Progressivism

Topic: Philosophy

From HandWiki - Reading time: 18 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 18 min

| Part of the Politics series | ||||||

| Party politics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Political spectrum | ||||||

|

||||||

| Party platform | ||||||

| Party organization | ||||||

| Party Leadership | ||||||

| Party system | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Coalition | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Lists | ||||||

| Politics portal | ||||||

Progressivism is a political philosophy that holds that it is possible to improve human societies through political reform or through government mandates. As a political movement, progressivism seeks to advance the human condition through social reform based on purported advancements in science, technology, and social organization.[1] Adherents hold that progressivism has universal application and endeavor to spread this idea to human societies everywhere. Progressivism arose during the Age of Enlightenment out of the belief that civility in Europe was improving due to the application of new empirical knowledge to the governance of society.[2]

In modern political discourse, progressivism gets often associated with social liberalism,[3][4][5] a left-leaning type of liberalism.

History

From the Enlightenment to the Industrial Revolution

Immanuel Kant identified progress as being a movement away from barbarism toward civilization.[6] 18th-century philosopher and political scientist Marquis de Condorcet predicted that political progress would involve the disappearance of slavery, the rise of literacy, the lessening of sex inequality, prison reforms which at the time were harsh, and the decline of poverty.[7]

Modernity or modernisation was a key form of the idea of progress as promoted by classical liberals in the 19th and 20th centuries, who called for the rapid modernisation of the economy and society to remove the traditional hindrances to free markets and the free movements of people.[8]

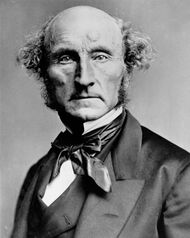

In the late 19th century, a political view rose in popularity in the Western world that progress was being stifled by vast economic inequality between the rich and the poor, minimally regulated laissez-faire capitalism with out-of-control monopolistic corporations, intense and often violent conflict between capitalists and workers, with a need for measures to address these problems.[9] Progressivism has influenced various political movements. Social liberalism was influenced by British liberal philosopher John Stuart Mill's conception of people being "progressive beings."[10] British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli developed progressive conservatism under one-nation Toryism.[11][12]

In France, the space between social revolution and the socially conservative laissez-faire centre-right was filled with the emergence of radicalism which thought that social progress required anti-clericalism, humanism, and republicanism. Especially anti-clericalism was the dominant influence on the centre-left in many French- and Romance-speaking countries until the mid-20th century. In Imperial Germany, Chancellor Otto von Bismarck enacted various progressive social welfare measures out of paternalistic conservative motivations to distance workers from the socialist movement of the time and as humane ways to assist in maintaining the Industrial Revolution.[13]

In 1891, the Roman Catholic Church encyclical Rerum novarum issued by Pope Leo XIII condemned the exploitation of labor and urged support for labor unions and government regulation of businesses in the interests of social justice while upholding the property right and criticising socialism.[14] A progressive Protestant outlook called the Social Gospel emerged in North America that focused on challenging economic exploitation and poverty and, by the mid-1890s, was common in many Protestant theological seminaries in the United States.[15]

Early 20th-century progressivism included support for American engagement in World War I and the creation of and participation in the League of Nations,[16][17] compulsory sterilisation in Scandinavia,[18] and eugenics in Great Britain,[19] and the temperance movement.[20][21] Progressives believed that progress was stifled by economic inequality, inadequately regulated monopolistic corporations, and conflict between workers and elites, arguing that corrective measures were needed.[22]

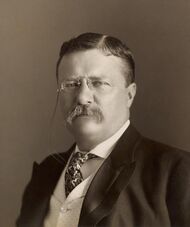

Contemporary mainstream political conception of the philosophy

In the United States, progressivism began as an intellectual rebellion against the political philosophy of Constitutionalism[23] as expressed by John Locke and the founders of the American Republic, whereby the authority of government depends on observing limitations on its just powers.[24] What began as a social movement in the 1890s grew into a popular political movement referred to as the Progressive era; in the 1912 United States presidential election, all three U.S. presidential candidates claimed to be progressives. While the term progressivism represents a range of diverse political pressure groups, not always united, progressives rejected social Darwinism, believing that the problems society faced, such as class warfare, greed, poverty, racism and violence, could best be addressed by providing good education, a safe environment, and an efficient workplace. Progressives lived mainly in the cities, were college educated, and believed in a strong central government.[25] President Theodore Roosevelt of the Republican Party and later the Progressive Party declared that he "always believed that wise progressivism and wise conservatism go hand in hand."[26]

