Golden Rule

Topic: Philosophy

From HandWiki - Reading time: 36 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 36 min

The ethic of reciprocity, also known colloquially as the Golden Rule, is the principle of treating others as one would want to be treated by them. It is sometimes called an ethics of reciprocity, meaning that one should reciprocate to others how one would like them to treat the person (not necessarily how they actually treat them). Various expressions of this rule can be found in the tenets of most religions and creeds through the ages.[1]

The maxim may appear as a positive or negative injunction governing conduct:

- Treat others as one would like others to treat them (positive or directive form)[1]

- Do not treat others in ways that one would not like to be treated (negative or prohibitive form)

- What one wishes upon others, they wish upon themselves (empathetic or responsive form)

Etymology

The term "Golden Rule", or "Golden law", began to be used widely in the early 17th century in Britain by Anglican theologians and preachers;[2] the earliest known usage is that of Anglicans Charles Gibbon and Thomas Jackson in 1604.[3]

Ancient history

Ancient Arabia

There’s substantial evidence that pre-Islamic Arab ethics contained principles similar to the Golden Rule, even if they weren’t formally codified like in later religious texts. The idea was embedded in tribal honor, poetry, and customary law (ʿurf).[citation needed]

Urf refers to the traditional customs and practices that were widely accepted and followed within Arab tribes. These customs were not codified in written laws but were deeply embedded in the social fabric and were passed down through generations. The adherence to ʿurf was considered essential for maintaining social harmony and tribal cohesion.[citation needed]

Antara Ibn Shaddad, a pre-Islamic poet, is quoted saying in his poetry “He who witnessed the battle informs you that I charge into combat and remain chaste at the spoils.”(Showing integrity—he does not take more than is rightfully his.),[4] whilst Imru Al-Qais is quoted saying "On that day I killed my riding camel for food for the maidens - How merry was their dividing my camel's trappings to be carried on their camels.."[5]

Key Aspects of ʿUrf

- Honor Codes (Sharaf and ʿIrd): Central to ʿurf were the concepts of sharaf (honor) for men and ʿird (honor) for women. These codes dictated behavior and were crucial in maintaining personal and familial dignity. Violations of these codes often led to severe repercussions, including blood feuds.[citation needed]

- Hospitality (Diyāfa): Hospitality was a sacred duty. Offering shelter and sustenance to guests, even if they were enemies, was a fundamental practice. This act was seen as a reflection of one's honor and generosity.[citation needed] Imruʾ al-Qays and other poets praised generosity and care toward travelers and guests.[4][5]

- Dispute Resolution: Tribal elders and leaders were responsible for mediating conflicts and disputes. The process often involved compensation (diya) or other forms of restitution. In some cases, trial by ordeal, such as the bisha'a (ordeal by fire), was used to determine guilt.[citation needed]

- Blood Feuds (Thar): The principle of thar emphasized the importance of avenging wrongs to restore honor. Failure to do so could lead to collective punishment of the tribe.[citation needed]

Ancient Egypt

Possibly the earliest affirmation of the maxim of reciprocity, reflecting the ancient Egyptian goddess Ma'at, appears in the story of "The Eloquent Peasant", which dates to the Middle Kingdom (c. 2040–1650 BCE): "Now this is the command: Do to the doer to make him do."[6][7]: 121 This proverb embodies the do ut des principle.[6] A Late Period (c. 664–323 BCE) papyrus contains an early negative affirmation of the Golden Rule: "That which you hate to be done to you, do not do to another."[8]

Ancient India

Sanskrit tradition

In Mahābhārata, the ancient epic of India, Vyasa says:[9]

Do not to others what you do not wish done to yourself; and wish for others too what you desire and long for for yourself–this is the whole of Dharma; heed it well

— Mahabharata, Anusasana Parva 113.8

The Mahābhārata is usually dated to the period between 400 BCE and 400 CE.[10][11]

Tamil tradition

In Chapter 32 in the Book of Virtue of the Tirukkuṛaḷ (c. 1st century BCE to 5th century CE), Valluvar says:

Do not do to others what you know has hurt yourself.

— Kural 316[12]

Why does one hurt others knowing what it is to be hurt?

— Kural 318[12]

Furthermore, in verse 312, Valluvar says that it is the determination or code of the spotless (virtuous) not to do evil, even in return, to those who have cherished enmity and done them evil. According to him, the proper punishment to those who have done evil is to put them to shame by showing them kindness, in return and to forget both the evil and the good done on both sides (verse 314).[13]

Ancient Greece

The Golden Rule in its prohibitive (negative) form was a common principle in ancient Greek philosophy. Examples of the general concept include:

- "Avoid doing what you would blame others for doing." – Thales[14] (c. 624 – c. 546 BCE)

- "What you do not want to happen to you, do not do it yourself either." – Sextus the Pythagorean.[15] The oldest extant reference to Sextus is by Origen in the third century of the common era.[16]

- "Ideally, no one should touch my property or tamper with it, unless I have given him some sort of permission, and, if I am sensible I shall treat the property of others with the same respect." – Plato[17] (c. 420 – c. 347 BCE)

- "Do not do to others that which angers you when they do it to you." – Isocrates[18] (436–338 BCE)

- "It is impossible to live a pleasant life without living wisely and well and justly, and it is impossible to live wisely and well and justly without living pleasantly." – Epicurus (341–270 BC) where "justly" refers to "an agreement made in reciprocal association ... against the infliction or suffering of harm."[19]

Ancient Persia

The Pahlavi Texts of Zoroastrianism (c. 300 BCE – 1000 CE) were an early source for the Golden Rule: "That nature alone is good which refrains from doing to another whatsoever is not good for itself." Dadestan-I-denig, 94,5, and "Whatever is disagreeable to yourself do not do unto others." Shayast-na-Shayast 13:29[20]

Ancient Rome

Seneca the Younger (c. 4 BCE – 65 CE), a practitioner of Stoicism (c. 300 BCE – 200 CE), expressed a hierarchical variation of the Golden Rule in his Letter 47, an essay regarding the treatment of slaves: "Treat your inferior as you would wish your superior to treat you."[21]

Religious context

According to Simon Blackburn, the Golden Rule "can be found in some form in almost every ethical tradition".[22] A multi-faith poster showing the Golden Rule in sacred writings from 13 faith traditions (designed by Paul McKenna of Scarboro Missions, 2000) has been on permanent display at the Headquarters of the United Nations since 4 January 2002.[23] Creating the poster "took five years of research that included consultations with experts in each of the 13 faith groups."[23] (See also the section on Global Ethic.)

Abrahamic religions

Judaism

A rule of reciprocal altruism was stated positively in a well-known Torah verse (Hebrew: ואהבת לרעך כמוך):

You shall not take vengeance or bear a grudge against your kinsfolk. Love your neighbor as yourself: I am the LORD.

