Parametric determinism

Topic: Philosophy

From HandWiki - Reading time: 23 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 23 min

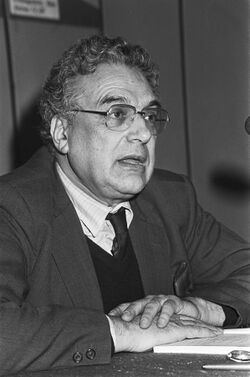

Parametric determinism is a Marxist interpretation of the course of history. It was formulated by Ernest Mandel and can be viewed as one variant of Karl Marx's historical materialism or as a philosophy of history.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism |

|---|

|

|

|

In an article critical of the analytical Marxism of Jon Elster, Mandel explains the idea as follows:

Dialectical determinism as opposed to mechanical, or formal-logical determinism, is also parametric determinism; it permits the adherent of historical materialism to understand the real place of human action in the way the historical process unfolds and the way the outcome of social crises is decided. Men and women indeed make their own history. The outcome of their actions is not mechanically predetermined. Most, if not all, historical crises have several possible outcomes, not innumerable fortuitous or arbitrary ones; that is why we use the expression 'parametric determinism' indicating several possibilities within a given set of parameters.[2]

Formal rationality and dialectical reason

In formal-logical determinism, human action is considered either rational, and hence logically explicable, or else arbitrary and random (in which case human actions can be comprehended at best only as patterns of statistical distributions, i.e. as degrees of variability relative to some constants). But in dialectical determinism, human action may be non-arbitrary and determinate, hence reasonable, even although it is not explicable exclusively in terms of deductive inference. The action selected by people from a limited range of options may not be the "most logical" or "most optimal" one, but it can be shown to be non-arbitrary and reasonable under the circumstances, if the total context is considered.[3]

What this means is that in human situations typically several "logics" are operating at the same time which together determine the outcomes of those situations:

- the logic of the actors themselves in their consciousness and actions;

- the logic of the given parameters constraining their behaviour; and

- the logic of the interactive (reflexive) relationship between actors and their situation.

If one considered only one of these aspects, one might judge people's actions "irrational", but if all three aspects are taken into account, what people do may appear "very reasonable". Dialectical theory aims to demonstrate this, by linking different "logical levels" together as a total picture, in a non-arbitrary way. "Different logical levels" means that particular determinants regarded as irrelevant at one level of analysis are excluded, but are relevant and included at another level of analysis with a somewhat different (or enlarged) set of assumptions depending on the kind of problem being investigated.[4]

For example, faced with a situation, the language which people use to talk about it, reveals that they can jump very quickly from one context to another related context, knowing very well that at least some of the inferences that can be drawn in the one context are not operative in the other context. That's because they know that the assumptions in one context differ to some degree from the other. Nevertheless, the two contexts can coexist, and can be contained in the same situation, which we can demonstrate by identifying the mediating links. This is difficult to formalize precisely, yet people do it all the time, and think it perfectly "reasonable". For another example, people will say "you can only understand this if you are in the situation yourself" or "on the ground." What they mean is that the meaning of the totality of interacting factors involved can only be understood by experiencing them. Standing outside the situation, things seem irrational, but being there, they appear very reasonable.

Dialectical theory does not mean that, in analyzing the complexity of human action, inconvenient facts are simply and arbitrarily set aside. It means, rather, that those facets of the subject matter which are not logically required at a given stage of the analysis are set aside. Yet, and this is the point, as the analysis progresses, the previously disregarded aspects are integrated step by step into the analysis, in a consistent way. The proof of the validity of the procedure is that, at the end, the theory has made the subject matter fully self-explanatory, since all salient aspects have been given their appropriate place in the theory, so that all of it becomes comprehensible, without resort to shallow tautologies.[5] This result can obviously be achieved only after the research has already been done, and the findings can be arranged in a convincing way. A synthesis cannot be achieved without a preceding analysis. So dialectical analysis is not a "philosopher's stone" that provides a quick short-cut to the "fount of wisdom", but a mode of presenting findings of the analysis after knowledge has been obtained through inquiry and research, and dialectical relationships have been verified. Because only then does it become clear where the story should begin and end, so that all facets are truly explained. According to Ernest Mandel, "Marx's method is much richer than the procedures of ' successive concretization' or 'approximation' typical of academic science."[6]