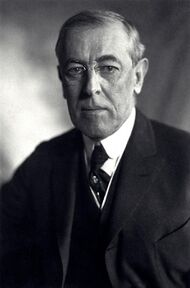

President Woodrow Wilson was also a member of the American progressive movement within the Democratic Party. Progressive stances have evolved. Imperialism was a controversial issue within progressivism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly in the United States, where some progressives supported American imperialism while others opposed it.[27] In response to World War I, President Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points established the concept of national self-determination and criticised imperialist competition and colonial injustices. Anti-imperialists supported these views in areas resisting imperial rule.[28]

During the period of acceptance of economic Keynesianism (the 1930s–1970s), there was widespread acceptance in many nations of a large role for state intervention in the economy. With the rise of neoliberalism and challenges to state interventionist policies in the 1970s and 1980s, centre-left progressive movements responded by adopting the Third Way, which emphasised a major role for the market economy.[29] There have been social democrats who have called for the social-democratic movement to move past Third Way.[30] Prominent progressive conservative elements in the British Conservative Party have criticised neoliberalism.[31]

In the 21st century, progressives continue to favour public policy that they theorise will reduce or lessen the harmful effects of economic inequality as well as systemic discrimination such as institutional racism; to advocate for social safety nets and workers' rights; and to oppose corporate influence on the democratic process. The unifying theme is to call attention to the negative impacts of current institutions or ways of doing things and to advocate for social progress, i.e., for positive change as defined by any of several standards such as the expansion of democracy, increased egalitarianism in the form of economic and social equality as well as improved well being of a population. Proponents of social democracy have identified themselves as promoting the progressive cause.[32]

Types

Cultural progressivism

Progressivism, in the general sense, mainly means social and cultural progressivism. There term cultural liberalism is similar, and is used substantially similarly.[33] However, cultural liberals and progressives may differ in positions on cultural issues such as minority rights, social justice,[citation needed] and political correctness.[34][original research?]

Unlike progressives in a broader sense, some cultural progressives may be economically centrist, conservative, or politically libertarian. The Czech Pirate Party is classified as a (cultural or social) progressive party,[35] but it calls itself "economically centrist and socially liberal".[36]

Economic progressivism

Economic progressivism is a term used to distinguish it from progressivism in cultural fields. Economic progressives' views are often rooted in the concept of social justice and aim to improve the human condition through government regulation, social protections and the maintenance of public goods.[37]

Some economic progressives may show center-right views on cultural issues. These movements are related to communitarian conservative movements such as Christian democracy and one-nation conservatism.[38][39]

Techno progressivism

Progressive parties or parties with progressive factions

Current parties

Argentina: Frente de Todos (factions)[40][41][42]

Argentina: Frente de Todos (factions)[40][41][42] Australia: Australian Greens,[43] Reason Party, Australian Labor Party (factions)

Australia: Australian Greens,[43] Reason Party, Australian Labor Party (factions) Brazil: Workers' Party,[44] Brazilian Socialist Party (factions),[45] Democratic Labour Party,[46] Socialism and Liberty Party[47]

Brazil: Workers' Party,[44] Brazilian Socialist Party (factions),[45] Democratic Labour Party,[46] Socialism and Liberty Party[47] Canada: Liberal Party of Canada (factions),[48][49][50][51] New Democratic Party

Canada: Liberal Party of Canada (factions),[48][49][50][51] New Democratic Party Chile: Social Convergence,[52] Liberal Party of Chile

Chile: Social Convergence,[52] Liberal Party of Chile Colombia: Humane Colombia

Colombia: Humane Colombia Czech Republic: Czech Pirate Party[35][53]

Czech Republic: Czech Pirate Party[35][53] France: Radical Party of the Left, New Deal[54]

France: Radical Party of the Left, New Deal[54] Germany: Alliance 90/The Greens

Germany: Alliance 90/The Greens Greece: Syriza[55][56][57][58]

Greece: Syriza[55][56][57][58] Hungary: Democratic Coalition

Hungary: Democratic Coalition India: Indian National Congress, Aam Aadmi Party, Bahujan Samaj Party, Trinamool Congress[59]

India: Indian National Congress, Aam Aadmi Party, Bahujan Samaj Party, Trinamool Congress[59] Italy: Possible, Green Europe

Italy: Possible, Green Europe Indonesia: Indonesian Solidarity Party,[60] Green Party of Indonesia[61]

Indonesia: Indonesian Solidarity Party,[60] Green Party of Indonesia[61] Japan: Social Democratic Party, Japanese Communist Party,[62][63][64] Reiwa Shinsengumi[65]

