-

W. L. Bragg

-

C. G. Darwin

-

Peter Clapham

National Physical Laboratory (United Kingdom)

Topic: Organization

From HandWiki - Reading time: 14 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 14 min

| |

NPL's main entrance on Hampton Road | |

| Established | 1900 |

|---|---|

| Research type | Applied Physics |

Field of research | Metrology |

Chief Executive Officer | Peter Thompson |

| Staff | c. 1,000[1] |

| Address | Hampton Road, Teddington, TW11 0LW, England, UK |

| Location | [ ⚑ ] : 51°25′35″N 0°20′37″W / 51.42639°N 0.34361°W |

Operating agency | Department for Science, Innovation and Technology |

| Website | www |

The National Physical Laboratory (NPL) is the national measurement standards laboratory of the United Kingdom. It sets and maintains physical standards for British industry.

Founded in 1900, the NPL is one of the oldest metrology institutes in the world. Research and development work at the laboratory has contributed to the advancement of many disciplines of science, including the development of early computers in the late 1940s and 1950s, construction of the first accurate atomic clock in 1955, and the invention and pioneering implementation of packet switching in the 1960s, which is today one of the fundamental technologies of the Internet.[2][3][4] The former heads of NPL include many individuals who were pillars of the British scientific establishment.[5][6]

NPL is based at Bushy Park in Teddington, west London. It is managed under the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology and is one of the most extensive government laboratories in the United Kingdom.

History

Precursors

In the 19th century, the Kew Observatory was run by self-funded devotees of science. In the early 1850s, the observatory began charging fees for testing meteorological instruments and other scientific equipment. As universities in the United Kingdom created and expanded physics departments, the governing committee of the Observatory became increasingly dominated by paid university physicists in the last two decades of the nineteenth century. By this time, instrument-testing was the observatory's main role. Physicists sought the establishment of a state-funded scientific institution for testing electrical standards.[7]

Founding

The National Physical Laboratory was established in 1900 at Bushy House in Teddington on the site of the Kew Observatory. Its purpose was "for standardising and verifying instruments, for testing materials, and for the determination of physical constants".[8] The laboratory was run by the UK government, with members of staff being part of the civil service. It grew to fill a large selection of buildings on the Teddington site.[9]

Late 20th century

Administration of NPL was contracted out in 1995 under a Government Owned Contractor Operated (GOCO) model, with Serco winning the bid and all staff transferred to their employment. Under this regime, overhead costs halved, third-party revenues grew by 16% per annum, and the number of peer-reviewed research papers published doubled.[10][11]

NPL procured a large state-of-the-art laboratory under a Private Finance Initiative contract in 1998. The construction was undertaken by John Laing.[12]

21st century

The new laboratory building, which had been maintained by Serco, was transferred back to the DTI in 2004 after the private sector companies involved made losses of over £100m.[12]

It was decided in 2012 to change the operating model for NPL from 2014 onwards to include academic partners and to establish a postgraduate teaching institute on site.[13] The date of the changeover was later postponed for a year.[14] The candidates for lead academic partner were the Universities of Edinburgh, Southampton, Strathclyde and Surrey[15] with an alliance of the Universities of Strathclyde and Surrey chosen as preferred partners.[16]

Funding was announced in January 2013 for a new £25m Advanced Metrology Laboratory that will be built on the footprint of an existing unused building.[17][18]

The operation of the laboratory transferred back to the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (now the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy) on 1 January 2015.[19]

Notable researchers

Researchers who have worked at NPL include:[20] D. W. Dye who did important work in developing the technology of quartz clocks; the inventor Sir Barnes Wallis who did early development work on the "Bouncing Bomb" used in the "Dam Busters" wartime raids;[21] H. J. Gough, one of the pioneers of research into metal fatigue, who worked at NPL for 19 years from 1914 to 1938; and Sydney Goldstein and Sir James Lighthill who worked in NPL's aerodynamics division during World War II researching boundary layer theory and supersonic aerodynamics respectively.[22]

Alan Turing, known for his work at the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park during the Second World War to decipher German encrypted messages, worked at the National Physical Laboratory from 1945 to 1947.[23] He designed there the ACE (Automatic Computing Engine), which was one of the first designs for a stored-program computer. Dr Clifford Hodge also worked there and was engaged in research on semiconductors. Others who have spent time at NPL include Robert Watson-Watt, generally considered the inventor of radar, Oswald Kubaschewski, the father of computational materials thermodynamics and the numerical analyst James Wilkinson.[24]

