Asymptotic safety in quantum gravity

Topic: Physics

From HandWiki - Reading time: 24 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 24 min

| Beyond the Standard Model |

|---|

|

| Standard Model |

Asymptotic safety (sometimes also referred to as nonperturbative renormalizability) is a concept in quantum field theory which aims at finding a consistent and predictive quantum theory of the gravitational field. Its key ingredient is a nontrivial fixed point of the theory's renormalization group flow which controls the behavior of the coupling constants in the ultraviolet (UV) regime and renders physical quantities safe from divergences. Although originally proposed by Steven Weinberg to find a theory of quantum gravity, the idea of a nontrivial fixed point providing a possible UV completion can be applied also to other field theories, in particular to perturbatively nonrenormalizable ones. In this respect, it is similar to quantum triviality.

The essence of asymptotic safety is the observation that nontrivial renormalization group fixed points can be used to generalize the procedure of perturbative renormalization. In an asymptotically safe theory the couplings do not need to be small or tend to zero in the high energy limit but rather tend to finite values: they approach a nontrivial UV fixed point. The running of the coupling constants, i.e. their scale dependence described by the renormalization group (RG), is thus special in its UV limit in the sense that all their dimensionless combinations remain finite. This suffices to avoid unphysical divergences, e.g. in scattering amplitudes. The requirement of a UV fixed point restricts the form of the bare action and the values of the bare coupling constants, which become predictions of the asymptotic safety program rather than inputs.

As for gravity, the standard procedure of perturbative renormalization fails since Newton's constant, the relevant expansion parameter, has negative mass dimension rendering general relativity perturbatively nonrenormalizable. This has driven the search for nonperturbative frameworks describing quantum gravity, including asymptotic safety which – in contrast to other approaches – is characterized by its use of quantum field theory methods, without depending on perturbative techniques, however. At the present time, there is accumulating evidence for a fixed point suitable for asymptotic safety, while a rigorous proof of its existence is still lacking.

Motivation

Gravity, at the classical level, is described by Einstein's field equations of general relativity, . These equations combine the spacetime geometry encoded in the metric with the matter content comprised in the energy–momentum tensor . The quantum nature of matter has been tested experimentally, for instance quantum electrodynamics is by now one of the most accurately confirmed theories in physics. For this reason quantization of gravity seems plausible, too. Unfortunately the quantization cannot be performed in the standard way (perturbative renormalization): Already a simple power-counting consideration signals the perturbative nonrenormalizability since the mass dimension of Newton's constant is . The problem occurs as follows. According to the traditional point of view renormalization is implemented via the introduction of counterterms that should cancel divergent expressions appearing in loop integrals. Applying this method to gravity, however, the counterterms required to eliminate all divergences proliferate to an infinite number. As this inevitably leads to an infinite number of free parameters to be measured in experiments, the program is unlikely to have predictive power beyond its use as a low energy effective theory.

It turns out that the first divergences in the quantization of general relativity which cannot be absorbed in counterterms consistently (i.e. without the necessity of introducing new parameters) appear already at one-loop level in the presence of matter fields.[1] At two-loop level the problematic divergences arise even in pure gravity.[2] In order to overcome this conceptual difficulty the development of nonperturbative techniques was required, providing various candidate theories of quantum gravity. For a long time the prevailing view has been that the very concept of quantum field theory – even though remarkably successful in the case of the other fundamental interactions – is doomed to failure for gravity. By way of contrast, the idea of asymptotic safety retains quantum fields as the theoretical arena and instead abandons only the traditional program of perturbative renormalization.

History

After having realized the perturbative nonrenormalizability of gravity, physicists tried to employ alternative techniques to cure the divergence problem, for instance resummation or extended theories with suitable matter fields and symmetries, all of which come with their own drawbacks. In 1976, Steven Weinberg proposed a generalized version of the condition of renormalizability, based on a nontrivial fixed point of the underlying renormalization group (RG) flow for gravity.[3] This was called asymptotic safety.[4][5] The idea of a UV completion by means of a nontrivial fixed point of the renormalization groups had been proposed earlier by Kenneth G. Wilson and Giorgio Parisi in scalar field theory[6][7] (see also Quantum triviality). The applicability to perturbatively nonrenormalizable theories was first demonstrated explicitly for the non-linear sigma model[8] and for a variant of the Gross–Neveu model.[9]