Japan: Social Democratic Party, Japanese Communist Party,[62][63][64] Reiwa Shinsengumi[65] Kosovo: Vetëvendosje

Kosovo: Vetëvendosje Mexico: Morena, Party of the Democratic Revolution, Citizens' Movement

Mexico: Morena, Party of the Democratic Revolution, Citizens' Movement Netherlands: Democrats 66, GroenLinks,[66][67][68][69][70] PvdA[67][68][69][70][71]

Netherlands: Democrats 66, GroenLinks,[66][67][68][69][70] PvdA[67][68][69][70][71] Pakistan: Pakistan Peoples Party

Pakistan: Pakistan Peoples Party Peru: Purple Party

Peru: Purple Party Philippines: Akbayan[72]

Philippines: Akbayan[72] Poland: Polish Initiative, Your Movement

Poland: Polish Initiative, Your Movement Portugal: Socialist Party, Left Bloc, People Animals Nature,[73]

Portugal: Socialist Party, Left Bloc, People Animals Nature,[73] Romania: Save Romania Union, Democracy and Solidarity Party, Volt Romania, PRO Romania

Romania: Save Romania Union, Democracy and Solidarity Party, Volt Romania, PRO Romania Russia: Yabloko[74]

Russia: Yabloko[74] Serbia: Party of the Radical Left

Serbia: Party of the Radical Left Slovakia: Progressive Slovakia

Slovakia: Progressive Slovakia South Korea: Justice Party, Progressive Party,[75][76] Mirae Party

South Korea: Justice Party, Progressive Party,[75][76] Mirae Party Spain: Unidas Podemos, Spanish Socialist Worker's Party,[55][77] Más Madrid,[78][79] Sumar

Spain: Unidas Podemos, Spanish Socialist Worker's Party,[55][77] Más Madrid,[78][79] Sumar Taiwan: Democratic Progressive Party,[80][81] New Power Party, Taiwan People's Party

Taiwan: Democratic Progressive Party,[80][81] New Power Party, Taiwan People's Party Thailand:Thai Liberal Party,[82] Move Forward Party

Thailand:Thai Liberal Party,[82] Move Forward Party Turkey: Republican People's Party

Turkey: Republican People's Party United Kingdom: Green Party of England and Wales,[83] Labour Party (factions), Scottish National Party, Plaid Cymru, Social Democratic and Labour Party

United Kingdom: Green Party of England and Wales,[83] Labour Party (factions), Scottish National Party, Plaid Cymru, Social Democratic and Labour Party United States: Democratic Party (factions),[34][84][85] Green Party of the United States[86]

United States: Democratic Party (factions),[34][84][85] Green Party of the United States[86] Venezuela: Popular Will

Venezuela: Popular Will

Former parties

Argentina: Front for Victory[87]

Argentina: Front for Victory[87] Canada: Progressive Party of Canada

Canada: Progressive Party of Canada France: Movement Party,[88] Opportunist Republicans

France: Movement Party,[88] Opportunist Republicans Hong Kong: Demosisto

Hong Kong: Demosisto Japan: Japan Socialist Party

Japan: Japan Socialist Party Netherlands: Free-thinking Democratic League[89]

Netherlands: Free-thinking Democratic League[89] New Zealand: Jim Anderton's Progressive Party

New Zealand: Jim Anderton's Progressive Party Poland: Spring

Poland: Spring Romania: Romanian Social Party, National Union for the Progress of Romania

Romania: Romanian Social Party, National Union for the Progress of Romania South Korea: Progressive Party (1956), Democratic Labor Party,[90][91] New Progressive Party, Unified Progressive Party

South Korea: Progressive Party (1956), Democratic Labor Party,[90][91] New Progressive Party, Unified Progressive Party United States: Progressive Party (1912), Progressive Party (1924), Progressive Party (1948)

United States: Progressive Party (1912), Progressive Party (1924), Progressive Party (1948)

See also

- Affirmative action

- Democracy

- Democratic socialism

- Economic progressivism

- Egalitarianism

- Green politics

- Left-libertarianism

- Left-wing nationalism

- Left-wing politics

- Left-wing populism

- Liberal socialism

- Liberalism

- Managerial state

- Modern liberalism in the United States

- Progressive conservatism

- Progressive Era

- Progressive Party

- Progressive tax

- Radicalism (historical)

- Reformist party (Japan)

- Revisionism (Marxism)

- Secular liberalism

- Secularism

- Techno-progressivism

- Transhumanism

- Transhumanist politics

References

Citations

- ↑ "Progressivism in English". Oxford English Dictionary. https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/progressivism.

