University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa

Topic: Organization

From HandWiki - Reading time: 20 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 20 min

| |

Former name | College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts of the Territory of Hawaiʻi (1907–1912) College of Hawaiʻi (1912–1919) University of Hawaiʻi (1919–1972) |

|---|---|

| Motto | Maluna aʻe o nā lāhui āpau ke ola ke kānaka (Hawaiian)[1] On seal: Mālamalama (Hawaiian) |

Motto in English | "Above all nations is humanity" On seal: "Enlightenment[2]" |

| Type | Public land-grant research university |

| Established | March 23, 1907 |

Parent institution | University of Hawaiʻi |

Academic affiliations |

|

| Endowment | $341.7 million (system-wide) (2020)[3] |

| Budget | $1.1 billion (2019)[4] |

| President | David Lassner |

| Provost | Michael Bruno |

| Students | 19,098 (Fall 2021)[5] |

| Undergraduates | 14,120[5] |

| Postgraduates | 4,978[5] |

| Location | Honolulu , Hawaii , United States [ ⚑ ] : 21°17′49″N 157°49′01″W / 21.297°N 157.817°W |

| Campus | Large city |

| Other campuses[6] | |

| Newspaper | Ka Leo O Hawaiʻi |

| |u}}rs | Green and white[7][8] |

| Nickname | Rainbow Warriors & Rainbow Wāhine |

Sporting affiliations |

|

| Website | manoa |

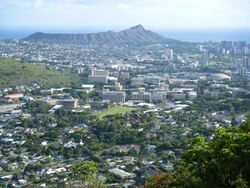

The University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa[lower-alpha 1] (University of Hawaii–Mānoa, UH Mānoa, Hawaiʻi, or simply UH) is a public land-grant research university in Mānoa, a neighborhood of Honolulu, Hawaii.[9][10] It is the flagship campus of the University of Hawaiʻi system and houses the main offices of the system.[11] Most of the campus occupies the eastern half of the mouth of Mānoa Valley, with the John A. Burns School of Medicine located adjacent to the Kakaʻako Waterfront Park.

UH offers over 200 degree programs across 17 colleges and schools. It is accredited by the WASC Senior College and University Commission and governed by the Hawaii State Legislature and a semi-autonomous board of regents. It also a member of the Association of Pacific Rim Universities.

Mānoa is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity".[12] It is a land-grant university that also participates in the sea-grant, space-grant, and sun-grant research consortia; it is one of only four such universities in the country (Oregon State University, Cornell University and Pennsylvania State University are the others).

Notable UH alumni include Patsy T. Mink, Robert Ballard, Richard Parsons, and the parents of Barack Obama – Barack Obama Sr. and Stanley Ann Dunham. Forty-four percent of Hawaii's state senators and 51 percent of its state representatives are UH graduates.[13]

History

Founding

The University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa was founded in 1907 as a land-grant college of agriculture and mechanical arts establishing "the College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts of the Territory of Hawaiʻi and to Provide for the Government and Support Thereof".[14] The bill Maui Senator William J. Huelani Coelho through the initiatives of Native Hawaiian legislators, a newspaper editor, petition of an Asian American bank cashier, and a president of Cornell University,[15] was introduced into the Territorial Legislature March 1, 1907 as Act 24, and signed into law March 25, 1907 by Governor George Carter, which officially established the College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts of the Territory of Hawaiʻi under a five-member Board of Regents[15] on the corner of Beretania and Victoria streets (now the location of the Honolulu Museum of Art School).[14] Regular classes began on September 14, 1908, with John Gilmore as the university's first president.

In September 1912 it moved to its present location in Mānoa Valley on 90 acres of land that had been cobbled together from leased and private lands and was renamed the College of Hawaii.[14] William Kwai Fong Yap, an cashier at Bank of Hawaii, and a group of citizens petitioned the Hawaii Territorial Legislature six years later for university status which led to another renaming finally to the University of Hawaiʻi on April 30, 1919, with the addition of the College of Arts and Sciences and College of Applied Science.[16][15]

In the years following, the university expanded to include more than 300 acres. In 1931 the Territorial Normal School was absorbed into the university, becoming Teacher's College,[16] now the College of Education.

20th century

The university continued its growth throughout the 1930s and 1940s increasing from 232 to 402 acres. The number of buildings grew from 4 to 17. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, classes were suspended for two months while the Corps of Engineers occupied much of the campus, including the Teacher's College, for various purposes. The university's ROTC program was put into active duty, which made the campus resemble a military school. When classes resumed on February 11, 1942, about half of the student and faculty body left to enter the war or military service. Students, who returned to campus, found classes cancelled due to lack of faculty and were required to carry gas masks to classes and bomb shelters were kept at a ready.[16] Once the war was over, student enrollment grew faster than the university had faculty and space for.

