Table of Contents

- 1 Overview

- 2 Historical background

- 3 Ideal gas law

- 4 Cubic equations of state

- 5 Virial equations of state

- 6 Physically based equations of state

- 7 Multiparameter equations of state

- 8 List of further equations of state

- 9 See also

- 10 References

- 11 External links Categories

- History

- Culture

- Art

- Education

- , number of moles of a substance

- , , molar volume, the volume of 1 mole of gas or liquid

- , ideal gas constant ≈ 8.3144621 J/mol·K

- , pressure at the critical point

- , molar volume at the critical point

- , absolute temperature at the critical point

- is pressure

- is molar density

- Tait equation for water and other liquids. Several equations are referred to as the Tait equation.

- Murnaghan equation of state

- Birch–Murnaghan equation of state

- Stacey–Brennan–Irvine equation of state[42]

- Modified Rydberg equation of state[43][44][45]

- Adapted polynomial equation of state[46]

- Johnson–Holmquist equation of state

- Mie–Grüneisen equation of state[47][48]

- Anton-Schmidt equation of state

- State-transition equation

- ↑ Perrot, Pierre (1998). A to Z of Thermodynamics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-856552-9.

- ↑ Eliezer, S.; Gahatak, A.; Hora, H. (1986). An Introduction to Equation of State: Theory and Applications. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521303893.

- ↑ Horedt, G.P. (2004). Polytropes. Applications in Astrophysics and Related Fields. Dordrecht: Kluwer. ISBN 1-4020-2350-2.

- ↑ Kontogeorgis, Georgios M.; Liang, Xiaodong; Arya, Alay; Tsivintzelis, Ioannis (May 2020). "Equations of state in three centuries. Are we closer to arriving to a single model for all applications?". Chemical Engineering Science: X 7. doi:10.1016/j.cesx.2020.100060.

- ↑ Kontogeorgis, Georgios M.; Liang, Xiaodong; Arya, Alay; Tsivintzelis, Ioannis (May 2020). "Equations of state in three centuries. Are we closer to arriving to a single model for all applications?". Chemical Engineering Science: X 7. doi:10.1016/j.cesx.2020.100060.

- ↑ van der Waals; J. D. (1873). On the Continuity of the Gaseous and Liquid States (doctoral dissertation). Universiteit Leiden.

- ↑ Redlich, Otto.; Kwong, J. N. S. (1949-02-01). "On the Thermodynamics of Solutions. V. An Equation of State. Fugacities of Gaseous Solutions.". Chemical Reviews 44 (1): 233–244. doi:10.1021/cr60137a013. ISSN 0009-2665. PMID 18125401.

- ↑ Soave, Giorgio (1972). "Equilibrium constants from a modified Redlich-Kwong equation of state". Chemical Engineering Science 27 (6): 1197–1203. doi:10.1016/0009-2509(72)80096-4. Bibcode: 1972ChEnS..27.1197S.

- ↑ Landau, L. D., Lifshitz, E. M. (1980). Statistical physics: Part I (Vol. 5). page 162-166.

- ↑ K.E. Starling (1973). Fluid Properties for Light Petroleum Systems. Gulf Publishing Company. ISBN 087201293X. OCLC 947455.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Stephan, Simon; Staubach, Jens; Hasse, Hans (November 2020). "Review and comparison of equations of state for the Lennard-Jones fluid" (in en). Fluid Phase Equilibria 523. doi:10.1016/j.fluid.2020.112772. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0378381220303204.

- ↑ Nicolas, J.J.; Gubbins, K.E.; Streett, W.B.; Tildesley, D.J. (May 1979). "Equation of state for the Lennard-Jones fluid" (in en). Molecular Physics 37 (5): 1429–1454. doi:10.1080/00268977900101051. ISSN 0026-8976. Bibcode: 1979MolPh..37.1429N. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00268977900101051.

- ↑ Starling, Kenneth E. (1973). Fluid Properties for Light Petroleum Systems. Gulf Publishing Company. p. 270.

- ↑ Lee, Byung Ik; Kesler, Michael G. (1975). "A generalized thermodynamic correlation based on three-parameter corresponding states" (in fr). AIChE Journal 21 (3): 510–527. doi:10.1002/aic.690210313. ISSN 1547-5905. Bibcode: 1975AIChE..21..510L.

