard University Press. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-0-674-45835-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=shvdfRZ6nZ8C&pg=58.

- ↑ Blaauw, Adriaan (1991) (in en). ESO's Early History: The European Southern Observatory from Concept to Reality. ESO. pp. 8. ISBN 978-3-923524-40-2. https://www.eso.org/public/products/books/book_0044/.

- ↑ "JINR | International Relations". https://international-relations.web.cern.ch/stakeholder-relations/states/jinr.

- ↑ "Governing and Advisory Bodies of JINR" (in en-US). http://www.jinr.ru/jinr_structure-en/realisators-en/.

- ↑ "Members and observers of SESAME | SESAME | Synchrotron-light for Experimental Science and Applications in the Middle East". https://www.sesame.org.jo/about-us/members-sesame.

- ↑ "UNESCO | International Relations". https://international-relations.web.cern.ch/stakeholder-relations/states/unesco.

- ↑ ".cern – ICANNWiki". https://icannwiki.org/.cern.

- ↑ "About .cern". https://nic.cern/.

- ↑ ".cern Domain Delegation Data". Internet Assigned Numbers Authority. https://www.iana.org/domains/root/db/cern.html. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- ↑ ".cern registration policy". CERN. https://nic.cern/registration-policy/. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- ↑ Alvarez, E.; de Molina, M. Malo; Salwerowicz, M.; De Sousa, B. Silva; Smith, T.; Wagner, A. (2017). "First experience with the new .cern Top Level Domain". Journal of Physics: Conference Series 898 (10): 102012. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/898/10/102012. ISSN 1742-6588. Bibcode: 2017JPhCS.898j2012A.

- ↑ "Birthplace of the World Wide Web CERN Launches home.cern" (in en). https://www.circleid.com/posts/20160111_birthplace_of_the_world_wide_web_cern_launches_homecern/.

- ↑ Open Access Policy for CERN Publications (Report). Geneva: CERN. 2021. https://cds.cern.ch/record/1955574.

- ↑ CERN. Geneva (2020). CERN. Geneva. ed. CERN Open Data Policy for the LHC Experiments. doi:10.17181/CERN.QXNK.8L2G. https://cds.cern.ch/record/2745133.

- ↑ ALICE Collaboration (2014), ALICE data preservation strategy, CERN Open Data Portal, doi:10.7483/opendata.alice.54ne.x2ea, https://opendata.cern.ch/record/412, retrieved 2021-02-08

- ↑ ATLAS Collaboration (2014), ATLAS Data Access Policy, CERN Open Data Portal, doi:10.7483/opendata.atlas.t9yr.y7mz, https://opendata.cern.ch/record/413, retrieved 2021-02-08

- ↑ CMS Collaboration (2014), CMS data preservation, re-use and open access policy, CERN Open Data Portal, doi:10.7483/opendata.cms.udbf.jkr9, https://opendata.cern.ch/record/411, retrieved 2021-02-08

- ↑ LHCb Collaboration (2014), LHCb External Data Access Policy, Peter Clarke, CERN Open Data Portal, doi:10.7483/opendata.lhcb.hkjw.twsz, https://opendata.cern.ch/record/410, retrieved 2021-02-08

- ↑ European Strategy Group (2020) (in en). 2020 Update of the European Strategy for Particle Physics. CERN Council. doi:10.17181/ESU2020. ISBN 9789290835752. https://cds.cern.ch/record/2720129.

- ↑ Loizides, F.; Smidt, B. (2016). Positioning and Power in Academic Publishing: Players, Agents and Agendas: Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Electronic Publishing. IOS Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-61499-649-1. https://ebooks.iospress.nl/book/positioning-and-power-in-academic-publishing-players-agents-and-agendas-proceedings-of-the-20th-international-conference-on-electronic-publishing.

- ↑ Alexander Kohls; Salvatore Mele (2018-04-09). "Converting the Literature of a Scientific Field to Open Access through Global Collaboration: The Experience of SCOAP3 in Particle Physics" (in en). Publications 6 (2): 15. doi:10.3390/publications6020015. ISSN 2304-6775.

- ↑ Cowton, J; Dallmeier-Tiessen, S; Fokianos, P; Rueda, L; Herterich, P; Kunčar, J; Šimko, T; Smith, T (2015-12-23). "Open Data and Data Analysis Preservation Services for LHC Experiments". Journal of Physics: Conference Series 664 (3): 032030. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/664/3/032030. ISSN 1742-6588. Bibcode: 2015JPhCS.664c2030C.

- ↑ Vesely, Martin; Baron, Thomas; Le Meur, Jean-Yves; Simko, Tibor (2004). "CERN document server: Document management system for grey literature in a networked environment" (in en). Publishing Research Quarterly 20 (1): 77–83. doi:10.1007/BF02910863. ISSN 1053-8801. https://link.springer.com/10.1007/BF02910863.

- ↑ Maguire, Eamonn; Heinrich, Lukas; Watt, Graeme (2017). "HEPData: a repository for high energy physics data". Journal of Physics: Conference Series 898 (10): 102006. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/898/10/102006. ISSN 1742-6588. Bibcode: 2017JPhCS.898j2006M. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1742-6596/898/10/102006.

