Wild animal suffering

Topic: Philosophy

From HandWiki - Reading time: 65 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 65 min

| Part of a series on |

| Animal rights |

|---|

|

Ideas |

|

Related |

Wild animal suffering is the suffering experienced by nonhuman animals living outside of direct human control, due to harms such as disease, injury, parasitism, starvation and malnutrition, dehydration, weather conditions, natural disasters, and killings by other animals,[1][2] as well as psychological stress.[3] Some estimates indicate that the vast majority of individual animals in existence live in the wild.[4] A vast amount of natural suffering has been described as an unavoidable consequence of Darwinian evolution[5] and the pervasiveness of reproductive strategies which favor producing large numbers of offspring, with a low amount of parental care and of which only a small number survive to adulthood, the rest dying in painful ways, has led some to argue that suffering dominates happiness in nature.[1][6][7]

The topic has historically been discussed in the context of the philosophy of religion as an instance of the problem of evil.[8] More recently, starting in the 19th-century, a number of writers have considered the suspected scope of the problem from a secular standpoint as a general moral issue, one that humans might be able to take actions toward preventing.[9] There is considerable disagreement around this latter point as many believe that human interventions in nature, for this reason, should not take place because of practicality,[10] valuing ecological preservation over the well-being and interests of individual animals,[11] considering any obligation to reduce wild animal suffering implied by animal rights to be absurd,[12] or viewing nature as an idyllic place where happiness is widespread.[6] Some have argued that such interventions would be an example of human hubris, or playing God and use examples of how human interventions, for other reasons, have unintentionally caused harm.[13] Others, including animal rights writers, have defended variants of a laissez-faire position, which argues that humans should not harm wild animals, but that humans should not intervene to reduce natural harms that they experience.[14][15]

Advocates of such interventions argue that animal rights and welfare positions imply an obligation to help animals suffering in the wild due to natural processes. Some have asserted that refusing to help animals in situations where humans would consider it wrong not to help humans is an example of speciesism.[2] Others argue that humans intervene in nature constantly—sometimes in very substantial ways—for their own interests and to further environmentalist goals.[16] Human responsibility for enhancing existing natural harms has also been cited as a reason for intervention.[17] Some advocates argue that humans already successfully help animals in the wild, such as vaccinating and healing injured and sick animals, rescuing animals in fires and other natural disasters, feeding hungry animals, providing thirsty animals with water, and caring for orphaned animals.[18] They also assert that although wide-scale interventions may not be possible with our current level of understanding, they could become feasible in the future with improved knowledge and technologies.[19][20] For these reasons, they claim it is important to raise awareness about the issue of wild animal suffering, spread the idea that humans should help animals suffering in these situations and encourage research into effective measures which can be taken in the future to reduce the suffering of these individuals, without causing greater harms.[6][16]

Extent of suffering in nature

Sources of harm

Disease

Animals in the wild may suffer from diseases which circulate similarly to human colds and flus, as well as epizootics, which are analogous to human epidemics; epizootics are relatively understudied in the scientific literature.[21] Some well-studied examples include chronic wasting disease in elk and deer, white-nose syndrome in bats, devil facial tumour disease in Tasmanian devils and Newcastle disease in birds.[21] Examples of other diseases include myxomatosis and viral haemorrhagic disease in rabbits,[22] ringworm and cutaneous fibroma in deer,[23] and chytridiomycosis in amphibians.[24] Diseases, combined with parasitism, "may induce listlessness, shivering, ulcers, pneumonia, starvation, violent behavior, or other gruesome symptoms over the course of days or weeks leading up to death."[1]

Poor health may dispose wild animals to increased risk of infection, which in turn reduces the health of the animal, further increasing the risk of infection.[25] The terminal investment hypothesis holds that infection can lead some animals to focus their limited remaining resources on increasing the number of offspring they produce.[26]

Injury

Wild animals can experience injury from a variety of causes such as predation; intraspecific competition; accidents, which can cause fractures, crushing injuries, eye injuries and wing tears; self-amputation; molting, a common source of injury for arthropods; extreme weather conditions, such as storms, extreme heat or cold weather; and natural disasters. Such injuries may be extremely painful, which can lead to behaviors which further negatively affect the well-being of the injured animal. Injuries can also make animals susceptible to diseases and other injuries, as well as parasitic infections. Additionally, the affected animal may find it harder to eat and drink and struggle to escape from predators and attacks from other members of their species.[27]

Parasitism

Many wild animals, particularly larger ones, have been found to be infected with at least one parasite. Parasites can negatively affect the well-being of their hosts by redirecting their host's resources to themselves, destroying their host's tissue and increasing their host's susceptibility to predation.[21] As a result, parasites may reduce the movement, reproduction and survival of their hosts.[28] Parasites can alter the phenotype of their hosts; limb malformations in amphibians caused by ribeiroia ondatrae, is one example.[29] Some parasites have the capacity to manipulate the cognitive function of their hosts, such as worms which make crickets kill themselves by directing them to drown themselves in water, so that the parasite can reproduce in an aquatic environment, as well as caterpillars using dopamine containing secretions to manipulating ants to acts as bodyguards to protect the caterpillar from parasites.[30] It is rare that parasites directly cause the death of their host, rather, they may increase the chances of their host's death by other means;[21] one meta-study found that mortality was 2.65 times higher in animals affected by parasites, than those that weren't.[31]

Unlike parasites, parasitoids—which include species of worms, wasps, beetles and flies—kill their hosts, who are generally other invertebrates.[32] Parasitoids specialize in attacking one particular species. Different methods are used by parasitoids to infect their hosts: laying their eggs on plants which are frequently visited by their host, laying their eggs on or close to the host's eggs or young and stinging adult hosts so that they are paralyzed, then laying their eggs near or on them.[32] The larvae of parasitoids grow by feeding on the internal organs and bodily fluids of their hosts,[33] which eventually leads to the death of their host when their organs have ceased to function, or they have lost all of their bodily fluids.[32] Superparasitism is a phenomenon where multiple different parasitoid species simultaneously infect the same host.[34] Parasitoid wasps have been described as having the largest number of species of any other animal species.[35]

Starvation and malnutrition

Starvation and malnutrition particularly affect young, old, sick and weak animals, and can be caused by injury, disease, poor teeth and environmental conditions, with winter being particularly associated with an increased risk.[36] It is argued that because food availability limits the size of wild animal populations, that this means that a huge number of individuals die as a result of starvation; such deaths are described as prolonged and marked by extreme distress as the animal's bodily functions shut down.[37]: 67 Within days of hatching, fish larvae may experience hydrodynamic starvation, whereby the motion of fluids in their environment limits their ability to feed; this can lead to mortality of greater than 99%.[38]

Dehydration

Dehydration is associated with high mortality in wild animals. Drought can cause many animals in larger populations to die of thirst. Thirst can also expose animals to an increased risk of being preyed upon; they may remain hidden in safe spaces to avoid this. However, their need for water may eventually force them to leave these spaces; being in a weakened state, this makes them easier targets for predatory animals. Animals who remain hidden cannot move due to dehydration and may end up dying of thirst. When dehydration is combined with starvation, the process of dehydration can be accelerated.[39] Diseases, such as chytridiomycosis, can also increase the risk of dehydration.[40]

Weather conditions

Weather has a strong influence on the health and survival of wild animals. Weather phenomena such as heavy snow, flooding and droughts can directly harm animals.[41] and indirectly harm them by increasing the risks of other forms of suffering, such as starvation and disease.[41] Extreme weather can cause the deaths of animals by destroying their habitats and directly killing animals;[42] hailstorms are known to kill thousands of birds.[43][44] Certain weather conditions may maintain large numbers of individuals over many generations; such conditions, while conducive to survival, may still cause suffering for animals. Humidity or lack thereof can be beneficial or harmful depending on an individual animals' needs.[41]