- ↑ Kontogeorgis, Georgios M.; Michelsen, Michael L.; Folas, Georgios K.; Derawi, Samer; von Solms, Nicolas; Stenby, Erling H. (2006-07-01). "Ten Years with the CPA (Cubic-Plus-Association) Equation of State. Part 1. Pure Compounds and Self-Associating Systems" (in en). Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 45 (14): 4855–4868. doi:10.1021/ie051305v. ISSN 0888-5885. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/ie051305v.

- ↑ Kontogeorgis, Georgios M.; Voutsas, Epaminondas C.; Yakoumis, Iakovos V.; Tassios, Dimitrios P. (1996-01-01). "An Equation of State for Associating Fluids" (in en). Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 35 (11): 4310–4318. doi:10.1021/ie9600203. ISSN 0888-5885. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/ie9600203.

- ↑ Cotterman, R. L.; Prausnitz, J. M. (November 1986). "Molecular thermodynamics for fluids at low and high densities. Part II: Phase equilibria for mixtures containing components with large differences in molecular size or potential energy" (in en). AIChE Journal 32 (11): 1799–1812. doi:10.1002/aic.690321105. ISSN 0001-1541. Bibcode: 1986AIChE..32.1799C. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/aic.690321105.

- ↑ Weingerl, Ulrike; Wendland, Martin; Fischer, Johann; Müller, Andreas; Winkelmann, Jochen (March 2001). "Backone family of equations of state: 2. Nonpolar and polar fluid mixtures" (in en). AIChE Journal 47 (3): 705–717. doi:10.1002/aic.690470317. Bibcode: 2001AIChE..47..705W. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/aic.690470317.

- ↑ Müller, Andreas; Winkelmann, Jochen; Fischer, Johann (April 1996). "Backone family of equations of state: 1. Nonpolar and polar pure fluids" (in en). AIChE Journal 42 (4): 1116–1126. doi:10.1002/aic.690420423. ISSN 0001-1541. Bibcode: 1996AIChE..42.1116M. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/aic.690420423.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Chapman, Walter G.; Gubbins, K.E.; Jackson, G.; Radosz, M. (1 December 1989). "SAFT: Equation-of-state solution model for associating fluids" (in en). Fluid Phase Equilibria 52: 31–38. doi:10.1016/0378-3812(89)80308-5. ISSN 0378-3812.

- ↑ Gross, Joachim; Sadowski, Gabriele (2002). "Application of the Perturbed-Chain SAFT Equation of State to Associating Systems". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 41 (22): 5510–5515. doi:10.1021/ie010954d.

- ↑ Saajanlehto, Meri; Uusi-Kyyny, Petri; Alopaeus, Ville (2014). "A modified continuous flow apparatus for gas solubility measurements at high pressure and temperature with camera system". Fluid Phase Equilibria 382: 150–157. doi:10.1016/j.fluid.2014.08.035.

- ↑ Betancourt-Cárdenas, F.F.; Galicia-Luna, L.A.; Sandler, S.I. (March 2008). "Equation of state for the Lennard–Jones fluid based on the perturbation theory" (in en). Fluid Phase Equilibria 264 (1–2): 174–183. doi:10.1016/j.fluid.2007.11.015. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0378381207007030.

- ↑ Levesque, Dominique; Verlet, Loup (1969-06-05). "Perturbation Theory and Equation of State for Fluids" (in en). Physical Review 182 (1): 307–316. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.182.307. ISSN 0031-899X. Bibcode: 1969PhRv..182..307L. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRev.182.307.

- ↑ Lenhard, Johannes; Stephan, Simon; Hasse, Hans (February 2024). "A child of prediction. On the History, Ontology, and Computation of the Lennard-Jonesium" (in en). Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 103: 105–113. doi:10.1016/j.shpsa.2023.11.007. PMID 38128443. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0039368123001668.

- ↑ Barker, J. A.; Henderson, D. (December 1967). "Perturbation Theory and Equation of State for Fluids. II. A Successful Theory of Liquids" (in en). The Journal of Chemical Physics 47 (11): 4714–4721. doi:10.1063/1.1701689. ISSN 0021-9606. Bibcode: 1967JChPh..47.4714B. http://aip.scitation.org/doi/10.1063/1.1701689.

