Jain epistemology

Topic: Philosophy

From HandWiki - Reading time: 4 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 4 min

Jainism made its own unique contribution to this mainstream development of philosophy by occupying itself with the basic epistemological issues. According to Jains, knowledge is the essence of the soul.[1] This knowledge is masked by the karmic particles. As the soul obtains knowledge through various means, it does not generate anything new. It only shreds off the knowledge-obscuring karmic particles. According to Jainism, consciousness is a primary attribute of Jīva (soul) and this consciousness manifests itself as darsana (perception) and jnana (knowledge).

Overview

According to Jain text, Tattvartha sutra, knowledge (Jnana) is of five kinds:[2][3]-

- Sensory knowledge (Mati Jnana)

- Scriptural knowledge (Shruta Jnana)

- Clairvoyance (Avadhi Jnana)

- Telepathy (manahparyaya jnana)

- Omniscience (Kevala Jnana)

The first two kinds of knowledge are through indirect means and remaining three are through direct means.[4][2] Indirect means includes inference, analogy, word or scripture, presumption and probability.[2]

Sensory knowledge

The knowledge acquired through the empirical perception and mind is termed as Mati Jnana (Sensory knowledge).[2] According to Jain epistemology, sense perception is the knowledge which the Jīva (soul) acquires of the environment through the intermediary of material sense organs.[5] This includes recollection, recognition, induction based on observation and deduction based on reasoning.[2] This is divided into five processes:[6][7]

- Vyanjanavagraha (contact of an object)

- Arthavagraha (presentation of object or first observation)

- Iha (urge to apprehend the object or curiosity)

- Apaya (confirmation)

- Dharana (definite knowledge or impression)

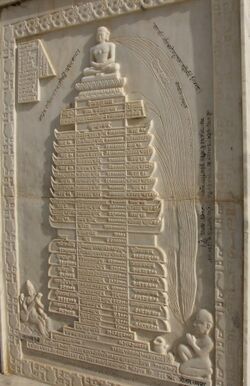

Scriptural knowledge

The knowledge acquired through understanding of verbal and written sentences etc., is termed as Śhrut Jnāna.[8]

Scripture is not knowledge because scripture does not comprehend anything. Therefore, knowledge is one thing and scripture another; this has been proclaimed by the Omniscient Lord.

— Samayasāra (10-83-390)[9]

As per Jains, the knowledge of Śhrut Jnāna, may be angaparivastam (things which are contained in the Angas, limbs or sacred Jain books) or angabahyam (things outside the Angas).[8][10] They are further subdivided into 12 kinds each.[8] This raises aspirations for quiescence of mind, right determination, disposition to realize the truth and character-formation.[8]

Clairvoyance

Clairvoyance is mentioned as avadhi jnana in Jain scriptures.[11] According to Jain text Sarvārthasiddhi, "this kind of knowledge has been called avadhi as it ascertains matter in downward range or knows objects within limits".[12] The beings of hell and heaven (devas) are said to possess clairvoyance by birth. Six kinds of clairvoyance is mentioned in the Jain scriptures.[13]

Telepathy

According to Jainism, the soul can directly know the thoughts of others. Such knowledge comes under the category of 'Manhaparyaya Jnana'.

Omniscience

By Shredding of the karmic particles, the soul acquires perfect knowledge. With such a knowledge, the knowledge and soul becomes one. Such a knowledge is Kevala Jnana.

Nature of the soul

Jains maintain that knowledge is the nature of the soul. According to Champat Rai Jain:

Knowledge is the nature of the soul. If it were not the nature of the soul, it would be either the nature of the not-soul, or of nothing whatsoever. But in the former case, the unconscious would become the conscious, and the soul would be unable to know itself or any one else, for it would then be devoid of consciousness; and, in the latter, there would be no knowledge, nor conscious beings in existence, which, happily, is not the case.[14]

Anekāntavāda

Anēkāntavāda refers to the principles of perspectivism and multiplicity of viewpoints, the notion that truth and reality are perceived differently from diverse points of view, and that no single point of view is the complete truth.[15]

Jains contrast all attempts to proclaim absolute truth with adhgajanyāyah, which can be illustrated through the parable of the "blind men and an elephant". This principle is more formally stated by observing that objects are infinite in their qualities and modes of existence, so they cannot be completely grasped in all aspects and manifestations by finite human perception. According to the Jains, only the Kevalis—omniscient beings—can comprehend objects in all aspects and manifestations; others are only capable of partial knowledge. Consequently, no single, specific, human view can claim to represent absolute truth.