- ↑ Harold Mah. Enlightenment Phantasies: Cultural Identity in France and Germany, 1750–1914. Cornell University. (2003). p. 157.

- ↑ Klaus P. Fischer, ed (2007). America in White, Black, and Gray: A History of the Stormy 1960s. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 39.

- ↑ Great Courses, ed (2014). The Modern Political Tradition: Episode 17: Progressivism and New Liberalism. Great Courses.[ISBN missing]

- ↑ Helen Hardacre, ed (2021). Japanese Constitutional Revisionism and Civic Activism. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 136, 162.[ISBN missing]

- ↑ Kant, Immanuel; Reiss, Hans Siegbert (1991). "Kant: political writings". Cambridge [England]; New York: Cambridge University Press. https://archive.org/details/kantpoliticalwri00kant/page/41/mode/2up.

- ↑ Nisbet, Robert (1980). History of the Idea of Progress. New York: Basic Books. ch 5

- ↑ Joyce Appleby; Lynn Hunt; Margaret Jacob (1995). Telling the Truth about History. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 78. ISBN 9780393078916. https://books.google.com/books?id=O0aCcnVcbZcC&pg=78.

- ↑ Nugent, Walter (2010). Progressivism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 2. ISBN 9780195311068.

- ↑ Alan Ryan. The Making of Modern Liberalism. p. 25.

- ↑ Patrick Dunleavy, Paul Joseph Kelly, Michael Moran. British Political Science: Fifty Years of Political Studies. Oxford, England; Malden, Massachusetts: Wiley-Blackwell, 2000. pp. 107–108. [ISBN missing]

- ↑ Robert Blake. Disraeli. Second Edition. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode (Publishers) Ltd, 1967. p. 524.[ISBN missing]

- ↑ Union Contributions to Labor Welfare Policy and Practice: Past, Present, and Future. Routledge, 16, 2013. p. 172. [ISBN missing]

- ↑ Faith Jaycox. The Progressive Era. New York: Infobase Publishing, 2005. p. 85.

- ↑ Charles Howard Hopkins, The Rise of the Social Gospel in American Protestantism, 1865–1915 (1940). [page needed][ISBN missing]

- ↑ Freeden, Michael (2005). Liberal Languages: Ideological Imaginations and Twentieth-Century Progressive Thought. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 144–165. ISBN 9780691116778. https://books.google.com/books?id=1Lpu8wwvA1AC&pg=144.

- ↑ Ambrosius, Lloyd E. (April 2006). "Woodrow Wilson, Alliances, and the League of Nations". The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 5 (2): 139–165. doi:10.1017/S153778140000298X.

- ↑ Roll-Hansen, Nils (1989). "Geneticists and the Eugenics Movement in Scandinavia". The British Journal for the History of Science 22 (3): 335–346. doi:10.1017/S0007087400026194. PMID 11621984.

- ↑ Leonard, Thomas (2005). "Retrospectives: Eugenics and Economics in the Progressive Era". Journal of Economic Perspectives 19 (4): 207–224. doi:10.1257/089533005775196642. https://www.princeton.edu/~tleonard/papers/retrospectives.pdf. Retrieved 2017-10-22.

- ↑ James H. Timberlake, Prohibition and the Progressive Movement, 1900–1920 (1970)[page needed][ISBN missing]

- ↑ "Prohibition: A Case Study of Progressive Reform". Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/presentationsandactivities/presentations/timeline/progress/prohib/.

- ↑ Nugent, Walter (2010). Progressivism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. pp. 2. ISBN 9780195311068.

- ↑ Waluchow, Wil (17 August 2018). "Constitutionalism". in Zalta, Edward N.. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2018/entries/constitutionalism/.

- ↑ Watson, Bradley (2020). Progressivism : the strange history of a radical idea. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press. p. 11. ISBN 9780268106973.

- ↑ "The Progressive Era (1890–1920)". The Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project. . Retrieved 31 September 2014.

- ↑ Lurie, Jonathan (2012). William Howard Taft: The Travails of a Progressive Conservative. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 196.

- ↑ Nugent, Walter (2010). Progressivism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. pp. 33. ISBN 9780195311068.

