The First and Last Freedom

Topic: Philosophy

From HandWiki - Reading time: 14 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 14 min

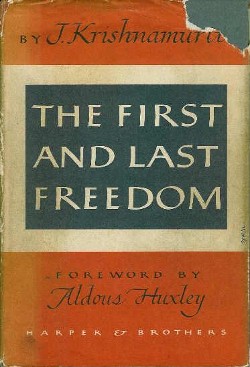

First US edition 1954 | |

| Author | Jiddu Krishnamurti |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom, United States |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Philosophy |

| Published |

|

| Media type |

|

| Pages | 288 (1st edition) |

| ISBN | 978-0-06-204529-4 (1st digital edition) |

| OCLC | 964457 (1st US edition) |

| LC Class | B133.K7 F5 |

The First and Last Freedom is a book by 20th-century India n philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895–1986). Originally published in 1954 with a comprehensive foreword by Aldous Huxley, it was instrumental in broadening Krishnamurti's audience and exposing his ideas. It was one of the first Krishnamurti titles in the world of mainstream, commercial publishing, where its success helped establish him as a viable author. The book also established a format frequently used in later Krishnamurti publications, in which he presents his ideas on various interrelated issues, followed by discussions with one or more participants. As of 2022 several editions of the work had been published, in print and digital media.

Background

Following his dismantling of the World Teacher Project in Template:Dash year, Jiddu Krishnamurti embarked on a new international speaking career as an independent, unconventional philosopher.[1] During World War II he remained at his residence in Ojai, California, in relative isolation.[2] English author Aldous Huxley lived nearby; he met Krishnamurti in 1938,[3] and the two men became close friends.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Huxley encouraged Krishnamurti to write,[4] and also introduced his work to Harper, Huxley's own publisher. This eventually led to the addition of Krishnamurti in the publisher's roster of authors; [5] until that time Krishnamurti works were published by small or specialist presses, or in-house by a variety of Krishnamurti-related organizations.[6][7]

About the work

The thinker comes into being through thought;

Like the great majority of Krishnamurti texts, the book consists of edited excerpts from his public talks and discussions; it includes examinations of subjects that were, or became, recurrent themes in his exposition: ({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) the nature of the self – and of belief, investigations into fear and desire, the relationship between thinker and thought, the concept of choiceless awareness, the function of the mind, etc. Following an introductory chapter by Krishnamurti, each of twenty interrelated topics is covered in its own chapter. A second part ("Questions and Answers") consists of 38 named segments, taken from question-and-answer sessions between Krishnamurti and his audience; the segments broadly pertain to the topics covered in the book's first part. The book was edited (without attribution) by D. Rajagopal, Krishnamurti's then–close associate, editor, and business manager; the included extracts were taken from "Verbatim Reports" of Krishnamurti talks between 1947 and 1952.[8]

Huxley provided a ten-page foreword as comprehensive introduction to Krishnamurti's philosophy, an essay that "no doubt contributed to [the book's] credibility and sales potential",[9][10] and he may have also influenced the overall structure and style of the work. He had read a then–recent Krishnamurti book in 1941,[11] and was favorably impressed, especially with a section consisting of dialogues and question-and-answer sessions between Krishnamurti and his listeners – a practice that normally followed his lectures.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Huxley thought they enlivened Krishnamurti's philosophical subjects, and suggested a similar format for the forthcoming book, which also became a common type of presentation in later Krishnamurti publications.[12]

A commentator summarized that in this and other books, "Krishnamurti emphasized the importance of release from entrapment in the 'network of thought' through a perceptual process of attention, observation or 'choiceless awareness' which would release the true perception of reality without mediation of any authority, or guru."[13] Another observed that it was instrumental in making Krishnamurti and his ideas known to a wider audience, as the "first substantial statement of his philosophy to be issued by major publishing houses in Britain and the United States"; [14] noting the work's popularity among the college-age young, others added that the book "anticipated the preoccupations of an up-and-coming youth culture, and ... perhaps helped to form it".[15]

As in practically every work of his,[16] Krishnamurti did not present this book as containing "a doctrine to be believed, but as an invitation to others to investigate and validate its truth for themselves": [17]

Our problem is how to be free from all conditioning. Either you say it is impossible, that no human mind can ever be free from conditioning, or you begin to experiment, to inquire, to discover. ... Now I say it is definitely possible for the mind to be free from all conditioning – not that you should accept my authority. If you accept it on authority, you will never discover, ... and that will have no significance. ... [I]f you are to find the truth of it for yourself, you must experiment with it and follow it swiftly.