In 1947, the university opened an extension center in Hilo on Hawaiʻi Island in the old Hilo Boarding School. In 1951, Hilo Center was designated the University of Hawaii Hilo Branch[16] before its reorganization by an act of the Hawaiʻi State Legislature in 1970.[17]

By the 1950s, enrollment increased to more than 5,000 students, and the university had expanded to include a Graduate Division, College of Education, College of Engineering, College of Business Administration, College of Tropical Agriculture, and College of Arts and Sciences.[17]

When Hawaiʻi was granted statehood in 1959, the university became a constitutional agency rather than a legislative agency with the Board of Regents having oversight over the university. Enrollment continued to grow to 19,000 at the university through the 1960s and the campus became nationally recognized in research and graduate education.[17]

In 1965, the state legislature created a system of community colleges and placed it within the university at the recommendations of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare's report on higher education in Hawaii and UH President Thomas H. Hamilton.[15] By the end of the 1960s, the University of Hawaiʻi was very different from what it had since its beginning. It had become larger and with the addition of the community colleges, a broad range of activities extending from vocational education to community college education, which were all advanced through research and postdoctoral training.[17]

The university was renamed the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa to distinguish it from other campuses in the University of Hawaiʻi System in 1972.

Organization and administration

The University of Hawaiʻi is governed by an 11-member board of regents who are nominated by the Regents Candidate Advisory Council, appointed by the governor, and appointed by the State of Hawaiʻi legislature. The board also appoints the University of Hawaiʻi president, who also serves as the chief executive of the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

Presidents and chancellors

With the exception of the university's first semester, there has always been either a president, interim president, or chancellor. From 1907 to 1965, before the Hawaiʻi State Legislature created the University of Hawaiʻi System, which incorporated the technical and community colleges into the university, the president's role expanded to include oversight of all system campuses, with chancellors taking responsibility for individual campuses. As a result, the president has filled the role of chancellor at the university in addition to serving as president of the University of Hawaiʻi System.[18] The chancellor's position was created in 1974 and would be abolished in 1984, with Albert J. Simone becoming acting president on June 1, 1984.[17]

In 2001, the position of chancellor was recreated[19] by UH System president Evan Dobelle over conflict of interest concerns. It was again abolished in April 2019.[20]

Presidents

- 1907–1908: Willis T. Pope (acting)

- 1908–1913: John W. Gilmore

- 1913–1914: John Donaghho (acting)

- 1914–1927: Arthur L. Dean

- 1927–1941: David L. Crawford

- 1941–1942: Arthur R. Keller (acting)

- 1942–1955: Gregg M. Sinclair

- 1955–1957: Paul S. Bachman

- 1957–1958: Willard Wilson (acting)

- 1958–1963: Laurence H. Snyder

- 1963–1968: Thomas H. Hamilton

- 1968–1969: Robert W. Hiatt (acting)

- 1969: Richard S. Takasaki (acting)

- 1969–1974: Harlan Cleveland

- 1974–1984: See list of chancellors below

- 1984–1992: Albert J. Simone

- 1992–1993: Paul C. Yuen (acting)

- 1993–2001: Kenneth P. Mortimer

- 2001–2017: See list of chancellors below

- 2017–present: David Lassner

Chancellors

- 2001–2002: Deane Neubauer (interim)

- 2002–2005: Peter Englert

- 2005–2007: Denise Konan (interim)

- 2007–2012: Virginia Hinshaw

- 2012–2014: Tom Apple

- 2014–2017: Robert Bley-Vroman (interim)

Academics

UH Mānoa, the flagship campus of the University of Hawaiʻi System, is a four-year research university consisting of 17 schools and colleges. In addition to undergraduate and graduate degrees in the School of Architecture, School of Earth Science and Technology, the College of Arts, Languages, and Letters, the Shidler College of Business, the College of Education, and the College of Engineering, the university also maintains professional schools in law and medicine.

Together, the colleges and schools of the university offer bachelor's degrees in 93 fields of study, master's degrees in 84 fields, doctoral degrees in 51 fields, first professional degrees in five fields, post-baccalaureate degrees in three fields, 28 undergraduate certification programs, and 29 graduate certification programs.

College of Tropical Agriculture & Human Resources

Originally called the College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts of the Territory of Hawaiʻi and formerly the College of Applied Sciences, the College of Tropical Agriculture & Human Resources (CTAHR) is the founding college of the university. Programs of the college focuses on tropical agriculture, food science and human nutrition, textiles and clothing, and Human Resources.

College of Education

The college was established as the Honolulu Training School in 1895 to prepare and train teachers and then Territorial Normal and Training School after Hawaiʻi became a territory in 1905.[21] As the school outgrew its location on the Punchbowl side of Honolulu, a new campus was to be constructed on the corner of University Avenue and Metcalf Street. The first two buildings constructed by the Territorial Department of Public instruction became known as Wist Hall and Wist Annex 1.[22] The normal school was eventually merged into the University of Hawaiʻi in 1931 as the Teacher's College. In 1959, the name was changed to the College of Education.

