Fatalism

Topic: Philosophy

From HandWiki - Reading time: 19 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 19 min

Fatalism is a belief[1] and philosophical doctrine[2][3] which considers the entire universe as a deterministic system and stresses the subjugation of all events, actions, and behaviors to fate or destiny, which is commonly associated with the consequent attitude of resignation in the face of future events which are thought to be inevitable and outside of human control.[1][2][3][4]

Definition

The term "fatalism" can refer to any of the following ideas:

- Broadly, any view according to which human beings are powerless to do anything other than what they actually do.[1][2][3][4] Included in this is the belief that all events are decided by fate and are outside human control, hence humans have no power to influence the future or indeed the outcome of their own thoughts and actions.[1][3][4][5]

More specifically:

- Theological fatalism, according to which free will is incompatible with the existence of an omniscient God who has foreknowledge of all future events.[6] This is very similar to theological determinism.[lower-alpha 1]

- Logical fatalism, according to which propositions about the future which we take to currently be either true or false can only be true or false if future events are already determined.[2]

- Causal determinism, which is usually treated as distinct from fatalism, on the grounds that it requires only the determination of each successive state in a system by that system's prior state, rather than the final state of a system being predetermined.[2]

- The view that the appropriate reaction to the inevitability of some future event is acceptance or resignation, rather than resistance. For instance, 19th-century German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche discusses what he calls "Turkish fatalism" (Türkenfatalismus) in his essay The Wanderer and His Shadow (1880),[4] where he makes no distinction between the terms "fate" and "fatalism".[4] This view is closer to everyday use of the word "fatalism" and parallels defeatism.[1][4]

Religion

Throughout history, the belief that the entire universe is a deterministic system subject to the will of fate or destiny has been articulated in both Eastern and Western religions, philosophy, music, and literature.[1][2][3][4][5]

The ancient Arabs that inhabited the Arabian Peninsula before the advent of Islam used to profess a widespread belief in fatalism (ḳadar) alongside a fearful consideration for the sky and the stars as divine beings, which they held to be ultimately responsible for every phenomenon that occurs on Earth and for the destiny of humankind.[7] Accordingly, they shaped their entire lives in accordance with their interpretations of astral configurations and phenomena.[7]

In the I Ching and philosophical Taoism, the ebb and flow of favorable and unfavorable conditions suggests the path of least resistance is effortless (see: Wu wei). In the philosophical schools of the Indian Subcontinent, the concept of karma deals with similar philosophical issues to the Western concept of determinism. Karma is understood as a spiritual mechanism which causes the eternal cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (saṃsāra).[8] Karma, either positive or negative, accumulates according to an individual's actions throughout their life, and at their death determines the nature of their next life in the cycle of Saṃsāra.[8] Most major religions originating in India hold this belief to some degree, most notably Hinduism,[8] Jainism, Sikhism, and Buddhism.

The views on the interaction of karma and free will are numerous, and diverge from each other greatly. For example, in Sikhism, god's grace, gained through worship, can erase one's karmic debts, a belief which reconciles the principle of karma with a monotheistic god one must freely choose to worship.[9] Jainists believe in a sort of compatibilism, in which the cycle of Saṃsara is a completely mechanistic process, occurring without any divine intervention. The Jains hold an atomic view of reality, in which particles of karma form the fundamental microscopic building material of the universe.

Ājīvika

In ancient India, the Ājīvika school of philosophy founded by Makkhali Gosāla (around 500 BCE), otherwise referred to as "Ājīvikism" in Western scholarship,[10] upheld the Niyati ("Fate") doctrine of absolute fatalism or determinism,[10][11][12] which negates the existence of free will and karma, and is therefore considered one of the nāstika or "heterodox" schools of Indian philosophy.[10][11][12] The oldest descriptions of the Ājīvika fatalists and their founder Gosāla can be found both in the Buddhist and Jaina scriptures of ancient India.[10][12] The predetermined fate of all sentient beings and the impossibility to achieve liberation (mokṣa) from the eternal cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (saṃsāra) was the major distinctive philosophical and metaphysical doctrine of this heterodox school of Indian philosophy,[10][11][12] annoverated among the other Śramaṇa movements that emerged in India during the Second urbanization (600–200 BCE).[10]

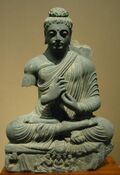

Buddhism

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhist philosophy |

|---|

|

Buddhist philosophy contains several concepts which some scholars describe as deterministic to various levels. However, the direct analysis of Buddhist metaphysics through the lens of determinism is difficult, due to the differences between European and Buddhist traditions of thought.[13]