Publication history

The book was originally published May 1954 by Harper in the US and by Gollancz in the UK.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) In the US, it was the second Krishnamurti-authored book to be published by a mainstream commercial publisher – unlike in other markets, where this would be the first such publication.[18] Copyright was held by Krishnamurti Writings (KWINC), the organization then responsible for promoting Krishnamurti's work worldwide; [19] publishing rights were transferred to new Krishnamurti-related organizations in the mid-1970s (the Krishnamurti foundations), and in early 21st century, to Krishnamurti Publications (K Publications), an entity with overall responsibility for publishing his works worldwide.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

The book was "an immediate success" and was in its 6th impression by the end of 1954; ({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) a 2015 reprint of a 1975 paperback edition was the edition's 51st print run.[20] Opening to good reviews, it proved to be a "compelling entry" into publishing, helping to establish Krishnamurti as a viable author in the commercial publishing arena.[21] Unlike the editions of the 1950s and 60s, later editions of the work (such as one listed below), included a variety of Krishnamurti photographs on the front cover. A digital edition in several e-book formats was first published by HarperCollins e-Books in 2010 .

About a third of the work was included in The Penguin Krishnamurti Reader, a 1970 compilation edited by Krishnamurti biographer Mary Lutyens, that was also a commercial and critical success.[22] In addition, Penguin Books through its Ebury Publishing division published a new edition of The First and Last Freedom in 2013, with an edition-specific Preface. This was marketed as a mass market paperback by the division's Rider imprint , and as an e-book by its digital media imprint.[23]

As of 2022, according to one source, there had been 95 editions in several formats by a variety of publishers, published in eight languages.[24] Several years prior, the work had also been made available as a freely readable electronic document through J. Krishnamurti Online (JKO), the official Jiddu Krishnamurti online repository.[25]

Select editions

- Jiddu, Krishnamurti (May 1954). The first and last freedom (hardcover). Foreword by Huxley, Aldous (1st UK ed.). London: Gollancz. pp. 288 pp. OCLC 59002436. https://archive.org/details/dli.ernet.505958.

Reception

A Krishnamurti biographer wrote that Huxley's foreword "set the mood to take the work very seriously", and another stated that by the end of May 1954 the book was responsible for attracting larger audiences to Krishnamurti's talks.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Jean Burden, in a sympathetic 1959 article in the Prairie Schooner, partly attributed the increased interest in Krishnamurti to the book, while stating that as it was compiled from his "famous talks", it "suffered, as most compilations do, from repetitiveness and lack of structure."[26] Yet Anne Morrow Lindbergh reputedly found "'the sheer simplicity of what he [Krishnamurti] has to say ... breathtaking'."[27]

Kirkus Reviews described it as a "clear and intriguing presentation of a point of view which will appeal to many who are finding the more traditional approaches to truth to be blind alleys."[28] A review at The Atlanta Journal and the Atlanta Constitution contended that Krishnamurti's thinking "has the practical ring. It is so clear, so straightforward that the reader feels a challenge in every page".[29] In contrast, The Times of India, while finding the work's basic message unoriginal, maintained that Krishnamurti's utterances have "a fluid ambiguity and an almost insidious plausibility", before concluding that the work is "all theoria without praxis, and in the present context appears to be mere escapism."[30]

The Times Literary Supplement stated that for those who regard conflict "as an unchangeable condition of human life and truth, Krishnamurti's teaching will seem to offer a delusive short-cut to a vaguely beatific freedom. But there is nothing vague about it. It is precise and penetrating." The reviewer thinks that Krishnamurti presents "a reinterpretation of the wisdom of his race ... though he has rediscovered it for himself."[31] Nevertheless, J. M. Cohen reviewing the book for The Observer (London) wrote, "Krishnamurti is an entirely independent master" adding, "[f]or those who wish to listen, this book will have a value beyond words."[32]