- ↑ Reconsidering Woodrow Wilson: Progressivism, Internationalism, War, and Peace. p. 309. [ISBN missing]

- ↑ Jane Lewis, Rebecca Surender. Welfare State Change: Towards a Third Way?. Oxford University Press, 2004. pp. 3–4, 16. [ISBN missing]

- ↑ After the Third Way: The Future of Social Democracy in Europe. I.B. Taurus, 2012. p. 47. [ISBN missing]

- ↑ Hugh Bochel. The Conservative Party and Social Policy. The Policy Press, 2011. p. 108. [ISBN missing]

- ↑ Henning Meyer, Jonathan Rutherford. The Future of European Social Democracy: Building the Good Society. Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. p. 108. [ISBN missing]

- ↑ Nancy L. Cohen, ed (2012). Delirium: The Politics of Sex in America. Catapult. ISBN 9781619020962. https://books.google.com/books?id=J90REAAAQBAJ&dq=%22Cultural+liberal%22+Cultural+progressive&pg=PT145. "When the going got tough, the economic progressives got going back to the Reagan days when the cultural progressives were to blame. Clinton's presidential campaign had "signaled cultural moderation and articulated the pocketbook frustrations of ordinary people," Robert Kuttner, editor of The American Prospect ventured. "But in office, he seemed a cultural liberal who failed to produce on economics.""

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Ball, Molly. "The Battle Within the Democratic Party". https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2013/12/the-battle-within-the-democratic-party/282235/.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Slawek Blitch. Finally, a healthy dose of anti-establishment. politicalcritique.org. 8 January 2018.

- ↑ "Piráti chtějí vést liberální politický střed a v květnu získat 20 procent, zaznělo na fóru v Táboře" (in Czech). ČT24. 19 January 2019.

- ↑ "The Origins and Evolution of Progressive Economics".

- ↑ "Did you know there's a third party based on Catholic teaching?". Catholic News Agency. 12 October 2016. https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/news/did-you-know-theres-a-third-party-based-on-catholic-teaching-45272. "Politically, we would be considered center-right on social issues"

- ↑ "New political party says its roots are in Catholic Social Teaching". 26 November 2018. https://cruxnow.com/interviews/2018/11/new-political-party-says-its-roots-are-in-catholic-social-teaching/. "I was working on my doctoral dissertation largely concerning difficulties and opportunities for socially conservative, economically progressive movements, and desired to get involved in such movements ... and was glad to see that ASP was interested in applying such ways of thinking to contemporary issues."

- ↑ "La llamativa definición política de Alberto Fernández: "Soy de la rama del liberalismo progresista peronista"". Clarín. 19 July 2019. https://www.clarin.com/politica/llamativa-definicion-politica-alberto-fernandez-rama-liberalismo-progresista-peronista_0_Ym3yLMfHX.html.

- ↑ "Juan Grabois lanza el Frente Patria Grande que lideraría Cristina Kirchner" (in es). Perfil. 27 October 2018. https://www.perfil.com/noticias/politica/juan-grabois-lanza-el-frente-patria-grande-que-liderara-cristina-fernandez.phtml.

- ↑ "Alberto Fernández: "Soy más hijo de la cultura hippie que de las veinte verdades peronistas"". 12 April 2020. https://www.perfil.com/noticias/periodismopuro/alberto-fernandez-soy-mas-hijo-de-la-cultura-hippie-que-de-las-veinte-verdades-peronistas.phtml.

- ↑ Lopez, Daniel; Bandt, Adam (3 September 2021). "Australian Greens Are Building a Movement to End Neoliberalism". https://www.jacobinmag.com/2021/09/australia-greens-green-new-deal-gnd-elections.

- ↑ Liisa L. North, Timothy D. Clark, ed (2017). Dominant Elites in Latin America: From Neo-Liberalism to the 'Pink Tide'. Springer. p. 212. ISBN 9783319532554. https://books.google.com/books?id=WNsxDwAAQBAJ&dq=Brazil+%22progressive+Workers%27+Party%22&pg=PA212. "In Brazil, as Simone Bohn makes straightforward (Chap. 3), the progressive Workers' Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores, PT) governments did not threaten the power of the national elite or landlord class; ..."

- ↑ "A trajetória do PSB, o Partido que quer lançar Joaquim Barbosa à Presidência", BBC News Brasil, https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/brasil-43887498

- ↑ "O Que é ser progressist?", BBC News Brasil, https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/brasil-62491258

- ↑ O que pensam os partidos progressistas sobre o "Efeito Lula", 17 March 2021, https://www.brasildefato.com.br/2021/03/17/o-que-pensam-os-partidos-progressistas-sobre-o-efeito-lula

- ↑ Alvin Finkel (2012). Our Lives: Canada after 1945: Second Edition. James Lorimer & Company. p. 5. "... capitalism and a wise federal bureaucracy presided over by a progressive Liberal party with intelligent leaders."