In mainstream social theory, the problem of "several logics" in human action is dealt with by game theory, a kind of modelling which specifies the choices and options which actors have within a defined setting, and what the effects are of their decisions. The main limitation of that approach is, that the model is only as good as the assumptions on which it is based, while the choice of assumptions is often eclectic or fairly arbitrary.[7] Dialectical theory attempts to overcome this problem, by paying attention to the sources of assumptions, and by integrating the assumptions in a consistent way.

Making history

One common problem in historical analysis is to understand to what extent the results of human actions can be attributed to free choices and decisions people made (or free will), and to what extent they are a product of social or natural forces beyond their control.[8]

To solve this problem theoretically, Mandel suggests that in almost any human situation, some factors ("parameters") are beyond the control of individuals, while some other conditions are under their control (arguably, one group of people could "impose parameters" on another, analogous to parents imposing constraints on children). Some things can under the circumstances be changed by human action, according to choice, but others cannot or will not be, and can thus be regarded as constants. A variable can vary, yet it cannot vary in any direction whatever but only within the given parameters. In a general sense, a "parameter" is a given condition imposed on a situation, or a controlled variable, but more specifically it refers to a condition which, in some way, limits the amount and type of variability there can be.

Those given, objective parameters which are beyond people's control (and thus cannot normally be changed by them) limit the realm of possibilities in the future; they rule out some conceivable future developments or alternatively make them more likely to happen. In that sense human action is "determined" and "determinate". If that wasn't so, then it would be impossible to predict anything much about human behaviour.

Some of these parameters refer to limits imposed by the physical world, others to limits imposed by the social set-up or social structure that individuals and groups operate within. The dominant ideology or religion could also be a given parameter. If for example most people follow a certain faith, this shapes their whole cultural life, and is something to be reckoned with that isn't easily changed.

At the same time, however, the given parameters cannot usually determine in total what an individual or group will do, because they have at least some (and sometimes a great deal) of personal or behavioural autonomy. They can think about their situation, and make some free choices and decisions about what they will do, within the framework of what is objectively possible for them (the choices need not be rational or fully conscious ones, they could just be non-arbitrary choices influenced by emotions and desires). Sentient (self-aware) organisms, of which human beings are the most evolved sort, are able to vary their own response to given situations according to internally evaluated and decided options. In this sense, Karl Marx had written:

People make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.[9]

"The past" (what really happened before, as distinct from its results in the present) is not something which can be changed at all in the present, only reinterpreted, and therefore the past is a given constant which delimits what can possibly happen in the present and in the future. If the future seems relatively "open-ended" that is just because in the time-interval between now and the future, new options and actions could significantly alter what exactly the future will be. Yet the variability of possible outcomes in the future is not infinite, but delimited by what happened before.

Ten implications

Ten implications of this view are as follows:

- At any point in time, the outcomes of an historical process are partly predetermined, and partly uncertain because they depend on what human choices and decisions will be made in the present. Those choices are not made in a vacuum, but in an environment which makes those choices possible, makes them meaningful and gives them effect. Otherwise they would not be real choices, only imaginary choices.

- While the past and the present rule out some courses of action, a human choice is always possible between a finite number of realistic options, which often enables the experienced analyst to specify the "most likely scenarios" of what could happen in the future. Some things cannot happen, and some things are more likely to happen than others.