The book's publication brought Krishnamurti and his ideas to the attention of practicing and theoretical psychotherapists, setting the stage for later dialogue between Krishnamurti and professionals in this field.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) It was also responsible for Krishnamurti's long and fruitful relationship with theoretical physicist David Bohm, whose unorthodox approach to problems of physics and of consciousness often correlated with Krishnamurti's philosophical views.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

The work was mentioned in education-related dissertations as early as August 1954; [33] it continued to be cited by educational researchers in the following decades.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) It has also interested researchers in psycholinguistics, drawing favorable remarks about Krishnamurti's views regarding the "separation ... between the thinker and the thought"; [34] and has featured in discussion of the relationship between general semantics and other viewpoints.[35]

Among other fields, the book has been cited by occupational therapy papers,[36] articles on medical ethics,[37] and in original research of contemporary spirituality.[38] But also in essays "on the social implications of the 'death of utopia'",[39] and in addresses to professional geography conferences.[40] It has been quoted in influential works on media[41] and has been commended as an aid to successful investment strategies.[42] Meanwhile, more than half a century after original publication, articles in general-interest media – for example, articles on meditation and mindfulness, favorably featured or mentioned the book.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

The book has inspired artistic endeavors: it has been suggested that it influenced Huxley's writing of the 1962 novel Island,[43] and a painting exhibition staged in London in 2014 was "derived from two alternative perspectives: the introduction by Aldous Huxley in the book of his long-term colleague and friend, Jiddu Krishnamurti and Krishnamurti's second major opus, The First and Last Freedom".({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Additionally, the book has prompted comparisons between Krishnamurti's philosophy and Emily Dickinson's poetry,[44] and has informed the way art therapy professionals approach their work.[45]

As of c. 2021, according to one of several official Krishnamurti-related foundations, The First and Last Freedom had "sold more copies than any other Krishnamurti book."[46]

See also

- Jiddu Krishnamurti bibliography

Notes

- ↑ Vernon 2001, ch. "10: Farewell to Things Past" pp. 187–212.

- ↑ Vernon 2001, p. 209.

- ↑ Lutyens 2003, pp. 45–46.

- ↑ Lutyens 2003, p. 59.

- ↑ Rajagopal Sloss 2011, p. 252. Retrieved 2016-03-25 – via Google Books (limited preview). Radha Rajagopal Sloss, daughter of D. Rajagopal, Krishnamurti's business manager at the time, states that Huxley introduced her father to the publisher. She adds that Krishnamurti had little interest in his manuscripts or other records of his work; this lack of interest by Krishnamurti is also remarked upon by his biographers (Lutyens 2003).

- ↑ Vernon 2001, pp. 199, 224–225.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Weeraperuma 1974, pp. 3–53, 1998, pp. 1–30. [In both titles the pages comprise "Part One: Works by Krishnamurti"].

- ↑ FoBP c. 2013, ¶¶ 2, 5, 7 [not numbered]. Extracts from "Verbatim Reports" of talks in Bombay (Mumbai ), Ojai, California, Madras (Chennai), New York City, Banaras (Varanasi), Bangalore, London, Rajahmundry, New Delhi, Poona (Pune) and Paris.

- ↑ Vernon 2001, p. 207. In the Foreword, Huxley, who previously disagreed with Krishnamurti's views on the worth of the intellect, "appears now to endorse [them]".

- ↑ Huxley 1954.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Williams 2004, pp. 260–261. According to a detailed Krishnamurti bibliography, almost all known texts of his from that period were full or partial transcripts of his talks and discussions, published in a variety of print media.[7]

- ↑ Williams 2004, p. 316. Krishnamurti and D. Rajagopal agreed with Huxley that "the immediacy of specific questions and answers about conduct in particular circumstances was a successful way to convey philosophical truths".

- ↑ Vas 2004, p. 4.

- ↑ Holroyd 1991, p. 28.

- ↑ Vernon 2001, p. 234.

- ↑ Vernon 2001, pp. 215, 231, 248.

- ↑ Rodrigues 1996, pp. 46, 54n20.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 In the US, Harper had published Education and the Significance of Life by Krishnamurti in 1953 (OCLC 177139); however, this title was published after The First and Last Freedom in the UK and elsewhere (Lutyens 2003, p. 86; Williams 2004, p. 308).

