Critical making

Topic: Philosophy

From HandWiki - Reading time: 7 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 7 min

Critical making refers to the hands-on productive activities that link digital technologies to society. It was invented to bridge the gap between creative physical and conceptual exploration.[1] The purpose of critical making resides in the learning extracted from the process of making rather than the experience derived from the finished output. The term "critical making" was popularized by Matt Ratto, an Associate Professor at the University of Toronto.[2] Ratto describes one of the main goals of critical making as way "to use material forms of engagement with technologies to supplement and extend critical reflection and, in doing so, to reconnect our lived experiences with technologies to social and conceptual critique."[3] "Critical making", as defined by practitioners like Matt Ratto and Stephen Hockema, "is an elision of two typically disconnected modes of engagement in the world — "critical thinking," often considered as abstract, explicit, linguistically based, internal and cognitively individualistic; and "making," typically understood as tacit, embodied, external, and community-oriented."

History of Critical Making

Matt Ratto and Critical Making

Matt Ratto coined the term in 2008[4] to describe his workshop activities that linked conceptual reflection and technical making. This concept explores how learning is influenced by the learner's participation towards creating and/or making things within a technological context.[5] Ratto's first publication to use the term was in 2009. Ratto claims that his goal was to connect the conceptual understanding of technology in social life to materialized activities. By situating himself within the area of "design-oriented research" rather than "research-oriented research," Ratto believes that critical making enhances the shared experience in both theoretical and practical understandings of critical socio-technical issues.[5] However, critical making should not be reviewed as design, but rather as a type of practice. The quality of a critical making lab is evaluated based on the physical "making" process, regardless of quality of the final material production.[6] Prior studies have noted the separation between critical thinking and physical "making". Specifically, experts in technology lack a knowledge of art, and vice versa. However it is very important that technology be embedded in a context rather than being left in isolation, especially when it comes to critical making.

The Critical Making Lab was founded by Matt Ratto in the Faculty of Information, University of Toronto. The Critical Making Lab provides participants tools and basic knowledge of digital technology used in critical making. The mission of the lab is to enhance collaboration, communication, and the practice-based engagement in critical making.[7]

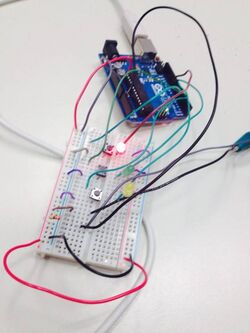

The main focus of critical making is open design.[6]Open design develops a critical perspective on the current institutions, practices and norms of society, reconnecting materiality and morality. Matt Ratto introduces Critical Making as processes of material and conceptual exploration and creation of novel understandings by the makers themselves. Critical Making includes digital software and hardware. Software usually refers to the Raspberry Pi or Arduino. Hardware refers to a computer, or any other device that facilitates an operation.

Garnet Hertz and Critical Making

In 2012, Garnet Hertz adopted the term for a series of ten handmade booklets titled "Critical Making" published in 2012.[8] It explores how hands-on productive work ‐ making ‐ can supplement and extend critical reflection on technology and society. It works to blend and extend the fields of design, contemporary art, DIY/craft and technological development. In this project, 70 different authors - including Norman White, Julian Bleecker, Dunne & Raby, Daniel Charny, Albert Borgmann, Golan Levin, Matt Ratto, Natalie Jeremijenko, McKenzie Wark, Paul Dourish, Mitch Altman, Dale Dougherty, Mark Pauline, Scott Snibbe, Reed Ghazala and others - reflected on the term and critical responses to the maker movement. Generally speaking, Hertz's use of the term critical making is focused around studio production and the creation of objects as "things to think with".[9]

Hertz initially set out to make a zine of about 50 pages but was flooded with almost 300 pages of original content from approximately sixty people. It consisted of academic papers, detailed technical projects, interviews and documented pieces of artwork. He then categorised the information into specific topics thereby producing multiple booklets. The booklet itself is a testament to critical making. It was printed using a hacked photocopier and roughly 100,000 pages were manually folded and stapled to create 300 copies of 10 booklets each. The publication asks us to look at aspects of the DIY culture that go beyond buying an Arduino, getting a MakerBot and reducing DIY to a weekend hobby. These books embrace social issues, the history of technology, activism and politics. The project also stems from a specific disappointment. Recently, Make received a grant from DARPA to create "makerspaces" for teenagers. Everyone who had assumed that a culture built on openness was antithetical to the murkiness that surrounds the military world was bitterly disheartened. However, CM is not the anti-Make Magazine, it is simply an alternative, a forum for electronic DIY practice to discuss hacking, making, kludging, DIYing in a less sanitized, mass-market way.

In 2014, Hertz founded "The Studio for Critical Making" at Emily Carr University of Art and Design as Canada Research Chair in Design and Media Arts. The facility "explores how humanities-based modes of critical inquiry – like the arts and ethics – can be directly applied to building more engaging product concepts and information technologies. The lab works to replace the traditional engineering goals of efficiency, speed or usability with more complex cultural, social and human-oriented values. The end result is technology that is more culturally relevant, socially engaged and personalized." [10]

Other uses of Critical Making

In 2012, John Maeda began using the term while at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD): first as a title for their strategic plan for 2012-2017 and next as part of the title of an edited collection titled "The Art of Critical Making: Rhode Island School of Design on Creative Practice" published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc.[11] Other individuals who use the term critical making to orient their work include Amaranth Borsuk (University of Washington-Bothell), Jentery Sayers (University of Victoria), Roger Whitson (Washington State University), Kari Kraus (University of Maryland), Amy Papaelias (SUNY-New Paltz), and Jessica Barness (Kent State University).