— Leviticus 19:18[24]

According to John J. Collins of Yale Divinity School, most modern scholars, with Richard Elliott Friedman as a prominent exception, view the command as applicable to fellow Israelites.[25]

Rashi commented what constitutes revenge and grudge, using the example of two men. One man would not lend the other his ax, then the next day, the same man asks the other for his ax. If the second man should say, "'I will not lend it to you, just as you did not lend to me,' it constitutes revenge; if 'Here it is for you; I am not like you, who did not lend me,' it constitutes a grudge. Rashi concludes his commentary by quoting Rabbi Akiva on love of neighbor: 'This is a fundamental [all-inclusive] principle of the Torah.'"[26]

Hillel the Elder (c. 110 BCE – 10 CE)[27] used this verse as a most important message of the Torah for his teachings. Once, he was challenged by a gentile who asked to be converted under the condition that the Torah be explained to him while he stood on one foot. Hillel accepted him as a candidate for conversion to Judaism but, drawing on Leviticus 19:18, briefed the man:

What is hateful to you, do not do to your fellow: this is the whole Torah; the rest is the explanation; go and learn.

— Babylonian Talmud[28]

Hillel recognized brotherly love as the fundamental principle of Jewish ethics. Rabbi Akiva agreed, while Simeon ben Azzai suggested that the principle of love must have its foundation in Genesis chapter 1, which teaches that all men are the offspring of Adam, who was made in the image of God.[29][30] According to Jewish rabbinic literature, the first man Adam represents the unity of mankind. This is echoed in the modern preamble of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[31][32] It is also taught that Adam is last in order according to the evolutionary character of God's creation:[30]

Why was only a single specimen of man created first? To teach us that he who destroys a single soul destroys a whole world and that he who saves a single soul saves a whole world; furthermore, so no race or class may claim a nobler ancestry, saying, "Our father was born first"; and, finally, to give testimony to the greatness of the Lord, who caused the wonderful diversity of mankind to emanate from one type. And why was Adam created last of all beings? To teach him humility; for if he be overbearing, let him remember that the little fly preceded him in the order of creation.[30]

The Jewish Publication Society's edition of Leviticus states:

Thou shalt not hate thy brother, in thy heart; thou shalt surely rebuke thy neighbour, and not bear sin because of him. Thou shalt not take vengeance, nor bear any grudge against the children of thy people, but thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself: I am the LORD.[33]

This Torah verse represents one of several versions of the Golden Rule, which itself appears in various forms, positive and negative. It is the earliest written version of that concept in a positive form.[34]

At the turn of the era, the Jewish rabbis were discussing the scope of the meaning of Leviticus 19:18 and 19:34 extensively:

The stranger who resides with you shall be to you as one of your citizens; you shall love him as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt: I the LORD am your God.

— Leviticus 19:34[35]

Commentators interpret that this applies to foreigners (e.g. Samaritans), proselytes ('strangers who reside with you')[36] and Jews.[37]

On the verse, "Love your fellow as yourself", the classic commentator Rashi quotes from Torat Kohanim, an early Midrashic text regarding the famous dictum of Rabbi Akiva: "Love your fellow as yourself – Rabbi Akiva says this is a great principle of the Torah."[38]

In 1935, Rabbi Eliezer Berkovits explained in his work "What is the Talmud?" that Leviticus 19:34 disallowed xenophobia by Jews.[39]

Israel's postal service quoted from the previous Leviticus verse when it commemorated the Universal Declaration of Human Rights on a 1958 postage stamp.[40]

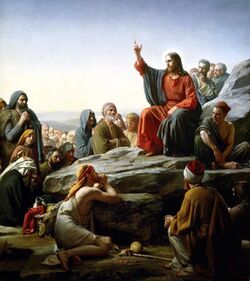

Christianity

New Testament

The Golden Rule was proclaimed by Jesus of Nazareth[41] during his Sermon on the Mount and described by him as the second great commandment. The common English phrasing is "Do unto others as you would have them do unto you". Various applications of the Golden Rule are stated positively numerous times in the Old Testament: "You shall not take vengeance or bear a grudge against any of your people, but you shall love your neighbor as yourself: I am the LORD."[42] Or, in Leviticus 19:34: "The alien who resides with you shall be to you as the native-born among you; you shall love the alien as yourself, for you were aliens in the land of Egypt: I am the LORD your God."[42] These two examples are given in the Septuagint as follows: "And thy hand shall not avenge thee; and thou shalt not be angry with the children of thy people; and thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself; I am the Lord." and "The stranger that comes to you shall be among you as the native, and thou shalt love him as thyself; for ye were strangers in the land of Egypt: I am the Lord your God."[43]

Two passages in the New Testament quote Jesus of Nazareth espousing the positive form of the Golden rule:[44]

"In everything do to others as you would have them do to you, for this is the Law and the Prophets."

— Matthew 7:12, New Revised Standard Version, Updated Edition (NRSVUE)

Do to others as you would have them do to you.

— Luke 6:31, New Revised Standard Version, Updated Edition (NRSVUE)

A similar passage, a parallel to the Great Commandment, is to be found later in the Gospel of Luke.[45]

An expert in the law stood up to test him [Jesus]. "Teacher," he said, "what must I do to inherit eternal life?"

He said to him, "What is written in the law? What do you read there?"

He answered, "You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind and your neighbor as yourself."

And he said to him, "You have given the right answer; do this, and you will live."

— Luke 10:25–28, New Revised Standard Version, Updated Edition (NRSVUE)

The passage in the book of Luke then continues with Jesus answering the question, "Who is my neighbor?", by telling the parable of the Good Samaritan, which John Wesley interprets as meaning that "your neighbor" is anyone in need.[46]

Jesus' teaching goes beyond the negative formulation of not doing what one would not like done to themselves, to the positive formulation of actively doing good to another that, if the situations were reversed, one would desire that the other would do for them. This formulation, as indicated in the parable of the Good Samaritan, emphasizes the needs for positive action that brings benefit to another, not simply restraining oneself from negative activities that hurt another.[47]

In one passage of the New Testament, Paul the Apostle refers to the golden rule, restating Jesus' second commandment:[48]

For the whole law is summed up in a single commandment, "You shall love your neighbor as yourself."

— Galatians 5:14, New Revised Standard Version, Updated Edition (NRSVUE)

St. Paul also comments on the golden rule in the Epistle to the Romans:[49]

Owe no one anything, except to love one another, for the one who loves another has fulfilled the law.

The commandments, "You shall not commit adultery; you shall not murder; you shall not steal; you shall not covet," and any other commandment, are summed up in this word, "You shall love your neighbor as yourself."

— Romans 13:8–9, New Revised Standard Version, Updated Edition (NRSVUE)

Deuterocanon

The Old Testament Deuterocanonical books of Tobit and Sirach, accepted as part of the Scriptural canon by Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodoxy, and the non-Chalcedonian churches, express a negative form of the golden rule:[50][51]

And what you hate, do not do to anyone. May no evil go with you on any of your way.

— Tobit 4:15, New Revised Standard Version, Updated Edition (NRSVUE)

Judge your neighbor’s feelings by your own, and in every matter be thoughtful.

