Foundations of geometry

Topic: Organization

From HandWiki - Reading time: 38 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 38 min

Foundations of geometry is the study of geometries as axiomatic systems. There are several sets of axioms which give rise to Euclidean geometry or to non-Euclidean geometries. These are fundamental to the study and of historical importance, but there are a great many modern geometries that are not Euclidean which can be studied from this viewpoint. The term axiomatic geometry can be applied to any geometry that is developed from an axiom system, but is often used to mean Euclidean geometry studied from this point of view. The completeness and independence of general axiomatic systems are important mathematical considerations, but there are also issues to do with the teaching of geometry which come into play.

Axiomatic systems

Based on ancient Greek methods, an axiomatic system is a formal description of a way to establish the mathematical truth that flows from a fixed set of assumptions. Although applicable to any area of mathematics, geometry is the branch of elementary mathematics in which this method has most extensively been successfully applied.[1]

There are several components of an axiomatic system.[2]

- Primitives (undefined terms) are the most basic ideas. Typically they include objects and relationships. In geometry, the objects are things like points, lines and planes while a fundamental relationship is that of incidence – of one object meeting or joining with another. The terms themselves are undefined. Hilbert once remarked that instead of points, lines and planes one might just as well talk of tables, chairs and beer mugs.[3] His point being that the primitive terms are just empty shells, place holders if you will, and have no intrinsic properties.

- Axioms (or postulates) are statements about these primitives; for example, any two points are together incident with just one line (i.e. that for any two points, there is just one line which passes through both of them). Axioms are assumed true, and not proven. They are the building blocks of geometric concepts, since they specify the properties that the primitives have.

- The laws of logic.

- The theorems[4] are the logical consequences of the axioms, that is, the statements that can be obtained from the axioms by using the laws of deductive logic.

An interpretation of an axiomatic system is some particular way of giving concrete meaning to the primitives of that system. If this association of meanings makes the axioms of the system true statements, then the interpretation is called a model of the system.[5] In a model, all the theorems of the system are automatically true statements.

Properties of axiomatic systems

In discussing axiomatic systems several properties are often focused on:[6]

- The axioms of an axiomatic system are said to be consistent if no logical contradiction can be derived from them. Except in the simplest systems, consistency is a difficult property to establish in an axiomatic system. On the other hand, if a model exists for the axiomatic system, then any contradiction derivable in the system is also derivable in the model, and the axiomatic system is as consistent as any system in which the model belongs. This property (having a model) is referred to as relative consistency or model consistency.

- An axiom is called independent if it can not be proved or disproved from the other axioms of the axiomatic system. An axiomatic system is said to be independent if each of its axioms is independent. If a true statement is a logical consequence of an axiomatic system, then it will be a true statement in every model of that system. To prove that an axiom is independent of the remaining axioms of the system, it is sufficient to find two models of the remaining axioms, for which the axiom is a true statement in one and a false statement in the other. Independence is not always a desirable property from a pedagogical viewpoint.

- An axiomatic system is called complete if every statement expressible in the terms of the system is either provable or has a provable negation. Another way to state this is that no independent statement can be added to a complete axiomatic system which is consistent with axioms of that system.

- An axiomatic system is categorical if any two models of the system are isomorphic (essentially, there is only one model for the system). A categorical system is necessarily complete, but completeness does not imply categoricity. In some situations categoricity is not a desirable property, since categorical axiomatic systems can not be generalized. For instance, the value of the axiomatic system for group theory is that it is not categorical, so proving a result in group theory means that the result is valid in all the different models for group theory and one doesn't have to reprove the result in each of the non-isomorphic models.

Euclidean geometry

Euclidean geometry is a mathematical system attributed to the Alexandrian Greek mathematician Euclid, which he described (although non-rigorously by modern standards) in his textbook on geometry: the Elements. Euclid's method consists in assuming a small set of intuitively appealing axioms, and deducing many other propositions (theorems) from these. Although many of Euclid's results had been stated by earlier mathematicians,[7] Euclid was the first to show how these propositions could fit into a comprehensive deductive and logical system.[8] The Elements begins with plane geometry, still taught in secondary school as the first axiomatic system and the first examples of formal proof. It goes on to the solid geometry of three dimensions. Much of the Elements states results of what are now called algebra and number theory, explained in geometrical language.[7]

For over two thousand years, the adjective "Euclidean" was unnecessary because no other sort of geometry had been conceived. Euclid's axioms seemed so intuitively obvious (with the possible exception of the parallel postulate) that any theorem proved from them was deemed true in an absolute, often metaphysical, sense. Today, however, many other geometries which are not Euclidean are known, the first ones having been discovered in the early 19th century.

Euclid's Elements

Euclid's Elements is a mathematical and geometric treatise consisting of 13 books written by the ancient Greek mathematician Euclid in Alexandria c. 300 BC. It is a collection of definitions, postulates (axioms), propositions (theorems and constructions), and mathematical proofs of the propositions. The thirteen books cover Euclidean geometry and the ancient Greek version of elementary number theory. With the exception of Autolycus' On the Moving Sphere, the Elements is one of the oldest extant Greek mathematical treatises,[9] and it is the oldest extant axiomatic deductive treatment of mathematics. It has proven instrumental in the development of logic and modern science.

Euclid's Elements has been referred to as the most successful[10][11] and influential[12] textbook ever written. Being first set in type in Venice in 1482, it is one of the very earliest mathematical works to be printed after the invention of the printing press and was estimated by Carl Benjamin Boyer to be second only to the Bible in the number of editions published,[12] with the number reaching well over one thousand.[13] For centuries, when the quadrivium was included in the curriculum of all university students, knowledge of at least part of Euclid's Elements was required of all students. Not until the 20th century, by which time its content was universally taught through other school textbooks, did it cease to be considered something all educated people had read.[14]

The Elements are mainly a systematization of earlier knowledge of geometry. It is assumed that its superiority over earlier treatments was recognized, with the consequence that there was little interest in preserving the earlier ones, and they are now nearly all lost.

Books I–IV and VI discuss plane geometry. Many results about plane figures are proved, e.g., If a triangle has two equal angles, then the sides subtended by the angles are equal. The Pythagorean theorem is proved.[15]

Books V and VII–X deal with number theory, with numbers treated geometrically via their representation as line segments with various lengths. Notions such as prime numbers and rational and irrational numbers are introduced. The infinitude of prime numbers is proved.

Books XI–XIII concern solid geometry. A typical result is the 1:3 ratio between the volume of a cone and a cylinder with the same height and base.

Near the beginning of the first book of the Elements, Euclid gives five postulates (axioms) for plane geometry, stated in terms of constructions (as translated by Thomas Heath):[16]

"Let the following be postulated":

- "To draw a straight line from any point to any point."

- "To produce [extend] a finite straight line continuously in a straight line."

- "To describe a circle with any centre and distance [radius]."

- "That all right angles are equal to one another."

- The parallel postulate: "That, if a straight line falling on two straight lines make the interior angles on the same side less than two right angles, the two straight lines, if produced indefinitely, meet on that side on which are the angles less than the two right angles."

Although Euclid's statement of the postulates only explicitly asserts the existence of the constructions, they are also assumed to produce unique objects.

