Humanist photography

Topic: Philosophy

From HandWiki - Reading time: 12 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 12 min

Humanist Photography, also known as the School of Humanist Photography,[1] manifests the Enlightenment philosophical system in social documentary practice based on a perception of social change. It emerged in the mid-twentieth-century and is associated most strongly with Europe, particularly France ,[2] where the upheavals of the two world wars originated, though it was a worldwide movement. It can be distinguished from photojournalism, with which it forms a sub-class of reportage, as it is concerned more broadly with everyday human experience, to witness mannerisms and customs, than with newsworthy events, though practitioners are conscious of conveying particular conditions and social trends, often, but not exclusively, concentrating on the underclasses or those disadvantaged by conflict, economic hardship or prejudice. Humanist photography "affirms the idea of a universal underlying human nature".[3] Jean Claude Gautrand describes humanist photography as:[4]

a lyrical trend, warm, fervent, and responsive to the sufferings of humanity [which] began to assert itself during the 1950s in Europe, particularly in France ... photographers dreamed of a world of mutual succour and compassion, encapsulated ideally in a solicitous vision.

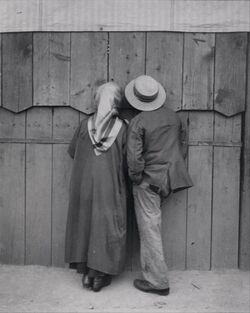

Photographing on the street or in the bistro primarily in black‐and‐white in available light with the popular small cameras of the day, these image-makers discovered what the writer Pierre Mac Orlan (1882-1970) called the 'fantastique social de la rue' (social fantasticality of the street)[5] and their style of image making rendered romantic and poetic the way of life of ordinary European people, particularly in Paris.

Philosophical foundation

The preoccupation with everyday life emerged after World War I. As a reaction to the atrocities of the trenches, Paris became a haven for intellectual, cultural and artistic life,[6] attracting artists from the whole of Europe and the United States.[7] With the release of the first Leica and Contax range-finder cameras, photographers took to the street and documented life by day and night.[8] Such photographers as André Kertész, Brassaï, Henri Cartier-Bresson emerged during the period between the two world wars thanks to the Illustrated Press (Vu and Regards). Having been brought to notice by the Surrealists and Berenice Abbott, the life work of Eugène Atget in the empty streets of Paris also became a reference.

At the end of World War II, in 1946, French intellectuals Jean-Paul Sartre and André Malraux embraced humanism;[9] Sartre argued that existentialism was a humanism entailing freedom of choice and a responsibility for defining oneself,[10] while at the Sorbonne in an address sponsored by UNESCO, Malraux depicted human culture as 'humanisme tragique', a battle against biological decay and historical disaster.[11]

Emerging from brutal global conflict, survivors desired material and cultural reconstruction and the appeal of humanism was a return to the values of dignity, equality and tolerance[12] symbolised in an international proclamation and adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the General Assembly of the United Nations in Paris on 10 December 1948.[13] That the photographic image could become a universal language in accord with these principles was a notion circulated at a UNESCO conference in 1958 [14]

Emergence

As France in particular,[15] but also Belgium and the Netherlands, emerged from the dark period of the Occupation (1940–4), the liberation of Paris in August 1944 released photographers to respond to reconstruction[16] and the Fourth Republic's (1947–59) drive to redefine a French identity after war, defeat, occupation, and collaboration, and to modernise the country.[2] For photographers the experience had been one in which the Nazi authorities censored all visual expression and the Vichy carefully controlled those who remained;[17] and who eked out a living with portraiture and commercial, officially endorsed editorial photography, though individuals joined the Resistance from 1941, including Robert Capa, Cartier-Bresson,[18] and Jean Dieuzaide,[1] with several forging passes and documents (amongst whom were Robert Doisneau, Hans Bellmer, and Adolfo Kaminsky).