As for gravity, the first studies concerning this new concept were performed in spacetime dimensions in the late seventies. In exactly two dimensions there is a theory of pure gravity that is renormalizable according to the old point of view. (In order to render the Einstein–Hilbert action dimensionless, Newton's constant must have mass dimension zero.) For small but finite perturbation theory is still applicable, and one can expand the beta-function (-function) describing the renormalization group running of Newton's constant as a power series in . Indeed, in this spirit it was possible to prove that it displays a nontrivial fixed point.[4]

However, it was not clear how to do a continuation from to dimensions as the calculations relied on the smallness of the expansion parameter . The computational methods for a nonperturbative treatment were not at hand by this time. For this reason the idea of asymptotic safety in quantum gravity was put aside for some years. Only in the early 90s, aspects of dimensional gravity have been revised in various works, but still not continuing the dimension to four.

As for calculations beyond perturbation theory, the situation improved with the advent of new functional renormalization group methods, in particular the so-called effective average action (a scale dependent version of the effective action). Introduced in 1993 by Christof Wetterich and Tim R Morris for scalar theories,[10][11] and by Martin Reuter and Christof Wetterich for general gauge theories (on flat Euclidean space),[12] it is similar to a Wilsonian action (coarse grained free energy)[6] and although it is argued to differ at a deeper level,[13] it is in fact related by a Legendre transform.[11] The cutoff scale dependence of this functional is governed by a functional flow equation which, in contrast to earlier attempts, can easily be applied in the presence of local gauge symmetries also.

In 1996, Martin Reuter constructed a similar effective average action and the associated flow equation for the gravitational field.[14] It complies with the requirement of background independence, one of the fundamental tenets of quantum gravity. This work can be considered an essential breakthrough in asymptotic safety related studies on quantum gravity as it provides the possibility of nonperturbative computations for arbitrary spacetime dimensions. It was shown that at least for the Einstein–Hilbert truncation, the simplest ansatz for the effective average action, a nontrivial fixed point is indeed present.

These results mark the starting point for many calculations that followed. Since it was not clear in the pioneer work by Martin Reuter to what extent the findings depended on the truncation ansatz considered, the next obvious step consisted in enlarging the truncation. This process was initiated by Roberto Percacci and collaborators, starting with the inclusion of matter fields.[15] Up to the present many different works by a continuously growing community – including, e.g., - and Weyl tensor squared truncations – have confirmed independently that the asymptotic safety scenario is actually possible: The existence of a nontrivial fixed point was shown within each truncation studied so far.[16] Although still lacking a final proof, there is mounting evidence that the asymptotic safety program can ultimately lead to a consistent and predictive quantum theory of gravity within the general framework of quantum field theory.

Main ideas

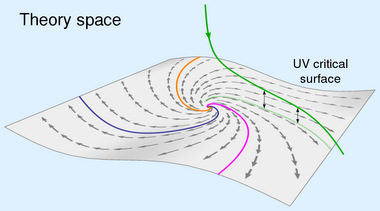

Theory space

The asymptotic safety program adopts a modern Wilsonian viewpoint on quantum field theory. Here the basic input data to be fixed at the beginning are, firstly, the kinds of quantum fields carrying the theory's degrees of freedom and, secondly, the underlying symmetries. For any theory considered, these data determine the stage the renormalization group dynamics takes place on, the so-called theory space. It consists of all possible action functionals depending on the fields selected and respecting the prescribed symmetry principles. Each point in this theory space thus represents one possible action. Often one may think of the space as spanned by all suitable field monomials. In this sense any action in theory space is a linear combination of field monomials, where the corresponding coefficients are the coupling constants, . (Here all couplings are assumed to be dimensionless. Couplings can always be made dimensionless by multiplication with a suitable power of the RG scale.)

Renormalization group flow

The renormalization group (RG) describes the change of a physical system due to smoothing or averaging out microscopic details when going to a lower resolution. This brings into play a notion of scale dependence for the action functionals of interest. Infinitesimal RG transformations map actions to nearby ones, thus giving rise to a vector field on theory space. The scale dependence of an action is encoded in a "running" of the coupling constants parametrizing this action, , with the RG scale . This gives rise to a trajectory in theory space (RG trajectory), describing the evolution of an action functional with respect to the scale. Which of all possible trajectories is realized in Nature has to be determined by measurements.