Deaths of large numbers of animals—particularly cold-blooded ones such as amphibians, reptiles, fishes and invertebrates—can take place as a result of temperature fluctuations, with young animals being particularly susceptible. Temperature may not be a problem for parts of the year, but can be a problem in especially hot summers or cold winters.[41] Extreme heat and lack of rainfall are also associated with suffering and increased mortality by increasing susceptibility to disease and causing vegetation that insects and other animals rely upon to dry out; this drying out can also make animals who rely on plants as hiding places more susceptible to predation. Amphibians who rely on moisture to breathe and stay cool may die when water sources dry up.[45] Hot temperatures can cause fish to die by making it hard for them to breathe.[46] Climate change and associated warming and drying is making certain habitats intolerable for some animals through heat stress and reducing available water sources.[47] Mass mortality is particularly linked with winter weather due to low temperatures, lack of food and bodies of water where animals live, such as frogs, freezing over;[48] a study on cottontail rabbits indicates that only 32% of them survive the winter.[49] Fluctuating environmental conditions in the winter months is also associated with increased mortality.[50]

Natural disasters

Fires, volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, tsunamis, hurricanes, storms, floods and other natural disasters are sources of extensive short- and long-term harm for wild animals, causing death, injury, illness and malnutrition, as well as poisoning by contaminating food and water sources.[51] Such disasters can also alter the physical environment of individual animals in ways which are harmful to them;[52] fires and large volcanic eruptions can affect the weather and marine animals may die due to disasters affecting water temperature and salinity.[51]

Killing by other animals

Predation has been described as the act of one animal capturing and killing another animal to consume part or all of their body.[53] Jeff McMahan, a moral philosopher, asserts that: "Wherever there is animal life, predators are stalking, chasing, capturing, killing, and devouring their prey. Agonized suffering and violent death are ubiquitous and continuous."[54] Preyed upon animals die in a variety of different ways, with the time taking for them to die, which can be lengthy, depending on the method that the predatory animal uses to kill them; some animals are swallowed and digested while still being alive.[55] Other preyed upon animals are paralysed with venom before being eaten; venom can also be used to start digesting the animal.[56]

Animals may be killed by members of their own species due to territorial disputes, competition for mates and social status, as well as cannibalism, infanticide and siblicide.[57]

Psychological stress

It has been argued that animals in the wild do not appear to be happier than domestic animals, based on findings that these individuals have greater levels of cortisol and elevated stress responses relative to domestic animals; additionally, unlike domestic animals, wild animals do not have their needs provided for them by human caretakers.[3] Sources of stress for these individuals include illness and infection, predation avoidance, nutritional stress and social interactions; these stressors can begin before birth and continue as the individual develops.[58]

A framework known as the ecology of fear conceptualises the psychological impact that the fear of predatory animals can have on the individuals that they predate, such as altering their behavior and reducing their survival chances.[59][60] Fear-inducing interactions with predators may cause lasting effects on behavior and PTSD-like changes in the brains of animals in the wild.[61] These interactions can also cause a spike in stress hormones, such as cortisol, which can increase the risk of both the individual's death and their offspring.[62]

Number of affected individuals

The number of individual animals in the wild is relatively unexplored in the scientific literature and estimates vary considerably.[63] An analysis, undertaken in 2018, estimates (not including wild mammals) that there are 1015 fish, 1011 wild birds, 1018 terrestrial arthropods and 1020 marine arthropods, 1018 annelids, 1018 molluscs and 1016 cnidarians, for a total of 1021 wild animals.[64] It has been estimated that there are 2.25 times more wild mammals than wild birds in Britain, but the authors of this estimate assert that this calculation would likely be a severe underestimate when applied to the number of individual wild mammals in other continents.[65]

Based on some of these estimates, it has been argued that the number of individual wild animals in existence is considerably higher, by an order of magnitude, than the number of animals humans kill for food each year,[4] with individuals in the wild making up over 99% of all sentient beings in existence.[66]

Natural selection

In his autobiography, the naturalist and biologist Charles Darwin acknowledged that the existence of extensive suffering in nature was fully compatible with the workings of natural selection, yet maintained that pleasure was the main driver of fitness-increasing behavior in organisms.[67] Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins challenged Darwin's claim in his book River Out of Eden, wherein he argued that wild animal suffering must be extensive due to the interplay of the following evolutionary mechanisms:

- Selfish genes – genes are wholly indifferent to the well-being of individual organisms as long as DNA is passed on.

- The struggle for existence – competition over limited resources results in the majority of organisms dying before passing on their genes.

- Malthusian checks – even bountiful periods within a given ecosystem eventually lead to overpopulation and subsequent population crashes.

From this, Dawkins concludes that the natural world must necessarily contain enormous amounts of animal suffering as an inevitable consequence of Darwinian evolution.[5] To illustrate this he writes:

The total amount of suffering per year in the natural world is beyond all decent contemplation. During the minute that it takes me to compose this sentence, thousands of animals are being eaten alive, many others are running for their lives, whimpering with fear, others are slowly being devoured from within by rasping parasites, thousands of all kinds are dying of starvation, thirst, and disease. It must be so. If there ever is a time of plenty, this very fact will automatically lead to an increase in the population until the natural state of starvation and misery is restored.[68]

Reproductive strategies and population dynamics

Some writers have argued that the prevalence of r-selected animals in the wild—who produce large numbers of offspring, with a low amount of parental care, and of which only a small number, in a stable population, will survive to adulthood—indicates that the average life of these individuals is likely to be very short and end in a painful death.[6][7] The pathologist Keith Simpson described this as follows:

In the wild, plagues of excess population are a rarity. The seas are not crowded with sunfish; the ponds are not brimming with toads; elephants do not stand shoulder to shoulder over the land. With few exceptions, animal populations are remarkably stable. On average, of each pair's offspring, only sufficient survive to replace the parents when they die. Surplus young die, and birth rates are balanced by death rates. In the case of spawners and egg layers, some young are killed before hatching. Almost half of all blackbird eggs are taken by jays, but even so, each pair usually manages to fledge about four young. By the end of summer, however, an average of under two are still alive. Since one parent will probably die or be killed during the winter, only one of the young will survive to breed the following summer. The high mortality rate among young animals is an inevitable consequence of high fecundity. Of the millions of fry produced by a pair of sunfish, only one or two escape starvation, disease or predators. Half the young of house mice living on the Welsh island of Skokholm are lost before weaning. Even in large mammals, the lives of the young can be pathetically brief and the killing wholesale. During the calving season, many young wildebeeste, still wet, feeble and bewildered, are seized and torn apart by jackals, hyenas and lions within minutes of emerging from their mothers' bellies. Three out of every four die violently within six months.[69]

According to this view, the lives of the majority of animals in the wild likely contain more suffering than happiness, since a painful death would outweigh any short-lived moments of happiness experienced in their short lives.[6][70][71]

Welfare economist Yew-Kwang Ng has argued that evolutionary dynamics can lead to welfare outcomes that are worse than necessary for a given population equilibrium.[70] A 2019 follow-up challenged the conclusions of Ng's original paper.[72]

History of concern for wild animals

Religious views

Problem of evil

The idea that suffering is common in nature has been observed by several writers historically who engaged with the problem of evil. In his notebooks (written between 1487 and 1505), Italian polymath Leonardo da Vinci described the suffering experienced by animals in the wild due to predation and reproduction, questioning: "Why did nature not ordain that one animal should not live by the death of another?"[73] In his 1779 posthumous work Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, the philosopher David Hume described the antagonism inflicted by animals upon each other and the psychological impact experienced by the victims, observing: "The stronger prey upon the weaker, and keep them in perpetual terror and anxiety."[74]