The success of the Elements is due primarily to its logical presentation of most of the mathematical knowledge available to Euclid. Much of the material is not original to him, although many of the proofs are supposedly his. Euclid's systematic development of his subject, from a small set of axioms to deep results, and the consistency of his approach throughout the Elements, encouraged its use as a textbook for about 2,000 years. The Elements still influences modern geometry books. Further, its logical axiomatic approach and rigorous proofs remain the cornerstone of mathematics.

A critique of Euclid

The standards of mathematical rigor have changed since Euclid wrote the Elements.[17] Modern attitudes towards, and viewpoints of, an axiomatic system can make it appear that Euclid was in some way sloppy or careless in his approach to the subject, but this is an ahistorical illusion. It is only after the foundations were being carefully examined in response to the introduction of non-Euclidean geometry that what we now consider flaws began to emerge. Mathematician and historian W. W. Rouse Ball put these criticisms in perspective, remarking that "the fact that for two thousand years [the Elements] was the usual text-book on the subject raises a strong presumption that it is not unsuitable for that purpose."[18]

Some of the main issues with Euclid's presentation are:

- Lack of recognition of the concept of primitive terms, objects and notions that must be left undefined in the development of an axiomatic system.[19]

- The use of superposition in some proofs without there being an axiomatic justification of this method.[20]

- Lack of a concept of continuity, which is needed to prove the existence of some points and lines that Euclid constructs.[20]

- Lack of clarity on whether a straight line is infinite or boundaryless in the second postulate.[21]

- Lack of the concept of betweenness used, among other things, for distinguishing between the inside and outside of various figures.[22]

Euclid's list of axioms in the Elements was not exhaustive, but represented the principles that seemed the most important. His proofs often invoke axiomatic notions that were not originally presented in his list of axioms.[23] He does not go astray and prove erroneous things because of this, since he is making use of implicit assumptions whose validity appears to be justified by the diagrams which accompany his proofs. Later mathematicians have incorporated Euclid's implicit axiomatic assumptions in the list of formal axioms, thereby greatly extending that list.[24]

For example, in the first construction of Book 1, Euclid used a premise that was neither postulated nor proved: that two circles with centers at the distance of their radius will intersect in two points.[25] Later, in the fourth construction, he used superposition (moving the triangles on top of each other) to prove that if two sides and their angles are equal then they are congruent; during these considerations he uses some properties of superposition, but these properties are not described explicitly in the treatise. If superposition is to be considered a valid method of geometric proof, all of geometry would be full of such proofs. For example, propositions I.1 to I.3 can be proved trivially by using superposition.[26]

To address these issues in Euclid's work, later authors have either attempted to fill in the holes in Euclid's presentation – the most notable of these attempts is due to D. Hilbert – or to organize the axiom system around different concepts, as G.D. Birkhoff has done.

Pasch and Peano

The German mathematician Moritz Pasch (1843–1930) was the first to accomplish the task of putting Euclidean geometry on a firm axiomatic footing.[27] In his book, Vorlesungen über neuere Geometrie published in 1882, Pasch laid the foundations of the modern axiomatic method. He originated the concept of primitive notion (which he called Kernbegriffe) and together with the axioms (Kernsätzen) he constructs a formal system which is free from any intuitive influences. According to Pasch, the only place where intuition should play a role is in deciding what the primitive notions and axioms should be. Thus, for Pasch, point is a primitive notion but line (straight line) is not, since we have good intuition about points but no one has ever seen or had experience with an infinite line. The primitive notion that Pasch uses in its place is line segment.

Pasch observed that the ordering of points on a line (or equivalently containment properties of line segments) is not properly resolved by Euclid's axioms; thus, Pasch's theorem, stating that if two line segment containment relations hold then a third one also holds, cannot be proven from Euclid's axioms. The related Pasch's axiom concerns the intersection properties of lines and triangles.

Pasch's work on the foundations set the standard for rigor, not only in geometry but also in the wider context of mathematics. His breakthrough ideas are now so commonplace that it is difficult to remember that they had a single originator. Pasch's work directly influenced many other mathematicians, in particular D. Hilbert and the Italian mathematician Giuseppe Peano (1858–1932). Peano's 1889 work on geometry, largely a translation of Pasch's treatise into the notation of symbolic logic (which Peano invented), uses the primitive notions of point and betweeness.[28] Peano breaks the empirical tie in the choice of primitive notions and axioms that Pasch required. For Peano, the entire system is purely formal, divorced from any empirical input.[29]

Pieri and the Italian school of geometers

The Italian mathematician Mario Pieri (1860–1913) took a different approach and considered a system in which there were only two primitive notions, that of point and of motion.[30] Pasch had used four primitives and Peano had reduced this to three, but both of these approaches relied on some concept of betweeness which Pieri replaced by his formulation of motion. In 1905 Pieri gave the first axiomatic treatment of complex projective geometry which did not start by building real projective geometry.

Pieri was a member of a group of Italian geometers and logicians that Peano had gathered around himself in Turin. This group of assistants, junior colleagues and others were dedicated to carrying out Peano's logico–geometrical program of putting the foundations of geometry on firm axiomatic footing based on Peano's logical symbolism. Besides Pieri, Burali-Forti, Padoa and Fano were in this group. In 1900 there were two international conferences held back-to-back in Paris, the International Congress of Philosophy and the Second International Congress of Mathematicians. This group of Italian mathematicians was very much in evidence at these congresses, pushing their axiomatic agenda.[31] Padoa gave a well regarded talk and Peano, in the question period after David Hilbert's famous address on unsolved problems, remarked that his colleagues had already solved Hilbert's second problem.

Hilbert's axioms

At the University of Göttingen, during the 1898–1899 winter term, the eminent German mathematician David Hilbert (1862–1943) presented a course of lectures on the foundations of geometry. At the request of Felix Klein, Professor Hilbert was asked to write up the lecture notes for this course in time for the summer 1899 dedication ceremony of a monument to C.F. Gauss and Wilhelm Weber to be held at the university. The rearranged lectures were published in June 1899 under the title Grundlagen der Geometrie (Foundations of Geometry). The influence of the book was immediate. According to (Eves 1963):

By developing a postulate set for Euclidean geometry that does not depart too greatly in spirit from Euclid's own, and by employing a minimum of symbolism, Hilbert succeeded in convincing mathematicians to a far greater extent than had Pasch and Peano, of the purely hypothetico-deductive nature of geometry. But the influence of Hilbert's work went far beyond this, for, backed by the author's great mathematical authority, it firmly implanted the postulational method, not only in the field of geometry, but also in essentially every other branch of mathematics. The stimulus to the development of the foundations of mathematics provided by Hilbert's little book is difficult to overestimate. Lacking the strange symbolism of the works of Pasch and Peano, Hilbert's work can be read, in great part, by any intelligent student of high school geometry.

It is difficult to specify the axioms used by Hilbert without referring to the publication history of the Grundlagen since Hilbert changed and modified them several times. The original monograph was quickly followed by a French translation, in which Hilbert added V.2, the Completeness Axiom. An English translation, authorized by Hilbert, was made by E.J. Townsend and copyrighted in 1902.[32] This translation incorporated the changes made in the French translation and so is considered to be a translation of the 2nd edition. Hilbert continued to make changes in the text and several editions appeared in German. The 7th edition was the last to appear in Hilbert's lifetime. New editions followed the 7th, but the main text was essentially not revised. The modifications in these editions occur in the appendices and in supplements. The changes in the text were large when compared to the original and a new English translation was commissioned by Open Court Publishers, who had published the Townsend translation. So, the 2nd English Edition was translated by Leo Unger from the 10th German edition in 1971.[33] This translation incorporates several revisions and enlargements of the later German editions by Paul Bernays. The differences between the two English translations are due not only to Hilbert, but also to differing choices made by the two translators. What follows will be based on the Unger translation.