- ↑ Weeks, John D.; Chandler, David; Andersen, Hans C. (1971-06-15). "Role of Repulsive Forces in Determining the Equilibrium Structure of Simple Liquids" (in en). The Journal of Chemical Physics 54 (12): 5237–5247. doi:10.1063/1.1674820. ISSN 0021-9606. Bibcode: 1971JChPh..54.5237W. http://aip.scitation.org/doi/10.1063/1.1674820.

- ↑ Wertheim, M. S. (April 1984). "Fluids with highly directional attractive forces. I. Statistical thermodynamics". Journal of Statistical Physics 35 (1–2): 19–34. doi:10.1007/bf01017362. ISSN 0022-4715. Bibcode: 1984JSP....35...19W. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/bf01017362.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Chapman, Walter G. (1988). "Theory and Simulation of Associating Liquid Mixtures" (in en). Doctoral Dissertation, Cornell University.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Chapman, Walter G.; Jackson, G.; Gubbins, K.E. (11 July 1988). "Phase equilibria of associating fluids: Chain molecules with multiple bonding sites" (in en). Molecular Physics 65: 1057–1079. doi:10.1080/00268978800101601.

- ↑ Chapman, Walter G.; Gubbins, K.E.; Jackson, G.; Radosz, M. (1 August 1990). "New Reference Equation of State for Associating Liquids" (in en). Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 29 (8): 1709–1721. doi:10.1021/ie00104a021.

- ↑ Gil-Villegas, Alejandro; Galindo, Amparo; Whitehead, Paul J.; Mills, Stuart J.; Jackson, George; Burgess, Andrew N. (1997). "Statistical associating fluid theory for chain molecules with attractive potentials of variable range". The Journal of Chemical Physics 106 (10): 4168–4186. doi:10.1063/1.473101. Bibcode: 1997JChPh.106.4168G.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Span, R.; Wagner, W. (2003). "Equations of State for Technical Applications. I. Simultaneously Optimized Functional Forms for Nonpolar and Polar Fluids". International Journal of Thermophysics 24 (1): 1–39. doi:10.1023/A:1022390430888. http://link.springer.com/10.1023/A:1022390430888.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Span, Roland; Lemmon, Eric W.; Jacobsen, Richard T; Wagner, Wolfgang; Yokozeki, Akimichi (November 2000). "A Reference Equation of State for the Thermodynamic Properties of Nitrogen for Temperatures from 63.151 to 1000 K and Pressures to 2200 MPa" (in en). Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data 29 (6): 1361–1433. doi:10.1063/1.1349047. ISSN 0047-2689. Bibcode: 2000JPCRD..29.1361S. http://aip.scitation.org/doi/10.1063/1.1349047.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Wagner, W.; Pruß, A. (June 2002). "The IAPWS Formulation 1995 for the Thermodynamic Properties of Ordinary Water Substance for General and Scientific Use" (in en). Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data 31 (2): 387–535. doi:10.1063/1.1461829. ISSN 0047-2689. http://aip.scitation.org/doi/10.1063/1.1461829.

- ↑ Deiters, Ulrich K.; Bell, Ian H. (December 2020). "Unphysical Critical Curves of Binary Mixtures Predicted with GERG Models" (in en). International Journal of Thermophysics 41 (12): 169. doi:10.1007/s10765-020-02743-3. ISSN 0195-928X. PMID 34121788. Bibcode: 2020IJT....41..169D.

- ↑ Shi, Lanlan; Mao, Shide (2012-01-01). "Applications of the IAPWS-95 formulation in fluid inclusion and mineral-fluid phase equilibria" (in en). Geoscience Frontiers 3 (1): 51–58. doi:10.1016/j.gsf.2011.08.002. ISSN 1674-9871. Bibcode: 2012GeoFr...3...51S.

- ↑ Le Métayer, O; Massoni, J; Saurel, R (2004-03-01). "Élaboration des lois d'état d'un liquide et de sa vapeur pour les modèles d'écoulements diphasiques" (in fr). International Journal of Thermal Sciences 43 (3): 265–276. doi:10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2003.09.002. ISSN 1290-0729. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1290072903001443.