In Natural Theology, published in 1802, Christian philosopher William Paley argued that animals in the wild die as a result of violence, decay, disease, starvation and malnutrition, and that they exist in a state of suffering and misery; their suffering unaided by their fellow animals. He compared this to humans, who even when they can't relieve the suffering of their fellow humans, at least provide them with necessities. Paley also engaged with the reader of his book, asking whether, based on these observations, "you would alter the present system of pursuit and prey?"[75]: 261–262 Additionally, he argued that "the subject ... of animals devouring one another, forms the chief, if not the only instance, in the works of the Deity ... in which the character of utility can be called in question."[75]: 265 However, he defended predation as being a part of God's design by asserting that it was a solution to the problem of superfecundity;[76] animals producing more offspring than can possibly survive.[75]: 264 Paley also contended that venom is a merciful way for poisonous animals to kill the animals that they predate.[76]

The problem of evil has also been extended to include the suffering of animals in the context of evolution.[77][78] In Phytologia, or the Philosophy of Agriculture and Gardening, published in 1800, Erasmus Darwin, a physician and the grandfather of Charles Darwin, aimed to vindicate the goodness of God allowing the consumption of "lower" animals by "higher" ones, by asserting that "more pleasurable sensation exists in the world, as the organic matter is taken from a state of less irritability and less sensibility and converted into a greater"; he claimed that this process secures the greatest happiness for sentient beings. Writing in response, in 1894, Edward Payson Evans, a linguist and advocate for animal rights, argued that evolution, which regards the antagonism between animals purely as events within the context of a "universal struggle for existence", has disregarded this kind of theodicy and ended "teleological attempts to infer from the nature and operations of creation the moral character of the Creator".[79]

In an 1856 letter to Joseph Dalton Hooker, Charles Darwin remarked sarcastically on the cruelty and wastefulness of nature, describing it as something that a "Devil's chaplain" could write about.[80] Writing in 1860, to Asa Gray, Darwin asserted that he could not reconcile an omnibenevolent and omnipotent God with the intentional existence of the Ichneumonidae, a parasitoid wasp family, the larvae of which feed internally on the living bodies of caterpillars.[81] In his autobiography, published in 1887, Darwin described a feeling of revolt at the idea that God's benevolence is limited, stating: "for what advantage can there be in the sufferings of millions of the lower animals throughout almost endless time?"[82]

Eastern perspectives

Philosopher Ole Martin Moen argues that unlike Western, Judeo-Christian views, Jainism, Buddhism and Hinduism "all hold that the natural world is filled with suffering, that suffering is bad for all who endure it, and that our ultimate aim should be to bring suffering to an end."[83] In Buddhist doctrine, rebirth as an animal is regarded as evil because of the different forms of suffering that animals experience due to humans and natural processes.[84] Buddhists may also regard the suffering experienced by animals in nature as evidence for the truth of dukkha.[85] Patrul Rinpoche, a 19th-century Tibetan Buddhist teacher, described animals in the ocean as experiencing "immense suffering", as a result of predation, as well as parasites burrowing inside them and eating them alive. He also described animals on land as existing in a state of continuous fear and of killing and being killed.[86]

18th century

In Histoire Naturelle, published in 1753, the naturalist Buffon described wild animals as suffering much want in the winter, focusing specifically on the plight of stags who are exhausted by the rutting season, which in turn leads to the breeding of parasites under their skin, further adding to their misery.[87]: 53 Later in the book, he described predation as necessary to prevent the superabundance of animals who produce vast numbers of offspring, who if not killed would have their fecundity diminished due to a lack of food and would die as a result of disease and starvation. Buffon concluded that "violent deaths seem to be equally as necessary as natural ones; they are both modes of destruction and renovation; the one serves to preserve nature in a perpetual spring, and the other maintains the order of her productions, and limits the number of each species."[87]: 116–117

Herder, a philosopher and theologian, in Ideen zur Philosphie der Geschichte der Menschheit, published between 1784 and 1791, argued that animals exist in a state of constant striving, needing to provide for their own subsistence and to defend their lives. He contended that nature ensured peace in creation by creating an equilibrium of animals with different instincts and belonging to different species who live opposed to each other.[88]

19th century

In 1824, Lewis Gompertz, an early vegan and animal rights activist, published Moral Inquiries on the Situation of Man and of Brutes, in which he advocated for an egalitarian view towards animals and aiding animals suffering in the wild.[4] Gompertz asserted that humans and animals in their natural state both suffer similarly:

[B]oth of them being miserably subject to almost every evil, destitute of the means of palliating them; living in the continual apprehension of immediate starvation, of destruction by their enemies, which swarm around them; of receiving dreadful injuries from the revengeful and malicious feelings of their associates, uncontrolled by laws or by education, and acting as their strength alone dictates; without proper shelter from the inclemencies of the weather; without proper attention and medical or surgical aid in sickness; destitute frequently of fire, of candle-light, and (in man) also of clothing; without amusements or occupations, excepting a few, the chief of which are immediately necessary for their existence, and subject to all the ill consequences arising from the want of them.[89]: 47

Gompertz also argued that as much as animals suffer in the wild, that they suffer much more at the hands of humans because, in their natural state, they have the capacity to also experience periods of much enjoyment.[89]: 52 Additionally, he contended that if he was to encounter a situation where an animal was eating another, that he would intervene to help the animal being attacked, even if "this might probably be wrong."[89]: 93–94

Philosopher and poet Giacomo Leopardi in his 1824 "Dialogue between Nature and an Icelander", from Operette morali, used images of animal predation, which he rejected as having value, to represent nature's cycles of creation and destruction.[90] Writing in his notebooks, Zibaldone di pensieri, published posthumously in 1898, Leopardi asserted that predation is a leading example of the evil design of nature.[91]

In 1851, the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer commented on the vast amount of suffering in nature, drawing attention to the asymmetry between the pleasure experienced by a carnivorous animal and the suffering of the animal that they are consuming, stating: "Whoever wants summarily to test the assertion that the pleasure in the world outweighs the pain, or at any rate that the two balance each other, should compare the feelings of an animal that is devouring another with those of that other".[92]

In the 1874 posthumous essay "Nature", utilitarian philosopher John Stuart Mill wrote about suffering in nature and the imperative of struggling against it:

In sober truth, nearly all the things which men are hanged or imprisoned for doing to one another, are nature's every day performances. ... The phrases which ascribe perfection to the course of nature can only be considered as the exaggerations of poetic or devotional feeling, not intended to stand the test of a sober examination. No one, either religious or irreligious, believes that the hurtful agencies of nature, considered as a whole, promote good purposes, in any other way than by inciting human rational creatures to rise up and struggle against them. ... Whatsoever, in nature, gives indication of beneficent design proves this beneficence to be armed only with limited power; and the duty of man is to cooperate with the beneficent powers, not by imitating, but by perpetually striving to amend, the course of nature—and bringing that part of it over which we can exercise control more nearly into conformity with a high standard of justice and goodness.[93]

In his 1892 book Animals' Rights: Considered in Relation to Social Progress, the writer and early activist for animal rights Henry Stephens Salt focused an entire chapter on the plight of wild animals, "The Case of Wild Animals". Salt wrote that the rights of animals should not be dependent on the rights of being property and that sympathy and protection should be extended to non-owned animals too.[94] He also argued that humans are justified in killing wild animals in self-defense, but that neither unnecessary killing nor torturing harmless beings is justified.[94]

20th century

In the 1906 book The Universal Kinship, the zoologist and utilitarian philosopher J. Howard Moore argued that the egoism of sentient beings—a product of natural selection—which leads them to exploit their sentient fellows, was the "most mournful and immense fact in the phenomena of conscious life", and speculated whether an ordinary human who was sufficiently sympathetic to the welfare of the world could significantly improve this situation if only given the opportunity.[95] In Ethics and Education, published in 1912, Moore critiqued the human conception of animals in the wild: "Many of these non-human beings are so remote from human beings in language, appearance, interests, and ways of life, as to be nothing but 'wild animals.' These 'wild things' have, of course, no rights whatever in the eyes of men."[96]: 71 Later in the book, he described them as independent beings who suffer and enjoy in the same way humans do and have their "own ends and justifications of life."[96]: 157