- ↑ Robert Harris (2018). Song of a Nation: The Untold Story of Canada's National Anthem. McClelland & Stewart.

- ↑ "Trudeau made pushing his agenda more complicated with a failed bid for majority". CBC. 21 September 2021. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/hall-election-2021-analysis-1.6183615.

- ↑ Emmett Macfarlane (2021). Dilemmas of Free Expression. University of Toronto Press. p. 317.

- ↑ "El pinochetista Kast y el progresista Boric definirán la presidencia el 19 de diciembre elecciones en Chile". https://www.ambito.com/mundo/chile/el-pinochetista-kast-y-el-progresista-boric-definiran-la-presidencia-el-19-diciembre-elecciones-n5321694.

- ↑ Katerina Safarikova. "Czechs Eye 'Symbolic' Pirate Breakthrough in Europe". /balkaninsight.com. 21 May 2019.

- ↑ "Notre charte fondatrice" (in fr). https://www.nouvelledonne.fr/nos-valeurs/.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Gregor Fitzi, ed (2018). Populism and the Crisis of Democracy: Volume 3: Migration, Gender, and Religion. Routledge. ISBN 9781351608916. https://books.google.com/books?id=nGNwDwAAQBAJ&dq=progressive+SYRIZA&pg=PT44. "Progressive groups such as Syriza and Podemos6 tend, on the contrary, to show solidarity towards migrants and refugees, as in general being the weakest components of the society. The Five Star Movement that defines itself as neither ..."

- ↑ Christopher Chase-Dunn, Paul Almeida, ed (2020). Global Struggles and Social Change: From Prehistory to World Revolution in the Twenty-First Century. JHU Press. p. 133. ISBN 9781421438634. https://books.google.com/books?id=nbD5DwAAQBAJ&dq=progressive+Syriza&pg=PA133. "The Arab Spring, the Latin American Pink Tide, the Indignados in Spain, the Occupy movement, the rise of progressive social movement– based parties in Spain (Podemos) and in Greece (Syriza), and the spike in mass protests in 2011 and ..."

- ↑ Prebble Q. Ramswell, ed (2017). Euroscepticism and the Rising Threat from the Left and Right: The Concept of Millennial Fascism. Lexington Books. p. 86. ISBN 9781498546041. https://books.google.com/books?id=_wNBDwAAQBAJ&dq=progressive+Syriza&pg=PA86. "SYRIZA massively scooped up the votes of leftist, progressive, socially liberal young people, as well as the trade union voters, not specifically aligned with the Communist Party, to gain 52 seats."

- ↑ Ken McMullen, Martin McQuillan, ed (2015). Oxi: An Act of Resistance: The Screenplay and Commentary, Including interviews with Derrida, Cixous, Balibar, and Negri. Lexington Books. p. 12. ISBN 9781783482702. https://books.google.com/books?id=XOHaDwAAQBAJ&dq=progressive+SYRIZA&pg=PA12. "The choice to be made for Syriza is between fidelity to a progressive social agenda and retaining Greece's place within a community of nations tied together by a commitment to a neoliberal global economy. The skill with which they ..."

- ↑ "'India's soul at stake': Bengalis vote in divisive election". The Guardian. 26 March 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/mar/26/india-soul-at-stake-west-bengalis-vote-in-divisive-election-modi-bjp. "The TMC has implemented a progressive development agenda, but it has also been mired in accusations of corruption and thuggery."

- ↑ "PSI: Gerakan Progresif Baru?" (in id). pinter politik. 24 August 2017. https://www.pinterpolitik.com/in-depth/psi-gerakan-progresif-baru/?amp=1.

- ↑ "Mengenal Partai Hijau Indonesia: Suarakan Isu Lingkungan, Anti Mengultuskan Pemimpin" (in id). 8 February 2023. https://mojok.co/kotak-suara/mengenal-partai-hijau-indonesia-suarakan-isu-lingkungan-anti-mengultuskan-pemimpin/.

- ↑ Matthew Allen, Rumi Sakamoto, ed (2007). Popular Culture, Globalization and Japan. Routledge. "... capturing 295 seats in the Diet. Progressive parties like the Japanese Communist Party and Social Democratic Party, ..."

