Partition function (number theory)

From HandWiki - Reading time: 12 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 12 min

In number theory, the partition function p(n) represents the number of possible partitions of a non-negative integer n. For instance, p(4) = 5 because the integer 4 has the five partitions 1 + 1 + 1 + 1, 1 + 1 + 2, 1 + 3, 2 + 2, and 4.

No closed-form expression for the partition function is known, but it has both asymptotic expansions that accurately approximate it and recurrence relations by which it can be calculated exactly. It grows as an exponential function of the square root of its argument. The multiplicative inverse of its generating function is the Euler function; by Euler's pentagonal number theorem this function is an alternating sum of pentagonal number powers of its argument.

Srinivasa Ramanujan first discovered that the partition function has nontrivial patterns in modular arithmetic, now known as Ramanujan's congruences. For instance, whenever the decimal representation of n ends in the digit 4 or 9, the number of partitions of n will be divisible by 5.

Definition and examples

For a positive integer n, p(n) is the number of distinct ways of representing n as a sum of positive integers. For the purposes of this definition, the order of the terms in the sum is irrelevant: two sums with the same terms in a different order are not considered to be distinct.

By convention p(0) = 1, as there is one way (the empty sum) of representing zero as a sum of positive integers. Furthermore p(n) = 0 when n is negative.

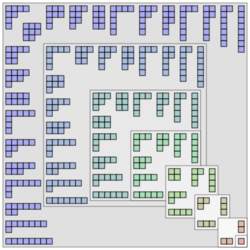

The first few values of the partition function, starting with p(0) = 1, are:

Some exact values of p(n) for larger values of n include:[1] [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} p(100) &= 190,\!569,\!292\\ p(1000) &= 24,\!061,\!467,\!864,\!032,\!622,\!473,\!692,\!149,\!727,\!991 \approx 2.40615\times 10^{31}\\ p(10000) &= 36,\!167,\!251,\!325,\!\dots,\!906,\!916,\!435,\!144 \approx 3.61673\times 10^{106} \end{align} }[/math]

(As of June 2022), the largest known prime number among the values of p(n) is p(1289844341), with 40,000 decimal digits.[2][3] Until March 2022, this was also the largest prime that has been proved using elliptic curve primality proving.[4]

Generating function

The generating function for p(n) is given by[5] [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \sum_{n=0}^\infty p(n)x^n &= \prod_{k=1}^\infty \left(\frac {1}{1-x^k} \right)\\ &=\left(1+x+x^2+x^3+\cdots\right) \left(1+x^2+x^4+x^6+\cdots\right) \left(1+x^3+x^6+x^9+\cdots\right) \cdots \\ &=\frac{1}{1 - x - x^2 + x^5 + x^7 - x^{12} - x^{15} + x^{22} + x^{26} - \cdots}\\ &=1 \Big/ \sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty} (-1)^k x^{k(3k-1)/2}. \end{align} }[/math] The equality between the products on the first and second lines of this formula is obtained by expanding each factor [math]\displaystyle{ 1/(1-x^k) }[/math] into the geometric series [math]\displaystyle{ (1+x^k+x^{2k}+x^{3k}+\cdots). }[/math] To see that the expanded product equals the sum on the first line, apply the distributive law to the product. This expands the product into a sum of monomials of the form [math]\displaystyle{ x^{a_1} x^{2a_2} x^{3a_3} \cdots }[/math] for some sequence of coefficients [math]\displaystyle{ a_i }[/math], only finitely many of which can be non-zero. The exponent of the term is [math]\displaystyle{ n = \sum i a_i }[/math], and this sum can be interpreted as a representation of [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] as a partition into [math]\displaystyle{ a_i }[/math] copies of each number [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math]. Therefore, the number of terms of the product that have exponent [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] is exactly [math]\displaystyle{ p(n) }[/math], the same as the coefficient of [math]\displaystyle{ x^n }[/math] in the sum on the left. Therefore, the sum equals the product.