In his 1952 article "Which Shall We Protect? Thoughts on the Ethics of the Treatment of Free Life", Alexander Skutch, a naturalist and writer, explored five ethical principles that humans could follow when considering their relationship with animals in the wild, including the principle of only considering human interests; the laissez-faire, or "hands-off" principle; the do no harm, ahmisa principle; the principle of favoring the "higher animals", which are most similar to ourselves; the principle of "harmonious association", whereby humans and animals in the wild could live symbiotically, with each providing benefits to the other and individuals who disrupt this harmony, such as predators, are removed. Skutch endorsed a combination of the laissez-faire, ahimsa and harmonious association approaches as the way to create the ultimate harmony between humans and animals in the wild.[97]

Moral philosopher Peter Singer, in 1973, responded to a question on whether humans have a moral obligation to prevent predation, arguing that intervening in this way may cause more suffering in the long-term, but asserting that he would support actions if the long-term outcome was positive.[98]

In 1979, the animal rights philosopher Stephen R. L. Clark, published "The Rights of Wild Things", in which he argued that humans should protect animals in the wild from particularly large dangers, but that humans do not have an obligation to regulate all of their relationships.[99] The following year, J. Baird Callicott, an environmental ethicist, published "Animal Liberation: A Triangular Affair", in which he compared the ethical underpinnings of the animal liberation movement, asserting that it is based on Benthamite principles, and Aldo Leopold's land ethic, which he used as a model for environmental ethics. Callicott concluded that intractable differences exist between the two ethical positions when it comes to the issue of wild animal suffering.[100]

In 1991, the environmental philosopher Arne Næss critiqued what he termed the "cult of nature" of contemporary and historical attitudes of indifference towards suffering in nature. He argued that humans should confront the reality of the wilderness, including disturbing natural processes—when feasible—to relieve suffering.[101]

In his 1993 article "Pourquoi je ne suis pas écologiste" ("Why I am not an environmentalist"), published in the antispeciesist journal Cahiers antispécistes, the animal rights philosopher David Olivier argued that he is opposed to environmentalists because they consider predation to be good because of the preservation of species and "natural balance", while Olivier gives consideration to the suffering of the individual animal being predated. He also asserted that if the environmentalists were themselves at risk of being predated, they wouldn't follow the "order of nature". Olivier concluded: "I don't want to turn the universe into a planned, man-made world. Synthetic food for foxes, contraception for hares, I only half like that. I have a problem that I do not know how to solve, and I am unlikely to find a solution, even theoretical, as long as I am (almost) alone looking for one."[102]

21st century

In 2009, essayist Brian Tomasik wrote an influential essay, "The Importance of Wild-Animal Suffering".[103] In 2015, a version of the essay was published in the journal Relations: Beyond Anthropocentrism.[1]

In 2010, philosopher Jeff McMahan's essay "The Meat Eaters" was published by The New York Times, in which he argued in favor of taking steps to reduce animal suffering in the wild, particularly by reducing predation.[104] In the same year, McMahan published "Predators: A Response", a reply to the criticism he received for his original article.[105]

In 2015, sociologist Jacy Reese Anthis published an article in Vox titled, "Wild animals endure illness, injury, and starvation. We should help."[106]

In 2016, philosopher Catia Faria successfully defended her Ph.D. thesis, Animal Ethics Goes Wild: The Problem of Wild Animal Suffering and Intervention in Nature, which argued that humans have an obligation to help animals in the wild.[107]

In 2020, philosopher Kyle Johannsen published Wild Animal Ethics: The Moral and Political Problem of Wild Animal Suffering. The book argues that wild animal suffering is a pressing moral issue and that humans have a collective moral duty to intervene in nature to reduce suffering.[108]

In response to these arguments for the moral and political importance of wild animal suffering, a number of organizations have been created to research and address the issue. Two of these, Utility Farm and Wild Animal Suffering Research, merged in 2019 to form Wild Animal Initiative.[109] The nonprofit organization Animal Ethics also researches wild animal suffering and advocates on behalf of wild animals, among other populations.[110]

Philosophical status

Predation as a moral problem

Predation has been considered a moral problem by some philosophers, who argue that humans have an obligation to prevent it,[12][111] while others argue that intervention is not ethically required.[112][113] Others have argued that humans shouldn't do anything about it right now because there's a chance we'll unwittingly cause serious harm, but that with better information and technology, it may be possible to take meaningful action in the future.[114] An obligation to prevent predation has been considered untenable or absurd by some writers, who have used the position as a reductio ad absurdum to reject the concept of animal rights altogether.[115][116] Others have argued that attempting to reduce it would be environmentally harmful.[117]

Arguments for intervention

Animal rights and welfare perspectives

Some theorists have reflected on whether the harms animals suffer in the wild should be accepted or if something should be done to mitigate them.[6] The moral basis for interventions aimed at reducing wild animal suffering can be rights or welfare based. Advocates of such interventions argue that non-intervention is inconsistent with either of these approaches.

From a rights-based perspective, if animals have a moral right to life or bodily integrity, intervention may be required to prevent such rights from being violated by other animals.[118] Animal rights philosopher Tom Regan was critical of this view; he argued that because animals aren't moral agents, in the sense of being morally responsible for their actions, they can't violate each other's rights. Based on this, he concluded that humans don't need to concern themselves with preventing suffering of this kind, unless such interactions were strongly influenced by humans.[119]: 14–15

The moral philosopher Oscar Horta argues that it is a mistaken perception that the animal rights position implies a respect for natural processes because of the assumption that animals in the wild live easy and happy lives, when in reality, they live short and painful lives full of suffering.[6] It has also been argued that a non-speciesist legal system would mean animals in the wild would be entitled to positive rights—similar to what humans are entitled to by their species-membership—which would give them the legal right to food, shelter, healthcare and protection.[120]

From a welfare-based perspective, a requirement to intervene may arise insofar as it is possible to prevent some of the suffering experienced by wild animals without causing even more suffering.[121] Katie McShane argues that biodiversity is not a good proxy for wild animal welfare: "A region with high biodiversity is full of lots of different kinds of individuals. They might be suffering; their lives might be barely worth living. But if they are alive, they count positively toward biodiversity."[122]

Non-intervention as a form of speciesism

Some writers have argued that humans refusing to aid animals suffering in the wild, when they would help humans suffering in a similar situation, is an example of speciesism;[2] the differential treatment or moral consideration of individuals based on their species membership.[123] Jamie Mayerfeld contends that a duty to relive suffering which is blind to species membership implies an obligation to relieve the suffering of animals due to natural processes.[124] Stijn Bruers argues that even long-term animal rights activists sometimes hold speciesist views when it comes to this specific topic, which he calls a "moral blind spot".[125] His view is echoed by Eze Paez, who asserts that advocates who disregard the interests of animals purely because they live in the wild are responsible for the same form of discrimination used by those who justify the exploitation of animals by humans.[126] Oscar Horta argues that spreading awareness of speciesism will in turn increase concern for the plight of animals in the wild.[127]

Humans already intervene to further human interests

Oscar Horta asserts that humans are constantly intervening in nature, in significant ways, to further human interests, such as furthering environmentalist ideals. He criticizes how interventions are considered to be realistic, safe or acceptable when their aims favor humans, but not when they focus on helping wild animals. He argues that humans should shift the aim of these interventions to consider the interests of sentient beings; not just humans.[16]

Human responsibility for enhancing natural harms

Philosopher Martha Nussbaum asserts that humans continually "affect the habitats of animals, determining opportunities for nutrition, free movement, and other aspects of flourishing" and contends that the pervasive human involvement in natural processes means that humans have a moral responsibility to help individuals affected by our actions. She also argues that humans may have the capacity to help animals suffering due to entirely natural processes, such as diseases and natural disasters and asserts that way may have duties to provide care in these cases.[128]: 374