- Once an important choice has been made and acted upon, this will have an effect on the realm of possibilities; in particular, it will shift to a greater or lesser extent the parameters delimiting what can happen in the future. Thus, once "a train of events has been set in motion", it will foreclose other possibilities, and also it might open up some new ones. If masses of people make important new choices, whether in response to circumstances or in response to a new idea, a qualitative change occurs; in that case, most people begin to behave differently.

- The process of history is both determined, in that the given parameters delimit the possible outcomes, but also open-ended, insofar as human action (or inaction) can change the historical outcomes within certain limits. Human history-making is therefore a reciprocal interaction between what people do, and the given circumstances.

- To some extent at least, it is possible to predict with useful accuracy what will happen in the future, if one has sufficient experience, knowledge, and insight into the relevant causal factors at work as well as how they are related. This may be a work of science or sustained practical experience. In turn, future perspectives can importantly influence human action in the present.

- In historical analysis and portrayals, the analytical challenge is to understand what part of a course of events is attributable to conscious human actions and decisions, what part is shaped by the combination of given circumstances in which the human actors had to act, and what exactly is the relationship between them (the link between the "part" and the "whole").

- Because the ability to prove historical assessments scientifically is limited, ideology, a mind-set or a social mentality about the state of the world typically plays an important role in the perspectives people develop (Mandel refers here to an idea by Lucien Goldmann).[10] With hindsight, it may be possible to trace out accurately why events necessarily developed in the way that they did, and not otherwise. But at the time they are happening, this is usually not, or not completely possible, and the hope (or fear) for a particular future may play an important role (here Mandel refers to the philosophy of Ernst Bloch).[11] In addition, ideology influences whether one looks upon past events as failures or successes (as many historians have noted, history is often rewritten by the victors in great historical battles to cast themselves in an especially positive light). There is no "non-partisan" history-writing in this sense, at best we can say the historian had full regard for the known facts pertaining to the given case and frankly acknowledges his biases.

- "History" in general cannot be simply defined as "the past", because it is also "the past living in the present" and "the future living in the present". Historical thinking is not just concerned with what past events led to the present, but also with those elements from the past which are contained in the present and elements that point to the future. It involves both antecedents and consequents, including future effects. Only on that basis can we define how people can "make history" as a conscious praxis.

- The main reason for studying history is not because we[who?] should assign praise or blame, or simply because it is interesting, but because we need to study past experience to understand the present and the future. History can be seen as a "laboratory", the lab-record of which shows how, under given conditions, people tried to achieve their goals, and what the results of their experimentations were. This can provide insight into what is likely or unlikely to succeed in future. At the very least, each generation has to come to grips with the experience of the previous generation, as well as educating the future generation.

- The theory of historicism according to which the historical process as a whole has an overall purpose or teleology (or "grand design") is rejected. With Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Mandel thought that "'History does nothing... It is people, real, living people who do all that... “history” is not, as it were, a person apart, using people as a means to achieve its own aims; history is nothing but the activity of people pursuing their aims".[12] With the proviso that people did so within given parameters not of their own making, allowing us to identify broad historical movements as determinate processes. The historical process is also not a matter of linear progress according to inevitable stages—both progress and regress can occur, and different historical outcomes are possible depending on what people do.

Perceptions and illusions

According to the theory of parametric determinism, the "human problem" in this context is usually not that human beings lack free choice or free will, or that they cannot in principle change their situation (at least to some extent), but rather is their awareness of the options open to them, and their belief in their own ability to act on them—influenced as they may be, by their ideology, experience and emotions.

Perceptions of what people can change or act upon may vary a great deal, they might overestimate it, or underestimate it. Thus it may take scientific inquiry to find out what perceptions are realistic. By discovering what the determinism is, we can learn better how we can be free. Simply put, we could "bang our head against a wall", but we could also go over the wall, through a door in the wall, or around the wall. At crucial points, humans can "make history" actively with a high awareness of what they are doing, changing the course of history, but they can also "be made by history" to the extent that they passively conform to (or are forced to conform to) a situation which is mostly not of their own making and which they may not understand.