Metallurgist Walter Rosenhain appointed the NPL's first female scientific staff members in 1915, Marie Laura Violet Gayler and Isabel Hadfield.[25]

Research

NPL research has contributed to physical science, materials science, computing, and bioscience. Applications have been found in ship design, aircraft development, radar, computer networking, and global positioning.[26]

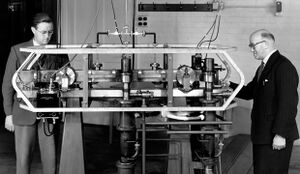

Atomic clocks

The first accurate atomic clock, a caesium standard based on a certain transition of the caesium-133 atom, was built by Louis Essen and Jack Parry in 1955 at NPL.[27][28] Calibration of the caesium standard atomic clock was carried out by the use of the astronomical time scale ephemeris time (ET).[29] This led to the internationally agreed definition of the latest SI second being based on atomic time.[30]

Computing

Early computers

NPL has undertaken computer research since the mid-1940s.[31] From 1945, Alan Turing led the design of the Automatic Computing Engine (ACE) computer. The ACE project was overambitious and floundered, leading to Turing's departure.[32] Donald Davies took the project over and concentrated on delivering the less ambitious Pilot ACE computer, which first worked in May 1950. Among those who worked on the project was American computer pioneer Harry Huskey. A commercial spin-off, DEUCE was manufactured by English Electric Computers and became one of the best-selling machines of the 1950s.[32]

Packet switching

Beginning in the mid-1960s, Donald Davies and his team at the NPL pioneered packet switching, now the dominant basis for data communications in computer networks worldwide.[33] Davies designed and proposed a national commercial data network in his 1965 Proposal for the Development of a National Communications Service for On-line Data Processing.[34] Subsequently, the NPL team (Davies, Derek Barber, Roger Scantlebury, Peter Wilkinson, Keith Bartlett, and Brian Aldous) were the first to implement packet switching in the local-area NPL network in 1969,[35][36] which operated until 1986. They carried out work to analyse and simulate the performance of packet-switched networks, including datagram networks. Their research and practice influenced the ARPANET in the United States, the forerunner of the Internet, and other researchers in the UK and Europe, including Louis Pouzin.[37][38][39][40]

NPL sponsors a gallery, opened in 2009, about the development of packet switching and "Technology of the Internet" at The National Museum of Computing.[41]

Internetworking

NPL internetworking research was led by Davies, Barber and Scantlebury, who were members of the International Networking Working Group (INWG).[42][43][44] Connecting heterogeneous computer networks creates a "basic dilemma" since a common host protocol would require restructuring the existing networks. NPL connected with the European Informatics Network (Barber directed the project and Scantlebury led the UK technical contribution)[45][46][47] by translating between two different host protocols; that is, using a gateway. Concurrently, the NPL connection to the Post Office Experimental Packet Switched Service used a common host protocol in both networks. NPL research confirmed establishing a common host protocol would be more reliable and efficient.[48] The EIN protocol helped to launch the proposed INWG standard.[49] Bob Kahn and Vint Cerf acknowledged Davies and Scantlebury in their 1974 paper "A Protocol for Packet Network Intercommunication".[50]

Scrapbook

Scrapbook was an information storage and retrieval system that went live in mid-1971. It included what would now be called word processing, e-mail and hypertext. In this it anticipated many elements of the World Wide Web. The project was managed by David Yates who said of it "We had a community of bright people that were interested in new things, they were good fodder for a system like Scrapbook" and "When we had more than one Scrapbook system, hyperlinks could go across the network without the user knowing what was happening".[51][52] It was decided that any commercial development of Scrapbook should be left to industry and it was licensed to Triad and then to BT who marketed it as Milepost and developed a transaction processor as an additional feature. Various implementations were marketed on DEC, IBM and ITL machines. All NPL implementations of Scrapbook were closed down in 1984.[53]

Secure communication

In the early 1990s, the NPL developed three formal specifications of the MAA: one in Z,[54] one in LOTOS,[55] and one in VDM.[56][57] The VDM specification became part of the 1992 revision of the International Standard 8731–2, and three implementations in C, Miranda, and Modula-2.[58]

Electromagnetics

A 2020 study by researchers from Queen Mary University of London and NPL successfully used microwaves to measure blood-based molecules known to be influenced by dehydration.[59]