Hilbert's axiom system is constructed with six primitive notions: point, line, plane, betweenness, lies on (containment), and congruence.

All points, lines, and planes in the following axioms are distinct unless otherwise stated.

- I. Incidence

- For every two points A and B there exists a line a that contains them both. We write AB = a or BA = a. Instead of “contains,” we may also employ other forms of expression; for example, we may say “A lies upon a”, “A is a point of a”, “a goes through A and through B”, “a joins A to B”, etc. If A lies upon a and at the same time upon another line b, we make use also of the expression: “The lines a and b have the point A in common,” etc.

- For every two points there exists no more than one line that contains them both; consequently, if AB = a and AC = a, where B ≠ C, then also BC = a.

- There exist at least two points on a line. There exist at least three points that do not lie on a line.

- For every three points A, B, C not situated on the same line there exists a plane α that contains all of them. For every plane there exists a point which lies on it. We write ABC = α. We employ also the expressions: “A, B, C, lie in α”; “A, B, C are points of α”, etc.

- For every three points A, B, C which do not lie in the same line, there exists no more than one plane that contains them all.

- If two points A, B of a line a lie in a plane α, then every point of a lies in α. In this case we say: “The line a lies in the plane α,” etc.

- If two planes α, β have a point A in common, then they have at least a second point B in common.

- There exist at least four points not lying in a plane.

- II. Order

- If a point B lies between points A and C, B is also between C and A, and there exists a line containing the distinct points A,B,C.

- If A and C are two points of a line, then there exists at least one point B lying between A and C.

- Of any three points situated on a line, there is no more than one which lies between the other two.

- Pasch's Axiom: Let A, B, C be three points not lying in the same line and let a be a line lying in the plane ABC and not passing through any of the points A, B, C. Then, if the line a passes through a point of the segment AB, it will also pass through either a point of the segment BC or a point of the segment AC.

- III. Congruence

- If A, B are two points on a line a, and if A′ is a point upon the same or another line a′ , then, upon a given side of A′ on the straight line a′ , we can always find a point B′ so that the segment AB is congruent to the segment A′B′ . We indicate this relation by writing AB ≅ A′ B′. Every segment is congruent to itself; that is, we always have AB ≅ AB.

We can state the above axiom briefly by saying that every segment can be laid off upon a given side of a given point of a given straight line in at least one way. - If a segment AB is congruent to the segment A′B′ and also to the segment A″B″, then the segment A′B′ is congruent to the segment A″B″; that is, if AB ≅ A′B′ and AB ≅ A″B″, then A′B′ ≅ A″B″.

- Let AB and BC be two segments of a line a which have no points in common aside from the point B, and, furthermore, let A′B′ and B′C′ be two segments of the same or of another line a′ having, likewise, no point other than B′ in common. Then, if AB ≅ A′B′ and BC ≅ B′C′, we have AC ≅ A′C′.

- Let an angle ∠ (h,k) be given in the plane α and let a line a′ be given in a plane α′. Suppose also that, in the plane α′, a definite side of the straight line a′ be assigned. Denote by h′ a ray of the straight line a′ emanating from a point O′ of this line. Then in the plane α′ there is one and only one ray k′ such that the angle ∠ (h, k), or ∠ (k, h), is congruent to the angle ∠ (h′, k′) and at the same time all interior points of the angle ∠ (h′, k′) lie upon the given side of a′. We express this relation by means of the notation ∠ (h, k) ≅ ∠ (h′, k′).

- If the angle ∠ (h, k) is congruent to the angle ∠ (h′, k′) and to the angle ∠ (h″, k″), then the angle ∠ (h′, k′) is congruent to the angle ∠ (h″, k″); that is to say, if ∠ (h, k) ≅ ∠ (h′, k′) and ∠ (h, k) ≅ ∠ (h″, k″), then ∠ (h′, k′) ≅ ∠ (h″, k″).

- IV. Parallels

- (Euclid's Axiom):[34] Let a be any line and A a point not on it. Then there is at most one line in the plane, determined by a and A, that passes through A and does not intersect a.

- V. Continuity

- Axiom of Archimedes. If AB and CD are any segments then there exists a number n such that n segments CD constructed contiguously from A, along the ray from A through B, will pass beyond the point B.

- Axiom of line completeness. An extension of a set of points on a line with its order and congruence relations that would preserve the relations existing among the original elements as well as the fundamental properties of line order and congruence that follows from Axioms I–III and from V-1 is impossible.

Changes in Hilbert's axioms

When the monograph of 1899 was translated into French, Hilbert added:

- V.2 Axiom of completeness. To a system of points, straight lines, and planes, it is impossible to add other elements in such a manner that the system thus generalized shall form a new geometry obeying all of the five groups of axioms. In other words, the elements of geometry form a system which is not susceptible of extension, if we regard the five groups of axioms as valid.

This axiom is not needed for the development of Euclidean geometry, but is needed to establish a bijection between the real numbers and the points on a line.[35] This was an essential ingredient in Hilbert's proof of the consistency of his axiom system.

By the 7th edition of the Grundlagen, this axiom had been replaced by the axiom of line completeness given above and the old axiom V.2 became Theorem 32.

Also to be found in the 1899 monograph (and appearing in the Townsend translation) is:

- II.4. Any four points A, B, C, D of a line can always be labeled so that B shall lie between A and C and also between A and D, and, furthermore, that C shall lie between A and D and also between B and D.

However, E.H. Moore and R.L. Moore independently proved that this axiom is redundant, and the former published this result in an article appearing in the Transactions of the American Mathematical Society in 1902.[36] Hilbert moved the axiom to Theorem 5 and renumbered the axioms accordingly (old axiom II-5 (Pasch's axiom) now became II-4).

While not as dramatic as these changes, most of the remaining axioms were also modified in form and/or function over the course of the first seven editions.

Consistency and independence

Going beyond the establishment of a satisfactory set of axioms, Hilbert also proved the consistency of his system relative to the theory of real numbers by constructing a model of his axiom system from the real numbers. He proved the independence of some of his axioms by constructing models of geometries which satisfy all except the one axiom under consideration. Thus, there are examples of geometries satisfying all except the Archimedean axiom V.1 (non-Archimedean geometries), all except the parallel axiom IV.1 (non-Euclidean geometries) and so on. Using the same technique he also showed how some important theorems depended on certain axioms and were independent of others. Some of his models were very complex and other mathematicians tried to simplify them. For instance, Hilbert's model for showing the independence of Desargues theorem from certain axioms ultimately led Ray Moulton to discover the non-Desarguesian Moulton plane. These investigations by Hilbert virtually inaugurated the modern study of abstract geometry in the twentieth century.[37]

Birkhoff's axioms

In 1932, G. D. Birkhoff created a set of four postulates of Euclidean geometry sometimes referred to as Birkhoff's axioms.[38] These postulates are all based on basic geometry that can be experimentally verified with a scale and protractor. In a radical departure from the synthetic approach of Hilbert, Birkhoff was the first to build the foundations of geometry on the real number system.[39] It is this powerful assumption that permits the small number of axioms in this system.