College of Arts, Languages & Letters

The College of Arts, Languages, and Letters (CALL) is the newest and largest college at the university. It was created following the dissolution of the College of Arts and Science and the merger of the Colleges of Arts and Humanities, Languages, Linguistics, and Literature (LLL) and the School of Pacific and Asian Studies. The college's core focus is the study of arts, humanities, and languages with a particular focus on Hawaiʻi, the Pacific, and Asia Studies.[23]

Shidler College of Business

The College of Business Administration was established in 1949 with programs in accounting, finance, real estate, industrial relations, and marketing. The college was renamed the Shidler College of Business on September 6, 2006, after real-estate executive Jay Shidler, an alumnus of the college, who donated $25 million to the college.[24]

Nancy Atmospera-Walch School of Nursing

The School of Nursing was established in 1951, even though courses in nursing had been offered since 1932 with a partnership with Queen's Hospital School of Nursing.[15]

Honors program

The UH Mānoa offers an Honors Program to provide additional resources for students preparing to apply to professional school programs.[25] Students complete core curriculum courses for their degrees in the Honors Program, maintain at least a cumulative 3.2 grade-point average in all courses, and complete a senior thesis project.[26]

Library

The University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library, which provides access to 3.4 million volumes, 50,000 journals, and thousands of digitized documents, is one of the largest academic research libraries in the United States, ranking 86th in parent institution investment among 113 North American members of the Association of Research Libraries.[27]

Rankings

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The National Science Foundation ranked UH Mānoa 45th among 395 public universities for Research and Development (R&D) expenditures in fiscal year 2014.[39]

According to U.S. News & World Report's rankings for 2021, UH Mānoa was tied at 170th overall and 159th for "Best Value" among national universities; tied at 83rd among public universities; and tied at 145th for its undergraduate engineering program among schools that confer doctorates.[40]

Distance learning

The university offers over 50 distance learning courses, using technology to replace either all or a portion of class instruction. Students interact with their instructors and peers from different locations to further develop their education.[41]

Research

With extramural grants and contracts of $436 million in 2012, research at UH Mānoa relates to Hawaii's physical landscape, its people and their heritage. The geography facilitates advances in marine biology, oceanography, underwater robotic technology, astronomy, geology and geophysics, agriculture, aquaculture and tropical medicine. Its heritage, the people and its close ties to the Asian and Pacific region create a favorable environment for study and research in the arts, genetics, intercultural relations, linguistics, religion and philosophy.[42]

According to the National Science Foundation, UH Mānoa spent $276 million on research and development in 2018, ranking it 84th in the nation.[39] Extramural funding increased from $368 million in FY 2008 to nearly $436 million in FY 2012. Research grants increased from $278 million in FY 2008 to $317 million in FY 2012. Nonresearch awards totaled $119 million in FY 2012. Overall, extramural funding increased by 18%.[42][43]

For the period of July 1, 2012 to June 20, 2013, the School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST) received the largest amount of extramural funding among the Mānoa units at $92 million. SOEST was followed by the medical school at $57 million, the College of Natural Sciences and the University of Hawaiʻi Cancer Center at $24 million, the Institute for Astronomy at $22 million, CTARH at $18 million, and the College of Social Sciences and the College of Education at $16 million.[44]

Across the UH system, the majority of research funding comes from the Department of Health and Human Services, the Department of Defense, the Department of Education, the National Science Foundation, the Department of Commerce, and the National Aeronautics Space Administration (NASA). Local funding comes from Hawaii government agencies, non-profit organizations, health organizations and business and other interests.[44]

The $150-million medical complex in Kakaʻako opened in the spring of 2005. The facility houses a biomedical research and education center that attracts significant federal funding and private sector investment in biotechnology and cancer research and development.[citation needed]

Research (broadly conceived) is expected of every faculty member at UH Mānoa. Also, according to the Carnegie Foundation, UH Mānoa is an RU/VH (very high research activity) level research university.[45]

In 2013, UH Mānoa was elected to membership in the Association of Pacific Rim Universities, the leading consortium of research universities for the region. APRU represents 45 premier research universities—with a collective 2 million students and 120,000 faculty members—from 16 economies.[46]

Cancer Center

The University of Hawaiʻi Cancer Center part of the Hawaiʻi at Mānoa with the facility completed in 2013 at Kakaʻako in Honolulu.[47] It is designated as cancer center by the National Cancer Institute and represents Hawaiʻi and the Pacific. It was founded in 1971 and was named the Cancer Research Center of Hawaiʻi before 2011.[48]

Demographics

| Race and ethnicity[49] | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Asian | 36% | ||

| Other[lower-alpha 2] | 26% | ||

| White | 18% | ||

| Hispanic | 13% | ||

| Foreign national | 3% | ||

| Pacific Islander | 2% | ||

| Black | 1% | ||

| Economic diversity | |||

| Low-income[lower-alpha 3] | 26% | ||

| Affluent[lower-alpha 4] | 74% | ||

UH is the fourth most diverse university in the U.S.[13] According to the 2010 report of the Institutional Research Office, a plurality of students at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa are Caucasian, making up a quarter of the student body. The next largest groups were Japanese Americans (13%), native or part native Hawaiians (13%), Filipino Americans (8%), Chinese Americans (7%) and mixed race (12%). Pacific Islanders and other ethnic groups make up the balance (22%).

