Counter-Enlightenment

Topic: Philosophy

From HandWiki - Reading time: 12 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 12 min

The Counter-Enlightenment refers to a loose collection of intellectual stances that arose during the European Enlightenment in opposition to its mainstream attitudes and ideals. The Counter-Enlightenment is generally seen to have continued from the 18th century into the early 19th century, especially with the rise of Romanticism. Its thinkers did not necessarily agree to a set of counter-doctrines but instead each challenged specific elements of Enlightenment thinking, such as the belief in progress, the rationality of all humans, liberal democracy, and the increasing secularisation of society.

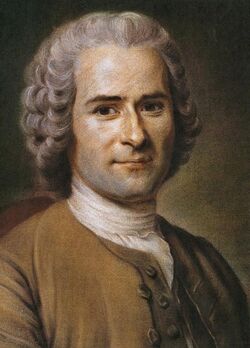

Historical analyses differ on who is to be included among the pioneering figures of the Counter-Enlightenment. In Italy, Giambattista Vico criticised the spread of reductionism and the Cartesian method which he saw as castrating the arts and humanities of the Renaissance.[1] Decades later, Joseph de Maistre in Sardinia and Edmund Burke in United Kingdom both criticised Enlightenment ideals for leading to the bloodshed and tyranny of the French Revolution . Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Johann Georg Hamann were also significant to the rise of the Counter-Enlightenment as forefathers of French and German Romanticism respectively.

In the late 20th century, the concept of the Counter-Enlightenment was popularised by pro-Enlightenment historian Isaiah Berlin[2] as a tradition of relativist, anti-rationalist, vitalist, and organic thinkers stemming largely from Hamann and subsequent German Romantics.[3] While Berlin is largely credited with having refined and promoted the concept, the first known use of the term in English occurred in 1949 and there were several earlier uses of it across other European languages,[4] including by German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche.

Term usage

Early usage

Despite criticism of the Enlightenment being a widely discussed topic in twentieth-century thought, the term 'Counter-Enlightenment' was underdeveloped. It was first mentioned briefly in English in William Barrett's 1949 article "Art, Aristocracy and Reason" in Partisan Review. He used the term again in his 1958 book on existentialism, Irrational Man; however, his comment on Enlightenment criticism was very limited.[2] In Germany, the expression "Gegen-Aufklärung" has a longer history. It was probably coined by Friedrich Nietzsche in "Nachgelassene Fragmente" in 1877.[5]

Lewis White Beck used this term in his Early German Philosophy (1969), a book about Counter-Enlightenment in Germany. Beck claims that there is a counter-movement arising in Germany in reaction to Frederick II's secular authoritarian state. On the other hand, Johann Georg Hamann and his fellow philosophers believe that a more organic conception of social and political life, a more vitalistic view of nature, and an appreciation for beauty and the spiritual life of man have been neglected by the eighteenth century.[2]

Isaiah Berlin

Isaiah Berlin established this term's place in the history of ideas. He used it to refer to a movement that arose primarily in late 18th- and early 19th-century Germany against the rationalism, universalism and empiricism, which are commonly associated with the Enlightenment. Berlin's essay "The Counter-Enlightenment" was first published in 1973, and later reprinted in a collection of his works, Against the Current, in 1981.[6] The term has been more widely used since.

Berlin argues that, while there were opponents of the Enlightenment outside of Germany (e.g. Joseph de Maistre) and before the 1770s (e.g. Giambattista Vico), Counter-Enlightenment thought did not start until the Germans 'rebelled against the dead hand of France in the realms of culture, art and philosophy, and avenged themselves by launching the great counter-attack against the Enlightenment.' This German reaction to the imperialistic universalism of the French Enlightenment and Revolution, which had been forced on them first by the francophile Frederick II of Prussia, then by the armies of Revolutionary France and finally by Napoleon, was crucial to the shift of consciousness that occurred in Europe at this time, leading eventually to Romanticism. The consequence of this revolt against the Enlightenment was pluralism. The opponents to the Enlightenment played a more crucial role than its proponents, some of whom were monists, whose political, intellectual and ideological offspring have been terreur and totalitarianism.