One concept which is argued to support a hard determinism is the doctrine of dependent origination (pratītyasamutpāda) in the early Buddhist texts, which states that all phenomena (dharma) are necessarily caused by some other phenomenon, which it can be said to be dependent on, like links in a massive, never-ending chain; the basic principle is that all things (dharmas, phenomena, principles) arise in dependence upon other things, which means that they are fundamentally "empty" or devoid of any intrinsic, eternal essence and therefore are impermanent.[13][14] In traditional Buddhist philosophy, this concept is used to explain the functioning of the eternal cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (saṃsāra); all thoughts and actions exert a karmic force that attaches to the individual's consciousness, which will manifest through reincarnation and results in future lives.[13] In other words, righteous or unrighteous actions in one life will necessarily cause good or bad responses in another future life or more lives.[15] The early Buddhist texts and later Tibetan Buddhist scriptures associate dependent arising with the fundamental Buddhist doctrines of emptiness (śūnyatā) and non-self (anattā).[13][14]

Another Buddhist concept which many scholars perceive to be deterministic is the doctrine of non-self (anattā).[13] In Buddhism, attaining enlightenment involves one realizing that neither in humans nor any other sentient beings is there a fundamental core of permanent being, identity, or personality which can be called the "soul", and that all sentient beings (including humans) are instead made of several, constantly changing factors which bind them to the eternal cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (saṃsāra).[13][14] Sentient beings are composed of the five aggregates of existence (skandha): matter, sensation, perception, mental formations, and consciousness.[13] In the Saṃyutta Nikāya of the Pāli Canon, the historical Buddha is recorded as saying that "just as the word 'chariot' exists on the basis of the aggregation of parts, even so the concept of 'being' exists when the five aggregates are available."[16] The early Buddhist texts outline different ways in which dependent origination is a middle way between different sets of "extreme" views (such as "monist" and "pluralist" ontologies or materialist and dualist views of mind-body relation).[17] In the Kaccānagotta Sutta of the Pāli Canon (SN 12.15, parallel at SA 301), the historical Buddha stated that "this world mostly relies on the dual notions of existence and non-existence" and then explains the right view as follows:[18]

But when you truly see the origin of the world with right understanding, you won't have the notion of non-existence regarding the world. And when you truly see the cessation of the world with right understanding, you won't have the notion of existence regarding the world.[19]

Some Western scholars argue that the concept of non-self necessarily disproves the ideas of free will and moral responsibility.[13][20] If there is no autonomous self, in this view, and all events are necessarily and unchangeably caused by others, then no type of autonomy can be said to exist, moral or otherwise.[20] However, other scholars disagree, claiming that the Buddhist conception of the universe allows for a form of compatibilism.[13] Buddhism perceives reality occurring on two different levels: the ultimate reality, which can only be truly understood by the enlightened ones, and the illusory or false reality of the material world, which is considered to be "real" or "true" by those who are ignorant about the nature of metaphysical reality; i.e., those who still haven't achieved enlightenment.[13][14] Therefore, Buddhism perceives free will as a notion belonging to the illusory belief in the unchanging self or personhood that pertains to the false reality of the material world, while concepts like non-self and dependent origination belong to the ultimate reality; the transition between the two can be truly understood, Buddhists claim, by one who has attained enlightenment.[13][14][20]

Determinism and predeterminism

While the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, fatalism, determinism, and predeterminism are distinct, as each emphasizes a different aspect of the futility of human will or the foreordination of destiny. However, all these doctrines share common ground.

Determinists generally agree that human actions affect the future but that human action is itself determined by a causal chain of prior events. Their view does not accentuate a "submission" to fate or destiny, whereas fatalists stress an acceptance of future events as inevitable. Determinists believe the future is fixed specifically due to causality; fatalists and predeterminists believe that some or all aspects of the future are inescapable but, for fatalists, not necessarily due to causality.[21]

Fatalism is a looser term than determinism. The presence of historical "indeterminisms" or chances, i.e. events that could not be predicted by sole knowledge of other events, is an idea still compatible with fatalism. Necessity (such as a law of nature) will happen just as inevitably as a chance—both can be imagined as sovereign.[2] This idea has roots in Aristotle's work, "De interpretatione".[22]

Theological fatalism is the thesis that infallible foreknowledge of a human act makes the act necessary and hence unfree. If there is a being who knows the entire future infallibly, then no human act is free.[23] The early Islamic philosopher, Al Farabi, makes the case that if God does in fact know all human actions and choices, then Aristotle's original solution to this dilemma stands.[24]

Idle argument

One famous ancient argument regarding fatalism was the so-called Idle Argument. It argues that if something is fated, then it would be pointless or futile to make any effort to bring it about. The Idle Argument was described by Origen and Cicero and it went like this:

- If it is fated for you to recover from this illness, then you will recover whether you call a doctor or not.