— Sirach 31:15, New Revised Standard Version, Updated Edition (NRSVUE)

Church Fathers

Early Christian authors wrote on the Golden Rule.[52] The early Christian treatise the Didache included the Golden Rule in saying "in everything, do not do to another what you would not want done to you."[53]

Clement of Alexandria, commenting on the Golden Rule in Luke 6:31, calls the concept "all embracing" for how one acts in life.[54] Clement further pointed to the phrasing in the book of Tobit as part of the ethics between husbands and wives. Tertullian stated that the rule taught "love, respect, consolation, protection, and benefits".[55]

While many Church Fathers framed the Golden Rule as part of Jewish and Christian Ethics, Theophilus of Antioch stated that it had universal application for all of humanity.[56] Origen connected the Golden Rule with the law written on the hearts of Gentiles mentioned by Paul in his letter to the Romans, and had universal application to Christian and non-Christian alike.[57]

Basil of Caesarea commented that the negative form of the Golden Rule was for avoiding evil while the positive form was for doing good.[58]

Islam

The Arabian peninsula was said to not practice the golden rule prior to the advent of Islam.[according to whom?] However, in some instances it is clear that the pre-Islamic Arabs, did to some extent understand the Golden Rule, such as after the Battle of Autas where the companions of Mohammed refused to have intercourse with married women taken as captives before a verse allowing them to do so was revealed,[59] they would also not take bounties/spoils of war as Antara Ibn Shaddad is quoted saying in his poetry “He who witnessed the battle informs you that I charge into combat and remain chaste at the spoils.”(Showing integrity—he does not take more than is rightfully his.),[4] which Mohammed allowed for himself,[60] furthermore, Imru' Al-Qays (pre-Islamic poet) emphasizes similarly in his poetry,[5] reflecting an early form of the Golden Rule.

According to Th. Emil Homerin: "Pre-Islamic Arabs regarded the survival of the tribe, as most essential and to be ensured by the ancient rite of blood vengeance."[61] Homerin goes on to say:

Similar examples of the golden rule are found in the hadiths. The hadith recount what the prophet is claimed to have said and done, and generally Muslims regard the hadith as second to only the Qur'an as a guide to correct belief and action.[62]

From the hadith:

A Bedouin came to the prophet, grabbed the stirrup of his camel and said: O the messenger of God! Teach me something to go to heaven with it. Prophet said: "As you would have people do to you, do to them; and what you dislike to be done to you, don't do to them. Now let the stirrup go! [This maxim is enough for you; go and act in accordance with it!]"

— Kitab al-Kafi, Volume 2, Book 1, Chapter 66:10[63] (Shia source)

None of you [truly] believes until he wishes for his brother what he wishes for himself.

— An-Nawawi's Forty Hadith 13 (p. 56)[64] (Sunni source)

Seek for mankind that of which you are desirous for yourself, that you may be a believer.

— Sukhanan-i-Muhammad (Teheran, 1938)[65] (Shia source)

That which you want for yourself, seek for mankind.[65]

The most righteous person is the one who consents for other people what he consents for himself, and who dislikes for them what he dislikes for himself.[65]

Ali ibn Abi Talib (4th Caliph in Sunni Islam, and first Imam in Shia Islam) says:

O my child, make yourself the measure (for dealings) between you and others. Thus, you should desire for others what you desire for yourself and hate for others what you hate for yourself. Do not oppress as you do not like to be oppressed. Do good to others as you would like good to be done to you. Regard bad for yourself whatever you regard bad for others. Accept that (treatment) from others which you would like others to accept from you ... Do not say to others what you do not like to be said to you.

— Nahjul Balaghah, Letter 31[66]

Muslim scholar Al-Qurtubi looked at the Golden Rule of loving one's neighbor and treating them as one wishes to be treated as having universal application to believers and unbelievers alike.[67] Relying upon a Hadith, exegist Ibn Kathir listed those "who judge people the way they judge themselves" as people who will be among the first to be Resurrected.[68]

Hussein bin Ali bin Awn al-Hashemi (102nd Caliph in Sunni Islam), repeated the Golden Rule in the context of the Armenian genocide, thus, in 1917, he states:[69]

Winter is ahead of us. Refugees from the Armenian Jacobite Community will probably need warmth. Help them how you would help your brothers. Pray for these people who have been expelled from their homes and left homeless and devoid of livestock and all their property.

Mandaeism

In Mandaean scriptures, the Ginza Rabba and Mandaean Book of John contain a prohibitive form of the Golden Rule that is virtually identical to the one used by Hillel.

ia mhaimnia u-šalmania kul ḏ-īlauaikun snia b-habraikun la-tibdun |

O you believers and perfect ones! All that is hateful to you – do not do it to your neighbours. |

| —Mandaic transliteration | —Right Ginza Book 1, section 150, p. 32 (Gelbert 2011)[70] |

O you perfect and faithful ones! Everything that is hateful and detestable to you – do not do it to your neighbours. Everything that seems good to you – do it if you are capable of doing it, and support each other.

— Right Ginza Book 2, section 65, p. 51 (Gelbert 2011)[70]

My sons! Everything that is hateful to you, do not do it to thy comrade, for in the world to which you are going, there is a judgment and a great summing up.

— Mandaean Book of John Chapter 47, section 13, pp. 117–8 (Gelbert 2017)[71]

Baháʼí Faith

The writings of the Baháʼí Faith encourage everyone to treat others as they would treat themselves and even prefer others over oneself:

O SON OF MAN! Deny not My servant should he ask anything from thee, for his face is My face; be then abashed before Me.

Blessed is he who preferreth his brother before himself.

And if thine eyes be turned towards justice, choose thou for thy neighbour that which thou choosest for thyself.

Ascribe not to any soul that which thou wouldst not have ascribed to thee, and say not that which thou doest not.

Indian religions

Hinduism

One should never do that to another which one regards as injurious to one's own self. This, in brief, is the rule of dharma. Other behavior is due to selfish desires.

— Brihaspati, Mahabharata 13.113.8 (Critical edition)[80]

By making dharma your main focus, treat others as you treat yourself[81]

Also,

श्रूयतां धर्मसर्वस्वं श्रुत्वा चाप्यवधार्यताम्।

आत्मनः प्रतिकूलानि परेषां न समाचरेत्।।If the entire Dharma can be said in a few words, then it is—that which is unfavorable to us, do not do that to others.

— Padmapuraana, shrushti 19/357–358

Buddhism

Buddha (Siddhartha Gautama, c. 623–543 BCE)[82][83] made the negative formulation of the golden rule one of the cornerstones of his ethics in the 6th century BCE. It occurs in many places and in many forms throughout the Tripitaka.

Comparing oneself to others in such terms as "Just as I am so are they, just as they are so am I," he should neither kill nor cause others to kill.

— Sutta Nipata 705

One who, while himself seeking happiness, oppresses with violence other beings who also desire happiness, will not attain happiness hereafter.

— Dhammapada 10. Violence

Hurt not others in ways that you yourself would find hurtful.

— Udanavarga 5:18

Putting oneself in the place of another, one should not kill nor cause another to kill.[84]

Jainism

The Golden Rule is paramount in the Jainist philosophy and can be seen in the doctrines of ahimsa and karma. As part of the prohibition of causing any living beings to suffer, Jainism forbids inflicting upon others what is harmful to oneself.

The following line from the Acaranga Sutra sums up the philosophy of Jainism:

Nothing which breathes, which exists, which lives, or which has essence or potential of life, should be destroyed or ruled over, or subjugated, or harmed, or denied of its essence or potential. In support of this Truth, I ask you a question – "Is sorrow or pain desirable to you?" If you say "yes it is", it would be a lie. If you say, "No, It is not" you will be expressing the truth. Just as sorrow or pain is not desirable to you, so it is to all which breathe, exist, live or have any essence of life. To you and all, it is undesirable, and painful, and repugnant.[85]

A man should wander about treating all creatures as he himself would be treated.