- ↑ Williams 2004, p. 266. Elsewhere, Williams states that according to Krishnamurti associate Ingram Smith, D. Rajagopal, as the head of KWINC, had offered to buy back from Gollancz any unsold inventory of the book's first edition.[11][18]

- ↑ J. Krishnamurti 1975, edition notice, printer's key line (2015 reprint).

- ↑ Williams 2004, p. 316.

- ↑ The Penguin Krishnamurti Reader (1970, vol. 1, 1st ed., ISBN 978-01-4003071-6, OCLC 120824); Lutyens 2003, p. 162; Williams 2004, p. 386.

- ↑ Penguin UK, "The First and Last Freedom". Retrieved 2021-11-03.

- ↑ WorldCat 2022. One licensee was the publishing arm of the Theosophical Society in America, whose parent organization had sponsored the World Teacher Project. See The First and Last Freedom at Google Books (1968 Theosophical Publishing ed., OCLC 218764); despite Krishnamurti's disassociation from Theosophy more than eight decades earlier, Theosophical organizations were scheduling events based on the book as of 2015 (Adelaide Theosophical Society 2016).

- ↑ Snapshots of the JKO document's pages were archived from a "legacy" version of the official repository in July 2011 . However, as of December 2022, the work was not available at the contemporary version of the repository.[update]

- ↑ Burden 1959, p. 271.

- ↑ Lutyens 2003, p. 87. Lindbergh quote regarding the book's 1st US edition.

- ↑ Bulletin 1954, positive brief review of the 1st US edition.

- ↑ Le Bey 1954, positive review of the 1st US edition.

- ↑ The Times of India 1954, negative review of the 1st UK edition. Huxley's endorsement of Krishnamurti's ideas is also criticized in this review.

- ↑ Fausset 1954, positive review of the 1st UK edition.

- ↑ Cohen 1954, positive review of the 1st UK edition.

- ↑ Ely 1954, p. 228. § "Recommended Background Reading" [in Bibliography].

- ↑ Middelman 1988, p. 274. "The understanding of this situation is more clearly expressed by Krishnamurti."

- ↑ Gorman 1978, pp. 164, 165–166.

- ↑ Kang 2003, p. 98.

- ↑ Pijnenburg & Leget 2007, p. 586.

- ↑ Schreiber 2012, §§ "The deconstruction of historicised ego", "The affirmative phenomenology of meta-consciousness, false-self and true-self".

- ↑ Bharucha 2000.

- ↑ Kennedy 2001, p. 14.

- ↑ Youngblood 2020, pp. 52, 61, 62. Quotes Krishnamurti on the futility of political revolutions, the limitations of memory, and the adverse effects of imitation.

- ↑ Plummer 2010, p. 392n10. "One of the clearest analyses of the beneficial effects of self-observation".

- ↑ Meckier 2011, pp. 327–329.

- ↑ Mahajan 2007.

- ↑ Lavery 1994, § "Conclusion".

- ↑ See § "Product Description" in archived snapshot from the Krishnamurti Foundation Trust Online Shop website: .

References

- Berry, William (2 February 2015). "You Might Be Better Off Not Reading This". Psychology Today (New York: Sussex Publishers). ISSN 0033-3107. https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-second-noble-truth/201502/you-might-be-better-not-reading. Retrieved 2016-04-14.

- Bharucha, Rustom (25 March 2000). "Enigmas of Time". Economic and Political Weekly (Mumbai: Sameeksha Trust) 35 (13): 1094–1100. ISSN 0012-9976. http://www.epw.in/journal/2000/13/special-articles/enigmas-time.html.

- Burden, Jean (Fall 1959). "Krishnamurti and the pathless land". Prairie Schooner (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press) 33 (3): 271–281. ISSN 0032-6682none (JSTOR access may require registration).

- Cohen, J. M. (John Michael) (16 May 1954). "The Simple Question". The Observer (London: Waldorf Astor): p. 11. ProQuest 475235566. ISSN 0029-7712.

- Ely, Jewel Mary (August 1954). The needs, interests, and problems of elementary age children (Master of Science in Education thesis). Los Angeles, California: University of Southern California. doi:10.25549/usctheses-c24-129196. Dissertation no. EP47862.