Concepts Related to Critical Making

DIY and Critical Making

Traditional DIY is criticized due to its costs and standards. DIY products are difficult to spread in lower-income areas where issues of cost and ease are more commonly cited (William, 276).[12] Today, TET increases the technological standard of DIY,[13] enhance the modernity of it, and open up a more practical and advanced area for DIY projects to develop. It is not only a lifestyle choices but also a technological product.[14] "DIY activity is not for example seen as a coping practice used by those unable to afford to externalise the activity to formal firms and/or self-employed individuals. Instead, and reflecting the broader cultural turn in retail studies, their explanation for engagement in DIY is firmly grounded in human agency" (Williams, 273).[15]

Speculative Design and Critical Making

According to DiSalvo and Lukens, "Speculative design is an approach to design that emphasizes inquiry, experimentation, and expression, over usability, usefulness or desirability. A particular characteristic of speculative design is that it tends to be future-oriented. However this should not be mistaken as being fantasy-like sense, suggesting, that is "unreal" and therefore dismissible (DiSalvo and Lukens, 2009)."[16]

The term speculative design involves practices from various disciplines, including visionary or futurist forms of architecture, design fiction, and critical design or design for debate instead of referring a specific movement or style. More than just diagrams of unbuilt structures, speculative design aims to explore the space of interaction between culture, technology, and the built environment (Lukens and DiSalvo, 2012, p. 25). Practitioners of speculative design engage in design as a sort of provocation, one that asks uncomfortable questions about the long-term implications of technology. These practices also integrate pairs of concerns that are traditionally separate, such as fact and fiction, science and art, and commerce and academia. This provocation extends to questions about design itself.

3D Printing and Critical Making

3D Printing allows for the relatively cheap and customizable design of objects which are often integrated into critical making projects. There are two types of industrial manufacturing. The first is subtractive manufacturing, which involves shaping a material through a process of chipping / removing some of its substance (think whittling a figure out of wood). The second is additive manufacturing, which is created by adding material into a product. The basic steps of 3D printing are digital design: design the object you want to print using digital design software OR download a design from a website (like Thingiverse, for example), press print and the printer will begin creating a physical version of your digital design. 3D printers use layerization to create objects. 3D printers use a variety of materials to create objects, including plastic, metal and nylon (Flemming, What is 3D printing?). The Makerbot, for example, uses polylactic acid (PLA), a substance derived from corn. The coiled PLA filament is pulled into the machine via a tube and then heated up by the extruder, causing the PLA to melt. This melted material forms the model's layers, which is applied in approximately .02 - 1 millimeter layers. The model is built up until it is finished.

See also

- Critical technical practice

- Critical thinking

- Critical design

- Speculative design

- Maker culture

- Technology

- Arduino

- 3D Printing

References

- ↑ DiSalvo, C (2009). "Design and the Construction of Publics". Design Issues. 1 25: 48. doi:10.1162/desi.2009.25.1.48.

- ↑ http://opendesignnow.org/index.php/article/critical-making-matt-ratto/

- ↑ Ratto, M.; Ree, R. (2012). "Materializing information: 3D printing and social change.". First Monday 17 (7).

- ↑ Ratto, Matt. "Flwr Pwr: Tending the Walled Garden." 2-day Critical Making Workshop for the Walled Garden conference, Virtueel Platform, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, November 20–22, 2008.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Ratto, Matt (2011). "Critical Making: Conceptual and Material Studies in technology and Social Life". The Information Society 27: 252. doi:10.1080/01972243.2011.583819.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Ratto, Matt (2011). "Open Design and Critical Making". Open Design Now: Why Design Cannot Remain Exclusive.

- ↑ "About the Lab". http://criticalmaking.com/about/. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ↑ http://www.conceptlab.com/criticalmaking/

- ↑ http://futureeverything.org/events/critical-making/

- ↑ http://research.ecuad.ca/criticalmaking/

- ↑ http://ca.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-1118517865.html

- ↑ Williams, Colin C. (2004). "A lifestye choice? Evaluating the motives of do-it-yourself (DIY) consumers. I". International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 32 (4/5): 276. doi:10.1108/09590550410534613.

- ↑ Kuznetsov, S.; Paulos, E. (2010). "Rise of the expert amateur: DIY projects, communities, and cultures.". In Proceedings of the 6th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Extending Boundaries: 295–304.

- ↑ Blikstein, P. (2013). "Gears of our childhood: constructionist toolkits, robotics, and physical computing, past and future". In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children: 173–182.

- ↑ Williams, Colin C. (2004). "A lifestye choice? Evaluating the motives of do-it-yourself (DIY) consumers. I". International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 32 (4/5): 273. doi:10.1108/09590550410534613.

- ↑ Lukens, J.; DiSalvo, C. (2011). "Speculative Design and Technological Fluency". International Journal of Learning. 4 3: 23–40. doi:10.1162/ijlm_a_00080.[|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

External links

- Arduino

- Open Design Now

- Raspberry Pi or Arduino

- Critical Making - Paulos Syllabus (Berkeley)

- Critical Making - Hertz (2012)

- The Studio for Critical Making (Emily Carr University of Art and Design)

- John Maeda: The Art of Critical Making

KSF

KSF