— Sutrakritanga, 1.11.33

In happiness and suffering, in joy and grief, we should regard all creatures as we regard our own self.

— Lord Mahavira, 24th Tirthankara

Sikhism

Precious like jewels are the minds of all. To hurt them is not at all good. If thou desirest thy Beloved, then hurt thou not anyone's heart.

— Guru Arjan Dev Ji 259, Guru Granth Sahib

Chinese religions

Confucianism

己所不欲,勿施於人。 |

What you do not wish for yourself, do not do to others. |

{{verse translation|lang=zh|italicsoff=y|子貢問曰:「有一言而可以終身行之者乎?」

子曰:「其恕乎!己所不欲,勿施於人。」

|Zi Gong [a disciple of Confucius] asked: "Is there any one word that could guide a person throughout life?"

The Master replied: "How about 'shu' [reciprocity]: never impose on others what you would not choose for yourself?"

The same idea is also presented in V.12 and VI.30 of the Analects (c. 500 BCE), which can be found in the online Chinese Text Project. The phraseology differs from the Christian version of the Golden Rule. It does not presume to do anything unto others, but merely to avoid doing what would be harmful. It does not preclude doing good deeds and taking moral positions.

In relation to the Golden Rule, Confucian philosopher Mencius said "If one acts with a vigorous effort at the law of reciprocity, when he seeks for the realization of perfect virtue, nothing can be closer than his approximation to it."[86]

Taoism

The sage has no interest of his own, but takes the interests of the people as his own. He is kind to the kind; he is also kind to the unkind: for Virtue is kind. He is faithful to the faithful; he is also faithful to the unfaithful: for Virtue is faithful.

— Tao Te Ching, Chapter 49

Regard your neighbor's gain as your own gain, and your neighbor's loss as your own loss.

Mohism

If people regarded other people's states in the same way that they regard their own, who then would incite their own state to attack that of another? For one would do for others as one would do for oneself. If people regarded other people's cities in the same way that they regard their own, who then would incite their own city to attack that of another? For one would do for others as one would do for oneself. If people regarded other people's families in the same way that they regard their own, who then would incite their own family to attack that of another? For one would do for others as one would do for oneself. And so if states and cities do not attack one another and families do not wreak havoc upon and steal from one another, would this be a harm to the world or a benefit? Of course one must say it is a benefit to the world.

Mozi regarded the Golden Rule as a corollary to the cardinal virtue of impartiality, and encouraged egalitarianism and selflessness in relationships.

Iranian religions

Zoroastrianism

Do not do unto others whatever is injurious to yourself.

— Shayast-na-Shayast 13.29

New religious movements

Wicca

Hear ye these words and heed them well, the words of Dea, thy Mother Goddess, "I command thee thus, O children of the Earth, that that which ye deem harmful unto thyself, the very same shall ye be forbidden from doing unto another, for violence and hatred give rise to the same. My command is thus, that ye shall return all violence and hatred with peacefulness and love, for my Law is love unto all things. Only through love shall ye have peace; yea and verily, only peace and love will cure the world, and subdue all evil."

— The Book of Ways, Devotional Wicca

Scientology

Try not to do things to others that you would not like them to do to you.

Try to treat others as you would want them to treat you.

Traditional African religions

Yoruba

One who is going to take a pointed stick to pinch a baby bird should first try it on himself to feel how it hurts.

— Yoruba Proverb

Odinani

egbe bere ugo bere nke si ibeya ebela nku kwaya |

let the hawk perch, let the eagle perch, whichever says the other should not perch, let its wings be broken |

| —Igbo proverb[89] |

Secular context

Global ethic

The "Declaration Toward a Global Ethic"[90] from the Parliament of the World's Religions (1993) proclaimed the Golden Rule ("We must treat others as we wish others to treat us") as the common principle for many religions.[91] The Initial Declaration was signed by 143 leaders from all of the world's major faiths, including Baháʼí Faith, Brahmanism, Brahma Kumaris, Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Indigenous, Interfaith, Islam, Jainism, Judaism, Native American, Neo-Pagan, Sikhism, Taoism, Theosophist, Unitarian Universalist and Zoroastrian.[91][92]

Humanism

In the view of Greg M. Epstein, a Humanist chaplain at Harvard University, "'do unto others' ... is a concept that essentially no religion misses entirely. But not a single one of these versions of the golden rule requires a God."[93] Various sources identify the Golden Rule as a humanist principle:[94]

Trying to live according to the Golden Rule means trying to empathise with other people, including those who may be very different from us. Empathy is at the root of kindness, compassion, understanding and respect – qualities that we all appreciate being shown, whoever we are, whatever we think and wherever we come from. And although it isn't possible to know what it really feels like to be a different person or live in different circumstances and have different life experiences, it isn't difficult for most of us to imagine what would cause us suffering and to try to avoid causing suffering to others. For this reason many people find the Golden Rule's corollary – "do not treat people in a way you would not wish to be treated yourself" – more pragmatic.[94]

— Maria MacLachlan, Think Humanism[95][failed verification]

Do not do to others what you would not want them to do to you. ... [is] the single greatest, simplest, and most important moral axiom humanity has ever invented, one which reappears in the writings of almost every culture and religion throughout history, the one we know as the Golden Rule. Moral directives do not need to be complex or obscure to be worthwhile, and in fact, it is precisely this rule's simplicity which makes it great. It is easy to come up with, easy to understand, and easy to apply, and these three things are the hallmarks of a strong and healthy moral system. The idea behind it is readily graspable: before performing an action which might harm another person, try to imagine yourself in their position, and consider whether you would want to be the recipient of that action. If you would not want to be in such a position, the other person probably would not either, and so you should not do it. It is the basic and fundamental human trait of empathy, the ability to vicariously experience how another is feeling, that makes this possible, and it is the principle of empathy by which we should live our lives.

— Adam Lee, Ebon Musings, "A decalogue for the modern world"[96]

Existentialism

When we say that man chooses for himself, we do mean that every one of us must choose himself; but by that we also mean that in choosing for himself he chooses for all men. For in effect, of all the actions a man may take in order to create himself as he wills to be, there is not one which is not creative, at the same time, of an image of man such as he believes he ought to be. To choose between this or that is at the same time to affirm the value of that which is chosen; for we are unable ever to choose the worse. What we choose is always the better; and nothing can be better for us unless it is better for all.

— Jean-Paul Sartre, Existentialism is a Humanism, pp. 291–292[97]

Classical Utilitarianism

John Stuart Mill in his book, Utilitarianism (originally published in 1861), wrote, "In the golden rule of Jesus of Nazareth, we read the complete spirit of the ethics of utility. 'To do as you would be done by,' and 'to love your neighbour as yourself,' constitute the ideal perfection of utilitarian morality."[98]

Other contexts

Human rights

According to Marc H. Bornstein, and William E. Paden, the Golden Rule is arguably the most essential basis for the modern concept of human rights, in which each individual has a right to just treatment, and a reciprocal responsibility to ensure justice for others.[99]

However, Leo Damrosch argued that the notion that the Golden Rule pertains to "rights" per se is a contemporary interpretation and has nothing to do with its origin. The development of human "rights" is a modern political ideal that began as a philosophical concept promulgated through the philosophy of Jean Jacques Rousseau in 18th century France, among others. His writings influenced Thomas Jefferson, who then incorporated Rousseau's reference to "inalienable rights" into the United States Declaration of Independence in 1776. Damrosch argued that to confuse the Golden Rule with human rights is to apply contemporary thinking to ancient concepts.[100]

Variations

The Platinum Rule has been said to be stated as, "Do to others as they would have you do to them." Taken in the spirit of the Golden Rule, this suggests one should be familiar or at least consider the desires of the person they're interacting with.[101] However, this is the flaw of the rule in that it requires one to stereotype or make broad assumptions about a stranger's interests and personality before interacting with them. These kind of assumptions are often erroneous and therefore a prudent person would avoid the interaction knowing their assumptions are likely incorrect. This rule is prohibitive to communication and prefers no interaction over any interaction with strangers. On occasion, stereotypes may be applied and in rare cases are largely correct. In those situations this rule can be applied successfully.