Darrin McMahon

In his book Enemies of the Enlightenment (2001), historian Darrin McMahon extends the Counter-Enlightenment back to pre-Revolutionary France and down to the level of 'Grub Street,' thereby marking a major advance on Berlin's intellectual and Germanocentric view. McMahon focuses on the early opponents to the Enlightenment in France, unearthing a long-forgotten 'Grub Street' literature in the late 18th and early 19th centuries aimed at the philosophes. He delves into the obscure world of the 'low Counter-Enlightenment' that attacked the encyclopédistes and fought to prevent the dissemination of Enlightenment ideas in the second half of the century. Many people from earlier times attacked the Enlightenment for undermining religion and the social and political order. It later became a major theme of conservative criticism of the Enlightenment. After the French Revolution, it appeared to vindicate the warnings of the anti-philosophes in the decades prior to 1789.

Graeme Garrard

Cardiff University professor Graeme Garrard claims that historian William R. Everdell was the first to situate Rousseau as the "founder of the Counter-Enlightenment" in his 1971 dissertation and in his 1987 book, Christian Apologetics in France, 1730–1790: The Roots of Romantic Religion.[7] In his 1996 article, "the Origin of the Counter-Enlightenment: Rousseau and the New Religion of Sincerity", in the American Political Science Review (Vol. 90, No. 2), Arthur M. Melzer corroborates Everdell's view in placing the origin of the Counter-Enlightenment in the religious writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, further showing Rousseau as the man who fired the first shot in the war between the Enlightenment and its opponents.[8] Graeme Garrard follows Melzer in his "Rousseau's Counter-Enlightenment" (2003). This contradicts Berlin's depiction of Rousseau as a philosophe (albeit an erratic one) who shared the basic beliefs of his Enlightenment contemporaries. But similar to McMahon, Garrard traces the beginning of Counter-Enlightenment thought back to France and prior to the German Sturm und Drang movement of the 1770s. Garrard's book Counter-Enlightenments (2006) broadens the term even further, arguing against Berlin that there was no single 'movement' called 'The Counter-Enlightenment'. Rather, there have been many Counter-Enlightenments, from the middle of the 18th century to 20th-century Enlightenment among critical theorists, postmodernists and feminists. The Enlightenment has opponents on all points of its ideological compass, from the far left to the far right, and all points in between. Each of the Enlightenment's challengers depicted it as they saw it or wanted others to see it, resulting in a vast range of portraits, many of which are not only different but incompatible.

James Schmidt

The idea of Counter-Enlightenment has evolved in the following years. The historian James Schmidt questioned the idea of 'Enlightenment' and therefore of the existence of a movement opposing it. As the conception of 'Enlightenment' has become more complex and difficult to maintain, so has the idea of the 'Counter-Enlightenment'. Advances in Enlightenment scholarship in the last quarter-century have challenged the stereotypical view of the 18th century as an 'Age of Reason', leading Schmidt to speculate on whether the Enlightenment might not actually be a creation of its opponents, but the other way round. The fact that the term 'Enlightenment' was first used in 1894 in English to refer to a historical period supports the argument that it was a late construction projected back onto the 18th century.

The French Revolution

By the mid-1790s, the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution fueled a major reaction against the Enlightenment. Many leaders of the French Revolution and their supporters made Voltaire and Rousseau, as well as Marquis de Condorcet's ideas of reason, progress, anti-clericalism, and emancipation central themes to their movement. It led to an unavoidable backlash to the Enlightenment as there were people opposed to the revolution. Many counter-revolutionary writers, such as Edmund Burke, Joseph de Maistre and Augustin Barruel, asserted an intrinsic link between the Enlightenment and the Revolution.[2] They blamed the Enlightenment for undermining traditional beliefs that sustained the ancien regime. As the Revolution became increasingly bloody, the idea of 'Enlightenment' was discredited, too. Hence, the French Revolution and its aftermath have contributed to the development of Counter-Enlightenment thought.[citation needed]