Metrology

The National Physical Laboratory is involved with new developments in metrology, such as researching metrology for, and standardising, nanotechnology.[60] It is mainly based at the Teddington site, but also has a site in Huddersfield for dimensional metrology[61] and an underwater acoustics facility at Wraysbury Reservoir near Heathrow Airport.[62]

Directors of NPL

Directors of NPL include a number of notable individuals:[63]

- Sir Richard Tetley Glazebrook, 1900–1919

- Sir Joseph Ernest Petavel, 1919–1936

- Sir Frank Edward Smith, 1936–1937 (acting)

- Sir William Lawrence Bragg, 1937–1938

- Sir Charles Galton Darwin, 1938–1949

- Sir Edward Victor Appleton, 1941 (acting)

- Sir Edward Crisp Bullard, 1948–1955

- Dr Reginald Leslie Smith-Rose, 1955–1956 (acting)

- Sir Gordon Brims Black McIvor Sutherland, 1956–1964

- Dr John Vernon Dunworth, 1964–1977

- Dr Paul Dean, 1977–1990

- Dr Peter Clapham, 1990–1995

Managing Directors

- Dr John Rae, 1995–2000

- Dr Bob McGuiness, 2000–2005

- Steve McQuillan, 2005–2008

- Dr Martyn Sené, 2008–2009, 2015 (acting)

- Dr Brian Bowsher, 2009–2015

Chief Executive Officers

- Dr Peter Thompson, 2015–present[64]

NPL buildings

- NPL buildings

-

Bushy House

-

The Darwin building

-

New building with preserved gates from the original entrance on Queen's Road

-

Part of the new building

-

Painting of the laboratory by Lee Campbell, resident artist there in 2009

-

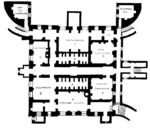

Ground floor plan of Bushy House in 1901/1902

-

Basement plan of Bushy House in 1901/1902

See also

- Outline of metrology and measurement

- List of UK government scientific research institutes

- National Institute of Standards and Technology in the United States

- National Physical Laboratory of India

- VAMAS

References

- ↑ "About us" (in en). https://www.npl.co.uk/about-us.

- ↑ Needham, Roger M. (2002). "Donald Watts Davies, C.B.E. 7 June 1924 – 28 May 2000" (in en). Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society 48: 87–96. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2002.0006. ISSN 0080-4606. "This was the start of 10 years of pioneering work at the NPL in packet switching. ... At that lecture he first became aware that Paul Baran, of the RAND Corporation, had proposed a similar system in the context of military communication. His report was not as detailed as Davies’s design and had not been acted on.".

- ↑ Feder, Barnaby J. (2000-06-04). "Donald W. Davies, 75, Dies; Helped Refine Data Networks" (in en-US). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/2000/06/04/business/donald-w-davies-75-dies-helped-refine-data-networks.html. "Donald W. Davies, who proposed a method for transmitting data that made the Internet possible"

- ↑ Harris, Trevor, Who is the Father of the Internet? The case for Donald Watts Davies, https://www.academia.edu/378261, retrieved 10 July 2013

- ↑ Naughton, John (2015-09-24) (in en). A Brief History of the Future. Orion. ISBN 978-1-4746-0277-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=bbonCgAAQBAJ&q=English+outfit. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ↑ Russell, Andrew L. (2014-04-28) (in en). Open Standards and the Digital Age: History, Ideology, and Networks. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-91661-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=OVpzAwAAQBAJ&q=NPL. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ↑ Macdonald, Lee T. (2018-11-26). "University physicists and the origins of the National Physical Laboratory, 1830–1900" (in en). History of Science 59 (1): 73–92. doi:10.1177/0073275318811445. PMID 30474405. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0073275318811445. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ↑ "history". National Physical Laboratory. https://www.npl.co.uk/history.

- ↑ "Development of the NPL Site 1900-1970.pdf". 2013. http://www.npl.co.uk/upload/pdf/Development%20of%20the%20NPL%20Site%201900-1970.pdf.

- ↑ Labs under the microscope – Ethos . Ethosjournal.com (2 February 2012). Retrieved on 12 April 2014.