On the other hand, the Platinum Rule is broadly successful when interacting with familiar people and directs that all interaction be conducted in a manner the person would like to be treated. This demonstrates respect and the desire to favorably regard the person one is interacting with. Unfortunately, this can lead to a dependent relationship, developing a psychological tendency to expect similar treatment in all relationships and avoid forming new relationships where this treatment would not exist simply from not knowing the individuals preferences.

Despite the unusual cases stifling interaction or individuals developing a demand for this behavior from others, the Platinum Rule requires due consideration, self-control, and receiver analysis. Taken altogether, the Platinum Rule represents a gesture of kindness, and is an established norm in various industries, such as marketing, medical care, motivational speaking, and many others.[102] As a consequence, some argue the Golden Rule is outdated, self-absorbed, and grossly fails to consider the needs of others.[103][104]

Science and economics

Some published research argues that some 'sense' of fair play and the Golden Rule may be stated and rooted in terms of neuroscientific and neuroethical principles.[105]

The Golden Rule can also be explained from the perspectives of psychology, philosophy, sociology, human evolution, and economics. Psychologically, it involves a person empathizing with others. Philosophically, it involves a person perceiving their neighbor also as "I" or "self".[106] Sociologically, "love your neighbor as yourself" is applicable between individuals, between groups, and also between individuals and groups. In evolution, "reciprocal altruism" is seen as a distinctive advance in the capacity of human groups to survive and reproduce, as their exceptional brains demanded exceptionally long childhoods and ongoing provision and protection even beyond that of the immediate family.[107] In economics, Richard Swift, referring to ideas from David Graeber, suggests that "without some kind of reciprocity society would no longer be able to exist."[108]

Study of other primates provides evidence that the Golden Rule exists in other non-human species.[109]

Criticism

Philosophers such as Immanuel Kant[110] and Friedrich Nietzsche[111] have objected to the rule on a variety of grounds. One is the epistemic question of determining how others want to be treated. The obvious way is to ask them, but they might give duplicitous answers if they find this strategically useful, and they might also fail to understand the details of the choice situation as one understands it. People might also be biased to perceiving harms and benefits to themselves more than to others, which could lead to escalating conflict if they are suspicious of others. Hence Linus Pauling suggested that a bias towards others is to be introduced into the golden rule: "Do unto others 20 percent better than you would have them do unto you" - to correct for subjective bias.[112]

Differences in values or interests

George Bernard Shaw wrote, "Do not do unto others as you would that they should do unto you. Their tastes may not be the same."[113] This suggests that if one's values are not shared with others, the way one wants to be treated will not be the way others want to be treated. Hence, the Golden Rule of "do unto others" is "dangerous in the wrong hands",[114] according to philosopher Iain King, because "some fanatics have no aversion to death: the Golden Rule might inspire them to kill others in suicide missions."[114]

Walter Terence Stace, in The Concept of Morals (1937) argued that Shaw's remark

...seems to overlook the fact that "doing as you would be done by" includes taking into account your neighbour's tastes as you would that he should take yours into account. Thus the "golden rule" might still express the essence of a universal morality even if no two men in the world had any needs or tastes in common.[115]

Differences in situations

Immanuel Kant famously criticized the golden rule for not being sensitive to differences of situation, noting that a prisoner duly convicted of a crime could appeal to the golden rule while asking the judge to release him, pointing out that the judge would not want anyone else to send him to prison, so he should not do so to others.[110] On the other hand, in a critique of the consistency of Kant's writings, several authors have noted the similarity[116] between the Golden Rule and Kant's concept of the categorical imperative.

This was perhaps a well-known objection, as Leibniz actually responded to it long before Kant made it, suggesting that the judge should put himself in the place, not merely of the criminal, but of all affected persons and then judging each option (to inflict punishment, or release the criminal, etc.) by whether there was a “greater good in which this lesser evil was included.”[117]

Other responses to criticisms

Marcus George Singer observed that there are two importantly different ways of looking at the golden rule: as requiring either that one performs specific actions that they want others to do to them or that they guide their behavior in the same general ways that they want others to.[118] Counter-examples to the Golden Rule typically are more forceful against the first than the second.

In his book on the Golden Rule, Jeffrey Wattles makes the similar observation that such objections typically arise while applying the Golden Rule in certain general ways (namely, ignoring differences in taste or situation, failing to compensate for subjective bias, etc.) But if people apply the golden rule to their own method of using it, asking in effect if they would want other people to apply the Golden Rule in such ways, the answer would typically be no, since others' ignoring of such factors will lead to behavior which people object to. It follows that people should not do so themselves—according to the Golden Rule. In this way, the Golden Rule may be self-correcting.[119] An article by Jouni Reinikainen develops this suggestion in greater detail.[120]

It is possible, then, that the golden rule can itself guide people in identifying which differences of situation are morally relevant. People would often want other people to ignore any prejudice against their race or nationality when deciding how to act towards them, but would also want others to not ignore their differing preferences in food, desire for aggressiveness, and so on. This principle of "doing unto others, wherever possible, as they would be done by..." has sometimes been termed the Platinum Rule.[121]

Popular references

Charles Kingsley's The Water Babies (1863) includes a character named Mrs Do-As-You-Would-Be-Done-By (and another, Mrs Be-Done-By-As-You-Did).[122]

See also

- Empathy

- Eye for an eye

- General welfare clause

- Kali's morality - a literary example of character not using the Golden Rule

- Norm of reciprocity, social norm of in-kind responses to the behavior of others

- Reciprocity (cultural anthropology), way of defining people's informal exchange of goods and labour

- Reciprocity (evolution), mechanisms for the evolution of cooperation

- Reciprocity (international relations), principle that favours, benefits, or penalties that are granted by one state to the citizens or legal entities of another, should be returned in kind

- Reciprocity (social and political philosophy), concept of reciprocity as in-kind positive or negative responses for the actions of others; relation to justice; related ideas such as gratitude, mutuality, and the Golden Rule

- Reciprocity (social psychology), in-kind positive or negative responses of individuals towards the actions of others

- Serial reciprocity, where the benefactor of a gift or service will in turn provide benefits to a third party

- Ubuntu, an ethical philosophy originating from Southern Africa, which has been summarised as 'A person is a person through other people'

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Antony Flew, ed (1979). "golden rule". A Dictionary of Philosophy. London: Pan Books in association with The MacMillan Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-330-48730-6.