Postulates

Birkhoff uses four undefined terms: point, line, distance and angle. His postulates are:[40]

Postulate I: Postulate of Line Measure. The points A, B, ... of any line can be put into 1:1 correspondence with the real numbers x so that |xB −x A| = d(A, B) for all points A and B.

Postulate II: Point-Line Postulate. There is one and only one straight line, ℓ, that contains any two given distinct points P and Q.

Postulate III: Postulate of Angle Measure. The rays {ℓ, m, n, ...} through any point O can be put into 1:1 correspondence with the real numbers a (mod 2π) so that if A and B are points (not equal to O) of ℓ and m, respectively, the difference am − aℓ (mod 2π) of the numbers associated with the lines ℓ and m is AOB. Furthermore, if the point B on m varies continuously in a line r not containing the vertex O, the number am varies continuously also.

Postulate IV: Postulate of Similarity. If in two triangles ABC and A'B'C' and for some constant k > 0, d(A', B' ) = kd(A, B), d(A', C' ) = kd(A, C) and B'A'C' = ±BAC, then d(B', C' ) = kd(B, C), C'B'A' = ±CBA, and A'C'B' = ±ACB.

School geometry

Whether or not it is wise to teach Euclidean geometry from an axiomatic viewpoint at the high school level has been a matter of debate. There have been many attempts to do so and not all of them have been successful. In 1904, George Bruce Halsted published a high school geometry text based on Hilbert's axiom set.[41] Logical criticisms of this text led to a highly revised second edition.[42] In reaction to the launching of the Russian satellite Sputnik there was a call in the United States to revise the school mathematics curriculum. From this effort there arose the New Math program of the 1960s. With this as a background, many individuals and groups set about to provide textual material for geometry classes based on an axiomatic approach.

Mac Lane's axioms

Saunders Mac Lane (1909–2005), a mathematician,[43] wrote a paper in 1959 in which he proposed a set of axioms for Euclidean geometry in the spirit of Birkhoff's treatment using a distance function to associate real numbers with line segments.[44] This was not the first attempt to base a school level treatment on Birkhoff's system, in fact, Birkhoff and Ralph Beatley had written a high school text in 1940[45] which developed Euclidean geometry from five axioms and the ability to measure line segments and angles. However, in order to gear the treatment to a high school audience, some mathematical and logical arguments were either ignored or slurred over.[42]

In Mac Lane's system there are four primitive notions (undefined terms): point, distance, line and angle measure. There are also 14 axioms, four giving the properties of the distance function, four describing properties of lines, four discussing angles (which are directed angles in this treatment), a similarity axiom (essentially the same as Birkhoff's) and a continuity axiom which can be used to derive the Crossbar theorem and its converse.[46] The increased number of axioms has the pedagogical advantage of making early proofs in the development easier to follow and the use of a familiar metric permits a rapid advancement through basic material so that the more "interesting" aspects of the subject can be gotten to sooner.

SMSG (School Mathematics Study Group) axioms

In the 1960s a new set of axioms for Euclidean geometry, suitable for American high school geometry courses, was introduced by the School Mathematics Study Group (SMSG), as a part of the New math curricula. This set of axioms follows the Birkhoff model of using the real numbers to gain quick entry into the geometric fundamentals. However, whereas Birkhoff tried to minimize the number of axioms used, and most authors were concerned with the independence of the axioms in their treatments, the SMSG axiom list was intentionally made large and redundant for pedagogical reasons.[47] The SMSG only produced a mimeographed text using these axioms,[48] but Edwin E. Moise, a member of the SMSG, wrote a high school text based on this system,[49] and a college level text, (Moise 1974), with some of the redundancy removed and modifications made to the axioms for a more sophisticated audience.[50]

There are eight undefined terms: point, line, plane, lies on, angle measure, distance, area and volume. The 22 axioms of this system are given individual names for ease of reference. Amongst these are to be found: the Ruler Postulate, the Ruler Placement Postulate, the Plane Separation Postulate, the Angle Addition Postulate, the Side angle side (SAS) Postulate, the Parallel Postulate (in Playfair's form), and Cavalieri's principle.[51]

UCSMP (University of Chicago School Mathematics Project) axioms

Although much of the New math curriculum has been drastically modified or abandoned, the geometry portion has remained relatively stable in the United States. Modern American high school textbooks use axiom systems that are very similar to those of the SMSG. For example, the texts produced by the University of Chicago School Mathematics Project (UCSMP) use a system which, besides some updating of language, differs mainly from the SMSG system in that it includes some transformation concepts under its "Reflection Postulate".[47]

There are only three undefined terms: point, line and plane. There are eight "postulates", but most of these have several parts (which are generally called assumptions in this system). Counting these parts, there are 32 axioms in this system. Amongst the postulates can be found the point-line-plane postulate, the Triangle inequality postulate, postulates for distance, angle measurement, corresponding angles, area and volume, and the Reflection postulate. The reflection postulate is used as a replacement for the SAS postulate of SMSG system.[52]

Other systems

Oswald Veblen (1880 – 1960) provided a new axiom system in 1904 when he replaced the concept of "betweeness", as used by Hilbert and Pasch, with a new primitive, order. This permitted several primitive terms used by Hilbert to become defined entities, reducing the number of primitive notions to two, point and order.[37]

Many other axiomatic systems for Euclidean geometry have been proposed over the years. A comparison of many of these can be found in a 1927 monograph by Henry George Forder.[53] Forder also gives, by combining axioms from different systems, his own treatment based on the two primitive notions of point and order. He also provides a more abstract treatment of one of Pieri's systems (from 1909) based on the primitives point and congruence.[42]

Starting with Peano, there has been a parallel thread of interest amongst logicians concerning the axiomatic foundations of Euclidean geometry. This can be seen, in part, in the notation used to describe the axioms. Pieri claimed that even though he wrote in the traditional language of geometry, he was always thinking in terms of the logical notation introduced by Peano, and used that formalism to see how to prove things. A typical example of this type of notation can be found in the work of E. V. Huntington (1874 – 1952) who, in 1913,[54] produced an axiomatic treatment of three-dimensional Euclidean geometry based upon the primitive notions of sphere and inclusion (one sphere lying within another).[42] Beyond notation there is also interest in the logical structure of the theory of geometry. Alfred Tarski proved that a portion of geometry, which he called elementary geometry, is a first order logical theory (see Tarski's axioms).

Modern text treatments of the axiomatic foundations of Euclidean geometry follow the pattern of H.G. Forder and Gilbert de B. Robinson[55] who mix and match axioms from different systems to produce different emphases. (Venema 2006) is a modern example of this approach.