Paris was a crossroad of modernist culture and so cosmopolitan influences abound in humanist photography, recruiting emigrés who impressed their stamp on French photography, the earliest being Hungarian André Kertész who arrived on the scene in the mid-1920s; followed by his compatriots Ergy Landau, Brassai (Gyula Halasz), and Robert Capa (Endre Friedmann), and by the Pole "Chim" Seymour (Dawid Szymin), among others, in the 1930s.[2] The late 1940s and 50s saw a further influx of foreign photographers sympathetic to this movement, including Ed van der Elsken from the Netherlands who recorded the interactions at the bistrot Chez Moineau, the dirt-cheap refuge of bohemian youths and of Guy Debord, Michele Bernstein, Gil J. Wolman, Ivan Chtcheglov and the other members of the Letterist International[19] and the emerging Situationists whose theory of the dérive[20] accords with the working method of the humanist street photographer.

Picture magazines, reportage and the photoessay

Humanist photography emerged and spread after the rise of the mass circulation picture magazines in the 1920s and as photographers formed fraternities such as Le Groupe des XV (which exhibited annually 1946-1957),[21] or joined agencies which promoted their work and fed the demand of the newspaper and magazine audiences, publishers and editors before the advent of television broadcasting which rapidly displaced these audiences at the close of the 1960s. These publications include the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung, Vu, Point de Vue, Regards, Paris Match, Picture Post, Life, Look, Le Monde illustré, Plaisir de France and Réalités which competed to give ever larger space to photo-stories; extended articles and editorials that were profusely illustrated, or that consisted solely of photographs with captions, often by a single photographer, who would be credited alongside the journalist, or who provided written copy as well as images.

Photobooks and literary connections

Iconic books appeared including Doisneau's Banlieue de Paris (1949), Izis's Paris des rêves (1950), Willy Ronis' Belleville‐Ménilmontant (1954), and Cartier‐Bresson's Images à la sauvette (1952); better known by its English title, which defines the photographic orientation of all these photographers, The Decisive Moment).

Exhibitions

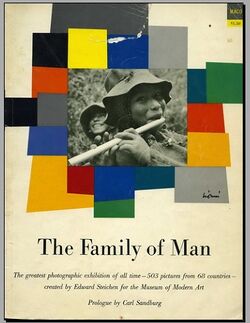

National and international exposure of humanist photography was accelerated through exhibitions and of particular importance in this regard is The Family of Man, a vast travelling exhibition curated by Edward Steichen for MoMA, which presented a unifying humanist manifesto in the form of images selected from amongst, literally, a million. Thirty-one French photographs appeared in The Family of Man, a contribution representing almost one-third of the European photography in the show.[22]

Steichen said that based on his experience of meeting photographers in Europe as he sought images of ‘everydayness' which he defined as 'the beauty of the things that fill our lives',[23] for the exhibition, that the French were the only photographers who had thoroughly photographed scenes of daily life. These were practitioners he admired for their conveying 'tender simplicity, a sly humor, a warm enthusiasm ... and convincing aliveness'.[24] In turn, this exposure in The Family of Man inspired a new generation of humanist photographers.[25]

- 1946–1957 Le Groupe des XV (Marcel Amson, Jean Marie Auradon, Marcel Bovis, Louis Caillaud, Yvonne Chevallier, Jean Dieuzaide, Robert Doisneau, André Garban, Édith Gérin, René-Jacques (René Giton), Pierre Jahan, Henri Lacheroy, Therese Le Prat, Lucien Lorelle, Daniel Masclet, Philippe Pottier, Willy Ronis, Jean Séeberger, René Servant, Emmanuel Sougez, François Tuefferd) exhibited annually in Paris.

- 1951: During his visit to Europe collecting photographs for The Family of Man, Edward Steichen mounted the exhibition Five French Photographers: Brassai; Cartier-Bresson, Doisneau, Ronis, Izis at MoMA December 1951-24 February 1952.[26]

- 1953: Steichen presented a second exhibition Post-war European Photography at MoMA, 27 May-2 August 1953.[27]

- 1955: Steichen drew on large numbers of European humanist and American humanistic photographs for his exhibition The Family of Man], proclaimed as a compassionate portrayal of a global family, which toured the world.