Student life

Student housing

All UH Mānoa residence halls are coeducational. These include the Hale Aloha Complex, Johnson Hall, Hale Laulima, and Hale Kahawai. Suite-style residence halls include Frear Hall and Gateway House. First year undergraduates who choose to live on campus live in the traditional residence halls.[50]

Two apartment-style complexes are Hale Noelani and Hale Wainani. Hale Noelani consists of five three-story buildings and Hale Wainani has two high rise buildings (one 14-story and one 13-story) and two low-rise buildings. Second-year undergraduates and above are permitted to live in Hale Noelani and Hale Wainani.[50]

The university reserves some low-rise units for graduate students and families.[51]

Charles H. Atherton YMCA

The University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa and the YMCA of Honolulu has enjoyed a close and robust partnership since the university's founding.[52] Beginning informally in 1908, the YMCA held bible classes and discussions at the University of Hawaiʻi, when it was the College of Hawaiʻi. In 1912, the YMCA of Honolulu followed the college to Mānoa valley and continued its work in Hawaiʻi Hall. In 1922, the relationship was formalized and it was one of the largest and most active groups on the university's campus, including hosting events for high school and incoming students.[53][52]

In 1932, through funding by the Atherton family, the YMCA moved across the street to a three-story cement building on University Avenue. The building, called the Charles H. Atherton House or the "Pink Building", in addition to being the center for YMCA activities, also served as student housing and dining hall. In 1995, the YMCA purchased the Mary Atherton House next door to provide additional residential and activity space.

In 2017, the Atherton building was sold to the university and University of Hawaiʻi Foundation.[53][52] Today, its main offices are located in the Queen Lili'uokalani Center for Student Services building on the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, where they continue serve UH students and families throughout Hawaiʻi.

The Atherton building has since been closed and renovations began July 2021 to turn the Pink Building into student housing and an innovation center.[54]

Associated Students of the University of Hawaiʻi

The Associated Students of the University of Hawaiʻi at Manoa (ASUH) is the undergraduate student government representing the 10,000+ full-time, classified, undergraduate students at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. ASUH was founded in 1910 as the Associated Students of Hawaiʻi[15] and was chartered by the University of Hawaiʻi Board of Regents in 1912.

Off-campus

- The Lyon Arboretum is the only tropical arboretum belonging to any US University. The Arboretum, located in Mānoa Valley, was established in 1918 by the Hawaiian Sugar Planters' Association to demonstrate watershed restoration and test tree species for reforestation, as well as to collect living plants of economic value. In 1953, it became part of the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. Its over 15,000 accessions focus primarily on the monocot families of palms, gingers, heliconias, bromeliads and aroids.

- The Waikiki Aquarium, founded in 1904, is the third-oldest public aquarium in the United States. A part of the University of Hawaiʻi since 1919, the Aquarium is located next to a living reef on the Waikiki shoreline.

Athletics

The University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa competes in NCAA Division I, the only Hawaii school to do so. It competes in the Mountain West Conference for football only and the Big West Conference for most other sports.[55] UH competes in the Mountain Pacific Sports Federation in men's and women's swimming and diving, and indoor track and field while the coed and women's sailing teams are members of the Pacific Coast Collegiate Sailing Conference.

Men's teams are known as Rainbow Warriors, and women's teams are called Rainbow Wahine. "Wahine" means "woman" in Hawaiian.[56] They are most notable for men's and women's basketball, volleyball, baseball, and football programs. The university won the 2004 Intercollegiate Sailing Association National Championships. The women's volleyball program won NCAA championships in 1982, 1983 and 1987. The men's volleyball won an NCAA championship in 2021.[57] The men's volleyball team had previously won an NCAA championship title game in 2002, but the title was later vacated due to violations.

The principal sports venues are Clarence T. C. Ching Athletics Complex, Stan Sheriff Center, Les Murakami Stadium, Rainbow Wahine Softball Stadium, and the Duke Kahanamoku Aquatic Complex.

The university's athletic budget in FY 2008–2009 was $29.6 million.[58]

Notable alumni and faculty

Notable alumni of the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa include:

- Daniel Inouye, (B.A. 1950), U.S. Senator[59]

- Daniel Akaka, (B.A. 1952, M.Ed. 1966), U.S. Senator[59]

- Patsy Mink, (B.A. 1948), former U.S. Congresswoman[59]

- Neil Abercrombie, (M.A. 1964, PhD 1974) former governor of Hawaiʻi[59]

- Robert Ballard, (M.S. 1966), oceanographer[59]

- Rick Blangiardi, (M.A 1973), 15th mayor of Honolulu

- Robert Blust, (B.A. 1967, PhD 1974), linguist and Austronesian language expert[60][61]

- Richard Parsons, (B.A. 1968), businessman, former chairman of Citigroup[59]

- Mazie Hirono, (B.A. 1970), U.S. Senator[59]

- Ana Paula Höfling, dance researcher and academic

- Mark Takai, (B.A. 1989, M.P.H. 1991), U.S. Congressman

- Tammy Duckworth, (B.A. 1990), U.S. Senator[59]