Non-Euclidean geometry

In view of the role which mathematics plays in science and implications of scientific knowledge for all of our beliefs, revolutionary changes in man's understanding of the nature of mathematics could not but mean revolutionary changes in his understanding of science, doctrines of philosophy, religious and ethical beliefs, and, in fact, all intellectual disciplines.[56]

In the first half of the nineteenth century a revolution took place in the field of geometry that was as scientifically important as the Copernican revolution in astronomy and as philosophically profound as the Darwinian theory of evolution in its impact on the way we think. This was the consequence of the discovery of non-Euclidean geometry.[57] For over two thousand years, starting in the time of Euclid, the postulates which grounded geometry were considered self-evident truths about physical space. Geometers thought that they were deducing other, more obscure truths from them, without the possibility of error. This view became untenable with the development of hyperbolic geometry. There were now two incompatible systems of geometry (and more came later) that were self-consistent and compatible with the observable physical world. "From this point on, the whole discussion of the relation between geometry and physical space was carried on in quite different terms."(Moise 1974)

To obtain a non-Euclidean geometry, the parallel postulate (or its equivalent) must be replaced by its negation. Negating the Playfair's axiom form, since it is a compound statement (... there exists one and only one ...), can be done in two ways. Either there will exist more than one line through the point parallel to the given line or there will exist no lines through the point parallel to the given line. In the first case, replacing the parallel postulate (or its equivalent) with the statement "In a plane, given a point P and a line ℓ not passing through P, there exist two lines through P which do not meet ℓ" and keeping all the other axioms, yields hyperbolic geometry.[58] The second case is not dealt with as easily. Simply replacing the parallel postulate with the statement, "In a plane, given a point P and a line ℓ not passing through P, all the lines through P meet ℓ", does not give a consistent set of axioms. This follows since parallel lines exist in absolute geometry,[59] but this statement would say that there are no parallel lines. This problem was known (in a different guise) to Khayyam, Saccheri and Lambert and was the basis for their rejecting what was known as the "obtuse angle case". In order to obtain a consistent set of axioms which includes this axiom about having no parallel lines, some of the other axioms must be tweaked. The adjustments to be made depend upon the axiom system being used. Amongst others these tweaks will have the effect of modifying Euclid's second postulate from the statement that line segments can be extended indefinitely to the statement that lines are unbounded. Riemann's elliptic geometry emerges as the most natural geometry satisfying this axiom.

It was Gauss who coined the term "non-Euclidean geometry".[60] He was referring to his own, unpublished work, which today we call hyperbolic geometry. Several authors still consider "non-Euclidean geometry" and "hyperbolic geometry" to be synonyms. In 1871, Felix Klein, by adapting a metric discussed by Arthur Cayley in 1852, was able to bring metric properties into a projective setting and was thus able to unify the treatments of hyperbolic, euclidean and elliptic geometry under the umbrella of projective geometry.[61] Klein is responsible for the terms "hyperbolic" and "elliptic" (in his system he called Euclidean geometry "parabolic", a term which has not survived the test of time and is used today only in a few disciplines.) His influence has led to the common usage of the term "non-Euclidean geometry" to mean either "hyperbolic" or "elliptic" geometry.

There are some mathematicians who would extend the list of geometries that should be called "non-Euclidean" in various ways. In other disciplines, most notably mathematical physics, where Klein's influence was not as strong, the term "non-Euclidean" is often taken to mean not Euclidean.

Euclid's parallel postulate

For two thousand years, many attempts were made to prove the parallel postulate using Euclid's first four postulates. A possible reason that such a proof was so highly sought after was that, unlike the first four postulates, the parallel postulate isn't self-evident. If the order the postulates were listed in the Elements is significant, it indicates that Euclid included this postulate only when he realised he could not prove it or proceed without it.[62] Many attempts were made to prove the fifth postulate from the other four, many of them being accepted as proofs for long periods of time until the mistake was found. Invariably the mistake was assuming some 'obvious' property which turned out to be equivalent to the fifth postulate. Eventually it was realized that this postulate may not be provable from the other four. According to (Trudeau 1987) this opinion about the parallel postulate (Postulate 5) does appear in print:

Apparently the first to do so was G. S. Klügel (1739–1812), a doctoral student at the University of Gottingen, with the support of his teacher A. G. Kästner, in the former's 1763 dissertation Conatuum praecipuorum theoriam parallelarum demonstrandi recensio (Review of the Most Celebrated Attempts at Demonstrating the Theory of Parallels). In this work Klügel examined 28 attempts to prove Postulate 5 (including Saccheri's), found them all deficient, and offered the opinion that Postulate 5 is unprovable and is supported solely by the judgment of our senses.

The beginning of the 19th century would finally witness decisive steps in the creation of non-Euclidean geometry. Circa 1813, Carl Friedrich Gauss and independently around 1818, the German professor of law Ferdinand Karl Schweikart[63] had the germinal ideas of non-Euclidean geometry worked out, but neither published any results. Then, around 1830, the Hungarian mathematician János Bolyai and the Russia n mathematician Nikolai Ivanovich Lobachevsky separately published treatises on what we today call hyperbolic geometry. Consequently, hyperbolic geometry has been called Bolyai-Lobachevskian geometry, as both mathematicians, independent of each other, are the basic authors of non-Euclidean geometry. Gauss mentioned to Bolyai's father, when shown the younger Bolyai's work, that he had developed such a geometry several years before,[64] though he did not publish. While Lobachevsky created a non-Euclidean geometry by negating the parallel postulate, Bolyai worked out a geometry where both the Euclidean and the hyperbolic geometry are possible depending on a parameter k. Bolyai ends his work by mentioning that it is not possible to decide through mathematical reasoning alone if the geometry of the physical universe is Euclidean or non-Euclidean; this is a task for the physical sciences. The independence of the parallel postulate from Euclid's other axioms was finally demonstrated by Eugenio Beltrami in 1868.[65]

The various attempted proofs of the parallel postulate produced a long list of theorems that are equivalent to the parallel postulate. Equivalence here means that in the presence of the other axioms of the geometry each of these theorems can be assumed to be true and the parallel postulate can be proved from this altered set of axioms. This is not the same as logical equivalence.[66] In different sets of axioms for Euclidean geometry, any of these can replace the Euclidean parallel postulate.[67] The following partial list indicates some of these theorems that are of historical interest.[68]

- Parallel straight lines are equidistant. (Poseidonios, 1st century B.C.)

- All the points equidistant from a given straight line, on a given side of it, constitute a straight line. (Christoph Clavius, 1574)

- Playfair's axiom. In a plane, there is at most one line that can be drawn parallel to another given one through an external point. (Proclus, 5th century, but popularized by John Playfair, late 18th century)

- The sum of the angles in every triangle is 180° (Gerolamo Saccheri, 1733; Adrien-Marie Legendre, early 19th century)

- There exists a triangle whose angles add up to 180°. (Gerolamo Saccheri, 1733; Adrien-Marie Legendre, early 19th century)

- There exists a pair of similar, but not congruent, triangles. (Gerolamo Saccheri, 1733)

- Every triangle can be circumscribed. (Adrien-Marie Legendre, Farkas Bolyai, early 19th century)

- If three angles of a quadrilateral are right angles, then the fourth angle is also a right angle. (Alexis-Claude Clairaut, 1741; Johann Heinrich Lambert, 1766)

- There exists a quadrilateral in which all angles are right angles. (Geralamo Saccheri, 1733)

- Wallis' postulate. On a given finite straight line it is always possible to construct a triangle similar to a given triangle. (John Wallis, 1663; Lazare-Nicholas-Marguerite Carnot, 1803; Adrien-Marie Legendre, 1824)

- There is no upper limit to the area of a triangle. (Carl Friedrich Gauss, 1799)

- The summit angles of the Saccheri quadrilateral are 90°. (Geralamo Saccheri, 1733)

- Proclus' axiom. If a line intersects one of two parallel lines, both of which are coplanar with the original line, then it also intersects the other. (Proclus, 5th century)

Neutral (or absolute) geometry

Absolute geometry is a geometry based on an axiom system consisting of all the axioms giving Euclidean geometry except for the parallel postulate or any of its alternatives.[69] The term was introduced by János Bolyai in 1832.[70] It is sometimes referred to as neutral geometry,[71] as it is neutral with respect to the parallel postulate.