Taking the UV limit

The construction of a quantum field theory amounts to finding an RG trajectory which is infinitely extended in the sense that the action functional described by is well-behaved for all values of the momentum scale parameter , including the infrared limit and the ultraviolet (UV) limit . Asymptotic safety is a way of dealing with the latter limit. Its fundamental requirement is the existence of a fixed point of the RG flow. By definition this is a point in the theory space where the running of all couplings stops, or, in other words, a zero of all beta-functions: for all . In addition that fixed point must have at least one UV-attractive direction. This ensures that there are one or more RG trajectories which run into the fixed point for increasing scale. The set of all points in the theory space that are "pulled" into the UV fixed point by going to larger scales is referred to as UV critical surface. Thus the UV critical surface consists of all those trajectories which are safe from UV divergences in the sense that all couplings approach finite fixed point values as . The key hypothesis underlying asymptotic safety is that only trajectories running entirely within the UV critical surface of an appropriate fixed point can be infinitely extended and thus define a fundamental quantum field theory. It is obvious that such trajectories are well-behaved in the UV limit as the existence of a fixed point allows them to "stay at a point" for an infinitely long RG "time".

With regard to the fixed point, UV-attractive directions are called relevant, UV-repulsive ones irrelevant, since the corresponding scaling fields increase and decrease, respectively, when the scale is lowered. Therefore, the dimensionality of the UV critical surface equals the number of relevant couplings. An asymptotically safe theory is thus the more predictive the smaller is the dimensionality of the corresponding UV critical surface.

For instance, if the UV critical surface has the finite dimension it is sufficient to perform only measurements in order to uniquely identify Nature's RG trajectory. Once the relevant couplings are measured, the requirement of asymptotic safety fixes all other couplings since the latter have to be adjusted in such a way that the RG trajectory lies within the UV critical surface. In this spirit the theory is highly predictive as infinitely many parameters are fixed by a finite number of measurements.

In contrast to other approaches, a bare action which should be promoted to a quantum theory is not needed as an input here. It is the theory space and the RG flow equations that determine possible UV fixed points. Since such a fixed point, in turn, corresponds to a bare action, one can consider the bare action a prediction in the asymptotic safety program. This may be thought of as a systematic search strategy among theories that are already "quantum" which identifies the "islands" of physically acceptable theories in the "sea" of unacceptable ones plagued by short distance singularities.

Gaussian and non-Gaussian fixed points

A fixed point is called Gaussian if it corresponds to a free theory. Its critical exponents agree with the canonical mass dimensions of the corresponding operators which usually amounts to the trivial fixed point values for all essential couplings . Thus standard perturbation theory is applicable only in the vicinity of a Gaussian fixed point. In this regard asymptotic safety at the Gaussian fixed point is equivalent to perturbative renormalizability plus asymptotic freedom. Due to the arguments presented in the introductory sections, however, this possibility is ruled out for gravity.

In contrast, a nontrivial fixed point, that is, a fixed point whose critical exponents differ from the canonical ones, is referred to as non-Gaussian. Usually this requires for at least one essential . It is such a non-Gaussian fixed point that provides a possible scenario for quantum gravity. As yet, studies on this subject thus mainly focused on establishing its existence.

Quantum Einstein gravity (QEG)

Quantum Einstein gravity (QEG) is the generic name for any quantum field theory of gravity that (regardless of its bare action) takes the spacetime metric as the dynamical field variable and whose symmetry is given by diffeomorphism invariance. This fixes the theory space and an RG flow of the effective average action defined over it, but it does not single out a priori any specific action functional. However, the flow equation determines a vector field on that theory space which can be investigated. If it displays a non-Gaussian fixed point by means of which the UV limit can be taken in the "asymptotically safe" way, this point acquires the status of the bare action.

Quantum quadratic gravity (QQG)

A specific realisation of QEG is quantum quadratic gravity (QQG). This a quantum extension of general relativity obtained by adding all local quadratic-in-curvature terms to the Einstein-Hilbert Lagrangian.[17][18] QQG, besides being renormalizable, has also been shown to feature a UV fixed point[19] (even in the presence of realistic matter sectors).[20] It can, therefore, be regarded as a concrete realisation of asymptotic safety.

