Ethics of animal research

Topic: Philosophy

From HandWiki - Reading time: 10 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 10 min

The ethics of animal research is a concept discussed in theology, ethics, philosophy, science, and more recently bioethics. The main discussions in the moral and ethical philosophical community concern themselves with questions as to whether species other than humans can be subject to being morally wronged and whether suffering and being part of a moral community are mutually exclusive.[1] Contemporary views for the use of animals as tools for research often take a philosophical utilitarian position such as reasoning that the overall good produced from results outway the suffering produced by testing on animals. Scientists mostly accept that animals suffer on the basis that their results rely on similarities between animals and humans.[2] Human exceptionalism and Speciesism stem from anthropocentrism and are central recurring themes within the ethics of animal research.[3]

The main concepts that appear throughout ethical discussions of animal research include: Membership in the moral community, Absolutism views, Utilitarian views, and Anthropocentrism such as Speciesism, Human exceptionalism and Personhood theories.

Major Topics

Moral Community Membership

Some ethicists believe that animals have no stature within the moral community and therefore cannot suffer.[1] Animals must be accepted as beings that can be "wronged" in order to be morally considerable. Philosophers who followed in the steps of René Descartes believed the suffering an animal experienced was different to a humans because the suffering they experienced was purely physiological with no moral meaning attached. Under this view membership in the moral community requires the class of beings that recognises moral claims and the class of beings who can suffer moral wrongs are mutually exclusive: if a being recognises a moral wrong it suffers if it cannot recognise moral wrongs it does not suffer.[1]

Speciesism

Speciesism Is the term coined by Richard Ryder in 1970 to explain the (in his view) the prejudicial concept that allocates special rights to particular species in virtue of species membership.[4] Humans are accepted automatically into the moral community by virtue of being homosapien. Critics of Speciesism determine this rejection of species other than homosapians as prejudicial as there is no prima facie or sufficient reason for the preference. In other words, the biological distinguishing factor of being human is irrelevant when talking about what is morally considerable.[1] Human speciesists not of the biological view assert that social meaning is a convention unique to humans which separates humans from the animal kingdom. This form of human exceptionalism has shown not to be the case as numerous animals have shown to portray complex social networks i.e. mice are one of the highest used animals for experimentation have sown complex higher order social interactions shared within diverse communities.[5]

Human exceptionalism & Anthropocentrism

Anthropocentric views see the world as interpreted through the human values and experience. Human exceptionalism is a form of anthropocentrism that is the understanding that humans having distinctive qualities that set them above other beings. Some examples of distinctive qualities outlined by speciesists and human exceptionalism are: the ability to create familial bonds, solving social problems, expressing emotion etc. The position does not hold very strong as not only has each exceptional quality given by human exceptionalism been shown not to be unique to humans human exceptionalism struggle on agreement on what comes under the category of being human, and further, why that alone ought to give them a higher moral status to other beings.[1]

Personhood Theory

Personhood is another form of anthropocentrism; it is the theory that claims that there is a distinction between 'non-persons' and persons and can be summarized as: the necessity for persons to reflect and reason before action, as opposed to the non-persons necessity to act on only impulse.[6] Personhood theory was most notably argued by German philosopher Immanuel Kant who claimed that rationality was the distinguishing feature of persons which made them morally considerable. If a being had rationality then it was of morally considerable value.

American contemporary moral philosopher Christine Korsgaard builds upon Kantian philosophy and argues that non-persons do not have a practical identity for which they can reflect on becasue they do not reason therefore they are not sources of normativity while persons are.[1] Under this view children, the handicapped, the mentally ill do not fall under persons and thus should be excluded from the moral community.

Argument from Marginal Cases

Marginal cases are non-persons who are seem to be accepted as morally considerable despite not being classified as persons. Under the theory of personhood, marginal cases who should be excluded from the moral community are not (children, dementia patients etc), without reason as to why animals don’t deserve this membership to. The problem of marginal cases shows that there seems to be some independent wrong despite being classified as a non-person. Kantian philosopher Allen Wood tackled the issue of non rational persons the notion that if you are a being with the infrastructure for reason, or once had it, then this is enough to be considered morally considerable.[7]