- Likewise, if you are fated not to recover, you will not do so whether you call a doctor or not.

- But either it is fated that you will recover from this illness, or it is fated that you will not recover.

- Therefore, it is futile to consult a doctor.[25][26]

The Idle Argument was anticipated by Aristotle in his De Interpretatione chapter 9. The Stoics considered it to be a sophism and the Stoic Chrysippus attempted to refute it by pointing out that consulting the doctor would be as much fated as recovering. He seems to have introduced the idea that in cases like that at issue two events can be co-fated, so that one cannot occur without the other.[27]

Logical fatalism and the argument from bivalence

Arguments for logical fatalism go back to antiquity. The argument from bivalence depends not on causation or physical circumstances but rather is based on logical truths and metaphysical necessity. There are numerous versions of this argument, including those by Aristotle[28] and Richard Clyde Taylor.[5]

The key idea of logical fatalism is that there exists necessarily true or false future describing propositions, or statements about what is going to happen in the future, and that there is something metaphysically necessary about the truth value of these statements.[2] So, for example, if it is true today that tomorrow there will be a sea battle, then there cannot fail to be a sea battle tomorrow, since otherwise it would not be true today that such a battle will take place tomorrow.

There are two main forms of responses to logical fatalism.[29] The first response is concerned with logical fatalism's reliance on the principle of bivalence, which says that a proposition is necessarily either true or false. If one wants to reject logical fatalism, one move to take is to reject that this principle applies to future describing propositions. Aristotle is famously attributed as making this move, though there are views that he does not.[2][30] This response works well with an A-theory of time, which says that time is fundamentally tensed, and events can be classified as past, present, and perhaps, future.[31] A-theory supports views of time that say that the future does not yet exist, like presentism. Relating to logical fatalism, If the future is considered to be undetermined, meaning that the truth value of a statement can only be determined once the event occurs, then the principle of bivalence can be rejected.[32] However, the B-theory of time sees the past and future as being just as real as the present. On a B-theory of time, future facts do exist, and therefore the solution to reject the principle of bivalence on the grounds of undetermined future propositions does not work.[2]

The second response can be attributed to William of Ockham, and is often called the Ockhamist Response.[29][33] This response, essentially, challenges the idea that we cannot affect the past truth of future describing propositions.[29] The truth value of propositions describing the future, then, may not be as metaphysically necessary as we think.[2][33]

The argument for logical fatalism and its responses relate closely to the problem of future contingents. There are responses to this problem that allow one to also overcome logical fatalism. The third truth value view says that future contingents can have a third value which is beyond truth or falsity.[34] The all-false view says that all future contingents are false.[34]

Criticism

Semantic equivocation

One criticism comes from the novelist David Foster Wallace, who in a 1985 paper "Richard Taylor's Fatalism and the Semantics of Physical Modality" suggests that Richard Taylor reached his conclusion of fatalism only because his argument involved two different and inconsistent notions of impossibility.[35] Wallace did not reject fatalism per se, as he wrote in his closing passage, "if Taylor and the fatalists want to force upon us a metaphysical conclusion, they must do metaphysics, not semantics. And this seems entirely appropriate."[35] Willem deVries and Jay Garfield, both of whom were advisers on Wallace's thesis, expressed regret that Wallace never published his argument.[35] In 2010, the thesis was, however, published posthumously as Time, Fate, and Language: An Essay on Free Will.

See also

Notes

- ↑ For further informations, see the article on predeterminism.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Durmaz, H.; Çapik, C. (March 2023). "Are Health Fatalism and Styles of Coping with Stress Affected by Poverty? A Field Study". Iranian Journal of Public Health (Tehran University of Medical Sciences) 52 (3): 575–583. doi:10.18502/ijph.v52i3.12140. ISSN 2251-6093. PMID 37124894. "Fatalism is the belief that everything an individual may encounter in his life is determined against his will and that this destiny cannot be changed by effort. In a fatalistic attitude, individuals believe that they cannot control their lives and that there is no point in making choices. Fatalism is a response to overwhelming threats that seem uncontrollable.".