As regards the latter, Mandel referred to the condition of alienation in the sense of a diminished belief in the ability to have control over one's own life, or feeling estranged from one's real nature and purpose in life.[13] People might reify aspects of their situation. They might regard something as inevitable ("God's will") or judge "nothing could be done to prevent it" when the real point is that, for specific reasons, nobody was prepared to do anything about it—something could have been done, but it wasn't. Thus "historical inevitability" can also be twisted into a convenient apology to justify a course of events.

In this process of making choices within a given objective framework of realistic options, plenty of illusions are also possible, insofar as humans may have all kinds of gradations of (maybe false) awareness about their true situation. They may, as Mandel argues, not even be fully aware of what motivates their own actions, quite aside from not knowing fully what the consequences of their actions will be. A revolutionary seeking to overthrow the old order to make way for a new one obviously faces many "unknowns".

Therefore, human action can have unintended consequences, including effects which are completely opposite to what was intended.[14] This means that popular illusions can also shape the outcomes of historical events. If most people believe something to be the case, even although it is not true, this fact can also become a parameter limiting what can happen or influencing what will happen.

Skeptical reply

Because terrible illusions can occur, some historians are skeptical about the ability of people to change the world for the better in any real and lasting way. Postmodernism casts doubt on the existence of progress in history as such—if e.g. Egyptians built the Great Pyramid of Giza in 2500 BC, and Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong landed on the moon in 1969, this represents no progress for humanity.

However, Mandel argued that this skepticism is itself based on perceptions of what people are able to know about their situation and their history. Ultimately, the skeptic believes that it is impossible for people to have sufficient knowledge of a kind that they can really change the human condition for the better, except perhaps in very small ways. It just is what it is. This skeptical view does not necessarily imply a very "deterministic" view of history however; history could also be viewed as an unpredictable chaos or too complex to fathom.

However, most politicians and political activists (including Mandel himself) at least do not believe that history generally is an unpredictable chaos, because in that case their own standpoints would be purely arbitrary and be perceived as purely arbitrary. Usually, they would argue, the chaos is limited in space and time, because in perpetual chaos, human life can hardly continue anyway; in that case, people become reactive beasts. Since people mostly do want to survive, they need some order and predictability. One can understand what really happened in history reasonably well, if one tries. Human beings can understand human experience because they are human, and the more relevant experience they obtain, the better they can understand it.

Conscious human action, Mandel argues, is mainly non-arbitrary and practical, it has a certain "logic" to it even if people are not (yet) fully aware of this. The reality they face is ordered in basic ways, and therefore can be meaningfully understood. Masses of people might go into a "mad frenzy" sometimes that might be difficult to explain in rational terms, but this is the exception, not the rule. What is true is that a situation of chaos and disorder (when nothing in society seems to work properly anymore) can powerfully accentuate the irrational and non-rational aspects of human behaviour. In such situations, people with very unreasonable ideas can rise to power. This is, according to Mandel, part of the explanation of fascism.[15]

Historical latency and the possibilities for change

The concept of parametric determinism has as its corollary the concept of historical latency. It is not just that different historical outcomes are possible, but that each epoch of human history contains quite a few different developmental potentials. The indications of these potentials can be empirically identified, and are not simply a speculation about "what could conceivably happen".

But they are latent factors in the situation, insofar as they will not necessarily be realised or actualised. Their realisation depends on human action, on the recognition of the potential that is there, and the decision to do something about it. Thus, Mandel argues that both socialism and barbarism exist as broad "latent" developmental possibilities within modern capitalist society, even if they are not realised, and whether and which of these will be realised, depends on human choices and human actions.

Effective action to change society, he argues, has to set out from the real possibilities there are for an alternative way of doing things, not from abstract speculations about a better world. Some things are realistically possible, but not just "anything" is possible. The analytical challenge—often very difficult—is therefore to understand correctly what the real possibilities are, and which course of action would have the most fruitful effect. One can do only what one is able to do and no more, but much depends on choices about how to spend one's energies.