- "Exhibitions". Art Monthly (London: Britannia Art Publications) (379): 43. September 2014. ISSN 0142-6702. http://www.exacteditions.com/browsePages.do?issue=40006&size=2&pageLabel=43. Retrieved 2016-04-09.

- Fausset, Hugh l'Anson (14 May 1954). "Bond and Free". The Times Literary Supplement (London: TLS Education): 317. Gale EX1200099611. ISSN 0040-7895.

- Gorman, Michael E. (June 1978). "A. J. Korzybski, J. Krishnamurti, and Carlos Castaneda: A Modest Comparison". ETC: A Review of General Semantics (New York: Institute of General Semantics) 35 (2): 162–174. ISSN 0014-164Xnone (JSTOR access may require registration).

- Heshusius, Lous (April 1994). "Freeing Ourselves from Objectivity: Managing Subjectivity or Turning toward a Participatory Mode of Consciousness?". Educational Researcher (Washington, D.C.: American Educational Research Association) 23 (3): 15–22. doi:10.3102/0013189X023003015.

- Hiley, Basil J. (November 1997). "David Joseph Bohm. 20 December 1917–27 October 1992". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society (London: Royal Society) 43: 106–131. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1997.0007none (JSTOR access may require registration).

- Holroyd, Stuart (1991). Krishnamurti: the man, the mystery & the message (paperback) (1st ed.). Shaftesbury, Dorset & Rockport, Massachusetts: Element Books. ISBN 978-1-852302-0-09. https://archive.org/details/krishnamurtimanm0000holr.

- "Foreword". The first and last freedom (hardcover) (1st US ed.). New York: Harper & Brothers. 19 May 1954. pp. 9–18. JKO legacy document no. 306. OCLC 964457. http://legacy.jkrishnamurti.org/krishnamurti-teachings/view-text.php?tid=30&chid=385. Retrieved 2023-01-25.

- "K Publications". Ojai, California. n.d.. https://kfa.org/publishing/.

- Kang, Chris (June 2003). "A psychospiritual integration frame of reference for occupational therapy. Part 1: Conceptual foundations". Australian Occupational Therapy Journal (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing) 50 (2): 92–103. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1630.2003.00358.x.

- Kelman, Harold (January 1956). "Life history as therapy: Part II; On being aware". The American Journal of Psychoanalysis (New York: Association for the Advancement of Psychoanalysis) 16 (1): 68–78. doi:10.1007/bf01873714. ISSN 0002-9548.

- Kennedy, Tina (2001). "'I Too of the Wild Hills': Experience, Meaning, and Place". Yearbook of the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press) 63: 9–24. doi:10.1353/pcg.2001.0019. ISSN 0066-9628. "Presidential Address delivered to the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers, 63rd Annual Meeting, Areata, California, September 16, 2000"..

- Khattar, Randa (2010). "Brought-Forth Possibilities for Attentiveness in the Mathematics Classroom". Complicity (Alberta: University of Alberta) 7 (1): 57–62. doi:10.29173/cmplct8839. ISSN 1710-5668.

- "Krishnamurti". The Christian Century (Chicago, Illinois: Christian Century Foundation) 71 (25): 771. 23 June 1954. ISSN 0009-5281.

- "Krishnamurti, J. (Jiddu) 1895–1986". Dublin, Ohio: OCLC. 2022. § "Most widely held works by J. Krishnamurti". https://www.worldcat.org/wcidentities/lccn-n79-72898.

- "Krishnamurti's The First and Last Freedom: A History and Context". Bramdean: Krishnamurti Foundation Trust. c. 2013. http://friendsofbrockwoodpark.org.uk/first.html.

- Lavery, Terry P. (August 1994). "Culture shock: adventuring into the inner city through post-session imagery". American Journal of Art Therapy (Alexandria, Virginia: American Art Therapy Association): 14–20. EBSCOhost 9409130630. ISSN 0007-4764.

- Le Bey, Dave (30 May 1954). "Indian challenge to dark thinking". The Atlanta Journal and the Atlanta Constitution (Cox Enterprises): p. 5F. ProQuest 1635736527. ISSN 1539-7459.