- 1982: Paris 1950: photographié par le Groupe des XV, exhibition at the Bibliothèque historique de la Ville de Paris, 5 November 1982 – 29 janvier 1983.

- 1996: In April 1996, the inaugural exhibition of the Maison de la Photographie Robert Doisneau, entitled This Is How Men Live: Humanism and Photography presented 80 photographers from 17 different countries and covered a period from 1905 to today. The Maison de la Photographie Robert Doisneau has been dedicated to humanist photography inspired by revisiting the concept, including all countries and eras.

- 2006: The exhibition The humanistic picture (1945-1968) featuring Izis, Boubat, Brassaï, Doisneau, Ronis, et al. took place in the Mois de Photo festival from 31 October 2006 to 28 January 2007 at the BNF, Site Richelieu.

Humanist photography outside France

England

The British, exposed to much the same threats and conflict as the rest of Europe during the first half of the century, in their popular magazine Picture Post (1938–1957) did much to promote the humanist imagery[28] of Bert Hardy,[29][30] Kurt Hutton, Felix H. Man (aka Hans Baumann), Francis Reiss, Thurston Hopkins, John Chillingworth, Grace Robertson, and Leonard McCombe, who eventually joined Life Magazine's staff. Its founder Stefan Lorant explained his motivation;

“Father was a humanist. When I lost him in the war, it changed me. He was in his forties, and I changed. I championed the cause of the common man, for people who were not as well off as myself”[31]

United States

The movement is in marked contrast to the contemporaneous ‘art’ photography of the USA, which was a country less directly exposed to the trauma that inspired the humanist philosophy.[32] Nevertheless, there too ran a current of humanism in photography, first begun in the early 20th century by Jacob Riis,[33] then Lewis Hine, followed by the FSA and the New York Photo League [see the Harlem Project led by Aaron Siskind] photographers exhibited at Limelight gallery.[34]

Books were published such as those by Dorothea Lange[8] and Paul Taylor (An American Exodus, 1939), Walker Evans and James Agee (Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, 1941), Margaret Bourke-White and Erskine Caldwell (You Have Seen Their Faces, 1937), Arthur Rothstein and William Saroyan (Look At Us,..., 1967). The seminal work by Robert Frank, The Americans published in France in 1958 (Robert Delpire) and the USA the following year (Grove Press), the result of his two Guggenheim grants, can also be considered an extension of the humanist photography current in the USA which had a demonstrable impact on American photography.[8]

In spite of the Red Scare and McCarthyism in the 1950s (which banned the Photo League) a humanist ethos and vision was promoted by The Family of Man exhibition world tour, and is strongly apparent in W. Eugene Smith's 1950s development of the photo essay, street photography by Helen Levitt, Vivian Maier et al., and later the work by Bruce Davidson (incl. his East 100th Street), Eugene Richards, and Mary-Ellen Mark from the 50s into the 90s.[35] The W. Eugene Smith Award continues to award humanitarian and humanist photography.[36]

Characteristics

Typically humanist photographers harness the photograph's combination of description and emotional affect to both inform and move the viewer, who may identify with the subject; their images are appreciated as continuing the pre-war tradition of photo reportage as social or documentary records of human experience. It is praised for expressing humanist values such as empathy, solidarity, sometimes humor, and mutual respect of cameraperson and subject in recognition of the photographer, usually an editorial freelancer, as auteur on a par with other artists.[37]

Developments in technology supported these characteristics. The Ermanox with its fast f/1.8 and f/2 lenses (6 cm x 4.5 cm format, 1924) and the 35mm Leica, 1925) camera, miniaturized and portable, had become available by the end of the 1920s, followed by the medium-format Rolleiflex (1929), and the 35mm Contax (1936). They revolutionized the practice of documentary photography and reportage by enabling the photographer to shoot quickly and unobtrusively in all conditions, to seize the "decisive moment" which Cartier-Bresson defined as "the whole essence, in the confines of one single photograph, of some situation that was in the process of unrolling itself before my eyes"[38] and thus support Cornell Capa's notion of "concerned photography", described as "work committed to contributing to or understanding humanity's well-being".[39]