- Janet Mock, (B.A. 2004), writer

- Georgia Engel, (B.A. 1967), actress

- Esther T. Mookini, linguist and translator

- Sonny Ganaden, (J.D. 2006[62]), lawyer, journalist and Member of the Hawaii House of Representatives from the 30th District; later a faculty member

- Robert Huey, Japanologist

- Michael Savage, (M.S., 1970, M.A., 1972), author

- Robyn Ah Mow-Santos, 1996, USA Volleyball Team member and former Olympian[59]

- Arsenio Balisacan, PhD, 1985, Socioeconomic Planning Secretary and Director General of the National Economic and Development Authority of the Philippines[59]

- Colleen Hanabusa, (B.A. 1970, M.A. 1975, J.D. 1977), former U.S. Congresswoman[59]

- Linda Taira, (B.A. 1978), former chief congressional correspondent for CNN[59]

- Nainoa Thompson, (B.A. 1986) navigator and former trustee of Kamehameha Schools[59]

- Mark Takai, (B.A. 1990, M.P.H. 1993) U.S. Congressman[59]

- Jay H. Shidler, (B.B.A. 1968) entrepreneur and benefactor of the Shidler College of Business[59]

- Ann Dunham, (Ph.D. 1992) American anthropologist and mother of President Barack Obama[59]

- Pat Saiki, (B.S. 1952), former member of the U.S. House of Representatives and teacher[59]

- Ed Lu, Postdoctoral fellow, former NASA astronaut

- Corinne K. A. Watanabe (J.D. 1971[63]), judge[64]

Notable faculty of the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa include:

- Lee Altenberg, theoretical biologist

- Mapuana Antonio, public health academic

- Tom Apple, physical chemist

- Kim Binsted, computer scientist

- Lyle Campbell, linguist

- Monique Chyba, mathematician

- Edward DeLong, atmospheric science, member of the National Academy of Sciences

- Milton Diamond, anatomist

- Mike Douglass, urban planner

- David Cameron Duffy, conservation biologist

- Kathy Ferguson, political scientist

- Ruth Haas, mathematician

- Richard S. Hamilton, mathematician, member of the National Academy of Sciences

- Bruce Houghton, vulcanologist

- Hope A. Ishii, geophysicist

- Reece Jones, geographer, Guggenheim Fellow

- Kenneth Y. Kaneshiro, evolutionary biologist

- David Karl, microbiologist and oceanographer, member of the National Academy of Sciences

- Klaus Keil, geophysicist

- Patrick Vinton Kirch, archaeologist, member of the National Academy of Sciences

- Denise Konan, economist

- Michelle Manes, mathematician

- Margaret McFall-Ngai, biologist, member of the National Academy of Sciences

- Karen Jean Meech, astronomer

- Michael J. Shapiro, political scientist

- Manfred Steger, sociologist

- Steven M. Stanley, paleontologist and evolutionary biologist, member of the National Academy of Sciences

- Stephen Vargo, marketing

- Bin Wang, meteorologist

- Ryuzo Yanagimachi, biologist, member of the National Academy of Sciences

Notable former faculty members include:

- Isabella Abbott, ethnobotanist

- Glenn Cannon, theatre

- Hampton L. Carson, evolutionary biologist

- Jim Dator, Political-Social Science

- Wilbur Davenport, communications engineering, member of the National Academy of Engineering

- Ruth D. Gates, marine biologist

- George Herbig, astronomer, member of the National Academy of Sciences

- Robert A. Kinzie III, biologist and zoologist

- W. Wesley Peterson, computer scientist and mathematician

- Joseph Rock, botanist

- Shunzo Sakamaki, Japanese studies

- Richard Schmidt, linguist

- Lani Stemmermann, botanist, conservation biologist

- Harold St. John, botanist

- Satosi Watanabe, theoretical physicist

Art on campus

Campus art includes:

- The John Young Museum of Art

- The Jean Charlot collection at the Hamilton Library

- Murals by Jean Charlot: The Relation of Man and Nature in Old Hawaii (1949), Commencement (1953), Inspiration, Study, Creativity (1967), and Mayan Warrior (1970)

- Sculptures by Edward M. Brownlee: Maka ʻIo (Hawk's Eye) (1984), and an untitled reflecting pool with copper and iron sculpture (1962)

- Sculptures by Bumpei Akaji: Maka ʻa e ʻIke Aku i ke Awawa Uluwehi i na Kuahiwi o Mānoa (Glowing Eyes Looking at the Lush Valley in the Mountains of Mānoa) (1979), Manaʻoʻiʻo (Confidence and Faith) (1981), and VVV (1995)

- Murals by Mataumu Toelupe Alisa: Backyard Cooking (1977), and Hula (1982)

- Works by Shige Yamada: ʻAlae a Hina (Mud Hen of Hina) (1977), and Rainbows (1997)

- Sculptures by Greg Clurman: Sumotori (Sumo Wrestler, 1975), and Hina o na Lani (Mother of the Universe, 1975)