The function that appears in the denominator in the third and fourth lines of the formula is the Euler function. The equality between the product on the first line and the formulas in the third and fourth lines is Euler's pentagonal number theorem. The exponents of [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] in these lines are the pentagonal numbers [math]\displaystyle{ P_k = k(3k-1)/2 }[/math] for [math]\displaystyle{ k \in \{ 0, 1,-1,2,-2,\dots\} }[/math] (generalized somewhat from the usual pentagonal numbers, which come from the same formula for the positive values of [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math]). The pattern of positive and negative signs in the third line comes from the term [math]\displaystyle{ (-1)^k }[/math] in the fourth line: even choices of [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] produce positive terms, and odd choices produce negative terms.

More generally, the generating function for the partitions of [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] into numbers selected from a set [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] of positive integers can be found by taking only those terms in the first product for which [math]\displaystyle{ k\in A }[/math]. This result is due to Leonhard Euler.[6] The formulation of Euler's generating function is a special case of a [math]\displaystyle{ q }[/math]-Pochhammer symbol and is similar to the product formulation of many modular forms, and specifically the Dedekind eta function.

Recurrence relations

The same sequence of pentagonal numbers appears in a recurrence relation for the partition function:[7] [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} p(n) &= \sum_{k \in \Z\setminus\{0\}} (-1)^{k+1} p(n-k(3k-1)/2) \\ &= p(n-1) + p(n-2)-p(n-5)-p(n-7) +p(n-12) +p(n-15) - p(n-22) -\cdots \end{align} }[/math] As base cases, [math]\displaystyle{ p(0) }[/math] is taken to equal [math]\displaystyle{ 1 }[/math], and [math]\displaystyle{ p(k) }[/math] is taken to be zero for negative [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math]. Although the sum on the right side appears infinite, it has only finitely many nonzero terms, coming from the nonzero values of [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] in the range [math]\displaystyle{ - \frac{\sqrt{24n+1}-1}{6} \leq k \leq \frac{\sqrt{24n+1}+1}{6}. }[/math]

Another recurrence relation for [math]\displaystyle{ p(n) }[/math] can be given in terms of the sum of divisors function σ:[8] [math]\displaystyle{ p(n) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{k=0}^{n-1} \sigma(n-k) p(k). }[/math] If [math]\displaystyle{ q(n) }[/math] denotes the number of partitions of [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] with no repeated parts then it follows by splitting each partition into its even parts and odd parts, and dividing the even parts by two, that[9] [math]\displaystyle{ p(n) = \sum_{k=0}^{\left\lfloor n/2 \right\rfloor} q(n-2k) p(k). }[/math]

Congruences

Srinivasa Ramanujan is credited with discovering that the partition function has nontrivial patterns in modular arithmetic. For instance the number of partitions is divisible by five whenever the decimal representation of [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] ends in the digit 4 or 9, as expressed by the congruence[10] [math]\displaystyle{ p(5k+4) \equiv 0 \pmod 5 }[/math] For instance, the number of partitions for the integer 4 is 5. For the integer 9, the number of partitions is 30; for 14 there are 135 partitions. This congruence is implied by the more general identity [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{k=0}^\infty p(5k+4)x^k = 5~ \frac{ (x^5)^5_\infty } {(x)^6_\infty}, }[/math] also by Ramanujan,[11][12] where the notation [math]\displaystyle{ (x)_\infty }[/math] denotes the product defined by [math]\displaystyle{ (x)_\infty = \prod_{m=1}^\infty (1-x^m). }[/math] A short proof of this result can be obtained from the partition function generating function.

Ramanujan also discovered congruences modulo 7 and 11:[10] [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} p(7k + 5) &\equiv 0 \pmod 7,\\ p(11k + 6) &\equiv 0 \pmod {11}. \end{align} }[/math] The first one comes from Ramanujan's identity[12] [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{k=0}^\infty p(7k+5)x^k = 7~ \frac{ (x^7)^3_\infty} {(x)^4_\infty} +49x ~ \frac{ (x^7)^7_\infty } {(x)^8_\infty}. }[/math]