Typically in wars and revolutions, when people exert themselves to the maximum and have to improvise, it is discovered that people can accomplish far more than they previously thought they could do (also captured in the saying "necessity is the mother of invention"). The whole way people think is suddenly changed. But in times of cultural pessimism, general exhaustion prevails and people are generally skeptical or cynical about their ability to achieve or change very much at all. If the bourgeoisie beats down the workers and constrains their freedom, so that workers have to work more and harder for less and less pay, pessimistic moods can prevail for quite some time. If, on the other hand, the bourgeois economy is expanding, the mood of society can become euphoric, and people believe that just about anything is possible. A famous leftwing slogan in May 1968 was "tout est possible" ("anything is possible"). Similarly, in the boom of the later 1990s, many people in rich countries believed that all human problems could finally be resolved.

That is just to say that what is possible to achieve can be both pessimistically underestimated and optimistically exaggerated at any time. Truly conservative people will emphasize how little potential there is for change, while rebels, visionaries, progressives and revolutionaries will emphasize how much could be changed. An important role for social scientific inquiry and historiography is therefore to relativise all this, and place it in a more objective perspective by looking at the relevant facts.

Criticisms

While Mandel himself made some successful predictions about the future of world society (for instance, he is famous for predicting at the beginning of the 1960s,[16] like Milton Friedman did, that the postwar economic boom would end at the close of the decade), his Trotskyist critics (including his biographer Jan Willem Stutje) argue, with the benefit of hindsight, that he was far too optimistic and hopeful about the possibility of a workers' revolution in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union during the Mikhail Gorbachev era and after—and more generally, that his historical optimism distorted his political perspectives, so that he became too "certain" about a future that he could not be so certain about, or else crucially ambivalent.[17]

This is arguably a rather shallow criticism insofar as the situation could well have developed in different directions, which is precisely what Mandel himself argued;[18] in politics, one could only try to make the most of the situation at the time, and here pessimism was not conducive to action. But the more substantive criticism is that many of Mandel's future scenarios were simply not realistic, and that in reality things turned out rather differently from what he thought. This raises several questions:[19]

- whether the theory of parametric determinism in history is faulty;

- whether Mandel's application of the theory in his analyses was faulty;

- how much we can really foresee anyway, and what distinguishes forecast from prophecy; and

- whether and how much people learn from history anyway.

In answering these criticisms, Mandel himself would probably have referred to what he often called the "laboratory of history". That is, we can check the historical record, to see who predicted what, the grounds given for the prediction, and the results. On that basis, we can verify empirically what kind of thinking (and what kind of people) will produce the most accurate predictions, and what we can really predict with "usable accuracy". One reason why he favoured Marxism was because he believed it provided the best intellectual tools for predicting the future of society. He often cited Leon Trotsky as an example of a good Marxist able to predict the future. In 1925, Trotsky wrote:

The essence of Marxism consists in this, that it approaches society concretely, as a subject for objective research, and analyzes human history as one would a colossal laboratory record. Marxism appraises ideology as a subordinate integral element of the material social structure. Marxism examines the class structure of society as a historically conditioned form of the development of the productive forces; Marxism deduces from the productive forces of society the inter-relations between human society and surrounding nature, and these, in turn are determined at each historical stage by man’s technology, his instruments and weapons, his capacities and methods for struggle with nature. Precisely this objective approach arms Marxism with the insuperable power of historical foresight.[20]

This may all seem a trivial "academic" or "scholastic" debate, similar to retrospective speculations about "what could have been different", but it has very important implications for the socialist idea of a planned economy. Obviously, if it is not possible to predict much about human behaviour with usable accuracy, then not much economic planning is feasible either—since a plan requires at least some expectation that its result can and will be realised in the future, even if the plan is regularly adjusted for new (and unanticipated) circumstances. In general, Mandel believed that the degree of predictability in human life was very much dependent on the way society itself was organised. If e.g. many producers competed with each other for profits and markets, based on privatized knowledge and business secrets, there was much unpredictability in what would happen. If the producers coordinated their efforts co-operatively, much would be predictable.[21]