- ↑ Thomas Jackson: First Sermon upon Matthew 7,12 (1615; Werke Band 3, S. 612); Benjamin Camfield: The Comprehensive Rule of Righteousness (1671); George Boraston: The Royal Law, or the Golden Rule of Justice and Charity (1683); John Goodman: The Golden Rule, or, the Royal Law of Equity explained (1688; Titelseite als Faksimile at Google Books); dazu Olivier du Roy: The Golden Rule as the Law of Nature. In: Jacob Neusner, Bruce Chilton (Hrsg.): The Golden Rule – The Ethics of Reprocity in World Religions. London/New York 2008, S. 94.

- ↑ Gensler, Harry J. (2013). Ethics and the Golden Rule. Routledge. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-415-80686-2.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Antarah ibn Shaddad. *Diwan: Pre-Islamic Era*. “هل غادر الشعراء من متردم.” Arabic: يُخبِركِ مَن شَهِدَ الوَقيعَةَ أَنَّني أَغشى الوَغى وَأَعِفُّ عِندَ المَغنَمِ Transliteration: Yukhbiruki man shahida al-waqi‘ah anni aghsha al-waghā wa a‘iffu ‘inda al-maghnam English translation: “He who witnessed the battle informs you that I charge into combat and remain chaste at the spoils.”

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Archive, Internet Sacred Text. "The Poem of Imru-ul-Quais | Sacred Texts Archive" (in English). https://sacred-texts.com/isl/hanged/hanged1.htm. "فَذَبحْتُ جَملِي لِيَومِ الوَفَادَةِ فَسَعِدَ النِّسَاءُ فِي تَقْسِيمِ زِيّهِ لِيَحْمِلْنَ أَحْوَائِهُ عَلَى جِمَالِهِنَّ"

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Eloquent Peasant". 25 September 2015. http://www.usc.edu/dept/LAS/wsrp/information/REL499_2011/Eloquent%20Peasant.pdf.

- ↑ Wilson, John A.. The Culture of Ancient Egypt. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-90152-1.

- ↑ Jasnow, Richard (1992). A Late Period Hieratic Wisdom Text. Chicago, Ill: Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-918986-85-6. http://oi.uchicago.edu/pdf/saoc52.pdf. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ↑ Swidler, Leonard J.; Mojzes, Paul (2000) (in en). The Study of Religion in an Age of Global Dialogue. Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-56639-793-3. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Study_of_Religion_in_an_Age_of_Globa/rBZHSKLmniAC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Mah%C4%81bh%C4%81rata+golden+rule&pg=PA183&printsec=frontcover.

- ↑ Cush, D., Robinson, C., York, M. (eds.) (2008) "Mahābhārata" in Encyclopedia of Hinduism . Abingdon: Routledge, p 469

- ↑ van Buitenen, J.A.B. (1973) The Mahābhārata, Book 1: The Book of the Beginning . Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press, p xxv

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Sundaram, P. S. (1990). Tiruvalluvar Kural. Gurgaon: Penguin. pp. 50. ISBN 978-0-14-400009-8.

- ↑ Aiyar, V. V. S. (2007). The Kural or the Maxims of Tiruvalluvar (1 ed.). Chennai: Pavai. pp. 141–142. ISBN 978-81-7735-262-7.

- ↑ Diogenes Laërtius, "The Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers", I:36

- ↑ "The Sentences of Sextus -- The Nag Hammadi Library". http://www.gnosis.org/naghamm/sent.html.

- ↑ The Sentences of Sextus Article

- ↑ Plato, Laws, Book XI (Complete Works of Plato, 1997 edited Cooper ISBN 978-0-87220-349-5)

- ↑ Isocrates, Nicocles or the Cyprians, Isoc 3.61 (original text in Greek); cf. Isoc. 1.14 , Isoc. 2.24, 38 , Isoc. 4.81 .

- ↑ "Principal Doctrines 5 and 33" , Principal Doctrines by Epicurus, Translated by Robert Drew Hicks, The Internet Classics Archive, MIT.

- ↑ Thomas Firminger Thiselton-Dyer (2008). Pahlavi Texts of Zoroastrianism, Part 2 of 5: The Dadistan-i Dinik and the Epistles of Manuskihar. Forgotten Books. ISBN 978-1-60620-199-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=XdYYnfBXh9QC. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ↑ Lucius Annaeus Seneca (1968). The Stoic Philosophy of Seneca: Essays and Letters of Seneca. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-00459-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=e6pvK6SQuvgC. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ↑ Blackburn, Simon (2001). Ethics: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-19-280442-6.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Mezei, Leslie (May 2002). "The Golden Rule Poster - A History: Multi-faith Sacred Writings and Symbols from 13 Traditions". Spiritan Missionary News / Scarboro Missions. https://www.scarboromissions.ca/golden-rule/the-golden-rule-poster-a-history.

- ↑ Bible, Leviticus 19:18

- ↑ Collins, John (April 27, 2020). "Love Your Neighbor: How It Became the Golden Rule". https://www.thetorah.com/article/love-your-neighbor-how-it-became-the-golden-rule.

- ↑ "Chabad: Leviticus 19:18". https://www.chabad.org/library/bible_cdo/aid/9920/showrashi/true/jewish/Chapter-19.htm#lt=primary.

- ↑ "Hillel". Jewish Encyclopedia. . "His activity of forty years is perhaps historical; and since it began, according to a trustworthy tradition (Shab. 15a), one hundred years before the destruction of Jerusalem, it must have covered the period 30 BCE – 10 CE."

- ↑ Shabbath folio:31a

- ↑ (Sifra, Ḳedoshim, iv.; Yer. Ned. ix. 41c; Genesis Rabba 24

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 "ADAM". Jewish Encyclopedia. http://jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=758&letter=A&search=adam#1. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ↑ "Mishnah Seder Nezikin Sanhedrin 4.5". sefaria.org. http://www.sefaria.org/Mishnah_Sanhedrin.4?lang=en.

- ↑ "Tosefta on Mishnah Seder Nezikin Sanhedrin 8.4–9 (Erfurt Manuscript)". toseftaonline.org. 2012-08-21. http://www.toseftaonline.org/Tractate-Sanhedrin-chapter-8-tosefta-4.

- ↑ "Leviticus". The Torah. Jewish Publication Society. p. 19:17. http://www.sacred-texts.com/bib/jps/lev019.htm. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ↑ Plaut, The Torah – A Modern Commentary; Union of American Hebrew Congregations, New York 1981; p. 892.

- ↑ Bible, Leviticus 19:34

- ↑ Rabbi Akiva, bQuid 75b

- ↑ Rabbi Gamaliel, yKet 3, 1; 27a

- ↑ Kedoshim 19:18, Toras Kohanim, ibid. See also Talmud Yerushalmi, Nedarim 9:4; Bereishis Rabbah 24:7.

- ↑ Eliezer Berkovits (1935). What is the Talmud. VIII What is not written in the Talmud? Jew and Gentile, 4 Xenophobia?, 3

- ↑ "Sol Singer Collection of Philatelic Judaica". Emory University. http://marbl.library.emory.edu/DigitalExhibits/stamps/015.html.

- ↑ Matthew 7:12; see also Luke 6:31

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 "Bible Gateway passage: Leviticus 19 - New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition" (in en). https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Leviticus%2019&version=NRSVUE.