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 Zalta, Edward N., ed (Winter 2018). "Fatalism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University: Center for the Study of Language and Information. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2018/entries/fatalism/. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "On Fate and Fatalism". Philosophy East and West (University of Hawaii Press) 53 (4): 435–454. October 2003. doi:10.1353/pew.2003.0047.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 "Amor dei and Amor fati: Spinoza and Nietzsche". The Other Nietzsche. SUNY Press. 1994. pp. 79–81. ISBN 9781438420929. https://books.google.com/books?id=qytXzUMTEfQC&pg=PA79. "Turkish fatalism contains the fundamental error of placing man and fate opposite each other like two separate things: Man, it says, can strive against fate, can try to defeat it, but in the end it always remains the winner, for which reason the smartest thing to do is to give up or live just any way at all. The truth is that every man himself is a piece of fate; when he thinks he is striving against fate in the way described, fate is being realized here, too; the struggle is imaginary, but so is resignation to fate; all these imaginary ideas are included in fate. The fear that most people have of the doctrine of determinism of the will is precisely the fear of this Turkish fatalism. They think man will give up weakly and stand before the future with folded hands because he cannot change anything about it; or else he will give free rein to his total caprice because even this cannot make what is once determined still worse. The follies of man are just as much a part of fate as his cleverness: this fear of the belief in fate is also fate. You yourself, poor frightened man, are the invincible Moira reigning far above the gods; for everything that comes, you are blessing or curse and in any case the bonds in which the strongest man lies. In you the whole future of the human world is predetermined; it will not help you if you are terrified of yourself."

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Fatalism". The Philosophical Review (Duke University Press on behalf of the Sage School of Philosophy at Cornell University) 71 (1): 56–66. January 1962. doi:10.2307/2183681. ISSN 1558-1470.

- ↑ Zagzebski, Linda. "Foreknowledge and Free Will". https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/free-will-foreknowledge/.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 al-Abbasi, Abeer Abdullah (August 2020). "The Arabsʾ Visions of the Upper Realm". Marburg Journal of Religion (University of Marburg) 22 (2): 1–28. doi:10.17192/mjr.2020.22.8301. ISSN 1612-2941. https://archiv.ub.uni-marburg.de/ep/0004/article/view/8301/8105. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Heilijgers, Dory H.; Houben, Jan E. M.; van Kooij, Karel, eds (2019). "Chapter 1 – The Hindu Doctrine of Transmigration: Its Origin and Background". Vedic Cosmology and Ethics: Selected Studies. Gonda Indological Studies. 19. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 3–19. doi:10.1163/9789004400139_002. ISBN 978-90-04-40013-9.

- ↑ House, H. Wayne. 1991. "Resurrection, Reincarnation, and Humanness." Bibliotheca Sacra 148(590). Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Balcerowicz, Piotr (2016). "Determinism, Ājīvikas, and Jainism". Early Asceticism in India: Ājīvikism and Jainism. Routledge Advances in Jaina Studies (1st ed.). London and New York: Routledge. pp. 136–174. ISBN 9781317538530. https://books.google.com/books?id=nfOPCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA136. "The Ājīvikas' doctrinal signature was indubitably the idea of determinism and fate, which traditionally incorporated four elements: the doctrine of destiny (niyati-vāda), the doctrine of predetermined concurrence of factors (saṅgati-vāda), the doctrine of intrinsic nature (svabhāva-vāda), occasionally also linked to materialists, and the doctrine of fate (daiva-vāda), or simply fatalism. The Ājīvikas' emphasis on fate and determinism was so profound that later sources would consistently refer to them as niyati-vādins, or ‘the propounders of the doctrine of destiny’."

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Leaman, Oliver, ed (1999). "Fatalism". Key Concepts in Eastern Philosophy. Routledge Key Guides (1st ed.). London and New York: Routledge. pp. 80–81. ISBN 9780415173636. https://books.google.com/books?id=_4crBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA80. "Fatalism. Some of the teachings of Indian philosophy are fatalistic. For example, the Ajivika school argued that fate (nyati) governs both the cycle of birth and rebirth, and also individual lives. Suffering is not attributed to past actions, but just takes place without any cause or rationale, as does relief from suffering. There is nothing we can do to achieve moksha, we just have to hope that all will go well with us. [...] But the Ajivikas were committed to asceticism, and they justified this in terms of its practice being just as determined by fate as anything else."