Jeff Sebo, a philosopher, argues that animals in the wild suffer as a result of natural processes, as well as human-caused harms. He asserts that climate change is making existing harms more severe and creating new harms for these individuals. From this, he concludes that there are two reasons to help individual animals in the wild: "they are suffering and dying, and we are either partly or wholly responsible".[17] Similarly, philosopher Steven Nadler argues that climate change means "that the scope of actions that are proscribed – and, especially, prescribed – by a consideration of animal suffering should be broadened".[129] However, Nadler goes further, asserting that humans have a moral obligation to help individual animals suffering in the wild regardless of human responsibility.[129]

Arguments against intervention

Practicality of intervening in nature

A common objection to intervening in nature is that it would be impractical, either because of the amount of work involved or because the complexity of ecosystems would make it difficult to know whether or not an intervention would be net beneficial on balance.[105] Aaron Simmons argues that humans should not intervene to save animals in nature because doing so would result in unintended consequences such as damaging ecosystems, interfering with human projects, or resulting in more animal deaths overall.[12] Nicolas Delon and Duncan Purves argue that the "nature of ecosystems leaves us with no reason to predict that interventions would reduce, rather than exacerbate, suffering".[10] Peter Singer has argued that intervention in nature would be justified if one could be reasonably confident that this would greatly reduce wild animal suffering and death in the long run. In practice, however, Singer cautions against interfering with ecosystems because he fears that doing so would cause more harm than good.[98][130]

Other authors dispute Singer's empirical claim about the likely consequences of intervening in the natural world and argue that some types of intervention can be expected to produce good consequences overall. Economist Tyler Cowen cites examples of animal species whose extinction is not generally regarded as having been on balance bad for the world. Cowen also notes that insofar as humans are already intervening in nature, the relevant practical question is not whether there should be intervention, but what particular forms of intervention should be favored.[121] Oscar Horta similarly writes that there are already many cases in which humans intervene in nature for other reasons, such as for human interest in nature and environmental preservation as something valuable in their own rights.[6] Horta has also proposed that courses of action aiming at helping wild animals should be carried out and adequately monitored first in urban, suburban, industrial, or agricultural areas.[131] Likewise, Jeff McMahan argues that since humans "are already causing massive, precipitate changes in the natural world," humans should favor those changes that would promote the survival "of herbivorous rather than carnivorous species."[105] Peter Vallentyne, a philosopher, suggests that, while humans should not eliminate predators in nature, they can intervene to help prey in more limited ways. In the same way that humans help humans in need when the cost to us is small, humans might help some wild animals at least in limited circumstances.[132]

Potential conflict between animal rights and environmentalism

It has been argued that the environmentalist goal of preserving certain abstract entities such as species and ecosystems and a policy of non-interference in regard to natural processes is incompatible with animal rights views, which place the welfare and interests of individual animals at the center of concern.[133][134][135] Examples include environmentalists supporting hunting for species population control, while animal rights advocates oppose it;[71] animal rights advocates arguing for the extinction or reengineering of carnivores or r-strategist species, while deep ecologists defend their right to be and flourish as they are;[114][136] animal rights advocates defending the reduction of wildlife habitats or arguing against their expansion out of concern that most animal suffering takes place within them, while environmentalists want to safeguard and expand them.[137][138] Oscar Horta argues that there are instances where environmentalists and animal rights advocates may both support approaches that would consequently reduce wild animal suffering.[138]

Ecology as intrinsically valuable

Environmental ethicist Holmes Rolston III argues that only unnatural animal suffering is morally bad and that humans do not have a duty to intervene in cases of suffering caused by natural processes.[139] He celebrates carnivores in nature because of the significant ecological role they play.[136] Others have argued that the reason that humans have a duty to protect other humans from predation is that humans are part of the cultural world rather than the natural world and so different rules apply to them in these situations.[136][140] Some writers argue that prey animals are fulfilling their natural function, and thus flourishing when they are preyed upon or otherwise die since this allows natural selection to work.[118]

Yves Bonnardel, an animal rights philosopher, has criticized this view, as well as the concept of nature, which he describes as an "ideological tool" that places humans in a superior position above other animals, who exist only to perform certain ecosystem functions, such as a rabbit being food for a wolf. Bonnardel compares this with the religious idea that a slaves exist for their masters, or that woman exists for the sake of man. He argues that animals as individuals all have an interest in living.[141]

Wild animal suffering as a reductio ad absurdum

The idea that animal rights imply a moral obligation to intervene in nature has been used as a reductio ad absurdum against the position that animals have rights.[12] It has been argued that if animals who are subject to predation did have rights, people would be obliged to intervene in nature to protect them, but this is claimed to be absurd.[115][142] An objection to this argument is that people do not see intervening in the natural world to save other people from predation as absurd and so this could be seen to involve treating animals differently in this situation without justification, which is due to speciesism.[143]

Animal rights philosopher Steve F. Sapontzis asserts that the major reason why people would find opposing predation absurd is an "appeal to 'nature' and to the 'rightful place of things'". He contends that the same line of argument has notably been used against the emancipation of black people, against birth control and against women's rights. He also argues that in all the ways in which absurdity is defined (logical, factual, contextual, theoretical, unnatural, practical absurdity), one cannot effect an effective reductio ad absurdum against the animal rights movement.[144]

Nature as idyllic

The idyllic view of nature is described as a widely held view that happiness in nature is prevalent.[6][7] Oscar Horta argues that even though many people are aware of the harms that animals in the wild experience, such as predation, starvation and disease, as well as recognizing that these animals may suffer as a result of these harms, they don't conclude from this that wild animals have bad enough lives to imply that nature is not a happy place. Horta also contends that a romantic conception of nature has significant implications for attitudes people have towards animals in the wild, as holders of the view may oppose interventions to reduce suffering.[6]

Bob Fischer argues that many wild animals may have "net negative" lives (experiencing more pain than pleasure), even in the absence of human activity. However, Fischer argues that if many animals have net negative lives, then what is good for the animal, as an individual, may not be good for its species, other species, the climate or the preservation of biodiversity; for example, some animals may have to have their populations massively reduced and controlled and some species, such as parasites or predators, eliminated entirely.[145]

Intervention as hubris

Some writers have argued that interventions to reduce wild animal suffering would be an example of arrogance, hubris, or playing God, as such interventions could potentially have disastrous unforeseen consequences. They are also sceptical of the competence of humans when it comes to making correct moral judgements, as well as human fallibility. Additionally, they contend that the moral stance of humans and moral agency can lead to the imposition of anthropocentric or paternalistic values on others. To support these claims, they use the history of human negative impacts on nature, including species extinctions, wilderness and resource depletion, as well as climate change. From this, they conclude that the best way that humans can help animals in the wild is through the preservation of larger wilderness areas and by reducing the human sphere of influence on nature.[13]

Critics of this position, such as Beril Sözmen, argue that human negative impacts are not inevitable and that, until recently, interventions were not undertaken with the goal of improving the well-being of individual animals in the wild. Furthermore, she contends that such examples of anthropogenic harms are not the consequence of misguided human intervention gone awry, but are actually the result of human agriculture and industry, which do not consider, or do not care, about their impact on nature and animals in the wild. Sözmen also asserts that the holders of this position may view that nature as exists in a delicate state of balance and have an overly romantic view of the lives of animals in the wild and, that she contends, actually contain vast amounts of suffering.[13] Martha Nussbaum argues that because humans are constantly intervening in nature, the central question should be what form should these interventions take, rather than whether interventions should take place, arguing that "intelligently respectful paternalism is vastly superior to neglect".[128]: 377

Laissez-faire

A laissez-faire view, which holds that humans should not harm animals in the wild, but do not have an obligation to aid these individuals when in need, has been defended by Tom Regan, Elisa Aaltola, Clare Palmer and Ned Hettinger. Regan argued that the suffering animals inflict on each other should not be a concern of ethically motivated wildlife management and that these wildlife managers should instead focus on letting animals in the wild exist as they are, with no human predation, and to "carve out their own destiny".[14] Aaltola similarly argues that predators should be left to flourish, despite the suffering that they cause to the animals that they predate.[15] Palmer endorses a variant of this position, which claims that humans may have an obligation to assist wild animals if humans are responsible for their situation.[146] Hettinger argues for laissez-faire based on the environmental value of "Respect for an Independent Nature".[147]