- "List Of The Books Published Today". The New York Times: p. 29. 19 May 1954. ProQuest 112919786. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Lutyens, Mary (2003). Krishnamurti: the years of fulfillment (paperback) (1st KFT ed.). Bramdean: Krishnamurti Foundation Trust. ISBN 978-09-0050620-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=WKmJndX5B8wC. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- Mahajan, P. M. (July 2007). "Search For Self in Emily Dickinson's Poetry through J. Krishnamurti's Philosophy". PoetCrit (Maranda, India: Kanta Sahitya Prakashan) 20 (2): 16–20. ISSN 0970-2830.

- Maheshwari, Suresh C. (6 December 2005). "Meditation as a Complete Emptying of Mind". The Times of India (Mumbai: Bennett, Coleman & Co): p. 30. ProQuest 1516377721. OCLC 23379369.

- Meckier, Jerome (2011). Aldous Huxley, from Poet to Mystic (e-book). Human potentialities. 11. Berlin: LIT Verlag. ISBN 978-3-643-90101-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=d27Xt-gW-ZsC. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- Middelman, Francina (July 1988). "The Word and Us: Implications of Linguistic Design for Subjective Experience and for the Experience of Subjectivity". Journal of Psycholinguistic Research (New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers) 17 (4): 261–279. doi:10.1007/BF01067197.

- Pijnenburg, Martien A. M.; Leget, Carlo (October 2007). "Who Wants to Live Forever? Three Arguments against Extending the Human Lifespan". Journal of Medical Ethics (London: BMJ Group) 33 (10): 585–587. doi:10.1136/jme.2006.017822. PMID 17906056.

- Plummer, Tony (2010). Forecasting financial markets: the psychology of successful investing (e-book) (6th ed.). London & Philadelphia: Kogan Page. ISBN 978-07-494-5872-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=2ykC2vWg0gwC. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- Rajagopal Sloss, Radha (2011). Lives in the shadow with J. Krishnamurti (e-book). Lincoln, Nebraska: iUniverse. ISBN 978-14-6203131-3.

- Rodrigues, Hillary (January 1996). "J. Krishnamurti's 'religious mind'". Religious Studies and Theology (Sheffield, UK: Equinox Publishing) 15 (1): 40–55. ISSN 0829-2922.

- Schreiber, Dudley A. (17 February 2012). "On the epistemology of postmodern spirituality". Verbum et Ecclesia (Cape Town: AOSIS Publishing) 33 (1). doi:10.4102/ve.v33i1.398.

- "The First and Last Freedom". Bulletin (New York: Kirkus' Bookshop Service) 22 (11): 352. 1 June 1954. ISSN 1948-7428. https://www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/j-krishnamurti/the-first-and-last-freedom/. Retrieved 2022-04-02.

- "The First and Last Freedom" (Press release). London: MOT International. 2014. Archived from the original on 2015-01-16. Retrieved 2022-03-22 – via Wayback Machine.

- "The First and Last Freedom by Krishnamurthi". The Times of India (Mumbai: Bennett, Coleman & Co): p. 6. 22 August 1954. ProQuest 739974217. OCLC 23379369. "[Variant spelling:] Krishnamurthi".

- "Upcoming Events The First and Last Freedom". 2016. http://theosophical.org.au/event/the-first-and-last-freedom-8/. "Date: October 2, 2015".

- Vas, Luis S. R. (2004). J. Krishnamurti: great liberator or failed messiah? (paperback) (1st Indian ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-2051-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=9-fzHE8pRlUC. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- Vernon, Roland (2001). Star in the east: Krishnamurti: the invention of a messiah (hardcover). New York: Palgrave. ISBN 978-0-312-23825-4. https://archive.org/details/starineastkrishn00vern.

- Weeraperuma, Susunaga (1974). A bibliography of the life and teachings of Jiddu Krishnamurti (hardcover) (1st ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-04007-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=GeIUAAAAIAAJ. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- Williams, Christine V. (2004). Jiddu Krishnamurti: world philosopher (1895–1986): his life and thoughts (hardcover) (1st ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-2032-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=NzDar6XfICEC. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- Youngblood, Gene (2020). Expanded cinema: Fiftieth anniversary edition (paperback). Meaning Systems. Introduction by Fuller, R. Buckminster (1st ed.). New York: Fordham University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctvnwbz7q. ISBN 978-0823287413.

|

KSF

KSF