- ↑ Al-Raeei, Marwan (2022-04-01). "Morse oscillator equation of state: An integral equation theory based with virial expansion and compressibility terms". Heliyon 8 (4). doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09328. ISSN 2405-8440. PMID 35520603. Bibcode: 2022Heliy...809328A.

- ↑ B. M. Dobratz; P. C. Crawford (1985). "LLNL Explosives Handbook: Properties of Chemical Explosives and Explosive Simulants". Ucrl-52997. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/10012469501/. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ↑ Wilkins, Mark L. (1999), Computer Simulation of Dynamic Phenomena, Springer, p. 80, ISBN 9783662038857, https://books.google.com/books?id=b3npCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA1, retrieved 31 August 2018

- ↑ Stacey, F.D.; Brennan, B. J.; Irvine, R.D. (1981). "Finite strain theories and comparisons with seismological data". Surveys in Geophysics 4 (3): 189–232. doi:10.1007/BF01449185. Bibcode: 1981GeoSu...4..189S. https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:399907. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ↑ Holzapfel, W.B. (1991). "Equations of states and scaling rules for molecular solids under strong compression" in "Molecular systems under high pressure" ed. R. Pucci and G. Piccino. North-Holland: Elsevier. pp. 61–68.

- ↑ Holzapfel, W.B. (1991). "Equations of state for solids under strong compression". High Press. Res. 7: 290–293. doi:10.1080/08957959108245571.

- ↑ Holzapfel, Wi.B. (1996). "Physics of solids under strong compression". Rep. Prog. Phys. 59 (1): 29–90. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/59/1/002. ISSN 0034-4885. Bibcode: 1996RPPh...59...29H.

- ↑ Holzapfel, W.B. (1998). "Equation of state for solids under strong compression". High Press. Res. 16 (2): 81–126. doi:10.1080/08957959808200283. ISSN 0895-7959. Bibcode: 1998HPR....16...81H.

- ↑ Holzapfel, Wilfried B. (2004). "Equations of State and Thermophysical Properties of Solids Under Pressure". in Katrusiak, A.; McMillan, P. (in en). High-Pressure Crystallography. NATO Science Series. 140. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluver Academic. pp. 217–236. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-2102-2_14. ISBN 978-1-4020-1954-8. https://physik.uni-paderborn.de/fileadmin/physik/Alumni/Holzapfel_LOP/ldv-238.pdf. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ↑ S. Benjelloun, "Thermodynamic identities and thermodynamic consistency of Equation of States", Link to Archiv e-print Link to Hal e-print

- Boiling

- Boiling point

- Condensation

- Critical line

- Critical point

- Crystallization

- Deposition

- Evaporation

- Flash evaporation

- Freezing

- Chemical ionization

- Ionization

- Lambda point

- Melting

- Melting point

- Recombination

- Regelation

- Saturated fluid

- Sublimation

- Supercooling

- Triple point

- Vaporization

- Vitrification

Contents

Equation of state

Topic: Physics

From HandWiki - Reading time: 21 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 21 min

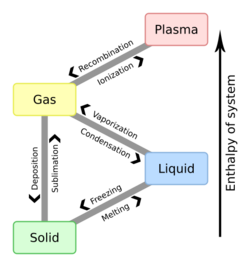

In physics and chemistry, an equation of state is a thermodynamic equation relating state variables, which describe the state of matter under a given set of physical conditions, such as pressure, volume, temperature, or internal energy.[1][2] Most modern equations of state are formulated in the Helmholtz free energy. Equations of state are useful in describing the properties of pure substances and mixtures in liquids, gases, and solid states as well as the state of matter in the interior of stars.[3] Though there are many equations of state, none accurately predicts properties of substances under all conditions. The quest for a universal equation of state has spanned three centuries.[4]

| Thermodynamics | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

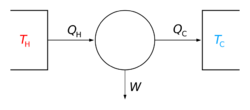

The classical Carnot heat engine | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

Overview

At present, there is no single equation of state that accurately predicts the properties of all substances under all conditions. An example of an equation of state correlates densities of gases and liquids to temperatures and pressures, known as the ideal gas law, which is roughly accurate for weakly polar gases at low pressures and moderate temperatures. This equation becomes increasingly inaccurate at higher pressures and lower temperatures, and fails to predict condensation from a gas to a liquid.