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 "Chapter XII: Niyati". History and Doctrines of the Ājīvikas, a Vanished Indian Religion. Lala L. S. Jain Series (1st ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. 1981. pp. 224–238. ISBN 9788120812048. OCLC 633493794. https://books.google.com/books?id=BiGQzc5lRGYC&pg=PA224. "The fundamental principle of Ājīvika philosophy was Fate, usually called Niyati. Buddhist and Jaina sources agree that Gosāla was a rigid determinist, who exalted Niyati to the status of the motive factor of the universe and the sole agent of all phenomenal change. This is quite clear in our locus classicus, the Samaññaphala Sutta. Sin and suffering, attributed by other sects to the laws of karma, the result of evil committed in the previous lives or in the present one, were declared by Gosāla to be without cause or basis, other, presumably, than the force of destiny. Similarly, the escape from evil, the working off of accumulated evil karma, was likewise without cause or basis."

- ↑ 13.00 13.01 13.02 13.03 13.04 13.05 13.06 13.07 13.08 13.09 13.10 Dasti, Matthew R.; Bryant, Edwin F., eds (2014). "Just Another Word for Nothing Left to Lose: Freedom, Agency, and Ethics for Mādhyamikas". Free Will, Agency, and Selfhood in Indian Philosophy. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 172–185. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199922734.003.0008. ISBN 9780199395675. https://books.google.com/books?id=Ru0VDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA172.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Thakchoe, Sonam (Summer 2022). "The Theory of Two Truths in Tibet". in Zalta, Edward N.. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. The Metaphysics Research Lab, Center for the Study of Language and Information, Stanford University. OCLC 643092515. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/twotruths-tibet/. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ↑ Goldstein, Joseph. "Dependent Origination: The Twelve Links Explained" (in en). https://tricycle.org/magazine/dependent-origination/.

- ↑ David Kalupahana, Causality: The Central Philosophy of Buddhism. The University Press of Hawaii, 1975, page 78.

- ↑ Choong, Mun-keat (2000). The Fundamental Teachings of Early Buddhism: A Comparative Study Based on the Sutranga Portion of the Pali Samyutta-Nikaya and the Chinese Samyuktagama, pp. 192-197. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag.

- ↑ Choong, Mun-keat (2000). The Fundamental Teachings of Early Buddhism: A Comparative Study Based on the Sutranga Portion of the Pali Samyutta-Nikaya and the Chinese Samyuktagama, p. 192. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag.

- ↑ Kaccānagottasutta SN 12.15 SN ii 16, translated by Bhikkhu Sujato https://suttacentral.net/sn12.15/en/sujato

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Repetti, Ricardo (2012). "Buddhist Hard Determinism: No Self, No Free Will, No Responsibility". Journal of Buddhist Ethics 19: 136–137, 143–145. http://enlight.lib.ntu.edu.tw/FULLTEXT/JR-MAG/mag388415.pdf.

- ↑ Hoefer, Carl, "Causal Determinism", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2016 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- ↑ Barnes, E. J. (1984). The complete works of Aristotle, de interpretatione IX. princeton: Princeton University press.

- ↑ Zagzebski, Linda, "Foreknowledge and Free Will", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2017 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2017/entries/free-will-foreknowledge/>.

- ↑ Al-Farabi. (1981). Commentary on Aristotle's De Interpretatione. Translated by F.W.Zimmerman,. Oxford: Oxford university press.

- ↑ Origen Contra Celsum II 20

- ↑ Cicero De Fato 28-9

- ↑ Susanne Bobzien, Determinism and Freedom in Stoic Philosophy, Oxford 1998, chapter 5

- ↑ "Aristotle, De Interpretatione, 9". http://users.ox.ac.uk/~ball0888/salamis/interpretatione.html.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Mackie, Penelope. “Fatalism, Incompatibilism, and the Power To Do Otherwise” Noûs, vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 672-689, December 2003

- ↑ Whitaker, C. W.; Whitaker, C. W. A. (2002). Aristotle's De interpretatione: contradiction and dialectic. Oxford Aristotle studies. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-925419-4.

- ↑ Emery, Nina; Markosian, Ned; Sullivan, Meghan (2024), Zalta, Edward N.; Nodelman, Uri, eds., "Time", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2024/entriesime/, retrieved 2025-08-01

- ↑ Zalta, Edward N., ed (June 2, 2020). "Future Contingents". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/future-contingents/.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 "Ockhamism - Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy" (in en). https://www.rep.routledge.com/articles/thematic/ockhamism/v-1/sections/the-ockhamist-response-hard-and-soft-facts.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Andreoletti, Giacomo (2019). "Fatalism and Future Contingents" (in en). Analytic Philosophy 60 (3): 245–258. doi:10.1111/phib.12157. ISSN 2153-9596. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/phib.12157.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Ryerson, James (December 12, 2008). "Consider the Philosopher". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/14/magazine/14wwln-Wallace-t.html.

External links

- Fatalism vs. Free Will from Project Worldview

|

KSF

KSF