- ↑ Committee, Great Britain: Parliament: House of Commons: Science and Technology; Technology, Great Britain Parliament House of Commons Select Committee on Science and (2006-08-04) (in en). Identity Card Technologies: Scientific Advice, Risk and Evidence; Sixth Report of Session 2005-06; Report, Together with Formal Minutes, Oral and Written Evidence. The Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0-215-03047-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=ykhpbYM0xMoC&pg=PA109.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "The Termination of the PFI Contract for the National Physical Laboratory |National Audit Office". nao.org.uk. 2013. https://www.nao.org.uk/report/the-termination-of-the-pfi-contract-for-the-national-physical-laboratory/.

- ↑ "Microsoft Word - Briefing document 26 March 2013_final - establishing-a-new-partnership-for-the-npl-briefing-note.pdf". 2013. http://www.bis.gov.uk/assets/nmo/docs/nms/future-operation-of-npl/establishing-a-new-partnership-for-the-npl-briefing-note.pdf.

- ↑ Escape, The. "Serco" (in en). https://www.serco.com/uk/media-and-news/2014/national-physical-laboratory-contract-extension.

- ↑ "Future operation of the National Physical Laboratory | National Measurement System | BIS". bis.gov.uk. 2013. http://www.bis.gov.uk/nmo/national-measurement-system/future-operation-of-npl.

- ↑ "Press Release – Universities of Surrey and Strathclyde selected as strategic partners in the future operation of the National Physical Laboratory". NPL. 10 July 2014. pp. 5. http://www.npl.co.uk/upload/pdf/20140710-npl-future-op-press-release.pdf.

- ↑ Willetts, David (2013). "Announcement of £25 million Advanced Metrology Laboratory at NPL". bis.gov.uk (Press release). Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- ↑ "National Physical Laboratory, Hampton Road, Teddington, Middlesex, United Kingdom, TW11 0LW - aml-letter-july2013.pdf". 2013. http://www.npl.co.uk/upload/pdf/aml-letter-july2013.pdf.

- ↑ "Future operation of the National Physical Laboratory (NPL). Retrieved 24 March 2015". https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/future-operation-of-the-national-physical-laboratory-npl.

- ↑ "Notable Individuals". http://www.npl.co.uk/about/history/notable-individuals/.

- ↑ Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society

- ↑ "Professor Sir James Lighthill FRS". Imperial College London. https://www.imperial.ac.uk/fluids-cdt/about/lighthill-lectures/james-lighthill/.

- ↑ Copeland, B. Jack (2006). Colossus: The secrets of Bletchley Park's code-breaking computers. Oxford University Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-19-284055-4.

- ↑ "James (Jim) Hardy Wilkinson". IEEE Computer Society. http://history.computer.org/pioneers/wilkinson.html.

- ↑ Murphy, A. J. (1976). "Marie Laura Violet Gayler" (in en). Nature 263 (5577): 535–536. doi:10.1038/263535b0. ISSN 1476-4687. Bibcode: 1976Natur.263..535M.

- ↑ "Research". http://www.npl.co.uk/about/history/research/.

- ↑ Essen, L.; Parry, J. V. L. (1955). "An Atomic Standard of Frequency and Time Interval: A Cæsium Resonator". Nature 176 (4476): 280–282. doi:10.1038/176280a0. Bibcode: 1955Natur.176..280E.

- ↑ "60 years of the Atomic Clock". http://www.npl.co.uk/60-years-of-the-atomic-clock/.

- ↑ Markowitz, W; Hall, R G; Essen, L; Parry, J V L (1958). "Frequency of cesium in terms of ephemeris time". Physical Review Letters 1 (3): 105–107. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.1.105. Bibcode: 1958PhRvL...1..105M.

- ↑ "What Is International Atomic Time (TAI)?". Time and Date. https://www.timeanddate.com/time/international-atomic-time.html.

- ↑ "History of NPL Computing". http://www.npl.co.uk/science-technology/mathematics-modelling-and-simulation/history-of-computing/.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Campbell-Kelly, Martin (Autumn 2008). "Pioneer Profiles: Donald Davies". Computer Resurrection (44). ISSN 0958-7403. http://www.computerconservationsociety.org/resurrection/res44.htm. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ↑ Smith, Ed; Miller, Chris; Norton, Jim (2017). "Packet Switching: The first steps on the road to the information society". https://www.npl.co.uk/getattachment/about-us/History/Famous-faces/Donald-Davies/UK-role-in-Packet-Switching-(1).pdf.aspx?lang=en-GB.