Catia Faria argues that following the principle that humans should only help individuals when they are being harmed by humans, rather than by natural processes, would also mean refusing to help humans and companion animals when they suffer due to natural processes, however, this implication does not seem acceptable to most people and she asserts that there are strong reasons to help these individuals when humans have capacity to do so. Faria argues that there is an obligation to help animals in the wild suffering in similar situations and, as a result, the laissez-faire view does not hold up.[148] Similarly, Steven Nadler argues that it is morally wrong to refuse help to animals in the wild regardless of whether humans are indirectly or directly responsible for their suffering, as the same arguments used to decline aid to humans who were suffering due to natural harms such as famine, a tsunami or pneumonia would be considered immoral. He concludes that if the only thing that is morally relevant is an individual's capacity to suffer, there is no relevant moral difference between humans and other animals suffering in these situations.[129] In the same vein, Steve F. Sapontizis asserts that: "When our interests or the interests of those we care for will be hurt, we do not recognize a moral obligation to 'let nature take its course'".[149]

Wild animal sovereignty

Some writers, such as the animal rights philosophers Sue Donaldson and Will Kymlicka, in Zoopolis, argue that humans should not perform large interventions to help animals in the wild. They assert that these interventions would be taking away their sovereignty, by removing the ability for these animals to govern themselves.[150] Christiane Bailey asserts that certain wild animals, especially prosocial animals, have sufficient criteria to be considered as moral agents, that is to say, individuals capable of making moral judgments and who have responsibilities. She argues that aiding them would be reducing wild animals to beings incapable of making decisions for themselves.[151]

Oscar Horta emphasizes the fact that although some individuals may form sovereign groups, the vast majority of wild animals are either solitary or re-selectors, whose population size varies greatly from year to year. He contends that most of their interactions would be amensalism, commensalism, antagonism or competition. Therefore, the majority of animals in wild would not form sovereign communities if humans use the criteria established by Donaldson and Kymlicka.[152]

Analogy with colonialism

Estiva Reus asserts that a comparison exists, from a certain perspective, between the spirit which animated the defenders of colonialism who saw it as necessary human progress for "backward peoples", and the idea which inspires writers who argue for reforming nature in the interest of wild animals: the proponents of the two positions consider that they have the right and the duty, because of their superior skills, to model the existence of beings unable to remedy by their own means the evils which overwhelm them.[153]

Thomas Lepeltier, a historian and writer on animal ethics, argues that "if colonization is to be criticized, it is because, beyond the rhetoric, it was an enterprise of spoliation and exaction exercised with great cruelty."[154] He also contends that writers who advocate for helping wild animals do not do so for their own benefit because they would have nothing to gain by helping these individuals. Lepeltier goes on to assert that the advocates for reducing wild animal suffering would be aware of their doubts about how best to help these individuals and that they would not act by considering them as rudimentary and simple to understand beings, contrary to the vision that the former colonizers had of colonized populations.[154]

Intervention in practice

Proposed forms of assistance

Some proposed forms of assistance—many of which are already employed to help individual animals in the wild in limited ways—include providing medical care to sick and injured animals,[121][155][106] vaccinating animals to prevent disease, taking care of orphaned animals, rescuing animals who are trapped, or in natural disasters, taking care of the needs of animals who are starving or thirsty, sheltering animals who are suffering due to weather conditions[127] and using contraception to regulate population sizes in a way that might reduce suffering,[156] rather than cause additional suffering.[157] When it comes to reducing suffering as a result of predation, removing predators from wild areas[158][159] and refraining from reintroducing predators have both been advocated for.[71][160] For reducing predation of wild animals due to cats and dogs, it is recommended that companion animals should always be sterilized to prevent the existence of feral animals and that cats should be kept indoors and dogs kept on a leash, unless in designated areas.[161]

Suggested forms of future assistance, based on further research, feasibility and whether interventions could be carried out without increasing suffering overall, include using gene drives and CRISPR to reduce the suffering of members of r-strategist species,[162] arranging the gradual extinction of carnivorous species,[54] as well as using biotechnology to eradicate suffering in wild animals.[19][163]

Welfare biology

Welfare biology is a proposed research field for studying the welfare of animals, with a particular focus on their relationship with natural ecosystems.[164] It was first advanced in 1995 by Yew-Kwang Ng, who defined it as "the study of living things and their environment with respect to their welfare (defined as net happiness, or enjoyment minus suffering)".[70] Such research is intended to promote concern for animal suffering in the wild and to establish effective actions that can be undertaken to help these individuals in the future.[165][166]

History of interventions

The Bishnoi, a Hindu sect founded in the 15th century, have a tradition of feeding wild animals.[167] Some Bishnoi temples also act as rescue centres, where priests take care of injured animals; a few of these individuals are returned to the wild, while others remain, roaming freely in the temple compounds.[168] The Borana Oromo people leave out water overnight for wild animals to drink because they believe that the animals have the right to drinking water.[169]

In 2002, the Australian Government authorized the killing of 15,000, out of 100,000, kangaroos who were trapped in a fenced-in national military base and suffering in a state of illness, misery and starvation.[170] In 2016, 350 starving hippos and buffaloes at Kruger National Park were killed by park rangers; one of the motives for the action was to prevent them from suffering as they died.[171]

Rescues of multiple animals in the wild have taken place: in 1988, the US and Soviet governments collaborated in Operation Breakthrough, to free three gray whales who were trapped in pack ice off the coast of Alaska;[172] in 2018, a team of BBC filmmakers dug a ramp in the snow to allow a group of penguins to escape a ravine in Antarctica;[173] in 2019, 2,000 baby flamingos were rescued during a drought in South Africa;[174] during the 2019–20 Australian bushfire season, a number of fire-threatened wild animals were rescued;[175] in 2020, 120 pilot whales, who were beached, were rescued in Sri Lanka;[176] in 2021, 1,700 Cape cormorant chicks, who had been abandoned by their parents, were rescued in South Africa;[177] in the same year, nearly 5,000 cold-stunned sea turtles were rescued in Texas.[178]

Vaccination programs have been successfully implemented to prevent rabies and tuberculosis in wild animals.[179] Wildlife contraception has been used to reduce and stabilize populations of wild horses, white-tailed deer, American bison and African elephants.[157][180]

Future prospects

Risks

Spreading wild animal suffering beyond Earth

Several researchers and non-profit organizations have raised concern that human civilization may cause wild animal suffering outside Earth. For example, wild habitats may be created—or allowed to happen—on extraterrestrial colonies like terraformed planets.[181][182] Another example of a potential realization of the risk is directed panspermia where the initial microbial population eventually evolves into sentient organisms.[183][184]

Spreading sentient wild animals beyond Earth may constitute a suffering risk, as this could potentially lead to an immense increase in wild animal suffering in existence.[185]

Cultural depictions

Wildlife documentaries

Criticism of portrayals of wild animal suffering

It has been argued that much of people's knowledge about wild animals comes from wildlife documentaries, which have been described as non-representative of the reality of wild animal suffering because they underrepresent uncharismatic animals who may have the capacity to suffer, such as animals who are preyed upon, as well as small animals and invertebrates.[186] In addition, it is claimed that such documentaries focus on adult animals, while the majority of animals who likely suffer the most, die before reaching adulthood;[186] that wildlife documentaries don't generally show animals suffering from parasitism;[119]: 47 that such documentaries can leave viewers with the false impression that animals who have been attacked by predators and suffered serious injury survived and thrived afterwards;[187] and that much of the particularly violent incidences of predation are not included.[188] The broadcaster David Attenborough has stated: "People who accuse us of putting in too much violence, [should see] what we leave on the cutting-room floor.[189]