A deeper problem, to which Mandel alludes with his book Trotsky: A study in the dynamic of his thought, is that if we regard certain conditions as possible to change for the better, we might be able to change them, even if currently people believe it is impossible—whereas if we regard them as unchangeable, we are unlikely to change them at all, even although they could possibly be changed ( a similar insight occurs in pragmatism).[22] That is, we make things possible, by doing something about them rather than do nothing. This, however, implies that even when we try our best to be objective and realistic about history or anything else, we remain subjects influenced by subjective perceptions or elements of fear, hope, will or faith that defy reason or practicality.

Simply put, it is very difficult to bring scientific truths and political action together, as Marxists aim to do, in such a way that we really change the things we can change for the better to the maximum, and do not try to change things we really cannot change anyway (Marxists call this "the unity of theory and practice"). In other words, the will to change things can involve subjective perceptions of a kind for which even the best historical knowledge may offer no assistance or guide. And all perceptions of "history-making" may inescapably involve ideology, thus—according to skeptics—casting some doubt on the very ability of people to distinguish objectively between what can be changed, and what cannot. The boundary between the two might be rather blurry. This is the basis of Karl Popper's famous philosophy of social change by "small steps" only.

Mandel's reply to this skepticism essentially was to agree that there were always "unknowns" or "fuzzy" areas in human experience; for people to accomplish anything at all or "make their own history", required taking a risk, calculated or otherwise. One could indeed see one's life as a "wager" ultimately staked on a belief, scientifically grounded or otherwise. However, he argued it was one thing to realise all that, but another to say that the "unknowns" are "unknowable". Thus, for good or for ill, "you don't know, what you haven't tried" and more specifically "you don't know, what you haven't tried to obtain knowledge about". The limits of knowledge and human possibilities could not be fixed in advance by philosophy; they had to be discovered through the test of practice. This attitude recalls Marx's famous comment that "All social life is essentially practical. All mysteries which lead theory to mysticism find their rational solution in human practice, and in the comprehension of this practice.".[23] Mandel believed, with Marx, that "ignorance never helped anybody" except those who profited from its existence ("never underestimate human gullibility, including your own").

The general task of revolutionary science was to overcome ignorance about human life, and this could not very well be done by reconciling people with their allegedly "predetermined" fate at every opportunity. We all know we will die eventually, but that says little yet about what we can achieve before that point. Skepticism has its uses, but what those uses are, can only be verified from experience; a universal skepticism would be just as arbitrary as the belief that "anything is possible"—it did not lead to any new experience from which something could be learnt, including learning about the possibilities of human freedom. And such learning could only occur through making conscious choices and decisions within given parameters, i.e. in a non-arbitrary (non-chaotic) environment, permitting at least some predictability and allowing definite experiential conclusions.[24]

Mandel often reiterated that most people do not learn all that much from texts or from history, they learn from their own experience. They might be affected by history without knowing it. But anybody concerned with large-scale social change was almost automatically confronted with the need to place matters in broader historical perspective. One had to understand deeply the limits, consequences and implications of human action. Likewise, politicians making decisions affecting large numbers of people could hardly do without a profound sense of history.

See also

- Bounded rationality

- Determinism

- Dialectics

- Economic determinism

- Historical materialism

- Overdetermination

- Philosophy of History

- Social constructionism

Notes

- ↑ Ernest Mandel, "Die Dialektik von Produktivkraften, Produktionsverhaltenissen und Klassenkampf neben Kategorien der Latenz und des Parametrischen Determinismus in der Materialistischen Geschichtsauffassung". In: Die Versteinerten Verhaltenisse zum tanzen Bringen. Beitrage zur Marxistischen Theorie Heute. Berlin: Dietz Verlag, 1991.