- ↑ Davies, D. W. (1966), Proposal for a Digital Communication Network, National Physical Laboratory, http://www.dcs.gla.ac.uk/~wpc/grcs/Davies05.pdf, retrieved 3 October 2017

- ↑ John S, Quarterman; Josiah C, Hoskins (1986). "Notable computer networks" (in EN). Communications of the ACM 29 (10): 932–971. doi:10.1145/6617.6618. "The first packet-switching network was implemented at the National Physical Laboratories in the United Kingdom. It was quickly followed by the ARPANET in 1969.".

- ↑ Haughney Dare-Bryan, Christine (June 22, 2023). Computer Freaks (Podcast). Chapter Two: In the Air. Inc. Magazine. 35:55 minutes in.

Leonard Kleinrock: Donald Davies ... did make a single node packet switch before ARPA did

- ↑ Gillies, James; Cailliau, Robert (2000). How the Web was Born: The Story of the World Wide Web. Oxford University Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0192862075. https://archive.org/details/howwebwasbornsto00gill.

- ↑ Isaacson, Walter (2014). The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution. Simon & Schuster. p. 237. ISBN 9781476708690. https://books.google.com/books?id=4V9koAEACAAJ&pg=PA237. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ↑ Hempstead, C.; Worthington, W. (2005). Encyclopedia of 20th-Century Technology. Routledge. ISBN 9781135455514. https://books.google.com/books?id=2ZCNAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA574. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ↑ Stewart, Bill (7 January 2000). "UK National Physical Laboratory (NPL) & Donald Davies". Living Internet. http://www.livinginternet.com/i/ii_npl.htm.

- ↑ "Technology of the Internet". The National Museum of Computing. https://www.tnmoc.org/npl-gallery.

- ↑ McKenzie, Alexander (2011). "INWG and the Conception of the Internet: An Eyewitness Account". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 33 (1): 66–71. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2011.9. ISSN 1934-1547.

- ↑ Scantlebury, Roger (25 June 2013). "Internet pioneers airbrushed from history". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2013/jun/25/internet-pioneers-airbrushed-from-history.

- ↑ "How we nearly invented the internet in the UK". New Scientist. 8 January 2020. https://www.newscientist.com/letter/mg24532640-100-how-we-nearly-invented-the-internet-in-the-uk/.

- ↑ A, BarberD L. (1975-07-01). "Cost project 11" (in EN). ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review 5 (3): 12–15. doi:10.1145/1015667.1015669.

- ↑ Stokes, A. V. (23 May 2014). Communications Standards: State of the Art Report 14:3. ISBN 9781483160931. https://books.google.com/books?id=3EaeBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA203. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ↑ "EIN (European Informatics Network) – CHM Revolution". https://www.computerhistory.org/revolution/networking/19/375/2062.

- ↑ Abbate, Janet (2000) (in en). Inventing the Internet. MIT Press. pp. 125. ISBN 978-0-262-51115-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=E2BdY6WQo4AC&pg=PA125. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ↑ Hardy, Daniel; Malleus, Guy (2002) (in en). Networks: Internet, Telephony, Multimedia: Convergences and Complementarities. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 505. ISBN 978-3-540-00559-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=dRhHPINWo2AC&pg=PT526. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ↑ Cerf, V.; Kahn, R. (1974). "A Protocol for Packet Network Intercommunication". IEEE Transactions on Communications 22 (5): 637–648. doi:10.1109/TCOM.1974.1092259. ISSN 1558-0857. https://www.cs.princeton.edu/courses/archive/fall06/cos561/papers/cerf74.pdf. "The authors wish to thank a number of colleagues for helpful comments during early discussions of international network protocols, especially R. Metcalfe, R. Scantlebury, D. Walden, and H. Zimmerman; D. Davies and L. Pouzin who constructively commented on the fragmentation and accounting issues; and S. Crocker who commented on the creation and destruction of associations.".

- ↑ Ward, Mark (5 February 2010), Alan Turing and the Ace computer, BBC News, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/technology/8498826.stm, retrieved 17 February 2021

- ↑ David Yates talks about 'Scrapbook'. National Physical Laboratory via YouTube. 10 December 2009. Archived from the original on 2021-12-12. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ↑ Scrapbook and the umbrella (groupware from the 70's), Retro Computing Forum, 11 February 2021, https://retrocomputingforum.com/t/scrapbook-and-the-umbrella-groupware-from-the-70s/1781, retrieved 18 February 2021 which cites Yates, David M. (1997), Turing's Legacy: A History of Computing at the National Physical Laboratory 1945–1995, Science Museum, ISBN 978-0901805942

- ↑ Lai, M. K. F. (1991). A Formal Interpretation of the MAA Standard in Z (NPL Report DITC 184/91). Teddington, Middlesex, UK.