It is also contended that wildlife documentaries present nature as a spectacle to be passively consumed by viewers, as well as a sacred and unique place that needs protection. Additionally, attention is drawn to how hardships that are experienced by animals are portrayed in a way that give the impression that wild animals, through adaptive processes, are able to overcome these sources of harm. However, the development of such adaptive traits takes place over a number of generations of individuals who will likely experience much suffering and hardship in their lives, while passing down their genes.[190]

David Pearce, a transhumanist and advocate for technological solutions for reducing the suffering of wild animals, is highly critical of how wildlife documentaries, which he refers to as "animal snuff-movies", represent wild animal suffering:

Nature documentaries are mostly travesties of real life. They entertain and edify us with evocative mood-music and travelogue-style voice-overs. They impose significance and narrative structure on life's messiness. Wildlife shows have their sad moments, for sure. Yet suffering never lasts very long. It is always offset by homely platitudes about the balance of Nature, the good of the herd, and a sort of poor-man's secular theodicy on behalf of Mother Nature which reassures us that it's not so bad after all. ... That's a convenient lie. ... Lions kill their targets primarily by suffocation; which will last minutes. The wolf pack may start eating their prey while the victim is still conscious, though hamstrung. Sharks and the orca basically eat their prey alive; but in sections for the larger prey, notably seals.[191]

Pearce also argues, through analogy, how the idea of intelligent aliens creating stylised portrayals of human deaths for popular entertainment would be considered abhorrent; he asserts that, in reality, this is the role that humans play when creating wildlife documentaries.[191]

Clare Palmer asserts that even when wildlife documentaries contain vivid images of wild animal suffering, they don't motivate a moral or practical response in the way that companion animals, such as dogs or cats, suffering in similar situations would and most people instinctively adopt the position of laissez-faire: allowing suffering to take its course, without intervention.[192]

Non-intervention as a filmmaking rule

The question of whether wildlife documentary filmmakers should intervene to help animals is a topic of much debate.[193] It has been described as a "golden rule" of such filmmaking to observe animals, but not intervene.[194] The rule is occasionally broken, with BBC documentary crews rescuing some stranded baby turtles in 2016 and rescuing a group of penguins trapped in a ravine in 2018;[195] the latter decision was defended by other wildlife documentary filmmakers.[173] Filmmakers following the rule have been criticized for filming dying animals, such as an elephant dying of thirst, without helping them.[195]

In fiction

Herman Melville, in Moby-Dick, published in 1851, describes the sea as a place of "universal cannibalism", where "creatures prey upon each other, carrying on eternal war since the world began"; this is illustrated by a later scene depicting sharks consuming their own entrails.[196]

The fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen contain depictions of the suffering of animals due to natural processes and their rescues by humans. The titular character in "Thumbelina" encounters a seemingly dead frozen swallow. Thumbelina feels sorry for the bird and her companion the mole states: "What a wretched thing it is to be born a little bird. Thank goodness none of my children can be a bird, who has nothing but his 'chirp, chirp', and must starve to death when winter comes along."[197] However, Thumbelina discovers that the swallow isn't actually dead and manages to nurse them back to health.[198] In "The Ugly Duckling", the bitter winter cold causes the duckling to become frozen in an icy pond; the duckling is rescued by a farmer who breaks the ice and takes the duckling to his home to be resuscitated.[199]

In the 1923 book Bambi, a Life in the Woods, Felix Salten portrays a world where predation and death are continuous: a sick young hare is killed by crows, a pheasant and a duck are killed by foxes, a mouse is killed by an owl and a squirrel describes how their family members were killed by predators.[200] The 1942 Disney adaptation has been criticized for inaccurately portraying a world where predation and death are no longer emphasized, creating a "fantasy of nature cleansed of the traumas and difficulties that may trouble children and that adults prefer to avoid."[201] The film version has also been criticized for unrealistically portraying nature undisturbed by humans as an idyllic place, made up of interspecies friendships, with Bambi's life undisturbed by many of the harms routinely experienced by his real-life counterparts, such as starvation, predation, bovine tuberculosis and chronic wasting disease.[186]

John Wyndham's character Zelby, in the 1957 book The Midwich Cuckoos, describes nature as "ruthless, hideous, and cruel beyond belief" and observes that the lives of insects are "sustained only by intricate processes of fantastic horror".[202]

In Watership Down, published in 1972, Richard Adams compares the hardship experienced by animals in winter to the suffering experienced by poor humans, stating: "For birds and animals, as for poor men, winter is another matter. Rabbits, like most wild animals, suffer hardship."[203] Adams also describes rabbits as being more susceptible to disease in the winter.[203]

In the philosopher Nick Bostrom's short story "Golden", the main character Albert, an uplifted golden retriever, observes that humans observe nature from an ecologically aesthetic perspective which disregards the suffering of the individuals who inhabit "healthy" ecosystems;[204] Albert also asserts that it is a taboo in the animal rights movement that the majority of the suffering experienced by animals is due to natural processes and that "[a]ny proposal for remedying this situation is bound to sound utopian, but my dream is that one day the sun will rise on Earth and all sentient creatures will greet the new day with joy."[205]

The character Lord Vetinari, in Terry Pratchett's Unseen Academicals, in a speech, tells how he once observed a salmon being consumed alive by a mother otter and her children feeding on the salmon's eggs. He sarcastically describes "[m]other and children dining upon mother and children" as one of "nature's wonders", using it as an example of how evil is "built into the very nature of the universe".[206] This depiction of evil has been described as non-traditional because it expresses horror at the idea that evil has been designed as a feature of the universe.[207]

In poetry

Homer, in the Odyssey, employs the simile of a stag who, as a victim, is wounded by a human hunter and is then devoured by jackals, who themselves are frightened away by a scavenging lion.[208] In the epigram "The Swallow and the Grasshopper", attributed to Euenus, the poet writes of a swallow feeding a grasshopper to its young, remarking: "wilt not quickly cast it loose? for it is not right nor just that singers should perish by singers' mouths."[209]

Al-Ma'arri wrote of the kindness of giving water to birds and speculated whether there was a future existence where innocent animals would experience happiness to remedy the suffering they experience in this world. In the Luzūmiyyāt, he included a poem addressed to the wolf, who: "if he were conscious of his bloodguiltiness, would rather have remained unborn."[210]

In "On Poetry: A Rhaposdy", written in 1733, Jonathan Swift argues that Hobbes proved that all creatures exist in a state of eternal war and uses predation by different animals as evidence of this: "A Whale of moderate Size will draw / A Shole of Herrings down his Maw. / A Fox with Geese his Belly crams; / A Wolf destroys a thousand Lambs."[211] Voltaire makes similar descriptions of predation in his "Poem on the Lisbon Disaster", published in 1756, arguing: "Elements, animals, humans, everything is at war".[212] Voltaire also asserts that "all animals [are] condemned to live, / All sentient things, born by the same stern law, / Suffer like me, and like me also die."[213]

In William Blake's Vala, or The Four Zoas, the character Enion laments the cruelty of nature,[214] observing how ravens cry out, but don't receive pity and how sparrows and robins starve to death in the winter. Enion also mourns how wolves and lions reproduce in a state of love, then abandon their young to the wilds and how a spider labours to create a web, awaiting a fly, but then is consumed by a bird.[215]

Erasmus Darwin in The Temple of Nature, published posthumously in 1803, observes the struggle for existence, describing how different animals feed upon each other: "The towering eagle, darting from above, / Unfeeling rends the inoffensive dove [...] Nor spares, enamour'd of his radiant form, / The hungry nightingale the glowing worm" and how parasitic animals, like botflies, reproduce, their young feeding inside the living bodies of other animals: "Fell Oestrus buries in her rapid course / Her countless brood in stag, or bull, or horse; / Whose hungry larva eats its living way, / Hatch'd by the warmth, and issues into day."[216]: 154–155 He also refers to the world as "one great Slaughter-house".[216]: 159 The poem has been used as an example of how Erasmus Darwin predicted evolutionary theory.[217]