Implementation via the effective average action

Exact functional renormalization group equation

The primary tool for investigating the gravitational RG flow with respect to the energy scale at the nonperturbative level is the effective average action for gravity.[14] It is the scale dependent version of the effective action where in the underlying functional integral field modes with covariant momenta below are suppressed while only the remaining are integrated out. For a given theory space, let and denote the set of dynamical and background fields, respectively. Then satisfies the following Wetterich–Morris-type functional RG equation (FRGE):[10][11]

Here is the second functional derivative of with respect to the quantum fields at fixed . The mode suppression operator provides a -dependent mass-term for fluctuations with covariant momenta and vanishes for . Its appearance in the numerator and denominator renders the supertrace both infrared and UV finite, peaking at momenta . The FRGE is an exact equation without any perturbative approximations. Given an initial condition it determines for all scales uniquely.

The solutions of the FRGE interpolate between the bare (microscopic) action at and the effective action at . They can be visualized as trajectories in the underlying theory space. Note that the FRGE itself is independent of the bare action. In the case of an asymptotically safe theory, the bare action is determined by the fixed point functional .

Truncations of the theory space

Let us assume there is a set of basis functionals spanning the theory space under consideration so that any action functional, i.e. any point of this theory space, can be written as a linear combination of the 's. Then solutions of the FRGE have expansions of the form

Inserting this expansion into the FRGE and expanding the trace on its right-hand side in order to extract the beta-functions, one obtains the exact RG equation in component form: . Together with the corresponding initial conditions these equations fix the evolution of the running couplings , and thus determine completely. As one can see, the FRGE gives rise to a system of infinitely many coupled differential equations since there are infinitely many couplings, and the -functions can depend on all of them. This makes it very hard to solve the system in general.

A possible way out is to restrict the analysis on a finite-dimensional subspace as an approximation of the full theory space. In other words, such a truncation of the theory space sets all but a finite number of couplings to zero, considering only the reduced basis with . This amounts to the ansatz

leading to a system of finitely many coupled differential equations, , which can now be solved employing analytical or numerical techniques.

Clearly a truncation should be chosen such that it incorporates as many features of the exact flow as possible. Although it is an approximation, the truncated flow still exhibits the nonperturbative character of the FRGE, and the -functions can contain contributions from all powers of the couplings.

Evidence from truncated flow equations

Einstein–Hilbert truncation

As described in the previous section, the FRGE lends itself to a systematic construction of nonperturbative approximations to the gravitational beta-functions by projecting the exact RG flow onto subspaces spanned by a suitable ansatz for . In its simplest form, such an ansatz is given by the Einstein–Hilbert action where Newton's constant and the cosmological constant depend on the RG scale . Let and denote the dynamical and the background metric, respectively. Then reads, for arbitrary spacetime dimension ,

Here is the scalar curvature constructed from the metric . Furthermore, denotes the gauge fixing action, and the ghost action with the ghost fields and .

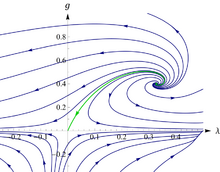

The corresponding -functions, describing the evolution of the dimensionless Newton constant and the dimensionless cosmological constant , have been derived for the first time in reference[14] for any value of the spacetime dimensionality, including the cases of below and above dimensions. In particular, in dimensions they give rise to the RG flow diagram shown on the left-hand side. The most important result is the existence of a non-Gaussian fixed point suitable for asymptotic safety. It is UV-attractive both in - and in -direction.

This fixed point is related to the one found in dimensions by perturbative methods in the sense that it is recovered in the nonperturbative approach presented here by inserting into the -functions and expanding in powers of .[14] Since the -functions were shown to exist and explicitly computed for any real, i.e., not necessarily integer value of , no analytic continuation is involved here. The fixed point in dimensions, too, is a direct result of the nonperturbative flow equations, and, in contrast to the earlier attempts, no extrapolation in is required.