Relation to other geometries

In Euclid's Elements, the first 28 propositions and Proposition I.31 avoid using the parallel postulate, and therefore are valid theorems in absolute geometry.[72] Proposition I.31 proves the existence of parallel lines (by construction). Also, the Saccheri–Legendre theorem, which states that the sum of the angles in a triangle is at most 180°, can be proved.

The theorems of absolute geometry hold in hyperbolic geometry as well as in Euclidean geometry.[73]

Absolute geometry is inconsistent with elliptic geometry: in elliptic geometry there are no parallel lines at all, but in absolute geometry parallel lines do exist. Also, in elliptic geometry, the sum of the angles in any triangle is greater than 180°.

Incompleteness

Logically, the axioms do not form a complete theory since one can add extra independent axioms without making the axiom system inconsistent. One can extend absolute geometry by adding different axioms about parallelism and get incompatible but consistent axiom systems, giving rise to Euclidean and hyperbolic geometry. Thus every theorem of absolute geometry is a theorem of hyperbolic geometry and Euclidean geometry. However the converse is not true. Also, absolute geometry is not a categorical theory, since it has models that are not isomorphic.[citation needed]

Hyperbolic geometry

In the axiomatic approach to hyperbolic geometry (also referred to as Lobachevskian geometry or Bolyai–Lobachevskian geometry), one additional axiom is added to the axioms giving absolute geometry. The new axiom is Lobachevsky's parallel postulate (also known as the characteristic postulate of hyperbolic geometry):[74]

- Through a point not on a given line there exists (in the plane determined by this point and line) at least two lines which do not meet the given line.

With this addition, the axiom system is now complete.

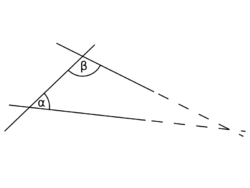

Although the new axiom asserts only the existence of two lines, it is readily established that there are an infinite number of lines through the given point which do not meet the given line. Given this plenitude, one must be careful with terminology in this setting, as the term parallel line no longer has the unique meaning that it has in Euclidean geometry. Specifically, let P be a point not on a given line . Let PA be the perpendicular drawn from P to (meeting at point A). The lines through P fall into two classes, those that meet and those that don't. The characteristic postulate of hyperbolic geometry says that there are at least two lines of the latter type. Of the lines which don't meet , there will be (on each side of PA) a line making the smallest angle with PA. Sometimes these lines are referred to as the first lines through P which don't meet and are variously called limiting, asymptotic or parallel lines (when this last term is used, these are the only parallel lines). All other lines through P which do not meet are called non-intersecting or ultraparallel lines.

Since hyperbolic geometry and Euclidean geometry are both built on the axioms of absolute geometry, they share many properties and propositions. However, the consequences of replacing the parallel postulate of Euclidean geometry with the characteristic postulate of hyperbolic geometry can be dramatic. To mention a few of these:

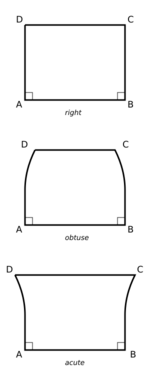

- A Lambert quadrilateral is a quadrilateral which has three right angles. The fourth angle of a Lambert quadrilateral is acute if the geometry is hyperbolic, and a right angle if the geometry is Euclidean. Furthermore, rectangles can exist (a statement equivalent to the parallel postulate) only in Euclidean geometry.

- A Saccheri quadrilateral is a quadrilateral which has two sides of equal length, both perpendicular to a side called the base. The other two angles of a Saccheri quadrilateral are called the summit angles and they have equal measure. The summit angles of a Saccheri quadrilateral are acute if the geometry is hyperbolic, and right angles if the geometry is Euclidean.

- The sum of the measures of the angles of any triangle is less than 180° if the geometry is hyperbolic, and equal to 180° if the geometry is Euclidean. The defect of a triangle is the numerical value (180° – sum of the measures of the angles of the triangle). This result may also be stated as: the defect of triangles in hyperbolic geometry is positive, and the defect of triangles in Euclidean geometry is zero.

- The area of a triangle in hyperbolic geometry is bounded while triangles exist with arbitrarily large areas in Euclidean geometry.

- The set of points on the same side and equally far from a given straight line themselves form a line in Euclidean geometry, but don't in hyperbolic geometry (they form a hypercycle.)

Advocates of the position that Euclidean geometry is the one and only "true" geometry received a setback when, in a memoir published in 1868, "Fundamental theory of spaces of constant curvature",[75] Eugenio Beltrami gave an abstract proof of equiconsistency of hyperbolic and Euclidean geometry for any dimension. He accomplished this by introducing several models of non-Euclidean geometry that are now known as the Beltrami–Klein model, the Poincaré disk model, and the Poincaré half-plane model, together with transformations that relate them. For the half-plane model, Beltrami cited a note by Liouville in the treatise of Monge on differential geometry. Beltrami also showed that n-dimensional Euclidean geometry is realized on a horosphere of the (n + 1)-dimensional hyperbolic space, so the logical relation between consistency of the Euclidean and the non-Euclidean geometries is symmetric.

Elliptic geometry

Another way to modify the Euclidean parallel postulate is to assume that there are no parallel lines in a plane. Unlike the situation with hyperbolic geometry, where we just add one new axiom, we can not obtain a consistent system by adding this statement as a new axiom to the axioms of absolute geometry. This follows since parallel lines provably exist in absolute geometry. Other axioms must be changed.

Starting with Hilbert's axioms the necessary changes involve removing Hilbert's four axioms of order and replacing them with these seven axioms of separation concerned with a new undefined relation.[76]

There is an undefined (primitive) relation between four points, A, B, C and D denoted by (A,C|B,D) and read as "A and C separate B and D",[77] satisfying these axioms:

- If (A,B|C,D), then the points A, B, C and D are collinear and distinct.

- If (A,B|C,D), then (C,D|A,B) and (B,A|D,C).

- If (A,B|C,D), then not (A,C|B,D).

- If points A, B, C and D are collinear and distinct then (A,B|C,D) or (A,C|B,D) or (A,D|B,C).

- If points A, B, and C are collinear and distinct, then there exists a point D such that (A,B|C,D).

- For any five distinct collinear points A, B, C, D and E, if (A,B|D,E), then either (A,B|C,D) or (A,B|C,E).

- Perspectivities preserve separation.

Since the Hilbert notion of "betweeness" has been removed, terms which were defined using that concept need to be redefined.[78] Thus, a line segment AB defined as the points A and B and all the points between A and B in absolute geometry, needs to be reformulated. A line segment in this new geometry is determined by three collinear points A, B and C and consists of those three points and all the points not separated from B by A and C. There are further consequences. Since two points do not determine a line segment uniquely, three noncollinear points do not determine a unique triangle, and the definition of triangle has to be reformulated.