Edmund Burke was among the first of the Revolution's opponents to relate the philosophes to the instability in France in the 1790s. His Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790) refers the Enlightenment as the principal cause of the French revolution. In Burke's opinion, the philosophes provided the revolutionary leaders with the theories on which their political schemes were based.[citation needed]

Augustin Barruel's Counter-Enlightenment ideas were well developed before the revolution. He worked as an editor for the anti-philosophes literary journal, L'Année Littéraire. Barruel argues in his Memoirs Illustrating the History of Jacobinism (1797) that the Revolution was the consequence of a conspiracy of philosophes and freemasons.[citation needed]

In Considerations on France (1797), Joseph de Maistre interprets the Revolution as divine punishment for the sins of the Enlightenment. According to him, "the revolutionary storm is an overwhelming force of nature unleashed on Europe by God that mocked human pretensions."[2]

Romanticism

In the 1770s, the 'Sturm und Drang' movement started in Germany. It questioned some key assumptions and implications of the Aufklärung and the term 'Romanticism' was first coined. Many early Romantic writers such as Chateaubriand, Federich von Hardenberg (Novalis) and Samuel Taylor Coleridge inherited the Counter-Revolutionary antipathy towards the philosophes. All three directly blamed the philosophes in France and the Aufklärer in Germany for devaluing beauty, spirit and history in favour of a view of man as a soulless machine and a view of the universe as a meaningless, disenchanted void lacking richness and beauty. One particular concern to early Romantic writers was the allegedly anti-religious nature of the Enlightenment since the philosophes and Aufklarer were generally deists, opposed to revealed religion. Some historians, such as Hamann, nevertheless contend that this view of the Enlightenment as an age hostile to religion is common ground between these Romantic writers and many of their conservative Counter-Revolutionary predecessors. However, not many have commented on the Enlightenment, except for Chateaubriand, Novalis, and Coleridge, since the term itself did not exist at the time and most of their contemporaries ignored it.[2]

The historian Jacques Barzun argues that Romanticism has its roots in the Enlightenment. It was not anti-rational, but rather balanced rationality against the competing claims of intuition and the sense of justice. This view is expressed in Goya's Sleep of Reason, in which the nightmarish owl offers the dozing social critic of Los Caprichos, a piece of drawing chalk. Even the rational critic is inspired by irrational dream-content under the gaze of the sharp-eyed lynx.[9] Marshall Brown makes much the same argument as Barzun in Romanticism and Enlightenment, questioning the stark opposition between these two periods.

By the middle of the 19th century, the memory of the French Revolution was fading and so was the influence of Romanticism. In this optimistic age of science and industry, there were few critics of the Enlightenment, and few explicit defenders. Friedrich Nietzsche is a notable and highly influential exception. After an initial defence of the Enlightenment in his so-called 'middle period' (late-1870s to early 1880s), Nietzsche turned vehemently against it.

Totalitarianism

In the intellectual discourse of the mid-20th century, two concepts emerged simultaneously in the West: enlightenment and totalitarianism[citation needed]. After World War II, the former re-emerged as a key organizing concept in social and political thought and the history of ideas. The Counter-Enlightenment literature blaming the 18th-century trust in reason for 20th-century totalitarianism also resurged along with it. The locus classicus of this view is Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno's Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947), which traces the degeneration of the general concept of enlightenment from ancient Greece (epitomized by the cunning 'bourgeois' hero Odysseus) to 20th-century fascism. They mentioned little about Soviet communism, only referring to it as a regressive totalitarianism that "clung all too desperately to the heritage of bourgeois philosophy".[10]

The authors take 'enlightenment' as their target including its 18th-century form – which we now call 'The Enlightenment'. They claim it is epitomized by the Marquis de Sade. However, there were philosophers rejecting Adorno and Horkheimer's claim that Sade's moral skepticism is actually coherent, or that it reflects Enlightenment thought.[11]

Many postmodern writers and feminists (e.g. Jane Flax) have made similar arguments.[weasel words] They regard the Enlightenment conception of reason as totalitarian, and as not having been enlightened enough since. For Adorno and Horkheimer, though it banishes myth it falls back into a further myth, that of individualism and formal (or mythic) equality under instrumental reason.