Decline

The humanist current continued into the late 1960s and early 70s, also in the United States[32] when America came to dominate the medium,[40] with photography in academic artistic and art history programs becoming institutionalised in such programs as the Visual Studies Workshop,[41] after which attention turned to photography as a fine art and documentary image-making was interrogated and transformed in Postmodernism.[42][43]

Humanist photographers

The list below is not exhaustive, but presents photographers that can be partially or totally attached to this movement:

- Ilse Bing

- Werner Bischof

- Édouard Boubat

- Marcel Bovis

- Brassaï

- Henri Cartier-Bresson

- Jean-Philippe Charbonnier

- Peter Cornelius

- Dominique Darbois (Dominique Stern)

- Robert Doisneau[44]

- Henriette Grindat

- Dave Heath

- Frank Horvat

- Izis (Israëlis Bidermanas)

- Pierre Jahan

- Ergy Landau

- Dorothea Lange

- Lucien Lorelle

- Vivian Maier

- René Maltête

- Ervin Marton

- Olivier Meyer

- Inge Morath

- Janine Niépce

- Gilles Peress

- Marc Riboud

- Manuel Rivera-Ortiz

- Willy Ronis[45]

- Émile Savitry

- Roger Schall

- Bill Schwab

- W. Eugene Smith

- Louis Stettner

- Yvette Troispoux

- François Tuefferd

- Sabine Weiss

- Véro (Werner Rosenberg)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Chalifour, Bruno, 'Jean Dieuzaide, 1935-2003' in Afterimage Vol. 31, No. 4, January–February 2004

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Hamilton, P. (2001). " A poetry of the streets?" Documenting Frenchness in an Era of Reconstruction: Humanist Photography 1935-1960. In The Documentary Impulse in French Literature

- ↑ Lutz, C.A. and Collins, J.L. (1993) Reading National Geographic. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p.277

- ↑ Jean-Claude Gautrand, 'Looking at Others: Humanism and neo-realism', in The New History of Photography, ed. Michel Frizot, K61n: K6nemann, 1998, 613.

- ↑ in the preface by Pierre Mac Orlan to Ronis, Willy (1954), Belleville-Ménilmontant, Arthaud, http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/16070565, retrieved 29 February 2016

- ↑ Bouvet, Vincent; Durozoi, Gérard; Sharman, Ruth Verity (November 2010), Paris between the wars, 1919-1939 : art, life & culture, Vendome Press (published 2010), ISBN 978-0-86565-252-1

- ↑ Lévy, Sophie; Terra Museum of American Art; Tacoma Art Museum; Musée américain Giverny (2003), Paris, capitale de l'Amérique : l'avant-garde américaine à Paris, 1918-1939, A. Biro ; Giverny : Musée d'art américain Giverny ; [Chicago] : Terra Foundation for the Arts, ISBN 978-2-87660-386-8

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Wells, Liz, 1948-, (editor.); Henning, Michelle, (contributor.) (2015), Photography : a critical introduction (Fifth ed.), Routledge, p. 119, ISBN 978-1-315-72737-0

- ↑ Smith, D. Funny Face: Humanism in Post-War French Photography and Philosophy. French Cultural Studies February 2005 vol. 16 no. 1 41-53

- ↑ Sartre, J.-P. (1996) L’Existentialisme est un humanisme. Paris: Gallimard.

- ↑ Malraux, A. (1996) ‘L’Homme et la culture’, in J. Mossuz-Lavau (ed.), La Politique, la culture: discours, articles, entretiens (1925–1975), pp. 151–61. Paris: Gallimard.