- Wa (Harmony), ceramic sculpture by Wayne A. Miyata, 1982

- Founders' Gate, stone arches by Ralph Fishbourne, 1933

- Neumes o Hawaiʻi, ceramic tile bench and planter by Suzi Pleyte Horan, 1976

- Chance Meeting, cast bronze sculpture by George Segal, 1991

- Three untitled murals by Frank M. Moore, 1919

- Silent Sound, brass bas relief by Paul Vanders, 1973

- The Net Effect, cast bronze sculpture by Fred H. Roster, 1982

- Rainbow Spirit, painted copper sculpture by Babs Miyano-Young, 1997

- Untitled ceramic wall sculpture by Isami Enomoto, 1964

- Gate of Hope, red-orange painted steel sculpture by Alexander Liberman, 1972

- Divers, red brass sculpture by Robert Stackhouse, 1991

- Krypton 1 x 6 x 18, mixed media monolith by Bruce Hopper, 1973

- Wisdom of the East, fresco by Affandi, 1967

- Pulelehua (Kamehameha Butterfly), ceramic mural by Bob Flint, 1986

- Makahiki Hoʻokupu (Harvest Celebration), charcoal and sanguine mural by Juliette May Fraser, 1938

- Nana i ke Kumu (Look to the Source), batik triptych by Yvonne Cheng, 1978

- GovDocs, mural by Judith Yamauchi, 1982

- ʻAnuenue #2 (Rainbow #2), three-part woven wall hanging by Reiko Brandon, 1977

- Seated Amida Buddha, 15th-century Japanese wood sculpture with gold over black lacquer

- Epitaph, bronze, steel and granite sculpture by Harold Tovish, 1970

- Grid/Scape, terrazzo and aluminum landscape sculpture by Mamoru Sato, 1982

- The Great Manoa Crack Seed Caper, by Lanny Little and student assistants, 1981

- The Bilger Frescoes representing Air, Water, Earth and Fire by Juliette May Fraser, David Asherman, Sueko Matsueda Kimura and Richard Lucier, 1951–1953

- The Fourth Sign, painted steel sculpture by Tony Smith, 1976

- Varney Circle Fountain, by Henry H. Rempel and Cornelia McIntyre Foley, 1934

- Spirit of Loyalty, cast glass sculpture Rick Mills, 1995

- Mind and Heart, metal sculpture by Frank Sheriff, 1995

- To the Nth Power, steel sculpture by Charles W. Watson, 1971

- Bamboo Forest, mural painted on bricks by Padraic Shigetani, 1978

- Peace Pole, painted obelisk, 1995

- Hawaiʻi Kaʻu Kumu (Hawaiʻi My Teacher), pair of murals by Calley O'Neill and assistants, 1982

- Untitled painted photorealist mural by Donald Yatomi, 1990

- Arctic Portals, stainless steel sculpture by Jan-Peter Stern, 1975

- Adam, bronze sculpture by Satoru Abe, 1954

These artworks are off the main campus:

- East-West Center gallery

- Pleiades, overhead installation of mounted prisms at the Institute for Astronomy by Otto Piene, 1976

- Shadow of Progress mixed media sculpture at the Pacific Biomedical Research Center by Rebecca Steen, 1990

- Woven wall hanging at KHET (2350 Dole Street) by Jean Williams, 1972

See also

- Hawai`i Institute of Marine Biology

- Hawaii Ocean Time-series (HOT)

- University of Hawaiʻi Marching Band

Notes

- ↑ The university's official name is spelled using the traditional Hawaiian names, with an okina in Hawaiʻi and a diacritic in Mānoa

- ↑ Other consists of Multiracial Americans & those who prefer to not say.

- ↑ The percentage of students who received an income-based federal Pell grant intended for low-income students.

- ↑ The percentage of students who are a part of the American middle class at the bare minimum.

References

- ↑ Otsubo Monument Works, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, DLNR, page 85

- ↑ "Meaning of Mālama". https://www.malamalearningcenter.org/meaning-of-m257lama.html.

- ↑ As of June 30, 2020. U.S. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2020 Endowment Market Value and Change in Endowment Market Value from FY19 to FY20 (Report). https://www.nacubo.org/-/media/Documents/Research/2020-NTSE-Public-Tables--Endowment-Market-Values--FINAL-FEBRUARY-19-2021.ashx.

- ↑ Young, Kalbert (December 17, 2019). "Budget request breakdown for 2020 Legislature". University of Hawaiʻi System News. https://www.hawaii.edu/news/2019/12/17/budget-request-2020-legislature/.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "UH Mānoa: At a Glance". http://www.hawaii.edu/campuses/manoa/.

- ↑ "University of Hawai'i at Mānoa". https://www.wscuc.org/institutions/university-of-hawaii-at-manoa/.

- ↑ "University of Hawaiʻi Graphics Standards". University of Hawaiʻi. May 15, 2007. https://www.hawaii.edu/offices/eaur/graphicsguide.html.

- ↑ "University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Catalog". University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. June 14, 2015. http://www.catalog.hawaii.edu/about-uh/university.htm.

- ↑ "Honolulu CDP, HI ." U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved on May 21, 2009.