Extended truncations

Subsequently, the existence of the fixed point found within the Einstein–Hilbert truncation has been confirmed in subspaces of successively increasing complexity. The next step in this development was the inclusion of an -term in the truncation ansatz.[22] This has been extended further by taking into account polynomials of the scalar curvature (so-called -truncations),[23] and the square of the Weyl curvature tensor.[24][25] Also, f(R) theories have been investigated in the Local Potential Approximation finding nonperturbative fixed points in support of the Asymptotic Safety scenario, leading to the so-called Benedetti–Caravelli (BC) fixed point. In such BC formulation, the differential equation for the Ricci scalar R is overconstrained, but some of these constraints can be removed via the resolution of movable singularities.[26][27]

Moreover, the impact of various kinds of matter fields has been investigated.[15] Also computations based on a field reparametrization invariant effective average action seem to recover the crucial fixed point.[28] In combination these results constitute strong evidence that gravity in four dimensions is a nonperturbatively renormalizable quantum field theory, indeed with a UV critical surface of reduced dimensionality, coordinatized by only a few relevant couplings.[16]

Microscopic structure of spacetime

Results of asymptotic safety related investigations indicate that the effective spacetimes of QEG have fractal-like properties on microscopic scales. It is possible to determine, for instance, their spectral dimension and argue that they undergo a dimensional reduction from 4 dimensions at macroscopic distances to 2 dimensions microscopically.[29][30] In this context it might be possible to draw the connection to other approaches to quantum gravity, e.g. to causal dynamical triangulations, and compare the results.[31]

Physics applications

Phenomenological consequences of the asymptotic safety scenario have been investigated in many areas of gravitational physics. As an example, asymptotic safety in combination with the Standard Model allows a statement about the mass of the Higgs boson and the value of the fine-structure constant.[32] Furthermore, it provides possible explanations for particular phenomena in cosmology and astrophysics, concerning black holes or inflation, for instance.[32] These different studies take advantage of the possibility that the requirement of asymptotic safety can give rise to new predictions and conclusions for the models considered, often without depending on additional, possibly unobserved, assumptions.

Criticism

Some researchers argued that the current implementations of the asymptotic safety program for gravity have unphysical features, such as the running of the Newton constant[33] or a failure to respect BRST invariance.[34] Others argued that the very concept of asymptotic safety is a misnomer, as it suggests a novel feature compared to the Wilsonian RG paradigm, while there is none (at least in the quantum field theory context, where this term is also used).[35]

See also

- Asymptotic freedom

- Causal dynamical triangulation

- Causal sets

- Critical phenomena

- Euclidean quantum gravity

- Fractal cosmology

- Functional renormalization group

- Loop quantum gravity

- Perturbative renormalization

- Planck scale

- Physics applications of asymptotically safe gravity

- Regge Calculus

- Quantum gravity

- Renormalization group

- Ultraviolet fixed point

References

- ↑ 't Hooft, Gerard; Veltman, Martinus J. G. (1974). "One-loop divergences in the theory of gravitation". Annales de l'Institut Henri Poincaré 20 (1): 69–94. Bibcode: 1974AIHPA..20...69T.

- ↑ Goroff, Marc H.; Sagnotti, Augusto (1986). "The ultraviolet behavior of Einstein gravity". Nuclear Physics 266 (3–4): 709–736. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(86)90193-8. Bibcode: 1986NuPhB.266..709G.

- ↑ Weinberg, Steven (1978). "Critical Phenomena for Field Theorists". in Zichichi, Antonino. Understanding the Fundamental Constituents of Matter. The Subnuclear Series. 14. pp. 1–52. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-0931-4_1. ISBN 978-1-4684-0931-4.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Weinberg, Steven (1979). "Ultraviolet divergences in quantum theories of gravitation". General Relativity: An Einstein centenary survey. Cambridge University Press. pp. 790–831.

- ↑ Hamber, H. W. (2009). Quantum Gravitation - The Feynman Path Integral Approach. Springer Publishing. ISBN 978-3-540-85292-6.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Wilson, Kenneth G.; Kogut, John B. (1974). "The renormalization group and the ε expansion". Physics Reports 12 (2): 75–199. doi:10.1016/0370-1573(74)90023-4. Bibcode: 1974PhR....12...75W.

- ↑ Parisi, Giorgio (1977). "On Non-Renormalizable Interactions". New Developments in Quantum Field Theory and Statistical Mechanics Cargèse 1976. pp. 281–305. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-8918-1_12. ISBN 978-1-4615-8920-4.

- ↑ Brezin, Eduard; Zinn-Justin, Jean (1976). "Renormalization of the nonlinear sigma model in 2 + epsilon dimensions". Physical Review Letters 36 (13): 691–693. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.36.691. Bibcode: 1976PhRvL..36..691B.