Utilitarian Perspectives

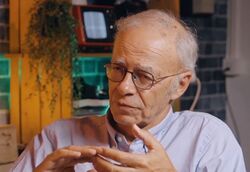

Much of the current ethical justification for the use of animals in research stems from a scientific acceptance of utilitarianism.[2] Results from research gained in the scientific community leads to a far greater well-being to a far greater number.[2] Peter Singer, has disputed this claim as not being an accurate representation of Utilitarianism.[8] Singer is of the view to limit the amount of suffering to all sentient beings and increase positive experiences as he believe this is in each beings interest to avoid suffering.[9]

Utilitarian philosopher Raymond G. Frey (1925–2012) offers an alternative view that builds upon interests. His moral view is that while animals matter morally, the interests of humans matter more when taking both an animals and humans into account becasue human life is more valuable. In Freys view, the value of life is in its quality and richness of capacity and becasue humans have a higher cognitive capacity they live richer lives and are thus more valuable.[10]

Absolutism and Animal Rights

American moral philosopher Tom Regan proposed an extension of the Kantian philosophy of intrinsic value. That the intrinsic value awarded to humans should extend to non persons like children and animals, thus calling for an abolition of animals as tools for research. Regans view is an absolutist moral view as there are no cases where it would be morally acceptable to use animals.[11]

History of ethics in animal research

Ancient philosophy

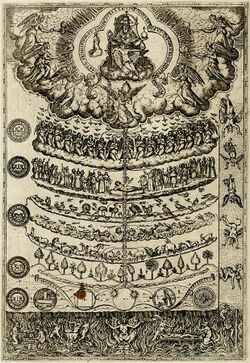

Ethical concepts on animals in research can be traced back to ancient Greece.[12] All life was was ranked on a scale of closeness to the divine gods in "the scale of being" or "scala naturae" and as humans were anthropomorphic to their deities they were given a higher ranking to animals.

Medieval philosophy

Judeo-Christian beliefs of the middle-ages were influenced by the human superiority exhibited in ancient Greece though there was debate between the theological perspectives of the time. Augustine of Hippo believed that animals, earth, water and sky were of the same value: to serve the purpose of humans. Thomas Aquinas believed it was a sin to mistreat an animal if it were someone's property but also condemned the harm of animals as an action that would have repercussions on the human to develop cruelty towards other humans.[13]

The third and fourth century empiricists thought that suffering and death changed the appearance of internal organs and criticised conclusions drawn from experiments on cadavers and vivisections as speculative. They further rejected such experiments as cruel and taboo. [14]

Modern philosophy

The Renaissance reintroduced vivisection for its heuristic value.[15] The 16th century Flemish anatomist and physician Andreas Vesalius and Raldo Colombo utilised animals for both experimentation and educational purposes. The largely accepted founder of modern science Francis bacon reasoned the use of animals in vivisection, though cruel and possibly not accurate was sufficient enough to generate some general understanding.[16]

The Dawn of the age of enlightenment saw an increase in animal experimentation with a defense of the Cartesian mechanism.[17] French philosopher and scientist René Descartes described animals as machine like which was often interpreted as machine without a soul rather than mechanistically. French philosopher and theologist Nicolas Malebranche justified vivisection as only being apparently harmful to animals, following his interpretations from Descartes.[17] Philosopher Baruch Spinoza believed animals could feel but reasoned that becasue their nature was different to humans they could be utilised for any purposes. [18]

Philosophers John Locke and Immanuel Kant shared similar views to Aquinas on cruelty towards living things: that it would morally corrupt humans to be cruel towards each other[19]. Kant was of the anthropocentric view that believed that the moral imperative of humans towards animals was an indirect moral duty and that animals for experimentation could be justified by intent. So while he it was reasoned that harming living things would harm a humans intrinsic dignity if it had worthy justification it could be acceptable.

The 18th century introduced the proposal to shift away from anthropocentric views of a moral duty towards animals and towards kindness to animals for the sake of animals themselves. German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer saw that animal sentience rather than intelligence granted them worth.[20]Genevan philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau claimed that while animals could not understand "natural rights" due to their nature should still be allowed to partake in natural right regardless.[21] British philosopher Jeremy Bentham rejected natural rights and took the now famous utilitarian perspective quoting: "The question is not, Can they reason? Nor, Can they talk? But, Can they suffer?".[22][23] From his utilitarian perspective animal research was acceptable provided it was limited with consideration for overall suffering and that the experiment had a justifiable benefit to humanity with a clear goal and a good chance to accomplish it.[24]

The 19th century saw a shift away from the argument that vivisection revealed poor results as it lost strength with the success from such experiments and moved towards preventing unnecessary harm.[25] Scientists were able to meet these concerns with the prevalence of anesthetics. However some scientists and anti-vivisectionists questioned the administration of such anesthesia giving unlimited freedom to scientists. Scientists now utilised animals as they wished believing that no suffering was being administered.[25] So a movement towards the preservation of the animal of itself arose and whether the use of its life could be justified for humanity.