- ↑ Poirier, Agnès Catherine; ProQuest (Firm) (8 March 2018), Left Bank : art, passion, and the rebirth of Paris, 1940-50 (First ed.), Bloomsbury Publishing ; New York, New York : Henry Holt and Company (published 2018), ISBN 978-1-4088-5746-5

- ↑ Kelly, M. (1989) ‘Humanism and National Unity: The Ideological Reconstruction of France’, in N. Hewitt (ed.), The Culture of Reconstruction: European Literature, Thought and Film, 1945–50, pp. 103–19. London: Macmillan.

- ↑ An international centre of photography and moving pictures was created, then, during the UNESCO General Conference in New Delhi, an international of film and television, non-profit organisation dedicated primarily to education, culture and development of the international associations concerned was proposed by the Italian delegation to UNESCO, with Professor Mario Verdone, and on 23 October 1958 the International Council for Cinema, Television and Audiovisual Communication charter was signed.

- ↑ Thézy (Marie de), La Photographie humaniste, 1930-1960. Histoire d’un mouvement en France, Paris, Contrejour, 1992.

- ↑ Reconstructions et modernisation. La France après les ruines (1918-1945), [catalogue de l’exposition aux Archives nationales, Paris, hôtel de Rohan, janvier-mai 1991], Paris, Archives nationales, 1991

- ↑ Hamilton, P. 'Representing the social : France and Frenchness in post-war humanist photography'. In Hall, Stuart; Open University (8 April 1997), Representation : cultural representations and signifying practices, Sage, in association with The Open University (published 1997), p. 127, ISBN 978-0-7619-5432-3, https://archive.org/details/representationcu0000unse/page/127

- ↑ Henri Cartier-Bresson was one who in 1943 joined Communist resistance fighters, the future National Movement for Prisoners of War and Deportees Cartier-Bresson, H., & Chéroux, C. (1976). Henri Cartier-Bresson (Vol. 1). F. Mapfre (Ed.). Aperture.

- ↑ Andreotti, Libero. "Play-Tactics of the "Internationale Situationniste". October, Vol. 9 (Winter, 2000), pp. 36-58: The MIT Press

- ↑ Guy Debord (1955) Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography. Les Lèvres Nues #6 (Paris, September 1955). Translated by Ken Knabb.

- ↑ Paris 1950 photographié par le Groupe des XV; Marie de Thézy; Marcel Bovis; Catherine Floc'hlay; Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris; Paris (France). Direction des affaires culturelles. 1982. (OCLC 50603400)

- ↑ Kristen Gresh (2005) The European roots of The Family of Man, History of Photography, 29:4, 331-343, DOI: 10.1080/03087298.2005.10442815

- ↑ Minutes, meeting at MoMA, 29 October 1953, typescript in Edward Steichen Archive, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

- ↑ Steichen quoted by Jacob Deschin, 'The Work of French Photographers', New York Times (23 December 1951), X14.

- ↑ The exhibition, for example, inspired Sune Jonsson (Swedish, b. 1930) to become a photographer and influenced the nature of his work. Anna Tellgren, Ten Photographers: Self- perception and Pictorial Perception: Swedish Photography in the 1950s in an International Perspective, Stockholm: InformationsfOrlaget 1997, 275.

- ↑ "For a contemporary review see Jacob Deschin, 'The Work of French Photographers', New York Times (23 December 1951), X14. The u.s. Camera Annual 1953 includes a selection of photographs from the exhibition under the revised title, Four French Photographers: Brassai, Doisneau, Ronis, Izis" (because he could not be contacted by time of publication, Cartier-Bresson was omitted) Kristen Gresh (2005) The European roots of The Family of Man, History of Photography, 29:4, 331-343, DOI: 10.1080/03087298.2005.10442815

- ↑ Jacob Deschin, 'European Pictures: Modern Museum Presents Collection by Steichen', New York Times (31 May 1953), X13; US. Camera Annual 1954, ed. Tom Maloney, New York: U.S. Camera Publishing Co. 1953.