- ↑ "Overview of University of Hawaii–Manoa". https://www.usnews.com/best-colleges/university-of-hawaii-manoa-1610.

- ↑ Magin, Janis L. "Land deals could breathe new life into Moiliili." Pacific Business News. Sunday July 1, 2007. 1. Retrieved on October 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Carnegie Classifications Institution Lookup". Center for Postsecondary Education. https://carnegieclassifications.iu.edu/lookup/view_institution.php?unit_id=141574.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Mānoa Institutional Research Office". https://manoa.hawaii.edu/miro/quick-facts/.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 "Celebrating the First 100 Years". https://www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/Site/downloads/CTAHRhistory.pdf.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 Kamins, Robert M. (1998). Mālamalama: a history of the University of Hawaiʻi. Robert E. Potter, University of Hawaii. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 0-585-32644-4. OCLC 45843003.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 (in en-US) Ka Palapala 1957. University of Hawaii. 1957.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Yount, David (1996). Who runs the university?: the politics of higher education in Hawaii, 1985-1992. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 0-585-26566-6. OCLC 45727637.

- ↑ "President's Office Collections – University of Hawaii Manoa Library Website" (in en-US). https://manoa.hawaii.edu/library/research/collections/archives/university-archives/administrative-and-governing-bodies/presidents-office-collections/.

- ↑ Karl, David M; University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa (2004). "Chapter 11. Enter Evan Dobelle: "Defining Our Destiny"". UH and the sea: the emergence of marine expeditionary research and oceanography as a field of study at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. p. 11-1. OCLC 56344517. ftp://soest.hawaii.edu/dkarl/misc/dave/UH%26theSea/O-Chapter11.pdf.

- ↑ "New UH Mānoa leadership structure approved". University of Hawaiʻi. April 2, 2019. https://www.hawaii.edu/news/2019/04/02/new-uh-manoa-leadership-structure-approved/.

- ↑ "Normal School" (in en-US). 2015-06-09. https://imagesofoldhawaii.com/territorial-normal-and-training-school/.

- ↑ "Our History" (in en-US). https://coe.hawaii.edu/welcome/history/.

- ↑ "College of Arts, Languages & Letters" (in en-US). https://manoa.hawaii.edu/call/.

- ↑ "The Gift". Shidler.hawaii.edu. 2006-09-06. http://www.shidler.hawaii.edu/tabid/363/Default.aspx.

- ↑ "About Us – Honors Program". http://manoa.hawaii.edu/undergrad/honors/about-our-program/.

- ↑ "Your Honors Journey". http://manoa.hawaii.edu/undergrad/honors/your-honors-journey/.

- ↑ Kyrillidou, Martha; Bland, Les (December 7, 2009). "ARL Statistics 2007–2008". http://publications.arl.org/ARL-Statistics-2007-2008/.

- ↑ "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2020: National/Regional Rank". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. http://www.shanghairanking.com/ARWU2020.html.

- ↑ "America's Top Colleges 2019". Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/top-colleges/list/.

- ↑ "U.S. College Rankings 2020". Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/rankings/united-states/2020#!/page/0/length/25/sort_by/rank/sort_order/asc/cols/stats.

- ↑ "2021 Best National University Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. https://www.usnews.com/best-colleges/rankings/national-universities.

- ↑ "2020 National University Rankings". Washington Monthly. https://washingtonmonthly.com/2020college-guide/national.

- ↑ "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2020". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. 2020. http://www.shanghairanking.com/ARWU2020.html.

- ↑ "QS World University Rankings® 2021". Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. 2020. https://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings/world-university-rankings/2021.

- ↑ "World University Rankings 2021". THE Education Ltd.. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings/2021/world-ranking#!/page/0/length/25/sort_by/rank/sort_order/asc/cols/stats.

- ↑ "Best Global Universities Rankings: 2020". U.S. News & World Report LP. https://www.usnews.com/education/best-global-universities/rankings.

- ↑ "University of Hawaiʻi—Mānoa – U.S. News Best Grad School Rankings". https://www.usnews.com/best-graduate-schools/university-of-hawaii-manoa-141574/overall-rankings.

- ↑ "University of Hawaiʻi-Mānoa – U.S. News Best Global University Rankings". https://www.usnews.com/education/best-global-universities/university-of-hawaii-manoa-141574.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 "Table 20. Higher education R&D expenditures, ranked by FY 2018 R&D expenditures: FYs 2009–18". National Science Foundation. https://ncsesdata.nsf.gov/herd/2018/html/herd18-dt-tab020.html.

- ↑ "University of Hawaii--Manoa Rankings". 2021. https://www.usnews.com/best-colleges/university-of-hawaii-manoa-1610/overall-rankings.

- ↑ "Distance Learning at the University of Hawaiʻi". University of Hawaiʻi. http://www.hawaii.edu/dl/home.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 "UH Mānoa: About UH Mānoa: Facts & Statistics: Research". hawaii.edu. http://manoa.hawaii.edu/about/facts/research/summary.html.