- ↑ Willy Jou, Masahisa Endo, ed (2016). EGenerational Gap in Japanese Politics: A Longitudinal Study of Political Attitudes and Behaviour. Springer. p. 29. ISBN 9781137503428. https://books.google.com/books?id=BDelDAAAQBAJ&dq=progressive+%22Japanese+Communist+Party%22&pg=PA29. "Conventional wisdom, still dominant in media and academic circles, holds that the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and the Japanese Communist Party (JCP) occupy the conservative and progressive ends of the ideological spectrum, ..."

- ↑ ""선제공격 능력 갖추자" 日정부 주장에…"시대착오적" 비판". Edaily. 13 November 2021. https://www.edaily.co.kr/news/Read?newsId=01439926629245392&mediaCodeNo=257. "... 개헌에 반대해 온 진보 성향의 일본공산당은 "적 기지에 대한 공격력을 갖추더라도 상대국의 지하나 이동발사대 등 미사일 위치를 모두 파악하고 파괴하는 것은 불가능하다"며 ..."

- ↑ Brasor, Philip (20 July 2019). "Citizen campaigns seek to increase voter turnout in Upper House election". The Japan Times. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2019/07/20/national/media-national/citizen-campaigns-seek-increase-voter-turnout-upper-house-election/.

- ↑ "GroenLinks (GL)" (in nl). https://www.parlement.com/id/vh8lnhrouwy1/groenlinks_gl.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 GroenLinks. "EEN PROGRESSIEF OPPOSITIEAKKOORD". https://groenlinks.nl/een-progressief-oppositieakkoord.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 GroenLinks. "PVDA EN GROENLINKS SLUITEN PROGRESSIEF OPPOSITIEAKKOORD". https://groenlinks.nl/nieuws/pvda-en-groenlinks-sluiten-progressief-oppositieakkoord.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 ProDemos NL. "Indeling van partijen". https://prodemos.nl/kennis/informatie-over-politiek/politieke-partijen/indeling-van-partijen/.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 "Progressief Oppositieakkoord" (in nl). https://www.pvda.nl/progressief-oppositieakkoord/.

- ↑ "Partij van de Arbeid (PvdA)" (in nl). https://www.parlement.com/id/vh8lnhrouwxn/partij_van_de_arbeid_pvda.

- ↑ "About Akbayan – Akbayan Party List" (in en-gb). https://akbayan.org.ph/who-we-are.

- ↑ The politics of Portugal – who are the parties?, https://www.theportugalnews.com/news/2022-01-25/the-politics-of-portugal-who-are-the-parties/64840

- ↑ Lewis, Paul G. (2018). Party Development and Democratic Change in Post-Communist Europe: The First Decade. Taylor & Francis US. ISBN 9780714681740. https://books.google.com/books?id=jyQ3nR6Jls8C&q=progressivism+yabloko+russia&pg=PA160.

- ↑ "Minjung Party press conference". Yonhap News Agency. 11 October 2018. https://en.yna.co.kr/view/PYH20200518227800320. "Members of the progressive Minjung Party hold a press conference in front of former President Chun Doo-hwan's home in Seoul on May 18, 2020."

- ↑ "South Korea Backtracks on Easing Sanctions After Trump Comment". The New York Times. 11 October 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/11/world/asia/south-korea-north-sanctions-trump.html. ""The dog barks, but the caravan moves on," Lee Eun-Hae, a spokeswoman at the minor progressive Minjung Party, said in a statement about Mr. Trump and closer relations with North Korea."

- ↑ Sebastián Royo, ed (2020). Why Banks Fail: The Political Roots of Banking Crises in Spain. Springer Nature. p. 298. ISBN 9781137532282. https://books.google.com/books?id=iM7tDwAAQBAJ&dq=progressive+%22Unidas+Podemos%22&pg=PA298. "As of January 2020 (the time of writing), a new leftist government coalition between the Socialist Party and the leftist populist Unidas Podemos that emerged from the November 2019 election is coming to power with a progressive agenda ..."

- ↑ "Errejón pide a Gabilondo centrarse en lo importante, una mayoría progresista" (in Spanish). La Vanguardia. EFE (Madrid). 24 May 2019. https://www.lavanguardia.com/politica/20190524/462432376624/errejon-pide-a-gabilondo-centrarse-en-lo-importante-una-mayoria-progresista.html.

- ↑ "The Center Cannot Hold in Spain, but Can the Left Take Advantage?". The Nation. 3 May 2021. https://www.thenation.com/article/world/spain-madrid-elections/.

- ↑ "Democracy prevails in Taiwan". Taiwan News. 12 January 2020. https://www.taiwannews.com.tw/en/news/3855810.

- ↑ Kuo, Yu-Ying, ed (2018). Policy Analysis in Taiwan. Policy Press. "The Democratic Progressive Party, founded in 1986, is a progressive and liberal political party in Taiwan."