- ↑ Ernest Mandel, "How To Make No Sense of Marx" (1989) in: Analyzing Marxism. New essays on Analytical Marxism, edited by Robert Ware & Kai Nielsen, Canadian Journal of Philosophy, Supplementary Volume 15, 1989, The University of Calgary Press, pp. 105–132.

- ↑ Philippe van Parijs, Evolutionary explanation in the social sciences: an emerging paradigm. Totown (New Jersey): Rowman and Littlefield, 1981.

- ↑ Ernest Mandel, "Partially independent variables and internal logic in classical Marxist economic analysis’", in Social Science Information, vol. 24 no. 3 (1985), pp. 487–88 (reprinted in Ulf Himmelstrand, Interfaces in Economic & Social Analysis, London 1992).[gesd.free.fr/mandel85.pdf]

- ↑ Ernest Mandel, Late Capitalism. London: NLB, 1975, p. 16.

- ↑ Ernest Mandel, Late Capitalism. London: NLB, 1975, p. 17.

- ↑ Shaun P. Hargreaves-Heap and Yanis Varoufakis, Game theory. A critical introduction. (2nd ed.). London: Routledge, 2004. Steve Keen, "My Friend Yanis, The Greek Minister Of Finance." Forbes, 31 january 2015.[1]

- ↑ Howard Sherman, "Marx and determinism". Journal of Economic Issues, Vol. 15 No. 1, 1981, pp. 61–71.

- ↑ Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Part 1

- ↑ Ernest Mandel, "The role of the individual in history: the case of world war two", in: New Left Review I-157, May–June 1986.

- ↑ Ernest Mandel, " Anticipation and Hope as Categories of Historical Materialism", in: Historical materialism, Volume 10, Number 4 / December, 2002.

- ↑ Marx, Karl. "The Holy Family by Marx and Engels". Marxists.org. http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/holy-family/ch06_2.htm#history.

- ↑ Ernest Mandel, "The Marxist theory of alienation", in: International Socialist Review, Vol. 3, No. 31, 1970, pp.19-23, 49-50.[2]

- ↑ Heinz D. Kurz, "Das Problem der nichtintendierten Konsequenzen; Zur Politischen Ökonomie von Karl Marx". Marx-Engels Jahrbuch 2012-13, Internationale Marx-Engels-Stiftung, Berlin: Akademie Verlag GmbH, 2013, pp. 75–122.

- ↑ Ernest Mandel, Introduction to Leon Trotsky, The Struggle Against Fascism in Germany, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, 1971, pp. 9–46.

- ↑ Ernest Mandel, "The economics of neocapitalism". The Socialist Register 1964. London: Merlin Press, 1964, pp. 56-67.[3]

- ↑ Jan-Willem Stutje, Ernest Mandel: a rebel's dream deferred. London: Verso, 2009.

- ↑ Ernest Mandel, introduction to Beyond Perestroika: The Future of Gorbachev's USSR. London: Verso, 1989.

- ↑ Merton, Robert K. (1936). "The Unanticipated Consequences of Purposive Social Action". American Sociological Review 1 (6): 894–904 [pp. 895–896]. doi:10.2307/2084615.

- ↑ Leon Trotsky, “Dialectical Materialism and Science” (1925). New International (New York), Vol.6 No.1, February 1940, pp.24-31.[4]

- ↑ Ernest Mandel, "In Defence of Socialist Planning", New Left Review I/159, September–October 1986.

- ↑ Ernest Mandel, Trotsky: A study in the dynamic of his thought. London: NLB, 1979.

- ↑ Marx, Karl. "Theses On Feuerbach by Karl Marx". Marxists.org. http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/theses/index.htm.

- ↑ Ernest Mandel, The Place of Marxism in history

External links

KSF

KSF