Once these notions have been redefined, the other axioms of absolute geometry (incidence, congruence and continuity) all make sense and are left alone. Together with the new axiom on the nonexistence of parallel lines we have a consistent system of axioms giving a new geometry. The geometry that results is called (plane) Elliptic geometry.

Even though elliptic geometry is not an extension of absolute geometry (as Euclidean and hyperbolic geometry are), there is a certain "symmetry" in the propositions of the three geometries that reflects a deeper connection which was observed by Felix Klein. Some of the propositions which exhibit this property are:

- The fourth angle of a Lambert quadrilateral is an obtuse angle in elliptic geometry.

- The summit angles of a Saccheri quadrilateral are obtuse in elliptic geometry.

- The sum of the measures of the angles of any triangle is greater than 180° if the geometry is elliptic. That is, the defect of a triangle is negative.[79]

- All the lines perpendicular to a given line meet at a common point in elliptic geometry, called the pole of the line. In hyperbolic geometry these lines are mutually non-intersecting, while in Euclidean geometry they are mutually parallel.

Other results, such as the exterior angle theorem, clearly emphasize the difference between elliptic and the geometries that are extensions of absolute geometry.

Spherical geometry

Other geometries

Projective geometry

Affine geometry

Ordered geometry

Absolute geometry is an extension of ordered geometry, and thus, all theorems in ordered geometry hold in absolute geometry. The converse is not true. Absolute geometry assumes the first four of Euclid's Axioms (or their equivalents), to be contrasted with affine geometry, which does not assume Euclid's third and fourth axioms. Ordered geometry is a common foundation of both absolute and affine geometry.[80]

Finite geometry

See also

Notes

- ↑ Venema 2006, p. 17

- ↑ Wylie 1964, p. 8

- ↑ Greenberg 2007, p. 59

- ↑ In this context no distinction is made between different categories of theorems. Propositions, lemmas, corollaries, etc. are all treated the same.

- ↑ Venema 2006, p. 19

- ↑ Faber 1983, pp. 105 – 8

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Eves 1963, p. 19

- ↑ Eves 1963, p. 10

- ↑ Boyer (1991). "Euclid of Alexandria". A History of Mathematics. p. 101. "With the exception of the Sphere of Autolycus, surviving work by Euclid are the oldest Greek mathematical treatises extant; yet of what Euclid wrote more than half has been lost,"

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece (2006) by Nigel Guy Wilson, page 278. Published by Routledge Taylor and Francis Group. Quote:"Euclid's Elements subsequently became the basis of all mathematical education, not only in the Romand and Byzantine periods, but right down to the mid-20th century, and it could be argued that it is the most successful textbook ever written."

- ↑ Boyer (1991). "Euclid of Alexandria". A History of Mathematics. p. 100. "As teachers at the school he called a band of leading scholars, among whom was the author of the most fabulously successful mathematics textbook ever written – the Elements (Stoichia) of Euclid."

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Boyer (1991). "Euclid of Alexandria". A History of Mathematics. p. 119. "The Elements of Euclid not only was the earliest major Greek mathematical work to come down to us, but also the most influential textbook of all times. [...]The first printed versions of the Elements appeared at Venice in 1482, one of the very earliest of mathematical books to be set in type; it has been estimated that since then at least a thousand editions have been published. Perhaps no book other than the Bible can boast so many editions, and certainly no mathematical work has had an influence comparable with that of Euclid's Elements."

- ↑ The Historical Roots of Elementary Mathematics by Lucas Nicolaas Hendrik Bunt, Phillip S. Jones, Jack D. Bedient (1988), page 142. Dover publications. Quote:"the Elements became known to Western Europe via the Arabs and the Moors. There the Elements became the foundation of mathematical education. More than 1000 editions of the Elements are known. In all probability it is, next to the Bible, the most widely spread book in the civilization of the Western world."

- ↑ From the introduction by Amit Hagar to Euclid and His Modern Rivals by Lewis Carroll (2009, Barnes & Noble) pg. xxviii:

Geometry emerged as an indispensable part of the standard education of the English gentleman in the eighteenth century; by the Victorian period it was also becoming an important part of the education of artisans, children at Board Schools, colonial subjects and, to a rather lesser degree, women. ... The standard textbook for this purpose was none other than Euclid's The Elements.

- ↑ Euclid, book I, proposition 47

- ↑ Heath 1956, pp. 195 – 202 (vol 1)

- ↑ Venema 2006, p. 11

- ↑ Ball 1960, p. 55

- ↑ Wylie 1964, p. 39

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Faber 1983, p. 109

- ↑ Faber 1983, p. 113

- ↑ Faber 1983, p. 115

- ↑ Heath 1956, p. 62 (vol. I)

- ↑ Greenberg 2007, p. 57

- ↑ Heath 1956, p. 242 (vol. I)

- ↑ Heath 1956, p. 249 (vol. I)

- ↑ Eves 1963, p. 380

- ↑ Peano 1889

- ↑ Eves 1963, p. 382

- ↑ Eves 1963, p. 383

- ↑ Pieri did not attend since he had recently moved to Sicily, but he did have a paper of his read at the Congress of Philosophy.

- ↑ Hilbert 1950

- ↑ Hilbert 1990

- ↑ This is Hilbert's terminology. This statement is more familiarly known as Playfair's axiom.

- ↑ Eves 1963, p. 386

- ↑ Moore, E.H. (1902), "On the projective axioms of geometry", Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 3 (1): 142–158, doi:10.2307/1986321

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Eves 1963, p. 387

- ↑ Birkhoff, George David (1932), "A set of postulates for plane geometry", Annals of Mathematics 33 (2): 329–345, doi:10.2307/1968336

- ↑ Venema 2006, p. 400

- ↑ Venema 2006, pp. 400–1

- ↑ Halsted, G. B. (1904), Rational Geometry, New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 Eves 1963, p. 388

- ↑ among his several achievements, he is the cofounder (with Samuel Eilenberg) of Category theory.

- ↑ Mac Lane, Saunders (1959), "Metric postulates for plane geometry", American Mathematical Monthly 66 (7): 543–555, doi:10.2307/2309851

- ↑ Birkhoff, G.D.; Beatley, R. (1940), Basic Geometry, Chicago: Scott, Foresman and Company [Reprint of 3rd edition: American Mathematical Society, 2000. ISBN 978-0-8218-2101-5]

- ↑ Venema 2006, pp. 401–2

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Venema 2006, p. 55

- ↑ School Mathematics Study Group (SMSG) (1961), Geometry, Parts 1 and 2 (Student Text), New Haven and London: Yale University Press

- ↑ Moise, Edwin E.; Downs, Floyd L. (1991), Geometry, Reading, MA: Addison–Wesley

- ↑ Venema 2006, p. 403

- ↑ Venema 2006, pp. 403–4

- ↑ Venema 2006, pp. 405 – 7

- ↑ Forder, H.G. (1927), "The Foundations of Euclidean Geometry", Nature (New York: Cambridge University Press) 123 (3089): 44, doi:10.1038/123044a0, Bibcode: 1928Natur.123...44. (reprinted by Dover, 1958)

- ↑ Huntington, E.V. (1913), "A set of postulates for abstract geometry, expressed in terms of the simple relation of inclusion", Mathematische Annalen 73 (4): 522–559, doi:10.1007/bf01455955, https://zenodo.org/record/1428276

- ↑ Robinson, G. de B. (1946), The Foundations of Geometry, Mathematical Expositions No. 1 (2nd ed.), Toronto: University of Toronto Press

- ↑ Kline, Morris (1967), Mathematics for the Nonmathematician, New York: Dover, p. 474, ISBN 0-486-24823-2, https://archive.org/details/mathematicsforno00klin/page/474

- ↑ Greenberg 2007, p. 1

- ↑ while only two lines are postulated, it is easily shown that there must be an infinite number of such lines.