The general form of an equation of state may be written as

where is the pressure, the volume, and the temperature of the system. Yet also other variables may be used in that form. It is directly related to Gibbs phase rule, that is, the number of independent variables depends on the number of substances and phases in the system.

An equation used to model this relationship is called an equation of state. In most cases this model will comprise some empirical parameters that are usually adjusted to measurement data. Equations of state can also describe solids, including the transition of solids from one crystalline state to another. Equations of state are also used for the modeling of the state of matter in the interior of stars, including neutron stars, dense matter (quark–gluon plasmas) and radiation fields. A related concept is the perfect fluid equation of state used in cosmology.

Equations of state are applied in many fields such as process engineering and petroleum industry as well as pharmaceutical industry.

Any consistent set of units may be used, although SI units are preferred. Absolute temperature refers to the use of the Kelvin (K), with zero being absolute zero.

Historical background

Equations of state essentially began three centuries ago with the history of the ideal gas law:[5]

Boyle's law was one of the earliest formulation of an equation of state. In 1662, the Irish physicist and chemist Robert Boyle performed a series of experiments employing a J-shaped glass tube, which was sealed on one end. Mercury was added to the tube, trapping a fixed quantity of air in the short, sealed end of the tube. Then the volume of gas was measured as additional mercury was added to the tube. The pressure of the gas could be determined by the difference between the mercury level in the short end of the tube and that in the long, open end. Through these experiments, Boyle noted that the gas volume varied inversely with the pressure. In mathematical form, this can be stated as:The above relationship has also been attributed to Edme Mariotte and is sometimes referred to as Mariotte's law. However, Mariotte's work was not published until 1676.

In 1787 the French physicist Jacques Charles found that oxygen, nitrogen, hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and air expand to roughly the same extent over the same 80-kelvin interval. This is known today as Charles's law. Later, in 1802, Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac published results of similar experiments, indicating a linear relationship between volume and temperature:Dalton's law (1801) of partial pressure states that the pressure of a mixture of gases is equal to the sum of the pressures of all of the constituent gases alone.

Mathematically, this can be represented for species as:In 1834, Émile Clapeyron combined Boyle's law and Charles' law into the first statement of the ideal gas law. Initially, the law was formulated as pVm = R(TC + 267) (with temperature expressed in degrees Celsius), where R is the gas constant. However, later work revealed that the number should actually be closer to 273.2, and then the Celsius scale was defined with , giving:In 1873, J. D. van der Waals introduced the first equation of state derived by the assumption of a finite volume occupied by the constituent molecules.[6] His new formula revolutionized the study of equations of state, and was the starting point of cubic equations of state, which most famously continued via the Redlich–Kwong equation of state[7] and the Soave modification of Redlich-Kwong.[8]

The van der Waals equation of state can be written as

where is a parameter describing the attractive energy between particles and is a parameter describing the volume of the particles.

Ideal gas law

Classical ideal gas law

The classical ideal gas law may be written

In the form shown above, the equation of state is thus

If the calorically perfect gas approximation is used, then the ideal gas law may also be expressed as follows where is the number density of the gas (number of atoms/molecules per unit volume), is the (constant) adiabatic index (ratio of specific heats), is the internal energy per unit mass (the "specific internal energy"), is the specific heat capacity at constant volume, and is the specific heat capacity at constant pressure.

Quantum ideal gas law

Since for atomic and molecular gases, the classical ideal gas law is well suited in most cases, let us describe the equation of state for elementary particles with mass and spin that takes into account quantum effects. In the following, the upper sign will always correspond to Fermi–Dirac statistics and the lower sign to Bose–Einstein statistics. The equation of state of such gases with particles occupying a volume with temperature and pressure is given by[9]

where is the Boltzmann constant and the chemical potential is given by the following implicit function

In the limiting case where , this equation of state will reduce to that of the classical ideal gas. It can be shown that the above equation of state in the limit reduces to

With a fixed number density , decreasing the temperature causes in Fermi gas, an increase in the value for pressure from its classical value implying an effective repulsion between particles (this is an apparent repulsion due to quantum exchange effects not because of actual interactions between particles since in ideal gas, interactional forces are neglected) and in Bose gas, a decrease in pressure from its classical value implying an effective attraction. The quantum nature of this equation is in it dependence on s and ħ.