- ↑ "Brenton Septuagint Translation Leviticus 19". https://ebible.org/eng-Brenton/LEV19.htm.

- ↑ "Matthew 7 - New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition" (in en). https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Matthew%207&version=NRSVUE.

- ↑ "Bible Gateway passage: Luke 10 – New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition" (in en). https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Luke%2010&version=NRSVUE.

- ↑ "John Wesley's Explanatory Notes on Luke 10". Christnotes.org. http://www.christnotes.org/commentary.php?b=42&c=10&com=wes.

- ↑ Moore, Judaism in the First Centuries of the Christian Era, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1927–1930; Vol. 2, p. 87, Vol. 3, p. 180.

- ↑ "Galatians 5 - New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition" (in en). https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Galatians%205&version=NRSVUE.

- ↑ "Bible Gateway passage: Romans 13 - New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition" (in en). https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Romans%2013&version=NRSVUE.

- ↑ "Tobit 4 - New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition" (in en). https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Tobit%204&version=NRSVUE.

- ↑ "Bible Gateway passage: Sirach 31 - New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition" (in en). https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Sirach%2031&version=NRSVUE.

- ↑ Steenbuch, Johannes Aakjær (2019). "The problem of the negative version of the Golden Rule in early Christian ethics". PNA (34). https://www.academia.edu/download/63283979/21486-Artikeltext-52254-1-10-2020032120200512-1296-ey3jsr.pdf.

- ↑ Didache 1.2, in: Bart D. Ehrman, The Apostolic Fathers: Volume I. I Clement. II Clement. Ignatius. Polycarp. Didache. Barnabas, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003

- ↑ Clement of Alexandria, Paedagogus 3.12.88.1

- ↑ Tertullian, Adversus Marcionem 4.16

- ↑ Theophilus, Ad Autolycum 2.34

- ↑ Origen, Commentaria in Epistolam B. Pauli ad Romanos 2.9.9

- ↑ Basil of Caesarea, In Hexaemeron 9.3

- ↑ Template:CiteHadith (Sunni Hadith) Bihar al-Anwar – Allama al-Majlisi – Vol. 100 – Page 339 (Shia Exegesis)

- ↑ Quran, 8:41 Hadith, Template:CiteHadith

- ↑ Th. Emil Homerin (2008). Neusner, Jacob. ed. The Golden Rule: The Ethics of Reciprocity in World Religions. Bloomsbury. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-4411-9012-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=b3ISBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA99. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ↑ Th. Emil Homerin (2008). Neusner, Jacob. ed. The Golden Rule: The Ethics of Reciprocity in World Religions. Bloomsbury. p. p. 102. ISBN 978-1-4411-9012-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=b3ISBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA99. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ↑ Kitab al-Kafi. https://thaqalayn.net/hadith/2/1/66/10. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ↑ Wattles (191), Rost (100)

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 "Sukhanan-i-Muhammad" [Conversations of Muhammad], Wattles (192); Rost (100); Donaldson Dwight M. (1963). Studies in Muslim Ethics, p. 82. London: S.P.C.K.

- ↑ Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥusayn Sharīf al-Raḍī and ʻAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib (eds.), Nahj Al-balāghah: Selection from Sermons, Letters and Sayings of Amir Al-Muʼminin, Volume 2. Translated by Syed Ali Raza. Ansariyan. ISBN 978-9644383816 p. 350

- ↑ Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad Qurṭubī, Jamiʻ li-Aḥkām al-Qurʼan (al-Qāhirah: Dār al-Kutūb alMiṣrīyah, 1964), 5:184

- ↑ Ismā’īl ibn ’Umar ibn Kathīr, Tafsīr al-Qurān al-‘Aẓīm (Bayrūt: Dār al-Kutub al-ʻIlmīyah, 1998), 8:6

- ↑ Avetisyan, Vigen (2019-04-03). "The Unique Document of the Emir of Mecca from 1917: 'Help the Armenians How You Would Help Your Brothers'" (in en-US). https://allinnet.info/world/the-unique-document-of-the-emir-of-mecca/.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Gelbert, Carlos (2011). Ginza Rba. Sydney: Living Water Books. ISBN 9780958034630. https://livingwaterbooks.com.au/product/ginza-rba/.

- ↑ Gelbert, Carlos (2017). The Teachings of the Mandaean John the Baptist. Fairfield, NSW, Australia: Living Water Books. ISBN 9780958034678. OCLC 1000148487. https://livingwaterbooks.com.au/product/john-the-baptist/.

- ↑ "Baháʼí Reference Library – The Hidden Words of Bahá'u'lláh, p. 11". Reference.bahai.org. 31 December 2010. http://reference.bahai.org/en/t/b/HW/hw-31.html.

- ↑ "The Golden Rule Baháʼí Faith". Replay.waybackmachine.org. 11 April 2009. http://www.bahainyc.org/presentations/goldenrule/golden-rule10.html.

- ↑ Tablets of Bahá'u'lláh, p. 71

- ↑ "The Hidden Words of Bahá'u'lláh – Part II". Info.bahai.org. http://info.bahai.org/article-1-3-2-9.html.

- ↑ Epistle to the Son of the Wolf, p. 30

- ↑ Words of Wisdom See: The Golden Rule

- ↑ Bahá'u'lláh, Gleanings, LXVI:8

- ↑ Hidden Words of Bahá'u'lláh, p. 10

- ↑ "Mahabharata Book 13". Mahabharataonline.com. 13 November 2006. http://www.mahabharataonline.com/translation/mahabharata_13b078.php.

- ↑ tasmād dharma-pradhānéna bhavitavyam yatātmanā | tathā cha sarva-bhūtéṣhu vartitavyam yathātmani ||

तस्माद्धर्मप्रधानेन भवितव्यं यतात्मना। तथा च सर्वभूतेषु वर्तितव्यं यथात्मनि॥|title = Mahābhārata Shānti-Parva 167:9) - ↑ Singleton, Esther. "Gautama Buddha (B.C. 623-543)" by T.W. Rhys-Davids, The World's Great Events, B.C. 4004–A.D. 70 (1908). pp. 124–135.

- ↑ "The Buddha (BC 623–BC 543) – Religion and spirituality Article – Buddha, BC, 623". Booksie. 8 July 2012. http://www.booksie.com/religion_and_spirituality/article/myoma_myint_kywe/the-buddha-%28bc-623bc-543%29.

- ↑ Detachment and Compassion in Early Buddhism by Elizabeth J. Harris (enabling.org)

- ↑ Jacobi, Hermann (1884). Ācāranga Sūtra, Jain Sutras Part I, Sacred Books of the East. 22. Sutra 155–156. http://www.sacred-texts.com/jai/sbe22/index.htm. Retrieved 22 November 2007.

- ↑ Plaks, A. H. (2015). "Shining Ideal and Uncertain Reality: Commentaries on the 'Golden Rule' in Confucianism and Other Traditions". Journal of Chinese Humanities, 1(2), 231–240.