Since 5, 7, and 11 are consecutive primes, one might think that there would be an analogous congruence for the next prime 13, [math]\displaystyle{ p(13k + a) \equiv 0 \pmod{13} }[/math] for some a. However, there is no congruence of the form [math]\displaystyle{ p(bk + a) \equiv 0 \pmod{b} }[/math] for any prime b other than 5, 7, or 11.[13] Instead, to obtain a congruence, the argument of [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] should take the form [math]\displaystyle{ cbk+a }[/math] for some [math]\displaystyle{ c\gt 1 }[/math]. In the 1960s, A. O. L. Atkin of the University of Illinois at Chicago discovered additional congruences of this form for small prime moduli. For example: [math]\displaystyle{ p(11^3 \cdot 13 \cdot k + 237)\equiv 0 \pmod {13}. }[/math]

Ken Ono (2000) proved that there are such congruences for every prime modulus greater than 3. Later, (Ahlgren Ono) showed there are partition congruences modulo every integer coprime to 6.[14][15]

Approximation formulas

Approximation formulas exist that are faster to calculate than the exact formula given above.

An asymptotic expression for p(n) is given by

- [math]\displaystyle{ p(n) \sim \frac {1} {4n\sqrt3} \exp\left({\pi \sqrt {\frac{2n}{3}}}\right) }[/math] as [math]\displaystyle{ n \to \infty }[/math].

This asymptotic formula was first obtained by G. H. Hardy and Ramanujan in 1918 and independently by J. V. Uspensky in 1920. Considering [math]\displaystyle{ p(1000) }[/math], the asymptotic formula gives about [math]\displaystyle{ 2.4402 \times 10^{31} }[/math], reasonably close to the exact answer given above (1.415% larger than the true value).

Hardy and Ramanujan obtained an asymptotic expansion with this approximation as the first term:[16] [math]\displaystyle{ p(n) \sim \frac{1}{2\pi \sqrt{2}} \sum_{k=1}^v A_k(n)\sqrt{k} \cdot \frac{d}{dn} \left({\frac {1} {\sqrt{n-\frac{1}{24}}} \exp \left[ {\frac{\pi}{k} \sqrt{\frac{2}{3}\left(n-\frac{1}{24}\right)}}\,\,\,\right]}\right) , }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ A_k(n) = \sum_{0 \le m \lt k, \; (m, k) = 1} e^{ \pi i \left( s(m, k) - 2 nm/k \right) }. }[/math] Here, the notation [math]\displaystyle{ (m,k)=1 }[/math] means that the sum is taken only over the values of [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] that are relatively prime to [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math]. The function [math]\displaystyle{ s(m,k) }[/math] is a Dedekind sum.

The error after [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] terms is of the order of the next term, and [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] may be taken to be of the order of [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt n }[/math]. As an example, Hardy and Ramanujan showed that [math]\displaystyle{ p(200) }[/math] is the nearest integer to the sum of the first [math]\displaystyle{ v = 5 }[/math] terms of the series.[16]

In 1937, Hans Rademacher was able to improve on Hardy and Ramanujan's results by providing a convergent series expression for [math]\displaystyle{ p(n) }[/math]. It is[17][18] [math]\displaystyle{ p(n) = \frac{1}{\pi \sqrt{2}} \sum_{k=1}^\infty A_k(n)\sqrt{k} \cdot \frac{d}{dn} \left({ \frac {1} {\sqrt{n-\frac{1}{24}}} \sinh \left[ {\frac{\pi}{k} \sqrt{\frac{2}{3}\left(n-\frac{1}{24}\right)}}\,\,\,\right] }\right) . }[/math]

The proof of Rademacher's formula involves Ford circles, Farey sequences, modular symmetry and the Dedekind eta function.

It may be shown that the [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math]th term of Rademacher's series is of the order [math]\displaystyle{ \exp\left(\frac{\pi}{k} \sqrt\frac{2n}{3} \right) , }[/math] so that the first term gives the Hardy–Ramanujan asymptotic approximation. Paul Erdős (1942) published an elementary proof of the asymptotic formula for [math]\displaystyle{ p(n) }[/math].[19][20]

Techniques for implementing the Hardy–Ramanujan–Rademacher formula efficiently on a computer are discussed by (Johansson 2012), who shows that [math]\displaystyle{ p(n) }[/math] can be computed in time [math]\displaystyle{ O(n^{1/2+\varepsilon}) }[/math] for any [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon\gt 0 }[/math]. This is near-optimal in that it matches the number of digits of the result.[21] The largest value of the partition function computed exactly is [math]\displaystyle{ p(10^{20}) }[/math], which has slightly more than 11 billion digits.[22]