Cubic equations of state

Cubic equations of state are called such because they can be rewritten as a cubic function of . Cubic equations of state originated from the van der Waals equation of state. Hence, all cubic equations of state can be considered 'modified van der Waals equation of state'. There is a very large number of such cubic equations of state. For process engineering, cubic equations of state are today still highly relevant, e.g. the Peng Robinson equation of state or the Soave Redlich Kwong equation of state.

Virial equations of state

Virial equation of state

Although usually not the most convenient equation of state, the virial equation is important because it can be derived directly from statistical mechanics. This equation is also called the Kamerlingh Onnes equation. If appropriate assumptions are made about the mathematical form of intermolecular forces, theoretical expressions can be developed for each of the coefficients. A is the first virial coefficient, which has a constant value of 1 and makes the statement that when volume is large, all fluids behave like ideal gases. The second virial coefficient B corresponds to interactions between pairs of molecules, C to triplets, and so on. Accuracy can be increased indefinitely by considering higher order terms. The coefficients B, C, D, etc. are functions of temperature only.

The BWR equation of state

where

Values of the various parameters can be found in reference materials.[10] The BWR equation of state has also frequently been used for the modelling of the Lennard-Jones fluid.[11][12] There are several extensions and modifications of the classical BWR equation of state available.

The Benedict–Webb–Rubin–Starling[13] equation of state is a modified BWR equation of state and can be written as

Note that in this virial equation, the fourth and fifth virial terms are zero. The second virial coefficient is monotonically decreasing as temperature is lowered. The third virial coefficient is monotonically increasing as temperature is lowered.

The Lee–Kesler equation of state is based on the corresponding states principle, and is a modification of the BWR equation of state.[14]

Physically based equations of state

There is a large number of physically based equations of state available today.[15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22] Most of those are formulated in the Helmholtz free energy as a function of temperature, density (and for mixtures additionally the composition). The Helmholtz energy is formulated as a sum of multiple terms modelling different types of molecular interaction or molecular structures, e.g. the formation of chains or dipolar interactions. Hence, physically based equations of state model the effect of molecular size, attraction and shape as well as hydrogen bonding and polar interactions of fluids. In general, physically based equations of state give more accurate results than traditional cubic equations of state, especially for systems containing liquids or solids. Most physically based equations of state are built on monomer term describing the Lennard-Jones fluid or the Mie fluid.

Perturbation theory-based models

Perturbation theory is frequently used for modelling dispersive interactions in an equation of state. There is a large number of perturbation theory based equations of state available today,[23][24] e.g. for the classical Lennard-Jones fluid.[11][25] The two most important theories used for these types of equations of state are the Barker-Henderson perturbation theory[26] and the Weeks–Chandler–Andersen perturbation theory.[27]

Statistical associating fluid theory (SAFT)

An important contribution for physically based equations of state is the statistical associating fluid theory (SAFT) that contributes the Helmholtz energy that describes the association (a.k.a. hydrogen bonding) in fluids, which can also be applied for modelling chain formation (in the limit of infinite association strength). The SAFT equation of state was developed using statistical mechanical methods (in particular the perturbation theory of Wertheim[28]) to describe the interactions between molecules in a system.[20][29][30] The idea of a SAFT equation of state was first proposed by Chapman et al. in 1988 and 1989.[20][29][30] Many different versions of the SAFT models have been proposed, but all use the same chain and association terms derived by Chapman et al.[29][31][32]

Multiparameter equations of state

Multiparameter equations of state are empirical equations of state that can be used to represent pure fluids with high accuracy. Multiparameter equations of state are empirical correlations of experimental data and are usually formulated in the Helmholtz free energy. The functional form of these models is in most parts not physically motivated. They can be usually applied in both liquid and gaseous states. Empirical multiparameter equations of state represent the Helmholtz energy of the fluid as the sum of ideal gas and residual terms. Both terms are explicit in temperature and density: with