Contemporary philosophy

The early 20th century had little opposition in terms of animal use in research due to the widely held belief that animals were not suffering under anesthesia. Another possibility was that rodents species were the primary models for research and seen as a lesser species in terms of moral consideration to horses or dogs.[26]

The later 20th century saw opposition again after Australian moral philosopher Peter Singer introduced a strong philosophical standpoint for animal rights arguing that the use of animals for research was based mostly on the the concept of speciesism which he believes is no less justifiable than racism or sexism. [27] Singers form of utilitarianism proposes that actions should aim to balance the interests of those affected. According to the principle of equal consideration of interests all sentient beings deserve to avoid pain and share positive experiences. Priority is given to relieve the greater suffering. Singer does not perceive animal research as always morally wrong as he does agree that a being with a disease that has higher cognition can suffer more than a being that shows lower cognition with the same disease. [28]

American Philosopher Tom Regan would introduce a more absolutist view to animal research by proposing that we extend the Kantian view of intrinsic value to all sentient beings, he argues this point from the the problem of marginal cases: that children and the handicapped who are without the capacity to understand such rights are often afforded them despite this. The respect for sentient animals should be taken as absolute whereby they are violated in only the extreme like self defence. Regan's view calls for the abolition of animals in research and has become the main theoretical reference for the animal rights movement.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Gruen, Lori (2017-09-21). "The Moral Status of Animals". Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/moral-animal/#MoraSignAnimMoraClai.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Khoo, Shaun (2018-02-14). "Justifiability and Animal Research in Health: Can Democratisation Help Resolve Difficulties?". Animals 8 (2): 28. doi:10.3390/ani8020028. ISSN 2076-2615. PMID 29443894.

- ↑ Frey, R. G., "6. Utilitarianism and Animals", The Oxford Handbook of Animal Ethics (Oxford University Press): pp. 172–198, ISBN 9780195371963, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195371963.003.0007, retrieved 2018-10-21

- ↑ "Animal revolution: changing attitudes towards speciesism". Choice Reviews Online 28 (01): 28–0297-28-0297. 1990-09-01. doi:10.5860/choice.28-0297. ISSN 0009-4978. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/choice.28-0297.

- ↑ Shemesh, Yair; Sztainberg, Yehezkel; Forkosh, Oren; Shlapobersky, Tamar; Chen, Alon; Schneidman, Elad (2013-09-03). "High-order social interactions in groups of mice" (in en). eLife 2: e00759. doi:10.7554/elife.00759. ISSN 2050-084X. PMID 24015357. PMC 3762363. https://elifesciences.org/articles/00759.

- ↑ Korsgaard, Christine M. (1996). The Sources of Normativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511554476. ISBN 9780511554476.

- ↑ Wood, Allen W. (1998-06-01). "I–Allen W. Wood" (in en). Aristotelian Society Supplementary Volume 72 (1): 189–210. doi:10.1111/1467-8349.00042. ISSN 0309-7013. https://academic.oup.com/aristoteliansupp/article/72/1/189/1780011.

- ↑ Singer, Peter; Mason, Jim (2006-11-01). "Are we what we eat?". Soundings 34 (34): 67–71. doi:10.3898/136266206820466020. ISSN 1362-6620.

- ↑ Singer, Peter, "About Ethics", Practical Ethics (Cambridge University Press): pp. 1–15, ISBN 9780511975950, http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511975950.002, retrieved 2018-10-20

- ↑ Frey, R. G., "6. Utilitarianism and Animals", The Oxford Handbook of Animal Ethics (Oxford University Press): pp. 172–198, ISBN 9780195371963, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195371963.003.0007, retrieved 2018-10-21

- ↑ Benson, John (1978). "Animal Rights and Human Obligations Edited by Tom Regan and Peter Singer Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1976, vi + 250 pp.". Philosophy 53 (206): 576–577. doi:10.1017/s0031819100026462. ISSN 0031-8191. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/s0031819100026462.

- ↑ Franco, Nuno (2013-03-19). "Animal Experiments in Biomedical Research: A Historical Perspective". Animals 3 (1): 238–273. doi:10.3390/ani3010238. ISSN 2076-2615. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ani3010238.