Strict partition function

Definition and properties

A partition in which no part occurs more than once is called strict, or is said to be a partition into distinct parts. The function q(n) gives the number of these strict partitions of the given sum n. For example, q(3) = 2 because the partitions 3 and 1 + 2 are strict, while the third partition 1 + 1 + 1 of 3 has repeated parts. The number q(n) is also equal to the number of partitions of n in which only odd summands are permitted.[23]

| n | q(n) | Strict partitions | Partitions with only odd parts |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | () empty partition | () empty partition |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 1+1 |

| 3 | 2 | 1+2, 3 | 1+1+1, 3 |

| 4 | 2 | 1+3, 4 | 1+1+1+1, 1+3 |

| 5 | 3 | 2+3, 1+4, 5 | 1+1+1+1+1, 1+1+3, 5 |

| 6 | 4 | 1+2+3, 2+4, 1+5, 6 | 1+1+1+1+1+1, 1+1+1+3, 3+3, 1+5 |

| 7 | 5 | 1+2+4, 3+4, 2+5, 1+6, 7 | 1+1+1+1+1+1+1, 1+1+1+1+3, 1+3+3, 1+1+5, 7 |

| 8 | 6 | 1+3+4, 1+2+5, 3+5, 2+6, 1+7, 8 | 1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1, 1+1+1+1+1+3, 1+1+3+3, 1+1+1+5, 3+5, 1+7 |

| 9 | 8 | 2+3+4, 1+3+5, 4+5, 1+2+6, 3+6, 2+7, 1+8, 9 | 1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1, 1+1+1+1+1+1+3, 1+1+1+3+3, 3+3+3, 1+1+1+1+5, 1+3+5, 1+1+7, 9 |

Generating function

The generating function for the numbers q(n) is given by a simple infinite product:[24] [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} q(n)x^n = \prod_{k = 1}^\infty (1 + x^k) = (x;x^2)_{\infty}^{-1}, }[/math] where the notation [math]\displaystyle{ (a;b)_{\infty} }[/math] represents the Pochhammer symbol [math]\displaystyle{ (a;b)_{\infty} = \prod_{k = 0}^{\infty} (1 - ab^{k}). }[/math] From this formula, one may easily obtain the first few terms (sequence A000009 in the OEIS): [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} q(n)x^n = 1+1x+1x^2+2x^3+2x^4+3x^5+4x^6+5x^7+6x^8+8x^9+10x^{10}+\ldots. }[/math] This series may also be written in terms of theta functions as [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} q(n)x^n = \vartheta_{00}(x)^{1/6}\vartheta_{01}(x)^{-1/3}\biggl\{\frac{1}{16\,x}\bigl[\vartheta_{00}(x)^4 - \vartheta_{01}(x)^4\bigr]\biggr\}^{1/24}, }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \vartheta_{00}(x) = 1 + 2\sum_{n = 1}^{\infty} x^{n^2} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \vartheta_{01}(x) = 1 + 2\sum_{n = 1}^{\infty} (-1)^{n} x^{n^2}. }[/math] In comparison, the generating function of the regular partition numbers p(n) has this identity with respect to the theta function: [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} p(n)x^n = (x;x)_{\infty}^{-1} = \vartheta_{00}(x)^{-1/6}\vartheta_{01}(x)^{-2/3}\biggl\{\frac{1}{16\,x}\bigl[\vartheta_{00}(x)^4 - \vartheta_{01}(x)^4\bigr]\biggr\}^{-1/24}. }[/math]

Identities about strict partition numbers

Following identity is valid for the Pochhammer products:

- [math]\displaystyle{ (x;x)_{\infty}^{-1} = (x^2;x^2)_{\infty}^{-1}(x;x^2)_{\infty}^{-1} }[/math]

From this identity follows that formula:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \biggl[\sum_{n=0}^\infty p(n)x^n\biggr] = \biggl[\sum_{n=0}^\infty p(n)x^{2n}\biggr]\biggl[\sum_{n=0}^\infty q(n)x^n\biggr] }[/math]