- ↑ Fokianos, Pamfilos; Feger, Sebastian; Koutsakis, Ilias; Lavasa, Artemis; Maciulaitis, Rokas; Naim, Kamran; Okraska, Jan; Papadopoulos, Antonios et al. (2020). Doglioni, C.; Kim, D.; Stewart, G.A. et al.. eds. "CERN Analysis Preservation and Reuse Framework: FAIR research data services for LHC experiments". EPJ Web of Conferences 245: 06011. doi:10.1051/epjconf/202024506011. ISSN 2100-014X. Bibcode: 2020EPJWC.24506011F.

- ↑ Šimko, Tibor; Heinrich, Lukas; Hirvonsalo, Harri; Kousidis, Dinos; Rodríguez, Diego (2019). Forti, A.; Betev, L.; Litmaath, M. et al.. eds. "REANA: A System for Reusable Research Data Analyses". EPJ Web of Conferences 214: 06034. doi:10.1051/epjconf/201921406034. ISSN 2100-014X. Bibcode: 2019EPJWC.21406034S.

- ↑ "Open Science" (in en). https://ec.europa.eu/info/research-and-innovation/strategy/goals-research-and-innovation-policy/open-science_en.

- ↑ "Microcosm to close permanently on 18 September" (in en). https://home.cern/news/announcement/cern/microcosm-close-permanently-18-september.

- ↑ "Faces and Places (page 3)". http://cerncourier.com/cws/article/cern/29122/3.

- ↑ "Shiva's Cosmic Dance at CERN | Fritjof Capra". http://www.fritjofcapra.net/shivas-cosmic-dance-at-cern/.

- ↑ "CERN launches Cultural Policy" (in en). https://home.cern/news/press-release/cern/cern-launches-cultural-policy.

- ↑ Røstvik, Camilla (2016) (in English). At the Edge of their Universe: Artists, Scientists and Outsiders at CERN. Manchester: The University of Manchester. pp. 168–188. https://research.manchester.ac.uk/en/studentTheses/at-the-edge-of-their-universe-artists-scientists-and-outsiders-at.

- ↑ "Front cover: One of the visitors, James Lee Byars, who brought some colour into the CERN corridors during the summer.". CERN Courier 12 (9). 1972. https://cds.cern.ch/record/1729545.

- ↑ "Art and sub-atomic particles to collide at CERN" (in en). 4 August 2011. https://www.today.com/news/art-sub-atomic-particles-collide-cern-wbna44018958.

- ↑ "Gianni Motti | "HIGGS, looking for the anti-Motti", CERN, Genève (2005) | Artsy" (in en). https://www.artsy.net/artwork/gianni-motti-higgs-looking-for-the-anti-motti-cern-geneve-1.

- ↑ Wyn Evans, Cerith (2013). Cerith Wyn Evans : the what if? ... scenario (after LG). Eva Wilson, Daniela Zyman, Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary. Berlin: Sternberg Press. ISBN 978-3-943365-88-7. OCLC 876051101. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/876051101.

- ↑ White, Jerry (2017). "John Berger of the Haute-Savoie". Film Quarterly 70 (4): 93–98. doi:10.1525/fq.2017.70.4.93. ISSN 0015-1386. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26413815.

- ↑ "Anselm Kiefer Meets Science At Cern's Monumental Hadron Collider" (in en-GB). https://artlyst.com/news/anselm-kiefer-meets-science-at-cerns-monumental-hadron-collider/.

- ↑ Koek, Ariane (2017-10-02). "In/visible: the inside story of the making of Arts at CERN" (in en). Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 42 (4): 345–358. doi:10.1080/03080188.2017.1381225. ISSN 0308-0188. Bibcode: 2017ISRv...42..345K. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03080188.2017.1381225.

- ↑ Bello, Mónica (2019), Wuppuluri, Shyam; Wu, Dali, eds., "Field Experiences: Fundamental Science and Research in the Arts" (in en), On Art and Science, The Frontiers Collection (Cham: Springer International Publishing): pp. 203–221, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-27577-8_13, ISBN 978-3-030-27576-1, http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-27577-8_13, retrieved 2023-04-06

- ↑ Brown, Malcolm W. (29 December 1998). "Physicists Discover Another Unifying Force: Doo-Wop". The New York Times. https://musiclub.web.cern.ch/MusiClub/bands/cernettes/Press/NYT.pdf.

- ↑ McCabe, Heather (10 February 1999). "Grrl Geeks Rock Out". Wired News. https://musiclub.web.cern.ch/MusiClub/bands/cernettes/Press/Wired.pdf.

- ↑ "Large Hadron Rap". https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j50ZssEojtM.

- ↑ "National Geographic" (in en). https://www.nationalgeographic.com/.

- ↑ Staff and agencies in Geneva (2016-08-17). "Fake human sacrifice filmed at Cern, with pranking scientists suspected". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2016/aug/18/fake-human-sacrifice-filmed-at-cern-with-pranking-scientists-suspected. Retrieved 2023-02-19.

- ↑ Brown, Diana (13 February 2018). "Why Conspiracy Theorists Are Obsessed With CERN". HowStuffWorks. https://science.howstuffworks.com/science-vs-myth/everyday-myths/why-conspiracy-theorists-are-obsessed-with-cern.htm. Retrieved 2023-02-19.

- ↑ "Angels and Demons – the science behind the story". CERN. https://angelsanddemons.web.cern.ch/.

- ↑ "Southparkstudios.com". South Park Studios. 15 April 2009. https://southpark.cc.com/full-episodes/s13e06-pinewood-derby.