- ↑ "UH Mānoa: About UH Mānoa: Facts & Statistics: Research Awards". hawaii.edu. http://manoa.hawaii.edu/about/facts/research/awards.html.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 "2013 Annual Report Extramural Awards & Expenditures". http://www.ors.hawaii.edu/files/2013_Annual_Report_Extramural_Awards&Expenditures.pdf.

- ↑ "Carnegie Foundation, UH Mānoa". Classifications.carnegiefoundation.org. http://classifications.carnegiefoundation.org/lookup_listings/view_institution.php?unit_id=141574&start_page=institution.php&clq={%22ipug2005_ids%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ipgrad2005_ids%22%3A%22%22%2C%22enrprofile2005_ids%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ugprfile2005_ids%22%3A%22%22%2C%22sizeset2005_ids%22%3A%22%22%2C%22basic2005_ids%22%3A%22%22%2C%22eng2005_ids%22%3A%22%22%2C%22search_string%22%3A%22hawaii%22%2C%22first_letter%22%3A%22%22%2C%22level%22%3A%22%22%2C%22control%22%3A%22%22%2C%22accred%22%3A%22%22%2C%22state%22%3A%22%22%2C%22region%22%3A%22%22%2C%22urbanicity%22%3A%22%22%2C%22womens%22%3A%22%22%2C%22hbcu%22%3A%22%22%2C%22hsi%22%3A%22%22%2C%22tribal%22%3A%22%22%2C%22msi%22%3A%22%22%2C%22landgrant%22%3A%22%22%2C%22coplac%22%3A%22%22%2C%22urban%22%3A%22%22}&print=true.

- ↑ "Association of Pacific Rim Universities – Member Universities". Association of Pacific Rim Universities. http://apru.org/members/member-universities.

- ↑ "50 Years of Progress", University of Hawaiʻi Cancer Center website. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ↑ "UH Cancer Center History", University of Hawaiʻi Cancer Center website. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ↑ "College Scorecard: University of Hawaii at Manoa". United States Department of Education. https://collegescorecard.ed.gov/school/?141574-University-of-Hawaii-at-Manoa.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 "Our Communities | Student Housing Services". http://manoa.hawaii.edu/housing/challs/compare.

- ↑ "Our Communities | Student Housing Services". http://manoa.hawaii.edu/housing/familygrad/halls.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 "About Us | YMCA of Honolulu | Honolulu, Hawaiʻi | www.ymcahonolulu.org". https://www.ymcahonolulu.org/locations/atherton/about-us.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Mendoza, Jim. "For 90 years, Atherton Y called this historic pink building home" (in en). https://www.hawaiinewsnow.com/2021/06/23/90-years-atherton-y-called-this-historic-pink-building-home/.

- ↑ "Demolition of Mary Atherton Richards House starts in July to make way for new UH building" (in en-US). 2021-06-27. https://www.khon2.com/local-news/demolition-of-mary-atherton-richards-house-starts-in-july-to-make-way-for-new-uh-building/.

- ↑ Katz, Andy (December 10, 2010). "Hawaii joins MWC, Big West for 2012". ESPN.com. http://sports.espn.go.com/ncaa/news/story?id=5907111.

- ↑ "Definition of WAHINE" (in en). https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/wahine.

- ↑ Kaneshiro, Jason (May 8, 2021). "Hawaii men's volleyball team sweeps BYU to capture NCAA championship". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. https://www.staradvertiser.com/2021/05/08/sports/sports-breaking/hawaii-mens-volleyball-team-sweeps-byu-to-capture-ncaa-national-championship/.

- ↑ "Article about Monsanto was 'right thing to do'". December 26, 2015. https://www.staradvertiser.com/2015/12/26/editorial/letters/article-about-monsanto-was-right-thing-to-do/.

- ↑ 59.00 59.01 59.02 59.03 59.04 59.05 59.06 59.07 59.08 59.09 59.10 59.11 59.12 59.13 59.14 59.15 59.16 "About UH Mānoa | University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa" (in en-US). https://manoa.hawaii.edu/about/.

- ↑ "About" (in en). https://blusthawaii.wixsite.com/blust/about.

- ↑ Zeitoun, Elizabeth (Chinese: 齊莉莎; pinyin: Qi Li-sha, 2007). Three Western scholars' contributions to Formosan linguistics . Paper presented at "The International Conference for the 100th anniversary of linguistics in Taiwan: In honor of the linguistics pioneer Professor Naoyosi Ogawa". 8–9 September 2007. National Taichung University, Taichung, Taiwan ROC.

- ↑ Nakaso, Dan; Kaya, Travis (2010-07-09). "The 'CJ' is saluted at school". https://www.staradvertiser.com/2010/07/09/hawaii-news/the-cj-is-saluted-at-school/.

- ↑ "Associate Judge Corinne K.A. Watanabe" (in en). https://www.courts.state.hi.us/courts/appeals/associate_judge_corinne_ka_watanabe.

- ↑ "Associate Judge Corinne K.A. Watanabe" (in en). https://www.courts.state.hi.us/courts/appeals/associate_judge_corinne_ka_watanabe.

External links

KSF

KSF