Classical electromagnetism

Topic: Physics

From HandWiki - Reading time: 8 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 8 min

| Part of a series of articles about |

| Electromagnetism |

|---|

|

Classical electromagnetism or classical electrodynamics is a branch of theoretical physics that studies the interactions between electric charges and currents using an extension of the classical Newtonian model. It is, therefore, a classical field theory. The theory provides a description of electromagnetic phenomena whenever the relevant length scales and field strengths are large enough that quantum mechanical effects are negligible. For small distances and low field strengths, such interactions are better described by quantum electrodynamics which is a quantum field theory.

Fundamental physical aspects of classical electrodynamics are presented in many textbooks. For the undergraduate level, textbooks like The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Electricity and Magnetism, and Introduction to Electrodynamics are considered as classic references and for the graduate level, textbooks like Classical Electricity and Magnetism,[1] Classical Electrodynamics, and Course of Theoretical Physics are considered as classic references.

History

The physical phenomena that electromagnetism describes have been studied as separate fields since antiquity. For example, there were many advances in the field of optics centuries before light was understood to be an electromagnetic wave. However, the theory of electromagnetism, as it is currently understood, grew out of Michael Faraday's experiments suggesting the existence of an electromagnetic field and James Clerk Maxwell's use of differential equations to describe it in his A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism (1873). The development of electromagnetism in Europe included the development of methods to measure voltage, current, capacitance, and resistance. Detailed historical accounts are given by Wolfgang Pauli,[2] E. T. Whittaker,[3] Abraham Pais,[4] and Bruce J. Hunt.[5]

Lorentz force

The electromagnetic field exerts the following force (often called the Lorentz force) on charged particles:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{F} = q\mathbf{E} + q\mathbf{v} \times \mathbf{B} }[/math]

where all boldfaced quantities are vectors: F is the force that a particle with charge q experiences, E is the electric field at the location of the particle, v is the velocity of the particle, B is the magnetic field at the location of the particle.

The above equation illustrates that the Lorentz force is the sum of two vectors. One is the cross product of the velocity and magnetic field vectors. Based on the properties of the cross product, this produces a vector that is perpendicular to both the velocity and magnetic field vectors. The other vector is in the same direction as the electric field. The sum of these two vectors is the Lorentz force.

Although the equation appears to suggest that the electric and magnetic fields are independent, the equation can be rewritten in term of four-current (instead of charge) and a single electromagnetic tensor that represents the combined field ([math]\displaystyle{ F^{\mu \nu} }[/math]):

- [math]\displaystyle{ f_{\alpha} = F_{\alpha\beta}J^{\beta} .\! }[/math]

Electric field

The electric field E is defined such that, on a stationary charge:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{F} = q_0 \mathbf{E} }[/math]

where q0 is what is known as a test charge and F is the force on that charge. The size of the charge does not really matter, as long as it is small enough not to influence the electric field by its mere presence. What is plain from this definition, though, is that the unit of E is N/C (newtons per coulomb). This unit is equal to V/m (volts per meter); see below.

In electrostatics, where charges are not moving, around a distribution of point charges, the forces determined from Coulomb's law may be summed. The result after dividing by q0 is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E(r)} = \frac{1}{4 \pi \varepsilon_0 } \sum_{i=1}^{n} \frac{q_i \left( \mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r}_i \right)} {\left| \mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r}_i \right|^3} }[/math]

where n is the number of charges, qi is the amount of charge associated with the ith charge, ri is the position of the ith charge, r is the position where the electric field is being determined, and ε0 is the electric constant.

If the field is instead produced by a continuous distribution of charge, the summation becomes an integral:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E(r)} = \frac{1}{ 4 \pi \varepsilon_0 } \int \frac{\rho(\mathbf{r'}) \left( \mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r'} \right)} {\left| \mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r'} \right|^3} \mathrm{d^3}\mathbf{r'} }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \rho(\mathbf{r'}) }[/math] is the charge density and [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{r}-\mathbf{r'} }[/math] is the vector that points from the volume element [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{d^3}\mathbf{r'} }[/math] to the point in space where E is being determined.

Both of the above equations are cumbersome, especially if one wants to determine E as a function of position. A scalar function called the electric potential can help. Electric potential, also called voltage (the units for which are the volt), is defined by the line integral

- [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi \mathbf{(r)} = - \int_C \mathbf{E} \cdot \mathrm{d}\mathbf{l} }[/math]

where φ(r) is the electric potential, and C is the path over which the integral is being taken.

Unfortunately, this definition has a caveat. From Maxwell's equations, it is clear that ∇ × E is not always zero, and hence the scalar potential alone is insufficient to define the electric field exactly. As a result, one must add a correction factor, which is generally done by subtracting the time derivative of the A vector potential described below. Whenever the charges are quasistatic, however, this condition will be essentially met.