- ↑ Ivanhoe and Van Norden translation, 68–69

- ↑ Gensler, Harry J. (2013) (in en). Ethics and the Golden Rule. Routledge. pp. 100. ISBN 978-1-136-57793-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=40ZfEsGiqHwC&pg=PA100. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ↑ Bewaji, John Ayotunde Isola; Harrow, Kenneth W.; Omonzejie, Eunice E. (2017-05-11) (in en). The Humanities and the Dynamics of African Culture in the 21st Century. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-9355-8. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Humanities_and_the_Dynamics_of_Afric/vXHXDgAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Egbe+bere,+ugo+bere.++%09++++Let+the+eagle+perch,+let+the+hawk+perch.++%E2%80%94Igbo+proverb&pg=PA48&printsec=frontcover.

- ↑ "Towards a Global Ethic". Urban Dharma – Buddhism in America. (This link includes a list of 143 signatories and their respective religions.)

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 "Towards a Global Ethic"[Usurped!] (An Initial Declaration). ReligiousTolerance.org. Under the subtitle, "We Declare", see third paragraph. The first line reads, "We must treat others as we wish others to treat us."

- ↑ "Parliament of the World's Religions – Towards a Global Ethic". http://www.parliamentofreligions.org/_includes/FCKcontent/File/TowardsAGlobalEthic.pdf.

- ↑ Esptein, Greg M. (2010). Good Without God: What a Billion Nonreligious People Do Believe. New York: HarperCollins. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-06-167011-4. https://archive.org/details/goodwithoutgodwh00epst/page/115. Italics in original.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 "The Golden Rule". http://www.thinkhumanism.com/the-golden-rule.html.

- ↑ "Think Humanism". Think Humanism. http://www.thinkhumanism.com/.

- ↑ "A decalogue for the modern world". Ebonmusings.org. 1 January 1970. http://www.ebonmusings.org/atheism/new10c.html.

- ↑ Sartre, Jean-Paul (2007). Existentialism Is a Humanism. Yale University Press. pp. 291–292. ISBN 978-0-300-11546-8.

- ↑ Mill, John Stuart (1979). "Chapter 2 - What Utilitarianism Is". in Sher, George. Utilitarianism. Indianapolis and Cambridge: Hackett. p. 16. ISBN 0-915144-41-7.

- ↑ Defined another way, it "refers to the balance in an interactive system such that each party has both rights and duties, and the subordinate norm of complementarity states that one's rights are the other's obligation."Bornstein, Marc H. (2002). Handbook of Parenting. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-8058-3782-7. See also: Paden, William E. (2003). Interpreting the Sacred: Ways of Viewing Religion. Beacon Press. pp. 131–132. ISBN 978-0-8070-7705-4.

- ↑ Damrosch, Leo (2008). Jean Jacques Russeau: Restless Genius. Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 978-0-618-44696-4. https://archive.org/details/jeanjacquesrouss00leod.

- ↑ "How the Platinum Rule Trumps the Golden Rule Every Time" (in en). Inc.com. https://www.inc.com/peter-economy/how-the-platinum-rule-trumps-the-golden-rule-every-time.html.

- ↑ Max Chochinov, OC, PhD, MD, FRCPC, Harvey (18 May 2022). "The Platinum Rule: A New Standard for Person-Centered Care". Journal of Palliative Medicine 25 (6): 854–856. doi:10.1089/jpm.2022.0075. PMID 35230173.

- ↑ McClanahan, C. J.. "Council Post: The Platinum Rule: Why It's Time To Forget How You Want To Be Treated" (in en). https://www.forbes.com/councils/forbescoachescouncil/2020/03/23/the-platinum-rule-why-its-time-to-forget-how-you-want-to-be-treated/.

- ↑ ""The Platinum Rule": A new leadership mindset for improved work and personal relationships". https://www.livingasaleader.com/Resources/Leadership-Blog/The-Platinum-Rule-A-new-leadership-mindset-for-improved-work-and-personal-relationships.htm.

- ↑ Pfaff, Donald W., "The Neuroscience of Fair Play: Why We (Usually) Follow the Golden Rule", Dana Press, The Dana Foundation, New York, 2007. ISBN 978-1-932594-27-0

- ↑ Wattles, Jeffrey (1996). The Golden Rule. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Vogel, Gretchen. "The Evolution of the Golden Rule". Science 303 (Feb 2004).

- ↑ Swift, Richard (July 2015). "Pathways & possibilities". New Internationalist 484 (July/August 2015).

- ↑ Smith, Kerri (June 2005). "Is it a chimp-help-chimp world?". Nature 484 (Online publication). http://www.nature.com/news/2007/070625/full/070625-4.html. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ↑ 110.0 110.1 Kant, Immanuel Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, footnote 12. Cambridge University Press (28 April 1998). ISBN 978-0-521-62695-8

- ↑ "Only a Game: The Golden Rule". Onlyagame.typepad.com. 24 May 2007. http://onlyagame.typepad.com/only_a_game/2007/05/the_golden_rule.html.

- ↑ Pauling, Linus (1960). Fallout: Today's Seven-Year Plague. New York: Mainstream Publishers.

- ↑ Shaw, George Bernard (1903). Man and Superman. Archibald Constable & Co.. p. 227. https://archive.org/stream/mansupermancomed00shawrich#page/226/mode/2up. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- ↑ 114.0 114.1 King, Iain (16 December 2008). How to Make Good Decisions and Be Right All the Time. London ; New York: A&C Black. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-84706-347-2.

- ↑ Stace, Walter T. (1975). The Concept of Morals. Gloucester, Mass: Peter Smith Publisher. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-8446-2990-2.

- ↑ Alston, William P.; Brandt, Richard B., eds (1978). The Problems of Philosophy. Boston, London, Sydney, Toronto: Allyn and Bacon. p. 139. ISBN 978-0205061105.

- ↑ Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm. (1989). "Reflections on the Common Concept of Justice". in Leroy E. Loemker.. Philosophical Papers and Letters.. Boston: Kluwer. p. 568.

- ↑ M. G. Singer, The Ideal of a Rational Morality, p. 270

- ↑ Wattles, p. 6

- ↑ Jouni Reinikainen, "The Golden Rule and the Requirement of Universalizability." Journal of Value Inquiry. 39(2): 155–168, 2005.

- ↑ Karl Popper, The Open Society and Its Enemies, Vol. 2 (1966 [1945]), p. 386. Dubbed "the platinum rule" in business books such as Charles J. Jacobus, Thomas E. Gillett, Georgia Real Estate: An Introduction to the Profession, Cengage Learning, 2007, p. 409 and Jeremy Comfort, Peter Franklin, The Mindful International Manager: How to Work Effectively Across Cultures, Kogan Page, p. 65.

- ↑ "Mary Wakefield: What 'The Water Babies' can teach us about personal". The Independent. 22 October 2011. https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/commentators/mary-wakefield-what-the-water-babies-can-teach-us-about-personal-morality-1850416.html.

External links

- The Golden Rule Movie A teaching resource.

- Golden Rule Day An annual global event every April 5.

- Golden Rule Project - learning tools, etc. (based in Salt Lake City, Utah, US)

- Monmouth Center for World Religions and Ethical Thought. The Golden Rule

- Puka, Bill. "The Golden Rule". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://www.iep.utm.edu/goldrule.

- Scarboro Mission. The Golden Rule Educational, participatory, and interactive resources including videos, exercises, multi-disciplinary commentaries, The Golden Rule Poster, and interfaith dialogues on the Golden Rule.

- St Columbans Mission Society – Interfaith Relations. The Golden Rule The Golden Rule Poster, etc.

|

KSF

KSF