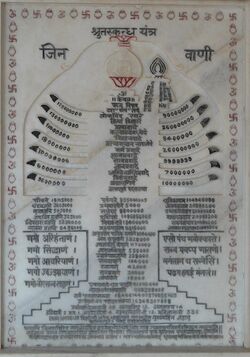

The doctrine of multiple viewpoints (Sanskrit: Nayavāda), holds that the ways of looking at things (Naya) are infinite in number.[16] This is manifested in scripture by use of conditional propositions, called Syādvāda (syād = 'perhaps, may be'). The seven used conditional principles are listed below.

- syād-asti: in some ways, it is;

- syād-nāsti: in some ways, it is not;

- syād-asti-nāsti: in some ways, it is, and it is not;

- syād-asti-avaktavyah: in some ways, it is, and it is indescribable;

- syād-nāsti-avaktavyah: in some ways, it is not, and it is indescribable;

- syād-asti-nāsti-avaktavyah: in some ways, it is, it is not, and it is indescribable;

- syād-avaktavyah: in some ways, it is indescribable.[17]

References

Citations

- ↑ Jaini 1927, p. 11.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Vyas 1995, p. 36.

- ↑ Jain 2011, p. 5.

- ↑ Jain 2011, p. 6.

- ↑ Jain, Vijay K. (2013). Ācārya Nemichandra's Dravyasaṃgraha. Vikalp Printers. p. 14. ISBN 9788190363952. https://books.google.com/books?id=g9CJ3jZpcqYC. "Non-copyright"

- ↑ Vyas 1995, pp. 36–37.

- ↑ Prasad 2006, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Vyas 1995, p. 37.

- ↑ Jain 2012, p. x.

- ↑ Jaini 1927, p. 12.

- ↑ Vyas 1995, p. 38.

- ↑ S. A. Jain 1992, p. 16.

- ↑ S. A. Jain 1992, p. 33.

- ↑ Jain, Champat Rai (1924). Nyaya. p. 11. https://books.google.com/books?id=9MYRnTo1r1oC. Alt URL

- ↑ Sethia 2004, pp. 123–136.

- ↑ "Syādvāda | Jainism | Britannica". https://www.britannica.com/topic/syadvada.

- ↑ Graham Priest, 'Jaina Log: A contemporary Perspective', History and Philosophy of Logic 29 (3): 263-278 (2008).

Sources

- Jain, Vijay K. (2012), Acharya Kundkund's Samayasara, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 978-81-903639-3-8, https://books.google.com/books?id=LwPT79iyRHMC

- Jain, Vijay K. (2011), Acharya Umasvami's Tattvarthsutra, ISBN 9788190363921, https://books.google.com/books?id=zLmx9bvtglkC, "Non-copyright"

- S. A. Jain (1992). Reality. Jwalamalini Trust. https://books.google.com/books?id=uRIaAAAAMAAJ. "Not in Copyright" Alt URL

- Jaini, Jagmandar-lāl (1927), Gommatsara Jiva-kanda, https://books.google.com/books?id=qN82XwAACAAJ Alt URL

- Sethia, Tara (2004), Ahiṃsā, Anekānta and Jainism, Motilal Banarsidass

- Prasad, Jyoti (2006), Religion & culture of the Jains, Delhi: Bharatiya Jnanpith

- Vyas, Dr. R. T., ed. (1995), Studies in Jaina Art and Iconography and Allied Subjects, The Director, Oriental Institute, on behalf of the Registrar, M.S. University of Baroda, Vadodara, ISBN 81-7017-316-7, https://books.google.com/books?id=fETebHcHKogC

KSF

KSF