- ↑ Gawędzki, Krzysztof; Kupiainen, Antti (1985). "Renormalizing the nonrenormalizable". Physical Review Letters 55 (4): 363–365. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.55.363. PMID 10032331. Bibcode: 1985PhRvL..55..363G.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Wetterich, Christof (1993). "Exact evolution equation for the effective potential". Phys. Lett.. B 301 (1): 90–94. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(93)90726-X. Bibcode: 1993PhLB..301...90W.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Morris, Tim R. (1994-06-10). "The exact renormalization group and approximate solutions". International Journal of Modern Physics A 09 (14): 2411–2449. doi:10.1142/S0217751X94000972. ISSN 0217-751X. Bibcode: 1994IJMPA...9.2411M.

- ↑ Reuter, Martin; Wetterich, Christof (1994). "Effective average action for gauge theories and exact evolution equations". Nuclear Physics B 417 (1–2): 181–214. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(94)90543-6. Bibcode: 1994NuPhB.417..181R. https://bib-pubdb1.desy.de/search?p=id:%22PUBDB-2023-00426%22.

- ↑ See e.g. the review article by Berges, Tetradis and Wetterich (2002) in Further reading.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Reuter, Martin (1998). "Nonperturbative evolution equation for quantum gravity". Phys. Rev.. D 57 (2): 971–985. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.57.971. Bibcode: 1998PhRvD..57..971R.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Dou, Djamel; Percacci, Roberto (1998). "The running gravitational couplings". Classical and Quantum Gravity 15 (11): 3449–3468. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/15/11/011. Bibcode: 1998CQGra..15.3449D.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 For reviews on asymptotic safety and QEG with comprehensive lists of references see Further reading.

- ↑ Salvio, Alberto (2018). "Quadratic Gravity". Frontiers in Physics 6 (77). doi:10.3389/fphy.2018.00077. Bibcode: 2018FrP.....6...77S.

- ↑ Salvio, Alberto (2021). "Dimensional Transmutation in Gravity and Cosmology". Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 36 (8n09, 2130006): 2130006–2130831. doi:10.1142/S0217751X21300064. Bibcode: 2021IJMPA..3630006S.

- ↑ Falls, Kevin; Ohta, Nobuyoshi; Percacci, Roberto (2020). "Towards the determination of the dimension of the critical surface in asymptotically safe gravity". Physics Letters B 810 (135773). doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2020.135773. Bibcode: 2020PhLB..81035773F.

- ↑ Salvio, Alberto; Strumia, Alessandro (2018). "A gravity up to Infinite Energies". European Physical Journal C 78 (2,124): 124. doi:10.1140/epjc/s10052-018-5588-4. PMID 31258400. Bibcode: 2018EPJC...78..124S.

- ↑ Reuter, Martin; Saueressig, Frank (2002). "Renormalization group flow of quantum gravity in the Einstein-Hilbert truncation". Phys. Rev.. D 65 (6). doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.65.065016. Bibcode: 2002PhRvD..65f5016R.

- ↑ Lauscher, Oliver; Reuter, Martin (2002). "Flow equation of quantum Einstein gravity in a higher-derivative truncation". Physical Review D 66 (2). doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.66.025026. Bibcode: 2002PhRvD..66b5026L.

- ↑ Codello, Alessandro; Percacci, Roberto; Rahmede, Christoph (2008). "Ultraviolet properties of f(R)-gravity". International Journal of Modern Physics A 23 (1): 143–150. doi:10.1142/S0217751X08038135. Bibcode: 2008IJMPA..23..143C.

- ↑ Benedetti, Dario; Machado, Pedro F.; Saueressig, Frank (2009). "Asymptotic safety in higher-derivative gravity". Modern Physics Letters A 24 (28): 2233–2241. doi:10.1142/S0217732309031521. Bibcode: 2009MPLA...24.2233B.

- ↑ The contact to perturbation theory is established in: Niedermaier, Max (2009). "Gravitational Fixed Points from Perturbation Theory". Physical Review Letters 103 (10). doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.101303. PMID 19792294. Bibcode: 2009PhRvL.103j1303N.

- ↑ The LPA approximation has been first investigated in Quantum Gravity in: Benedetti, Dario; Caravelli, Francesco (2012). "The local potential approximation in quantum gravity". JHEP 17 (6): 1–30. doi:10.1007/JHEP06(2012)017. Bibcode: 2012JHEP...06..017B.