From the definition of charge, one can easily show that the electric potential of a point charge as a function of position is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi \mathbf{(r)} = \frac{1}{4 \pi \varepsilon_0 } \sum_{i=1}^{n} \frac{q_i} {\left| \mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r}_i \right|} }[/math]

where q is the point charge's charge, r is the position at which the potential is being determined, and ri is the position of each point charge. The potential for a continuous distribution of charge is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi \mathbf{(r)} = \frac{1}{4 \pi \varepsilon_0} \int \frac{\rho(\mathbf{r'})}{|\mathbf{r}-\mathbf{r'}|}\, \mathrm{d^3}\mathbf{r'} }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \rho(\mathbf{r'}) }[/math] is the charge density, and [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{r}-\mathbf{r'} }[/math] is the distance from the volume element [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{d^3}\mathbf{r'} }[/math] to point in space where φ is being determined.

The scalar φ will add to other potentials as a scalar. This makes it relatively easy to break complex problems down into simple parts and add their potentials. Taking the definition of φ backwards, we see that the electric field is just the negative gradient (the del operator) of the potential. Or:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E(r)} = -\nabla \varphi \mathbf{(r)} . }[/math]

From this formula it is clear that E can be expressed in V/m (volts per meter).

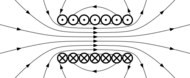

Electromagnetic waves

A changing electromagnetic field propagates away from its origin in the form of a wave. These waves travel in vacuum at the speed of light and exist in a wide spectrum of wavelengths. Examples of the dynamic fields of electromagnetic radiation (in order of increasing frequency): radio waves, microwaves, light (infrared, visible light and ultraviolet), x-rays and gamma rays. In the field of particle physics this electromagnetic radiation is the manifestation of the electromagnetic interaction between charged particles.

General field equations

As simple and satisfying as Coulomb's equation may be, it is not entirely correct in the context of classical electromagnetism. Problems arise because changes in charge distributions require a non-zero amount of time to be "felt" elsewhere (required by special relativity).

For the fields of general charge distributions, the retarded potentials can be computed and differentiated accordingly to yield Jefimenko's equations.

Retarded potentials can also be derived for point charges, and the equations are known as the Liénard–Wiechert potentials. The scalar potential is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi = \frac{1}{4 \pi \varepsilon_0} \frac{q}{\left| \mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r}_q(t_{\rm ret}) \right|-\frac{\mathbf{v}_q(t_{\rm ret})}{c} \cdot (\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r}_q(t_{\rm ret}))} }[/math]

where q is the point charge's charge and r is the position. rq and vq are the position and velocity of the charge, respectively, as a function of retarded time. The vector potential is similar:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{A} = \frac{\mu_0}{4 \pi} \frac{q\mathbf{v}_q(t_{\rm ret})}{\left| \mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r}_q(t_{\rm ret}) \right|-\frac{\mathbf{v}_q(t_{\rm ret})}{c} \cdot (\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r}_q(t_{\rm ret}))}. }[/math]

These can then be differentiated accordingly to obtain the complete field equations for a moving point particle.

Models

Branches of classical electromagnetism such as optics, electrical and electronic engineering consist of a collection of relevant mathematical models of different degrees of simplification and idealization to enhance the understanding of specific electrodynamics phenomena.[6] An electrodynamics phenomenon is determined by the particular fields, specific densities of electric charges and currents, and the particular transmission medium. Since there are infinitely many of them, in modeling there is a need for some typical, representative

- (a) electrical charges and currents, e.g. moving pointlike charges and electric and magnetic dipoles, electric currents in a conductor etc.;

- (b) electromagnetic fields, e.g. voltages, the Liénard–Wiechert potentials, the monochromatic plane waves, optical rays; radio waves, microwaves, infrared radiation, visible light, ultraviolet radiation, X-rays, gamma rays etc.;

- (c) transmission media, e.g. electronic components, antennas, electromagnetic waveguides, flat mirrors, mirrors with curved surfaces convex lenses, concave lenses; resistors, inductors, capacitors, switches; wires, electric and optical cables, transmission lines, integrated circuits etc.; all of which have only few variable characteristics.

See also

- List of textbooks in electromagnetism

- Leontovich boundary condition

- Weber electrodynamics

- Wheeler–Feynman absorber theory

References

- ↑ Panofsky, W. K. H.; Phillips, M. (2005). Classical Electricity and Magnetism. Dover. ISBN 9780486439242. https://store.doverpublications.com/0486439240.html.

- ↑ Pauli, W., 1958, Theory of Relativity, Pergamon, London

- ↑ Whittaker, E. T., 1960, History of the Theories of the Aether and Electricity, Harper Torchbooks, New York.

- ↑ Pais, A., 1983, Subtle is the Lord: The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein, Oxford University Press, Oxford

- ↑ Bruce J. Hunt (1991) The Maxwellians

- ↑ Peierls, Rudolf. Model-making in physics, Contemporary Physics, Volume 21 (1), January 1980, 3-17.

|

KSF

KSF