Therefore those two formulas are valid for the synthesis of the number sequence p(n):

- [math]\displaystyle{ p(2n) = \sum_{k=0}^{n} p(n - k)q(2k) }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ p(2n+1) = \sum_{k=0}^{n} p(n - k)q(2k + 1) }[/math]

In the following, two examples are accurately executed:

- [math]\displaystyle{ p(8) = \sum_{k=0}^{4} p(4 - k)q(2k) = }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ = p(4)q(0) + p(3)q(2) + p(2)q(4) + p(1)q(6) + p(0)q(8) = }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ = 5\times 1 + 3\times 1 + 2\times 2 + 1\times 4 + 1\times 6 = 22 }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ p(9) = \sum_{k=0}^{4} p(4 - k)q(2k + 1) = }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ = p(4)q(1) + p(3)q(3) + p(2)q(5) + p(1)q(7) + p(0)q(9) = }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ = 5\times 1 + 3\times 2 + 2\times 3 + 1\times 5 + 1\times 8 = 30 }[/math]

Restricted partition function

More generally, it is possible to consider partitions restricted to only elements of a subset A of the natural numbers (for example a restriction on the maximum value of the parts), or with a restriction on the number of parts or the maximum difference between parts. Each particular restriction gives rise to an associated partition function with specific properties. Some common examples are given below.

Euler and Glaisher's theorem

Two important examples are the partitions restricted to only odd integer parts or only even integer parts, with the corresponding partition functions often denoted [math]\displaystyle{ p_o(n) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ p_e(n) }[/math].

A theorem from Euler shows that the number of strict partitions is equal to the number of partitions with only odd parts: for all n, [math]\displaystyle{ q(n) = p_o(n) }[/math]. This is generalized as Glaisher's theorem, which states that the number of partitions with no more than d-1 repetitions of any part is equal to the number of partitions with no part divisible by d.

Gaussian binomial coefficient

If we denote [math]\displaystyle{ p(N, M, n) }[/math] the number of partitions of n in at most M parts, with each part smaller or equal to N, then the generating function of [math]\displaystyle{ p(N, M, n) }[/math] is the following Gaussian binomial coefficient:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{n=0}^\infty p(N, M, n)q^n = {N+M \choose M}_q = \frac{(1-q^{N+M})(1-q^{N+M-1})\cdots(1-q^{N+1})} {(1-q)(1-q^2)\cdots(1-q^M)} }[/math]

Asymptotics

Some general results on the asymptotic properties of restricted partition functions are known. If pA(n) is the partition function of partitions restricted to only elements of a subset A of the natural numbers, then:

If A possesses positive natural density α then [math]\displaystyle{ \log p_A(n) \sim C \sqrt{\alpha n} }[/math], with [math]\displaystyle{ C = \pi\sqrt\frac23 }[/math]

and conversely if this asymptotic property holds for pA(n) then A has natural density α.[25] This result was stated, with a sketch of proof, by Erdős in 1942.[19][26]

If A is a finite set, this analysis does not apply (the density of a finite set is zero). If A has k elements whose greatest common divisor is 1, then[27]

- [math]\displaystyle{ p_A(n) = \left(\prod_{a \in A} a^{-1}\right) \cdot \frac{n^{k-1}}{(k-1)!} + O(n^{k-2}) . }[/math]

References

- ↑ Sloane, N. J. A., ed. "Sequence A070177". OEIS Foundation. https://oeis.org/A070177.

- ↑ Caldwell, Chris K. (2017), The Top Twenty, https://primes.utm.edu/top20/page.php?id=54

- ↑ PrimePage Primes: p(1289844341), https://primes.utm.edu/primes/page.php?id=130336, retrieved 30 June 2022

- ↑ The Top Twenty: Elliptic Curve Primality Proof, https://primes.utm.edu/top20/page.php?id=27, retrieved 30 June 2022

- ↑ Abramowitz, Milton; Stegun, Irene (1964), Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables, United States Department of Commerce, National Bureau of Standards, p. 825, ISBN 0-486-61272-4

- ↑ "De partitione numerorum" (in la), Novi Commentarii Academiae Scientiarum Petropolitanae 3: 125–169, 1753, https://eulerarchive.maa.org/pages/E191.html