- ↑ Nidhi Eoseewong (2018-05-08). "Nidhi Eoseewong: An open letter to Pheu Thai". prachatai. https://prachatai.com/english/node/7737.

- ↑ "Green Party of England and Wales elects new leaders". European Green Party. https://europeangreens.eu/news/green-party-england-and-wales-elects-new-leaders.

- ↑ Joseph M. Hoeffel, ed (2014). Fighting for the Progressive Center in the Age of Trump. ABC-CLIO.

- ↑ Chotiner, Isaac (2 March 2020). "How Socialist Is Bernie Sanders?" (in en-us). The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/news/q-and-a/how-socialist-is-bernie-sanders. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ↑ Denisha Jones, Jesse Hagopian, ed (2020). Black Lives Matter at School: An Uprising for Educational Justice. Haymarket Books. ISBN 9781642595307. https://books.google.com/books?id=x_8FEAAAQBAJ&dq=%22progressive+Green+Party%22+United+States&pg=PT99. "She later ran as a New York State lieutenant gubernatorial candidate on a progressive Green Party platform"

- ↑ Daniel K. Lewis, ed (2014). The History of Argentina, 2nd Edition. ABC-CLIO. p. 193. ISBN 9781610698610. https://books.google.com/books?id=lZLgBQAAQBAJ&dq=progressive++FpV+Argentina&pg=PA193. "Progressive decrees, exemplified by the government's legalization of same-sex marriage in July, depicted the FPV as progressive. Behind the scenes, Kirchner promoted 'La Campora," and Peronist youth organization."

- ↑ Rémond, René (1966). University of Pennsylvania Press. ed. The Right Wing in France: From 1815 to de Gaulle.

- ↑ David Broughton (1999). Changing Party Systems in Western Europe. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 166–. ISBN 9781855673281. https://books.google.com/books?id=NkDNoNiBEjUC&pg=PA166. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ↑ Kim, Sunhyuk (2007), "Civil society and democratization in Korea", Korean Society (Taylor & Francis): p. 65, ISBN 9780203966648, https://books.google.com/books?id=BQ5uA3KW1ewC&q=%22Democratic+Labor+Party%22+korea+progressive&pg=PA65

- ↑ Chang, Yun-Shik (2008), "Left and right in South Korean politics", Korea Confronts Globalization (Taylor & Francis): p. 176, ISBN 9780203931141, https://books.google.com/books?id=3-HxKjWqMEMC&q=%22Democratic+Labor+Party%22+korea+progressive&pg=PA176

Sources

- Dudley, Larkin Sims. "Enduring narratives from progressivism." International Journal of Organization Theory & Behavior 7.3 (2003): 315-340.

- Eisenach, Eldon J., ed. Social and Political Thought of American Progressivism. (Hackett Publishing, 2006).

- Frohman, Larry. "The Break-Up of the Poor Laws—German Style: Progressivism and the Origins of the Welfare State, 1900–1918." Comparative Studies in Society and History 50.4 (2008): 981-1009.

- Jackson, Ben. "Equality and the British Left: A study in progressive political thought, 1900-64." in Equality and the British Left (2013)

- Kloppenberg, James T. Uncertain Victory: Social Democracy and Progressivism in European and American Thought, 1870–1920. Oxford University Press, US, 1988. ISBN 0195053044.

- Lakoff, George. Don't Think of an Elephant: Know Your Values and Frame the Debate. Chelsea Green Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1931498717.

- Link, Arthur S. and McCormick, Richard L. Progressivism (American History Series). Harlan Davidson, 1983. ISBN 0882958143.

- McGerr, Michael. A Fierce Discontent: The Rise and Fall of the Progressive Movement in America, 1870–1920. 2003.

- Nugent, Walter. Progressivism: A very short introduction (Oxford University Press, 2009).

- Petrow, Stefan. "Progressivism in Australia: the case of John Daniel Fitzgerald, 1900-1922." Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society 90.1 (2004): 53-74.

- Sawyer, Stephen, and William J. Novak. "Emancipation and the creation of modern liberal states in America and France." Journal of the civil war era 3.4 (2013): 467-500. online[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- Schutz, Aaron. Social Class, Social Action, and Education: The Failure of Progressive Democracy. Palgrave, Macmillan, 2010. ISBN 9780230105911.

- Tröhler, Daniel. Progressivism. In: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. Oxford University Press, 2017.

External links

- Progressivism – entry at the Encyclopædia Britannica

|

KSF

KSF