- ↑ Book I Proposition 27 of Euclid's Elements

- ↑ Felix Klein, Elementary Mathematics from an Advanced Standpoint: Geometry, Dover, 1948 (reprint of English translation of 3rd Edition, 1940. First edition in German, 1908) pg. 176

- ↑ F. Klein, Über die sogenannte nichteuklidische Geometrie, Mathematische Annalen, 4(1871).

- ↑ Florence P. Lewis (Jan 1920), "History of the Parallel Postulate", The American Mathematical Monthly (The American Mathematical Monthly, Vol. 27, No. 1) 27 (1): 16–23, doi:10.2307/2973238.

- ↑ In a letter of December 1818, Ferdinand Karl Schweikart (1780–1859) sketched a few insights into non-Euclidean geometry. The letter was forwarded to Gauss in 1819 by Gauss's former student Gerling. In his reply to Gerling, Gauss praised Schweikart and mentioned his own, earlier research into non-Euclidean geometry.

- ↑ In the letter to Wolfgang (Farkas) Bolyai of March 6, 1832 Gauss claims to have worked on the problem for thirty or thirty-five years (Faber 1983). In his 1824 letter to Taurinus (Faber 1983) he claimed that he had been working on the problem for over 30 years and provided enough detail to show that he actually had worked out the details. According to (Faber 1983) it wasn't until around 1813 that Gauss had come to accept the existence of a new geometry.

- ↑ Beltrami, Eugenio (1868) "Teoria fondamentale degli spazî di curvatura costante", Annali di Matematica Pura et Applicata, Series II 2:232–255.

- ↑ An appropriate example of logical equivalence is given by Playfair's axiom and Euclid I.30 (see Playfair's axiom#Transitivity of parallelism).

- ↑ For instance, Hilbert uses Playfair's axiom while Birkhoff uses the theorem about similar but not congruent triangles.

- ↑ attributions are due to Trudeau 1987, pp. 128–9

- ↑ Use a complete set of axioms for Euclidean geometry such as Hilbert's axioms or another modern equivalent (Faber 1983). Euclid's original set of axioms is ambiguous and not complete, it does not form a basis for Euclidean geometry.

- ↑ In "Appendix exhibiting the absolute science of space: independent of the truth or falsity of Euclid's Axiom XI (by no means previously decided)" (Faber 1983)

- ↑ Greenberg cites W. Prenowitz and M. Jordan (Greenberg, p. xvi) for having used the term neutral geometry to refer to that part of Euclidean geometry that does not depend on Euclid's parallel postulate. He says that the word absolute in absolute geometry misleadingly implies that all other geometries depend on it.

- ↑ Trudeau 1987, p. 44

- ↑ Absolute geometry is, in fact, the intersection of hyperbolic geometry and Euclidean geometry when these are regarded as sets of propositions.

- ↑ Faber 1983, p. 167

- ↑ Beltrami, Eugenio (1868), "Teoria fondamentale degli spazii di curvatura costante", Annali di Matematica Pura ed Applicata, Series II 2: 232–255, doi:10.1007/BF02419615, https://zenodo.org/record/2243105

- ↑ Greenberg 2007, pp. 541–4

- ↑ Visualize four points on a circle which in counter-clockwise order are A, B, C and D.

- ↑ This reenforces the futility of attempting to "fix" Euclid's axioms to obtain this geometry. Changes need to be made in the unstated assumptions of Euclid.

- ↑ Negative defect is called the excess, so this may also be phrased as– triangles have a positive excess in elliptic geometry.

- ↑ Coxeter, pgs. 175–176

References

- Ball, W.W. Rouse (1960). A Short Account of the History of Mathematics (4th ed. [Reprint. Original publication: London: Macmillan & Co., 1908] ed.). New York: Dover Publications. pp. 50–62. ISBN 0-486-20630-0. https://archive.org/details/shortaccountofhi0000ball/page/50.

- Beutelspacher, Albrecht; Rosenbaum, Ute (1998), Projective geometry: from foundations to applications, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-48364-3

- Eves, Howard (1963), A Survey of Geometry (Volume One), Boston: Allyn and Bacon

- Faber, Richard L. (1983), Foundations of Euclidean and Non-Euclidean Geometry, New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc., ISBN 0-8247-1748-1

- Greenberg, Marvin Jay (2007), Euclidean and Non-Euclidean Geometries/Development and History, 4th edition, San Francisco: W.H. Freeman, ISBN 978-0716799481

- Heath, Thomas L. (1956). The Thirteen Books of Euclid's Elements (2nd ed. [Facsimile. Original publication: Cambridge University Press, 1925] ed.). New York: Dover Publications. https://archive.org/details/thirteenbooksofe00eucl.

- (3 vols.): ISBN 0-486-60088-2 (vol. 1), ISBN 0-486-60089-0 (vol. 2), ISBN 0-486-60090-4 (vol. 3).

- Hilbert, David (1950), The Foundations of Geometry [Grundlagen der Geometrie], English translation by E.J. Townsend (2nd ed.), La Salle, IL: Open Court Publishing, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/17384/17384-pdf.pdf

- Hilbert, David (1990), Foundations of Geometry [Grundlagen der Geometrie], translated by Leo Unger from the 10th German edition (2nd English ed.), La Salle, IL: Open Court Publishing, ISBN 0-87548-164-7

- Moise, Edwin E. (1974), Elementary Geometry from an Advanced Standpoint (2nd ed.), Reading, MA: Addison–Wesley, ISBN 0-201-04793-4

- Peano, Giuseppe (1889), I principii di geometria: logicamente esposti, Turin: Fratres Bocca

- Russell, Bertrand (1897) An Essay on the Foundations of Geometry, via Internet Archive

- Trudeau, Richard J. (1987), The Non-Euclidean Revolution, Boston: Birkhauser, ISBN 0-8176-3311-1, https://archive.org/details/noneuclideanrevo0000trud

- Venema, Gerard A. (2006), Foundations of Geometry, Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13-143700-3

- Wylie, C.R. Jr. (1964), Foundations of Geometry, New York: McGraw–Hill

External links

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Moritz Pasch", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Pasch.html.

- A. Seidenberg (2008). "Pasch, Moritz". Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-2830903301.html.

- Moritz Pasch at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Giuseppe Peano", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Peano.html.

- Hubert Kennedy (2002). "Twelve articles on Giuseppe Peano". San Francisco: Peremptory Publications. http://hubertkennedy.angelfire.com/TwelveArticles.pdf. Collection of articles on life and mathematics of Peano (1960s to 1980s).

- Giuseppe Peano at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Mario Pieri", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Pieri.html.

- Hubert Kennedy. "Pieri, Mario". Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-2830903412.html.

- SMSG axioms

|

KSF

KSF