The reduced density and reduced temperature are in most cases the critical values for the pure fluid. Because integration of the multiparameter equations of state is not required and thermodynamic properties can be determined using classical thermodynamic relations, there are few restrictions as to the functional form of the ideal or residual terms.[33][34] Typical multiparameter equations of state use upwards of 50 fluid specific parameters, but are able to represent the fluid's properties with high accuracy. Multiparameter equations of state are available currently for about 50 of the most common industrial fluids including refrigerants. The IAPWS95 reference equation of state for water is also a multiparameter equations of state.[35] Mixture models for multiparameter equations of state exist, as well. Yet, multiparameter equations of state applied to mixtures are known to exhibit artifacts at times.[36][37]

One example of such an equation of state is the form proposed by Span and Wagner.[33]

This is a somewhat simpler form that is intended to be used more in technical applications.[33] Equations of state that require a higher accuracy use a more complicated form with more terms.[35][34]

List of further equations of state

Stiffened equation of state

When considering water under very high pressures, in situations such as underwater nuclear explosions, sonic shock lithotripsy, and sonoluminescence, the stiffened equation of state[38] is often used:

where is the internal energy per unit mass, is an empirically determined constant typically taken to be about 6.1, and is another constant, representing the molecular attraction between water molecules. The magnitude of the correction is about 2 gigapascals (20,000 atmospheres).

The equation is stated in this form because the speed of sound in water is given by .

Thus water behaves as though it is an ideal gas that is already under about 20,000 atmospheres (2 GPa) pressure, and explains why water is commonly assumed to be incompressible: when the external pressure changes from 1 atmosphere to 2 atmospheres (100 kPa to 200 kPa), the water behaves as an ideal gas would when changing from 20,001 to 20,002 atmospheres (2000.1 MPa to 2000.2 MPa).

This equation mispredicts the specific heat capacity of water but few simple alternatives are available for severely nonisentropic processes such as strong shocks.

Morse oscillator equation of state

An equation of state of Morse oscillator has been derived,[39] and it has the following form:

Where is the first order virial parameter and it depends on the temperature, is the second order virial parameter of Morse oscillator and it depends on the parameters of Morse oscillator in addition to the absolute temperature. is the fractional volume of the system.

Ultrarelativistic equation of state

An ultrarelativistic fluid has equation of state where is the pressure, is the mass density, and is the speed of sound.

Ideal Bose equation of state

The equation of state for an ideal Bose gas is

where α is an exponent specific to the system (e.g. in the absence of a potential field, α = 3/2), z is exp(μ/kBT) where μ is the chemical potential, Li is the polylogarithm, ζ is the Riemann zeta function, and Tc is the critical temperature at which a Bose–Einstein condensate begins to form.

Jones–Wilkins–Lee equation of state for explosives (JWL equation)

The equation of state from Jones–Wilkins–Lee is used to describe the detonation products of explosives.

The ratio is defined by using , which is the density of the explosive (solid part) and , which is the density of the detonation products. The parameters , , , and are given by several references.[40] In addition, the initial density (solid part) , speed of detonation , Chapman–Jouguet pressure and the chemical energy per unit volume of the explosive are given in such references. These parameters are obtained by fitting the JWL-EOS to experimental results. Typical parameters for some explosives are listed in the table below.

| Material | (g/cm3) | (m/s) | (GPa) | (GPa) | (GPa) | (GPa) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNT | 1.630 | 6930 | 21.0 | 373.8 | 3.747 | 4.15 | 0.90 | 0.35 | 6.00 |

| Composition B | 1.717 | 7980 | 29.5 | 524.2 | 7.678 | 4.20 | 1.10 | 0.35 | 8.50 |

| PBX 9501[41] | 1.844 | 36.3 | 852.4 | 18.02 | 4.55 | 1.3 | 0.38 | 10.2 |

Others

See also

References

External links

Topics in continuum mechanics | |

|---|---|

| Divisions | |

| Laws and Definitions | |

| Solid and Structural mechanics | |

| Fluid mechanics | |

| Acoustics | |

| Rheology | |

| Scientists | |

| Awards | |

| State | ||

|---|---|---|

| Low energy | ||

| High energy | ||

| Other states | ||

| Transitions | ||

| Quantities | ||

| Concepts | ||

| Theory | ||

|---|---|---|

| Statistical thermodynamics | ||

| Models | ||

| Mathematical approaches | ||

| Critical phenomena | ||

| Entropy | ||

| Applications | ||

| 0.00      (0 votes) (0 votes) |

KSF

KSF