- ↑ Munster, Harold B. (1991). LOTOS Specification of the MAA Standard, with an Evaluation of LOTOS (NPL Report DITC 191/91). Teddington, Middlesex, UK. ftp://ftp.inrialpes.fr/pub/vasy/publications/others/Munster-91-a.pdf.

- ↑ Parkin, Graeme I.; O’Neill, G. (1990). Specification of the MAA Standard in VDM (NPL Report DITC 160/90).

- ↑ Parkin, Graeme I.; O’Neill, G. (1991). "Specification of the MAA Standard in VDM". Formal Software Development – Proceedings (Volume 1) of the 4th International Symposium of VDM Europe (VDM’91), Noordwijkerhout, The Netherlands. 551. Springer. pp. 526–544. doi:10.1007/3-540-54834-3_31.

- ↑ Lampard, R. P. (1991). An Implementation of MAA from a VDM Specification (NPL Technical Memorandum DITC 50/91). Teddington, Middlesex, UK.

- ↑ Researchers use microwaves to measure signs of dehydration, 2020, https://www.qmul.ac.uk/media/news/2020/se/researchers-use-microwaves-to-measure-signs-of-dehydration.html, retrieved 8 March 2021

- ↑ Minelli, C. & Clifford, C.A. (2012). "The role of metrology and the UK National Physical Laboratory in Nanotechnology". Nanotechnology Perceptions 8: 59–75.

- ↑ "Dimensional Specialist Inspection and Measurement Services : Measurement Services : Commercial Services : National Physical Laboratory". npl.co.uk. 2013. http://www.npl.co.uk/huddersfield.

- ↑ "Calibration and characterisation of sonar transducers and systems : Products & Services : Underwater Acoustics : Acoustics : Science + Technology : National Physical Laboratory". npl.co.uk. 2013. http://www.npl.co.uk/acoustics/underwater-acoustics/products-and-services/calibration-and-characterisation-of-sonar-transducers-and-systems.

- ↑ "Directors" (in en). http://www.npl.co.uk/about/history/directors/.

- ↑ "New CEO for National Physical Laboratory : News : News + Events : National Physical Laboratory". npl.co.uk. 2015. http://www.npl.co.uk/news/new-ceo-for-national-physical-laboratory.

Further reading

- Campbell-Kelly, Martin (1987). "Data Communications at the National Physical Laboratory (1965-1975)". Annals of the History of Computing 9 (3/4): 221–247. doi:10.1109/MAHC.1987.10023. ISSN 0164-1239. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/4640566.

- Claxton, J K (1983). "The National Physical Laboratory – A History" (in en). Physics Bulletin 34 (9): 395. doi:10.1088/0031-9112/34/9/029. ISSN 0031-9112.

- Macdonald, Lee T. (2018). "University physicists and the origins of the National Physical Laboratory, 1830–1900" (in en). History of Science 59 (1): 73–92. doi:10.1177/0073275318811445. ISSN 0073-2753. PMID 30474405.

- Moseley, Russell (1978). "The Origins and Early Years of the National Physical Laboratory: A Chapter in the Pre-history of British Science Policy". Minerva 16 (2): 222–250. doi:10.1007/BF01096015. ISSN 0026-4695.

- Yates, David M. (1997) (in en). Turing's Legacy: A History of Computing at the National Physical Laboratory 1945-1995. National Museum of Science and Industry. ISBN 978-0-901805-94-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=ToMfAQAAIAAJ.

- Vigoureux, P. (1988). "Electric units at the National Physical Laboratory, 1900-50". Papers Presented at the Sixteenth I.E.E. Week-End Meeting on the History of Electrical Engineering: 9–12. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/206273.

External links

- Official website

- The birth of the Internet in the UK Google video featuring Roger Scantlebury, Peter Wilkinson, Peter Kirstein and Vint Cerf, 2013

- NPL Video Podcast

- Second Health in Second Life

- NMS Home Page

- NPL YouTube channel

- NPL Sports and Social Club

- [1]

- The National Physical Laboratory apprentices[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- Benjamin Stone MP & the NPL – UK Parliament Living Heritage

|

KSF

KSF