- ↑ Ewell, John A. (2004), "Recurrences for the partition function and its relatives", The Rocky Mountain Journal of Mathematics 34 (2): 619–627, doi:10.1216/rmjm/1181069871

- ↑ "What is an answer?", American Mathematical Monthly 89 (5): 289–292, 1982, doi:10.2307/2321713

- ↑ Al, Busra; Alkan, Mustafa (2018), "A note on relations among partitions", Proc. Mediterranean Int. Conf. Pure & Applied Math. and Related Areas (MICOPAM 2018), pp. 35–39, https://elibrary.matf.bg.ac.rs/handle/123456789/4699

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers (6th ed.), Oxford University Press, 2008, p. 380, ISBN 978-0-19-921986-5

- ↑ "Ramanujan's unpublished manuscript on the partition and tau functions with proofs and commentary", The Andrews Festschrift (Maratea, 1998), Séminaire Lotharingien de Combinatoire, 42, 1999, Art. B42c, 63, https://www.mathcs.emory.edu/~ono/publications-cv/pdfs/044.pdf

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 The web of modularity: arithmetic of the coefficients of modular forms and [math]\displaystyle{ q }[/math]-series, CBMS Regional Conference Series in Mathematics, 102, Providence, Rhode Island: American Mathematical Society, 2004, p. 87, ISBN 0-8218-3368-5

- ↑ Ahlgren, Scott; Boylan, Matthew (2003), "Arithmetic properties of the partition function", Inventiones Mathematicae 153 (3): 487–502, doi:10.1007/s00222-003-0295-6, Bibcode: 2003InMat.153..487A, https://www.math.sc.edu/~boylan/reprints/nomoreramafinal.pdf

- ↑ "Distribution of the partition function modulo [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math]", Annals of Mathematics 151 (1): 293–307, 2000, doi:10.2307/121118, Bibcode: 2000math......8140O

- ↑ Ahlgren, Scott (2001), "Congruence properties for the partition function", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98 (23): 12882–12884, doi:10.1073/pnas.191488598, PMID 11606715, PMC 60793, Bibcode: 2001PNAS...9812882A, https://www.mathcs.emory.edu/~ono/publications-cv/pdfs/061.pdf

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Asymptotic formulae in combinatory analysis", Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, Second Series 17 (75–115), 1918. Reprinted in Collected papers of Srinivasa Ramanujan, Amer. Math. Soc. (2000), pp. 276–309.

- ↑ The Theory of Partitions, Cambridge University Press, 1976, p. 69, ISBN 0-521-63766-X

- ↑ "On the partition function [math]\displaystyle{ p(n) }[/math]", Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, Second Series 43 (4): 241–254, 1937, doi:10.1112/plms/s2-43.4.241

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "On an elementary proof of some asymptotic formulas in the theory of partitions", Annals of Mathematics, Second Series 43 (3): 437–450, 1942, doi:10.2307/1968802, https://users.renyi.hu/~p_erdos/1942-02.pdf

- ↑ Elementary Methods in Number Theory, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 195, Springer-Verlag, 2000, p. 456, ISBN 0-387-98912-9

- ↑ Johansson, Fredrik (2012), "Efficient implementation of the Hardy–Ramanujan–Rademacher formula", LMS Journal of Computation and Mathematics 15: 341–59, doi:10.1112/S1461157012001088

- ↑ Johansson, Fredrik (March 2, 2014), New partition function record: p(1020) computed, https://fredrikj.net/blog/2014/03/new-partition-function-record/

- ↑ Stanley, Richard P. (1997). Enumerative Combinatorics 1. Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics. 49. Cambridge University Press. Proposition 1.8.5. ISBN 0-521-66351-2.

- ↑ Stanley, Richard P. (1997). Enumerative Combinatorics 1. Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics. 49. Cambridge University Press. Proof of Proposition 1.8.5. ISBN 0-521-66351-2.

- ↑ Nathanson 2000, pp. 475–85.

- ↑ Nathanson 2000, p. 495.

- ↑ Nathanson 2000, pp. 458–64.

External links

|

KSF

KSF