Michel Foucault, for example, argued that attitudes towards the "insane" during the late-18th and early 19th centuries show that supposedly enlightened notions of humane treatment were not universally adhered to, but instead, the Age of Reason had to construct an image of "Unreason" against which to take an opposing stand.[citation needed] Berlin himself, although no postmodernist, argues that the Enlightenment's legacy in the 20th century has been monism (which he claims favours political authoritarianism), whereas the legacy of the Counter-Enlightenment has been pluralism (associates with liberalism).[citation needed] These are two of the 'strange reversals' of modern intellectual history.

See also

- Alasdair MacIntyre

- Aleksandr Dugin

- Anti-intellectualism

- Antiscience

- Augustin Barruel

- Charles Taylor

- Chateaubriand

- Dark Enlightenment (Neo-reactionary movement)

- Darrin McMahon

- Dialectic of Enlightenment

- Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi

- Panagiotis Kondylis

- Monaldo Leopardi

- Giacomo Leopardi

- Friedrich Nietzsche

- Jean-Jacques Lefranc de Pompignan

- Johann Georg Hamann

- John N. Gray

- Joseph de Maistre

- Martin Heidegger

- Walter Benjamin

- Lewis White Beck

- Leo Strauss

- Louis de Bonald

- Carl Schmitt

- Ernst Jünger

- Natural philosophy

- Norbert Elias

- Novalis

- Juan Donoso Cortés

- Søren Kierkegaard

- Voltaire

- Thomas Carlyle[12][lower-alpha 1]

- Julius Evola

- Jacques Derrida

- Gilles Deleuze

- Giorgio Agamben

- Georges Bataille

- Pierre Klossowski

- Charles Maurras

- Reactionary politics

- Curtis Yarvin

Notes

- ↑ It is difficult to label Carlyle's thought, but his famous concept of Hero-Worship as well as his somewhat critical analysis of the French Revolution links him with the Counter-Enlightenment.

Notes

- ↑ Bertland, Alexander. "Giambattista Vico (1668—1744)". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://iep.utm.edu/vico/.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Garrard, Graeme (2006). Counter-enlightenments : from the eighteenth century to the present. Abingdon [England]: Routledge. ISBN 0203645669. OCLC 62895765.

- ↑ Aspects noted by Darrin M. McMahon, "The Counter-Enlightenment and the Low-Life of Literature in Pre-Revolutionary France" Past and Present No. 159 (May 1998:77–112) p. 79 note 7.

- ↑ listed by Henry Hardy in the second edition of Isaiah Berlin, Against the Current: Essays in the History of Ideas (Princeton University Press, 2013), p. xxv, note 1.

- ↑ Nietzsche, Friedrich (1877). Werke: Kristische Gesamtausgabe. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 478.

- ↑ "Archived copy". http://berlin.wolf.ox.ac.uk/published_works/ac/counter-enlightenment.pdf.

- ↑ Garrard, Graeme (2003), Rousseau's Counter-Enlightenment: A Republican Critique of the Philosophes, State University of New York Press, "To my knowledge, the first explicit identification of Rousseau as "founder of the "Counter-Enlightenment" appears in William Everdell's study of Christian apologetics in eighteenth-century France."

- ↑ Melzer, Arthur M. (1996). "The Origin of the Counter-Enlightenment: Rousseau and the New Religion of Sincerity". The American Political Science Review 90 (2): 344–360. doi:10.2307/2082889.

- ↑ Linda Simon, The Sleep of Reason

- ↑ Adorno & Horkeimer, Dialectic of Enlightenment, 1947, pp. 32–33

- ↑ Geoffrey Roche, "Much Sense the Starkest Madness: de Sade’s Moral Scepticism." Angelaki Volume 15, Issue 1 April 2010, pages 45 – 59.