- ↑ See also Morris, Stulga, The functional f(R) approximation, arXiv:2210.11356 (2022)

- ↑ Donkin, Ivan; Pawlowski, Jan M. (2012). "The phase diagram of quantum gravity from diffeomorphism-invariant RG-flows". arXiv:1203.4207 [hep-th].

- ↑ Lauscher, Oliver; Reuter, Martin (2001). "Ultraviolet fixed point and generalized flow equation of quantum gravity". Physical Review D 65 (2). doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.65.025013. Bibcode: 2001PhRvD..65b5013L.

- ↑ Lauscher, Oliver; Reuter, Martin (2005). "Fractal spacetime structure in asymptotically safe gravity". Journal of High Energy Physics 2005 (10): 050. doi:10.1088/1126-6708/2005/10/050. Bibcode: 2005JHEP...10..050L.

- ↑ For a review see Further reading: Reuter; Saueressig (2012)

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 See main article Physics applications of asymptotically safe gravity and references therein.

- ↑ Donoghue, John F. (2020-03-11). "A Critique of the Asymptotic Safety Program". Frontiers in Physics 8. doi:10.3389/fphy.2020.00056. ISSN 2296-424X. Bibcode: 2020FrP.....8...56D.

- ↑ Distler, Jacques (2015-06-19). "Asymptotic safety and the Gribov ambiguity". https://golem.ph.utexas.edu/~distler/blog/archives/002833.html.

- ↑ Asrat, Meseret (2018). "Comments on asymptotic safety in four-dimensional N=1 supersymmetric gauge theories". arXiv:1805.11543 [hep-th].

Further reading

- Niedermaier, Max; Reuter, Martin (2006). "The Asymptotic Safety Scenario in Quantum Gravity". Living Rev. Relativ. 9 (1): 5. doi:10.12942/lrr-2006-5. PMID 28179875. Bibcode: 2006LRR.....9....5N.

- Percacci, Roberto (2009). "Approaches to Quantum Gravity: Towards a New Understanding of Space, Time and Matter". in Oriti, D.. Cambridge University Press. Bibcode: 2007arXiv0709.3851P.

- Berges, Jürgen; Tetradis, Nikolaos; Wetterich, Christof (2002). "Non-perturbative renormalization flow in quantum field theory and statistical physics". Physics Reports 363 (4–6): 223–386. doi:10.1016/S0370-1573(01)00098-9. Bibcode: 2002PhR...363..223B.

- Reuter, Martin; Saueressig, Frank (2012). "Quantum Einstein Gravity". New J. Phys. 14 (5). doi:10.1088/1367-2630/14/5/055022. Bibcode: 2012NJPh...14e5022R.

- Bonanno, Alfio; Saueressig, Frank (2017). "Asymptotically safe cosmology – a status report". Comptes Rendus Physique 18 (3–4): 254. doi:10.1016/j.crhy.2017.02.002. Bibcode: 2017CRPhy..18..254B.

- Litim, Daniel (2011). "Renormalisation group and the Planck scale". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 69 (1946): 2759–2778. doi:10.1098/rsta.2011.0103. PMID 21646277. Bibcode: 2011RSPTA.369.2759L.

- Nagy, Sandor (2012). "Lectures on renormalization and asymptotic safety". Annals of Physics 350: 310–346. doi:10.1016/j.aop.2014.07.027. Bibcode: 2014AnPhy.350..310N.

External links

- The Asymptotic Safety FAQs – A collection of questions and answers about asymptotic safety and a comprehensive list of references.

- Asymptotic Safety in quantum gravity – A Scholarpedia article about the same topic with some more details on the gravitational effective average action.

- The Quantum Theory of Fields: Effective or Fundamental? – A talk by Steven Weinberg at CERN on July 7, 2009.

- Asymptotic Safety - 30 Years Later – All talks of the workshop held at the Perimeter Institute on November 5 – 8, 2009.

- Four radical routes to a theory of everything – An article by Amanda Gefter on quantum gravity, published 2008 in New Scientist (Physics & Math).

- "Weinberg "Living with infinities" - Källén Lecture 2009". Andrea Idini. January 14, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rFd9PIy_zXs. (From 1:11:28 to 1:18:10 in the video, Weinberg gives a brief discussion of asymptotic safety. Also see Weinberg's answer to Cecilia Jarlskog's question at the end of the lecture. The 2009 Källén lecture was recorded on February 13, 2009.)

|

KSF

KSF