- ↑ Jordan, Glenn; Hardy, Bert; Butetown History & Arts Centre (May 2003), 'Down the Bay' : Picture Post, humanist photography and images of 1950s Cardiff, Butetown History & Arts Centre (published 2001), ISBN 978-1-898317-08-1, https://archive.org/details/downbaypicturepo0000jord

- ↑ Swenarton, Mark; Troiani, Igea; Webster, Helena (15 April 2013), The Politics of Making, Taylor and Francis (published 2013), p. 234, ISBN 978-1-134-70938-0

- ↑ Campkin, Ben (13 August 2013), Remaking London : Decline and regeneration in urban culture, I.B. Tauris (published 2013), ISBN 978-0-85772-272-0

- ↑ Hallett, Michael (2006), Stefan Lorant : godfather of photojournalism, The Scarecrow Press, ISBN 978-0-8108-5682-0

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Carter, Christopher (30 April 2015), Rhetorical exposures : confrontation and contradiction in US social documentary photography, The University of Alabama Press (published 2015), ISBN 978-0-8173-1862-8

- ↑ Abbott, Brett; J. Paul Getty Museum (2010), Engaged observers : documentary photography since the sixties, J. Paul Getty Museum, p. 4, ISBN 978-1-60606-022-3

- ↑ Kozloff, Max; Levitov, Karen; Goldfeld, Johanna; Musée de l'Elysée (Lausanne, Switzerland); Madison Art Center; Jewish Museum (New York, N.Y.) (2002). New York : capital of photography. Jewish Museum ; New Haven : Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09332-2. https://archive.org/details/newyorkcapitalof0000kozl.

- ↑ Erik Mortenson (2014) The Ghost of Humanism: Rethinking the Subjective Turn in Postwar American Photography, History of Photography, 38:4, 418-434, DOI: 10.1080/03087298.2014.899747

- ↑ Silverman, Rena (14 October 2015). "W. Eugene Smith Grants Honor Humanistic Photography". The New York Times. http://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/10/14/w-eugene-smith-grants-honor-humanistic-photography/.

- ↑ Chevrier, J.-F. (1987a) ‘Photographie 1947: le poids de la tradition', in J.-L. Daval (ed.), L'Art en Europe: les années décisives 1945–1953, pp. 177–89. Geneva: Skira/Musée d'art moderne de Saint-Étienne

- ↑ Cartier-Bresson, Henri; Matisse, Henri, 1869-1954; Tériade, E; Lang, Marguerite (1952), The decisive moment : photography, Simon and Schuster, http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/9145040, retrieved 29 February 2016

- ↑ Cornell Capa, ed., The Concerned Photographer (vols. 1-2), New York: Grossman Publishers 1968, 1972.

- ↑ Nye, David E., 1946-; Gidley, M. (Mick) (1994). American photographs in Europe. VU University Press. p. 208. ISBN 978-90-5383-304-9.

- ↑ "Centrist Liberalism Triumphant: Postwar Humanist Reframing of Documentary - Still searching - Fotomuseum Winterthur" (in en). Fotomuseum Winterthur. http://www.fotomuseum.ch/en/explore/still-searching/series/27029_centrist_liberalism_triumphant_postwar_humanist_reframing_of_documentary.

- ↑ Fogle, Douglas; Walker Art Center; UCLA Hammer Museum of Art and Cultural Center (2003). The last picture show : artists using photography, 1960-1982 (1st ed.). Walker Art Center. ISBN 978-0-935640-76-2.

- ↑ {{Citation | author1=Davis, Douglas | author2=Davis, Douglas, 1933- | author3=Holme, Bryan, 1913- | title=Photography as fine art | publication-date=1983 | publisher=Thames and Hudson | isbn=978-0-500-27300-5 }

- ↑ Peter Hamilton (1995), Robert Doisneau a photographer's life (1st ed.), New York Abbeville Press, ISBN 978-0-7892-0020-4

- ↑ Hamilton, Peter; Ronis, Willy, 1910-; Museum of Modern Art (Oxford, England) (1995), Willy Ronis : photographs 1926-1995, Museum of Modern Art, https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/21410399, retrieved 21 October 2019

|

KSF

KSF