- ↑ Young, B. W. (2018). "The Counter-Enlightenments of Thomas Carlyle". In Kerry, Paul E.; Pionke, Albert D.; Dent, Megan (eds.) Thomas Carlyle and the Idea of Influence. Madison and Teaneck, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 9781683930662.

References

- Barzun, Jacques. 1961. Classic, Romantic, and Modern. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226038520.

- Berlin, Isaiah, "The Counter-Enlightenment" in The Proper Study of Mankind: An Anthology of Essays, ISBN 0-374-52717-2.

- Berlin, Isaiah, Three Critics of the Enlightenment: Vico, Hamann, Herder. (Henry Hardy, editor). Princeton University Press, 2003

- Everdell, William R. Christian Apologetics in France, 1730–1790: The Roots of Romantic Religion. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 1987.

- Everdell, William R. “Complots, Côteries, Conspirations: L’origine de la ‘thèse Barruel’ dans le roman apologétique” (7/6/89) in L’Image de la Révolution française: Communications présentées lors du Congrès Mondial..., vol III, Paris, 1989. Actes du Congrès mondial, “L’Image de la Révolution francaise!, 6-12 juillet, 1989, Pergamon press, p. 1881-1885

- Everdell, William R. The Evangelical Counter-Enlightenment: From Ecstasy to Fundamentalism in Christianity, Judaism, and Islam in the 18th Century. New York: Springer, 2021. ISBN 978-3-030-69761-7

- Garrard, Graeme, Rousseau's Counter-Enlightenment: A Republican Critique of the Philosophes (2003) ISBN 0-7914-5604-8

- Garrard, Graeme, Counter-Enlightenments: From the Eighteenth Century to the Present (2006) ISBN 0-415-18725-7

- Garrard, Graeme, "Isaiah Berlin's Counter-Enlightenment" in Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, ed. Joseph Mali and Robert Wokler (2003), ISBN 0-87169-935-4

- Garrard, Graeme, "The War Against the Enlightenment", European Journal of Political Theory, 10 (2011): 277–86.

- Humbertclaude, Éric, Récréations de Hultazob. Paris: L'Harmattan 2010, ISBN 978-2-296-12546-9 (sur Melech August Hultazob, médecin-charlatan des Lumières Allemandes assassiné en 1743)

- Israel, Jonathan, Enlightenment Contested, Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0-19-954152-2.

- Jung, Theo, "Multiple Counter-Enlightenments: The Genealogy of a Polemics from the Eighteenth Century to the Present", in: Martin L. Davies (ed.), Thinking about the Enlightenment: Modernity and Its Ramifications, Milton Park / New York 2016, 209-226 (PDF).

- Lehner, Ulrich L. The Catholic Enlightenment (2016)

- Lehner, Ulrich L. Women, Enlightenment and Catholicism (2017)

- Masseau, Didier, Les ennemis des philosophes:. l’antiphilosophie au temps des Lumières, Paris: Albin Michel, 2000.

- McMahon, Darrin M., Enemies of the Enlightenment: The French Counter-Enlightenment and the Making of Modernity details the reaction to Voltaire and the Enlightenment in European intellectual history from 1750 to 1830.

- Norton, Robert E. "The Myth of the Counter-Enlightenment," Journal of the History of Ideas, 68 (2007): 635–58.

- Schmidt, James, What Enlightenment Project?, Political Theory, 28/6 (2000), pp. 734–57.

- Schmidt, James, Inventing the Enlightenment: Anti-Jacobins, British Hegelians and the Oxford English Dictionary, Journal of the History of Ideas, 64/3 (2003), pp. 421–43.

- Wolin, Richard, The Seduction of Unreason: The Intellectual Romance with Fascism from Nietzsche to Postmodernism (Princeton University Press) 2004, sets out to trace "the uncanny affinities between the Counter-Enlightenment and postmodernism."

External links

- Isaiah Berlin,"The Counter-Enlightenment", in Dictionary of the History of Ideas (1973)

- Darrin M. McMahon, "The counter-Enlightenment and the low-life of literature in pre-Revolutionary France," from Past & Present, May 1998

KSF

KSF