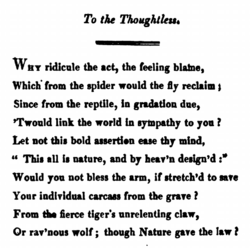

Isaac Gompertz, the brother of Lewis Gompertz, in his 1813 poem "To the Thoughtless", criticises the assertion that human consumption of other animals is justified because it is designed that way by nature, inviting the reader to imagine themselves being predated by an animal and to consider whether they would want to have their life saved, in the same way an animal being preyed upon—such as a fly attacked by a spider—would, despite predation being part of nature-given law.[218]

In the 1818 poem "Epistle to John Hamilton Reynolds", John Keats retells to John Hamilton Reynolds how one evening he was by the ocean, when he saw: "Too far into the sea; where every maw / The greater on the less feeds evermore" and observes that there exists an "eternal fierce destruction" at the core of the world: "The Shark at savage prey — the hawk at pounce, — / The gentle Robin, like a Pard or Ounce, / Ravening a worm".[219] The poem has been cited as an example of Erasmus Darwin's writings on Keats.[220]

In 1850, Alfred Tennyson published the poem "In Memoriam A.H.H.", which contained the expression "Nature, red in tooth and claw"; this phrase has since become commonly used as a shorthand to refer to the extent of suffering in nature.[221] In his 1855 poem "Maud", Tennyson described nature as irredeemable because of the theft and predation it intrinsically contains: "For nature is one with rapine, a harm no preacher can heal; / The Mayfly is torn by the swallow, the sparrow spear'd by the shrike, / And the whole little wood where I sit is a world of plunder and prey."[222]

Edwin Arnold in The Light of Asia, a narrative poem published in 1879 about the life of Prince Gautama Buddha, describes how originally the prince saw the "peace and plenty" of nature, but upon closer inspection he observed: "Life living upon death. So the fair show / Veiled one vast, savage, grim conspiracy / Of mutual murder, from the worm to man".[223] It has been asserted that the Darwinian struggle depicted in the poem comes more from Arnold than Buddhist tradition.[224]

See also

- Emotion in animals

- God's utility function

- Natural evil

- Pain in animals

- Pain in amphibians

- Pain in cephalopods

- Pain in crustaceans

- Pain in invertebrates

- Pain in fish

- The Problem of Pain

- Suffering-focused ethics

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Tomasik, Brian (2015-11-02). "The Importance of Wild-Animal Suffering" (in en). Relations. Beyond Anthropocentrism 3 (2): 133–152. doi:10.7358/rela-2015-002-toma. ISSN 2280-9643. https://www.ledonline.it/index.php/Relations/article/view/880.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Faria, Catia; Paez, Eze (2015-05-11). "Animals in Need: the Problem of Wild Animal Suffering and Intervention in Nature" (in en). Relations. Beyond Anthropocentrism 3 (1): 7–13. ISSN 2280-9643. https://www.ledonline.it/index.php/Relations/article/view/816.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Wilcox, Christie (2011-12-04). "Bambi or Bessie: Are wild animals happier?" (in en). https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/bambi-or-bessie-are-wild-animals-happier/.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Horta, Oscar (2014-11-25). "Egalitarianism and Animals". Between the Species 19 (1). https://digitalcommons.calpoly.edu/bts/vol19/iss1/5.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Dawkins, Richard (1995). Chapter 4: God's Utility Function. London: Orion Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-297-81540-2.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 Horta, Oscar (2010). "Debunking the Idyllic View of Natural Processes: Population Dynamics and Suffering in the Wild". Télos 17 (1): 73–88. https://www.stafforini.com/docs/Horta%20-%20Debunking%20the%20idyllic%20view%20of%20natural%20processes.pdf.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Iglesias, Alejandro Villamor (2018). "The overwhelming prevalence of suffering in Nature". Revista de Bioética y Derecho 2019: 181–195. https://www.redalyc.org/jatsRepo/783/78355381012/html/index.html.

- ↑ For discussion of wild animal suffering and its relation to the problem of evil see:

- Darwin, Charles (September 1993). Barlow, Nora. ed. The Autobiography of Charles Darwin: 1809-1882. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 90. ISBN 978-0393310696.

- Lewis, C. S. (2015). The Problem of Pain. HarperOne. ISBN 9780060652968. https://archive.org/details/problemofpain00lewi_0.

- Murray, Michael (April 30, 2011). Nature Red in Tooth and Claw: Theism and the Problem of Animal Suffering. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199596324.

- Gould, Stephen (February 1982). "Nonmoral Nature". Natural History 91 (2): 19–26. http://www.pagefarm.net--www.pagefarm.net/ap/PDFs/nmn.pdf. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- McMahan, Jeff (2013). "The Moral Problem of Predation". in Chignell, Andrew; Cuneo, Terence; Halteman, Matt. Philosophy Comes to Dinner: Arguments on the Ethics of Eating. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415806831. http://jeffersonmcmahan.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/The-Moral-Problem-of-Predation.pdf.

- ↑

For academic discussion of wild animal suffering and its alleviation from a secular standpoint see:

- McMahan, Jeff (2013). "The Moral Problem of Predation". in Chignell, Andrew; Cuneo, Terence; Halteman, Matt. Philosophy Comes to Dinner: Arguments on the Ethics of Eating. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415806831. http://jeffersonmcmahan.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/The-Moral-Problem-of-Predation.pdf.

- Ng, Yew-Kwang (1995). "Towards Welfare Biology: Evolutionary Economics of Animal Consciousness and Suffering". Biology and Philosophy 10 (3): 255–285. doi:10.1007/BF00852469. https://www.ntu.edu.sg/home/ykng/Towards%20Welfare%20Biology-1995.pdf.

- Dorado, Daniel (2015). "Ethical Interventions in the Wild. An Annotated Bibliography". Relations. Beyond Anthropocentrism 3 (2): 219–238. doi:10.7358/rela-2015-002-dora. http://www.ledonline.it/index.php/Relations/article/view/887. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- Moen, Ole Martin (2016). "The Ethics of Wild Animal Suffering". Etikk I Praksis - Nordic Journal of Applied Ethics 10: 1–14. doi:10.5324/eip.v10i1.1972. http://www.olemartinmoen.com/wp-content/uploads/TheEthicsofWildAnimalSuffering.pdf. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- Horta, Oscar (2015). "The Problem of Evil in Nature: Evolutionary Bases of the Prevalence of Disvalue". Relations. Beyond Anthropocentrism 3 (1): 17–32. doi:10.7358/rela-2015-001-hort. http://www.ledonline.it/index.php/Relations/article/view/825. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- Torres, Mikel (2015). "The Case for Intervention in Nature on Behalf of Animals: A Critical Review of the Main Arguments against Intervention". Relations. Beyond Anthropocentrism 3 (1): 33–49. doi:10.7358/rela-2015-001-torr. http://www.ledonline.it/index.php/Relations/article/view/824. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- Cunha, Luciano Carlos (2015). "If Natural Entities Have Intrinsic Value, Should We Then Abstain from Helping Animals Who Are Victims of Natural Processes?". Relations. Beyond Anthropocentrism 3 (1): 51–63. doi:10.7358/rela-2015-001-cunh. http://www.ledonline.it/index.php/Relations/article/view/823. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- Tomasik, Brian (2015). "The Importance of Wild-Animal Suffering". Relations. Beyond Anthropocentrism 3 (2): 133–152. doi:10.7358/rela-2015-002-toma. http://www.ledonline.it/index.php/Relations/article/view/880. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- Pearce, David (2015). "A Welfare State For Elephants? A Case Study of Compassionate Stewardship". Relations. Beyond Anthropocentrism 3 (2): 153–164. doi:10.7358/rela-2015-002-pear. http://www.ledonline.it/index.php/Relations/article/view/881. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- Paez, Eze (2015). "Refusing Help and Inflicting Harm. A Critique of the Environmentalist View". Relations. Beyond Anthropocentrism 3 (2): 165–178. doi:10.7358/rela-2015-002-paez. http://www.ledonline.it/index.php/Relations/article/view/882. Retrieved 8 May 2016.