- ↑ Tom., Regan, (1989). Animal rights and human obligations. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0130368644. OCLC 611064153. http://worldcat.org/oclc/611064153.

- ↑ Nutton, Vivian (1990). "Heinrich Von Staden, Herophilus: the art of medicine in early Alexandria, Cambridge University Press, 1989, 8vo, pp. xliii, 666, £75.00, $140.00.". Medical History 34 (01): 101–102. doi:10.1017/s0025727300050341. ISSN 0025-7273. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/s0025727300050341.

- ↑ Mendelsohn, E. (1964-07-10). "Andreas Vesalius of Brussels, 1514-1564. C. D. O'Malley. University of California Press, Berkeley, 1964. xvi + 480 pp. Illus. $10". Science 145 (3628): 146–146. doi:10.1126/science.145.3628.146. ISSN 0036-8075. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.145.3628.146.

- ↑ Bacon, Francis (1824). The works of Francis Bacon baron of Verulam, viscount St. Albans, and lord high chancellor of England.. London :: Printed for W. Baynes and Son,. http://dx.doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.104671.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Tansey, E. M. (1988). "Nicholaas A. Rupke (editor), Vivisection in historicalperspective, London, Croom Helm, 1987, 8vo, pp. x, 373, illus., £45.00.". Medical History 32 (02): 225–226. doi:10.1017/s002572730004816x. ISSN 0025-7273. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/s002572730004816x.

- ↑ "6843, 1804-07-09, UDNY (Robert), Teddington, Middlesex †". http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/2210-7886_asc-6843.

- ↑ 1632-1704., Locke, John, (1778). Some thoughts concerning education. Printed by J. Kiernan, for T. Walker, No. 79, Dame-Street. OCLC 153689181. http://worldcat.org/oclc/153689181.

- ↑ Landor, Alfred (1981). "Arthur Schopenhauer. Prize Essay on the Basis of Morality". Philosophy and History 14 (2): 136–138. doi:10.5840/philhist1981142124. ISSN 0016-884X. http://dx.doi.org/10.5840/philhist1981142124.

- ↑ Correa de Sa, Daniel D.; Lustgarten, Daniel L. (2012-05-22). "Electrophysiology for CliniciansBarrero GarciaMiguel A.KhairyPaulMacleLaurentNattelStanley, eds.254 pages. Minneapolis, MN, USA: Cardiotext Publishing LLC,2011. $69.00.". Circulation 125 (20). doi:10.1161/circulationaha.111.077412. ISBN 978-1935395140. ISSN 0009-7322. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.111.077412.

- ↑ Bentham, Jeremy (2002-03-07), "Observations on the Draughts of Declarations-of-Rights Presented to the Committee of the Constitution of the National Assembly of France", The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham: Rights, Representation, and Reform: Nonsense upon Stilts and Other Writings on the French Revolution (Oxford University Press): pp. 177–192, ISBN 9780199248636, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oseo/instance.00077257, retrieved 2018-10-20

- ↑ Bentham, Jeremy (1789-01-01), "An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation", The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham: An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (Oxford University Press), ISBN 9780198205166, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oseo/instance.00077240, retrieved 2018-10-20

- ↑ Crimmins, James E. (1985). "Bentham and the Oppressed Lea Campos Boralevi Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1984, pp. xii, 248". Canadian Journal of Political Science 18 (02): 421. doi:10.1017/s0008423900030511. ISSN 0008-4239. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/s0008423900030511.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Preece, Rod (2011), "The History of Animal Ethics in Western Culture", The Psychology of the Human-Animal Bond (Springer New York): pp. 45–61, ISBN 9781441997609, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-9761-6_3, retrieved 2018-10-20

- ↑ Guerrini, Anita (2004). "Deborah Rudacille. The Scalpel and the Butterfly: The Conflict between Animal Research and Animal Protection. 390 pp., notes, bibl., index. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001. $17.95 (paper).". Isis 95 (1): 168–169. doi:10.1086/423595. ISSN 0021-1753. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/423595.

- ↑ Singer, Peter (1990). Animal Liberation. New York: New York Review of Books. pp. 37–40.

- ↑ Singer, Peter, "Equality for Animals?", Practical Ethics (Cambridge University Press): pp. 48–70, ISBN 9780511975950, http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511975950.004, retrieved 2018-10-20

KSF

KSF